Abstract

Background:

Acute respiratory infection (ARI) in young children is responsible for an estimated 4.1 million deaths worldwide of which approximately 90% are due to pneumonia. To study the clinical effectiveness of co-trimoxazole versus amoxicillin in the treatment of non-severe pneumonia, as defined by WHO, in children in the age group of 02 months to 5 years. Randomized Control Trial study was conducted in out patient department of a large tertiary care hospital after taking consent from parents and ethical committee clearance.

Methods:

Children in study group were treated with amoxicillin (40 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) and those in control group were treated with co-trimoxazole (8 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim in 2 divided doses). All cases were reviewed on second and fifth day. The effectiveness and therapy failure were decided on the basis of clinical, radiological and complete blood count results.

Results:

Two hundred and four cases of non severe pneumonia were studied. All cases were diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria, as defined by WHO. Treatment failure was seen in 8.09% cases with amoxicillin and 39.05% cases with co-trimoxazole. Cost of one complete course with amoxicillin was 2.3 times higher than with co-trimoxazole. Compliance of therapy to co-trimoxazole (90.47%) was better than to amoxicillin (83.84%).

Conclusions:

The response to treatment with amoxicillin is faster, however, compliance is slightly poorer and cost of treatment high. In order to improve the compliance, better counseling and more studies are required to ascertain the efficacy of amoxicillin in higher dosage over a shorter period of time.

Keywords: Amoxicillin, acute respiratory infections, co-trimoxazole

INTRODUCTION

According to WHO estimates, in the year 1999, respiratory infections caused about 9, 87,000 deaths in India. Of which, 9, 69,000 were due to acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI), 10,000 due to acute upper respiratory infection (AURI) and about 9,000 due to otitis media. The burden of disease in terms of disability adjusted life years (DALY) lost was 25.5 million.[1] Overall incidence of acute respiratory infections (ARI) does not differ significantly between developed and developing countries, however there is strikingly high mortality in developing countries.[2] As the resistance to infection is not well developed in children below 5 years, they are more prone to develop pneumonia early and death may follow if treatment is not initiated in time.[3] There is strong evidence that bacteria cause a large proportion of child hood pneumonias in developing countries[4,5] with streptococcus pneumoniae and haemophilus influenzae as the leading bacterial cause of severe and fatal community acquired ARI.[5,6,7,8,9,10]

The department of child and adolescent health and development (CAH) of WHO, in collaboration with eleven other WHO programs and UNICEF, has developed the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) strategy to reduce mortality and morbidity from respiratory diseases.[5,11] WHO, IMCI recommends 5 days course of either oral co-trimoxazole or amoxicillin for the treatment of non-severe pneumonia. Both antibiotics are usually effective against streptococcal pneumonia and Haemophilus influenzae, are relatively in-expensive, widely available and are included in essential drugs list of the Ministry of Health.[5]

Co-trimoxazole is the drug used for treatment of pneumonia under ARI control program in India. Co-trimoxazole is less expensive with few side effects and can be used safely by health workers at the peripheral health facilities and at home by mothers.[4,12] However, studies in India have shown that resistance of streptococcus pneumoniae to co- trimoxazole is around 39-85%.[6] This necessitates thinking about an alternative antibiotic for the success of effective ARI control program in our country. Amoxicillin is the other drug recommended by WHO, in the treatment of non-severe pneumonia in ARI control program,[5] especially where the use of injectable antimicrobials is not feasible.[13,14] This study has been undertaken to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of co-trimoxazole versus amoxicillin in the treatment of non-severe pneumonia.

AIMS OF THE STUDY

To study the clinical effectiveness of co-trimoxazole versus Amoxicillin in the treatment of non-severe pneumonia, as defined by WHO, in children in the age group of 2 months to 5 years.

METHODS

All children in the age group of 2 months to 5 years, with WHO defined features of non-severe pneumonia, attending out patient department of a large tertiary care hospital were included in the study after taking written consent from parents. Institutional ethical committee clearance for the study was obtained. The cases were excluded if they have WHO signs of very severe pneumonia,[15] History of having received antibiotics for any illness anywhere 48 h before coming to the OPD. Previous history of wheezing including Asthma or children who have been prescribed corticosteroids along with bronchodilators, children with congenital heart disease, Immunodeficiency (congenital or acquired) including suspected or confirmed HIV infection, any chronic illness including chronic infections like tuberculosis, malignancy, acute/chronic organ disorder, known allergy/hypersensitivity to penicillin/Sulpha.

Patients were randomly assigned into study and control group by using standard randomization procedure. Children in study group were treated with amoxicillin (40 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses) and those in control group were treated with co-trimoxazole (8 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim in 2 divided doses).[3] X-ray chest and complete blood count (CbC) were done in all cases.

All cases were reviewed after 2 days and then 5 days after starting treatment.

The effectiveness and therapy failure were decided on the basis of clinical, radiological and complete blood count results. The clinical criteria alone were considered among X-ray negative and CBC negative cases. In X-ray positive and CBC positive cases, X-ray chest and CBC counts were repeated after complete course of treatment.

The clinical cure were defined as respiratory rate of less than 50 per min between 2 months to 1 year of age and less than 40 per min between 1 yr to 5 yr of age and absence of any of clinical signs of treatment failure given below.

Treatment failure was defined as follows.

Occurrence of any signs of WHO defined severe pneumonia[15]

Increase in respiratory rate more than 10 breaths per min above base line and

Respiratory rate more than 70 per min for children 2 months to 1 year of age or more than 60 per min for children between 1 year and 5 year of age.

Data thus obtained was tabulated, analyzed and subjected to statistical analysis, which was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 16.0.2) program for Windows and Statistical tests of significance (Chi-square) were applied and P values with significance of less than 5% were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In our study, 204 cases of non-severe pneumonia in children in the age group of 2 months-5 years were studied for clinical effectiveness of co-trimoxazole versus amoxicillin in their treatment. The following are the observations made from this study.

In our study 116 were boys and 88 girls. Male to female ratio was 1.32:1. The children were divided into 3 groups: 2months to 1 year, 1 year to 3 year and 3 year to 5 year. The maximum no of cases (40.20%) were in the age group of 1-3 years followed by 34.80% in the age group of 2 month-1 year and 25% in age group 3 year -5 years.

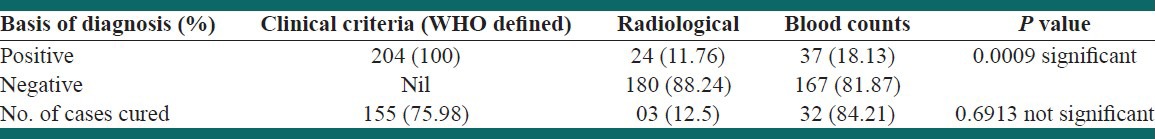

All cases were diagnosed on the basis of WHO defined clinical criteria; out of which only 1.76% cases showed radiological positivity while 18.13% showed raised blood counts which were statistically significant. Based on clinical criteria, 75.98% of cases showed good clinical response to either antibiotic [Table 1].

Table 1.

Basis of diagnosis and cure rate criteria

Complete blood count returned to normal after 5 days of treatment in 84.21% of positive complete blood count cases, which were done before starting treatment. Radiological cure rate was seen only in 12.5% of cases out of 24 positive cases. However, X-ray chest repeated after 14 days of treatment showed complete radiological cure in all radiologically positive cases.

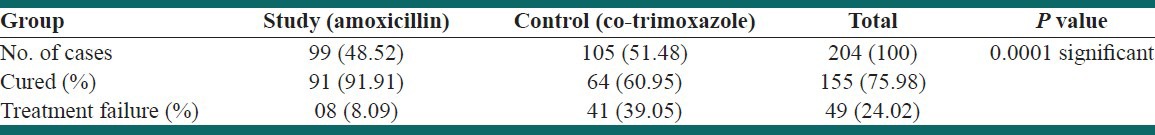

The distribution of cases among study and control group as per randomization is shown in Table 2. Treatment failure rate was 8.09% with amoxicillin and 39.05% with Co-trimoxazole which was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Treatment given and cure rate

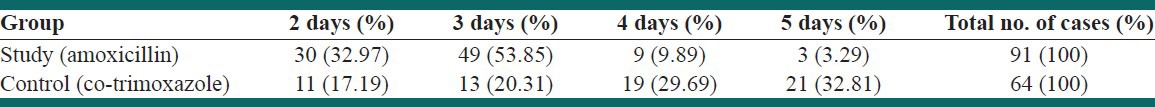

In study group, of all children with clinical cure, 86.82% children showed complete clinical response within 3 days of therapy with amoxicillin; whereas in control group 37.5% children showed complete clinical response within 3 days of co-trimoxazole which was not statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mean period of response

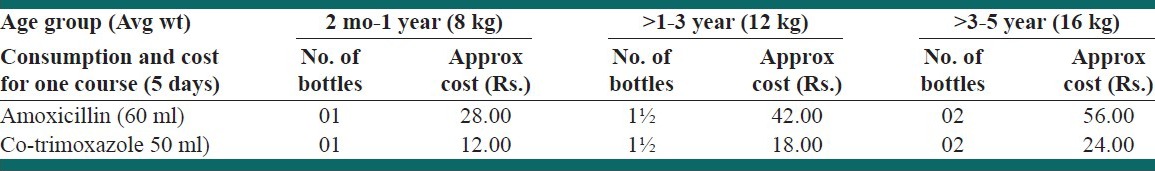

Bottle to bottle consumption in both groups was almost the same. Approximate cost of treatment for one course in amoxicillin group is Rs. 28.00 (2 months-1 year), Rs 42.00 (1-3 years) and Rs. 56.00 (3-5 years). In comparison, approximate cost of co-trimoxazole was Rs 12.00 (2 months-1 year age group), Rs 18.00 (1-3 years) and Rs. 24.00 (3-5 years age group). In general, the cost of treatment with amoxicillin was 2.3 times the cost of co-trimoxazole [Table 4].

Table 4.

Total consumption and cost of one course of treatment

(Patients were interviewed after the course of treatment and asked about no. of doses missed.)

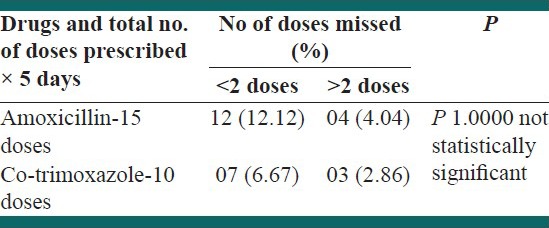

Compliance was measured on the basis of no. of doses missed in each group; 12.12% cases missed less than 2 doses and 4.09% missed more than 2 doses. In control group 6.67% cases had missed less than 2 doses and 2.86% more than 2 doses [Table 5].

Table 5.

Compliance factor

DISCUSSION

Infections of the respiratory tract are perhaps the most common human ailment leading to significant morbidity and mortality in young children. ARI are a major economic burden on families and the health care system. One in three hospital admissions of children in developing countries is due to pneumonia. Treatment of ARI also often involves the unnecessary or inappropriate use of antibiotics and other drug in outpatient services.

Clinical features of pneumonia vary; onset is abrupt with headache, chills, cough and high fever. No single clinical sign has a better combination of sensitivity and specificity to detect pneumonia in children under 5 years, than respiratory rate, specifically fast breathing.[5] The WHO ARI program was officially established at global level in 1982 and the shifted its emphasis from biomedical research to operational and program implementation.[4] On the basis of research and experience in Papua New Guinea and other countries, a standard method for case management has been developed to enable primary health workers to: (a) recognize important signs and symptoms such as fast breathing and chest in-drawing: (b) determine the nature of cases, whether mild, moderate or severe; and (c) decide whether antibiotics should be given and whether patients should be referred to hospitals. The same information has been given to mothers through health education.[4] Since the development of WHO's standard case management guidelines, the program has concentrated on the establishment and expansion of national control programs. According to USAID health reports, in Nepal, standard ARI case management has contributed to a 42% decline in less than 5 mortality.[16]

In India, the acute respiratory disease control program was taken up as a pilot project in year 1990. Since 1992-93 the program is being implemented as part of child survival and safe motherhood (CSSM) program.[12] In 1996, the WHO control of diarrheal disease (CDD) and ARI program were merged in the Regional Office. This was mainly because both programs were targeted at children under 5 years of age; integrating them made both program more effective.[4] Training of health workers in case management with an emphasis on hands-on practice and improving the communication skills of health workers has remained the priority activity for most of the national programs.[4] The measurement of program impact in terms of ARI death reduction in children under 5 years of age remains beyond the reach of most national programs. However, some surveys carried out on limited scale have shown encouraging results.[14]

A.K. Patwari et al. in their study found that ARI constituted 26.88% of hospital admissions during 2 years study period. Ninty four percent of all admissions due to ARI were below the age of 5 years.[2]

Our study was carried out in children attending out patients department of large tertiary care service hospital with an aim of finding out the clinical effectiveness of co-trimoxazole versus amoxicillin for WHO defined non-severe pneumonia by a randomized controlled trial.

During the period of study, 204 patients with WHO criteria of non-severe pneumonia were included in the study. Out of total 204 cases almost 75% of the cases were below the age of 3 years. This is in concordance with other studies that have shown maximum no. of cases in the age group below 3 years.[14,17,18,19,20,21]

Male preponderance was noticed in our study with M:F ratio being 1.32:1. This is similar to the findings of others studies.[14,17,18,21] Higher incidence among males may be due to their increase exposure to outdoor activities and a bias towards male sex.

All cases were included in the study on the basis of WHO defined clinical criteria for diagnosis of non severe pneumonia.[15] However in all cases X-ray chest and complete blood counts (Hb, TLC, and DLC) were carried out before the treatment and in positive cases these were repeated after treatment. 11.76% cases showed X-ray findings suggestive of pneumonia. This percentage of radiological positivity in case of pneumonia in our study is similar to the study by Lucas et al. (13.79%)[18] and Qazi et al. (14%).[21] Blood counts were positive in 18.13% cases. MN Lucas has shown similar% age of positivity in his study.[18]

In our study almost 81.7% of the cases were diagnosed as non severe pneumonia on clinical grounds only. Radiological and hematological investigations were helpful in only small percentage of cases. As tachypnea is the earliest sign of pneumonia before the radiological and laboratory evidence of pneumonia occur, clinical criteria on the basis of respiratory rate, is the best method with combination of high sensitivity and specificity to detect pneumonia in children below 5 years of age.[5]

Out of total 204 cases, study group included 99 (48.52%) cases and control group included 105 (51.48%) cases. Study group was treated with amoxicillin and control group was treated with co-trimoxazole in doses as mentioned in material and methods. The cure rate among children of study group (amoxicillin) was 91.91% cases and in control group (co-trimoxazole) 60.95%. Higher cure rate with amoxicillin in our study is similar to the reports of other workers who have reported cure rates varying from 70.9-93%.[7,13,20,22,23]

Ostroff et al. in their study found resistance to co-trimoxazole to be higher as compared to ampicillin for bothy S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae. Susceptibility of S. pneumonia to penicillin was 70.9 to 77.6% and co trimoxazole was 73-75% and susceptibility of H. influenzae to ampicillin was 93-100% and to co-trimoxazole was 84.9% to 100%.[20]

Relatively higher cure rate with amoxicillin in our study could be because of number of factors like availability of medicines free of cost and in sufficient quantity, educated clientele resulting in early reporting to the hospital and regular counseling regarding nature of disease and importance of compliance.

Cure rate among co-trimoxazole group in our study was 60.95%. Other studies have reported figures from 22.2 to 81%.[7,13,20,22,23,24] It will be seen from the results of various studies that over a period of time the cure rate is showing a gradual decline indicating that resistance to co-trimoxazole is increasing. International clinical epidemiology network (INCLEN), invasive bacterial infection surveillance (IBIS) group, in their study “prospective multi center hospital surveillance of “streptococcus pneumonia disease in India” found resistance of S. pneumonia to co-trimoxazole to be around 78%, 85%, 73% and 39% of 217 isolates of S. pneumoniae from Delhi, Madras, Nagpur and Vellore respectively. Since this data was from six centers in different regions collected over 4 years, it is likely to be representative of data from most of the country.[6]

About 86% of children in amoxicillin group showed clinical cure by third day. Corresponding figure for the co-trimoxazole group was 37%. Compliance of treatment improves significantly when the total duration of therapy is reduced. Shally Awasthy has found good response to amoxicillin after 2 days of treatment.[14] Shamim Quazi et al. in their study of clinical efficacy of 3 days versus 5 days of oral amoxicillin for treatment of childhood pneumonia found that in children with non-severe pneumonia, treatment for three days (79%) was as effective as treatment for 5 days (80%). The most important risk factor for treatment failure was non-compliance, which was also associated with longer duration of therapy. They opined that shorter antibiotic course could help to contain the spread of antimicrobial resistance.[21]

De Francisco and Chakraborty found good response with 3 days of co-trimoxazole which is contrary to our study. Since this study was done 9 years back and resistance to co-trimoxazole has increased over a period of time, mean period of response to co-trimoxazole appears to have increased too.[24] Further studies are required to find out whether increasing the dose of amoxicillin and cutting down the total duration of therapy to 3 days will achieve cure in 100% cases.

Total no. of doses to be taken for a full course and cost of one complete course of treatment in each group is different. 15 doses of amoxicillin and 10 doses of co-trimoxazole are required to be taken to complete the course of each drug for 5 days. Cost of amoxicillin for a complete course is approximately 2.3 times higher than co-trimoxazole. Irrespective of the efficacy, this difference in the cost could be an important factor while recommending the standard drug for use in community setting.

Compliance factor was determined by interviewing children/parents after the complete course of treatment (i.e., 5 days) by inquiring about the no. of doses missed. Compliance among both groups was good. However comparatively, compliance was relatively poorer in amoxicillin group (appro × 84%) compared to co-trimoxazole (90%). Better compliance in co-trimoxazole group is probably related to lesser no of daily doses to be administered to the patient.

De Francisco in his study with co-trimoxazole found that around 25% cases missed more than 2 doses, giving a compliance factor of 75%.[24] Keeley on the other hand found 100% compliance and attributed it to good counseling of parents.[25] S. Qazi found high compliance to both drugs with non compliance rate of 3.9% (amoxicillin) to 3.4% (in co-trimoxazole) group. Higher percentage of compliance in our study can be attributed to better counseling and relatively better educated clientele in service set up.[21]

S.A. Quazi et al. in their study over 4 years in Pakistan found that with standard management of ARI as per WHO recommendation in children, the total no. of patients decreased by 26.2% over 4 years, while the under 5 years old ARI patients decreased by nearly 32.7%. The case fatality rate in children admitted with ARI fell from 9.9 to 4.9% similar results were reported from Napoleon.[26]

CONCLUSIONS

Children under the age of 3 years are more susceptible to get non severe pneumonia. Clinical criteria as defined by WHO remains the best method to diagnose non severe pneumonia. Amoxicillin is coming up as a fairly good substitute for co-trimoxazole which is showing increasing resistance to most bacteria. The response to treatment with amoxicillin is faster, however, compliance is slightly poorer and cost of treatment high. In order to improve the compliance, better counseling and more studies are required to ascertain the efficacy of amoxicillin in higher dosage over a shorter period of time. Although in various studies including the present one, amoxicillin has come out to be better drug in the treatment of non severe pneumonia, it can not be recommended as the first line drug in community practice because of significantly higher cost especially in poor country like India. Region wise studies on the pattern of current studies need to be carried out to find areas where there is significant resistance to co-trimoxazole.

Footnotes

Source of Support: ICMR SRF Project

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.The world health reports 1999. Making a difference, Report of the director General WHO. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/1999/en/whr99_en.pdf .

- 2.Patwari AK, Aneja S, MandaI RN, Mullick DN. Acute respiratory infections in children: A hospital based report. Indian Pediatr. 1988;25:613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandora TJ, Sectish TC. Community acquired pneumonia. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012. pp. 1474–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fifty Years of the World Health Organization in the Western Pacific Region, 1948-1998: Report of the Regional Director to the Regional Committee for the Western Pacific. Forty-ninth session. Acute respiratory infections. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/about/in_brief/RC49_03.pdf .

- 5.WHO. Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development (CAH), Handbook, Integrated Management of Childhood illness (imci) 2003. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241546441.pdf .

- 6.Prospective multicentre hospital surveillance of streptococcus pneumoniae disease in India. Invasive Bacterial Infection Surveillance (IBIS) Group, International Clinical Epidemiology Network (inclen) Lancet. 1999;353:1216–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastro TD, Nomani NK, Ishaq Z, Ghafoor A, Shaukat NF, Esko E, et al. Use of nasopharyngeal isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae from children in Pakistan for surveillance for antimicrobial resistance. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:824–30. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escobar JA, Dover AS, Dueñas A, Leal E, Medina P, Arguello A, et al. Etiology of respiratory tract infections in children in Cali, Colombia. Pediatrics. 1976;57:123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman M, Stratton D, Diallo A, Egler LJ. Diagnosis of acute bacterial pneumonia in Nigerian children. Value of needle aspiration of lung of countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis. Arch Dis Child. 1977;52:925–31. doi: 10.1136/adc.52.12.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shann F, Gratten M, Germer S, Linnemann V, Hazlett D, Payne R. Etiology of pneumonia in children in Goroka hospital, Papua New Guinea. Lancet. 1984;2:537–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Management of childhood illness in developing countries, rationale for an integrated strategy: imci: Information. WHO. 1999. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 17]. pp. 3–4. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/chs_cah_98_1a/en/index.html .

- 12.Park K. 16th ed. Jabalpur: Banarasidas Bhanot and Company; 2006. Park's textbook of preventive and social medicine; p. 521. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straus WL, Qazi SA, Kundi Z, Nomani NK, Schwartz B. Antimicrobial resistance and clinical effectiveness of cotrimoxazole versus amoxycillin for pneumonia among children in Pakistan: Randomized controlled trial. Pakistan Co-trimoxazole Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352:270–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)10294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Awasthi S. Clinical response to two days of oral amoxycillin in children with non-severe pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Report of consultative Meeting to Review Evidence and Research Priorities in the Management of Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Agency for International development (usaid), maternal and child health, technical areas, acute respiratory infections. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.transition.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/mch/ch/techareas/aribrief.html .

- 17.Murphy TF, Henderson FW, Clyde WA, Jr, Collier AM, Denny FW. Pneumonia: An eleven-year study in a pediatric practice. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113:12–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas MN, Liyanage UA, Loku Kankanamage L. A study of antibiotic usage in acute respiratory infections in children. Sri Lanka J Child Health. 2001;30:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker J, Gratten M, Riley I, Lehmann D, Montgomery J, Kajoi M, et al. Pneumonia in children in the eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea: A bacteriologic study of patients selected by standard clinical criteria. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:348–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostroff SM, Harrison LH, Khallaf N, Assaad MT, Guirguis NI, Harrington S, et al. The Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Study Group. Resistance patterns of streptococcus pneumoniae and haemophilus influenzae isolates recovered in Egypt from children with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1069–74. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pakistan Multicentre Amoxycillin Short Course Therapy (MASCOT) pneumonia study group. Clinical efficacy of 3 days versus 5 days of oral amoxicillin for treatment of childhood pneumonia: A multicentre double-blind trial. Lancet. 2002;360:835–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotrimoxazole Amoxicillin Trial in Children Under 5 Years For Pneumonia (CATCHUP Study Group) Clinical efficacy of cotrimoxazole versus amoxicillin twice daily for treatment of pneumonia: A randomized controlled clinical trial in Pakistan. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:113–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance among nasopharyngeal isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae– Bangui, Central African Republic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;46:62–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Francisco A, Chakraborty J. Adherence to cotrimoxazole treatment for acute lower respiratory tract infections in rural Bangladeshi children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1998;18:17–21. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1998.11747920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeley DJ, Nkrumah FK, Kapuyanyika C. Randomized trial of sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim versus procaine penicillin for the outpatient treatment of childhood pneumonia in Zimbabwe. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:185–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qazi SA, Rehman GN, Khan MA. Standard management of acute respiratory infections in a children's hospital in Pakistan: Impact on antibiotic use and case fatality. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:501–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]