Abstract

Modelling of the critical micelle concentrations (cmc) using the molecular connectivity indices was performed for a set of 21 cationic gemini surfactants with medium-length spacers. The obtained model contains only the second-order Kier and Hall molecular connectivity index. It is suggested that the index 2 χ includes some information about flexibility. The obtained model was used to predict log10 cmc of other cationic gemini surfactants. The agreement between calculated and experimental values of log10 cmc for the gemini surfactants that were not used in the correlation is very good.

Keywords: Cationic gemini surfactants, QSPR, Critical micelle concentration, Molecular connectivity indices

Introduction

Gemini surfactants are molecules constructed of two hydrophobic chains and two polar/ionic headgroups connected by the various spacer groups. Owing to their structure they have unique properties in aqueous solution, such as low critical micelle concentration (cmc) and high surface activity. The cmc values of these surfactants are significantly lower than those of the corresponding monomeric surfactants and in comparison to their monomeric counterparts, gemini surfactants are more efficient at reducing surface tension. Gemini surfactants demonstrate great potential for gene delivery [1]. Cationic gemini surfactants appear to be excellent for binding and compacting DNA. These surfactants bind DNA with higher efficiency and have better transfection efficiencies than their monomeric counterparts. Many conventional surfactants show good anti-microbial properties with respect to a large spectrum of bacteria, fungi and viruses, and simultaneously they are innocuous for living organisms, but the gemini compounds are much more active [2]. Due to these properties, gemini surfactants have been applied in various areas, such as the drug manufacturing especially in gene therapy, the food industry, cosmetics manufacturing especially in the skin care products, anti-bacterial and the anti-fungal preparations.

One of the main reasons for the current interest in gemini surfactants is their critical micelle concentration values which are lower, by at least one order of magnitude, than those of the corresponding monomeric surfactants. As is well known, the cmc depends on the molecular structure of the surfactants. In general, the cmc in aqueous solution decreases as the hydrophobic character of the surfactant increases. The first relationship between cmc and structure of a molecule was given by Klevens [3] who empirically found that logarithm of cmc linearly decreases with increase in hydrophobic chain length of the surfactant. Gemini surfactants have two alkyl chains and two headgroups, therefore the influence of the variation of these groups on the cmc can be considerable. The important factor which distinguishes gemini surfactants from conventional monomeric surfactants is the connection of the headgroups by the spacer. The nature of the spacer group (length, flexibility, chemical structure) plays an important role in regulating the aggregation properties in the solution [4].

Not long ago, a quantitative structure–property relationship (QSPR) was used for predicting the cmc values of conventional non-ionic [5–8] and ionic [9–12] surfactants. The values of the cmc of gemini surfactants can be significantly changed by a slight modification of the structure of the molecule; therefore modelling and predicting the critical micelle concentration of gemini surfactants directly from the structure of the molecule by the QSPR analysis can be of great interest. Recently, the QSPR study was performed to relate the structure of cationic gemini surfactants to their critical micelle concentration [13]. In this work, the cmc of gemini surfactants was correlated with 12 descriptors (seven topological among them connectivity indices, three statistical, one geometrical and one functional group descriptors).

The previous QSPR models [8, 12] show that critical micelle concentration can be correlated and predicted by using the molecular connectivity indices only. In the present work cationic gemini surfactants are taken into consideration, and just as in the previous papers, in the QSPR study ten indices are used: five connectivity indices and five valence connectivity indices, from zeroth to fourth order in both cases. These indices are calculated from the chemical structure of the molecule and they contain considerable information about the molecule, including the details of electronic structure of each atom and the molecular structure features. The information encoded in molecular connectivity indices has been demonstrated in a variety of examples [14].

As is well known the cmc of the surfactants depends not only on geometrical factors of the molecule but also on other parameters, such as the kind of counterion and electrostatic charge distribution; therefore, just as in the previous paper [12], in order to minimize the influence of factors other than geometrical ones, only cationic gemini surfactants with bromide as counterion were taken into account. Furthermore, among the factors significantly affecting the cmc in aqueous solution are the temperature of the solution and the presence in the solution of added electrolyte and various organic compounds [15]. Therefore all values of cmc taken in the correlation were measured in pure water at room temperature.

Data

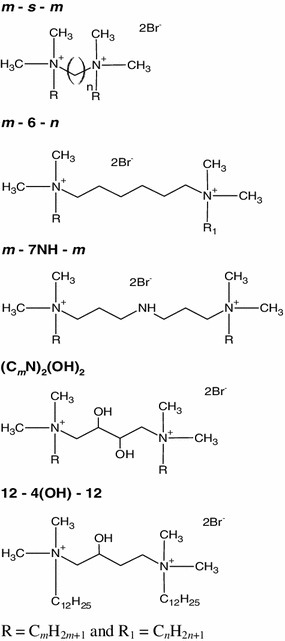

The data set was chosen to contain gemini surfactants with a medium-length spacer. The chemical structures of the surfactants taken into consideration and their abbreviations are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of the surfactants considered and their abbreviations

The cmc of m–s–m gemini surfactants [alkanediyl-α,ω-bis(dimethylalkylammonium bromide)] with a given alkyl chain, particularly for the series with m = 12, increases with the spacer length up to a maximum at four or five methylene units and then decrease with further increase in the number of methylene units in the spacer group [16, 17]. The cmc values of dissymmetric surfactants designated as m–6–6 are about one order of magnitude higher than those of the corresponding m–6–m symmetric surfactants [18] and the cmc decreases as the m/n ratio increases. In the case of the dissymmetric surfactants designated as m–6–n with m + n = 24, the cmc values are comparable with those of the symmetric counterparts with m = 12 [19] and the cmc slightly decreases as the m/n ratio increases. The cmc values of m–7NH–m (1,9-bis(dodecyl)-1,1,9,9-tetramethyl-5-imino-1,9-nonanediammonium dibromide) [20, 21] gemini surfactants are higher than those of the corresponding m–7–m gemini surfactants [20] whereas the cmc values of (CnN)2(OH)2 (1,4-bis(dodecyl-N,N-dimethylammonium bromide)-2,3-butanediol) [22, 23] and 12–4(OH)–12 (1,4-bis(dodecyl-N,N-dimethylammonium bromide)-2-butanol) [23] are lower than those of their hydrophobic spacer homologues. Furthermore, the cmc decreases with increasing hydroxyl substitution in the spacer [23].

Literature data for log10 cmc are given in Table 1. All cmc values were measured at 25.00 °C.

Table 1.

The connectivity indices and the experimental values

| Compound | 0 χ | 1 χ | 2 χ | 3 χ c | 4 χ pc | log10 cmc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8–6–8 | 21.142 | 13.328 | 11.278 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 21.037 | 12.968 | 10.716 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −1.292 |

| 10–6–10 | 23.970 | 15.328 | 12.692 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 23.865 | 14.968 | 12.130 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −2.222 |

| 12–4–12 | 25.385 | 16.328 | 13.399 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 25.279 | 15.968 | 12.837 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −2.932 |

| 12–6–12 | 26.799 | 17.328 | 14.107 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 26.693 | 16.968 | 13.544 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −2.963 |

| 12–7–12 | 27.506 | 17.828 | 14.460 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 27.400 | 17.468 | 13.898 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −3.046 |

| 14–6–14 | 29.627 | 19.328 | 15.521 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 29.522 | 18.968 | 14.958 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −3.824 |

| 16–6–16 | 32.456 | 21.328 | 16.935 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 32.350 | 20.968 | 16.372 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −4.523 |

| 16–7–16 | 33.163 | 21.828 | 17.289 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 33.057 | 21.468 | 16.726 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −4.585 |

| 12–6–6 | 22.556 | 14.328 | 11.985 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 22.451 | 13.968 | 11.423 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −1.790 |

| 14–6–6 | 23.970 | 15.328 | 12.692 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 23.865 | 14.968 | 12.130 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −2.292 |

| 16–6–6 | 25.385 | 16.328 | 13.399 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 25.279 | 15.968 | 12.837 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −2.745 |

| 13–6–11 | 26.799 | 17.328 | 14.107 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 26.693 | 16.968 | 13.544 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −3.009 |

| 14–6–10 | 26.799 | 17.328 | 14.107 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 26.693 | 16.968 | 13.544 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −3.022 |

| 16–6–8 | 26.799 | 17.328 | 14.107 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 26.693 | 16.968 | 13.544 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −3.081 |

| 12–7NH–12 | 27.506 | 17.828 | 14.460 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 27.193 | 17.175 | 13.587 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −2.932 |

| 16–7NH–16 | 33.163 | 21.828 | 17.289 | 2.414 | 2.414 | 32.850 | 21.175 | 16.415 | 2.159 | 2.159 | −4.174 |

| (C10N)2(OH)2 | 24.297 | 15.133 | 13.141 | 2.886 | 3.233 | 23.086 | 14.134 | 11.768 | 2.370 | 2.299 | −2.432 |

| (C12N)2(OH)2 | 27.125 | 17.133 | 14.555 | 2.886 | 3.233 | 25.914 | 16.134 | 13.182 | 2.370 | 2.299 | −3.155 |

| (C14N)2(OH)2 | 29.954 | 19.133 | 15.969 | 2.886 | 3.233 | 28.742 | 18.134 | 14.597 | 2.370 | 2.299 | −4.071 |

| (C16N)2(OH)2 | 32.782 | 21.133 | 17.384 | 2.886 | 3.233 | 31.571 | 20.134 | 16.011 | 2.370 | 2.299 | −4.301 |

| 12–4(OH)–12 | 26.255 | 16.722 | 14.040 | 2.703 | 2.652 | 25.597 | 16.043 | 13.031 | 2.288 | 2.209 | −3.027 |

Methods

Molecular Connectivity Indices (χ) and Valence Molecular Connectivity Indices ()

Molecular connectivity indices, some of the topological descriptors to characterize molecules in structure–property and structure–activity studies, were originally proposed by Randic [24] and later developed and formalized by Kier and Hall [14]. These indices are calculated from the molecular graph, i.e. hydrogen suppressed graphic structural formula of the molecule. The molecular connectivity index is defined as

| 1 |

where m is the order of the connectivity index, k denotes the type of a fragment, which is divided into paths (P), clusters (C), and path/clusters (PC). In formula 1 n m is the number of relevant paths and δ i is the connectivity degree and is equal to the number of atoms to which the i-th atom is bonded. If we replace δ i by , we obtain the valence molecular connectivity index . The expression for the m-th order valence molecular connectivity index is as follows:

| 2 |

where is the valence connectivity degree defined by

| 3 |

where Z ν is the number of valence electrons in the corresponding atom, h is the number of hydrogen atoms connected to the i-th atom and Z is the atomic number.

An example of calculations of molecular connectivity indices for exemplary gemini surfactant and some useful information about the 2 χ index are given in Appendices A and B, respectively.

Correlation Formula

Modelling of the critical micelle concentration as a function of molecular connectivity indices was performed for a diverse set of 21 gemini surfactants. The formula expressing the relationship between the log10 cmc and the molecular connectivity indices was generated using the least-squares method. The statistical calculations were performed using the program STATISTICA 9.1 [25]. In the process of searching the best equation three criteria were taken into account: a correlation coefficient (r), a Fisher ratio value (F) and a standard error (s). The best relationship is that which has possibly highest values of r and F, and simultaneously the lowest value of s.

Results and Discussion

The aim of the present work is to find the simple equation expressing the critical micelle concentration of cationic gemini surfactants as a function of the molecular connectivity indices only. In the process of searching for the simple relationship were used, just as in the previous papers [8, 12], ten indices: five molecular connectivity indices and five valence molecular connectivity indices, from zeroth to fourth order in each case. These indices were calculated for the compounds studied (Fig. 1) using Eqs. 1–3. All values of the connectivity indices and log10 cmc values are listed in Table 1.

Just as in the previous papers we started our correlation procedure with one index. This step is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The values of statistical parameters for the first step

| Indices | 0 χ | 1 χ | 2 χ | 3 χ c | 4 χ pc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 0.979 | 0.973 | 0.981 | 0.201 | 0.210 | 0.967 | 0.959 | 0.972 | 0.201 | 0.208 |

| F | 438.05 | 336.48 | 472.52 | 0.799 | 0.874 | 269.46 | 219.15 | 322.88 | 0.800 | 0.863 |

| s | 0.183 | 0.208 | 0.177 | 0.881 | 0.879 | 0.231 | 0.254 | 0.212 | 0.881 | 0.879 |

We see that the best correlation in this step is for the relationship containing the second-order connectivity index 2 χ, and we get the following formula:

| 4 |

Next to this index we added the remaining indices separately. The values of the correlation coefficients for second step are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The values of correlation coefficients for the second step

| Indices | 0 χ | 1 χ | 2 χ | 3 χ c | 4 χ pc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 0.981 | 0.981 | – | 0.981 | 0.981 | 0.981 | 0.981 | 0.982 | 0.981 | 0.981 |

The addition of other indices in the second step did not change significantly the correlation coefficient and other parameters; therefore at first step the process of searching for the best relationship was ended.

The comparison between the experimental values of log10 cmc with those calculated from Eq. 4 is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of the calculated log10 cmc versus the experimental log10 cmc (r = 0.981, F = 472.52, s = 0.177)

The calculated values of log10 cmc using the obtained model (Eq. 4), along with the experimental values of log10 cmc for the surfactants studied, are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Calculated and literature values of log10 cmc for the studied gemini surfactants

| Compound | Calculated log10 cmc | Experimental log10 cmc |

|---|---|---|

| 8–6–8 | −1.566 | −1.292 |

| 10–6–10 | −2.261 | −2.222 |

| 12–4–12 | −2.608 | −2.932 |

| 12–6–12 | −2.956 | −2.963 |

| 12–7–12 | −3.129 | −3.046 |

| 14–6–14 | −3.650 | −3.824 |

| 16–6–16 | −4.344 | −4.523 |

| 16–7–16 | −4.518 | −4.585 |

| 12–6–6 | −1.914 | −1.790 |

| 14–6–6 | −2.261 | −2.292 |

| 16–6–6 | −2.608 | −2.745 |

| 13–6–11 | −2.956 | −3.009 |

| 14–6–10 | −2.956 | −3.022 |

| 16–6–8 | −2.956 | −3.081 |

| 12–7NH–12 | −3.129 | −2.932 |

| 16–7NH–16 | −4.518 | −4.174 |

| (C10N)2(OH)2 | −2.481 | −2.432 |

| (C12N)2(OH)2 | −3.176 | −3.155 |

| (C14N)2(OH)2 | −3.870 | −4.071 |

| (C16N)2(OH)2 | −4.565 | −4.301 |

| 12–4(OH)–12 | −2.923 | −3.027 |

From Table 4 it follows that the calculated values of log10 cmc are very close to the experimental ones.

Inspection of the data in Tables 1 and 4 reveals that, in agreement with the experiments, as the length of the alkyl chains increase and in consequence the values of index 2 χ increase then the cmc decreases. For example, for the compounds m–6–m with m = 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 we obtain the following values of index 2 χ: 11.278, 12.692, 14.107, 15.521, 16.935 and the following calculated values of cmc: 27.13, 5.49, 1.11, 0.22, 0.05 (mmol·L−1), and the experimental values of cmc are the following: 51, 6, 1.09, 0.15, 0.03 (mmol·L−1) [16, 17, 26], and for the compounds (CmN)2(OH)2 with m = 10, 12, 14, 16 we obtain the following values of index 2 χ: 13.141, 14.555, 15.969, 17.384 and calculated values of cmc: 3.30, 0.67, 0.14, 0.03 (mmol·L−1), and the experimental values of cmc are the following: 3.7, 0.7, 0.085, 0.05 (mmol·L−1) [22], respectively. For the compounds with imino-substituted spacer group, a decrease in the calculated values of cmc with increasing alkyl chain length is also observed. Next, when the number of methylene groups increases in the spacer group and in consequence the values of index 2 χ increase, then the experimental and also the calculated values of cmc decrease. For example, for the compounds 12–s–12 with s = 4, 6, 7 we obtain the following values of index 2 χ: 13.399, 14.107, 14.460 and calculated values of cmc: 2.47, 1.11, 0.74 (mmol·L−1) and the experimental values of cmc are the following: 1.17, 1.09, 0.9 (mmol·L−1) [17, 20], respectively. From Table 4 we can also see that both the experimental and calculated values of cmc decrease with increasing hydroxyl substitution in the spacer and the values of index 2 χ increase also. For example, for the compounds 12–4(OH)n–12 with n = 0, 1, 2 we obtain the following values of index 2 χ: 13.399, 14.04, 14.555 and calculated values of cmc: 2.47, 1.20, 0.67 (mmol·L−1) and the experimental values of cmc are the following: 1.17, 0.94, 0.7 (mmol·L−1) [17, 22, 23], respectively.

If we take into account only the spacer group we can see that for given gemini surfactants the experimental values of cmc decrease with increasing number of methylene groups or hydroxyl substitution in the spacer. For 12–s–12 gemini surfactants, as the spacer increases in length it becomes more flexible [17]. In the case of 12–4(OH)n–12 gemini surfactants, the increase in hydroxyl substitutions in the spacer group may also cause the increase in the flexibility of that group [22]. From the obtained relationship (Eq. 4) it follows that when the number of atoms and/or the number of branches in the spacer group increase, and in consequence the value of 2 χ increases then the cmc decreases. This may suggest that the index 2 χ includes some information about the flexibility of that group.

The obtained model was used to predict log10 cmc for some other cationic gemini surfactants to test Eq. 4; the results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Test of Eq. 4

As shown in Table 5, the agreement between calculated and experimental values of log10 cmc for the cationic gemini surfactants which were not used in the correlation is very good.

The data contained in Tables 4, 5 confirm the conclusion that when the number of branches in the spacer group increases then the critical micelle concentration decreases. For example, for the compounds with six atoms in the spacer group: 12–6–12, 12–5N–12 [21] and (C12N)2(OH)2, we obtain the following values of index 2 χ: 14.107, 14.375, 14.555, the following calculated values of cmc: 1.11, 0.82, 0.67 (mmol·L−1), and the experimental values of cmc are the following: 1.09, 0.97, 0.7 (mmol·L−1) [17, 21, 22], respectively.

Conclusion

From the obtained relationship, it follows that when the number of atoms and/or the number of branches increase in the spacer group then the cmc decreases. This refers not only to the spacer group but also to the whole molecule and is in agreement with some experimental and also theoretical results obtained for conventional surfactants [10, 15]. The increase in the number of atoms or branches influences the flexibility and consequently micelle formation. This suggests that the 2 χ index, appearing in the model, includes some information about flexibility.

The results obtained for the compounds taken into consideration (Tables 4, 5) show that the obtained model, which contains only the Kier and Hall index of second-order, can be used to predict the cmc of cationic gemini surfactants especially bis-quaternary ammonium bromide salts with medium-length spacers and can be helpful in designing novel cationic gemini surfactants.

Appendix A

Example of Calculations of the Indices

This section illustrates the calculations of molecular connectivity and valence molecular connectivity indices for the 8–6–8 gemini surfactant. These indices are calculated from the molecular graph in which vertices represent atoms and edges symbolize covalent bonds. The molecular structure and the corresponding molecular graph of the compound are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The molecular structure and the molecular graph of 8–6–8 gemini surfactant

The numbers 1–28 are the labels of the atoms in the graph. The corresponding values of connectivity degree are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

The values of and

| Labels of atoms | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| δ ν | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

The calculations of connectivity indices (from zeroth to fourth order) and valence connectivity indices (from zeroth to fourth order) are the following:

and

Appendix B

Information About the 2χ Index

The second order connectivity index 2 χ appearing in the obtained model does not differentiate heteroatoms, it includes information about three-atom fragments and its values depend on the isomers of the compound, the values of 2 χ increase with increased branching in the molecule [14]. The dependence of the values of index 2 χ on the isomers of pentane is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The molecular graphs of the isomers of pentane and corresponding values of index 2 χ

The molecular graphs of the isomers of pentane are ranked according to the increasing values of index 2 χ. We can see that the increase in branching in the molecule results in the increase the values of index 2 χ. It is also evident that when the number of atoms increases in the molecule then 2 χ also increases. But if the increase the number of atoms in the molecule is related to increasing of branches, then the increase in 2 χ is larger. The influence of the number of atoms in the molecule on the values of index 2 χ is presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The comparison of values of index 2 χ for the molecular graphs with different number of atoms

References

- 1.Kirby AJ, Camilleri P, Engberts JBFN, Feiters MC, Nolte RJM, Soderman O, Bergsma M, Bell PC, Fielden ML, Rodriguez CLG, Guedat P, Kremer A, McGregor C, Perrin C, Ronsin G, Ejik MCP. Gemini surfactants: new synthetic vectors for gene transfection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1448–1457. doi: 10.1002/anie.200201597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shukla D, Tyagi VK. Cationic gemini surfactants: a review. J. Oleo Sci. 2006;55:381–390. doi: 10.5650/jos.55.381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klevens HB. Structure and aggregation in dilute solutions of surface active agents. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1953;30:74–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02635002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zana R. Dimeric (gemini) surfactants: effect of the spacer group on the association behavior in aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002;248:203–220. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2001.8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huibers PDT, Lobanov VS, Katritzky AR, Shah DO, Karelson M. Prediction of critical micelle concentration using a quantitative structure–property relationship approach. 1. Nonionic surfactants. Langmuir. 1996;12:1462–1470. doi: 10.1021/la950581j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Li G, Zang X, Wang R, Lou A. A quantitative structure–property relationship study for the prediction of critical micelle concentration of nonionic surfactants. Colloids Surf. A. 2002;197:37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7757(01)00812-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan S, Cai Z, Xu G, Jiang Y. Quantitative structure–property relationship of surfactants: prediction of critical micelle concentration of nonionic surfactants. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2002;280:630–636. doi: 10.1007/s00396-002-0659-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mozrzymas A, Różycka-Roszak B. Prediction of critical micelle concentration of non-ionic surfactants by a quantitative structure–property relationship. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2010;13:39–40. doi: 10.2174/138620710790218195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huibers PDT, Lobanov VS, Katricky AR, Shah DO, Karelson M. Prediction of critical micelle concentration using a quantitative structure–property relationship approach. 2. Anionic surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997;187:113–120. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1996.4680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jalali-Heravi M, Konouz E. Prediction of critical micelle concentration of some anionic surfactants using multiple regression techniques: a quantitative structure–property relationship study. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2000;3:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s11743-000-0112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jalali-Heravi M, Konouz E. Multiple linear regression modelling of the critical micelle concentration of alkyltrimethylammonium and alkylpyridinium salts. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2003;6:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s11743-003-0244-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mozrzymas A, Różycka-Roszak B. Prediction of critical micelle concentration of cationic surfactants using connectivity indices. J. Math. Chem. 2011;49:276–289. doi: 10.1007/s10910-010-9738-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kardanpour Z, Hemmateenejad B, Khayamian T. Wavelet neutral network-based QSPR for prediction of critical micelle concentration of gemini surfactants. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2005;531:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kier LB, Hall LH. Molecular Connectivity in Structure–Activity Analysis. Letchworth: Research Studies Press Ltd; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen MJ. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junior PBS, Tiera VAO, Tiera MJ. A fluorescence probe study of gemini surfactants in aqueous solution: a comparison between n–2–n and n–6–n series of the alkanediyl-a,w-bis(dimethylalkylammonium bromides) Eclet. Quim. 2007;32:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wettig SD, Verrall RE. Thermodynamic studies of aqueous m–s–m gemini surfactant systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;235:310–316. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.7348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan Y, Li Y, Cao M, Wang J, Wang Y, Thomas RK. Micellization of dissymmetric cationic gemini surfactants and their interaction with dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Langmuir. 2007;23:11458–11464. doi: 10.1021/la701493s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Wang J, Wang Y, Ye J, Yan H, Thomas RK. Micellization of a series of dissymmetric gemini surfactants in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:11428–11432. doi: 10.1021/jp035198z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbar J, Tavakoli N, Marangoni DG, Wettig SD. Mixed aggregate formation in gemini surfactant 1,2-dialkyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;377:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wettig SW, Wang C, Verrall RE, Foldvari M. Thermodynamic and aggregation properties of aza- and imino-substituted gemini surfactants designed for gene delivery. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007;9:871–877. doi: 10.1039/b613269c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen MJ, Liu L. Surface activity and premicellar aggregation of some novel diquaternary gemini surfactants. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996;73:885–890. doi: 10.1007/BF02517990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wettig SD, Nowak P, Verrall RE. Thermodynamic and aggregation properties of gemini surfactants with hydroxyl substituted spacers in aqueous solution. Langmuir. 2002;18:5354–5359. doi: 10.1021/la011782s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randic M. On characterization of molecular branching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:6609–6615. doi: 10.1021/ja00856a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 9.1. www.statsoft.com. StatSoft, Inc. (2010)

- 26.Ali MS, Suhail M, Ghosh G, Kamil M, Kabir-ud-Din Interactions between cationic gemini/conventional surfactants with polyvinylpyrrolidone: specific conductivity and dynamic light scattering studies. Colloids Surf. A. 2009;350:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu T, Lan Y, Liu Ch, Huang J, Wang Y. Surface properties, aggregation behavior and micellization thermodynamics of a class of gemini surfactants with ethyl ammonium headgroups. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;377:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu LG, Xie AJ, Shen YH. Synthesis and surface activity of novel triazole-based cationic gemini surfactants. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2003;14:653–656. [Google Scholar]