Abstract

The heterotetrameric AP-1 complex is involved in the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles at the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and interacts with sorting signals in the cytoplasmic tails of cargo molecules. Targeted disruption of the mouse µ1A-adaptin gene causes embryonic lethality at day 13.5. In cells deficient in µ1A-adaptin the remaining AP-1 adaptins do not bind to the TGN. Polarized epithelial cells are the only cells of µ1A-adaptin-deficient embryos that show γ-adaptin binding to membranes, indicating the formation of an epithelial specific AP-1B complex and demonstrating the absence of additional µ1A homologs. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors are cargo molecules that exit the TGN via AP-1–clathrin-coated vesicles. The steady-state distribution of the mannose 6-phosphate receptors MPR46 and MPR300 in µ1A-deficient cells is shifted to endosomes at the expense of the TGN. MPR46 fails to recycle back from the endosome to the TGN, indicating that AP-1 is required for retrograde endosome to TGN transport of the receptor.

Keywords: AP-1/clathrin/mannose 6-phosphate receptor/mouse

Introduction

In the trans-Golgi network (TGN) proteins are sorted to multiple intracellular and extracellular destinations. Sorting of transmembrane proteins involves the binding of cytosolic proteins to sequences within their cyto plasmic domains. These cytosolic proteins participate in the formation of a coat at the site of transport vesicle formation. Assembly of the coat structures is required for budding of the transport vesicle (Matter and Mellman, 1994; Schmid, 1997; Hirst and Robinson, 1998; Allan and Balch, 1999; Heilker et al., 1999).

Clathrin forms coats together with the heterotetrameric adaptor protein complexes AP-1 and AP-2 at the TGN and the plasma membrane. The AP-1-containing clathrin coats are predominantly found at the TGN, where their function is seen in mediating TGN to endosome transport (Heilker et al., 1999). Recently, AP-1 has also been detected on transferrin receptor-containing tubular endosomes in MDCK cells, where its function is seen in transporting the transferrin receptor from apical to basolateral endosomes (Futter et al., 1998). AP-2 is found in clathrin coats at the plasma membrane. The AP-3 and AP-4 complexes are homologous to AP-1 and AP-2, but it is not clear whether they mediate clathrin coat formation as well (Heilker et al., 1999; Hirst et al., 1999).

The ubiquitously expressed AP-1 consists of two 100 kDa adaptins, γ and β1, the 47 kDa adaptin µ1A and the 19 kDa adaptin σ1. γ- and β1-adaptin interact with clathrin, but only β1-adaptin is able to induce clathrin cage formation in vitro. γ-adaptin increases the efficiency of β1-induced clathrin cage formation (Schmid, 1997). γ-adaptin governs AP-1 complex formation, thus preventing degradation of β1-, µ1A- and σ1-adaptins (Zizioli et al., 1999). A chimera of 311 N-terminal amino acids of γ-adaptin and of α-adaptin, its homolog in the AP-2 complex, recruits µ1A and σ1 into a hybrid complex of γ/α, µ1A, σ1 and β2. This complex binds to the TGN, demonstrating that β1-adaptin is not required for binding of AP-1 to the TGN (Page and Robinson, 1995). Nothing is known about the function of σ1-adaptin.

The µ- and β-adaptins of the adaptor complexes appear to function in the recruitment of cargo molecules into the transport vesicles. Sequences have been identified in the cytoplasmic tails of cargo proteins, which determine the sorting of the cargo. Many of these sequences contain either a critical tyrosine or a leucine flanked by a second leucine or an isoleucine, valine, alanine or methionine. The µ- and β-adaptins interact with the tyrosine- and the leucine-based sorting signals (Bonifacino and Dell’Angelica, 1999; Heilker et al., 1999). The residues required for binding of tyrosine-based signal sequences by µ2 are conserved between the different members of the µ-adaptin family (Bonifacino and Dell’Angelica, 1999). Among the cargo molecules of AP-1-containing clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) are the mannose 6-phosphate receptors MPR46 and MPR300, the lysosomal membrane protein LAMP-1, the invariant chain of the MHC class II receptor, the CD3γ subunit of the TCRαβ/CD3 receptor complex, furin and the varicella–zoster virus glycoprotein I (Glickman et al., 1989; Mathews et al., 1992; Méresse and Hoflack, 1993; Alconada et al., 1996; Höning et al., 1996, 1997; Dietrich et al., 1997; Dittié et al., 1997).

We mutated the µ1A-adaptin gene of AP-1 in mice to study its role in AP-1 function. Homozygosity for the mutant allele is embryonic lethal. µ1A-deficient cells lack γ-adaptin and clathrin binding to the TGN. µ1A-deficient fibroblasts mislocalize the two MPRs to endosomes and missort lysosomal enzymes into the secretions. Impaired endosome to TGN trafficking, as shown for one of the two MPRs, points to an important role of AP-1 in endosome function.

Results

µ1A-adaptin gene Adtm1A: isolation, genomic locus and targeted mutation

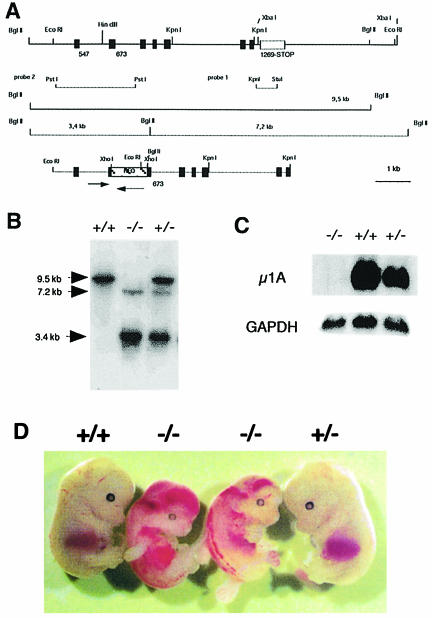

Mouse µ1A-adaptin cDNA cloned from mouse total kidney RNA by RT–PCR was used to screen a mouse chromosomal DNA library. Four library clones were isolated, which contained identical chromosomal DNA fragments. A 9.5 kb EcoRI fragment was subcloned from a library clone, which contains eight exons encoding amino acids 132–423 of µ1A (Figure 1A). An MspI restriction enzyme polymorphism between the µ1A-adaptin gene Adtm1A of Mus musculus and Mus spretus was used to map the genomic locus of Adtm1A. In M.musculus a 6 kb and in M.spretus a 4 kb fragment hybridized with µ1A-adaptin cDNA. Adtm1A was mapped to chromosome 8 at 37 cM between the markers Ncan and D8Wsu38e (data available at the Jackson Laboratory database). No Adtm1A homolog nor a pseudogene was found. The neoR gene was introduced into a XhoI site in exon n + 1 and the 5.6 kb EcoRI–KpnI fragment was electroporated into the embryonic stem cell line ES 14-1 (Figure 1A). Five colonies out of 25 tested carried a homologous recombination event. ES cells carrying the targeted Adtm1A allele were injected into day 3.5 p.c. blastocysts (donor C57/Bl6) and three male chimeras were obtained. Two of these had germline transmissions of the targeted Adtm1A allele.

Fig. 1. Targeted disruption of the µ1A-adaptin gene. (A) Genomic 9.5 kb EcoRI µ1A locus (top) and 5.6 kb EcoRI–KpnI targeting construct (bottom). Exons are indicated by black bars. Arrows indicate µ1A and neoR ORF. Lines mark chromosomal DNA fragments generated by BglII digest in control and mutant cells used to demonstrate homologous recombination and the DNA fragments used as internal (probe 1) and external (probe 2) probes for hybridization of BglII-digested chromosomal DNA. (B) Southern blot analysis of BglII-digested chromosomal DNA isolated from amnion epithelia of day 12.5 p.c. embryos hybridized with probe 2. (C) Northern blot of total embryonic fibroblast RNA hybridized first with 32P-labeled mouse µ1A cDNA and then with GAPDH cDNA. (D) Embryos from a litter isolated at day 13.5 of embryonic development.

No µ1A-deficient animals were born after crossing +/– animals, indicating embryonic lethality of µ1A-deficient mice. Pregnant animals were killed and the embryos genotyped (Figure 1B) to analyze up to which embryonic stage µ1A-deficient embryos develop. µ1A-deficient embryos die around day 13.5 (Figure 1D). At day 16.5 necrotic embryos were detected. Genotyping of embryos at day 13.5 and younger revealed a Mendelian inheritance of the targeted Adtm1A locus (not shown). µ1A-deficient embryos show hemorrhages into the ventricles and the spinal canal (Figure 1D), beginning as early as day 10.5 of gestation. Embryonic fibroblast cell lines were established from day 11.5 embryos. They lack µ1A mRNA (Figure 1C) and µ1A-adaptin (see below).

AP-1 complex formation in µ1A-deficient cells

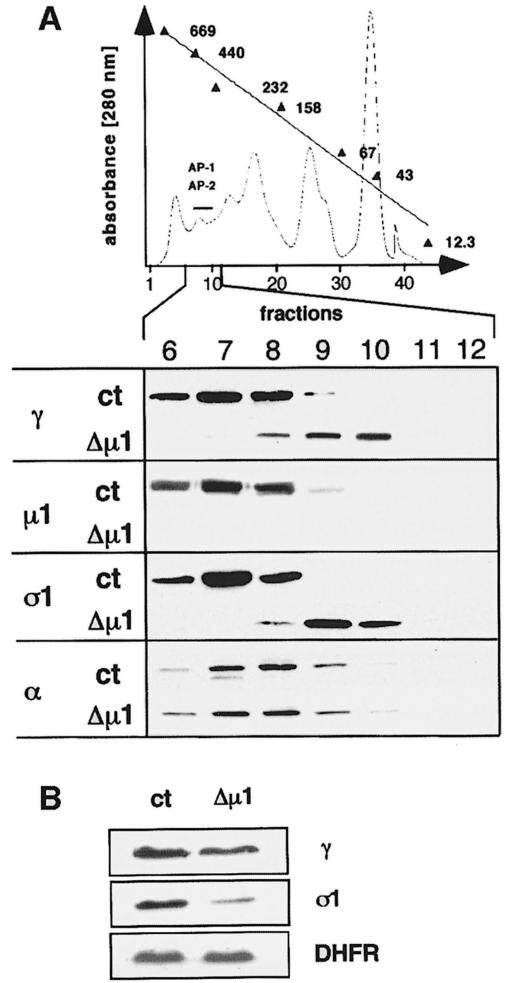

AP-1 complex assembly was analyzed by size fractionation of cytosol isolated from embryonic fibroblast cell lines (Figure 2A). Heterotetrameric AP-1 and AP-2 complexes from control cells were detected in fractions 6–9 using anti-γ, anti-µ1A, anti-σ1 and anti-α antibodies. The mean apparent molecular mass of AP-1 and AP-2 was 400 kDa (Zizioli et al., 1999).

Fig. 2. AP-1 adaptins in µ1A-deficient cells. (A) AP-1 complex assembly. Shown is a gel-filtration profile of a µ1A-deficient cytosol prepared from embryonic fibroblasts. Fractions containing adaptor complexes AP-1 and AP-2 are indicated by a bar. Numbers are kilodaltons of marker proteins used for calibration (see Materials and methods). Western blot analysis of fractions 6–12 of control (ct) and µ1A-deficient cytosols. AP-2 distribution detected with an anti-α-adaptin antibody served as a control for the adaptor fractionation by gel filtration. (B) γ- and σ1-adaptin in cell extracts of control (ct) and µ1A-deficient cells analyzed by Western blotting. Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) was used as control. γ-adaptin is reduced to 70% and σ1-adaptin to 30% of control.

The γ- and σ1-adaptin subunits of µ1A-deficient cytosol eluted in fractions 8–10 with a mean apparent mol. wt of 340 kDa. The apparent size of the α-adaptin-containing AP-2 complex was not affected in the µ1A-deficient cells. µ1A-adaptin was not detectable nor free γ-, β- or σ1-adaptins. This suggests that the remaining AP-1 subunits exist as complexes. The mean mol. wt of 340 kDa is compatible with the calculated molecular weight of a heterotrimeric complex of γ, β1 and σ1. Quantitative Western blots, however, indicated that in µ1A-deficient cells γ- and σ1-adaptin are present in non-stoichiometric amounts. γ-adaptin levels are reduced to 70% of control and σ1-adaptin to 30% of control (Figure 2B). This implies that only a fraction of γ-adaptin can be part of a heterotrimeric complex and that the remaining γ-adaptin may be part of homo-oligomers or be complexed with other compounds. Moreover, the reduction of steady-state concentrations of γ- and σ1-adaptins points to a reduced stability of free adaptins or a regulation of their expression (Zizioli et al., 1999). As mRNA levels of γ- and σ1-adaptins are not altered in µ1A-deficient cells (not shown), regulation of expression would be by a translational control mechanism.

Localization of γ-adaptin in µ1A-deficient cells

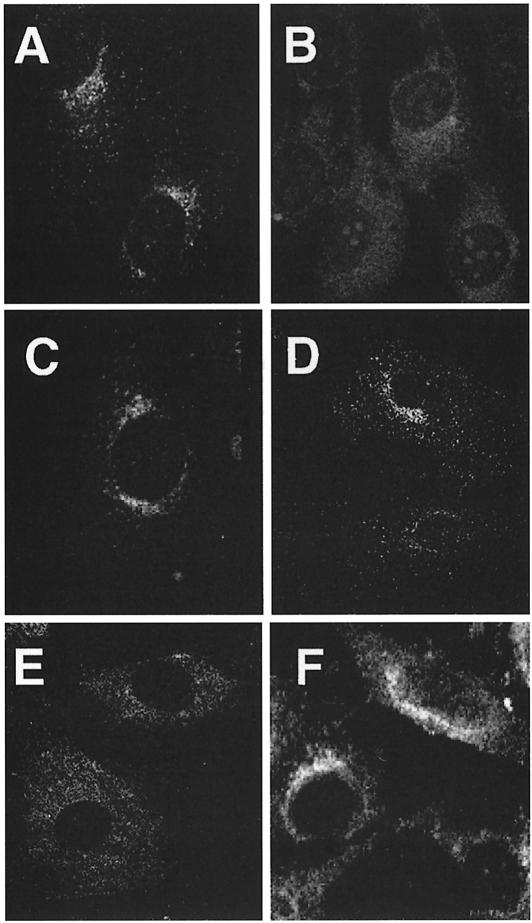

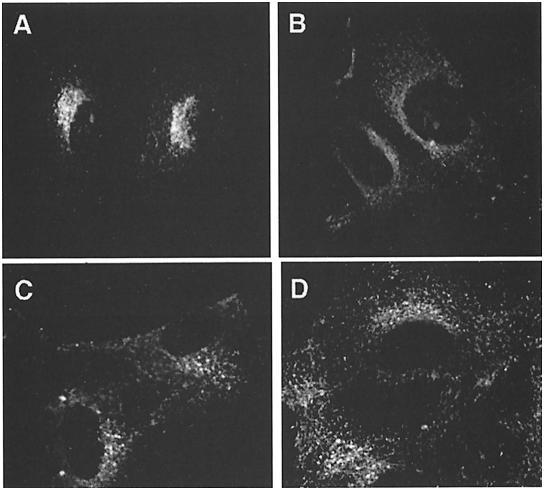

Staining of control cells with anti-γ-adaptin revealed labeling of perinuclear structures, which is assumed to reflect AP-1 bound to the TGN, and of cytoplasmic vesicles, presumably corresponding to AP-1 bound to endosomes (Figure 3A). Exposure of cells to brefeldin A for 1 min led to the complete disappearance of membrane staining (not shown). This is in accordance with the known effects of brefeldin A, which prevents binding of AP-1 to membranes and redistributes AP-1 into the cytoplasm (Robinson and Kreis, 1992; Wong and Brodsky, 1992). Staining of µ1A-deficient cells for AP-1 complexes did not show any membrane labeling and revealed the diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence similar to that seen in control cells treated with brefeldin A (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. Localization of AP-1 and clathrin in embryonic fibroblasts. AP-1 was detected with anti-γ-adaptin antibodies (A, B and C) and clathrin with anti-chc antibodies (D, E and F). (A and D) Control; (B and E) µ1A-deficient cells; (C and F) µ1A-deficient cells with ectopic expression of µ1A.

Staining for clathrin shows in control cells a perinuclear concentration of punctate structures, which reflect CCVs at the TGN, and punctate structures throughout the cell, which are considered to represent mostly clathrin-coated pits at the cell surface (Figure 3D). In µ1A-deficient cells clathrin at the TGN was not detectable (Figure 3E), indicating that binding of clathrin to the TGN requires AP-1 and that the remaining AP-1 adaptins or other adaptor complexes cannot substitute for AP-1 in the formation of CCVs at the TGN. Clathrin-coated pits or CCVs at the TGN were also not detectable in electron microscopic images.

Binding of AP-1 to the TGN of µ1A-deficient cells

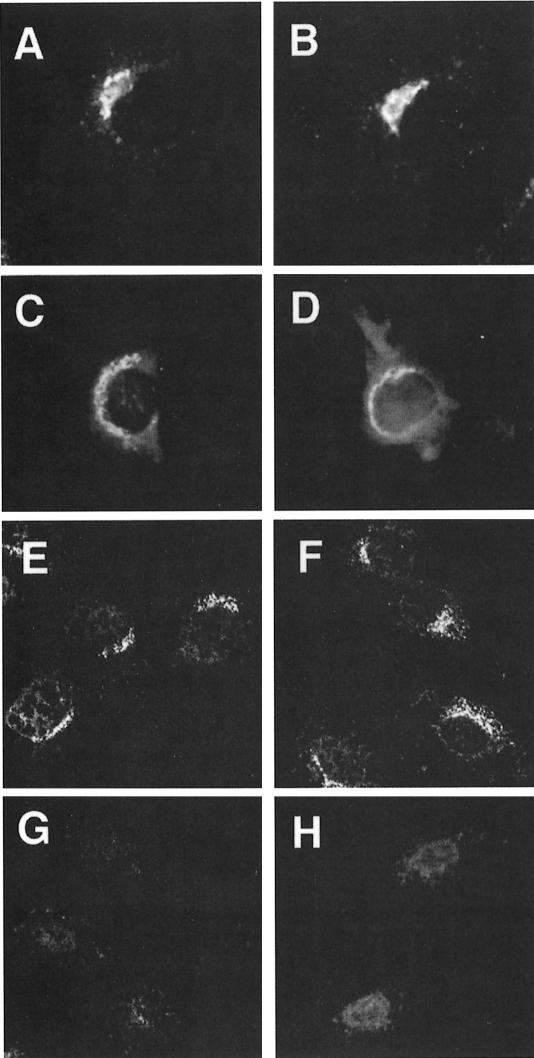

The morphological appearance of the Golgi apparatus in µ1A-deficient cells was examined by labeling with the fluorescent BODIPY FL C5 ceramide, whose accumulation in the Golgi (Pagano et al., 1991) requires metabolism (Martin and Pagano, 1994; Putz and Schwarzmann, 1995), and by immunolocalization of the TGN marker TGN38. Both markers showed a normal appearance of the Golgi (Figure 4A–D),which is in agreement with in vitro data demonstrating interaction of its cytoplasmic tail with µ2, but not with µ1A (Stephens et al., 1997). Also electron microscopic images did not indicate morphological alterations of the TGN.

Fig. 4. Binding of AP-1 to the TGN. (A–D) Staining of the Golgi with BODIPY FL C5-ceramide in control (A) and µ1A-deficient cells (B) and by the TGN marker TGN38 (epifluorescence) by indirect immunofluorescence analysis in control (C) and µ1A-deficient fibroblasts (D). (E–H) Binding of AP-1 to the TGN of control (E and H) and µ1A-deficient cells (F and G) permeabilized with digitonin. Bound AP-1 was detected with an anti-γ-adaptin antibody (confocal images). Permeabilized cells were incubated with GTPγS-supplemented cytosol from control (E, F and G) or µ1A-deficient (H) cells. In (G) brefeldin A was present during the binding.

To test the ability of the TGN in µ1A-deficient cells to bind AP-1, control and µ1A-deficient cells were permeabilized with digitonin and incubated in the presence of GTPγS with AP-1-containing cytosol prepared from control cells (Robinson and Kreis, 1992). AP-1 bound to the TGN of control and µ1A-deficient cells (Figure 4E, F), and binding was sensitive to brefeldin A (shown for µ1A-deficient cells in Figure 4G). The experiment was repeated with cytosol from µ1A-deficient cells that had been concentrated to contain similar amounts of σ1-adaptin as cytosol from control cells. No binding of γ-adaptin to the TGN in either control or µ1A-deficient cells was detectable (shown for control cells in Figure 4H). These data indicate that deficiency of µ1A does not affect the innate ability of the TGN to bind AP-1 and that the remaining AP-1 adaptins, although forming complexes, are unable to bind to the TGN.

AP-1 function in µ1A-deficient epithelial cells

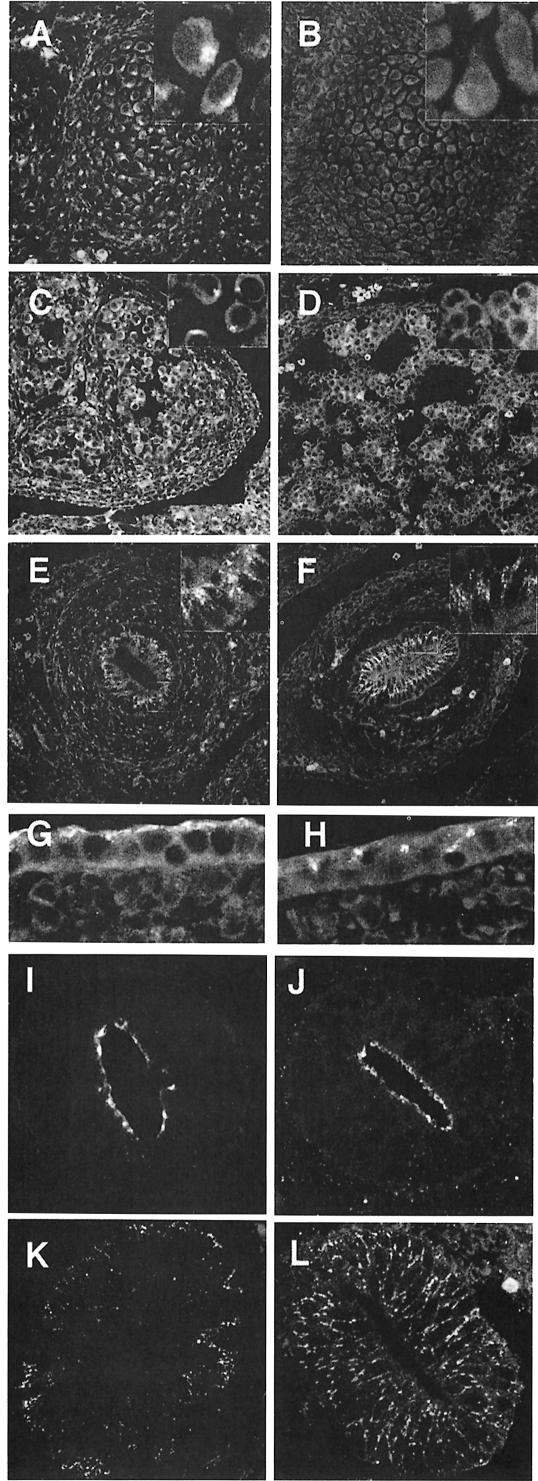

µ1A-adaptin-deficient embryos develop until mid-organogenesis, while γ-adaptin deficiency causes death prior to implantation (Zizioli et al., 1999). This points to the existence of a tissue-specific µ1A homolog able to interact with the ubiquitously expressed γ-adaptin. An epithelial specific µ1B-adaptin has been identified, which is expressed in all polarized epithelial cells of mouse embryos and mice (Ohno et al., 1999). We analyzed the µ1A-deficient embryos for cells containing membrane-bound γ-adaptin, indicating the presence of functional µ1A homolog. Cryosections of control and µ1A-deficient embryos were stained with anti-γ-adaptin antibodies and analyzed by confocal microscopy. In control embryos all cells showed membrane binding of γ-adaptin, which appeared more intense in polarized epithelial cells. In µ1A-deficient embryos polarized epithelial cells, e.g. of the primitive gut, kidneys and epidermis, showed residual γ-adaptin staining of membranes (Figure 5E–H). These cells are known to express µ1B, suggesting that µ1B interacts with the ubiquitously expressed γ-adaptin, forming a functional AP-1B complex. All other cell types of the µ1A-deficient embryos were devoid of γ-adaptin membrane binding, as shown in Figure 5 for vertebral bodies and the embryonic liver, demonstrating the absence of additional cell type-specific µ1A-adaptin isoforms. Absence of µ1A-adaptin expression in embryos did not impair the condensation of cells and the formation of various organ anlagen. However, the embryos appeared soft and tissue preservation during the fixation procedure for cryosectioning was difficult, as can be seen in the liver (Figure 5D). We did not observe morphological alterations in paraffin sections of the embryos.

Fig. 5. Labeling of cryosections of the embryos for γ-adaptin staining. Shown are vertebral bodies of control (A) and µ1A-deficient (B) embryos, liver of control (C) and µ1A-deficient (D) embryos, the gut of control (E) and µ1A-deficient (F) embryos, and epidermis of ct (G) and µ1A-deficient (H) embryos. Polarization of gut epithelial cells demonstrated by staining for tight junctions with anti-ZO-1 in ct (I) and µ1A-deficient cells (J) and for the LDL receptor by fluorescent LDL in ct (K) and µ1A-deficient cells (L).

The µ1B-deficient cell line LLC-PK1 does not grow as a confluent monolayer in culture and missorts the LDL receptor to the apical plasma membrane. Ectopic expression of µ1B restores basolateral sorting of the LDL receptor as well as formation of a confluent monolayer. We tested gut epithelial cells of µ1A-deficient embryos for the formation of tight junctions by ZO-1 immunofluorescence and for basolateral sorting of the LDL receptor by labeling the cells with fluorescent LDL. ZO-1 is localized to the apical surface in control and µ1A-deficient cells, and the LDL receptor is excluded from this area and found exclusively on the basolateral plasma membrane in control as well as µ1A-deficient cells (Figure 5I–L).

Distribution of cargo molecules transported by AP-1-containing CCVs

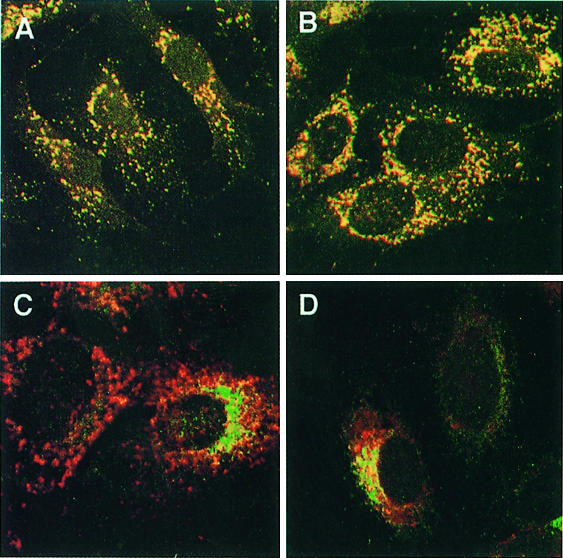

The lysosomal membrane glycoprotein LAMP-1 and the two mannose 6-phosphate receptors MPR46 and MPR300 are known to exit the TGN via AP-1-containing CCVs (Hille-Rehfeld, 1995; Höning et al., 1996). LAMP-1 co-localized with cathepsin D and β-glucuronidase in double-immunofluorescence analysis, demonstrating its localization to lysosomes (Figure 6A and B). We monitored missorting of LAMP-1 to the plasma membrane in AP-1-deficient cells by endocytosis of anti-LAMP-1 antibody during an incubation time of 2 h at 37°C and detection of internalized antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 6C and D). AP-3-deficient fibroblasts revealed transport of LAMP-1 to lysosomes via the cell surface by rapid internalization of anti-LAMP-1 antibodies (Kantheti et al., 1998; Le Borgne et al., 1998; Dell’Angelica et al., 1999). No anti-LAMP-1 antibody uptake was observed in control and µ1A-deficient cells. A weak immunofluorescence signal could be seen in control and µ1A-deficient cells after exposing the cells to anti-LAMP-1 antibody for 4 h and signal intensity did not differ between the cell lines. These data show that LAMP-1 can be transported to lysosomes independently of AP-1 and via a direct pathway avoiding transient appearance at the cell surface.

Fig. 6. LAMP-1 sorting in µ1A-deficient cells. (A and B) Co-localization at steady state of LAMP-1 and the lysosomal enzyme β-glucuronidase in control (A) and µ1A-deficient cells (B). (C and D) Anti-LAMP-1 antibody endocytosis over 2 h. AP-3-deficient mouse mocha cells and µ1A-deficient cells were co-cultured and γ-adaptin labeling was used to distinguish between AP-3- and µ1A-deficient cells. (C) Steady-state labeling of LAMP-1 (red) and γ-adaptin (green). (D) Steady-state labeling of γ-adaptin and labeling of LAMP-1 after anti-LAMP-1 antibody endocytosis.

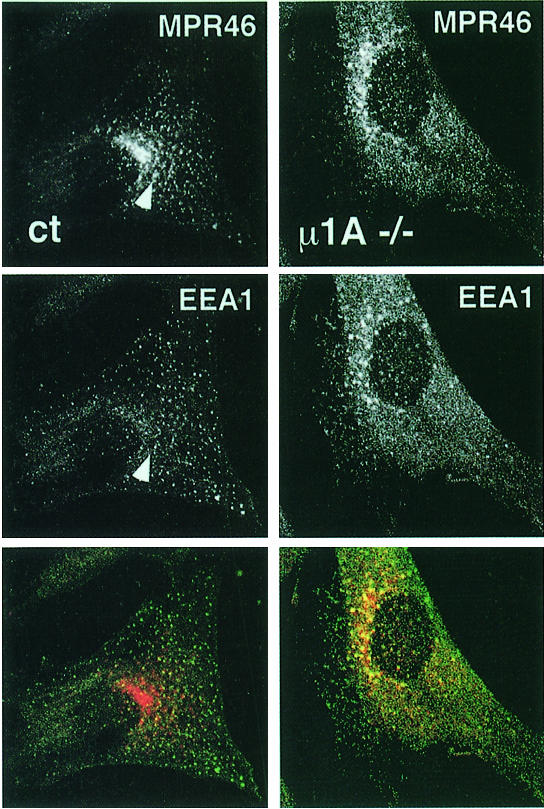

In contrast to LAMP-1 the two MPRs were clearly redistributed in µ1A-deficient cells. The predominant perinuclear TGN localization of MPR46 seen in control cells is changed to a more even distribution throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 7). MPR300, which in control cells is already less concentrated in the perinuclear area than MPR46, is also redistributed to vesicular structures throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 7). These peripheral MPR46-positive structures in µ1A-deficient cells also stained for the early endosome-associated protein EEA1 (Figure 8). A similar co-localization was observed for MPR300 and EEA1 in µ1A-deficient cells (not shown), while in control cells neither MPR46 nor MPR300 co-localized substantially with EEA1. Vesicles labeled only for MPR46 and not EEA1 most likely resemble transport vesicles recycling between endosomes and the plasma membrane. The data clearly indicate a redistribution of MPRs to early endosomes in cells that lack a functional AP-1. It should be noted that the distribution of EEA1 itself may also be affected by µ1A deficiency. In control cells the structures carrying EEA1 appear to be evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, while in µ1A-deficient cells they are consistently more concentrated in the area next to the nucleus (Figure 8).

Fig. 7. Distribution of MPR46 in control (A) and µ1A-deficient (B) cells and of MPR300 in control (C) and µ1A-deficient (D) cells.

Fig. 8. Co-localization of MPR46 (red) and EEA1 (green) by indirect immunofluorescence (confocal images). The arrow marks vesicle stained for both proteins in control cells.

In order to verify that the phenotypic variations observed in µ1A-deficient fibroblasts are related to the absence of µ1A-adaptin, the cells were stably transfected with the µ1A-cDNA under the control of the MPSV promoter. Expression of µ1A to the level of control cells restored binding of γ-adaptin and clathrin to the TGN (Figure 3) and the perinuclear enrichment of the MPRs as well as sorting of cathepsin D.

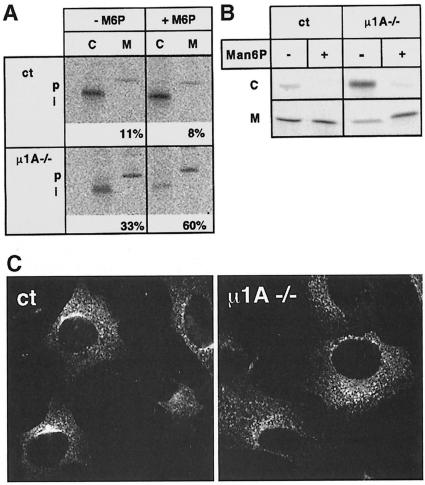

Effect of µ1A deficiency on M6P-receptor trafficking

A major function of MPRs is the binding of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes at the TGN and their transport to endosomes/lysosomes via AP-1-containing CCVs. The steady-state redistribution of MPRs from the TGN to the endosome may compromise the sorting of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes, leading to their secretion in µ1A-deficient cells. Sorting was analyzed by labeling the cells over 1 h with [35S]methionine followed by a 4 h chase period and immunoprecipitation of cathepsin D from the cells and the medium. While in control cells only 11% of the newly synthesized cathepsin D accumulated as a precursor in the medium, this fraction increased to 33% in µ1A-deficient cells. In both cell lines the remaining cathepsin D was recovered intracellularly as the proteolytically processed form that is generated in endosomes/lysosomes (Figure 9A). Since secretion of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes can be corrected by subsequent endocytosis of the secreted enzymes through MPR300, the experiment was repeated in the presence of 5 mM mannose 6-phosphate (Man6P). In accordance with previous studies Man6P had no effect on the sorting of cathepsin D in control cells, while in µ1A-deficient cells the fraction of cathepsin D precursor in the medium increased to 60% (Figure 9A). This indicates that in µ1A-deficient cells the bulk of cathepsin D precursor is missorted to the medium. About half of it, however, can be recaptured through MPR300-mediated endocytosis.

Fig. 9. Sorting and endocytosis of lysosomal enzymes in µ1A-deficient cells. (A) Sorting of newly synthesized cathepsin D in control (ct) and µ1A-deficient (µ1A–/–) cells in the absence and presence of 5 mM Man6P and restoration of cathepsin D sorting by ectopic expression of µ1A. Cells were metabolically labeled for 1 h and chased for 4 h. Cathepsin D was immunoprecipitated from the cells (C) and the medium (M). The precursor (p) and proteolytically processed intermediate forms (i) of cathepsin D are indicated. Numbers indicate the percentage of cathepsin D secreted into the medium as quantified by phosphoimager analysis. (B) Endocytosis of metabolically labeled [35S]ASA by MPR300 from the medium by control and µ1A-deficient fibroblasts at 37°C during a 4 h incubation in the absence (–) or presence (+) of 5 mM Man6P in the medium. (C) Endocytosis of anti-MPR46 antibodies from the medium by control (ct) and µ1A-deficient (µ1A–/–) cells.

The endocytic capacity of the MPR300 in µ1A-deficient cells was measured by incubating the cells for 2 h in the presence of [35S]arylsulfatase A (ASA), a lysosomal protein known to be internalized via MPR300 (Kasper et al., 1996). The amount of [35S]ASA recovered in µ1A-deficient cells was 7-fold higher (9303 ± 465 c.p.m./mg, n = 2) than in control cells (1495 ± 99 c.p.m./mg, n = 2) (Figure 7B). The internalization was sensitive to the presence of 5 mM Man6P in the medium.

Next we examined lysosomal delivery by the internalization of [125I]PMP–BSA (pentamannose 6-phos phate-substituted bovine serum albumin), a MPR300 ligand that is degraded after its delivery to lysosomes (Braulke et al., 1987). When incubated overnight in the presence of 40 ng [125I]PMP–BSA (300 000 c.p.m.), µ1A-deficient cells internalized 80% and control cells 10% of the offered ligand. In µ1A-deficient as well as in control cells ∼95% of the internalized ligand had been degraded. The 125I-labeled degradation products were recovered as trichloroacetic acid-soluble material in the medium (not shown). These data demonstrate that the redistribution of MPR300 in µ1A-deficient cells results in increased capacity to internalize Man6P-containing ligands, which then are delivered to lysosomes.

Missorting of MPR46 to the plasma membrane was analyzed by anti-MPR46 antibody endocytosis from the culture medium and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 9C). After 1 h of antibody endocytosis by control cells, perinuclear and peripheral cytoplasmic vesicles contained anti-MPR46 antibody. µ1-deficient cells did not contain anti-MPR46 antibodies in perinuclear vesicles. Only peripheral cytoplasmic vesicles were labeled. The same result was obtained after endocytosis of anti-MPR300 antibodies (not shown).

Endocytosis of 125I- or Cy3-labeled transferrin (not shown) did not reveal differences in AP-2-mediated transferrin endocytosis between control and µ1A-deficient cells. Endocytosed transferrin did not co-localize with MPR46 and only few vesicles showed co-localization with MPR300 (not shown). Incubation of cells for 30 or 60 min at 37°C in the presence of horseradish peroxidase and determination of the cell-associated peroxidase activity did not reveal any difference between control and µ1A-deficient cells (not shown), indicating that fluid phase endocytosis is not affected by µ1A deficiency.

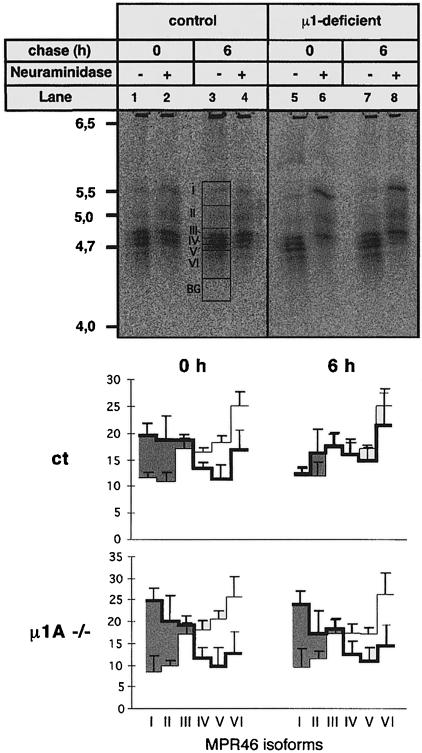

Defective MPR46 recycling from endosomes to the TGN

The previous experiments had demonstrated a redistribution of MPR46 and MPR300 from the TGN to endosomes, and as a result a misrouting of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes into the secretions. In the case of cathepsin D half of the secreted precursor can be recaptured and transferred to lysosomes due to an enhanced capacity of the µ1A-deficient cells to internalize lysosomal enzymes. One of the possible explanations for an accumulation of MPR46 in endosomes and depletion in the TGN could be that transport of MPR46 from endosomes back to the TGN is impaired in µ1A-deficient cells (Duncan and Kornfeld, 1988). This pathway was analyzed by following the resialylation of MPR46 that had been desialylated at the cell surface (Duncan and Kornfeld, 1988; Braun et al., 1989). MPR46 has two complex type N-glycans (Wendland et al., 1991). Heterogeneity of sialylation results in six isoforms discernible by isoelectric focusing (IEF). Cells were metabolically labeled for 16 h with [35S]methionine and chased for 1 h. After this labeling protocol only 12% (control cells) to 9% (µ1A-deficient cells) of the labeled MPR46 is non-sialylated and exhibits a pI of 5.5 (Figure 10, lanes 1 and 5). This fraction remains unsialylated during a chase of 6 h (Figure 10, lanes 3 and 7). Incubation of the cells at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of neuraminidase increased the fraction of non-sialylated MPR46 (pI 5.5) from 12 to 20% in control cells (Figure 10, lane 2) and from 9 to 25% in µ1A-deficient cells (Figure 10, lane 6). In control cells 9.8% and in µ1A-deficient cells 13.5% shift to isoforms with fewer sialic acid residues. This indicates that in total a minimum of 17.8% of the MPR46 have been exposed to neuraminidase at the cell surface in control cells. In µ1A-deficient cells the fraction is 29.5%. If the incubation with neuraminidase was carried out at 0°C, the fraction of desialylated MPR46 in control and µ1A-deficient cells was ∼3% (data not shown). This indicated that at 37°C, within 1 h, 17.8% of MPR46 has been transported to the cell surface in control cells and 29.5% in µ1A-deficient cells. However, this calculation underestimates the fraction of receptors exposed at the cell surface, because only a fraction of partially desialylated receptors are detected. This first part of the experiment supports the notion that in µ1A-deficient cells the fraction of MPR46 cycling via the cell surface is increased ∼2-fold.

Fig. 10. Desialylation and resialylation of MPR46. Cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine for 16 h. After a 1 h chase cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the absence (–) or presence (+) of neuraminidase. Neuraminidase-containing medium was replaced with medium containing neuraminidase inhibitor. Cells were either harvested or further incubated for 6 h. MPR46 was immunoprecipitated and separated by IEF. Upper panel: representative IEF gel. Areas in lane 3: I–VI represent non-sialylated (I) and sialylated isoforms (II–VI); BG is the area subtracted for background signal. Lower panel: quantification of MPR46 isoforms of three independent experiments by phosphoimager analysis. Thick lines, MPR46 isoforms in neuraminidase-treated cells; thin lines, MPR46 isoforms in untreated cells. The net desialylation is represented by the shaded area.

When cells that had been treated with neuraminidase for 1 h were subsequently incubated for 6 h at 37°C in medium without neuraminidase, but supplemented with the neuraminidase inhibitor 2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-N-acetylneuraminic acid, the fraction of non-sialylated MPR46 decreased in control cells to 12.6% (Figure 10, lane 4) and the pattern of the sialylated forms was restored. In µ1A-deficient cells desialylated MPR46 failed to become resialylated and the pattern of sialylated isoforms did not change (Figure 10, lane 8). These data indicate that the desialylated MPR46 is efficiently resialylated in control cells, but not in µ1A-deficient cells. Sialylation is accomplished within the TGN, where sialyltransferases are located as resident enzymes that do not recycle between the cell surface and the TGN (Ma et al., 1997). We conclude from these data that return of MPR46 from the endosome to the TGN is severely impaired in µ1A-deficient cells.

The inability of MPR46 to return from the endosomes to the TGN may result in an accelerated delivery of the receptor to lysosomes; therefore, we examined the steady-state concentration of MPR46 and MPR300 and the half-life of the two receptors in control and µ1A-deficient cells. The expression level of the MPRs as examined by Western blotting was not affected by µ1A deficiency. The stability of the two MPRs examined in cells labeled with [35S]methionine for 16 h and chased for up to 24 h was likewise not affected (not shown).

Discussion

µ1A is essential for embryonic development

Deficiency of µ1A-adaptin is lethal at day 13.5 of embryonic development. The normal growth of µ1A-deficient fibroblasts, the development of organs and the morphological alterations preceding tissue formation, which can still be observed in µ1A-deficient embryos, demonstrate that most cell types can survive without a functional AP-1. This is in accordance with the observation that yeast cells lacking µ1A-adaptin, or all of the adaptins, do not show a phenotype (Stepp et al., 1995; Huang et al., 1999). In multicellular organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and mice, AP-1 function is more critical. Mutation of µ1A-adaptin in C.elegans reduces viability after hatching of the larvae and survivors display the uncoordinated movement phenotype (Lee et al., 1994). The µ1A-deficient embryos show extensive hemorrhages in the ventricles and the spinal canal, but analysis of vascularization by whole-mount anti-PECAM-1 immunohistochemistry did not reveal differences between control and µ1A-deficient animals (C.Meyer and P.Schu, unpublished). Tissue preservation was difficult during the preparation of µ1A-deficient embryos for cryosectioning. This indicates that cell–cell or cell–extracellular matrix contacts are weaker in these animals. Eosin–hematoxylin-stained paraffin sections did not reveal altered tissue morphology. The cause of death of µ1A-deficient embryos is still elusive.

µ1A-deficient embryos develop primitive organs, while deficiency of γ-adaptin results in embryonic death at day 3.5 (Zizioli et al., 1999). This indicated that the embryonic survival and organ development of µ1A-deficient embryos is a function of the remaining AP-1 subunits, possibly in combination with µ1A homologs. The epithelial specific isoform µ1B is such a µ1A homolog, which is expressed in all polarized epithelial cells (Ohno et al., 1999). Expression of µ1B in µ1A-deficient fibroblasts restores binding of γ-adaptin to the TGN (P.Schu, unpublished). Residual binding of γ-adaptin to membranes in polarized epithelial cells in µ1A-deficient embryos supports the observation made in LLC-PK1 cells that µ1B forms an AP-1B complex with the ubiquitously expressed γ-adaptin, which mediates basolateral sorting of the LDL receptor (Fölsch et al., 1999). Protein sorting mediated by AP-1B in polarized epithelial cells of µ1A-deficient embryos can explain the phenotypic differences of the γ- and µ1A-adaptin ‘knock-outs’. The AP-1B complex of the polarized epithelial trophoblasts might enable the µ1A-deficient blastocysts to hatch out of the zona pellucida, invade the uterine wall and proceed through the early stages of development. We can also exclude the existence of additional µ1A-adaptin homologs in other tissues, such as the brain and the liver, which demonstrates that early stages of organ development do not require AP-1 function.

Protein sorting in µ1A-deficient cells

In the absence of µ1A the remaining AP-1 adaptins are unable to bind to the TGN and clathrin coats are not assembled at the TGN. The restoration of AP-1 and clathrin binding after re-expression of µ1A illustrates the critical role that µ1A has for binding of AP-1 to the TGN and that in turn AP-1 bound to the TGN has for clathrin coat assembly.

Among the cargo molecules identified in AP-1-containing CCVs are LAMP-1 and the two MPRs (Hille-Rehfeld, 1995; Höning et al., 1996). However, loss of AP-1 function does not result in missrouting of LAMP-1 to the cell surface, as would be expected, and does not impair targeting to lysosomes. This indicates that AP-1 is not essential for the direct routing of LAMP-1 from the TGN to endosomes. In contrast to AP-1, AP-3 appears to be critical for intracellular targeting of LAMP-1. In fibroblasts from the δ-adaptin mutant mocha, LAMP-1 transiently appears at the cell surface (Kantheti et al., 1998; Le Borgne et al., 1998; Dell’Angelica et al., 1999). This indicates that AP-3 might mediate lysosomal targeting of LAMP-1 at the TGN. In contrast to targeting of LAMP-1, that of MPR46 critically depends on AP-1. Loss of AP-1 results in a redistribution of MPRs from the TGN to endosomes. For the MPR46 we could demonstrate that this redistribution is caused by an impaired recycling from endosomes to the TGN. It remains to be determined whether recycling of other membrane proteins such as MPR300 and furin, which utilize the same or a similar pathway, is also impaired. The steady-state distribution of TGN38 is not altered in µ1A-deficient cells, which is in agreement with in vitro data demonstrating interaction of its cytoplasmic tail with µ2, but not with µ1A (Stephens et al., 1997).

The markedly enhanced internalization of lysosomal enzymes mediated by MPR300 is an additional effect that can be explained by the redistribution of MPRs in AP-1-deficient cells. The impaired endosome to TGN transport of MPRs apparently favors their trafficking along the alternative recycling pathway connecting endosomes with the cell surface.

Is AP-1 directly involved in retrograde MPR46 transport?

The accumulation of MPRs in µ1A-deficient cells in endosomes that carry EEA1, the increased rate of MPR300-mediated endocytosis and the impaired recycling of MPR46 back to the TGN point to a function of AP-1 in mediating endosome to TGN transport. This would be a direct function if AP-1 is part of the transport machinery mediating endosome to TGN transport, or an indirect function if AP-1 is required for the delivery of components to endosomes critical for endosome to TGN transport. In an in vitro system of endosome to TGN transport MPR300 transport is independent of clathrin and thus of AP-1 (Draper et al., 1990). A direct role of AP-1 in endosome to TGN transport is, however, suggested by studies in which PACS-1 was depleted from cells. PACS-1 functions as a linker between the cytoplasmic domains of proteins such as MPR300 and furin and the AP-1. Expression of PACS-1 antisense RNA impaired transport of MPR300 and furin from late endosomes to the TGN (Wan et al., 1998). In addition, AP-1, which is mainly found at the TGN, has also been detected on endosomal structures (Futter et al., 1998). In vitro reconstitution of the endosome to TGN transport (Itin et al., 1997) using membranes or cytosol from AP-1-deficient cells together with cytosol or membranes from control cells should allow us to answer this question.

Materials and methods

Gene isolation, mapping and targeting construct

The following primers were used to generate mouse µ1A cDNA from total kidney RNA by RT–PCR (Pharmacia, Freiburg; cDNA Kit): 5′CGGGATCCATGTCCGCCAGCGCCGTCT and 5′CGGGATCCCGGGCCTCTCACTGGGTCCGG (Nakayama et al., 1991). The cDNA was sequenced and used to screen a mouse phage DNA library in EMBL3 (a generous gift of A.Berns, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). An MspI polymorphism in Adtm1A between M.musculus and M.spretus was used to map the chromosomal locus. In M.musculus a 6 kb fragment and in M.spretus a 4 kb fragment hybridized with the cDNA. DNA from 94 animals, produced by crossing M.spretus with animals having a M.musculus/M.spretus genetic background, was hybridized after MspI incubation. The hybridization pattern was analyzed using a computer program (Jackson Laboratory, Maine). A 9.5 kb EcoRI fragment containing eight exons was subcloned into pBluescript SKII+ (Stratagene). A 3.3 kb EcoRI–KpnI fragment was subcloned and XhoI and BglII restriction endonuclease sites were introduced into exon n + 1 by oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis. Mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing. A 2.3 kb KpnI–KpnI fragment was ligated into the KpnI site yielding a 5.6 kb Adtm1A fragment. The neoR expression cassette from pMC1neopA (Stratagene) was cloned into the XhoI site as a 1.2 kb XhoI fragment and the construct with opposing open reading frames (ORFs) was used. The construct was linearized by NotI digestion and electroporated into the mouse 129SV/J embryonic stem cell line ES 14-1. Mutated ES cells were injected into day 3.5 p.c. blastocysts, which were transferred into the uteri of pseudopregnant foster mothers. Three male chimeras were mated with C57/Bl6 (outbred) and 129SV/J (outbred). Mice strains were purchased from Biological Research Laboratories, Basel, Switzerland. Colonies were kept in a central animal facility of the University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany.

Cell lines, antisera and microscopy

Embryonic fibroblast cell lines were established from day 11.5 embryos by continously passaging the cells (Todaro and Green, 1963). Adaptins and clathrin were detected with anti-γ-, anti-α, anti-β-adaptin and anti-clathrin heavy chain mouse monoclonal antibodies (Transduction Laboratories). Affinity-purified anti-σ1 antiserum was a generous gift from M.Robinson (Cambridge). Anti-LAMP-1 (1D4B) was a rat monoclonal antibody (DSHB; University of Iowa). An anti-µ1A peptide rabbit antiserum was generated against amino acids 295–310 of mouse µ1A. Anti-TGN38 was a gift from G.Banting (Bristol). Anti-cathepsin D rabbit antiserum, affinity-purified anti-MPR46 and anti-MPR300 antisera were generously provided by R.Pohlmann and A.Hille-Rehfeld, and anti-DHFR by M.Horst from our institute. Anti-EEA1 was a generous gift from H.Stenmark. Cy3-transferrin and transferrin for 125I labeling, and fluorescein isothiocyanate- and Texas Red-coupled secondary antibodies were from Jackson Immunoresearch. Anti-ZO-1 antisera were from T.Fleming. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Zeiss LSM 200 Series equipped with a Zeiss Plan Apochromat 63×/1.40 and Carl Zeiss LSM version 3.95 software. Images were processed for presentation using Adobe Photoshop version 3.0.5 and Deneba Canvas 5.0. Cells were fixed with 3% p-formaldehyde or methanol following standard protocols. Fluorescent LDL and BODIPY FL C5-ceramide (5 µM in serum-free DMEM over 10 min, 30 min chase in DMEM with 0.75 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA) were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and horseradish peroxidase was from Sigma.

Adaptor isolation

Cells were homogenized in 0.1 M MES buffer pH 6.5, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.02% NaN3 and 2 µg/ml pepstatin, 2 µg/ml leupeptin A, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 5 mM iodoacetamide by passing them 20 times through a 22 G needle. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 1000 g over 10 min. The supernatant was separated into a membranous and cytosolic fraction by centrifugation at 100 000 g over 45 min. Gel filtration of 50 µl of cytosol (5 mg/ml protein) was performed on a Superdex-200 column (Smart-System, Pharmacia) at a flow rate of 40 µl/min and a fraction volume of 50 µl. The column was calibrated with blue dextran, thyroglobulin, ferritin, catalase, aldolase, BSA, ovalbumin and cytochrome c. Proteins (50 µg of crude cell extract or entire gel filtration fractions) were resolved on 7.5 and 12.5% Laemmli gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were used for up to three analyses after stripping antibody complexes from the membrane by washing in 0.1 M NaOH over 5 min. Protein–antibody complexes were made visible by chemiluminescence (Super-Signal™, Pierce) and X-ray film exposure. X-rays were scanned and signals were quantified (Wincam Software).

In vitro binding of adaptor complexes

Cells grown on polylysine-coated coverslips were permeabilized by incubation for 5 min with ice-cold 25 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.2 containing 125 mM KOAc, 5 mM MgOAc, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mg/ml glucose and 25 µg/ml digitonin. Cells were incubated on ice over 15 min with cytosol of 2 (control cytosol) and 6 (µ1A-deficient cytosol) mg/ml protein in permeabilization buffer containing 1 mM ATP, 8 mM creatine phosphate, 80 µg/ml creatine kinase, 100 µM GTPγS and 5 µg/ml brefeldin A (Robinson and Kreis, 1992). Cells were fixed in methanol and processed for immunofluorescence as described. Cytosol was prepared as described above in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 0.2 mM DTT, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM iodoacetamide, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM PMSF.

Lysosomal enzyme sorting and endocytosis

Determination of enzymatic activities of lysosomal enzymes in the cells and culture medium and the distribution of newly synthesized cathepsin D in metabolically labeled cells were performed as described earlier (Köster et al., 1994). Radioactivity was quantified using a BioImager (Fuji, FUJIX BAS 1000). Endocytosis of [35S]ASA (Bresciani et al., 1992) and of [125I]PMP–BSA was performed as described (Braulke et al., 1987).

Neuraminidase treatment

Cells in 3 cm dishes were metabolically labeled overnight with 100 µCi of [35S]methionine/cysteine and then chased for 1 h. Fifty milliunits of neuraminidase (Vibrio cholerae, Boehringer Mannheim) were added in DMEM for 1 h at 37°C. The medium was removed, cells were washed with medium and incubated for 6 h in medium in the presence of 1 mM 2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-N-acetylneuraminic acid (Sigma) as described (Duncan and Kornfeld, 1988; Braun et al., 1989). Dishes incubated without neuraminidase served as controls. Cells were harvested and the neuraminidase inhibitor was adjusted to 0.1 mM in all the buffers. MPR46 was immunoprecipitated (MSC-1 antibody; Klumperman et al., 1993) and isoforms were resolved by IEF in a pH gradient from 4.0 to 6.5 (Braun et al., 1989) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). All bands seen in IEF represent MPR46 isoforms as demonstrated by their absence in immunoprecipitates performed with pre-immune serum or with extracts from MPR46-deficient cells (not shown) (Köster et al., 1993).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank A.Berns for providing the mouse DNA library, M.Robinson, H.Stenmark, G.Banting, R.Pohlmann, A.Hille-Rehfeld, M.Horst and T.Fleming for antibodies, and T.Braulke for PMP–BSA. We especially thank M.Wissel, N.Hartelt, J.Deussing and C.Hinners for their excellent technical assistance. This work is supported by the Fonds der chemischen Industrie and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- Alconada A., Bauer,U. and Hoflack,B. (1996) A tyrosine-based motif and a casein kinase II phosphorylation site regulate the intracellular trafficking of the varicella–zoster virus glycoprotein I, a protein localized in the trans-Golgi network. EMBO J., 15, 6096–6110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan B. and Balch,W. (1999) Protein sorting by directed maturation of Golgi compartments. Science, 285, 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J.S. and Dell’Angelica,E.C. (1999) Molecular bases for the recognition of tyrosine-based sorting signals. J. Cell Biol., 145, 923–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braulke T., Gartung,C., Hasilik,A. and von Figura,K. (1987) Is movement of mannose 6-phosphate-specific receptor triggered by binding of lysosomal enzymes? J. Cell Biol., 104, 1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M., Waheed,A. and von Figura,K. (1989) Lysosomal acid phosphatase is transported to lysosomes via the cell surface. EMBO J., 8, 3633–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani R., Peters,C. and von Figura,K. (1992) Lysosomal acid phosphatase is not involved in the dephosphorylation of mannose 6-phosphate containing lysosomal proteins. Eur. J. Cell Biol., 58, 57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica E., Shotelersuk,V., Aguilar,R., Gahl,W. and Bonifacino,J. (1999) Altered trafficking of lysosomal proteins in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome due to mutations in the β3A subunit of the AP-3 adaptor. Mol. Cell, 3, 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich J., Kastrup,J., Nielsen,B.L., Ødum,N. and Geisler,C. (1997) Regulation and function of the CD3γ DxxxLL motif: a binding site for adaptor protein 1 and adaptor protein 2 in vitro. J. Cell Biol., 138, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittié A.S., Thomas,L., Thomas,G. and Tooze,S.A. (1997) Interaction of furin in immature secretory granules from neuroendocrine cells with the AP1 adaptor complex is modulated by casein kinase II phosphorylation. EMBO J., 16, 4859–4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper R.K., Goda,Y., Brodsky,F.M. and Pfeffer,S.R. (1990) Antibodies to clathrin inhibit endocytosis but not recycling to the trans Golgi network in vitro. Science, 248, 1539–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J.R. and Kornfeld,S. (1988) Intracellular movement of two mannose 6-phosphate receptors: return to the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol., 106, 617–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fölsch H., Ohno,H., Bonifacino,J.S. and Mellman,I. (1999) A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells. Cell, 99, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter C.E., Gibson,A., Allchin,E.H., Maxwell,S., Ruddock,L.J., Odorizzi,G., Domingo,D., Trowbridge,I.S. and Hopkins,C.R. (1998) In polarized MDCK cells basolateral vesicles arise from clathrin-γ-adaptin-coated domains on endosomal tubules. J. Cell Biol., 141, 611–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman J.N., Conibear,E. and Pearse,B.M. (1989) Specificity of binding of clathrin adaptors to signals on the mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor. EMBO J., 8, 1041–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilker R., Spiess,M. and Crottet,P. (1999) Recognition of sorting signals by clathrin adaptors. BioEssays, 21, 558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille-Rehfeld A. (1995) Mannose 6-phosphate receptors in sorting and transport of lysosomal enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1241, 177–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J. and Robinson,M. (1998) Clathrin and adaptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1404, 173–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J., Bright,N.A., Rous,B. and Robinson,M.S. (1999) Characterization of a fourth adaptor-related protein complex. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 2787–2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höning S., Griffith,J., Geuze,H.J. and Hunziker,W. (1996) The tyrosine-based lysosomal targeting signal in lamp-1 mediates sorting into Golgi-derived clathrin-coated vesicles. EMBO J., 15, 5230–5239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höning S., Sosa,M., Hille-Rehfeld,A. and von Figura,K. (1997) The 46 kDa mannose-6-phosphate receptor contains multiple binding sites for clathrin adaptors. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 19884–19890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K., D’Hondt,K., Riezman,H. and Lemmon,S. (1999) Clathrin functions in the absence of heterotetrameric adaptors and AP180-related proteins in yeast. EMBO J., 18, 3897–3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itin C., Rancano,C., Nakajima,Y. and Pfeffer,S.R. (1997) A novel assay reveals a role for soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion attachment protein in mannose 6-phosphate receptor transport from endosomes to the trans Golgi network. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 27737–27744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantheti P. et al. (1998) Mutation of the AP-3 δ subunit in the mocha mouse links endosomal cargo transport to storage deficiency in platelets, melanosomes and neurotransmitter vesicles. Neuron, 21, 111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper D., Dittmer,F., von Figura,K. and Pohlmann,R. (1996) Neither type of mannose 6-phosphate receptor is sufficient for targeting of lysosomal enzymes along intracellular routes. J. Cell Biol., 134, 615–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumperman J., Hille,A., Veenendaal,T., Oorschot,V., Stoorvogel,W., von Figura,K. and Geuze,H.J. (1993) Differences in the endosomal distributions of the two mannose-6-phosphate receptors. J. Cell Biol., 121, 997–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köster A., Saftig,P., Matzner,U., von Figura,K., Peters,C. and Pohlmann,R. (1993) Targeted disruption of the Mr 46000 mannose 6-phosphate receptor gene in mice results in missrouting of lysosomal proteins. EMBO J., 12, 5219–5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köster A., von Figura,K. and Pohlmann,R. (1994) Mistargeting of lysosomal enzymes in Mr 46 000 mannose 6-phosphate receptor-deficient mice is compensated by carbohydrate-specific endocytotic receptors. Eur. J. Biochem., 224, 685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Borgne R., Alconada,A., Bauer,U. and Hoflack,B. (1998) The mammalian AP-3 adaptor-like complex mediates the intracellular transport of lysosomal membrane glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 29451–29461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Jongeward,G.D. and Sternberg,P.D. (1994) unc1-1, a gene required for many aspects of Caenorhabtidis elegans development and behaviour, encodes a clathrin associated protein. Genes Dev., 8, 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Qian,R., Rausa III,F.M. and Colley,K.J. (1997) Two naturally occuring α-2,6-sialyltransferase forms with a single amino acid change in the catalytic domain differ in their catalytic activity and proteolytic processing. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin O.C. and Pagano,R.E. (1994) Internalization and sorting of a fluorescent analogue of glucosylceramide to the Golgi apparatus of human skin fibroblasts: utilization of endocytic and nonendocytic transport mechanisms. J. Cell Biol., 125, 769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews P.M., Martinie,J.B. and Fambrough,D.M. (1992) The pathway and targeting signal for delivery of the integral membrane glycoprotein LEP100 to lysosomes. J. Cell Biol., 118, 1027–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter K. and Mellman,I. (1994) Mechanisms of cell polarity: sorting and transport in epithelial cells. Curr. Biol., 6, 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méresse S. and Hoflack,B. (1993) Phosphorylation of the cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor is closely associated with its exit from the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol., 120, 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama Y., Goebl,M., O’Brine,G.B., Lemmon,S., Pingchang,C.E. and Kirchhausen,T. (1991) The medium chains of the mammalian clathrin-associated proteins have a homolog in yeast. Eur. J. Biochem., 202, 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H. et al. (1999) µ1B, a novel adaptor medium chain expressed in polarized epithelial cells. FEBS Lett., 449, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano R., Martin,O., Kang,H. and Haugland,R. (1991) A novel fluorescent ceramide analogue for studying membrane traffic in animal cells: accumulation at the Golgi apparatus results in altered spectral properties of the sphingolipid precursor. J. Cell Biol., 113, 1267–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page L.J. and Robinson,M.S. (1995) Targeting signals and subunit interactions in coated vesicle adaptor complexes. J. Cell Biol., 131, 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz U. and Schwarzmann,G. (1995) Golgi staining by two fluorescent ceramide analogues in cultured fibroblasts requires metabolism. Eur. J. Cell Biol., 68, 113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.S. and Kreis,T.E. (1992) Recruitment of coat proteins onto Golgi membranes in intact and permeabilized cells: effects of brefeldin A and G protein activators. Cell, 69, 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid S.L. (1997) Clathrin-coated vesicle formation and protein sorting: an integrated process. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 66, 511–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens D.J., Crump,C.M., Clarke,A.R. and Banting,G. (1997) Serine 331 and tyrosine 333 are both involved in the interaction between the cytosolic domain of TGN38 and the µ2 subunit of the AP2 clathrin adaptor complex. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 14104–14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp D.J., Pellicena-Palle,A., Hamilton,S., Kirchhausen,T. and Lemmon,S.K. (1995) A late Golgi sorting function for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Apm1p, but not for Apm2p, a second yeast clathrin AP medium chain-related protein. Mol. Biol. Cell, 6, 41–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro G.J. and Green,H. (1963) Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established cell lines. J. Cell Biol., 17, 299–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L., Molloy,S.S., Thomas,L., Liu,G.P., Xiang,Y., Rybak,S.L. and Thomas,G. (1998) PACS-1 defines a novel gene family of cytosolic sorting proteins required for trans-Golgi network localization. Cell, 94, 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland M., Waheed,A., Schmidt,B., Hille,A., Nagel,G., von Figura,K. and Pohlmann,R. (1991) Glycosylation of the Mr 46,000 mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Effect on ligand binding, stability and conformation. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 4598–4604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D.H. and Brodsky,F.M. (1992) 100-kD proteins of Golgi- and trans-Golgi network-associated coated vesicles have related but distinct membrane binding properties. J. Cell Biol., 117, 1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizioli D., Meyer,C., Guhde,G., Saftig,P., von Figura,K. and Schu,P. (1999) Early embryonic death of mice deficient in γ-adaptin. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 5385–5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]