Abstract

Cervical cancer is a common gynecological malignancy and a frequent cause of death. Patient outcome depends on tumor stage, size, nodal status, and histological grade. Correct tumor staging is important to decide the the treatment strategy. Magnetic Resonance Imaging is accepted as a preferred imaging modality to assess the prognostic factors.

Keywords: Carcinoma, cervix, MRI, staging

Introduction

Uterine cervical cancer is the third most common malignancy affecting the female genital tract in middle age group between 45 and 55 years.[1,2] Its incidence is increasing rapidly in developing countries. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system updated in 2009 [Table 1] is commonly used for treatment planning but is inadequate in the evaluation of prognostic factors like tumor volume and nodal status.[1,3] Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality because of its ability to assess soft tissue in detail, permitting thereby better identification of stromal and parametrial invasion as compared to computed tomography (CT). Radiation exposure and inaccuracies in detection of parametrial invasion are the other limitations of CT. MRI tells us the exact volume, shape, and direction of the primary lesion, local extent of the disease, and nodal status accurately, which helps the clinician in treatment planning. Tumor behavior to chemoradiation is also better evaluated with MRI. FIGO staging system is used to stage cervical cancer on MRI.[4] Histologically, squamous cell carcinoma is the commonest type. Other types are adenocarcinoma, adenoid-cystic, adenoid-basal, and small cell carcinoma.[5]

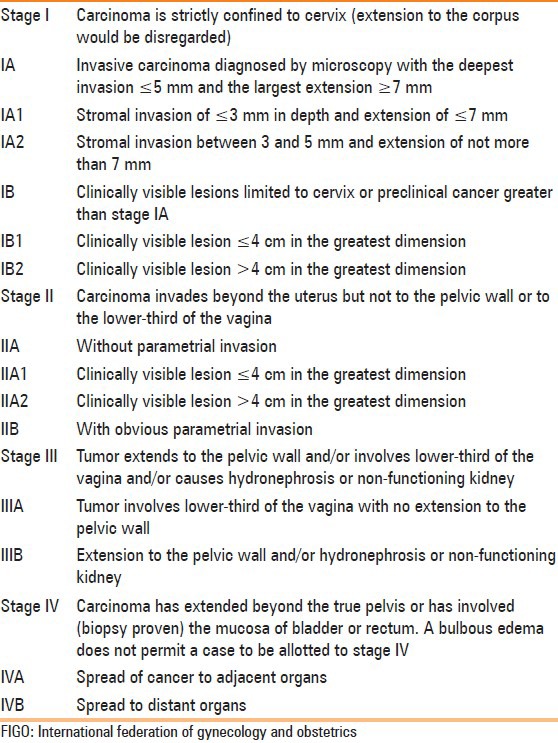

Table 1.

FIGO staging for carcinoma of cervix

MRI protocol

MRI was performed on GE Signa HDxt 1.5 Tesla unit, USA. Patient is instructed to fast for 4 h before examination to reduce small bowel peristalsis artifacts. Axial T1W images are obtained from the kidney to perineum using 256 × 256 matrix, 32 cm field of view (FOV), 4 mm slice thickness, 1 mm interslice gap, and 2 number of excitation (NEX). This is optimal for evaluation of the pelvis and lower abdomen for lymphadenopathy and hydronephrosis. High-resolution T2W images of pelvis are acquired in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes using 512 × 256 matrix, 24 cm FOV, 4 mm slice thickness, 1 mm interslice gap, and 2 NEX for the evaluation of primary tumor spread. It allows the evaluation of tumor extension to the body of uterus, vagina, parametrium, rectal wall, and urinary bladder wall. Oblique axial T2W images planned perpendicular to the long axis of cervix give more accurate assessment of stromal involvement and parametrial invasion. Fat-suppressed sequences can be useful for the evaluation of parametrial involvement. Post-contrast images are obtained in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes, and are useful to identify bladder and rectal wall invasion, fistulas, and in the detection of recurrent tumor. Routine post-contrast images can overestimate stromal and parametrial invasion.[6] Dynamic images obtained 30-60 seconds after gadolinium injection are helpful for the assessment of smaller tumors which are not visible on T2W images as they show increased early contrast enhancement relative to the cervical stroma.[7]

Normal cervix

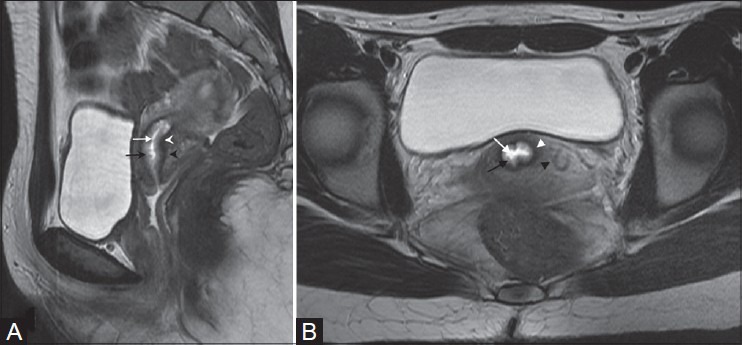

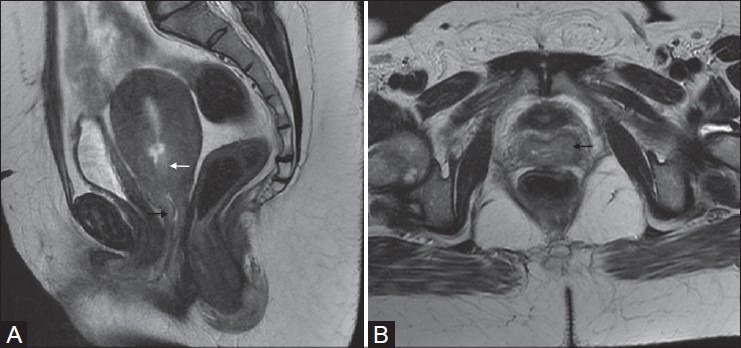

The cervix is divided into supravaginal and vaginal portions by fornices; the supravaginal portion is lined by columnar cells and the vaginal portion by squamous cells.[4,6] MRI anatomy of the cervix is best delineated on T2W image [Figure 1] as it outlines the four major zones of cervix. From center to periphery, these are high signal intensity endocervical canal, intermediate signal intensity plicae palmatae, low signal intensity fibrous stroma, and intermediate signal intensity outer smooth muscle.[4]

Figure 1.

Normal cervix. The four major zones are very well depicted on T2W images. High signal intensity endocervical canal, intermediate signal intensity plicae palmatae, low signal intensity fibrous stroma, and intermediate signal intensity outer smooth muscle are indicated by white arrow, black arrow, white arrow-head, and black arrow-head, respectively

MRI findings

Mortality with invasive cervical cancer is unexpectedly high and is around 30%. These patients expire from recurrent or persistent disease.[8] Hence, early detection of the disease, its correct staging, and treatment are of great importance. Tumors generally originate from the squamocolumnar junction, and this is why, exophytic masses are common in younger females whereas endocervical masses are common in older females.[1] T2W images play a crucial role in identification of the primary tumor and assessment of its extent.[9] Acquisition in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes is sufficient for staging in most of the cases. These masses show intermediate to high signal on T2W images. Early tumor can be identified on dynamic contrast-enhanced images.[10] Diffusion-weighted images have some role in making the diagnosis. Tumor tissue has significantly low apparent diffusion coefficient value as compared to nontumor tissue.[9]

Tumor Spread

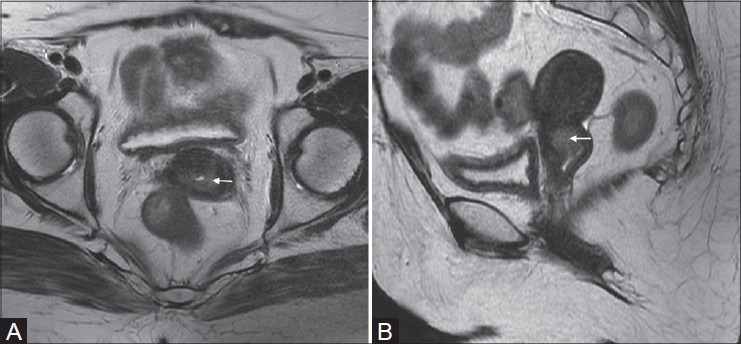

Stage I tumor is limited to cervix. Stage IA is microscopic disease and is not visible on MRI. A visible tumor clinically stage the patient as IB or higher [Figures 2 and 3]. Peripheral T2-hypointense stroma is maintained in IB.[1,4]

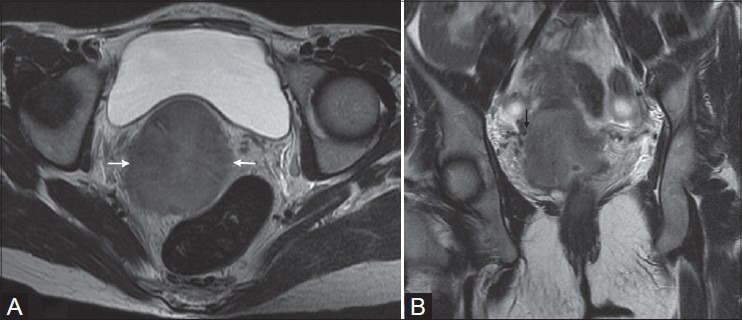

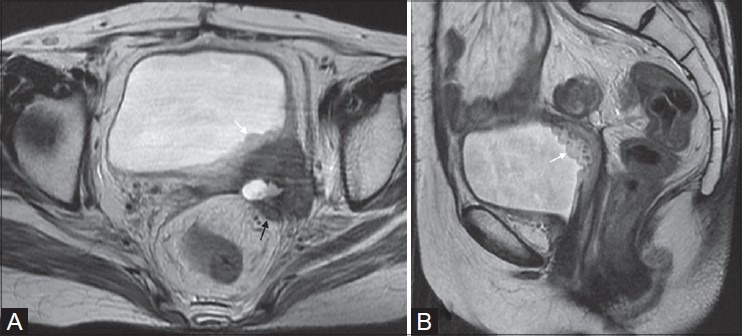

Figure 2(A, B):

A 50-year-old female with squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (stage IB1). Axial and sagittal T2W images reveal hyperintense mass confined to cervix (white arrows in A and B)

Figure 3(A, B):

A 39-year-old female with carcinoma cervix (stage IB2). Polypoidal cervical mass is seen extending in endometrial cavity (black arrow in B). Preserved peripheral hypointense stromal ring (white arrow in A) is well seen on T2W sequence

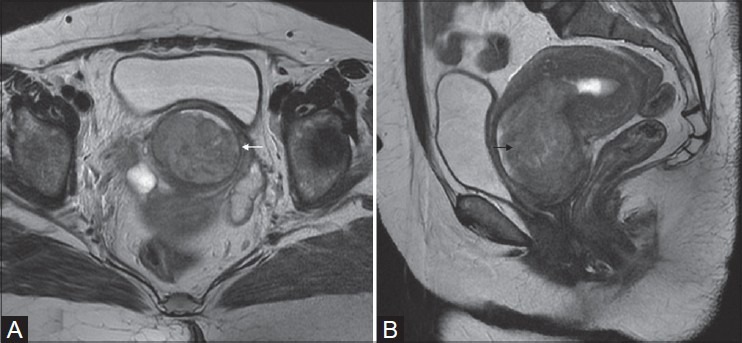

Stage II is considered when the tumor extends beyond the cervix. Involvement of the upper two-third of the vagina is seen as segmental loss of the normally seen T2-hypointense vaginal wall and is staged as IIA [Figure 4]. According to revised FIGO staging, if the tumor size is ≤4 cm, it is stage IIA1 and if it is >4 cm, it is stage IIA2. In stage IIB, the tumor disrupts the normally seen hypointense peripheral stroma on T2W images and extends in the parametrium [Figure 5].[1,4] Intact T2-hypointense stroma ring has a high negative predictive value for parametrial invasion and is between 94% and 100%.[6] Confident diagnosis of parametrial invasion is made when one sees the spiculated tumor-parametrial interface, soft tissue mass in parametrium, encasement of periuterine vessels, and ureter.[11,12,13] MRI sometimes can overstage large tumors due to edema or inflammation caused by tumor compression, which should be kept in mind while planning treatment.[11]

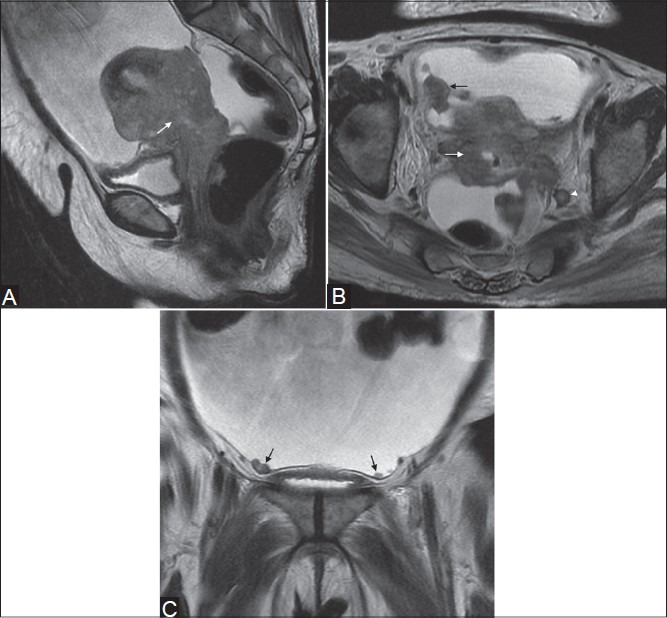

Figure 4(A, B):

A 49-year-old female with adenocarcinoma of uterine cervix (stage IIA). Sagittal and axial T2W images show ill-defined hyperintense mass in the cervix (white arrow in A) and extending into upper third of the vagina along the the anterior and posterior walls (black arrows in A and B)

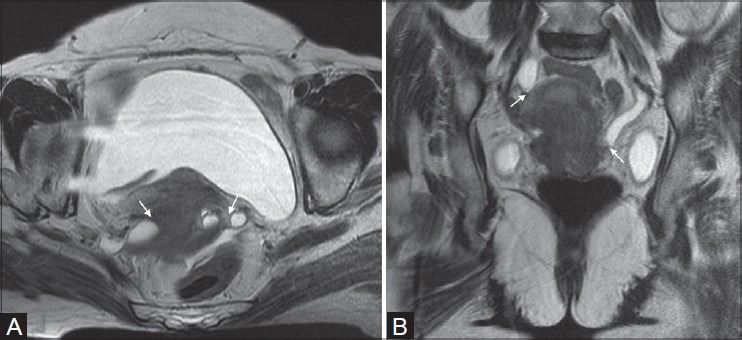

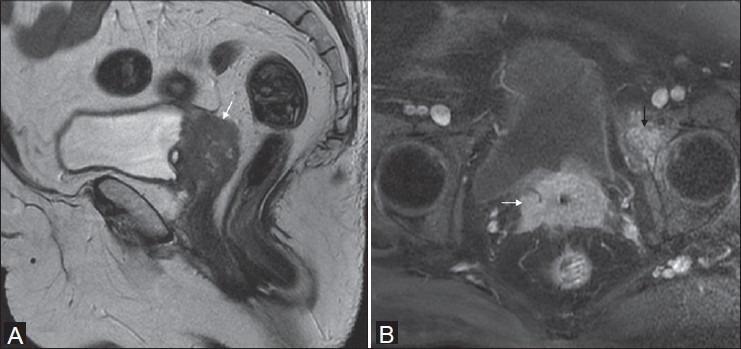

Figure 5(A, B):

Squamous cell carcinoma in a 40-year-old female (stage IIB). Mass in cervix causing disruption of outer T2-hypointense stromal ring (white arrow in A) with extension into parametrium and abutting the parametrial vessels (black arrow in B)

Stage III is defined as tumor extension to the lower third of the vagina or lateral pelvic wall with associated hydronephrosis. Involvement of lower third of the vagina without extension to pelvic wall is IIIA [Figure 6]. Rarely, one may see the infiltration of posterior bladder wall without extension to the bladder mucosa. Stage IIIB is considered when the tumor is less than 3 mm from the side wall, causes hydroureter, infiltrates the obturator internus, pyriformis, and levator ani muscles, encases the iliac vessels, and destroys the pelvic bones [Figure 7].[10,12]

Figure 6.

A 65-year-old female with poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (stage III A). Hyperintense mass infiltrating the vaginal fornices and extending caudally to lower third of the vagina along the the anterior and posterior vaginal walls (white arrow). Collection in endometrial cavity is seen as hyperintensity (black arrow)

Figure 7(A, B):

Cancer of uterine cervix in a 65-year-old female (stage IIIB). Axial and coronal T2W images show intermediate signal intensity cervical tumor with parametrial invasion and involvement of distal ureters bilaterally (white arrows in A and B)

Presence of bladder or rectal mucosa involvement or distant metastasis upgrades the tumor to stage IV. In stage IVA, bladder and rectal invasion is suggested by the presence of focal or diffuse disruption of the normally seen T2-low signal intensity wall, irregular or nodular wall, and presence of an intraluminal mass [Figure 8]. Bulbous edema sign, which is hyperintense thickening of the bladder mucosa on T2W images, is an indirect sign of invasion and should be evaluated with care for associated tumor nodule [Figure 9].[1,11] Accuracy of MRI for bladder and rectal wall invasion increases with contrast-enhanced images as compared to T2W images.[7] Distant spread of tumor to the liver, lung, bones, peritoneum, and soft tissue is defined as stage IVB [Figure 10]. Rarely, adrenals, spleen, kidneys, pancreas, and gastrointestinal tract are involved.[14]

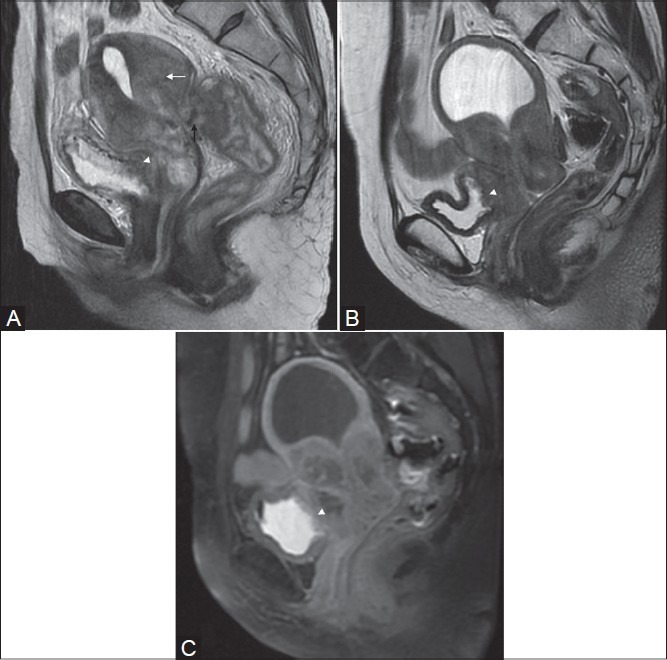

Figure 8(A-C):

Squamous cell carcinoma in two different patients (stage IVA). Sagittal T2W image shows a large mass arising from the cervix and involving the uterine myometrium (white arrow in A) with invasion in the rectum demonstrated as loss of T2-low signal intensity rectal wall (black arrow in A). Also note the infiltration in posterior bladder wall (white arrow-head in A), better seen in the second patient on T2 and post-gadolinium image (white arrow heads in B and C)

Figure 9(A, B).

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in a 54-year-old lady. Recurrent mass infiltrating left posterolateral bladder wall with hyperintense thickening of the bladder mucosa on T2W images, typically called bulbous edema sign (white arrows in A and B). Note the infiltration of mesorectal fascia and extension in the mesorectum (black arrow in A)

Figure 10(A-C).

A 54-year-old female with squamous cell carcinoma (stage IVB). Sagittal (A), axial (B), and coronal (C) T2W images reveal cervical mass infiltrating the corpus and upper vagina and adherent to the bladder and rectal wall (white arrows in A and B). Nodular peritoneal deposits are demonstrated on axial and coronal images (black arrows in B and C). Note the enlarged lymph node along left internal iliac vessels (white arrow-head in B)

Lymph Node Involvement

Lymph node metastasis initially occurs to pelvic nodes, which then subsequently spreads to retroperitoneal and supraclavicular nodes. Paracervical and parametrial nodes are first to be involved, followed by spread to external iliac nodes by lateral route, internal iliac nodes by hypogastric route, and lateral sacral and sacral promontory nodes by presacral route.[6,13] Although pelvic lymph node metastasis is not considered in FIGO staging, it is one of the important prognostic factors and presence of a positive node indicates poor prognosis in each stage. Presence of metastatic para-aortic or inguinal node is classified as stage IVB disease. Identification of diseased node on imaging is based on size and morphology. A lymph node having transverse diameter >10 mm is abnormal. Morphological criteria that indicate pathological lymph node are border irregularity, heterogeneity of signal on T2W images, and presence of necrosis [Figure 10B].[15]

Impact on Treatment and Therapeutic Options

Error rates in clinical examination are significantly high, hence clinical staging may not be accurate in each and every patient.[6] Important parameters that the clinicians want to know are accurate size of the tumor, status of parametrium, pelvic side walls, presence of lymph nodes, and spread to local and distant organs [Table 2]. MRI answers all these questions. Identification of early disease from advanced disease is crucial for treatment planning.[11] Standard treatment for stage IA1 is cervical conization or total hysterectomy. In total hysterectomy, removal of uterus, cervix, adjacent tissue, and small cuff of the upper vagina in a plane outside the pubocervical fascia is performed. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is generally not advisable because the risk of pelvic lymph node metastasis is less than 1%. In stage IA2, modified radical hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection is recommended because the risk of pelvic lymph node metastasis increases to 5%. In modified radical hysterectomy, uterus, cervix, 1-2 cm of upper vagina, paracervical tissue, and medial half of cardinal ligament and uterosacral ligament are removed.[16] Stages IB and IIA are treated either with combined external beam radiation and brachytherapy (BT) or radial hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection. Effectiveness of both these treatments is equal, and the survival rate in both varies between 80% and 90%. Concurrent chemotherapy with cisplatin has been shown to improve the patient survival. External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) delivers homogeneous dose to the primary tumor in cervix, local tumor extension in parametrium, uterosacral ligaments, and vagina, draining regional lymph nodes, and known areas of lymph node involvement. It improves the efficacy of subsequent BT by shrinking the tumor. EBRT dose to the planning treatment volume is between 45 and 50.4 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions. BT is a critical component of radiotherapy (RT) and is generally performed using an intracavitary approach. High dose delivery of 80 Gy or more to the target area is possible with BT, which cannot be delivered with EBRT alone. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is useful when high dose is required to treat the disease in regional lymph nodes. It decreases the dose to bowel, bladder, and bone marrow. It also reduces the gastrointestinal and hematologic toxicity.[17] Radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard treatment for stage IIB, III, and IVA tumors. Patients without nodal disease or with disease limited to the pelvis are treated with pelvic RT, concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and BT. Patients with positive para-aortic and pelvic nodes are treated with extraperitoneal lymph node dissection followed by extended field RT, concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and BT. Stage IVB patients are incurable and cisplatin-based chemotherapy is the primary treatment offered to these patients. Localized RT can provide effective relief from pain caused by metastasis to distant organs. Recurrent disease limited to pelvis after radical hysterectomy is treated with aggressive RT. Recurrent disease after definitive irradiation is generally treated with anterior pelvic exenteration. In pelvic exenteration, urinary bladder, rectum, vagina, ovaries, fallopian tube, and all other supporting tissue in the pelvis are removed. A urinary conduit, a transverse or sigmoid colostomy, and a neovagina are created.[16]

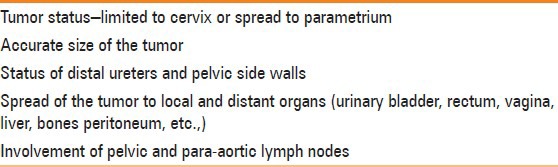

Table 2.

Essential elements to be included in the report

Post-treatment Appearance

After surgery, one can observe the normal lower two-third of the vagina, seen as low signal intensity muscular wall on T2W images. Sometimes, a fibrotic scar is present. Post-radiation, the cervix loses its normal zonal anatomy and exhibits homogeneously low signal intensity stroma on T2W images which is a reliable indicator of tumor-free cervix [Figure 11].[14]

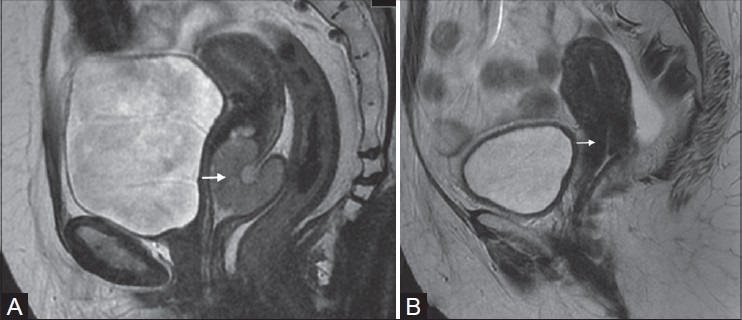

Figure 11(A, B).

Hyperintense mass in the cervix and upper vagina on pre-treatment. T2W sagittal image (white arrow in A) in a 42-year-old female. Homogeneous T2-hypontense stroma in the same patient treated with radiotherapy (white arrow in B)

Recurrent Tumor

Tumor recurrence is defined as development of new local tumor or metastasis at least 6 months after the treated lesion has regressed [Figure 12]. Tumor stage, size, histological findings, depth of stromal invasion, and nodal status at initial presentation are the risk factors for recurrence.[13,14] It usually occurs in the pelvis at vaginal cuff, cervix, parametrium, pelvic lateral walls, bladder, and rectum within 2 years of completion of the primary treatment. Tumor can also recur in local or distant lymph nodes and in at-risk organs for metastasis. Challenge to the radiologist is to differentiate between post-radiation changes and recurrent tumor. MRI has high sensitivity but low specificity for recurrent disease. Dynamic contrast imaging increases the accuracy by identifying the early enhancing, intermediate to high T2-signal intensity recurrent mass lesion.[6] A fibrotic scar appears as low signal intensity on T2W images.

Figure 12(A, B).

Operated case of Ca cervix in a 71-year-old female. Sagittal T2W image (A) shows intermediate signal intensity recurrent mass at vaginal vault (white arrow). Oblique axial T1 fat-suppressed post-gadolinium image (B) shows homogeneous enhancement of the mass (white arrow) with secondary deposit in the anterior column of left acetabulum (black arrow)

Conclusion

MRI is very useful in local staging of the disease. It is a valuable tool in assessing the spread of the tumor to local and distant lymph nodes. It also assesses the disease response to chemoradiation and differentiates residual or recurrent disease from radiation fibrosis. Thus, MRI is valuable in deciding the treatment strategies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Nicolate V, Carignan L, Bourdon F, Prosmanne O. MR imaging of cervical carcinoma: A practical staging approach. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1539–49. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.6.g00nv111539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szklaruk F, Tamm E, Choi H, Varavithya V. MR Imaging of common and uncommon pelvic masses. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:403–24. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FIGO Committ ee on Gynecologic Oncology. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;105:103–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto Y, Tanaka YO, Nishida M, Tsunoda H, Yoshikawa H, Itai Y. MR Imaging of the uterine cervix: Imaging-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:425–45. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lax S. Histopathology of cervical precursor lesions and cancers. Acta Dermatoven APA. 2011;20:125–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur H, Silverman PM, Iyer RB, Verschraegen CF, Eifel PJ, Charnsangavej C. Diagnosis, staging and surveillance of cervical carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1621–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinkel K, Brown M, Sirlin C. Malignant disorders of the female pelvis. In: Edelman RR, Hesselink JR, Zlatkin MB, Crues JV, editors. Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2005. pp. 5580–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engin G, Kucucuk S, Olmez H, Hasiloglu ZI, Disci R, Aslay I. Correlation of clinical and MRI staging in cervical carcinoma treated with radiation therapy: A single cancer experience. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2011;17:44–51. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.3114-09.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charles-Edwards EM, Messiou C, Morgan V, De Silva SS, McWhinney NA, Katesmark M, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in cervical cancer with an endovaginal technique: Potential value for improving tumor detection in stage Ia and Ib1 disease. Radiology. 2008;249:541–50. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Follen M, Levenback CF, Iyer RB, Grigsby PW, Boss EA, Delpassand ES, et al. Imaging in cervical cancer. Cancer Suppl Suppl. 2003;98:2028–38. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sala E, Wakely S, Senior E, Lomas D. MRI of malignant neoplasm of the uterine corpus and cervix. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1577–87. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pannu HK, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT evaluation of cervical cancer: Spectrum of disease. RadioGraphics. 2001;21:1155–68. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.5.g01se311155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Son H, Kositwattanarerk A, Hayes MP, Chuang L, Rahaman F, Heiba S, et al. PET/CT evaluation of cervical cancer: Spectrum of disease. Radio Graphics. 2010;30:1251–68. doi: 10.1148/rg.305105703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feong YY, Kang HK, Chung TW, Seo FF, Park FG. Uterine cervical carcinoma after therapy: CT and MRI imaging findings. Radio Graphics. 2003;23:969–81. doi: 10.1148/rg.234035001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bondt RB, Nelemans PJ, Bakers F, Casselman JW, Peutz-Kootstra C, Kremer B, et al. Morphological MRI criteria improve the detection of lymph node metastases in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Multivariate logistic regression analysis of MRI features of cervical lymph nodes. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:626–33. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1187-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eifel PJ, Berek JS, Markman MA. Cervical cancer. In: DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. pp. 1311–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayr NA, William S, Jr, Gaffney DK. Cervical Cancer. In: Lu JJ, Brady LW, editors. Decision Making in Radiation Oncology. Vol. 2. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 661–701. [Google Scholar]