Introduction

Background

Despite the epidemic of childhood obesity,1, 2 effective and sustainable intervention approaches to help children lose weight or maintain their weight as they grow remain elusive. With one in three children today being overweight or obese, it is critical to identify effective methods for weight management in these children to reduce their risk for future health problems.3-5 Several clinical and individualized approaches for weight reduction in children have been developed and some show promise.6-23 However, few approaches have shown substantial and/or sustained benefits in children.5 Further, many previous studies have involved non-representative samples of economically disadvantaged children, wide age ranges, absence of stratification by risk, and short follow-up periods - limiting their generalizability.24

Childhood obesity is of great concern for both the current health of the child and the increased risk of developing more severe health problems as these children mature. There is significant evidence of associated co-morbidities with obesity in childhood, including hypertension, insulin resistance, diabetes, lipid abnormalities, and sleep-disordered breathing.16, 25-27 Moreover, children who are overweight are significantly more likely to have coronary heart disease and resulting earlier mortality when they reach adulthood.28-32 Treatment of these obesity-related co-morbidities has been estimated to have direct medical costs of $147 billion annually in the U.S.33

In addition to biological contributors to obesity, there is strong evidence identifying several behavioral, contextual, and environmental factors as critical underpinnings of the growing prevalence of pediatric obesity.34-45 Family, school, peers, community, and policy provide the environmental contexts that shape children's energy intake and expenditure - and therefore together influence the development of obesity and its co-morbidities.46 Viewing childhood obesity from this socio-ecological perspective43, 47-49 suggests that to gain traction in treating obesity, it is important to target more than one level of environmental influence. Interventions that target multiple environments (e.g., home, school, neighborhood) are likely to be more powerful in reducing obesity than interventions addressing only one. This may be particularly true for young adolescents,50-52 who are increasingly influenced by peers and environments outside the home.

Study Aims

The primary aim of this study is to compare the effects of three distinct behavioral obesity management interventions on BMI in overweight/obese middle school, urban youth. This study also assesses the additive effect of an enriched school-based intervention on BMI. Secondary aims are to: (a) assess the effects of the interventions on cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, lipids, C-reactive protein [CRP], body composition, biomarkers, fitness); (b) examine the effects of the interventions on participants' diet, physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep, and quality of life; and (c) explore whether the impact of the interventions on relevant outcomes is influenced by selected socioeconomic and demographic factors, environmental (home, school, neighborhood) factors, peer norms, and personal and psychosocial characteristics of the child and parent(s)/guardians.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design

IMPACT (Ideas Moving Parents and Adolescents to Change Together) is a randomized control trial with three intervention arms (SystemCHANGE [SC], HealthyCHANGE [HC], and active education-only control.) Participants (n=360 middle school children and an index family member/guardian) are randomized equally to these three intervention arms. By design, 50% of the participants were randomized in Year 1, and 50% of the sample will be randomized in Year 2 of the trial. In addition, approximately half of the participants are also students enrolled in a local K-8 public or charter school that offers an innovative community-sponsored fitness program, augmented by study-supported navigators. Mediator, moderator, and outcome measures are assessed at baseline and at 12, 24, and 36 months after randomization. The trial at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is one of four projects funded under a multi-site NIH-funded collaborative referred to as the Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment Research (COPTR) program sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Conceptual Model

The IMPACT study addresses obesity in urban youth by focusing on two levels of the child's environment: the child-family environment and the school-community environment. The primary goals of both the child-family and the school interventions are to reduce BMI by producing changes in lifestyle (diet, physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep, and stress management). Figure 1 illustrates the proposed relationships among the major study variables and their corresponding study aims. Our primary aim is to determine the effect of the two innovative child-family interventions (SystemCHANGE, HealthyCHANGE) compared to a brief education-only approach (control group), on reducing BMI (Path A), as well as assess the moderating impact of an enriched school environment (Path B).

Figure 1. IMPACT Conceptual Framework.

BMI is considered a distal outcome as it depends on changes in other more proximal outcomes – dietary intake, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and sleep. As part of our secondary aims, we will explore the impact of the child-family interventions and the moderating impact of the enriched school environment on these more proximal outcomes (Paths D and C, respectively), as well as secondary outcomes, including cardiovascular risk factors, body composition, cost and quality of life (also Path A).

Proposed mediators through which the interventions effect changes in both proximal and distal outcomes are: child's self-efficacy, social support, motivation, and family problem-solving, systems thinking, self-regulation (Paths E and F). The mediators represent the targeted approaches of each intervention (e.g., systems thinking for SystemCHANGE, motivation for HealthyCHANGE). Lastly, we will explore potential moderators that influence the degree to which the interventions are effective, including the family's socioeconomic status and demographic characteristics, personal characteristics of the child, parent/guardian, and family (including physiological and psychosocial characteristics), the child's physical and social environment (neighborhood, school, and family), and peer norms surrounding nutrition, physical activity and perceived environment (Paths G). We posit that these factors may moderate the impact of the interventions on outcomes, as well as interventions on the program-specific mediators.

Study Setting and Population

The IMPACT trial targets middle-school, urban, low-income, minority (predominately African American and Hispanic), children who are overweight/obese living in the Cleveland inner city. Recruitment is conducted in conjunction with a large urban school district and charter schools. Over half of the city's children live in single-parent households, 75% are on public health insurance, and 42% of 5-17 year olds live in poverty.53 Local school and community data also reveal that approximately 40% of the children are overweight or obese, 60% of youth do not exercise regularly, less than 20% report daily physical education, and over 63% watch three or more hours of TV daily.54

From its conception, the IMPACT study has involved its community partners: parents, students, teachers, representatives from parent liaison groups, the local school district, local charter schools and the local YMCA. Regular feedback, advice and guidance are sought from the study's community advisory board to maintain successful study recruitment and retention. In addition to solidifying our partnerships with the community, in Years 1 and 2 of the IMPACT project considerable formative work was completed that informed the design of the main trial. During this period, we conducted focus groups with children and parents to engage them as co-designers of the intervention and assessment protocols, collected available school- and neighborhood-level environmental data for use in the main trial's analyses, and conducted a one-year pilot study to assess feasibility and acceptability of the recruitment, intervention, measures, and data collection protocols.

Eligibility and Exclusions

Child inclusion criteria are: (1) entering 6th grade; (2) BMI ≥85th percentile determined from height and weight measurements; and (3) provision of consent by parents and assent by children. Child exclusion criteria are: (1) taking medications that alter appetite or weight; (2) stage 2 hypertension or stage 1 hypertension with end organ damage (e.g., left ventricular hypertrophy, microalbuminuria); (3) sickle cell disease; (4) severe behavioral problems that preclude group participation as reported by parent/guardian; (5) involvement in another weight management program; (6) family expectation to move from the region within 1 year, or (7) the presence of a known medical condition that itself causes obesity (e.g., Prader-Willi syndrome). ADHD medications are not an exclusion criterion because of their widespread use in this population, but their use will be measured. Additionally, known co-morbidities such as hyperlipidemia, asthma, and sleep apnea are not themselves reasons for exclusion as they represent co-morbidities commonly found in overweight/obese youth, and to exclude them could make the population non-representative. Disabilities (e.g., blindness, hearing loss) are accommodated using the services of a laboratory that focuses on the full inclusion of persons with disabilities in research directed by one of the investigators.55

The study participants also include one index parent/guardian for each child participant. If more than one parent/guardian is available, we ask the parent/guardian signatory (index study parent) to be the one likely to be most available to bring the child to visits. Parent/guardian inclusion criteria are being the parent or guardian of an eligible child and being able to attend data collection sessions.

Recruitment

The study sample is comprised of 360 children who are enrolled over two years (2012 and 2013) in two cohorts. In each of these years, between January and May, approximately 3,200 children in the 5th grade within the urban school district (including some charter schools) are screened for their BMI as part of student service-learning engagement projects at the School of Nursing and the Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods at Case Western Reserve University. The schools then provide the results of the screening to the IMPACT project team with contact information (including parent/guardian names, phone numbers and addresses) for all screened students who are potentially eligible for this project (i.e., BMI ≥ 85th percentile) – excluding those children whose parents/guardians opted out of further contact. The IMPACT team subsequently recruits all students near the end of 5th grade and the start 6th grade. In each of the two years of recruitment, we expect approximately 1,200 children who meet BMI eligibility standards for this study.

Data from our focus groups and parents guided our design of the recruitment process. Following receipt of the list of names of children who are potentially eligible for the study, an information flyer describing the study with a letter explaining that a member of the study team will be contacting them by telephone is sent to the homes of parents/guardians of the children. An IMPACT team member then calls the parent/guardian and offers more information about the study, including an in-person meeting at a convenient time and location of the family's choice. If the parent/guardian expresses immediate interest in the study, a pre-screening to determine further eligibility is completed during the recruitment telephone call. Using a Human Subjects Institutional Review Board -approved script, the prescreening includes informing parents/guardians about what information will be collected related to their child's personal and medical history, what will be done with the information collected, and receipt of parent consent to collect that information. Parents/guardians who agree are then asked questions about their child's past medical history, illnesses, and current medications (see exclusion criteria above) to further determine child eligibility for the study. Families indicating agreement to participate are scheduled for an intake visit at the Clinical Research Unit (CRU) at one of two large hospital systems associated with the university study site. At the intake visit, informed consent for study participation is reviewed with parents, and assent is obtained from the child.

Randomization and Assignment to Study Groups

Participants are randomly assigned to one of the three study groups using the minimization method.56, 57 As compared to simple random assignment or to stratified randomization using the permuted blocks approach, this technique has been shown to achieve better balance between study group assignments within levels of stratification variables.56 We attempt to ensure balance across the three study groups in three key variables: obesity status (BMI in 85th- 94th percentile vs. BMI ≥ 95th percentile); baseline blood pressure (elevated [either SBP or DBP > 90th percentile or not); and gender (male , female).

The child-parent dyad is randomized after all baseline measurements are completed: confirmation of BMI confirmed at ≥ 85th percentile; completion of baseline anthropometrics, blood pressure, questionnaires (other than those declined for personal reasons), accelerometry for a minimum of four valid days, a minimum of two dietary recall interviews (2 weekdays or 1 weekend, 1 weekday), and fasting blood tests (unless staff unable to draw blood) within 37 days of baseline visit. Data collectors are kept blinded to participants' group assignments at the time of randomization and at all data collection visits.

Treatment Interventions

Family-level Interventions

The IMPACT study tests two innovative family-focused experimental interventions, HealthyCHANGE and SystemCHANGE. Participants in both of these intervention arms receive comparable information regarding diet (DASH diet), physical activity, sleep, and stress management, but differ in the behavior change approaches taught. The common features of the two intervention are addressed first. Both the HealthyCHANGE and SystemCHANGE have equal time exposure; there are 25 face-to-face small group sessions in year 1, 12 contacts in year 2 (6 face-to-face, 6 phone) and 12 contacts in year 3 (4 face-to-face, 8 phone). The respective interventions are each delivered in small groups of ∼15 children, each with at least one family member. Each group is led by two interventionists trained in the respective intervention protocol. Interventionists are drawn from the community and predominately consist of middle school teachers and recreation center counselors who work with the IMPACT study as a second job. There are equal numbers of male and female interventionists, and all intervention sessions are led by at least one interventionist of minority race.

The child is weighed privately on a calibrated scale at each group session. Mate-rials/activities addressing developmentally- and culturally-appropriate diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management techniques for children are provided. The sessions are interactive and, in addition to the didactic content taught in the group sessions, include activities such as cooking classes, guest chefs, ethnic dancing, yoga, image consultants, field trips to inner-city grocery stores, and creation of photo and video presentations on healthy living by the children. In both interventions, parents and children are sometimes separated in the group sessions to receive different content/activities. For example, parents are separated from the child participants for discussions about parenting and discipline methods, whereas the children may be in the next room learning about how to manage bullying (common in children who are obese). Incentives provided for class attendance include a small gift take-away each session (e.g., gloves, sugar-free gum, key chain), and periodic raffles for larger gifts (e.g., X-Box, iPads). Data from our pilot study regarding participant preferences informed the selection of the type of activities included in the final intervention protocols, such as the rock wall climbing experience, image consultants, and ethnic dancing.

The HealthyCHANGE Intervention

The HealthyChange intervention is a family-based weight management program based in cognitive-behavioral theory with elements of motivational interviewing (MI). This intervention is a modification of a hospital-sponsored program previously developed by members of the study team. In HealthyCHANGE, a set of cognitive-behavioral/MI-consistent strategies are taught to promote health behavior change. Children and their parents are taught to assess their value systems regarding the target behaviors (diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management) and their ability to meet their short- and intermediate-term goals regarding weight management. Approaches to enhancing diet and exercise self-efficacy, problem-solving abilities, and relapse prevention skills are introduced. Family communication strategies are taught and reinforced throughout the sessions to support the positive enactment of home-based behaviors. The interventionists employ MI-consistent techniques in the sessions, including asking open-ended questions, reflective listening, and making affirmations and summary statements. MI also is used to identify any barriers to children completing activity and diet logs, with parental assistance as needed. When reviewing these logs at each session, children and parents are asked to identify areas in which to improve diet, activity, sleep, and stress management and ideas of possible solutions targeting these areas. If needed, they are assisted to problem solve any barriers they anticipate in implementing these solutions. We also provide tools for evaluating current behaviors, such as daily monitoring and setting realistic small-increment goals to improve their children's health-related behaviors, and practicing positive parenting strategies using at-home behavioral assignments. Cognitive-be-havioral skill development is included in each session, beginning with weekly self-monitoring by the child.

The SystemCHANGE Intervention

We are also testing a unique intervention, SystemCHANGE, that the authors have previously developed and was shown effective to change lifestyle behaviors in adults following cardiac events58, 59 and in persons with HIV.60 This study is the first application of SystemCHANGE for children's weight management. The SystemCHANGE intervention is based on system process improvement theory61, 62 and focuses on redesign of the activities in a family's daily routines related to home, school, and work to support positive behavior changes. In the SystemCHANGE intervention, families are taught how to modify their daily routine using a series of small, family-designed experiments. The goal is to produce new routines that support (or even assure) desired behavior change, reducing the need to rely on memory, self-control, personal effort, or motivation. In other words, when environmental routines are designed to promote healthier behavior choices, one is less dependent on personal levels of motivation and more likely to succeed despite wavering motivation. SystemCHANGE proposes that behavior change is best accomplished by identifying a measurable goal, examining the system processes surrounding attainment of that goal, listing several ideas about how best to improve the system, engaging in a series of experiments to test the best ideas to improve the process, implementing the most successful ideas based on data from the experiments, and monitoring the system to hold the gains. Participants develop and use a set of skills and tools to explore the interdependencies of their daily routines with others in their life and engage those individuals in redesigning the routines to promote healthier lifestyle choices. A number of process improvement techniques are used, including flow charting daily routines, fishbone diagrams to identify a range of system cause and effects on the desired behavior change, selecting systems-oriented vs. individual motivation-oriented solutions for change, using cycles of small experiments to test ideas for change, tracking objective data about cause and effect on behavior through the use of Cause and Effect diaries, and developing and maintaining a family storyboard describing the change process. All the materials have been adapted for age and cultural appropriateness based on the results of a series of focus groups held with children (n= 45) during the formative work stage of this project. These children provided suggestions regarding design of the materials to be used in the behavioral intervention groups, including suggestions on how to increase their attractiveness, ease of use and understandability.

Distinguishing features between the HealthyCHANGE and SystemCHANGE Interventions

The IMPACT project assesses the effect of two theoretically-different behavior change approaches. Both approaches - HealthyCHANGE and SystemCHANGE – involve distinctly different theoretical bases, overall focus, approach, process, and tools (see Table 1 below). The distinctions between the two interventions are driven by the differences in the conceptual models on which the interventions are built. The SystemCHANGE intervention is based on a socio-ecological model using Process Improvement strategies whereby emphasis is placed on changing the immediate environment (daily routines) of the individual that supports the practice of a particular habit. These process improvement strategies include use of a series of small family-designed experiments to test the effects of making small changes in their daily routines (habits). In contrast, the HealthyCHANGE intervention is based on a cognitive-behavioral model in which emphasis is placed on changing a person's viewpoint of a situation and to adjust behavior in line with a particular goal (changing health beliefs, increasing motivation, increasing problem-solving abilities to remove barriers and provide incentives). Although problem-solving ability is an important feature of both interventions, the SystemCHANGE intervention focuses on changing the systems in a person's daily routine using the trial-and-error approach of small family-designed experiments, whereas HealthyCHANGE uses a more traditional model of problem solving that targets motivation and overcoming barriers. Both of the IMPACT study interventions contain features consistent with other successful childhood obesity interventions,8, 21-23 including being family-focused, delivered using an intensive phase followed by a maintenance phase, and having both and education and behavioral components. However, the IMPACT study interventions build on successful current interventions by having both a family and a community component and a long structured coaching maintenance period (two years).

Table 1. Comparison of the two behavioral interventions.

| HealthyCHANGE | SystemCHANGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. Theoretical Basis | Cognitive-behavioral skill building | Ecological and Personal Process Improvement |

| II. Overall Focus | Build skills and increase intrinsic motivation | System re-design of the family environment/daily routines |

| III. Approach |

|

|

| IV. Processes/Tools | ||

| Education re: diet, physical activity, sleep & stress mgt | Y* | Y |

| Monitor Behavior | ||

| • Food log • Physical activity log • Cause and effect |

Y Y N |

N N Y |

| Storyboards | N | Y |

| Fishbone diagrams | N | Y |

| Flowchart daily routines | N | Y |

| Select system ideas for change | N | Y |

| Family small experiments | N | Y |

| Problem-solve barriers | Y | N |

| Values clarification | Y | N |

| Positive self-talk | Y | N |

| Decisional balance | Y | N |

| Interest & confidence rulers | Y | N |

| Rewards/points for goal | Y | N |

Y = major component of intervention; N = not a major component of intervention

Diet, Physical Activity, Sleep and Stress Management Components of the HealthCHANGE and SystemCHANGE Interventions

Diet

All interventions use a DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension)-like diet that can reduce weight and BP.63-66 Interventions include detailed information about the recommended modified DASH-like diet, (8 servings of fruit or vegetables/d, 3 servings of low fat dairy/d, 5-7 servings lean protein daily, sodium ≤ 2300 mg/d, [standard recommendation for adolescents]), moderate reduction in calories (consistent with the recommendations of the Expert Committee),34 and an overall approach emphasizing “better foods and healthy choices.” Total recommended daily caloric intake is consistent with recommended degrees of BMI reduction,34 however, emphasis is placed on the primary goal of a healthy diet and healthy choices. 25, 35, 67-77

Physical activity

All behavioral interventions include approaches to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior. Physical activity includes two components - the structured, planned, activities that include sports and recreation (measured and recalled somewhat easily, and counting towards a weekly goal) and lifestyle activity that involves movement tied to one's daily routine (mowing grass, walking the dog) that may be more difficult to track by recall. The overall goal is to significantly increase each youth's physical activity level above baseline levels - including both structured and lifestyle activities. We expose the participants to various types of activity (including sedentary activity) while also teaching intensity and caloric expenditure.

Sleep management

Information provided on sleep management consists of a discussion of the recommended amount of sleep for this age group of children, the benefits of regular sleep (especially in regard to weight management), reducing use of electronic communication devices late at night, optimizing the sleep environment, and sleep hygiene tips.

Stress Management: Parents and children are separated for this discussion. A discussion of sources of stress from the children's or parent's perspective are sought and acknowledged. Physical and psychological symptoms of stress are discussed, and techniques for managing day-to-day stress, such as relaxation strategies, rest, and regular physical activity are provided.

Tailoring the Interventions using a Responsive Intervention Approach

We are employing a responsive intervention design78 to tailor our interventions to study participants. A responsive intervention (also referred to as an adaptive intervention) employs a set of tailoring variables and decision rules whereby an intervention is modified in response to characteristics of the individual participant or the environment in order to produce optimal outcomes for each participant.79 This approach acknowledges that the varying intervention needs of individuals may not be met by using a single uniform composition and dose. This form of tailoring differs from the use of clinical judgment for tailoring at the time of delivery of an intervention in that in the responsive intervention design, explicit decision rules are developed a priori that link characteristics of an individual or environment with specific level and types of program components.78 The primary aim is to maximize the strength of the intervention. This approach also allows greater efficiency in the use of study resources.

The IMPACT study team gave careful consideration to the selection of the tailoring variables to include in our responsive intervention protocol. This involved reviewing the conceptual model underlying our two behavioral interventions and including the hypothesized mediating and moderating variables. This understanding of the pathways and relations of the study variables assisted the team to consider how the intervention components might differently affect any given child. The final variables selected for the responsive intervention and their thresholds were selected based on data from our year-long pilot study. Next, protocols describing the participant-specific modifications to be made to the behavioral interventions are based on baseline, process, or intermediate outcome measures taken on participants over the course of the study. Variables on which we tailor are: levels of binge eating, baseline obesity status, level of parent/family involvement, and excessive weight gain. Examples of the responsive intervention modifications in the IMPACT study are: the addition of a specified number of personal counseling sessions with a child, specific outreach effort to parents/family, and retraining a child in the use of a particular behavior change tool/skill. Modifications to the standard protocols are specific in regard to time exposure and procedures for delivery.

Control Intervention

In contrast to the intervention treatment arms, children and their parent(s)/guardian in the brief education-only control group (Tools4Change) receive three contacts with study personnel each study year. First, participants receive one 60-minute individual, face-to-face counseling session at initiation of the study with a dietitian who is also trained in recommendations for exercise and sedentary behavior. The dietitian provides individual Dash diet meal plan information and reviews food groups and serving sizes with the child and parent in this counseling session. The family is given several handouts and booklets (5th-6th grade reading level) that provide written information about the DASH diet and activity guidelines. In addition to the annual clinical assessment received by all study participants, they receive two other contacts with study personnel in each of the study years, a social phone call reminding them of their participation in the study and a social gathering event (i.e., picnic, ball game) of small groups of families in the control group. These contacts are primarily to enhance control group participant retention over the 3-year study period.

School-Level Intervention: Enriched School Environments

In any given year of the project, approximately half of the participants will be attending a local public school that participates in an innovative community-sponsored fitness program run by the YMCA, called the We Run This City Youth Marathon Program (WRTC).80 WRTC is a school-based program that encourages physical activity in middle school students by building their capacity to participate (walking or running) in a segment of the Rite Aid Cleveland Marathon. All K-8 schools in the large urban school district are invited to join; approximately 30-35 of the 68 K-8 schools do so each year.

Each January, participating schools register a “team” to participate in the WRTC program. IMPACT study participants enrolled in a school with a WRTC team will be encouraged to join their school's team. Each team is led by a “coach,” typically a physical education teacher, and teams are comprised of 6-8th graders, varying in size from 10 to 50 students, depending upon the size of the school. WRTC is not a program specifically for athletes; rather it was originally designed to fill the gaps in physical education within the school curriculum. Typically, 30-40% of the WRTC participants are overweight or obese and most have never run or walked for fitness in the past. The teams are created each December-January, and training begins at the end of January. All WRTC participants are encouraged to log at least 25 miles of walking/jogging prior to the mid-May marathon and then finish their training with one of three options: (1) run the remaining 1.2 miles, completing a total of 26.2 miles (hence, the “marathon” by combining training miles and race miles); (2) run/walk the 10k (6.2 miles); or (3) run the ½ Marathon (13.1 miles). We anticipate that the vast majority of IMPACT study participants to participate in the 1.2 mile event.

The IMPACT study supplements the WRTC teams and schools with additional programming and support through the study-supported Navigators. Navigators are masked to study enrollment and randomization assignment. For each of the WRTC schools, the Navigators work to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors among the entire student body with a health-oriented social marketing campaign that complements the materials that are distributed in both HealthyCHANGE and SystemCHANGE. In addition, the Navigators provide programmatic support during trainings, supporting IMPACT student participation and working to motivate study participants by modeling healthy behaviors. They also ensure that coaches complete the weekly training logs that document training dosage and intensity. Finally, the study provides training to the coaches on best practices for encouraging and motivating children who are overweight/obese for sustained participation in physical activity. Non-enriched school-community environments are schools from school districts that do not participate in the WRTC program and have none of these supplements to regular classroom-based health and physical education.

IMPACT study participants have the potential of participating in the WRTC program each year, for three years of the intervention. However, because both schools and students have the option to participate each year, and some students may change schools (i.e., from enriched to non-enriched or vice versa), exposure to the enriched school environment will vary across individuals and across the three years of the study. We assess exposure to the enriched school environment monthly throughout the three years (see Intervention Dose below).

Intervention Dose

Each participant in the intervention arms will receive 36 months of one of the two family-level interventions. SystemCHANGE and HealthyCHANGE participants will have intensive face-to-face group sessions at 2-week intervals over the first 12 months (25 sessions of 90 minutes in length), followed by rotating monthly group face-to-face meetings or phone calls for a further 24 months. Participant-level data are kept on intervention attendance and participation in all intervention components (i.e., group sessions, responsive intervention components, phone calls, social events, etc.) so that the exact dose received by each participant can be calculated.

Respondents have the potential of receiving up to three years of the school-community enrichment exposure. Due to the transient nature of an urban population and that each school's participation in the WRTC program may change from year to year, exposure to the school-level intervention will be assessed as an accumulative exposure, based on monthly status assessments. Each month, participants will be assigned a monthly “exposure score” using the following metric: (0) not in a WRTC school, (1) in a WRTC school but either no programming was conducted that month or the child did not participate (not enrolled in WRTC), (2) in a WRTC school and enrolled in the WRTC program. These monthly status scores will be summed for an annual exposure score. In addition, for those participants who are enrolled in the WRTC program, we will collect monthly training data that includes distance, time and effort.

Assessments and Measurements

Data are collected at one of two Clinical Research Units (CRU) at large hospital systems at baseline and at 12, 24, and 36 months following randomization. Informed consent is reviewed with parents; assent is also obtained from the child. Data are collected by trained and certified research study team members, assisted by CRU staff (nurses, dietitian, diet technicians). All data are collected with parent/guardian and child in private. Questionnaire and interview-based data are obtained by private interview and, for some questionnaires, by audioassisted survey software (Qualtrex). Data are entered directly into a laptop or iPad225.

Anthropometrics

Weight, height, waist circumference, and triceps skinfolds are measured for all index children, and weight and height are measured for adults in the household. Weight and height are measured with the participant in light clothing without shoes. Weight is measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using research precision grade and calibrated digital scales, and height is measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a free-standing or wall-mounted stadiometer. BMI (the primary outcome) is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Waist is measured to the nearest 0.1 cm just above the uppermost lateral border of the right ilium using a Gulick II tape measure, model 67020. The triceps skinfold is measured using a Lange skinfold caliper (or a Harpenden caliper if the measurement exceeds capacity of the Lange skinfold caliper) in the midline of the posterior aspect (back) of the arm, over the triceps muscle, at a point midway between the lateral projection of the acromion process of the scapula (shoulder blade) and the inferior margin (bottom) of the olecranon process of the ulna (elbow). Triceps skinfolds are measured to the nearest 0.1 mm. For quality control, ten percent (10%) of the anthropometric measurements are measured by two different data collectors.

Dietary Assessment

Dietary intakes are measured using 24-hour dietary recall interviews that are conducted on two weekdays and one weekend day using NDS-R software. Dietary recalls are collected in-person or over the telephone in English or Spanish. The Food Amounts Booklet is used by the respondent to assist in identifying portion sizes. To avoid collecting days with similar foods, recalls are not conducted on consecutive days. In addition, in order to capture variability of food supplies in the home, all three recalls do not occur within a seven-day period. The third recall is collected more than one week after the first recall. All three recalls are collected within 30 days. Full quality assurance checks are conducted on at least 10% of the dietary recalls according to NDS-R standard protocols.

Physical Activity

Accelerometry data are collected on all index children using the GT3X+ monitor. The GT3X+ monitor is worn on the right hip for seven complete days (including while sleeping and naptime) except during water activity (e.g., bathing, swimming, showering). The ActiGraph GT3x+ assesses acceleration in three individual orthogonal planes using a vertical axis, horizontal axis and a perpendicular axis. The GT3X+ is set to 40-Hertz frequency and the GT3X is set to 1-second epoch. The valid wear time criteria (minima) are 4 days (3 weekdays and 1 weekend day) of at least 6 hours of activity between 5:00am and 11:59pm.

Blood Pressure

An automated blood pressure measurement device (OMRON HEM-705-CPN Digital Blood Pressure Monitor) is used to measure systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse in all index children. The participant's arm circumference is measured to ensure the correct cuff size is used. Participants sit quietly for 4-5 minutes before the first measurement is taken, and seated, resting blood pressure and pulse are measured three times. The first reading is discarded, and the average of the second and third measurements is used in analysis. All readings are recorded to the nearest integer.

Biomedical Measures

Blood specimens are collected at baseline, 12 months and 36 months. All blood specimens are analyzed by the Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories (NWRL). The biomedical measures analyzed in the index child are Hemogloblin A1c (HbA1c), Glucose, Total Cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, Triglycerides, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Insulin and Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT). Index children are instructed to fast for at least 8 hours. A trained phlebotomist is responsible for blood collection and ascertaining fasting status of the index child.

Secondary Outcomes, Moderators and Mediators

As shown in our conceptual framework, our study also examines a comprehensive list of both mediators and moderators that are specific to the IMPACT study. First, the theoretical frameworks on which our two family-based interventions are based suggest a set of proposed mediators we will measure (child's self-efficacy, social support, motivation, and family problem-solving, systems thinking, self-regulation) that we hypothesize will influence the proximal outcomes of diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress, which in turn (also mediators themselves) will impact more distal, physiological outcomes (BMI, blood pressure, fitness levels, cardiovascular risk).

There is strong evidence identifying several behavioral, contextual, and environmental factors as critical underpinnings of adolescent obesity.34-45 Family, school, peers, community, and policy act together to provide the environmental contexts that shape children's energy intake and expenditure, which in turn influence the development of obesity and its co-morbidities. These factors are not only likely to have an independent impact on BMI outcomes, but also are likely to moderate the impact of the interventions themselves. These include: the family's socioeconomic status and demographic characteristics, personal characteristics of the child, parent/guardian, and family (including physiological and psychosocial characteristics), the child's physical and social environment (neighborhood, school, and family), and peer norms surrounding nutrition, physical activity and perceived environment. We posit that these factors may moderate the impact of the interventions on outcomes, as well as interventions on the program-specific mediators. Covariates deemed from the literature to be confounders also will be assessed.

With the exception of the environmental variables, all other mediators and moderators are collected during the clinical visit, either through the semi-structured interview, via the electronic-based surveys described above or through observation, as is the case with the shuttle run test used to assess fitness. To accommodate the sample being studied, the surveys are administered in both English and Spanish. All of the site-specific measures are included in Table 2.

Table 2. IMPACT Site Specific Mediators, Moderators and Secondary Outcomes.

| Construct | Tool | Reference | # items | Collected from? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Quality & Quantity | Sleep Evaluation Questions | Mindell & Owens, 200990 | 6 | P |

| Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale | LeBourgeois et al., 200591 | 28 | P | |

| Daytime Sleepiness Scale | Mindell & Owens, 200990; Farber, 200292 | 8 | P | |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Mindell & Owens, 200990; Farber, 200292 | 8 | P | |

| Self-efficacy for diet | Children's Self-Efficacy Survey | Sallis, 198793 | 15 | P,C |

| Self-efficacy for physical activity | Self-Efficacy Scale for Physical Activity Barriers | Saunders, 199794 | 4 | P,C |

| Family and friend social support for diet | Social Support and Eating Habits Survey | Sallis, 198793; scoring, 1996 | 20 | P,C |

| Family and friend social support for physical activity | Social Support and Exercise Survey | Sallis, 198793; scoring, 1996 | 10 | P,C |

| Motivation | Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire – autonomous regulation subscale | Williams95, 1996 | 6 | P,C |

| Systems Thinking | Systems Thinking Scale | Moore & Dolansky, 201096 | 20 | P,C |

| Self-Regulation | Index of Self-Regulation | Fluery, 199897 | 7 | P,C |

| Perceived Stress | Perceived Stress Scale | Cohen, 198398 | 10 | C |

| The Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents | Sheras, 199899 | 34 | P | |

| Self-esteem | Modified Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory (from ADD Health) | Rosenberg, 1965100 | 6 | C |

| Depressive symptoms | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children | Weissman, 1980101 | 20 | C |

| Eating disorder symptoms | Youth Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire | Goldschmidt, 2007102 | 3 | C |

| Family functioning. | Family Assessment Device (general functioning subscale) | Epstein, 1983103 | 12 | P |

| Psychological functioning | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | Radloff, 1977104 | 20 | P,C |

| Social problems | Child Behavior Checklist – social problems subscale | Achenbach, 1991105 | 6 | P |

| Family rituals at mealtime | Family Ritual Questionnaire – dinnertime subscale | Fiese, 1993106 | 7 | P,C |

| Parental beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding feeding | The Child Feeding Questionnaire | Birch, 2001107 | 31 | P |

| Food in home | Active Where? Survey – Food scale | Kerr, 2006108 | 16 | P,C |

| Availability of equipment in home | Brief scale for sedentary activity equipment in the home | Rosenberg, 2010109 | 11 | P,C |

| Brief scale for physical activity equipment in the home | Rosenberg, 2010109 | 14 | P,C | |

| Transportation to school | Active Where? Survey – Physical activity and school scale | Durant, 2009110, 111 | 6 | P,C |

| Rules about eating | Active Where? Survey – Rules for eating scale | Kerr, 2006108 | 12 | P,C |

| Parental monitoring | Parental Monitoring Scale | Li, Stanton & Feigelman, 2000111 | 5 | P,C |

| Rules for Screen Time | Active Where? Survey – Rules for TV | Ramirez, 2010112 | 8 | P,C |

Environmental Assessments

A secondary aim of the study is to examine the moderating influence of environmental factors (the environment around the home and the school and community environments) on the impact of the child-family interventions on BMI. To do so, a number of primary and secondary sources of school and community level data will be used to develop algorithms for creating child-specific environmental profiles based on the child's neighborhood socioeconomic status (e.g., income, female-headed households, education levels); school and neighborhood food environment (e.g., fast food to grocery/market ratio, classroom snacking policy, average fruit & vegetable consumption, and physical activity levels of school peers); safety (crime data and perceptions); and the built environment impacting physical activity (park, recreation centers, green space). In addition, school-specific Youth Risk Behavior Survey data will be used to summarize the normative peer influences for each child.

Within 60 days of randomization a Neighborhood Attribute Inventory (NAI) is conducted on the street segment in front of each participant's home. The NAI is a modified version of the street audit developed by Caughy and colleagues,81 that assesses attributes related to physical and neighborhood surroundings that might influence behavior change, representing four categories of neighborhood attributes: neighborhood physical conditions; social interactions; nonresidential land use (commercial property); and public, residential and nonresidential space. The inventory is recollected annually or if a participant moves.

The School Food and Beverage Audit (SFBA) Tool is used to assess the school food environment. The SFBA is a modified version of the food and beverage marketing and advertising tools used by Samuels and Associates to assess the availability of food and beverage and healthy or un-healthy marketing on school grounds.82 The tool also assesses discrepancies in the school menus and what is actually served in the cafeterias, locations and availability of vending machines, the quality and availability of school dining facilities, and school stores when applicable. The Neighborhood Food Environment Database (NFED) is being developed in conjunction with the Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods (PRCHN) to allow us to create student-centric scores for analysis. Using Arc-GIS,83 a geographical information system software package, we will calculate a 0.25 and 0.75 mile Euclidean buffer around a participant's home and school in order to conceptualize the immediate surroundings (0.25 mile) and neighborhood food retail environments (0.75 mile buffer) respectively. The number of food retail establishments that fall within these buffers will be enumerated and used to calculate densities of facilities within a given neighborhood.

We also will draw objective social environment data from the Northeast Ohio Community and Neighborhood Data for Organizing (NEO-CANDO),84 a free and publicly accessible social and economic data system developed by the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development, housed at Case Western Reserve University. NEO-CANDO provides data on indicators including poverty, education, employment, public assistance, and crime at the block and census-tract level. This will allow for social and economic indices to be created for each participant based on where they live.

Finally, the local Youth Risk Behavior Survey is used to capture school-specific normative data on physical activity, nutrition, and student perception of school policies in these areas. The PRCHN administers the survey in all K-8 schools within the Cleveland Metropolitan School District and all charter schools who participate in the screening program, every other year. The middle school survey, which serves as the baseline for this study, was administered in the fall of 2012. This full district approach allows us access to school-specific normative data on all children in the study, even if they move from their original school.

Statistical Analyses

Our primary analysis assesses the value of our interventions (SystemCHANGE [SC] and HealthyCHANGE [HC]) as compared to education-only control on change in BMI across the three-year study period. Our hypothesis is that both SC and HC will have greater impact than education alone on change in BMI. BMI values are measured at baseline, 12, 24, and 36 months. The statistical model for our primary outcome (BMI slope for a given subject) is a linear model incorporating the subject's baseline BMI and indicators for SC and HC, across the 360 subjects who provided baseline BMI data and were randomized to a study arm. Our derived primary outcome - BMI slope across the study period, will be imputed for patients who fail to complete all post-baseline BMI assessments, and otherwise calculated in terms of change per annum across available BMI measurements. Using our linear model, our primary comparison is an F test of the null hypothesis of zero coefficients for the effects of both the SC and HC indicators. We will account for what we anticipate to be modest clustering within intervention small groups and within schools, through modeling the small groups and schools as levels of nested random effects.

Treatment Effects

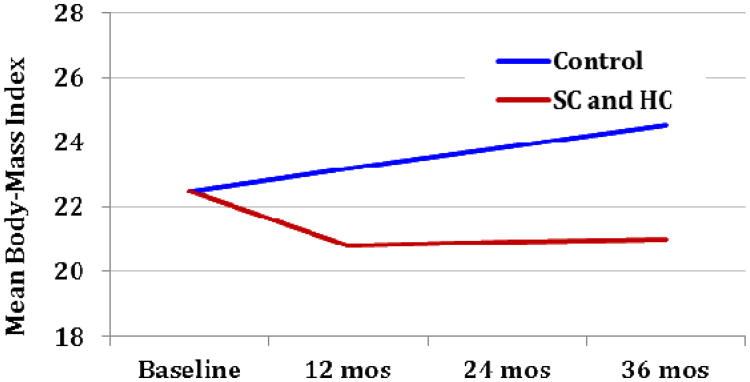

We expect a non-linear shape to the association of BMI with time in our treatment groups, with a larger effect at the start of the study (decline in BMI of about 1.8 kg/m2 in our HC and SC intervention groups in year 1), and some reduction in the size of this effect (perhaps even a slight rise in BMI as compared to baseline) in years 2 and 3 (see Figure 2).The evidence to support an expectation of a non-linear effect, leveling off after year 1, is modest and primarily based on the work of Savoye et al.85

Figure 2. Änticipated Trajectories.

We anticipate a mean BMI near 21 for our HC and SC patients at the year 3 measurement point, with a larger standard deviation than in our control group. While we expect the largest effect to occur in the first year, the trend towards rising BMIs in the control group suggests that the largest difference in raw BMI (not change in BMI) between groups will be at 36 months. Our hypothesized change in BMI is clinically significant in that modest weight decreases of this magnitude in children have been shown to be associated with decreases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and fasting insulin.85, 86

Detectable Difference, Sample Size and Power

Our planned sample size should be adequate to detect differences in BMI slopes substantially smaller than those described in Figure 2. We describe our desired detectable effect size in terms of an incremental R2 value attributable jointly to the indicators for SC/HC (as compared to control) describing the variation in BMI slopes independent of baseline BMI. Assuming that 20% of the 360 participants who complete baseline and are randomized to a study arm do not complete a single post-baseline BMI assessment over the three-year study window, we investigated effect sizes as small as an incremental R2 of 5%. Using the pwr library in the R statistical software language, we concluded that (without imputation) an effective sample size of 288 subjects - 96 per arm - yields just over 94% power to detect an R2 = 5% effect. After imputation, we retain at least 90% power to detect incremental effects of group as small as R2 = 4.2%

Secondary Analyses

We also will conduct mediator and moderator analyses87, 88 to test our full model shown in Figure 1. These include testing the moderating effect of the school-level interventions, assessing the effect of the hypothesized mechanisms of our interventions (mediators), and evaluating intervention effects on intermediate and secondary outcomes.

Discussion

Most trials of interventions to prevent89 or treat21 childhood obesity have shown limited effectiveness. The IMPACT study design not only draws upon recent literature regarding best practices to achieve behavior change for weight management in children, but also accounts for the unique circumstances of our population, making the IMPACT study both an effectiveness and an efficacy trial. Consistent with recent literature,47-49 we designed a multi-level, multi-component interventional approach. Two critical levels of intervention (family-level and school-level) are utilized. We also leverage an existing program that assesses BMI and BP in Cleveland schools, providing a community-wide approach to identify at-risk children and employ an innovative and successful YMCA-sponsored school program that encourages physical activity in urban youth. Both the family interventions and school interventions consist of several components and are delivered in an iterative format – the children have multiple opportunities to receive every component.

We acknowledge that the inclusion of only low-income urban families from an urban environment limits potential generalization of the findings to other populations. However, we have built several features into the IMPACT project that we believe will potentially improve its effectiveness over past studies of obesity management in this vulnerable population. Although some of these features are unique, most are harvested from the literature; it is their combination in sufficient dose in the IMPACT study protocol that we believe increases our ability to achieve a positive effect on weight management in these disadvantaged, high-risk children. These IMPACT features are: (1) strong community engagement (Community Advisory Board, Cleveland Public Schools involvement, YMCA programming); (2) extensive formative work (separate focus groups with children and parents, a one-year pilot test of the family-level interventions and study recruitment and measurement procedures); (3)the use of a responsive intervention to allow individualization, yet future replication, of the interventions; (4) test of a novel approach to behavior change (SystemCHANGE); and (5) strong consideration of environmental variables (home, school and neighborhood food environments, peer norms surrounding nutrition and physical activity).

In addition to generating evidence about the efficacy of the interventions on weight management, the IMPACT study also is designed to provide several unique contributions to the field of behavioral science regarding weight management, including testing two-theoretically different interventions (comparing SystemCHANGE with a gold standard, traditional cognitive-behavioral approach and assessing the mechanisms of each); the inclusion of blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors as secondary outcomes (allowing us to track changes in these important health indices in this high-risk, vulnerable youth population), and our precise measurements over time of a vast array of environmental factors potentially affecting weight management in this population. We also have an analytic design that will allow us to assess for the possible potentiating effect of the school intervention on the family-level interventions. This multi-level approach takes into account the numerous factors contributing to childhood obesity and the probable complex interventions needed to help children obtain and maintain healthy weights.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number HL103622. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shirley M. Moore, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH, USA 44106-4904.

Elaine A. Borawski, Email: exb11@case.edu, Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Nutrition, Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44106.

Leona Cuttler, Email: leona.cuttler@case.edu, Director, The Center for Child Health and Policy at Rainbow, Chief, Pediatric Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106.

Carolyn E. Ievers-Landis, Email: carolyn.landis@uhhospitals.org, Division of Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics & Psychology, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, 10524 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH, USA 441060-6038.

Thomas Love, Email: Thomas.Love@case.edu, Director, Biostatistics & Evaluation, Center for Health Care Research & Policy, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, 2500 MetroHealth Dr, Cleveland OH 44109-1998.

Reference List

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003-2006. Jama. 2008;299(20):2401–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(13):869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature Preventive medicine. 1993;22(2):167–177. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels SR, Jacobson MS, McCrindle BW, Eckel RH, Sanner BM. American Heart Association Childhood Obesity Research Summit Executive Summary. Circulation. 2009;119(15):2114–2123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obarzanek E, Pratt CA. Girls health Enrichment Multi-site Studies (GEMS): new approaches to obesity prevention among young African-American girls. Ethnicity & disease. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year follow-up of behavioral, family-based treatment for obese children. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(19):2519–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Beecher MD, Roemmich JN. Increasing Healthy Eating vs. Reducing High Energy-dense Foods to Treat Pediatric Obesity. Obesity. 2008;16(2):318–326. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig DS, Ebbeling CB. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in children. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(12):1427–1430. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson TN, Kraemer HC, Matheson DM, et al. Stanford GEMS phase 2 obesity prevention trial for low-income African-American girls: design and sample baseline characteristics. Contemporary clinical trials. 2008;29(1):56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanovski JA. Intensive therapies for pediatric obesity. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2001;48(4):1041–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(8):591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanovski SZ. A practical approach to treatment of the obese patient. Archives of family medicine. 1993;2(3):309. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inge TH, Krebs NF, Garcia VF, et al. Bariatric surgery for severely overweight adolescents: concerns and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):217–223. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inge TH, Xanthakos SA, Zeller MH. Bariatric surgery for pediatric extreme obesity: now or later? International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uli N, Sundararajan S, Cuttler L. Treatment of childhood obesity. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2008;15(1):37–47. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f41d6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkowitz RI, Fujioka K, Daniels SR, et al. Effects of Sibutramine Treatment in Obese Adolescents: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(2):81–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Tershakovec AM, Cronquist JL. Behavior therapy and sibutramine for the treatment of adolescent obesity. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(14):1805–1812. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Saelens BE, et al. Efficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(14):1661–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilfley DE, Tibbs TL, Van Buren DJ, Reach KP, Walker MS, Epstein LH. Lifestyle interventions in the treatment of childhood overweight: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. 2007;26(5):521–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD001872. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001872.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christison A, Khan HA. Exergaming for Health A Community-Based Pediatric Weight Management Program Using Active Video Gaming. Clinical pediatrics. 2012;51(4):382–388. doi: 10.1177/0009922811429480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jelalian E, Mehlenbeck R, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Birmaher V, Wing RR. ‘Adventure therapy’ combined with cognitive-behavioral treatment for overweight adolescents. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;30(1):31–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute NIoH. Working Group Report on Future Research Directions in Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):1175–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. 2005;111(15):1999–2012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F. High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1488–1496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuttler L, Whittaker JL, Kodish ED. Pediatric obesity policy: the danger of skepticism. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2003;157(8):722. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. The Future of Children. 2006;16(1):47–67. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homer C, Simpson LA. Childhood Obesity: What's Health Care Policy Got To Do With It? Health Affairs. 2007;26(2):441–444. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sørensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(23):2329–2337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson P, Pletcher MJ, Lightwood J, Goldman L. Adolescent overweight and future adult coronary heart disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(23):2371–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5):w822–w831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barlow SE. Expert Committee Recommendations Regarding the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity: Summary Report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):S166. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. pediatrics aappublications org/content/120/Supplement_4 S 2007; 164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ello-Martin JA, Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ. The influence of food portion size and energy density on energy intake: implications for weight management. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82(1):236S–241S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.236S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li F, Harmer P, Cardinal BJ, Bosworth M, Johnson-Shelton D. Obesity and the built environment: does the density of neighborhood fast-food outlets matter? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23(3):203–209. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071214133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galvez MP, Hong L, Choi E, Liao L, Godbold J, Brenner B. Childhood obesity and neighborhood food-store availability in an inner-city community. Academic pediatrics. 2009;9(5):339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Berkey CS, et al. Family dinner and adolescent overweight. Obesity Research. 2005;13(5):900–906. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casey PH, Szeto K, Lensing S, Bogle M, Weber J. Children in food-insufficient, low-income families: prevalence, health, and nutrition status. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2001;155(4):508. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pate RR, Davis MG, Robinson TN, Stone EJ, McKenzie TL, Young JC. Promoting physical activity in children and youth a leadership role for schools: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee) in collaboration with the councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation. 2006;114(11):1214–1224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koplan JP, Dietz WH. Caloric imbalance and public health policy. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(16):1579–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burdette HL, Wadden TA, Whitaker RC. Neighborhood safety, collective efficacy, and obesity in women with young children. Obesity. 2006;14(3):518–525. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1650–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiologic reviews. 2009;31(1):7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lumeng JC, Appugliese D, Cabral HJ, Bradley RH, Zuckerman B. Neighborhood safety and overweight status in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(1):25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A, et al. Influence of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture on Childhood Obesity: Implications for Prevention and Treatment A consensus statement of Shaping America's Health and the Obesity Society. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2211–2221. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diez Roux AV. Integrating social and biologic factors in health research: a systems view. Annals of epidemiology. 2007;17(7):569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosso IM, Young AD, Femia LA, Yurgelung-Todd DA. Cognitive and emotional components of frontal lobe functioning in childhood and adolescence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021(1):355–362. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoelscher DM, Evans A, Parcel G, Kelder SH. Designing effective nutrition interventions for adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102(3):S52–S63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang TT, Esposito L, Fisher JO, Mennella JA, Hoelscher DM. Peer Reviewed: Developmental Perspectives on Nutrition and Obesity From Gestation to Adolescence. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2009;6(3) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cuttler L, Singer M, Simpson L, Gallan A, Nevar A, Silvers JB. Obesity in children and families across Ohio. Ohio Family Health Survey. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods. 2010 Cuyahoga County Middle School Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) Report. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moore SM. Scientific reasons for including persons with disabilities in clinical and translational diabetes research. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2012 Apr 28;2012:236–241. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conlon M, Anderson GC. Three methods of random assignment: comparison of balance achieved on potentially confounding variables. Nurs Res. 1990;39(6):376–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore SM, Charvat JM, Alemi F, Gordon N, Ribisl P, Rocco M. Improving Lifestyle Exercise in Cardiac Patients: Results of the SystemCHANGE Trial. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 530 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19106-3621 USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moore SM, Charvat JM. SystemCHANGE: Results of a Lifestyle Exercise Intervention Trial. Springer; 233 Spring St, New York, NY 10013 USA: 2012. p. S79. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Webel AR, Moore SM, Hanson JE, Patel SR, Schmotzer B, Salata RA. Improving sleep hygiene behavior in adults living with HIV/AIDS: a randomized control pilot study of the SystemCHANGE intervention. Applied Nursing Research. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alemi F, Neuhauser D, Ardito S, et al. Continuous self-improvement: systems thinking in a personal context. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26(2):74–86. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(00)26006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langley G, Nolan K, Nolan T. The Foundation of Improvement. Quality Progress. 1994:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Appel LJ, Brands MW, Daniels SR, Karanja N, Elmer PJ, Sacks FM. Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2006;47(2):296–308. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000202568.01167.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Couch SC, Saelens BE, Levin L, Dart K, Falciglia G, Daniels SR. The efficacy of a clinic-based behavioral nutrition intervention emphasizing a DASH-type diet for adolescents with elevated blood pressure. J Pediatr. 2008;152(4):494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(7):485–495. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daniels SR, Khoury PR, Morrison JA. The utility of body mass index as a measure of body fatness in children and adolescents: differences by race and gender. Pediatrics. 1997;99(6):804–807. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Falkner B, Sherif K, Michel S, Kushner H. Dietary nutrients and blood pressure in urban minority adolescents at risk for hypertension. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2000;154(9):918. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.9.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pietrobelli A, Faith MS, Allison DB, Gallagher D, Chiumello G, Heymsfield SB. Body mass index as a measure of adiposity among children and adolescents: a validation study. The Journal of pediatrics. 1998;132(2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Dolan LM, Daniels SR, Standiford D, Khoury PR, Zeitler P. Increased incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus among adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics. 1996;128(5):608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)80124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scott CR, Smith JM, Cradock MM, Pihoker C. Characteristics of youth-onset noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus at diagnosis. Pediatrics. 1997;100(1):84–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dwyer JT, Stone EJ, Yang M, et al. Predictors of overweight and overfatness in a multiethnic pediatric population. Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health Collaborative Research Group. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1998;67(4):602–610. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.4.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teixeira PJ, Sardinha LB, Going SB, Lohman TG. Total and regional fat and serum cardiovascular disease risk factors in lean and obese children and adolescents. Obesity Research. 2001;9(8):432–442. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(23):1650–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGill HC, McMahan CA, Malcom GT, Oalmann MC, Strong JP. Relation of glycohemoglobin and adiposity to atherosclerosis in youth. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1995;15(4):431–440. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berkey CS, Colditz GA. Adiposity in Adolescents: Change in Actual BMI Works Better Than Change in BMI z Score for Longitudinal Studies. Annals of epidemiology. 2007;17(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, Heo M. What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI%, BMI z-score or BMI centile? European journal of clinical nutrition. 2005;59(3):419–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. Advance data. 314. 2000. CDC growth charts: United States; p. 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murphy SA, Collins LM, Rush AJ. Customizing treatment to the patient: adaptive treatment strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2):S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004;5(3):185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borawski E, Kofron R, Danosky L. “We Run This City” Youth Marathon Program 2010 Program Evaluation Report. 2010 [Google Scholar]