Abstract

Hepatic steatosis is a major risk factor in liver transplantation. Use of machine perfusion to reduce steatosis has been reported previously at normothermic (37°C) temperatures, with minimal media as well as specialized defatting cocktails. In this work, we tested if sub-normothermic (room temperature) machine perfusion, a more practical version of machine perfusion approach that does not require temperature control or oxygen carriers could also be employed to reduce fat content in steatotic livers. Steatotic livers recovered from obese Zucker rats were perfused for 6 hours. A significant increase of very-low density protein (VLDL) and triglyceride (TG) content in perfusate, with or without a defatting cocktail, was observed although the changes in histology were minimal and changes in intracellular TG content were not statistically significant. The differences in oxygen uptake rate, VLDL secretion, TG secretion, venous resistance were similar in both groups. This study confirms lipid export during sub-normothermic machine perfusion, however the duration of perfusion necessary appears much higher than required in normothermic perfusion.

Keywords: steatosis, liver, machine perfusion, defatting

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LTx) is a very successful therapy for end-stage liver disease, but is restricted by donor organ shortage [1–3]. Livers from expanded criteria donors, including fatty livers, are increasingly used to expand donor pool [2]. However, a large number of donor steatotic livers go unused because their inferior quality leads to high risk of severe ischemia-reperfusion injury after LTx [2].

Extensive efforts have been tested to rescue steatotic livers for transplantation [4]. Since in the majority of such livers there is limited opportunity to treat the donor or organ prior to organ recovery, ideally the isolated liver grafts would be treated during the preservation period, which would provide direct access to the graft with no potential impact on the donor or other organs [4]. Machine perfusion (MP) is therefore a promising method to replace the current clinical standard, static cold storage (SCS). Indeed, several studies have reported the use of normothermic (~37°C) machine perfusion (NMP) for enhanced preservation of steatotic liver grafts [5–8]. NMP is advantageous as it keeps the graft at physiological temperature and supports physiological metabolism with continuous nutrition and oxygen supply [9]. Furthermore, it has been shown to resuscitate livers with warm ischemia (WI) injury from donors after cardiac death (DCD) [10;11]. Finally, NMP has been shown to decrease fat content, from mild steatosis of 30% to 15%, after prolonged (48 hours) NMP preservation [5]. By leveraging the active metabolism during NMP, pharmacological intervention can also be used together to stimulate lipid metabolism and rescue steatotic livers. A notable success has been the defatting cocktail previously developed by our group to remove about half of triglyceride (TG) content in 3 hours NMP [12].

While NMP is ideal for mimicking physiological parameters, from a clinical applicability perspective it is more complicated compared to SCS, creating a bottleneck for wide-spread adoption [13]. Sub-normothermic (~20°C) machine perfusion (SNMP) preservation is an alternative that is simpler in practice [6;7]. SNMP is performed at room temperature, eliminating the need for heating/cooling, has reduced needs on oxygen and nutrition supply, and hence can be used without red blood cells, which are used in all NMP perfusion protocols with successful transplant confirmation [9]. SNMP has been reported to be effective in resuscitating DCD livers by several groups including our own [14–16]. While SNMP was also reported to be a superior preservation modality for fatty livers based on enzyme release, energy storage, oxidative stress, and apoptosis after reperfusion [6;7], whether it can be used to reduce lipid content as shown in NMP protocols has not been previously tested. In the present study, we studied lipid secretion and content in fatty rat livers when perfused using SNMP with or without the defatting cocktail previously reported [12].

Materials and Methods

1. Animals

Obese Zucker rats (Charles River laboratories, Boston, MA) were used as the donor model. The animals were maintained in accordance with National Research Council guidelines and the approval by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, Massachusetts General Hospital.

2. Perfusate

The control perfusate (without defatting cocktail) was Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 3% wt/vol bovine serum albumin, 1.07mM lactic acid, and 0.11mM pyruvic acid. The defatting perfusate was the control perfusate supplemented with the 6 defatting agents (forskolin, GW7647, scoparone, hypericin, visfatin, and GW501516) as described elsewhere [12].

3. Liver procurement

Operation was started with transverse laparotomy under general anesthesia with isoflurane. Livers were dissected free from peritoneal attachment. Common bile duct was cannulated with 22-guage polyethylene tube (Surflo, Terumo, Somerset, NJ) for collecting bile during SNMP. Hepatic artery was ligated with 6-0 silk suture after heparin (300 IU) administration through infrahepatic vena cava. Livers were then flushed with 10ml cold (4°C) perfusate (control or defatting respectively, n=5/group) through 18-guage catheter on portal vein. Thoracic and infrahepatic vena cava were opened during flushing for outflow. Livers were taken out of body cavity after being flushed. 16-guage cuff was made on portal vein quickly (<4min) for the infusion of subsequent SNMP phase.

4. SNMP preservation

The SNMP system consists of an organ reservoir, a bubble trap, a membrane oxygenator from Radnoti (Monrovia, CA), a Masterflex L/S roller pump and a series of silicon tubing from Cole-Parmer (Vernon Hills, IL). Livers were perfused through an 18-guage catheter into the cuff on portal vein. A “Y”-shape connector was inserted on the catheter and connected to a vertical long tube open to air for monitoring the pressure at infusion site. 200ml perfusate was recirculated to perfuse livers for 6 hours at 20°C. The flow rate was constantly maintained at 1ml/min/g liver with partial oxygen pressure (pO2) above 400 mmHg at infusion. The samples of perfusate were taken before perfusion and every hour during SNMP. The biopsies were taken before and at the end of SNMP.

5. Perfusion Assays

pO2 and pH at infusion and outflow were measured by RapidLab Blood Gas Analyzer (Bayer Diagnostics, Leverkusen, Germany). The oxygen uptake rate (OUR) was calculated as the difference in pO2 between in and outflow and normalized with respect to liver weight.

The pressure at liver inlet was recorded at 0min, 10min, 30min, and hourly afterwards, as the height of water from the cuff to the top of the volume in the open tube. The venous resistance, in the unit of cmH2O/(ml/min), was calculated through dividing the pressure by the total flow rate to the whole liver.

VLDL secreted in perfusate was measured on the Piccolo Blood Analyzer with Lipid Panel from Abaxis (Sunnyvale, CA). The TG in perfusate was measured with the kit of Wako Diagnostics (Osaka, Japan).

6. Tissue Assays

Total TG content in liver tissue samples was determined by a TG kit (Wako Diagnostics, Osaka, Japan) and normalized to tissue sample weight. To eliminate the rat-to-rat variations in initial content, the ratio of TG content between before and after SNMP was calculated for each liver for comparing the defatting effect between groups.

Liver tissue samples were fixed with formaldehyde (4%), paraffin embedded, sectioned (5μm), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The histological slides were viewed with a Nikon light microscope and evaluated on the degree of steatosis.

6. Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Paired or unpaired Student t-test was used for comparison within or between groups. P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The average liver weights were 21.4±3.6 gram for the control and 22.9±5.8 gram for the defatting group. The difference between groups was not significant (p=0.58).

Perfusate Analysis

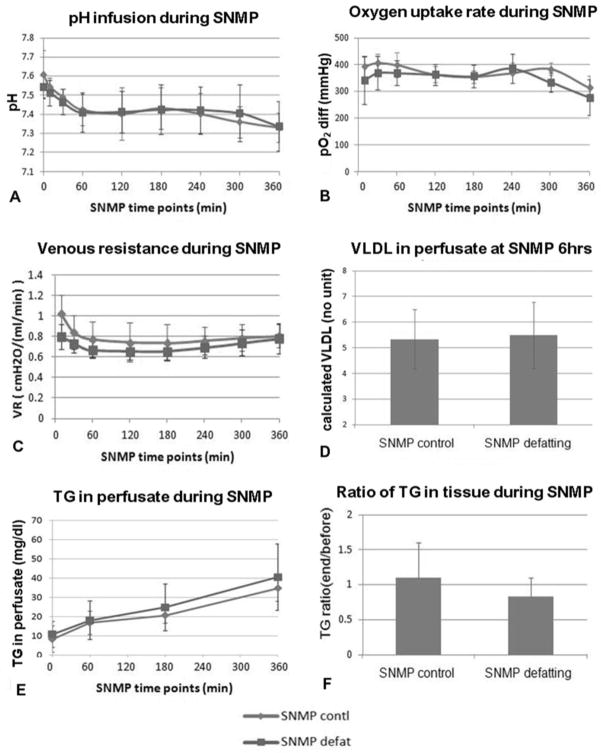

pH decreased significantly during perfusion (p<0.04) during SNMP, from 7.61±0.12 to 7.33±0.08 of the control and from 7.54±0.06 to 7.34±0.13 of the defatting group (Figure 1A). The differences between the two groups at any time point were not significant (p>0.28). The pO2 measured at outflow ranged in 20~100 mmHg, indicate the organs were not oxygen starved during perfusion. OUR was not statistically different between groups, and was generally quite stable during entire SNMP (control: 392±36 to 314±42 mmHg; defatting: 340±89 to 277±66 mmHg) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: the two groups had no acidosis during the 6 hours SNMP, indicated by stable pH from 7.5 to 7.3; 1B: oxygen consumption was high in both groups; 1C: the venous resistance had a slight decrease in the first hour of SNMP, possibly resulting from sphincter relaxation, and stayed stable afterwards; 1D–1E: VLDL and triglyceride (TG) content increasing in perfusate, indicated lipid export during SNMP; 1F: the reduction of TG content in liver tissue was not significant of either group.

Portal venous resistance decreased significantly (p<0.05) in the first hour of SNMP (control: 1.03±0.19 to 0.77±0.17 cmH2O/(ml/min); defatting: 0.80±0.12 to 0.67±0.08 cmH2O/(ml/min)) and were quite stable afterward (Figure 1C). In the beginning of SNMP the resistance had a significant difference (p=0.03) between groups but not at any time points later on.

The total VLDL secreted at the end of perfusion was similar in both groups (control: 5.3±1.2 mg/dl; defatting: 5.5±1.3 mg/dl; p=0.86), demonstrating release in SNMP as expected during lipid export (Figure 1D). The TG increased significantly during SNMP (control: 8.3±6.9 to 34.8±6.9 mg/dl; defatting: 10.8±6.8.0 to 40.5±17.3 mg/dl; p<0.01) (Figure 1E). The rate of increase was higher with the defatting cocktail, but this did not reach significance (p>0.44) during 6 hours of perfusion. Note that the initial values of VLDL and TG are both zero in the perfusate, therefore demonstrating active lipid export by the perfused livers in both groups (p≪0.05).

Tissue Analysis

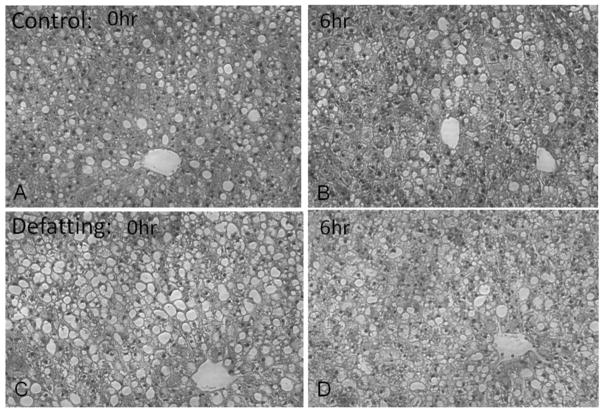

TG content in liver tissue did not change significantly within either group (p>0.16) during SNMP and also had no significant difference (p=0.26) between groups (The ratio of control: 1.1±0.5; defatting: 0.8±0.3) (Figure 1F). In histological evaluation, the steatosis before preservation was moderate to severe. After 6 hours SNMP, the change of steatosis was very diverse, but without consistent decrease in either group. Sinusoidal lumen was not substantially dilated in either group (Figure 2A–D).

Figure 2.

Histology showed moderate to severe steatosis of the control (A) and defatting (B) group before SNMP; steatosis was not decreased significantly in either group after 6 hours SNMP (C–D).

Discussion

In this study we observed lipid export during SNMP, with or without a defatting cocktail supplement. The results indicated an active lipid metabolism export despite the reduced temperature, which was not reported previously at 20°C [6;7]. However, during the 6 hours of preservation the reduction in lipid content did not reach statistical significance, and histology did not reveal consistent changes in either group. Similarly, venous resistance, which was recorded as a potential marker on the degree of steatosis since it should decrease in case of excessive fat removal and the consequent compression on sinusoidal lumen [17;18], was not markedly different during perfusion or between groups. The consistent resistance at most phase of SNMP implied the insignificant change of steatosis. The decrease of venous resistance in the first hour of SNMP was speculated to be an effect of sphincter relaxation in the same mechanism as the decreasing arterial resistance observed at kidney MP preservation [19].

Our overall conclusion here is that at room temperatures the lipid export rates are significantly slower compared to normothermic temperatures, and SNMP may be useful for defatting only if used for extended durations in the order of days.

Use of defatting cocktail yielded a slightly higher secretion of VLDL and TG secretions, but the differences were minor and did not reach statistical significance during the observation period. The main reason of the weak effect of the cocktail during SNMP can be speculated to be perfusion temperature. The active compounds in the cocktail work mostly as nuclear receptor ligands, which might be more sensitive to temperature than the rate of general metabolism [20]. A secondary factor could be the limited oxygen availability: pO2 at our outflow was at times below 50 mmHg which was compared to other SNMP studies [6;7]. It is worth noting that we previously demonstrated the same oxygenation method in successful preservation of DCD rat livers for transplant [16], but it is possible that the supply was nevertheless limiting for beta oxidation which the cocktail aims to enhance. Regardless, if an oxygen carrier is necessary for successful defatting, NMP is likely to be the more suitable approach since the major justification for SNMP is its operational simplicity.

In conclusion, our study indicates that SNMP is less than ideal for defatting steatotic liver grafts in perfusion, indicating that while machine perfusion is promising as a superior method of preservation for all marginal donor organs, pathology-specific protocols may be the ideal approach.

Acknowledgments

Support: Funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK096075, R01EB008678, R00DK080942, K99DK088962), and the Shriners Hospitals for Children are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Qiang Liu, Email: qiang.liu.med@gmail.com.

Tim Berendsen, Email: timberendsen@gmail.com.

Maria-Louisa Izamis, Email: yiapani@gmail.com.

Basak Uygun, Email: basak.saygili@gmail.com.

Martin Yarmush, Email: ireis@sbi.org.

Korkut Uygun, Email: uygun.korkut@mgh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Wolfe RA, Merion RM, Roys EC, et al. Trends in organ donation and transplantation in the United States, 1998–2007. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(4 pt 2):869–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durand F, Renz JF, Alkofer B, et al. Report of the Paris consensus meeting on expanded criteria donors in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(12):1694–1707. doi: 10.1002/lt.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg CL, Steffick DE, Edwards EB, et al. Liver and intestine transplantation in the United States 1998–2007. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(4 pt 2):907–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Rougemont O, Lehmann K, Clavien PA. Preconditioning, organ preservation, and postconditioning to prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury to the liver. Liver Transplantation. 2009;15:1172–1182. doi: 10.1002/lt.21876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamieson RW, Zilvetti M, Roy D, et al. Hepatic steatosis and normothermic perfusion-preliminary experiments in a porcine model. Transplantation. 2011;92(3):289–295. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318223d817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vairetti M, Ferrigno A, Carlucci F, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion protects steatotic livers against preservation injury: a potential for donor pool increase? Liver Transpl. 2009;15(1):20–29. doi: 10.1002/lt.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boncompagni E, Gini E, Ferrigno A, et al. Decreased apoptosis in fatty livers submitted to subnormothermic machine-perfusion respect to cold storage. Eur J Histochem. 2011;55(4):e40. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2011.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bessems M, Doorschodt BM, Kolkert JL, et al. Preservation of steatotic livers: a comparison between cold storage and machine perfusion preservation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(4):497–504. doi: 10.1002/lt.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monbaliu D, Brassil J. Machine perfusion of the liver: past, present and future. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(2):160–166. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328337342b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brockmann J, Reddy S, Coussios C, et al. Normothermic perfusion: a new paradigm for organ preservation. Ann Surg. 2009;259(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a63c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fondevila C, Hessheimer AJ, Masthuis MH, et al. Superior preservation of DCD livers with continuous normothermic perfusion. Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):1000–1007. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822b8b2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagrath D, Xu H, Tanimura Y, et al. Metabolic preconditioning of donor organs: defatting fatty livers by normothermic perfusion ex vivo. Metab Eng. 2009;11(4–5):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Izamis M, Berendsen T, Uygun K, et al. Addressing the liver organ donor shortage with ex vivo organ perfusion. Journal of Healthcare Engineering. 2012;3:279–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrigno A, Rizzo V, Boncompagni E, et al. Machine perfusion at 20°C reduces preservation damage to livers from non-heart beating donors. Cryobiology. 2011;62(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolboom H, Izamis ML, Sharma N, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion at both 20C and 30C recovers ischemic rat livers for successful transplantation. J Surg Res. 2012;175(1):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berendsen T, Bruinsma B, Lee JW, et al. A simplified subnormothermic machine perfusion model restores ischemically damaged liver grafts in a rat model of orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Res. 2012;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2047-1440-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imber CJ, St Peter SD, Handa A, et al. Hepatotic steatosis and its relationship to transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8(5):415–423. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.32275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ijaz S, Yang W, Winslet MC, et al. Impairment of hepatic microcirculation in fatty liver. Microcirculation. 2003;10(6):447–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jochmans I, Moers C, Smits JM, et al. The prognostic value of renal resistance during hypothermic machine perfusion of deceased donor kidneys. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2214–2220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita S, Hamamoto I, Nakamura K, et al. Isolated perfusion of rat livers: effect of temperature on O2 consumption, enzyme release, energy store, and morphology. Nippon Geka Hokan. 1993;62:58–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]