Introduction

The efforts to complete sequencing of the human genome have enabled new endeavors into the function of these genes in human disorders and have provided a wealth of knowledge about the molecular underpinnings of behavior. However, sequencing and mapping represent the initial step in our understanding of gene function and how gene expression is related to our health. The next major challenge in biology is the utilization of this information to determine the function of the genes and proteins in the context of human disease. The advent of high-throughput screening technologies has produced a paradigm shift in the manner in which scientists are able to detect and identify molecular mechanisms related to disease. Procedures such as serial analysis of gene expression (Velculescu et al., 1995), differential display (Liang and Pardee, 1992) and cDNA sequencing (Okubo et al., 1992) enable the assessment of differential gene expression but have limited throughput when compared to microarrays. Microarray analysis offers an alternative strategy that allows the simultaneous assessment of thousands of genes of known function as well as expressed sequence tags (ESTs) with either one or multiple samples (Brown and Botstein, 1999; Schena et al., 1995).

The two most widely used types of arrays for gene expression analysis are the cDNA and oligo arrays, such as those produced by Affymetrix. Oligonucleotide arrays consist of multiple, yet distinct, representations (e.g 10-25 mers) of individual genes. The principle advantages of the technology are the specificity of hybridization of the oligonucleotides with target cDNA (enabling discrimination among gene family members as well as splice variants), the ability to perform both gene expression and single nucleotide polymorphism analysis using the same platform, good sensitivity in detection, and the ability to compare multiple array experiments post hoc. Alternatively, cDNA arrays consist of longer clone fragments (e.g. 300-2000 bases) with one to three representations of each gene on the array. (Schena et al., 1995; Derisi et al., 1996). The distinct advantages of this type of array are greater flexibility and lower relative cost and the availability of array spotters, scanners, and cDNA clones enables researchers to manufacture arrays to their respective specifications. Similar to oligo arrays, cDNA arrays can be used to make post hoc comparisons from multiple array experiments as well as to compare multiple samples on the same array.

To evaluate differential gene expression, complementary DNA (cDNA) or oligonucleotides are adhered to a solid support (ie. glass, nylon, plastic). During reverse transcription, cDNA is labeled with either radioactive (e.g. 32P/ 33P dCTP or dATP) or fluorescent tagged nucleotides (eg. Cyanine 3 and 5: Cy3 and Cy5) for individual or competitive hybridization strategies, respectively. The immobilized cDNA or oligos will hybridize with the complementary labeled cDNA, such that the intensity of the hybridization signal for a specific array spot will be representative of the abundance of that particular transcript in the tissue or cell from which the RNA was extracted originally.

DNA microarray technology provides a systematic parallel approach for investigating the simultaneous expression of thousands of genes - thereby enabling a global view of the multigenic nature of mental illnesses. To date, microarray analysis has been used to investigate differential gene expression in several areas of brain research including aging (Ly et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000; Weindruch et al., 2002), multiple sclerosis (Whitney et al., 1999, 2001) and Alzheimer’s Disease (Ginsberg et al., 1999, 2000). However, the utility of microarray analysis for the investigation of molecular correlates of psychiatric illness is only now being realized. Broad scale evaluations of gene expression using microarrays are well suited to the study of psychiatric illnesses, particularly in light of the complexity of the brain compared with other tissues, the multigenic nature of these illnesses, the large representation of expressed genes in the brain, and our relatively limited knowledge of the molecular pathology of these illnesses. Examples of microarray based gene expression analysis in schizophrenia and drug abuse in both human postmortem brain tissue and animal models are presented to illustrate the achievements and limitations encountered with microarray technology in studying psychiatric illnesses.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic, debilitating disease characterized by alterations in thought and behavior patterns that affects approximately 1% of the population. The clinical manifestations of schizophrenia are commonly divided into positive symptoms (hallucinations, formal thought disorder, paranoia and delusions) and negative symptoms (blunted affect, poverty of speech and social withdrawal). In addition, alterations in cognitive processes, especially working memory, have been demonstrated in several neuroimaging studies of schizophrenic patients. The cause of this disease is not well understood; evidence implicates genetic, environmental, developmental and nutritional factors. This multigenic etiology has complicated the task of identifying molecular substrates associated with schizophrenia. Indeed, it has been proposed that schizophrenia is a heterogeneous classification in which multiple causes can result in the same functional deficits. Whereas several studies have provided insight into the roles of particular genes, assessments have been limited to one or a few transcripts; however, the multigenic nature of schizophrenia is probably due to the coordinate dysregulation of several genes (Eberwine et al., 1998). This inherent complexity suggests that high-throughput genomic screening techniques, such as microarrays, may be well suited for identifying transcripts that are dysregulated in the disease state.

A primary difficulty in applying array technology to psychiatric illnesses is identification of the neurobiological substrates of the diseases, many of which remain either equivocal or elusive. For example, several brain regions have been implicate in the neuropathology of schizophrenia, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and thalamus. The dorsolateral PFC has received considerable research attention due to its intimate involvement in working memory and the apparent hypofunction of this region seen in schizophrenic patients [Weinberger, 1996]. Previous studies of gene expression changes in schizophrenia have revealed alterations in transcripts involved in neurotransmission (Akbarian 1995, 1996, Meador-Woodruff 1997, Volk 2000) and signaling cascades (Dean 1997, Shimon 1998, Hudson, 1999); however, nearly all studies to date have focused on one or several genes, rather than investigating global changes.

One of the first studies to use high-throughput screening to explore the molecular underpinnings of schizophrenia was undertaken by Mirnics and colleagues (2000), who used microarray analysis to provide a detailed “molecular profile” of the prefrontal cortex. The results of their work represent a significant advancement in our understanding of this disease and underscore the utility of the application of array technology to complex psychiatric disorders. For this study, mRNA was isolated from post-mortem tissue sections of the prefrontal cortex of six age-matched schizophrenic patients and controls, reverse-transcribed and labeled with Cy3 (control) or Cy5 (schizophrenia) fluorescent dyes. Labeled probes from pairs of controls and schizophrenics were combined and hybridized to high-density, commercially produced (Incyte Pharmaceuticals) microarrays containing 8700 human cDNAs. Results were analyzed by functional clustering in which genes are grouped according to their involvement in particular biochemical pathways or within a specific protein family. Results revealed a consistent down-regulation of transcripts related to presynaptic machinery (PSYN), as well as glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission. The authors focused on the decrease in PSYN transcripts as a group, noting that the specific genes and pattern of decrease differed across each subject. It is important to note that pairwise comparisons were made -- subjects were matched according to age and gender. Theoretically, this type of comparison could lead to identification of differentially expressed genes based on random variation between the two subjects, rather than a true alteration due to the disease. To further investigate the observed changes, the authors used in situ hybridization (ISH) for four of the differentially expressed PSYN genes: N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor (NSF) and synapsin II, which were the most consistently down-regulated across subjects, and synaptojanin 1 and synaptotagmin 5, which had a more variable profile depending on subject. Pairwise comparisons, identical to those used in the microarray experiment, confirmed changes identified from the arrays. ISH is commonly employed as a secondary screening method for arrays allowing the cellular localization of transcripts. However, precise quantification of ISH data is difficult due to differential tissue penetration of the probe and dispersion of probe signal. In addition, the use of full-length cDNA probes maintains the possibility of cross-hybridization among genes with sequence homology. Alternatively, transcript-specific oligos would provide specificity for the target of interest, with minimal opportunity for cross-hybridization among family members.

The potential contribution of antipsychotic administration on the molecular profile of schizophrenia was addressed in two ways. First, comparisons were made between two schizophrenic patients that were medication free at the time of death were compared with controls. Interestingly, decreased expression of the PSYN gene group was observed in these individuals, in a manner similar to that seen in PFC from medicated schizophrenics in this study. Second, gene expression was compared between the PFC of two pairs of haloperidol-treated rhesus monkeys and untreated rhesus monkeys. No significant differences were observed in the PSYN gene group using either microarray analysis or ISH leading to the conclusion that alterations in the PSYN genes are not the result of antipsychotic medication. Taken together, the results of the microarray and in situ hybridization studies performed by Minrics and colleagues show a consistent down-regulation of genes related to presynaptic machinery in the PFC of schizophrenics. The authors propose a working model of prefrontal pathology in schizophrenia that suggests a common abnormality in the regulation of presynaptic function, but specific differential combinations of genes that underlie this abnormality between subjects. This model is compatible with several other lines of evidence concerning developmental dysregulation of synaptic connections in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. For example, the age of onset of schizophrenia (adolescence) coincides with the end of Phase 5 of synaptic development in humans, during which there is large-scale synaptic pruning in the PFC (Huttenlocher 1979, 1997). Improper expression of PSYN genes during this stage could lead to dysfunction of developing neuronal circuits, which may in turn lead to deficits in cognitive processing as development continues.

Shortly after the publication of Mirnics et al. (2000), Hakak et al (2001) examined differential gene expression in the PFC of 12 schizophrenic patients compared with 12 normal controls used oligonucleotide arrays. The Affymetrix platform, as described above, does not utilize a competitive hybridization as do cDNA arrays; rather, labeled RNA from each subject is hybridized to a different chip, and comparisons are made post hoc. Data from this study were analyzed using hierarchical clustering, a method in which genes are grouped according to their levels of differential expression yielding a global assessment of coordinate changes in gene expression information about genes that may be under similar transcriptional regulation. Results of the arrays indicated 89 differentially expressed genes, with a consistent down-regulation of six genes that are related to the process of myelination (myelin and lymphocyte protein, gelsolin, 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase, myelin-associated glycoprotein, transferrin, and the neuregulin receptor ErbB3). The issue of antipsychotic involvement in observed gene changes was addressed by performing additional array experiments with tissue from four schizophrenic patients that had been medication-free between six weeks to two years. There was no significant difference between the non-medicated and medicated groups in expression for the 89 differentially expressed genes identified above. Thus, the authors concluded that observed deficits in myelination-related genes may not be associated with medication status. Unpaired two-group comparisons (t-tests) were used to compare expression levels of individual genes between control and schizophrenic groups. However, no adjustments to the p-value were made to account for the high number of comparisons. It is also important to note that no secondary screens (such as in situ hybridization) were used in this study to confirm the array-based findings. The process of myelination had not been implicated in schizophrenia prior to this paper, and the authors conclude that this may be a new area of investigation for the study of prefrontal dysfunction. Interestingly, myelination of the PFC occurs in late adolescence, the typical age of onset for schizophrenia (Benes, 1989). Also, demyelinating disorders can be associated with psychotic symptoms (Hyde, 1992), and imaging studies of schizophrenic patients show white matter abnormalities in the PFC (Lim, 1998). Specifically, the authors propose that oligodendrocytes, the cells that produce myelin, may be deficient in schizophrenia, and this could lead to slowed or abnormal neuronal processing.

These results are clearly different from the conclusions drawn from the Minrics study, and it is interesting and informative to compare the methodological approaches used in the two studies in hopes of understanding these discrepancies. The first major difference between the papers is the specific genes queried. For instance, only one of the six myelination-related genes found to be differentially expressed in the Hakak paper was present on the platform used by Minrics et al (2000). Additionally, Hakak et al. did observe changes in several genes related to pre-synaptic function, but did not mention whether the oligos were representative of the cDNAs assessed in the Minrics study. A second important difference between the two studies was the demographics of the sample populations. In the Mirnics study, schizophrenic patients were middle-aged (mean age = 46.5 ± 10.7 years), whereas the Hakak cohort was quite elderly (mean age = 72.1 ± 11.7 years). Thus, differences in reported results of these studies could be due to 1) alterations in myelination genes are present in older schizophrenics, 2) more prominent myelin dysregualtion during senescence, and/or 3) alterations in presynaptic machinery are more prevalent in younger patients. Additionally, the severity of the disease differed between the two cohorts of patients. In the Mirnics et al. study, clinical diagnosis of the subjects was prospectively accrued and subjects were community dwelling, indicating that the disease was either mild or well controlled. Comparatively, subjects in the Hakak et al. study were retrospectively accrued and consisted of chronically hospitalized patients, implying a more severe illness. Therefore, the observed differences could also be a function of disease progression or severity. Differences could also be attributed to subtle differences in the specific brain region dissected. Although both papers report studying the “prefrontal cortex”, the first group used frozen sections corresponding to Broadman’s area 9, while the second group dissected Broadman’s area 46 from frozen coronal blocks. While these two brain areas are both considered components of the prefrontal cortex, area 46 has a more well-defined role in working memory, whereas the function subserved by area 9 is not well understood. Therefore, it could also be that the changes found by the two studies reflect a regional specificity of schizophrenic pathology.

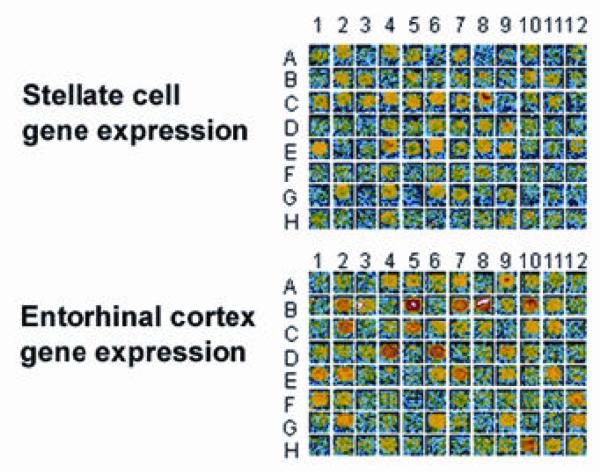

Regional assessments of gene expression create a mosaic of expression level changes; however, these expression profiles cannot discern changes occurring in the affected or target neuron from those occurring in adjacent neuronal and non-neuronal populations and would likely result in different gene expression profiles (Figure 1). Direct determination of the location and status of gene expression in single neurons obtained from human post-mortem brain tissue is optimal for hypothesizing molecular mechanisms that underlie the pathophysiology of disease – assuming there is evidence for the substrate. Single cell gene expression methodology combined with cDNA microarray technology can overcome some of the anatomical and molecular limitations by assessing multiple transcripts in “target” neuronal populations. Identifying molecular correlates of schizophrenia using regional analysis has been complicated by several factors, including clinical heterogeneity, cellular heterogeneity of cortical and subcortical regions as well as the difficulty in assessing multiple genes in discrete neuronal populations. The clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia is suggestive of complex anatomical and biochemical interactions; however, certain elements of the schizophrenia phenotype are likely mediated by common biological substrates.

Figure 1. Microarray panel comparing gene expression patterns for EC Layer II stellate neurons and EC region from human post-mortem tissue (Incyte UniGEM V).

Several genes expressed in stellate neurons were also expressed in EC at differing abundances (e.g. B2, C5 and B10). Some mRNAs detectable in the stellate neurons and not in EC, likely due to enrichment in stellate neurons (G7 and E4). In contrast, many mRNAs present in the EC were undetectable in stellate neurons, likely due to the heterogeneity of EC cell types and consequent dilution (B5, D4, H10). Red, highest expression; blue lowest expression.

Another brain region associated with schizophrenia is the temporal lobe, which includes the hippocampus, subiculum and entorhinal cortex (EC). The EC is integral to the function of the hippocampus, regulating the interaction of the hippocampus with other brain regions and disruption of neuronal functioning in this region could affect information processing between the hippocampus and various cortical areas. The EC brain region has been implicated in the pathology of schizophrenia through imaging studies of patients that revealed significant deficits in temporal lobe function (Gur, 1995). In addition, alterations in neuronal organization and connectivity in the temporal lobe represent a subtle neuropathological feature of the disease (Trojanowski and Arnold, 1995). Recently, Hemby et al.(2002) examined coordinate changes in the relative expression levels of >18,000 genes in EC Layer II stellate neurons from schizophrenic patients and age-matched, non-psychiatric controls using high-density cDNA microarrays. The strategic location of EC Layer II stellate neurons and the previously identified biological alterations in schizophrenia, including aberrant cytoarchitectural arrangement (Arnold et al., 1991, 1997; Jakob and Beckmann, 1986), normal neuron density but smaller neuron size (Arnold et al., 1995), and decreased expression of the microtubule-associated protein MAP2 (Arnold et al., 1991), make them an excellent candidate for probing disease-related differences in gene expression associated with schizophrenia. Brains from eight chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia (83.9 ± 3.5 years) and 9 age-matched neurologically normal controls (77.7 ± 4.1 years) were used. Schizophrenia subjects were elderly, “poor-outcome” patients who were chronically hospitalized. All patients were prospectively accrued and control subjects were without history of neurological or major psychiatric illness. The temporal lobe containing the EI subfield was blocked, ethanol fixed and embedded in paraffin. One section from each subject was stained with acridine orange to verify the presence of nucleic acids in the tissue (Figure 2). An adjacent section was immunostained with a monoclonal antibody to non-phosphorylated neurofilament (RmdO20; Lee et al., 1987) to identify individual neurons for subsequent single cell analysis. Following in situ transcription, Layer II stellate neurons were dissected and contents were amplified using aRNA amplification (Tecott et al., 1988; VanGelder et al., 1990; Eberwine et al., 1992). Under optimal conditions, the first round of aRNA amplification results in approximately 1000-fold yield while two rounds of amplification result in approximately 106 fold increase over the original amount of each poly(A+) mRNA in the native state of the neuron. The aRNA procedure is a linear amplification process with minimal change in the relative abundance of the mRNA population in the native state of the neuron. Furthermore, mRNA can be reliably amplified from small amounts of tissue including individual neurons (e.g. Ginsberg et al., 1999, 2000, Hemby et al., 2002). For initial screening of the high-density arrays (Incyte Pharmaceuticals; 8,700 genes), aRNA from six neurons from each of four schizophrenic patients and four controls were pooled, respectively (e.g. 24 neurons per condition for each array), prior to reverse transcription. An inclusion criterion for schizophrenics was based on the lack of antipsychotic medication for at least one year prior to death. cDNA from the schizophrenia group was labeled with Cy3 and the control group was labeled with Cy5 during reverse transcription. Data were analyzed according to specific protein families and biochemical pathways relevant to cellular function as well as to chromosomal loci implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Forced functional clustering of the data revealed marked differences in mRNA expression of various G-protein coupled receptor signaling transcripts, glutamate receptor subunits, synaptic proteins and other mRNAs between schizophrenics and controls, similar to results observed in the Mirnics et al. study (2000).

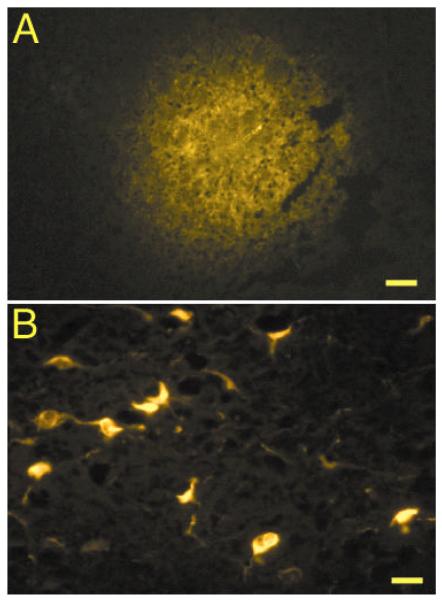

Figure 2. Representative acridine histofluorescence staining of CA1 pyramidal neurons from post-mortem human hippocampus.

Six micron section is from a non-psychiatric control subject under 20X magnification.

Candidate arrays were prepared on nylon membranes were performed to validate differential gene expression detected on the microarrays and to supplement the arrays by including genes from protein families that are underrepresented on the current microarray platforms. This secondary analysis revealed significant decreases in Giα1, GluR3, NMDAR1, synaptophysin, SNAP23, and SNAP25 in stellate neurons of schizophrenics. In addition, microarray analysis revealed the detection of phospholemman mRNA, a transcript heretofore undetected in human brain. Phospholemman, a phosphoprotein involved in the formation and/or regulation of a Cl− anion channel, was down regulated at the transcript and protein level.

Results from the Hemby et al. study have identified several possible mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction that may underlie aspects of schizophrenia. One such mechanism involves vesicular proteins involved in synaptic function. Levels of mRNAs encoding synaptic vesicle proteins (SVPs; synpatophysin, synaptotagmin I and IV) and synaptic plasma membrane proteins (SPMPs; SNAP23 and SNAP25) were found to be significantly decreased in EC Layer II stellate neurons of schizophrenics, whereas another plasma membrane protein syntaxin was upregulated over four-fold. The proteins encoded by these mRNAs serve different functions at different functional steps in the synaptic vesicle cycle and it is reasonable to conclude that alterations in the levels of the proteins encoded by these mRNAs may lead to decreased neurotransmitter release from the Layer II stellate neurons.

In agreement with Mirnics et al. (2001), glutamatergic dysfunction is yet another possible mechanism underlying the neuropathophysiology of schizophrenia, specifically, altered gene and protein expression of the ionotropic glutamatergic receptor. Results from this study support findings of decreased glutamate receptor mRNA expression in the hippocampal subfields (Eastwood et al., 1995) and temporal cortex (Humphries et al., 1996). Decreased abundance of ionotropic glutamate receptors may have profound downstream effects including alterations in excitatory neurotransmission and subsequent cognitive and behavioral sequelae mediated by glutamatergic circuitry. Future studies are warranted to characterize the glutamatergic ionotropic and metabotropic receptors as well as glutamatergic receptor interacting proteins (e.g. GRIPs, PSD95, SAP102 and homer).

Together, these studies represent a significant advance in the understanding of the molecular neuropathology of schizophrenia. However, future studies should examine protein levels of the genes that were differentially expressed in the disease state. The reliability of mRNA levels as an indicator of protein levels and the functional role of proteins in cellular function is variable. Translational accessibility, post-translational modifications, and phosphorylation states of proteins can all disrupt the balance between mRNA and functional protein. Western blot analysis or immunocytochemistry can be used to assess levels of specific proteins when antibodies are available, and would lend greater functional relevance to the results of the above studies. In addition, it is probable that genes not included on the microarrays or selected as candidate genes are regulated in the disease state. A lack of differential expression does not imply that a respective protein is not involved or vice versa that a differentially expressed mRNA is involved. Secondary experiments that directly manipulate levels of transcripts and proteins are essential to make that assessment. Future studies should also evaluate alterations in gene expression in other brain regions, both those implicated in the schizophrenia as well as regions that do not exhibit functional dysregulation in the disease. In the years to come, the focus of functional genomics approaches to schizophrenia, as well as other psychiatric diseases, should shift from regional to targeted cell assessment to provide a more refined and detailed evaluation of molecular alterations in this disease. In addition, evaluation of different cell populations within a particular region may provide insight into particular cell vulnerabilities that are correlated with the disease. Finally, studies should begin to incorporate the large amounts of clinical data available about subjects used in microarray analysis. Correlating clinical and molecular data may allow for identification of specific expression profiles or gene changes associated with particular facets of the disease.

Drug Abuse

The 1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse estimated 1.8 million Americans were current cocaine users, 595,000 frequent users and 2.4 million occasional users. With no significant decreases since 1992, these figures represent a persistent problem (NCADI, 1998). Understanding the neural mechanisms that mediate cocaine abuse is critical for improving existing therapies and developing new treatment therapies. Chronic cocaine use results in a particularly intense euphoria and persistent drug dependence. In humans, the propensity to use cocaine is influenced by both positive (euphoric, pleasurable effects) and negative (withdrawal, depressed mood states and drug cravings) consequences, including the development of neuroadaptive changes in specific brain regions (Gawin et al., 1991). The neurobiological and molecular characteristics of cocaine addiction, although specific to cocaine, may generalize to other drug dependencies. Current understanding on the neuroadaptive processes stemming from chronic cocaine administration is based largely on animal models of human drug taking, such as intravenous self-administration. However, the direct determination of the location and status of gene expression in human post-mortem tissues is essential for understanding the effects of chronic cocaine on the molecular pharmacology of dopaminergic pathways in the human brain. Although there are many difficulties with post-mortem brain studies, it is one of the most promising ways to view biochemical changes that are relevant to human drug abusers and to educate the public about the consequences of cocaine abuse.

Similar to schizophrenia, drug abuse is a heterogeneous disorder with multiple causes all of which can lead to the same functional endpoint – namely addiction. While the regulation of individual transcripts have been suggested as mediators of the addictive process, a more likely scenario is that the coordinate expression of multiple genes in defined neuroanatomical loci are either the mediators of addictive behaviors or are modulated by chronic drug use. The reinforcing effects of all abused drugs are mediated by the mesolimbic dopamine system that originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projects to several basal forebrain regions including the nucleus accumbens (NAc), ventral caudate-putamen, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, diagonal band of Broca, olfactory tubercles, prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices. Administration of drugs that are abused by humans lead to activation of this pathway in humans, non-human primates and rodents (Porrino, 1993; Lyons et al., 1996; Volkow et al., 1997). Activation of this circuit has been correlated with subjective reports of craving and euphoria in cocaine addicts (Volkow et al., 1997; Childress et al., 1999).

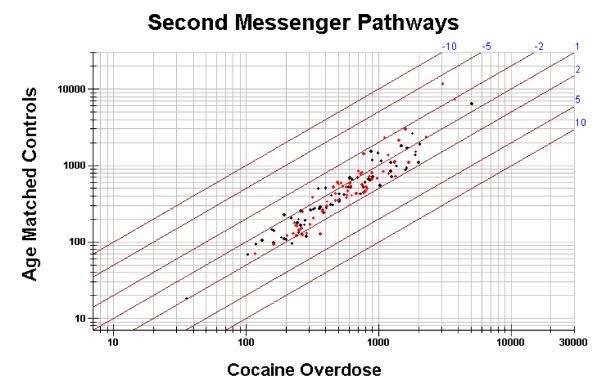

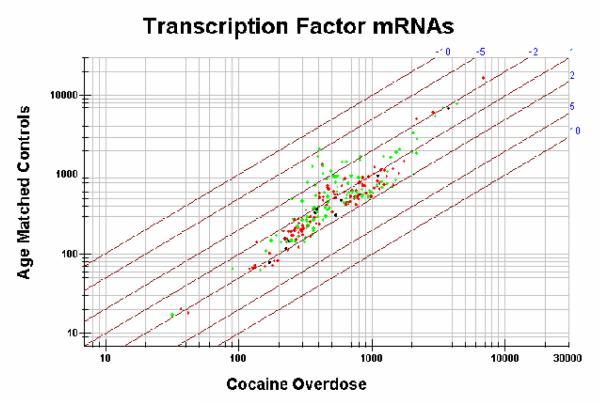

Currently, studies have been undertaken to identify genes that are differentially regulated in the VTA of cocaine overdose victims (Hemby, unpublished). Gene expression from VTA between cocaine overdose victims (n=6) and age-matched controls (n=5) has been compared using high-density microarrays (UniGEM V. 2.0, Incyte Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). Equivalent concentrations of mRNA from each subject within the cocaine overdose group or the control group were pooled, respectively. Pooling samples decreases the influence of individual variability and stresses the identification of those transcripts that are most highly regulated in sample population. However, a pitfall with this approach is that individual variations in gene expression within each group will not be identified. Results from the initial study provide the first gene expression profile of cocaine addiction in humans (>8700 genes). Using two-fold differential expression as a cut-off for the hierarchical analysis, >200 transcripts are down-regulated and >350 transcripts are up-regulated in the VTA from cocaine overdose victims. Subsequently, functional clustering was used to assess differential gene expression in biochemical pathways (e.g. cAMP and phosphoinositol pathways), protein families (e.g. dopamine receptors), protein motifs (e.g. zinc finger, leucine zipper, etc.) and transcripts related previously to cocaine abuse in humans and animal models. As noted, several animal studies have suggested that chronic cocaine exposure results in significant alterations in the cAMP pathway. However, scattergram analysis of representative transcripts in these pathways indicates slight dysregulation in the cAMP pathway and considerably less in the phosphoinositol pathway as assessed by differential gene expression (Figure 3). The contribution of transcription factors to neuroadaptive mechanisms in the VTA and the manner in which they are induced by chronic cocaine remains unanswered. Phosphorylation of transcription factors can result in rapid and selective gene transcription, thereby providing a means by which receptor activation can regulate gene expression and the long-term changes associated with chronic cocaine use. Of the protein families investigated to date, the general class of transcription factors (leucine zipper, zinc finger and homeobox genes) appear to be the most highly dysregulated class of genes evaluated to date (Figure 4). Studies are underway to assess the degree of differential expression in each subject as well as to understand the role of each of these proteins in transcriptional regulation (transfection in cell lines and comparative expression analysis).

Figure 3. Scattergram plot of differential expression of mRNA in cAMP (red) and phosphoinositol (black) second messenger pathways from the VTA of cocaine overdose victims and age-matched controls.

cAMP pathway includes G-protein subunits, protein kinases, adenylate cyclase subunits and others. Phosphoinositol pathway clones include phospholipase C subunits, protein kinase C, IP3 receptors and others. Lines represent fold differential expression (2, 5 and 10 fold differences).

Figure 4. Scattergram plot of differential expression of transcription factors from the VTA of cocaine overdose victims and age-matched controls.

Transcript classification is based on UniGene gene name for specific accession numbers. Homeobox genes (black), leucine zipper (red) and zinc finger (green). Lines represent fold differential expression (2, 5 and 10 fold differences).

Reverse Northern analysis was used as the secondary screen for 192 transcripts that were identified as differentially expressed (>2 fold) in the high-density microarray or as candidate genes that did not appear on the Incyte microarray. Preliminary data are consistent with neuroadaptive responses in intracellular signaling cascades associated with long-term cocaine-induced stimulation of dopamine receptors, although the relatively small number of dopamine-related genes represented on commercially available arrays has limited our interpretations. Therefore, a battery of genes encoding dopamine- and signal transduction related proteins were included for the reverse Northern analysis to determine the pattern of gene expression and indicate whether the VTA in cocaine overdose victims is preferentially affected as a consequence of long-term cocaine use. mRNA from each subject for each group was hybridized separately to two reverse Northern blots each containing 96 candidate clones.

Secondary screening revealed significant alterations in the expression of multiple genes and of several function-related gene groups. Due to the plethora of substance abuse literature implicating monoamine receptors, enzymes, and transporters as well as second messenger cascades, we present data indicating altered expression of several transcripts involved in intracellular signaling. Additional data implicate other receptor systems (GABA-A receptor subunits, GABA-B receptor, glutamate receptors, transcription factors, etc.). Complementary to previously published results, we did not observe significant alteration in the D2 dopamine receptor (Moore et al., 1998), dopamine transporter, tyrosine hydroxylase (Sorg et al., 1993; Vrana et al., 1993; Burchett and Bannon, 1997) or in serotonin receptor subytpe 2C or 3 mRNA levels.

Additional analyses at the protein level indicated an upregulation of CREB in the VTA, but not in the lateral substantia nigra. These preliminary data are consistent with a dysregulation of dopamine receptor-coupled signal transduction pathways including specific components of the cAMP pathway in the mesolimbic dopamine system. In addition, these results are the first attempt to delineate molecular markers indicative of neuroadaptive responses in the mesolimbic dopamine system in human post-mortem tissue from cocaine overdose victims.

Understanding the consequences of long-term cocaine abuse on post-mortem brain tissues requires vigorous investigation. These types of studies reveal whether the regulatory adaptations that occur in rodents and monkeys are applicable to human brain, and will reveal which changes are state or trait markers in human drug abusers. Findings in post mortem brain tissues often provide the first leads that can be investigated in living brain. Examples include the loss of DA in Parkinson’s disease (Kish et al 1988, 1992), changes in the DAT (e.g. Little et al., 1993a,b; Staley et al., 1994a,b; Hitri et al., 1994) or opiate system (e.g. Hurd and Herkenham, 1993; Staley et al., 1997) with chronic cocaine exposure, and the down-regulation of the nicotinic ACh receptor after chronic nicotine (Breese et al., 1997). Although there are many difficulties with post mortem brain studies, it is one of the most promising ways to view biochemical changes that are relevant to human drug abusers and to educate the public about the consequences of cocaine abuse. Whereas animal studies have advanced our understanding of the neurobiological basis of drug addiction, the evaluation of similar questions in human tissue are few, yet essential. By assessing changes in defined biochemical pathways in human post-mortem tissue, we can begin to ascertain the fundamental molecular and biochemical processes that are associated with long-term cocaine use. Neuroadaptive changes in the human brain post-mortem reflect chronic cocaine abuse, since death in a naive user is a rare occurrence, and the cohort of post-mortem subjects have many surrogate measures of chronicity. Understanding gene expression patterns in post mortem tissue from cocaine overdose victims represents a promising avenue to further understanding the molecular mechanisms related to the long-term consequences of cocaine abuse. Results from this and similar studies will provide the “molecular fingerprint” of cocaine addiction and may provide novel targets for pharmacotherapeutic intervention. Moreover, this information can be used to further develop experimental animal models in which these genetic alterations could lead to a further understanding of biochemical and behavioral alterations associated with cocaine abuse.

One of the first published reports on array analysis of drug abuse evaluated the effects of cocaine on gene expression in the NAc (Freeman et al., 2001a). Rhesus monkeys (n=4) were administered cocaine chronically by an experimenter over a one-year period. Total RNA was extracted from the NAc of each subject and pooled according to group (cocaine or control). Following reverse transcription, 32P labeled cDNA probes were generated from the pools and used to screen duplicate Atlas Human 1.2 Array from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) containing 1176 cDNAs. Noting the inherent difficulties with cross-species hybridization of monkey cDNA with human clones, such an approach appears warranted at the present time due to the lack of available non-human primate arrays and cDNA libraries. However, in the present study, cross-hybridization is complicated by the use of gene specific proprietary primers in the Clontech protocol and the lack of available sequence for rhesus monkeys. Future studies should address the homology of human and rhesus monkey genes under investigation and the specificity of the primers in species other than humans. Nonetheless, duplicate array analysis revealed several changes (>2 fold) in gene expression due to cocaine treatment including the α subunit of protein kinase A, β subunit of cell adhesion tyrosine kinase, mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 1, and β-catenin. Differential expression of the four selected genes was confirmed at the protein level by immunoblotting, with all four candidates showing significant upregulation in the cocaine treated monkeys. The authors point out that differential expression of these candidate markers contributes to a signaling scheme responsible for the induction of multiple genes, including c-fos, c-jun and CREB proteins. Results from this study complement and extend previous studies implicating an up-regulation of the cAMP second messenger system in the effects of chronic cocaine, for the first time demonstrating such changes in a non-human primate model. Additional studies are warranted to determine if similar changes are observed in post-mortem tissue of cocaine abusers and if similar changes occur in monkeys that are self-administering cocaine.

In a second study, Freeman et al. (2001b) assessed the effects of cocaine administration on hippocampus gene expression in rats. The hippocampus is known to be involved in learning and memory and is considered a probable locus for the effects of cocaine associated with “craving” and relapse (Vorel and Breiter). Rats received three non-contingent (experimenter administered) injections of cocaine (15 mg/kg; i.p.) for 14 days. Total RNA was extracted from the hippocampus each subject and pooled according to group (cocaine or control). Following reverse transcription, 32P labeled cDNA probes were generated from the pools and used to screen duplicate Rat Atlas Image 1.2 Arrays from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) containing 1176 cDNAs. Although there was an approximate 2 fold increase in the number of genes with discernable signals in the second replicate, five genes exhibited a 2 fold up-regulation following cocaine administration (survival or motor neuron: SMN, metabotropic glutamate receptor 5: mGluR5; organic anion transporter polypeptide 2: OATP2; α subunit of protein kinase C: PKCα; and the α1 inhibitory subunit of guanine nucleotide binding protein: Giα1) whereas no genes were determined to be downregulated. Secondary analysis of the array data at the protein level using immunoblotting revealed significant increases in mGluR5 and PKCα, but not in SMN, Giα1, or OATP2. Several additional proteins were evaluated based on interesting (although below threshold) array candidates as well as proteins shown to be related to cocaine’s effects in the aforementioned study (Freeman et al., 2001a). The shaker related voltage gated potassium channel (Kv1.1), β catenin, α subunit of protein kinase A and the ε subunit of protein kinase C were shown to be upregulated in the hippocampus of cocaine treated rats. The lack of agreement between transcript and protein levels in this study could be related to several factors including differential localization of protein and mRNA, and post-translational modifications. The authors also put forth the possibility that the observed changes in mRNA may be due to procedural variability. Approaches to addressing this concern include assessment of mRNA (in situ hybridization, real time quantitative PCR and slot blot analysis) from individual subjects and the use of standard inferential statistical approaches to evaluate significant differences. More probable, the discrepancies between mRNA and protein levels in this study are a combination of several, if not all, of these factors. Similar to the previous study, these results extend previous studies implicating an up-regulation of the cAMP second messenger system in the effects of chronic cocaine administration. Additional studies are needed to determine the regional and species specificities of the reported transcripts and respective proteins as well as evaluation of such changes in an animal model that recapitulates drug taking in humans.

Experimental approaches to the investigation of the biological basis of drug abuse must take these essential questions to task when attempting to discern the relationship of biological changes to drug abuse. A generally accepted tenet in drug abuse research is that drugs can function as reinforcing stimuli in humans and animals and the reinforcing effects of these drugs contribute to their abuse liability. Therefore, when attempting to explore the biological basis of drug abuse, principle characteristics of human drug intake should be closely modeled, most notably, behaviors should be 1) contingent upon the delivery of the drug, 2) engendered and maintained by drug delivery, and 3) the frequency of those behaviors should be increased by drug delivery. Unlike other paradigms including non-contingent drug administration, self-administration meets all of these criteria. The majority of studies investigating the biological basis of drug addiction have utilized non-contingent drug administration and extrapolated the relevance of those finding to mechanisms of reinforcement. However, a growing body of literature has demonstrated significant differences resulting from the context and contingency of drug administration (Hemby et al., 1995, 1997a,b; Hemby 1999a; Wilson et al., 1994) suggesting that inferences to reinforcement drawn from studies using non-contingent drug administration may be misleading.

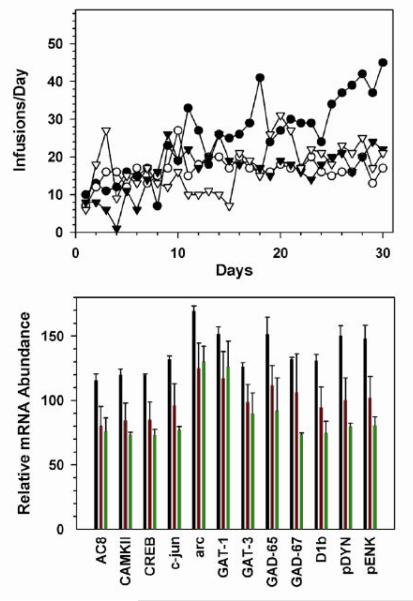

Recently, our lab has embarked on a series of studies to assess changes in gene expression levels of multiple cAMP pathway proteins in NAc medium spiny neurons during morphine self-administration. Several studies indicate the NAc as a principle substrate in opiate reinforcement, albeit dopamine does not appear to play a central role (Hemby et al., 1995, 1996, 1999b). GABAergic MSNs comprise approximately 95% of the NAc neuronal population and recent studies have demonstrated the presence of mu opiate receptor protein and mRNA in these neurons (Preston et al., 1979; Gerfen 1988; Smith and Bolam, 1990; Svingos et al., 1997). The accumbens-pallidal pathway is a major afferent projection of the NAc that appears to be an important substrate for opiate reinforcement as destruction of this pathway significantly attenuates heroin and morphine self-administration in rats (Zito et al., 1985; Dworkin et al., 1988b; Hubner and Koob, 1990). Due to the percentage of MSNs in the NAc, it is likely that the up-regulation in the cAMP pathway occurring as a result of chronic morphine administration is attributable in part to this neuronal population. Following induction of physical dependence, rats were trained to self-administer morphine (SA) or receive yoked morphine (YM) or saline (YS) infusions. The triad paradigm allows comparisons between the reinforcing effects (SA vs. YM) and direct pharmacological effects (YM vs. YS) of morphine in the presence of physical dependence. Rats maintained relatively stable rates of morphine self-administration (1.5 mg/infusion) for the 30 days (Figure 5a). Following 30 days of continuous access, rats were sacrificed and brains were cryostat sectioned (8 μm) from the rostral pole to the caudal aspects of the NAc. Sections were immunohistochemically stained with a monoclonal antibody against calbindin (calbindin D28k, SWANT antibodies) and the mRNA was transcribed in situ. Individual calbindin-immunoreactive neurons were dissected from the medial NAc shell and lateral NAc core. cDNA from five neurons/region/subject were pooled for analysis. Quantitative assessment of 32 genes either implicated in neuroadaptive response to chronic morphine or related to GABAergic function was performed by aRNA amplification of individual NAc shell MSNs combined with reverse Northern analysis.

Figure 5. Single cell molecular analysis of morphine self-administration.

Number of infusions per day for rats self-administering morphine (1.0 mg/infusion; intravenous). Data are presented for the SA subjects. YM and YS did not exhibit significant responding over the course of the experiment. (Top Panel). Effects of morphine administration on gene expression in NAc shell medium spiny neurons (Bottom Panel). SA: self-administering; YM: yoked morphine; YS: yoked saline.

As hypothesized, several members of the cAMP pathway were up-regulated (CREB, adenylate cyclase VIII and Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II) and GABA synthetic enzymes (GAD-65 and GAD-67), GABA transporters (GAT-1 and GAT-3) and a down-regulation of BDNF mRNA (data not shown). Similar patterns of expression are observed with proenkephalin, prodynorphin and c-jun, all of which have been implicated as CREB-regulated transcripts (Figure 5b). It is important to note that GFAP mRNA hybridization intensity was not above background, suggesting the mRNA was derived neuronally with minimal disruption of surrounding neuropil. Interestingly, mRNA levels were greater in the SA than the YM subjects, suggesting that these transcripts are regulated to a greater extent as a function of the reinforcing effects of morphine. It is important to mention that no changes in expression levels were observed for the opiate receptors (mu, delta and kappa) or the dopamine receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4). Preliminary data support and extend results indicating an up-regulation of cAMP pathway proteins in the NAc following morphine exposure by demonstrating regulation at the mRNA level within a defined neuronal population. In addition, mRNA levels of several cAMP pathway proteins, as well as others, are increased in the self-administering subject suggesting their potential involvement in the reinforcing effects of morphine.

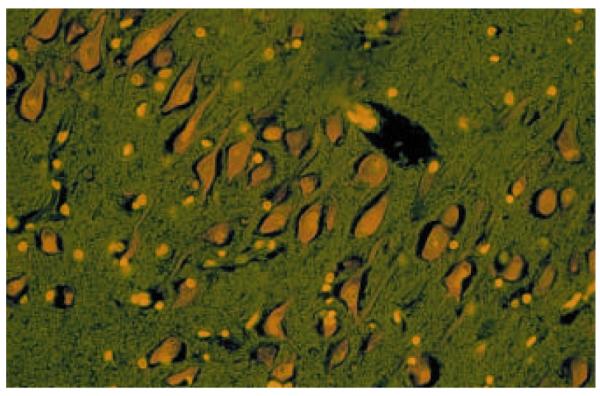

In attempts to further refine our molecular neuroanatomical approaches, our lab has begun combining retrograde tracing with laser capture microdissection and single cell gene amplification technologies. These procedures will enable the identification of discrete cell populations based on axonal projection targets and provide a heretofore unattainable level of anatomical resolution when investigating transcriptional regulation in defined neuronal pathways. One such study involves the evaluation of differential gene expression in mesoaccumbens neurons following cocaine self-administration in rats. FluoroGold was injected into the NAc prior to the beginning of intravenous cocaine self-adminsitration (1.0 mg/kg/infusion). Following 30 days of stable self-administration, rats were sacrificed and the brains were removed, blocked and paraffin embedded. Sections were cut through the NAc to evaluate the injection site (Figure 6) and through the VTA to assess tracer localization. Following in situ transcription, FluoroGold-positive cells were microdissected, RNA was amplified, as described previously. Figure 7 shows the ability to isolate specific cell populations and to successfully amplify RNA from the labeled cells. This approach provides an increased level of specificity compared with standard cellular recognition based on morphology and/or immunohistochemical approaches commonly used with microdissection.

Figure 6. Fluorogold labeling of VTA neurons from NAc.

(A) NAc injection site resulting from iontophoretic application of Fluorogold in cacodylate buffer using 5 mA of pulse current for 10 min. (B) Retrogradely labeled cells within the VTA after iontophoretic injection seen in (A). Bars equal 100 μm in (A) and 20 μm in (B). Diffusion pattern and labeling are similar to Schmued and Heimer (1990).

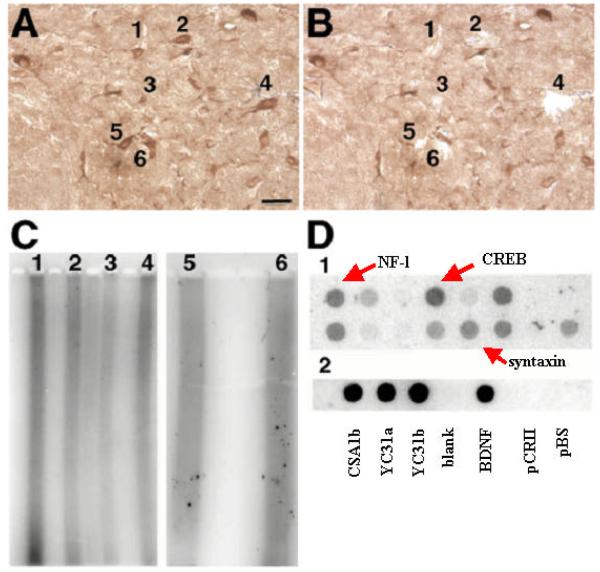

Figure 7. Single cell gene expression of Fluorogold labeled VTA neurons from rat cocaine self-administration.

Fluorogold was injected into NAc for labeling of VTANAc dopamine neurons. Following immunostaining with mouse anti-fluorogold antibody and in situ transcription, FG positive individual neurons were microdissected. A representative section is presented in Panels A (before) and B (after). Bar represents 20 μm. Two rounds of aRNA amplification amplified material from individual neurons and 32P-CTP labeled aRNA was run on a 1% denaturing gel (Panel C; numbers above lanes correspond to neurons in Panels A and B). Radiolabeled aRNA from neuron #2 was then used to probe candidate cDNAs adhered to nylon membranes (Panel D1) and subcloned differential display products (Panel D2). Hybridization intensity reflects abundance of corresponding mRNA. Panel C1, top row: neurofilament-L; casein kinase II b; H67559; AA069725; T89891; AA076650; pulmonary surfactant associate protein (control); heme oxygenase 1 (control); Panel C1, bottom row: CG1 protein precursor; H89874; H70730; H89236; syntaxin; T92612; T90579; stathmin. Numbers correspond to accession numbers. Panel C2: blank; CSA1b; YC3EA; YC3EB; blank; brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); vector (pCR II); vector (pBS). Note CSA1b, YC3EA, and YC3EB are novel transcripts subcloned from PCR differential display libraries.

Although significant advances have been made in the identification of neurochemical and neurobiological substrates involved in the behavioral effects of abused drugs, the relationship between these effects and resultant alterations in gene expression remains in its infancy. Growing evidence indicates that long-term drug use elicits neuroadaptive changes in various brain regions, effects likely mediated by alterations in the expression of multiple genes. However, the relationship between altered gene expression and the reinforcing effects of the specific drug classes remains understudied. The application of this information to the development of treatment strategies has not been fruitful for several reasons. One explanation is that research in the areas of neurobehavioral pharmacology and molecular biology has proceeded in relative isolation of each other. To date, there have been few published studies combining models of drug reinforcement (e.g. self-administration) with molecular biological approaches (e.g. assessment of gene expression). Other possible explanations include 1) the inappropriate use of experimental models, 2) reliance on non-neuronal systems or neuronal tissue not directly involved in the reinforcing effects of the drug, 3) the lack of definable neural substrates at the cellular or biochemical level and 4) the relative paucity of studies correlating changes in human postmortem tissue of drug overdose victims with animal models. The combination of appropriate behavioral models of drug reinforcement, specific neurobiological systems and state of the art molecular techniques will provide the most pertinent data for understanding the molecular basis of drug reinforcement and for potentially establishing novel targets for pharmacotherapeutic intervention. Understanding the effects of drug intake on the control of gene expression and the resultant cellular alterations represents a promising avenue to further understand the cellular mechanisms related to drug abuse and addiction. A more detailed understanding of the molecular and biochemical cascades in specific neuronal populations and the interactions between well defined neuronal populations within discrete brain regions could lead to a greater knowledge of the basic neurobiological processes involved in drug reinforcement. The integration of basic neuroscience and behavior offers the most productive avenue for delineating the complexity of the neurobiological underpinnings of drug reinforcement and the subsequent development of effective pharmacotherapies to treat addiction.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA13234, DA13772, SEH), the Stanley Foundation (SEH), and the National Alliance for Autism Research (SEH).

References

- Akbarian S, Huntsman MM, Kim JJ, Tafazzoli A, Potkin SG, Bunney WE, Jr., Jones EG, Investigator: Bloom FE GABAA receptor subunit gene expression in human prefrontal cortex: comparison of schizophrenics and controls. Cereb. Cortex. 1995;5:550–560. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.6.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarian S, Sucher NJ, Bradley D, Tafazzoli A, Trinh D, Hetrick WP, Potkin SG, Sandman CA, Bunney WE, Jr., Jones EG. Selective alterations in gene expression for NMDA receptor subunits in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:19–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00019.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Franz BR, Gur RC, Gur RE, Shapiro RM, Moberg PJ, Trojanowski JQ. Smaller neuron size in schizophrenia in hippocampal subfields that mediate cortical-hippocampal interactions. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152:738–748. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Han L-Y, Ruscheinsky DD. Further evidence of cytoarchitectural abnormalities of the entorhinal cortex in schizophrenia using spatial point pattern analyses. Biol. Psychiatry. 1997;42:639–647. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Hoesen GWV, Damasio AR. Some cytoarchitectural abnormalities of the entorhinal cortex in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1991a;48:625–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310043008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Lee VM, Gur RE, Trojanowski JQ. Abnormal expression of two microtubule-associated proteins (MAP2 and MAP5) in specific subfields of the hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1991b;88:10850–10854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM. Myelination of cortical-hippocampal relays during late adolescence. Schizophr. Bull. 1989;15:585–593. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese CR, Marks MJ, Logel J, Adams CE, Sullivan B, Collins AC, Leonard S. Effect of smoking history on [3H]nicotine binding in human postmortem brain. J. Pharmaco.l Exp. Ther. 1997;282:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PO, Botstein D. Exploring the new world of the genome with DNA microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:33–37. doi: 10.1038/4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchett SA, Bannon MJ. Serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine transporter mRNAs: heterogeneity of distribution and response to ‘binge’ cocaine administration. Mol. Brain. Res. 1997;49:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O’Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B, Opeskin K, Pavey G, Hill C, Keks N. Changes in protein kinase C and adenylate cyclase in the temporal lobe from subjects with schizophrenia. J. Neural Transm. 1997;104:1371–1381. doi: 10.1007/BF01294738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR. Genomics and array technology. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 1999;11:76–79. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199901000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SI, Guerin GF, Goeders NE, Smith JE. Kainic acid lesions of the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuate morphine self-administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;29:175–181. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood SL, McDonald B, Burnet PW, Beckwith JP, Kerwin RW, Harrison PJ. Decreased expression of mRNAs encoding non-NMDA glutamate receptors GluR1 and GluR2 in medial temporal lobe neurons in schizophrenia. Mol. Brain Res. 1995;29:211–223. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00247-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberwine J, Crino P, Arnold S, Trojanowski J, Hemby S. Psychopharmacology: Fifth Generation of Progress. CD-ROM version Lippincott-Raven Press; New York: 1998. Molecular analysis of the single cell: importance in the study of psychiatric disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Eberwine J, Yeh H, Miyashiro K, Cao Y, Nair S, Finnell R, Zettel M, Coleman P. Analysis of gene expression in single live neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1992;89:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman WM, Brebner K, Lynch WJ, Robertson DJ, Roberts DC, Vrana KE. Cocaine-responsive gene expression changes in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2001b;108:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman WM, Nader MA, Nader SH, Robertson DJ, Gioia L, Mitchell SM, Daunais JB, Porrino LJ, Friedman DP, Vrana KE. Chronic cocaine-mediated changes in non-human primate nucleus accumbens gene expression. J. Neurochem. 2001a;77:542–549. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH. Cocaine addiction: Psychology and neurophysiology. Science. 1991;251:1580–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.2011738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. Synaptic organization of the striatum. J. Electron Microsc. Technol. 1988;10:265–281. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg SD, Crino PB, Hemby SE, Weingarten JA, Lee VM, Eberwine JH, Trojanowski JQ. Predominance of neuronal mRNAs in individual Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg SD, Hemby SE, Lee VM, Eberwine JH, Trojanowski JQ. Expression profile of transcripts in Alzheimer’s disease tangle-bearing CA1 neurons. Ann. Neurol. 2000;48:77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE. Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. 4th ed Raven Press; New York, NY: 1995. Functional brain-imaging studies in schizophrenia; pp. 1185–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, Haroutunian V, Fienberg AA. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4746–4751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Co C, Koves TR, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. Differences in nucleus accumbens extracellular dopamine concentrations between response-dependent and response-independent cocaine administration. Psychopharmacology. 1997b;133:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Dworkin SI, Johnson BA. Neuropharmacological basis of drug reinforcement. In: Johnson BA, Roache JD, editors. Drug Addiction and Its Treatment: Nexus of Neuroscience and Behavior. Raven Press; New York: 1997a. pp. 137–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Martin TJ, Co C, Dworkin SI, Smith JE. The effects of intravenous heroin administration on extracellular nucleus accumbens dopamine concentrations as determined by in vivo microdialysis. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 1995;273:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. The effect of eticlopride and naltrexone on responding maintained by food, cocaine, heroin and cocaine/heroin combinations in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 1996;277:1247–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Co C, Dworkin SI, Smith JE. Synergistic elevations in nucleus accumbens extracellular dopamine concentrations during self-administration of cocaine/heroin combinations (Speedball) in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 1999a;288:274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE. Recent advances in the biology of addiction. Curr. Psychiatry Reports. 1999b;1:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s11920-999-0026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Ginsberg SD, Brunk B, Trojanowski JQ, Eberwine JH. mRNA expression profile for schizophrenia: single-neuron transcription patterns from the entorhinal cortex. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.631. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitri A, Casanova MF, Kleinman JE, Wyatt RJ. Fewer dopamine transporter receptors in the prefrontal cortex of cocaine users. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;151:1074–1076. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner CB, Koob GF. The ventral pallidum plays a role in mediating cocaine and heroin self-administration in the rat. Brain Res. 1990;508:20–29. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91112-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson C, Gotowiec A, Seeman M, Warsh J, Ross BM. Clinical subtyping reveals significant differences in calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 activity in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries C, Mortimer A, Hirsch S, de Belleroche J. NMDA receptor mRNA correlation with antemortem cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2051–2055. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199608120-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Herkenham M. Molecular alterations in the neostriatum of human cocaine addicts. Synapse. 1993;13:357–369. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR, Dabholkar AS. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;387:167–178. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971020)387:2<167::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR. Synaptic density in human frontal cortex - developmental changes and effects of aging. Brain Res. 1979;163:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde TM, Ziegler JC, Weinberger DR. Psychiatric disturbances in metachromatic leukodystrophy. Insights into the neurobiology of psychosis. Arch. Neurol. 1992;49:401–406. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530280095028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob H, Beckmann H. Prenatal developmental disturbances in the limbic allocortex in schizophrenics. J. Neural Trans. 1986;65:303–326. doi: 10.1007/BF01249090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:876–880. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene-expression profile of the ageing brain in mice. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:294–297. doi: 10.1038/77046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VM, Carden MJ, Schlaepfer WW, Trojanowski JQ. Monoclonal antibodies distinguish several differentially phosphorylated states of the two largest rat neurofilament subunits (NF-H and NF-M) and demonstrate their existence in the normal nervous system of adult rats. J Neuroscience. 1987;7:3474–3488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03474.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Pardee AB. Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992;257:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KO, Adalsteinsson E, Spielman D, Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of cortical gray and white matter in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998;55:346–352. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KY, Kirkman JA, Carroll FI, Breese GR, Duncan GE. [125I]RTI-55 Binding to cocaine-sensitive dopaminergic and serotonergic uptake sites in the human brain. J. Neurochem. 1993a;61:1996–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KY, Kirkman JA, Carroll FI, Clark TB, Duncan GE. Cocaine use increases [3H]WIN 35428 binding sites in human striatum. Brain Res. 1993b;628:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90932-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly DH, Lockhart DJ, Lerner RA, Schultz PG. Mitotic misregulation and human aging. Science. 2000;287:2486–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons D, Friedman DP, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Cocaine alters cerebral metabolism within the ventral striatum and limbic cortex of monkeys. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1230–1238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01230.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL, Watson SJ. Dopamine receptor transcript expression in striatum and prefrontal and occipital cortex. Focal abnormalities in orbitofrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:1089–1095. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnics K, Middleton FA, Marquez A, Lewis DA, Levitt P. Molecular characterization of schizophrenia viewed by microarray analysis of gene expression in prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2000;28:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RJ, Vinsant SL, Nader MA, Porrino LJ, Friedman DP. Effect of cocaine self-administration on dopamine D2 receptors in rhesus monkeys. Synapse. 1998;30:88–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<88::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. 1998 Website: http://www.health.org/pubs/nhsda/98hhs/findings/4cocaine.htm.

- Okubo K, Hori N, Matoba R, Niiyama T, Fukushima A, Kojima Y, Matsubara K. Large scale cDNA sequencing for analysis of quantitative and qualitative aspects of gene expression. Nat. Genet. 1992;2:173–179. doi: 10.1038/ng1192-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino LJ. Functional consequences of acute cocaine treatment depend on route of administration. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:343–351. doi: 10.1007/BF02244931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston RJ, Bishop GA, Kitai ST. Medium spiny neuron projections from the rat striatum: an intracellular horseradish peroxidase study. Brain Res. 1980;183:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC. Anterograde and retrograde neuroanatomical tract tracing with fluorescent compounds. Neurosci. Protocols. 1994;50:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shimon H, Sobolev Y, Davidson M, Haroutunian V, Belmaker RH, Agam G. Inositol levels are decreased in postmortem brain of schizophrenic patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;44:428–432. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Bolam JP. The neural network of the basal ganglia as revealed by the study of synaptic connections in identified neurones. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90106-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg BA, Chen SY, Kalivas PW. Time course of tyrosine hydroxylase expression after behavioral sensitization to cocaine. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 1993;266:424–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Basile M, Flynn DD, Mash DC. Visualization of dopamine and serotonin transporters in the human brain with the potent cocaine analogue [125I]RTI-55: in vitro binding and autoradiographic characterization. J. Neurochem. 1994a;62:549–556. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Hearn WL, Ruttenber AJ, Wetli CV, Mash DC. High affinity cocaine recognition sites on the dopamine transporter are elevated in fatal cocaine overdose victims. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 1994b;271:1678–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Rothman RB, Rice KC, Partilla J, Mash DC. Kappa2 opioid receptors in limbic areas of the human brain are upregulated by cocaine in fatal overdose victims. Neurosci. 1997;17:8225–8233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Moriwaki A, Wang JB, Uhl GR, Pickel VM. mu-opioid receptors are localized to extrasynaptic plasma membranes of GABAergic neurons and their targets in the rat nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2585–2594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02585.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecott LH, Barchas J, Eberwine J. In situ transcription: Specific synthesis of cDNA in fixed tissue sections. Science. 1988;240:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.2454508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski JQ, Arnold SE. In pursuit of the molecular neuropathology of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;2:274–276. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160024005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanGelder RN, von Zastrow ME, Yool A, Dement WC, Barchas JD, Eberwine JH. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1990;87:1663–1667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Voglestein B, Kinzler KW. Serial analysis of gene expression. Science. 1995;270:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Austin MC, Pierri JN, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 messenger RNA expression in a subset of prefrontal cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:237–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, Vitkun S, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Pappas N, Hitzemann R, Shea CE. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386:827–830. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana SL, Vrana KE, Koves TR, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. Chronic cocaine administration increases CNS tyrosine hydroxylase enzyme activity and mRNA levels and tryptophan hydroxylase enzyme activity levels. J. Neurochem. 1993;61:2262–2268. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Prefrontal function in schizophrenia: confounds and controversies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1996;351:1495–1503. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Kayo T, Lee CK, Prolla TA. Gene expression profiling of aging using DNA microarrays. Mech. Age.Dev. 2002;123:177–193. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney LW, Becker KG, Tresser NJ, Caballero-Ramos CI, Munson PJ, Prabhu VV, Trent JM, McFarland HF, Biddison WE. Analysis of gene expression in mutiple sclerosis lesions using cDNA microarrays. Ann. Neurol. 1999;46:425–428. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<425::aid-ana22>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney LW, Ludwin SK, McFarland HF, Biddison WE. Microarray analysis of gene expression in multiple sclerosis and EAE identifies 5-lipoxygenase as a component of inflammatory lesions. J. Neuroimmuno. 2001;121:40–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Nobrega JN, Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Shannak K, Kish SJ. Amygdala dopamine levels are markedly elevated after self- but not passive-administration of cocaine. Brain Res. 1994;668:39–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito KA, Vickers G, Roberts DCS. Disruption of cocaine and heroin self-administration following kainic acid lesions of the nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1985;23:1029–1036. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]