Abstract

Cocaine/heroin combinations (speedball) exert synergistic neurochemical and behavioral effects that are thought to contribute to the increased abuse potential and subjective effects reported by polydrug users. In vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) was used to examine the effects of chronic intravenous self-administration (25 consecutive sessions) of cocaine (250 μg/inf), heroin (4.95 μg/inf) and speedball (250/4.95 μg/inf cocaine/heroin) on changes in electrically evoked dopamine (DA) efflux, maximal rate of DA uptake (Vmax) and the apparent affinity (Km) of the dopamine transporter (DAT) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). The increase in electrically evoked DA was comparable following cocaine and speedball injection; however, heroin did not increase evoked DA. DAT Km values were similarly elevated following cocaine and speedball, but unaffected by heroin. However, speedball self-administration significantly increased baseline Vmax, while heroin and cocaine did not change baseline Vmax, compared to the baseline Vmax values of drug-naïve animals. Overall, elevated DA clearance is a likely consequence of synergistic elevations of NAc extracellular DA concentrations by chronic speedball self-administration, as reported previously in microdialysis studies. The present results indicate neuroadaptive processes that are unique to cocaine/heroin combinations and cannot be readily explained by simple additivity of changes observed with cocaine and heroin alone.

Keywords: cocaine, dopamine, heroin, speedball, self-administration, voltammetry

INTRODUCTION

Polysubstance abuse remains an issue of rising importance when treating addicts, especially the increasing number of people who co-abuse stimulants and opioids. The combined use of cocaine and opiates, termed “speedball” (Leri et al. 2003), represents a growing subpopulation of drug abusers (Craddock et al. 1997, Greberman & Wada 1994, Kosten et al. 1987). The prevalence of cocaine use among heroin addicts ranges from 30% to 80% (Schutz et al. 1994, Leri et al. 2003). In 2009, the most frequently reported drug combination among European patients entering treatment was heroin and cocaine (Addiction 2009). A controlled clinical study indicated that the co-administration of cocaine and morphine produced subjective effects unique to the combination and distinct from the effects of either drug alone (Foltin & Fischman 1992). Preclinical studies support the concept of pharmacological uniqueness of the combination (Garrido et al. 2007), suggesting that current pharmacotherapeutic treatment approaches for cocaine or heroin abuse may not be as effective for individuals abusing cocaine/heroin combinations. Consequently, a detailed understanding of speedball-induced neurochemical changes in the brain is a prerequisite to discovering effective treatments.

Dopamine (DA) neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) plays an important role in the neuropharmacological effects of drugs of abuse. The manner in which cocaine and opiates impact the mesolimbic DA system is of particular interest, when considering the unique neurochemical profiles reported with speedball combinations. Numerous studies using rodent models of self-administration and experimenter-administered delivery in combination with in vivo microdialysis have shown that speedball induces a synergistic elevation in extracellular DA concentrations ([DA]e) in the NAc compared to cocaine or heroin alone (Hemby et al. 1999, Zernig et al. 1997, Smith et al. 2006). In order to further evaluate the contribution of DAT with regard to the neurochemical effects of speedball administration, in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) can be used to examine DAT reuptake kinetics following drug administration. To this end, analysis of acute speedball effects on DA transmission in the NAc of drug-naïve rats revealed that DAT apparent affinity values were similarly elevated following cocaine and speedball intravenous administration, but unaffected by heroin. Furthermore, neither cocaine, heroin nor speedball induced significant changes in the maximal reuptake rate (Vmax) when administered acutely (Pattison et al. 2011).

Unlike a single injection, chronic cocaine administration, including drug self-administration procedures, significantly affects baseline DA uptake parameters (Oleson et al. 2009). Enhanced DA uptake rate, as measured by Vmax, has been reported in the rat NAc after a history of cocaine exposure (Oleson et al. 2009, Addy et al. 2010) and binge (Mateo et al. 2005) cocaine self-administration. Moreover, the ability of cocaine to inhibit DA uptake, measured by an increase in apparent Km, was severely attenuated following a cocaine binge (Mateo et al. 2005). In contrast, apparent Km was potentiated in the NAc following a cocaine challenge in rats that repeatedly received cocaine injections (15 mg/kg, i.p., seven daily injections) compared to those with only one pre-exposure (Addy et al. 2010). Alterations in DA uptake parameters that take place following chronic speedball administration and how these neuroadaptations influence subsequent acute effects of the drug combination are unknown. In this in vivo voltammetric study, the effects were examined of intravenously injected cocaine, heroin and the speedball combination on evoked DA release and DAT-mediated reuptake parameters in the NAc of rats with a chronic self-administration history.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Male Fisher F-344 rats (n=15; 120–150 days; 270–320 g; Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were housed in acrylic cages in a temperature-controlled vivarium on a 12-hour reversed light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 PM). Rats were group housed before surgery and individually housed after catheterization. Food was restricted to maintain starting body weight and water was available ad libitum, except during experimental sessions that were conducted during the dark phase. All procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80–23) revised in 1996.

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride and heroin hydrochloride were obtained from the Drug Supply Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Pentobarbital and sodium thiopental were purchased from the pharmacy at Wake Forest Baptist Hospital. Sodium heparin was from Elkin-Sinn (Cherry Hill, NJ), methyl atropine nitrate and urethane were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO).

Intravenous Self-Administration

Animals were pretreated with methyl atropine nitrate (10 mg/kg; i.p.) and anesthesia was induced by administration of pentobarbital (40 mg/kg; i.p.). While anesthetized, rats were implanted with chronic indwelling venous catheters as described previously (Hemby et al. 1999, Hemby et al. 1997, Hemby et al. 1996). Briefly, catheters were inserted into the right jugular vein, terminating just outside the right atrium and anchored to muscle near the point of entry into the vein. The distal end of the catheter was guided subcutaneously to exit above the scapulae through a Teflon shoulder harness. The harness provided a point of attachment for a spring leash connected to a single channel swivel at the opposing end. The catheter was threaded through the leash for attachment to a swivel. The fixed end of the swivel was connected to a syringe (for saline and drug delivery) by polyethylene tubing. Infusions of sodium thiopental (150 μl; 15 mg/kg; i.v.) were manually administered as needed to assess catheter patency. Health of the rats was monitored daily by the experimenter and weekly by institutional veterinarians according to the guidelines issued by the Wake Forest University Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institute of Health.

Rats were returned to their home cages and monitored for two to three days before initiating the intravenous (i.v.) drug self-administration procedure. Following surgery, rats received hourly infusions of heparinized 0.9% bacteriostatic saline (1.7 U/ml; 200 μl/hour) using a computer-controlled motor-driven syringe pump in the home cage vivarium. For self-administration sessions, rats were transferred to operant conditioning cages (24.5 × 23.5 × 21 cm) that were enclosed in sound-attenuating chambers and contained a retractable lever positioned 2.5 cm above the floor (requiring approximately 0.25 N to operate), an exhaust fan, an 8 ohm speaker, a tone source, a house light and a red stimulus light directly above the retractable lever. A counterbalanced arm was mounted to the rear corner of the operant chamber onto which the single channel swivel at the end of the rat’s leash was attached. A motor-driven 20 ml syringe pump was attached outside of the sound-attenuating chamber and polyethylene tubing was fed from the drug syringe into the operant chamber through a small hole in the outer chamber.

Rats were assigned randomly into groups to self-administer cocaine (n = 5; 250 μg/inf), heroin (n = 5; 4.95 μg/inf) or speedball (n = 5; 250/4.95 μg/inf cocaine/heroin). Responding was engendered under a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule and the daily session terminated after 15 infusions or 3 hours. Once rats consistently self-administered 15 infusions per session, the schedule was increased to FR2 for 5 training days, followed by 25 consecutive days of 15 infusions per day where stable responding was maintained (as monitored by average inter-infusion intervals within 10%). Under these experimental parameters, rats self-administered 3.75 mg/day of cocaine, 74.25 μg/day of heroin or 3.75 mg/day of cocaine and 74.25 μg/day of heroin (speedball).

In vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV)

Approximately 24 hours after the last self-administration session, rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.2–1.5 g/kg, i.p.) and secured in a stereotaxic frame in a flat skull position. Trephinations were made above the NAc and VTA (AP: +1.3, ML: ±1.3, and AP: −5.2, ML: ±1.0, in mm relative to bregma, respectively). An additional trephination was made in the contralateral hemisphere into which an Ag/AgCl reference electrode was implanted just below the surface of the skull and connected to a voltammetric amplifier. A carbon fiber microelectrode (approximately 80 to 200 μm in length beyond the glass capillary in which it was contained) was secured to the stereotaxic frame arm and connected to the voltage amplifier. The carbon fiber electrode was secured above the NAc trephination and lowered approximately 5 mm below the dura matter and was lowered further by 0.2 mm increments. A bipolar stimulating electrode was connected to a voltage output box, secured above the VTA trephination and lowered approximately 7.5 mm below dura terminating within the medial forebrain bundle. Voltammetric recordings were collected every 100 ms over a 15 second duration by applying a triangular waveform (−0.4 to +1.2 V, 400 V/s). The biphasic stimulation applied by the stimulating electrode consisted of 60 rectangular pulses at 60 Hz, 300 μA and was activated at 5 seconds into each recording. Recorded signals exhibited an oxidation peak at +0.6 V and a reduction peak at − 0.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference), the signature cyclic voltammogram indicative of DA. The average DAT uptake rate (Vmax) was between 1.5 and 2.5 μM/s, indicative of electrode placements in the NAc. The depths of the carbon fiber microelectrode and bipolar stimulating electrode were adjusted from −6.2 to −7.2 and −7.5 to 8.3 mm, respectively, in order to optimize electrically evoked DA release in the NAc.

Once evoked, DA recordings were optimized, stable readings were collected every 5 minutes for at least 50 minutes. When baseline recordings were within 10% of each other for at least 5 measurements, drug (1.0 mg/kg cocaine, 0.03 mg/kg heroin or 1.0/0.03 mg/kg cocaine/heroin) that was previously self-administered was infused through the previously implanted intravenous catheter over a six-second period, immediately followed by an infusion of 0.2 ml of heparinized saline over an additional six seconds. The conclusion of the infusion constituted the beginning of the experiment at time zero. Stimulated recordings were then made at 1, 5 and 10 minutes and thereafter every 10 minutes up to 120 minutes following drug injection.

Carbon fiber microelectrodes were post-calibrated in vitro with known concentrations of DA (2–5 μM). Calibrations were performed in triplicate and the average value for the current at the peak oxidation potential was used to normalize recorded in vivo current signals to DA concentration. The kinetic parameters of DAT (DAT apparent affinity or the Michaelis-Menten constant, Km, and maximal velocity of dopamine reuptake, Vmax) were calculated using LVIT software (UNC, Chapel Hill, NC). DA reuptake by DAT was assumed to follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics and the change in DA concentration ([DA]) during and after stimulated release was fit using the equation:

where f is the stimulation frequency (Hz), and [DA]p is the concentration of DA released per stimulus pulse. Vmax is the Michaelis-Menten parameter for maximal uptake rate of a first-order enzymatic reaction, such as DA reuptake by DAT. Km is defined as the dopamine concentration required for DAT-mediated reuptake rate to reach one half of Vmax. The baseline Km value for DAT was reported previously to be 0.16 μM (Near et al. 1988). The integral form of this equation was used to model the DA response for individual rats at all time points before and after drug injections (Wu et al. 2001). Under the current conditions, there are two substrates competing for DAT binding, which are cocaine and endogenous DA. Therefore, Km is actually apparent Km under this circumstance, but for convenience will be referred to as just Km. A detailed description regarding a model characterizing changes in electrically evoked DA concentrations was provided in previous publications (Wu et al. 2001, Oleson et al. 2009, Wightman et al. 1988, Wightman & Zimmerman 1990).

Data Analysis

One-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to compare effects after acute i.v. drug administration to pre-drug baseline values for evoked DA efflux, DAT apparent affinity (Km), and maximal velocity of dopamine uptake (Vmax) values within each drug group. These data were also analyzed using two-way ANOVA with drug group (cocaine, heroin or speedball) and time as the factors. Evoked DA values were analyzed as a percent of baseline values (baseline defined as the average of five measurements taken at 25, 20, 15, 10 and 5 minutes prior to drug injection). All post hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni t-tests to compare post-drug injection values to baseline (for one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs) and for pairwise comparisons between drugs.

RESULTS

Self-administration

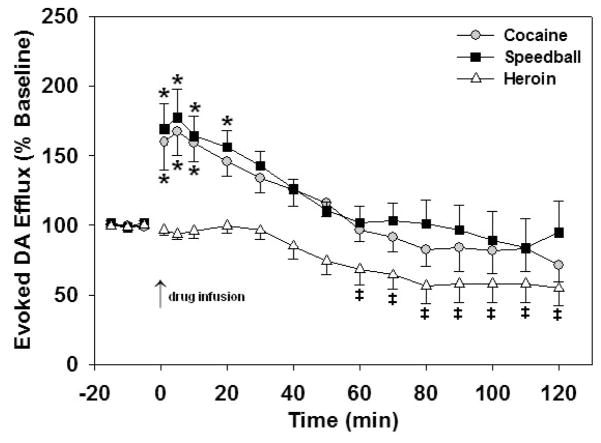

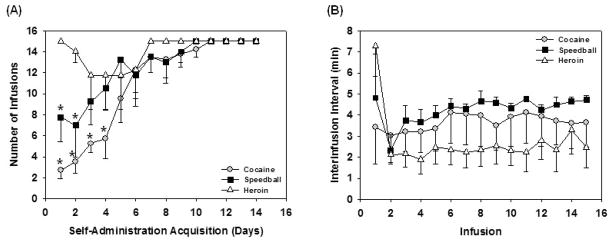

All animals self-administered cocaine (250 μg/infusion), heroin (4.95 μg/infusion) or speedball (250/4.95 μg/infusion cocaine/heroin) under an FR2 for 25 consecutive days. Overall, animals had as close to the same drug self-administration history as possible, and no group had a total number of self-administration days that was significantly more than that of another group. The only slight differences are that heroin self-administering animals required on average three fewer training days under an FR1 and showed faster interinfusion intervals throughout the 25 consecutive days of self-administration under an FR2 (Fig. 1). Those rats self-administering heroin obtained significantly more infusions (P < 0.05) than speedball rats on days 1 and 2, and on days 1 through 4 compared to cocaine rats (Fig. 1a). One-way ANOVA revealed that animals self-administering heroin also showed an overall significantly shorter average interinfusion interval (2.72 ± 0.34 min) as compared to cocaine (3.66 ± 0.092 min) or speedball (4.25 ± 0.17 min) self-administering animals (P < 0.05) over the 25-day period (Fig. 1b). However, these variables do not contribute to the overall amount of drug intake, and enforcing a threshold of 15 infusions per session ensured that speedball animals did not have an overall different amount of cocaine intake than those self-administering cocaine alone, and also did not have an overall difference in heroin intake than those self-administering heroin alone.

Figure 1.

(A) Acquisition of self-administration during the first 14 days of training rats under an FR1 to self-administer cocaine (250 μg/infusion), heroin (4.95 μg/infusion) or speedball (250/4.95 μg/infusion cocaine/heroin). Once rats reached the maximum number of infusions (15) for two days in a row, they began to self-administer under an FR2 for five training days and continued to self-administer for 20 consecutive days thereafter until in vivo FSCV was performed 24 hours following the last self-administration sessions. Data are mean number of infusions for each group (n = 5) ± SEM. Rats trained to self-administer heroin responded for more infusions on days 1 and 2 compared to speedball rats, and on ays 1 through 4 compared to cocaine rats (*P < 0.05). (B) Mean interinfusion invtervals for each group (n = 5) ± SEM throughout daily self-administration sessions over the 25 day period of self-administration under an FR2. Animals self-administering heroin showed an overall significantly shorter average interinfusion interval as compared to cocaine or speedball (P < 0.05) over the 25 day period. However, enforcing a threshold of 15 infusions per session ensured that speedball animals did not have an overall different amount of cocaine intake than those self-administering cocaine alone, and also did not have an overall difference in heroin intake than those self-administering heroin alone.

Electrically evoked DA efflux

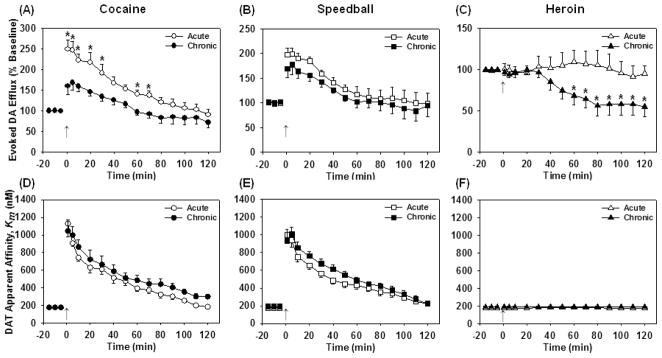

Baseline values of electrically evoked DA efflux, ranging from 0.85–2.20 μM (Fig. 2), were not statistically different between the self-administration groups (P = 0.343). Cocaine, heroin and speedball intravenous infusions significantly altered the levels of electrically evoked DA in the NAc during FSCV (Fig. 3). Cocaine and speedball infusions resulted in significant increases in evoked DA compared to baseline values (P < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference between the cocaine and speedball groups (P = 0.291). Post hoc analyses revealed significant elevations in evoked DA efflux following cocaine administration at 1, 5, 10, and 20 minutes, and at 1, 5, and 10 minutes following speedball administration (P < 0.05). In contrast, heroin administration resulted in a significant decrease in evoked DA efflux compared to baseline (P < 0.001) and compared to cocaine and speedball infusions (P < 0.001). Post hoc analyses identified significant reductions from baseline at 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 minutes after the heroin infusion (P < 0.05). A possible explanation is that heroin-induced decreases in VTA GABAergic cell firing rate (Steffensen et al. 2006) may disinhibit dopaminergic projections to the NAc, resulting in increased basal DA release. An increase in extracellular DA concentration in the absence of DAT inhibition should result in a decrease in electrically evoked DA efflux (Budygin et al. 2001). However, this mechanism is not in agreement with the striking delay of the effect induced by intravenously injected drug. Therefore, the changes in electrically evoked DA efflux at one hour after heroin administration are more likely due to secondary alterations. For example, they could be associated with a higher susceptibility of DA storage to depletion following heroin self-administration.

Figure 2.

DA changes detected by FSCV in the NAc of anesthetized rats following i.v. cocaine, speedball and heroin infusion. Upper panel: Background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms taken from the peak response to the stimulation, which provide chemical information on the analyte. Every signal has an oxidation peak at +0.65 V and reduction peak at −0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl reference, identifying the detected species as DA. Lower panel: Representative concentration-time plots of electrically evoked DA release measured before (solid lines) and 10 min after (dashed lines) drug challenges.

Figure 3.

The influence of chronic self-administration on electrically evoked DA release in NAc following single i.v. challenge infusions of cocaine (1.0 mg/kg), heroin (0.03 mg/kg) and speedball (1.0/0.03 mg/kg cocaine/heroin). Data are expressed as percent of pre-drug baseline DA levels and are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5/group). Baseline values were not significantly different between groups. Cocaine and speedball infusions significantly increased evoked DA levels above baseline levels from 1–20 minutes and 1–10 minutes following drug injection, respectively (*P < 0.05). Heroin administration significantly reduced evoked DA levels below baseline levels from 60–120 minutes following injection (‡P < 0.05). No statistically significant difference in peak DA levels between the cocaine and speedball groups were observed.

DAT apparent affinity (Km)

Cocaine and speedball administration significantly increased DAT apparent affinity (Km), whereas heroin exerted no effect (P < 0.001; Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in apparent Km between cocaine and speedball (P = 1.000) but Km values were found to be significantly lower following heroin infusion compared to speedball or cocaine throughout the experiment (P < 0.001) following drug injections. Post hoc analyses revealed that cocaine induced a significant increase in Km from baseline from 1 to 90 minutes (P < 0.05) and speedball injection resulted in a significant increase in Km from baseline from 1 to 80 minutes (P < 0.05) following drug infusion. Heroin did not alter Km from baseline values (P = 0.994).

Figure 4.

Effects of i.v. challenge infusions of cocaine (1.0 mg/kg), heroin (0.03 mg/kg) and speedball (1.0/0.03 mg/kg cocaine/heroin) on the inhibition of DA uptake, or apparent Km, in NAc following chronic self-administration. Data are expressed as nM concentrations and represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5/group). Baseline values were not significantly different between groups. Cocaine and speedball increased DAT inhibition above baseline levels in a time-dependent manner for 90 and 80 minutes following infusions, respectively (*P < 0.05). As anticipated, heroin did not affect DAT inhibition.

DAT-mediated reuptake rate (Vmax)

No significant differences in Vmax values were observed between baseline and the post-infusion periods within the cocaine, heroin or speedball groups (Fig. 5a). Comparison of baseline Vmax values revealed significant differences between the three groups (P < 0.005). Post hoc analyses revealed elevated baseline Vmax values for the speedball group (2456 ± 336 nM/s) compared to heroin (1440 ± 80 nM/s; P < 0.05), but not cocaine (1802 ± 100 nM/s). Significant differences in Vmax were also observed between groups following drug infusion. Vmax values were significantly greater in the speedball group compared to the cocaine or heroin groups (P < 0.001) and also greater in the cocaine group when compared to heroin (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

(A) Effects of i.v. challenge infusions of cocaine (1.0 mg/kg), heroin (0.03 mg/kg) and speedball (1.0/0.03 mg/kg cocaine/heroin) on maximal velocity of dopamine uptake (Vmax) in NAc following chronic self-administration. The maximal uptake rate is expressed as nM/s and represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5/group). Baseline Vmax values were significantly greater in the speedball group compared to heroin (*P < 0.05). Following drug infusions, Vmax values were significantly increased after speedball administration compared to cocaine and heroin alone (‡P < 0.05). Challenge infusions did not significantly alter Vmax values from baseline values within any of the groups. (B) Effects of chronic self-administration of cocaine (grey bar), speedball (black bar) and heroin (white bar) on Vmax compared to drug-naïve animals (n = 15). Data represent average Vmax values (± SEM) calculated at three time points prior to drug infusions (n = 5/group). The solid and dashed lines (1732 ± 87 nM/s) represent the average ± SEM Vmax for drug-naïve subjects. Chronic self-administration of speedball significantly increased the baseline Vmax value in NAc compared to drug-naïve controls (**P < 0.005). Baseline Vmax values were not significantly different between drug-naïve and self-administering subjects following cocaine or heroin administration.

In order to assess the effect of chronic drug exposure on Vmax, we compared the baseline Vmax values from drug-naïve subjects (Pattison et al. 2011) with values from subjects following chronic self-administration of cocaine, heroin or speedball. The analysis revealed significant increases in baseline Vmax values in subjects with a history of chronic speedball self-administration compared to drug-naïve subjects (P < 0.005; Fig. 5b). Interestingly, no significant differences were observed in baseline Vmax between the drug-naïve and cocaine or heroin self-administering groups.

DISCUSSION

The present study revealed that chronic speedball self-administration resulted in significantly elevated rates of DA reuptake (Vmax) in the NAc compared to cocaine and heroin self-administration. Furthermore, comparison of the present results with the previously published effects following acute speedball, cocaine and heroin administration in drug-naïve subjects (Pattison et al. 2011) revealed significant neuroadaptive responses in DA release and uptake rate, which are attributable to chronic drug self-administration. The most substantial observation between these data sets is that chronic speedball self-administration significantly increased the baseline rate of Vmax compared to drug-naïve subjects. In the present study, a significant increase in the magnitude of electrically evoked DA efflux was observed following both cocaine and speedball injections in animals with a chronic self-administration history. Evoked DA efflux was reduced following chronic self-administration of cocaine, heroin or speedball compared to acute administration of each respective drug in naïve animals (Fig. 6a–c), which may be explained in part by a reduction in VTA DA neuron population activity following repeated drug exposure (Shen et al. 2007).

Figure 6.

Upper Panel: Comparison of electrically evoked DA efflux in NAc of drug-naïve rats (open shapes) and chronically self-administering rats (filled shapes) following a single challenge i.v. infusion of (A) cocaine (1.0 mg/kg), (B) speedball (1.0/0.03 mg/kg cocaine/heroin), and (C) heroin (0.03 mg/kg). Data are expressed as percent of pre-drug baseline DA levels and are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5/group). (A) Cocaine increased the level of evoked DA efflux from baseline in both acute and chronic groups; however, cocaine infusion in the self-administration group resulted in significantly lower levels of evoked DA efflux compared to the acute group (P < 0.001) at 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 and 70 minutes following cocaine challenge (*P < 0.05). (B) Speedball increased the level of evoked peak DA form baseline in both acute and chronic groups, with a significantly greater increase observed in the acute group (P < 0.010). However, post hoc analyses showed that this was an overall difference and not significant at any specific time points. (C) Evoked DA efflux was not significantly altered from baseline following heroin administration in drug-naïve animals; however, chronic heroin self-administration significantly decreased evoked DA compared to the naïve animals (P < 0.001) at 60 to 120 minutes following heroin challenge (*P < 0.05). Lower Panel: Effects of i.v. challenge infusions of (D) cocaine (1.0 mg/kg), (E) speedball (1.0/0.03 mg/kg cocaine/heroin) and (F) heroin (0.03 mg/kg) on the inhibition of DA uptake, or apparent Km, in NAc following chronic self-administration (filled shapes) and in drug-naïve animals (open shapes). Data are expressed as nM concentrations and represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5/group). There were no significant differences in apparent Km between acute and chronic animals within any of the drug groups. (Data of acute administration has been published previously (Pattison et al. 2011) and reprinted with permission.)

In contrast to the differences in evoked DA efflux between acute cocaine and speedball administration (Pattison et al. 2011), no differences were observed between the cocaine and speedball groups following chronic self-administration. The lack of difference may be due to enhanced rate of DA reuptake following speedball self-administration, as has been observed following chronic alcohol and cocaine administration (Budygin et al. 2007, Budygin et al. 2003, Oleson et al. 2009, Mateo et al. 2005). In the present study, baseline Vmax was increased in the speedball group 24 hours following the previous self-administration session. This consequence of chronic speedball self-administration likely contributes to a lack of observed difference in evoked DA efflux between the cocaine and speedball groups in the present study.

The elevated maximal rate of uptake observed in the speedball group is potentially related to the abundance of DATs in the NAc, alterations in membrane polarity, and/or changes in mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and/or protein kinase C signaling cascades (Lin et al. 2003, Moron et al. 2003, Copeland et al. 2005, Zhen et al. 2005). Increases in DAT availability have been observed previously following chronic cocaine self11 administration in rats and non-human primates (Tella et al. 1996, Letchworth et al. 2001), as well as in human post-mortem tissue from cocaine addicts (Little et al. 1993). Elevated DAT activity would serve to decrease [DA]e below baseline levels (Kahlig & Galli 2003) leading to a state of dopaminergic hypofunction during self-administration withdrawal periods. Speedball self-administration may exert similar effects on DAT expression but would be expected to be greater in magnitude given the substantial elevations in [DA]e compared with cocaine alone, as observed in previous studies (Hemby et al. 1999, Zernig et al. 1997, Smith et al. 2006). Further studies are warranted to determine DAT expression in the NAc following speedball self-administration.

Alternatively, the rate of DAT reuptake may be influenced in a DAT density-independent manner. The sodium gradient, which is tightly coupled to membrane potential, is a critical driving force for DA reuptake by the DAT. Increases in Na+/K+ pump activity can increase the rate of DA reuptake. In addition, Na+/K+ ATPase also activates MAP kinase signaling pathways, which appear to be involved in the regulation of DAT transport capacity (Moron et al. 2003). DAT uptake rate is also modulated by both protein kinase A and C signaling pathways (Pristupa et al. 1998). Future studies are necessary to examine the influence of these pathways on the increased rate of DA reuptake kinetics observed in the speedball self-administration group. Particular interest should be paid to examining chronic effects of speedball self-administration on DAT-mediated Vmax, as there appear to be no neuroadaptations apparent in the measure of apparent Km between acute and chronic animals within each drug group (Fig. 6d–f).

Neuroadaptations in DAT function triggered by chronic drug exposure are not necessarily limited to changes in DAT number, but rather to the functional capacity of the rate of uptake (Vmax). Studies report that repeated cocaine administration alters the affinity of DAT (Km) (Budygin 2007, Mateo et al. 2005, Ferris et al. 2011, Addy et al. 2010). For example, the voltammetric analysis of DA uptake parameters in brain slices from rats with binge cocaine self-administration history and withdrawn for one or seven days have shown that Vmax was increased while Km (cocaine-induced inhibition of DAT) was diminished (Mateo et al. 2005). The reduced efficacy of cocaine to inhibit DAT appears to be independent of the ability of DAT to transport DA and other substrates (Ferris et al. 2011). In contrast, administration of cocaine for seven days (i.p., 15 mg/kg) revealed increases in apparent Km of cocaine-exposed animals following one day of withdrawal (Addy et al. 2010). These data suggest a rapid DAT sensitization in the NAc after a short withdrawal period. However, Oleson et al. (2009) did not find significant changes in the efficacy of intravenous cocaine (0.75 mg/kg) to inhibit DAT in rats that exhibited an escalation in the rate of cocaine intake, 24 hours following the final self-administration session. Possible explanations for these discrepancies include differences in experimental preparations (in vitro versus in vivo), dose and route of drug administration, duration of cocaine exposure and withdrawal, presence of drug during testing and differences in the parameters of electrical stimulation. In the present study, the main goal was to compare the effects on accumbal DA kinetics between drug groups (cocaine, heroin and speedball) following chronic (25 days) self-administration and acute (24 hours) withdrawal based on the measures of evoked DA efflux, apparent affinity (Km) and maximal reuptake rate (Vmax), before and after an i.v. drug challenge.

Previous studies have indicated that cocaine-induced increases in electrically evoked DA dynamics as measured by in vivo FSCV are primarily due to DA reuptake inhibition (i.e. increase in the apparent Km) (Budygin 2007, Mateo et al. 2004, Oleson et al. 2009). Given that increases in Km and evoked DA release following drug challenges were indistinguishable between cocaine and speedball groups in the present study, it is likely that changes in the apparent affinity of DAT are not a neuroadaptive response contributing to the observed differences in Vmax. This contention is supported by a previous finding demonstrating that increased inhibition of DAT by chronic cocaine self-administration is not sufficient to modify the apparent Km of DAT for cocaine (Oleson et al. 2009). Additionally, no differences were found in Km values between drug-naïve and self-administration subjects within drug treatment groups over the time course of the experiments. However, since several voltammetric studies have demonstrated a rapid sensitization (Addy et al. 2010) or desensitization of the DAT (Mateo et al. 2005, Ferris et al. 2011) to repeated cocaine administration, additional experiments are needed to further delineate the alterations in Vmax and Km as a function of chronic cocaine and speedball self-administration.

The present study revealed significant differences in DA release and uptake kinetics between cocaine, heroin and speedball following chronic self-administration. Additional efforts utilizing various techniques should be directed toward the significant public health concern of polysubstance abuse. Results from our lab and others have clearly demonstrated that the biochemical and behavioral effects of drug combinations cannot be predicted from individual components alone. The present results in combination with a previous study (Pattison et al. 2011) indicate neuroadaptive processes unique to cocaine/heroin combinations that cannot be readily explained by simple additivity of changes observed with cocaine and heroin alone.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by R01DA012498 (SEH) and K08DA021634 (EAB). All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: all authors had financial support from ABC Company for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LPP, EAB and SEH were responsible for the study concept and design. LPP and SM contributed to the acquisition of animal data. LPP and EAB performed the data analysis. LPP, EAB and SEH interpreted the findings. LPP and SEH drafted the manuscript. LPP, EAB, SEH provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors critically reviewed content and approved the final version for submission.

References

- Addiction, EMCfDaD. Polydrug Use: Patterns and Responses. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Addy NA, Daberkow DP, Ford JN, Garris PA, Wightman RM. Sensitization of rapid dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens core and shell after repeated cocaine in rats. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:922–931. doi: 10.1152/jn.00413.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budygin EA. Dopamine uptake inhibition is positively correlated with cocaine-induced stereotyped behavior. Neurosci Lett. 2007;429:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budygin EA, John CE, Mateo Y, Daunais JB, Friedman DP, Grant KA, Jones SR. Chronic ethanol exposure alters presynaptic dopamine function in the striatum of monkeys: a preliminary study. Synapse. 2003;50:266–268. doi: 10.1002/syn.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budygin EA, Oleson EB, Mathews TA, Lack AK, Diaz MR, McCool BA, Jones SR. Effects of chronic ethanol exposure on dopamine uptake in rat nucleus accumbens and caudate putamen. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0812-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budygin EA, Phillips PEM, Robinson DL, Kennedy AP, Gainetdinov RR, Wightman RM. Effect of acute ethanol on striatal dopamine neurotransmission in ambulatory rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland BJ, Neff NH, Hadjiconstantinou M. Enhanced dopamine uptake in the striatum following repeated restraint stress. Synapse. 2005;57:167–174. doi: 10.1002/syn.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock SG, Rounds-Bryant JL, Flynn PM, Hubbard RL. Characteristics and pretreatment behaviors of clients entering drug abuse treatment: 1969 to 1993. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:43–59. doi: 10.3109/00952999709001686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris MJ, Mateo Y, Roberts DC, Jones SR. Cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporters with intact substrate transport produced by self-administration. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Self-administration of cocaine by humans: choice between smoked and intravenous cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido JM, Marques MP, Silva AM, Macedo TR, Oliveira-Brett AM, Borges F. Spectroscopic and electrochemical studies of cocaine-opioid interactions. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;388:1799–1808. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1375-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greberman SB, Wada K. Social and legal factors related to drug abuse in the United States and Japan. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:731–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Co C, Dworkin SI, Smith JE. Synergistic elevations in nucleus accumbens extracellular dopamine concentrations during self-administration of cocaine/heroin combinations (Speedball) in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Co C, Koves TR, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. Differences in extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens during response-dependent and response-independent cocaine administration in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Martin TJ, Co C, Dworkin SI, Smith JE. The effects of intravenous heroin administration on extracellular nucleus accumbens dopamine concentrations as determined by in vivo microdialysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Smith JE, Dworkin SI. The effects of eticlopride and naltrexone on responding maintained by food, cocaine, heroin and cocaine/heroin combinations in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1247–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig KM, Galli A. Regulation of dopamine transporter function and plasma membrane expression by dopamine, amphetamine, and cocaine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. A 2.5-year follow-up of cocaine use among treated opioid addicts. Have our treatments helped? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:281–284. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800150101012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone P, Pocock D, Wise RA. Morphine-dopamine interaction: ventral tegmental morphine increases nucleus accumbens dopamine release. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39:469–472. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90210-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Bruneau J, Stewart J. Understanding polydrug use: review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction. 2003;98:7–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letchworth SR, Nader MA, Smith HR, Friedman DP, Porrino LJ. Progression of changes in dopamine transporter binding site density as a result of cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2799–2807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02799.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Zhang PW, Zhu X, Melgari JM, Huff R, Spieldoch RL, Uhl GR. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, protein kinase C, and MEK1/2 kinase regulation of dopamine transporters (DAT) require N-terminal DAT phosphoacceptor sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20162–20170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KY, Kirkman JA, Carroll FI, Clark TB, Duncan GE. Cocaine use increases [3H]WIN 35428 binding sites in human striatum. Brain Res. 1993;628:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90932-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo Y, Budygin EA, Morgan D, Roberts DC, Jones SR. Fast onset of dopamine uptake inhibition by intravenous cocaine. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2838–2842. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo Y, Lack CM, Morgan D, Roberts DC, Jones SR. Reduced dopamine terminal function and insensitivity to cocaine following cocaine binge self-administration and deprivation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moron JA, Zakharova I, Ferrer JV, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates dopamine transporter surface expression and dopamine transport capacity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8480–8488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08480.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near JA, Bigelow JC, Wightman RM. Comparison of uptake of dopamine in rat striatal chopped tissue and synaptosomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;245:921–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson EB, Talluri S, Childers SR, Smith JE, Roberts DC, Bonin KD, Budygin EA. Dopamine uptake changes associated with cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1174–1184. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattison LP, Bonin KD, Hemby SE, Budygin EA. Speedball induced changes in electrically stimulated dopamine overflow in rat nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pristupa ZB, McConkey F, Liu F, Man HY, Lee FJ, Wang YT, Niznik HB. Protein kinase-mediated bidirectional trafficking and functional regulation of the human dopamine transporter. Synapse. 1998;30:79–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<79::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz CG, Vlahov D, Anthony JC, Graham NM. Comparison of self-reported injection frequencies for past 30 days and 6 months among intravenous drug users. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, McClenahan AW, Beitner-Johnson D, Terwilliger RZ, Nestler EJ. Biochemical adaptations in the mesolimbic dopamine system in response to heroin self-administration. Synapse. 1995;21:312–318. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen RY, Choong KC, Thompson AC. Long-term reduction in ventral tegmental area dopamine neuron population activity following repeated stimulant or ethanol treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JE, Co C, Coller MD, Hemby SE, Martin TJ. Self-administered heroin and cocaine combinations in the rat: additive reinforcing effects-supra-additive effects on nucleus accumbens extracellular dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:139–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Stobbs SH, Colago EE, Lee RS, Koob GF, Gallegos RA, Henriksen SJ. Contingent and non-contingent effects of heroin on muopioid receptor-containing ventral tegmental area GABA neurons. Exp Neurol. 2006;202:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tella SR, Ladenheim B, Andrews AM, Goldberg SR, Cadet JL. Differential reinforcing effects of cocaine and GBR-12909: biochemical evidence for divergent neuroadaptive changes in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7416–7427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07416.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, Amatore C, Engstrom RC, Hale PD, Kristensen EW, Kuhr WG, May LJ. Real-time characterization of dopamine overflow and uptake in the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1988;25:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman RM, Zimmerman JB. Control of dopamine extracellular concentration in rat striatum by impulse flow and uptake. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1990;15:135–144. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(90)90015-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Reith ME, Wightman RM, Kawagoe KT, Garris PA. Determination of release and uptake parameters from electrically evoked dopamine dynamics measured by real-time voltammetry. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;112:119–133. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernig G, O’Laughlin IA, Fibiger HC. Nicotine and heroin augment cocaine-induced dopamine overflow in nucleus accumbens. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;337:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen J, Chen N, Reith ME. Differences in interactions with the dopamine transporter as revealed by diminishment of Na(+) gradient and membrane potential: dopamine versus other substrates. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]