Abstract

Following nitric oxide (nitrogen monoxide) and carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide (or its newer systematic name sulfane, H2S) became the third small molecule that can be both toxic and beneficial depending on the concentration. In spite of its impressive therapeutic potential, the underlying mechanisms for its beneficial effects remain unclear. Any novel mechanism has to obey fundamental chemical principles. H2S chemistry was studied long before its biological relevance was discovered, however, with a few exceptions, these past works have received relatively little attention in the path of exploring the mechanistic conundrum of H2S biological functions. This review calls attention to the basic physical and chemical properties of H2S, focuses on the chemistry between H2S and its three potential biological targets: oxidants, metals and thiol derivatives, discusses the applications of these basics into H2S biology and methodology, and introduces the standard terminology to this youthful field.

Keywords: hydrogen sulfide, sulfane, sulfhydration, oxidants, metal, transsulfuration

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (or its newer systematic name sulfane [1], H2S) had been conventionally considered as a toxic molecule until sixteen years ago when Abe and Kimura first suggested its physiological function in the nervous system [2]. In 2008, Yang et al. developed mice deficient in the H2S generating enzyme cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) and discovered the development of hypertension in these CSE knockouts [3]. Their study further confirmed the endogenous generation of H2S and its physiological relevance. Since then, H2S has been found to play a variety of roles in mammals ([4–8] and the accompanying review in this issue) and more intriguingly, is considered as the third “gasotransmitter”1 after nitric oxide (nitrogen monoxide, •NO) and carbon monoxide [9–14]. In contrast to the tremendous number of reports on its potential therapeutic effects [13,15–17], the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. H2S biochemistry has been reviewed, suggesting mechanisms including reducing oxidative stress and protein post-translational modification [18–20]. However, the chemistry defining the interactions between H2S and its direct targets has been largely overlooked. Here we provide an overview of H2S chemistry that is biologically relevant but has been studied mostly from other aspects, and discuss applications in H2S biochemistry and biology. Since there has recently been interest in the similarities and interactions between H2S and •NO biology [21–27], we categorize H2S chemistry based on the three potential targets that H2S may share with •NO, oxidants, metals and thiol (RSH) derivatives. The goal is to reemphasize the importance of basic chemistry on the road of biological adventures.

2. Basic physical and chemical properties

Under ambient temperature and pressure, H2S is a colorless gas with an odor of rotten eggs. It is flammable and poisonous in high concentrations. Acute exposure to 500 ppm can cause death [28]. In this regard, caution should be used for handling [29]. H2S is soluble in water, its solubility has been reported to be about 80 mM at 37 °C [19], 100 mM in water at 25 °C [30], 122 mM in water at 20 °C [31] and up to ~ 117 mM (condition unspecified) [17]. The differences are apparently due to the experimental conditions including pressure, temperature and the composition of the solution. On the other hand, aqueous H2S is volatile. In other words, H2S always equilibrates between the gas phase and the aqueous phase (first equilibrium of eq. 1). Its properties of gas-aqueous distribution including Henry’s Law coefficient have been studied [32]. H2S is lipophilic [14,31] and can diffuse through membranes without facilitation of membrane channels (lipid bilayer permeability PM ≥ 0.5 ± 0.4 cm/s) [33].

| (1) |

H2S is a weak acid, it equilibrates with its anions HS− and S2− in aqueous solution (second and third equilibria of eq. 1). Its pKa values appear frequently in publications, particularly review articles, however, the original research reports are rarely cited. Here are mentioned a few good sources. A survey of publications prior to 1970 showed that the reported pKa1 values varied from 6.97 to 7.06 at 25 °C, and pKa2 from 12.35 to 15 [34]. Based on that survey the pKa1 value of 7.02 was suggested [35]. Thereafter, a similar range of pKa2 values (12.20~15.00 at 25 °C) has been reported [36], whereas higher values (17.1 ± 0.2 at room temperature [37], > 17.3 ± 0.1 at 25 °C [38], 19 at 25 °C [39] and 19 ± 2 [40]) have also been reported. Assuming a pKa1 value of 7, it can be calculated that 28% of the total hydrogen sulfide in a pH 7.4 solution exists as H2S, whereas 72% is in the form of HS−. The high pKa2 value indicates that S2− is negligible in the solution. The pKa value of a compound depends on conditions including temperature and the solution composition. Millero and Hershey reviewed both thermodynamics and kinetics studies on aqueous H2S, and derived equations for the calculation of both pKa and the solubility of H2S under certain pressure, temperature and composition of the solution [41,42]. Using precise pKa values under the exact experimental conditions is important for the calculation of H2S concentration. It has been shown that at physiological pH the concentration of H2S (or H2S(aq)) at 20 °C (pKa1 6.98) can be twice as much as that at 37 ° C (pKa1 6.76) (Figure 3 in [29]).

Practically, the three equilibria in eq. 1 represent the real dynamics of the H2S solution. One can easily predict that in an open system, according to Le Châtelier’s Principle the equilibria will continuously shift to the left, in the direction of forming H2S(aq) which then escapes from solution. It has been reported that half of H2S can be lost from solution in five minutes in cell culture wells, three minutes in a bubbled tissue bath and an even shorter time in the Langendorff heart apparatus [43]. This fact should be taken into consideration for the actual H2S concentration in an experimental system containing headspace, which has been utilized in most of the studies on H2S. This may also explain to some extent the remarkable variations in the reported H2S concentrations in tissues and plasma [44–46]. Moreover, one should also be aware that based on eq. 1, the leftward equilibrium shift could cause not only a tremendous decrease in H2S concentration, but also a considerable increase of the solution pH. Eq. 1 is also the basis of the application of H2S gas or inorganic metallic sulfide such as sodium sulfide (Na2S) and sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) as H2S sources in solution. Caution should be taken since an unbuffered stock solution from H2S gas tends to be acidic, whereas that from metallic sulfide is basic (eq. 1). In the following discussion, unless specified we use H2S to indicate all three species H2S, HS− and S2−.

The bond dissociation energy of H2S is 90 kcal/mol [18], essentially the same as the S-H bond in thiols (92.0 ± 1.0 kcal/mol [47]). The element sulfur can exist in molecules with a broad range of formal oxidation states including −2 as in H2S, 0 as in elemental sulfur (S8), +2 as in sulfur monoxide (SO), +4 as in sulfite (SO32−) and +6 as in sulfate (SO42−). With the lowest oxidation state of −2, the sulfur in H2S can only be oxidized. Therefore, H2S is a reductant. The standard reduction potential under the biochemistry convention (pH = 7 and Eo′(H+/H2) = − 0.421 V) Eo′(S0/H2S) is −0.23 V [48] (Eo′(S0/HS−) = −0.270 V in [49]), which is comparable to the reduction potential under the biochemistry convention of glutathione disulfide / glutathione E′(GSSG/GSH) at 40 °C, −0.24 V [50], and Eo′(cystine/cysteine), −0.340 V [48].2 H2S reduces aromatic azide [52–55] and nitro groups [54] to amine, which is the basis of new fluorescent methods for H2S detection [52–55].

Like thiolate (RS−), HS− is also a nucleophile [56,57] (see 5.1). Its nucleophilic reactions with 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) [58], N-ethylmaleimide [58], parachloromercuribenzoate [58], 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide [59] and monobromobimane [45,60,61] have been utilized for H2S detection. Also based on its nucleophilic property, classes of fluorescent probes for H2S have been recently developed [62–65]. H2S detoxifies the electrophile methylmercury (MeHg+) very likely through a direct reaction which produces a less toxic compound (MeHg)2S [66]. Two intriguing reports have appeared involving nucleophilic attack of postulated signaling molecules by H2S. First, through a nucleophilic displacement reaction, H2S modifies a variety of electrophiles (represented by 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-nitro-cGMP)) involved in redox signaling, then consequently regulates these signaling pathways [67]. Second, Filipovic et al. reported a transnitrosation from nitrosothiol (RSNO) to H2S forming the smallest nitrosothiol, thionitrous acid (HSNO/−SNO) [68]. HSNO/−SNO then potentially transfers nitroso group or donates •NO or nitroxyl (HNO/NO−) to initiate consequent signaling [68].

As will be seen below, the reductive and nucleophilic properties of H2S are likely the most predominant aspects of H2S biochemistry, both of which can contribute to its physiological actions. In the following, we categorize and discuss its reactions based on the postulated biological targets of H2S, oxidants, metals and thiol derivatives.

3. Terminology

One molecular mechanism that has been proposed for H2S as a gasotransmitter is the posttranslational modification of protein cysteine residues forming persulfide (RSSH) [12,69,70]. This process has been called “sulfhydration”, although, as has been pointed out, this terminology does not follow the rule of chemical nomenclature [71]. Persulfide contains so called “sulfane sulfur”. In the path of exploring the mechanisms of the biological functions of H2S, the involvement of “sulfane sulfur” has attracted more and more attention [51]. Here we briefly introduce these terms since they will appear frequently in this review.

Carrying six valence electrons, zero valence sulfur never exists by itself, it can attach to other sulfur(s) forming compounds historically called “sulfanes”. This sulfur-bonded sulfur called “sulfane sulfur” is labile, can be transferred between sulfur-containing structures [20,60,72–74]. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), sulfanes include polysulfides, hydropolysulfides and polysulfanes [1]. Polysulfides are compounds RSnR, where Sn is a chain of sulfur atoms (n ≥ 2) and R ≠ H [1]. When one R = H, they are called hydropolysulfides (RSnH), whereas both R = H called polysulfanes (HSnH) [1]. However, the use of the term “sulfane” is discouraged to avoid confusion, since “sulfane” is actually the newer systematic name for H2S [1]. Here we adapt IUPAC names, for example, hydrodisulfides instead of persulfides or perthiols. For “sulfane sulfur”, our focus here is its property of being transferred between sulfur-containing structures as zero valence sulfur (see 6.3 for the mechanism), therefore, we adopt S0 that has previously been used by Toohey [51] to represent it.

There are a variety of S0-containing compounds [75]. For example, S8 (forming a ring structure), thiosulfate (S2O32−), polysulfanes, hydropolysulfides and certain polysulfides (RSnR when n > 2) [75]. The sulfur in disulfides (RSSR) can also be activated by a double-bonded carbon adjacent to the sulfur-bonded carbon [75]. A typical example is the classic garlic compound diallyldisulfide (DADS) (see 6.3 and eq. 15). S0-containing compounds are widely distributed in nature. Polysulfides are present in a variety of natural products, in particular, they constitute major active components of garlic [76,77]. The sulfur chain also exists in proteins. Rhodanese hydrodisulfide has been crystalized and its crystal structure has been studied at different resolutions [78–82]. Hexasulfide has been found in a rhodanese-like enzyme in bacteria [83]. Recently, a hepta-sulfur bridge was characterized in recombinant human CuZn-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD) [84]. S0 tends to be formed specifically at the “rhodanese homology domain” [85–88] in proteins [51,75]. It is involved in the regulation of the activity of numerous enzymes [89–105]. Combining its special labile property, it is believed to play important roles in biological systems [75,106–109]. It has recently been reported that polysulfide may be a H2S-derived signaling molecule [110].

4. H2S Reaction with oxidants

It has been shown that H2S can be cytoprotective against oxidative stress [111–118]. H2S inhibits the cytotoxicity induced by either peroxynitrite (ONOOH/ONOO−) [119] or hypochlorite (HOCl/−OCl) [120] in SH-SY5Y cells, and the protective effect is comparable to that of GSH. H2S can be converted to sulfite by activated neutrophils. The conversion depends on NADPH oxidase activity and is inhibited by ascorbic acid, indicating the involvement of oxidants [121]. Direct scavenging of oxidants as an antioxidant has been suggested as a mechanism for H2S protection. As a reductant, H2S reacts with oxidants. Although, its nucleophilic properties largely contribute to its reactivity as mentioned above. H2S reactions with oxygen (O2) [41,122–127], hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [128–130] and HOCl/−OCl [128,129] have been extensively studied in environmental solutions. Here we focus more on those studies performed in laboratory solutions, especially those under biological relevant conditions.

4.1 With O2

H2S reaction with O2 (autoxidation) generates polysulfanes, sulfite, thiolsulfate and sulfate as the intermediates and products, although the mechanisms remain undefined due to their complexity [35,131,132]. The thermodynamics and the kinetics of the reaction have been briefly reviewed [133]. Chen et al. concluded that the reaction is too slow overall to be biologically relevant [35]. However, metals [123,126,127,134–139] (also see 5.2.2) and other biological substances such as phenols and aldehydes [134] can accelerate the reaction. Indeed, it has been known since 1958 that certain metalloprotein complexes (including ferritin) can catalyze H2S oxidation [140]. Staško et al. studied the reaction of H2S with two relatively stable radicals 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•) and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation (ABTS•+) (in the absence of a metal chelator), and found that O2 played a dominant role in these reactions [141]. They further investigated H2S autoxidation using spin trapping and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and suggested that the one-electron transfer forming sulfhydryl radicals (HS•/S•−) was one of the primary steps during the reaction [141]. Recently, Hughes et al. showed that the metal chelator diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) prevented the disappearance of H2S under aerobic conditions reemphasizing the catalytic effect of transition metals on H2S autoxidation [29]. Microbes enhance the reaction by three or more orders of magnitude [133] via enzyme systems such as sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (SQR) [142,143]. In mammalian cells, H2S autoxidation is catalyzed by mitochondrial enzymes (including SQR) generating the same intermediates and products as that in the test tube: S0 as in enzyme hydrodisulfide (also see 6.1); sulfite; thiolsulfate (also see 6.3) and sulfate [19,144,145]. This rapid enzymatic process has been suggested to be the mechanism of H2S-regulated oxygen sensing [146–149].

Practically, H2S autoxidation should be taken into consideration during the preparation of the H2S stock solution. Deoxygenation and addition of a metal chelator are suggested to avoid contamination from H2S autoxidation, particularly the bioactive product S0. Toohey believes that S0 actually presents inevitably in an H2S solution, and even the crystal Na2S·9H2O exposed to air is coated with S0 [51]. On the other hand, anhydrous Na2S from Alfa Aesar (Cat. No. 65122) is found to remain pure for several months in a vacuum desiccator [29,45]. Methylene blue also catalyzes H2S autoxidation and the mechanism involves H2O2 as an intermediate (see 4.3) [150,151]. This might at least in part explain the unreliability of the methylene blue method for the measurement of H2S concentration [29,45,152].

4.2 With superoxide (O2•−)

The apparent second order rate constant for the reaction of H2S and O2•− has been determined as different values (Table 1) [153,154]. The difference was explained to be the result of different methods (cytochrome c [154] vs. epinephrine [153]) used to measure the O2•− concentration [154]. The mechanism was not examined in either of these studies.

Table 1.

Apparent second order rate constants of H2S reactions with different oxidants.

| Oxidants | k (M−1 s−1) | Conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| O2•− | 1.5 × 106 | pH 7.8 | [153] |

| (6.5 ± 0.9) × 104 | pH 7.8 and 25 °C | [154] | |

| H2O2 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | pH 7.4 and 37 °C | [155] |

| 1.22 | pH 7.4 and 25 °C a | [156] | |

| ~ 1 | pH 7.8 | [154] | |

| HOCl/−OCl | 2 × 109 | pH 7.4, 25 °C and ionic strength 1.0 M | [157] |

| (8 ± 3) × 107 | pH 7.4 and 37 °C | [155] | |

| ONOOH/ONOO− | (4.8 ± 1.4) × 103 | pH 7.4 and 37 °C | [155] |

| (8 ± 2) × 103 | pH 7.4 and 37 °C | [158] | |

| (3.3 ± 0.4) × 103 | pH 7.4 and 23 °C | [158] | |

| •OH | 1.5 × 1010 | pH 6 | [159] |

| 9.0 × 109 | pH 10.5 | [159] | |

| •NO2 | (3.0 ± 0.3) × 106 | pH 6 and 25 °C | [155] |

| (1.2 ± 0.1) × 107 | pH 7.5 and 25 °C | [155] | |

| CO3•− | (2.0 ± 0.3) × 108 | pH 7.0 and 20 ± 2 °C | [160] |

Calculated based on pKa1 7.0 and Hoffmann’s rate law as discussed in the text.

4.3 With H2O2

The reaction of H2S with H2O2 was utilized more than a century ago to quantitate chemicals including H2S and metallic sulfide [161]. It is an interesting reaction because the pH of the reaction mixture oscillates between acid and base as the reaction proceeds [162,163]. Although the reaction mechanism is still not clear [151,156,161,164–167], the reported rate constants are similar (Table 1) [151,154,156]. Among these studies, Hoffmann’s work [156] deserves to be mentioned because the reaction solution was buffered, metal chelator was added (to avoid the catalytic effect of ferric iron), and the mechanism was examined [167]. This study proposed the rate law of the reaction –

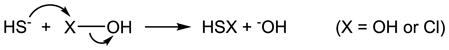

where k1 = 0.008 M−1 s−1, k2 = 0.483 M−1 s−1 and Ka1 is the first dissociation constant of H2S [156]. Polysulfanes were also found as intermediates, which can be formed following the nucleophilic attack of HS− on H2O2 (eqs. 2 and 3 when X = OH) [156]. Demonstration of the direct reaction of H2S with either H2O2 or O2•− has been attempted in a buffered solution [168] and in myocardial mitochondria [169]. There are some caveats in their studies. First, as a general problem for all of these chemiluminescent probes, luminol is not a specific indicator for H2O2, and lucigenin is not a specific indicator for O2•− [170]. Another misunderstanding that is also very common is to use the xanthine oxidase / (hypo)xanthine system as a positive control for O2•− generation, which actually produces much more H2O2 than O2•− under most conditions [171,172]. In addition, the control experiments for the effects of H2S alone on these assays are very important due to the complexity of the reactions, and are not mentioned in the reports [168,169]. Similar problems apply to another report claiming that H2S directly scavenges H2O2 as measured by ferrous oxidation – xylenol orange (FOX) assay [173].

|

(2) |

| (3) |

4.4 With HOCl/−OCl

It has been shown that H2S scavenges HOCl/−OCl and its common derivative taurine chloramine as measured by 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) oxidation [173]. The same problem as mentioned in 4.3 is that the control of the H2S effect on the assay is not reported, although the authors did mention that higher concentrations of H2S can reduce the product of TMB oxidation [173]. Nagy and Winterbourn found that the overall reaction of H2S with HOCl/−OCl is extremely fast with an apparent second order rate constant of 2 × 109 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.4 (Table 1). HOCl is more reactive than −OCl, which is consistent with the possible mechanism that nucleophilic displacement by H2S is the rate limiting step (eq. 2 when X = Cl) [157]. In spite of the fact that the direct scavenging of HOCl/−OCl by H2S is almost diffusion limited, it is still less relevant to the protective effect of H2S in vivo because of its low concentration compared to other antioxidants [157]. However, S0 is produced during the reaction (eq. 3 when X = Cl), which has the potential to mediate signaling pathway(s) for the protection [157].

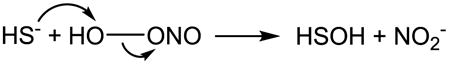

4.5 With ONOOH/ONOO−

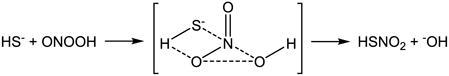

Carballal et al. performed a broad study on H2S reactions with oxidants including H2O2, HOCl/−OCl, and particularly ONOOH/ONOO− and its downstream intermediates (•OH, •NO2 and CO3•−) [155]. The rate constants included in their study are summarized in Table 1. Similar to the proposed mechanisms for the reaction of H2S with H2O2 and HOCl/−OCl, they suggest that the reaction of H2S with ONOOH/ONOO− involves an initial nucleophilic attack on ONOOH/ONOO− by H2S (eq. 4) and then downstream steps involving S0 formation (eq. 3 when X = OH). Although H2S has comparable reactivity as the classic antioxidants cysteine and GSH, the direct scavenging of oxidants is unlikely to contribute to its antioxidant activity due to its relatively lower concentration in vivo [155]. This is in agreement with Nagy and Winterbourn’s conclusion as discussed in 4.4 [157]. Theoretical studies suggest that the concerted two-electron oxidation of H2S by peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH) is energetically feasible based on the calculated activation energy of 17.8 kcal/mol [174]. Filipovic et al. reported a slightly higher rate constant for H2S reaction with ONOOH/ONOO− ((3.3 ± 0.4) × 103 M−1 s−1 at 23 °C and (8 ± 2) × 103 M−1 s−1 at 37 °C, Table 1), but declared a different mechanism from the multi-step mechanism that is well accepted for thiols and proposed by Carballal et al. for H2S [158]. Interestingly, they proposed an associative mechanism that is consistent with the theoretical prediction (eq. 5) and identified sulfinyl nitrite (HS(O)NO) as the major product, which can consequently generate •NO (eq.6) [158].

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

| (6) |

4.6 With •NO

There has been more and more attention paid to the “cross talk” between H2S and •NO [21–27,175]. The direct reaction between the two has been investigated primarily by two groups, Moore’s and Bian’s.

Moore’s group suggested nitrosothiol formation from the reaction [176–179]. However, as has been pointed out by King [180], the direct reaction between H2S and •NO requires oxidation, same as the putative reaction of thiol with •NO forming S-nitrosothiol [181]. Experimentally, Moore et al. provide evidence for nitrosothiol formation from the specific reaction of mercury chloride (HgCl2) with nitrosothiol and the consequent measurement of nitrite and •NO formation [178], however, detailed interpretations are not provided. Here we present a few major concerns. First, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was used as an •NO donor, which actually can directly react with H2S [182] through a mechanism that is still in debate [183,184]. This problem has also been brought to light by King [180]. In addition, 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) was also used as an •NO donor, which actually produces •NO and O2•− simultaneously [185] and consequently ONOOH/ONOO− [186] and other species [187]. Second, the nitrite formation from donors SIN-1, 3-bromo-3,4,4-trimethyl-3,4-dihydrodiazete 1,2-dioxide (DD1) and (Z)-1-[2-(2-aminoethyl)-N-(2-ammonioethyl)amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (DETA NONOate) were not inhibited by H2S. In the case of SIN-1 and DD1, the addition of HgCl2 reversed the nitrite formation to a level even higher than the control (donor alone). In spite of the fact that HgCl2 reacts with nitrosothiol producing nitrosonium (NO+) instead of •NO [188,189], a tremendous increase of •NO generation upon HgCl2 addition was detected by the •NO electrode, which is not consistent with their nitrite measurement. Third, N-[4-[1-(3-aminopropyl)-2-hydroxy-2-nitrosohydrazino]butyl]-1,3-propanediamine (SPER NONOate) by itself will not generate an EPR signal (Fig. 3A in their publication), a spin trap must have been used, but it was not stated in the report. Lastly, the direct reaction between HgCl2 (an electrophile) and H2S (a nucleophile) should be considered. As mentioned above, H2S reacts with parachloromercuribenzoate [58], and potentially with MeHg+ [66].

Bian’s group suggested the nitroxyl (HNO/NO−) formation from the reaction of H2S and •NO, which is simply based on the similar result obtained using Angeli’s salt, an HNO donor [190]. However, in their later report, HNO/NO− was not mentioned specifically and “a new biological mediator” was suggested instead [191].

4.7 With lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH)

Jeney et al. found that H2S delayed product accumulation from lipid peroxidation induced by hemin [192]. By showing that one type of the peroxidation products, LOOH, decreases in the oxidized lipids after H2S treatment, which correlates with the decrease in cytotoxicity of these oxidized lipids, it was hypothesized that the direct reaction of H2S and LOOH could be a potential mechanism for H2S cytoprotection. Muellner et al. also found that H2S could diminish LOOH formed from Cu2+-initiated lipid peroxidation [193]. Relative to their data obtained by FOX assay (also used by Jeney et al.), their high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) measurement of both (9S)-hydroperoxy-(10E,12Z)-octadecadienoic acid (a LOOH) and its reduced product (9S)-hydroxy-(10E,12Z)-octadecadienoic acid provided more convincing evidence for the direct reaction between H2S and LOOH. Studies on the kinetics and the mechanisms of H2S reactions with reactive lipids are needed.

4.8 With other oxidants

It has also been reported that H2S can scavenge the triplet state of riboflavin and radicals of tyrosine and tryptophan generated by photolysis, and can therefore protect the lysozyme from damage [194]. H2S also has the potential to react with nitrated fatty acid, an electrophile, which is another •NO-derived signaling molecule [195]. However, studies on the chemical reactions and mechanisms are needed.

5. H2S Reaction with metals

5.1 With inorganic iron: chemical concepts

The chemical interactions of sulfur species and metals fall into two basic categories, oxidation/reduction and ligation. In oxidation/reduction, complete electron transfer occurs between the sulfur species and the metal, while ligation (binding of the sulfur species to the metal) involves the formation of what is referred to in inorganic chemistry as a coordinate complex. Both of these interactions are predicted by the chemical properties of sulfur-containing molecules as nucleophiles.

The common definition of acids and bases is that an acid is a proton donor and a base is a proton acceptor. In 1923 Gilbert N. Lewis (University of California Berkeley) proposed a more general (and thus more useful) definition, that an acid is an electron pair acceptor and a base is an electron pair donor [196]. In 1929 Christopher K. Ingold (University of Leeds) introduced the terms nucleophile and electrophile to denote species that act by either donating (nucleophile) or accepting (electrophile) their electrons [197]. A further nuance is the current notion that a nucleophile is a species that is “electron rich” and thus exhibits affinity for species that are “electron poor” (electrophile).

Transition metal ions are positively charged (many times with multiple charges) and thus are electrophiles. In pure aqueous solution metal ions such as iron (Fe2+/Fe3+) do not exist “free” but attract and organize water molecules around them in specific geometries. Water is a relatively weak nucleophile so it is displaced by others that are stronger. Sulfur-containing molecules, including H2S, are strong nucleophiles and will bind to iron in aqueous solution. Thus, when H2S is added it will displace the water bound to the iron. If H2S is the only nucleophile, the resulting binding to the iron results in an insoluble precipitate. Undoubtedly the insolubility of metal sulfides is their most industrially important general chemical property, which has been exploited for many uses, including methods of analysis of metals and metal mixtures [198]. The structures that are formed when nucleophilic ligands (the term for the nucleophiles that bind in specific geometric positions around the central metal ion) bind noncovalently to a metal ion are called complexes.

5.2 With biological iron

5.2.1 With heme iron

Cytochrome c oxidase

By far the most studied hemoprotein for H2S interaction is mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) [199]. The inhibition of this enzyme is generally believed to be the basis of the toxicity of H2S exposure, which is second only to cyanide for work-related gaseous fatalities [200]. However, rather than toxicity it has been shown that administration of H2S to mice results in a suspended animation-like state which appears attributable to the inhibition of respiration via cytochrome oxidase [201], as described in the accompanying review in this issue.

Interaction between CcO and H2S was first described by Keilin in 1929 [202] and has been studied by several investigators (although virtually all studies have been done under nonphysiological conditions of high H2S concentrations and sometimes long incubation times). H2S interacts with CcO through the O2-binding copper (CuB) / heme (a3) iron binuclear site in the oxidized state (Cu2+/Fe3+) [199]. H2S both binds to and reduces CcO [203], which may be key to its salutatory, as opposed to toxic, activities even though comparable respiratory inhibition with other “pure” inhibitors causes death [199,201,204].

Small molecule sensor hemoproteins

Studies over the past couple of decades have revealed that nature has evolved an array of hemoprotein sensors that are specific for small diatomic nonelectrolytes (O2, •NO, CO) [205–208]. The phenomena that are responsible for the remarkable specificity of each of these sensors for their cognate ligands are multiple and illustrate the critical importance of the protein structure, both surrounding the heme group and also pathways in the protein that provide access of the ligand to the heme pocket. These phenomena include heme pocket polarity, distal ligand(s), cavities around the heme, and strength of proximal histidine-iron bonding. The “fine tuning” of hemoproteins to induce ligand-specific interactions is elegantly illustrated with H2S as ligand by studies with a mollusk/bacterial symbiosis [209–212]. In this relationship, cytoplasmic hemoglobins (reaching concentrations of 1.5 mM) in the gills of the clam host deliver O2 and H2S to the colonizing chemoautotrophic bacteria that utilize the H2S metabolically to provide nutrients for the host.

Hemoglobin/Myoglobin and other hemoproteins

It has been known for many years that H2S forms a tight complex to methemoglobin [213], and induced methemoglobinemia exerts protection against H2S toxicity in vivo [214]. By far the best known interaction of H2S with hemoglobin or myoglobin is in the presence of O2 or H2O2 to generate the species sulfhemoglobin or sulfmyoglobin, which is a covalent heme modification generating an intensely green color that is diagnostic of H2S poisoning [215]. The mechanism of this reaction has been proposed to involve the formation of a ternary complex of H2S, ferryl (or peroxo) heme, and a distal histidine [216]. The relevance of this toxicological phenomenon (or the comparable derivatives of other hemoproteins such as catalase [217] and lactoperoxidase [218]) to the biological signaling aspects of H2S is unclear.

5.2.2 With nonheme iron

Iron-sulfur clusters

In 1960, Beinert and Sands reported the appearance of a unique low-temperature EPR signal upon reduction of preparations of mitochondrial succinic and NADH dehydrogenase [219]. It is now known that this and related signals are due to the ubiquitous presence of iron-sulfur centers, protein-bound complexes of iron and sulfur [220]. The most abundant structures (distributed throughout all three biological kingdoms) possess the iron / sulfur stoichiometry Fe2S2 or Fe4S4 with each iron of approximately tetrahedral coordination with two sulfur and two protein-contributed (usually cysteine thiol) ligands. For much of the time since their discovery, it has been generally accepted that, the function of these clusters is a carrier of electrons and in fact these centers are the most abundant electron carrier in the mitochondrion, outnumbering all other electron carriers (hemes, flavins). It is now known that these unique protein components serve a remarkable variety of biological functions in addition to electron transfer, principally as sensors for oxidative stress and also for cellular iron homeostasis [221].

As noted in 5.1, iron forms mostly insoluble precipitates with H2S forming a vast array of both regular and irregular structures. In the cell, however, an extensive machinery has evolved for the formation and incorporation of specific iron-sulfur centers into proteins. It has been shown that the sulfur in iron-sulfur centers originates from cysteine thiol and is transferred as S0 bound to the sulfurtransferase component in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems [222].

Chelatable or labile iron pool

The formation of insoluble precipitate with added H2S has been used as early as 1850 to visualize tissue iron [223]. This suggests that in cells H2S could function biologically to mask the chelatable or labile iron pool and prevent formation of highly reactive oxygen species and thus contribute to its salutatory function in a variety of pathologies involving disturbances in O2, a possibility for which there is indeed evidence [224]. However, as mentioned in 4.1, metal catalyzes H2S autoxidation that causes reactive oxygen species formation and consequent oxidative damage to cellular components (including DNA) [139].

5.3 With other cellular transition metals

The only reported reaction of H2S with a copper-containing protein (with the exception of CcO, see 5.2.1) is CuZn-SOD, where the reaction involves copper-catalyzed reduction of O2•− to H2O2 and oxidation of H2S to S0 [154]. This process may be functionally important in terms of modulation of cellular signaling from reactive oxygen species.

6. H2S Reaction with thiol derivatives (or thiol reaction with oxidized H2S)

Although still being questioned [225–227], S-nitrosation of protein thiols has been proposed to be a cGMP-independent mechanism for •NO signaling [228,229]. Analogously, it has been suggested that H2S can mediate signaling through so called “sulfhydration” of protein cysteine residues forming hydrodisulfides [12,69,70,230–233]. The same mechanism has been postulated for H2S neurotoxicity [234]. However, it is important to realize that H2S does not directly react with thiol. As discussed above, H2S is a reductant, it will not react with another reductant such as thiol. Also, both HS− and RS− are nucleophiles, therefore will not react with each other.

Similar to •NO reaction with thiol forming S-nitrosothiol (eq. 7) [181], H2S reaction with thiol forming hydrodisulfide needs oxidation (eq. 8). N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in combination with metronidazole is effective in ethylmalonic encephalopathy [235]. The proposed mechanism for the effectiveness of NAC is the increase of GSH production that in turn detoxifies H2S to GSH hydrodisulfide (GSSH), which is catalyzed by SQR [235]. As pointed out by the authors, the electron of the apparent reaction of GSH and H2S forming GSSH (an oxidation) is transferred to coenzyme Q and therefore coupled to the mitochondrial respiratory chain [235]. Some S0-containing compounds including hydrodisulfides have been chemically synthesized [236–238], we here focus on the direct reactions between H2S and thiol derivatives, or thiol and oxidized H2S, that can possibly form hydrodisulfide under biological conditions. For each type of reaction, we summarize the initial studies on the test tube chemistry, then those biologically relevant studies, and eventually list their speculated occurrences in almost every aspect of H2S biology and methodology.

| (7) |

| (8) |

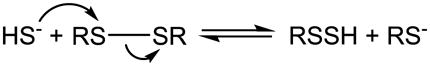

6.1 H2S reduces oxidized thiol, disulfide

The mechanism is most likely to be a nucleophilic displacement as shown in eq. 9. which is analogous to the disulfide-thiol exchange reaction.

|

(9) |

Under alkaline conditions, cystine reacts with Na2S forming hydrodisulfide that is characterized by its maximal absorption at 335 nm [239]. The reaction is very reversible, the rate constants for the reaction and the reverse reaction were determined as 3.7 ± 0.4 M−1 min−1 and 5.5 ± 0.6 M−1 min−1 respectively at 25 °C, pH 10.0 and ionic strength 0.17 M [240]. A mixture of lipoate (the oxidized disulfide form of dihydrolipoate) and Na2S in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) also produces hydrodisulfide as measured by an absorption peak at 335 – 340 nm [241]. This reaction was also suggested by Schneider et al. when they studied the hydrodisulfide formation from disulfides alone (see 6.2) [242]. Cavallini et al. studied the interaction of proteins with H2S in 0.01 M NaOH [243]. Disulfide-containing proteins including insulin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), ribonuclease, chymotrypsinogen A and ovalbumin all react with H2S to form hydrodisulfide. The apparent second order rate constants at 25°C were reported as 2.2 M−1min−1 for cystamine, 0.35 M−1min−1 for cystine (lower than that from [240]), 2.3 M−1min−1 for denatured BSA and 4 M−1min−1 for denatured insulin respectively. The reactions also occur at lower pH between 8 and 9. However, proteins that do not contain cysteine or intramolecular disulfide such as gelatin and casein do not react. The accessibility of the protein disulfide bonds to H2S was found to be important for hydrodisulfide formation.

More recently, cysteine was detected from the reduction of cystine by NaHS in culture medium, the hydrodisulfide formation was not studied [115]. In spite of the importance of GSH/GSSG in maintaining the redox balance in biological systems, reaction 9 has not been tested for GSSG until recently. Francoleon et al. studied the reaction of GSSG and H2S under physiologically relevant conditions, and observed GSSH formation by different methods [95]. Reaction 9 may also occur physiologically in disulfide-containing proteins [19] and may be catalyzed by enzymes. The molecular mechanism of the stimulation of ATP-sensitive potassium ion (KATP) channels by H2S has been suggested to involve the interaction of H2S with the disulfide possibly formed between the two vicinal cysteines in the extracellular loop of the channels [244]. Within the three sequential enzymes that catalyze H2S autoxidation in mitochondria, SQR catalyzes the first step, H2S oxidation to S0. This enzymatic reaction is initiated by the reaction of H2S with SQR disulfide forming SQR hydrodisulfide [144].

As mentioned above, reaction 9 is reversible. The reverse reaction is the key step in the proposed mechanism for the endogenous generation of H2S from garlic [245]. It may also be involved in the endogenous generation of H2S via 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST) and cysteine transaminase [246]. Thioredoxin or dihydrolipoate is required for 3MST to produce H2S, therefore, a mechanism of dithiol reaction with 3MST hydrodisulfide (through transsulfuration from 3-mercaptopyruvate (3MP) to 3MST cysteine thiol as described in 6.3) producing an inner disulfide and H2S has been proposed [246]. The reverse reaction has also been applied to measure S0 using dithiothreitol (DTT) as the reductant [73,234,247–252].

6.2 Disulfide alone in the absence of H2S

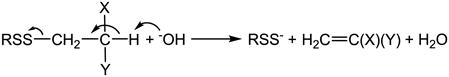

Disulfide itself can be converted to hydrodisulfide in the absence of H2S. Incubation of insulin in 0.5 M NaOH showed a maximal spectral change at 370 nm indicating hydrodisulfide formation [242]. Among postulated mechanisms [253–256], Tarbell and Harnish first suggested the mechanism that OH− abstracts a proton from the β carbon of the sulfur atom followed by α,β-elimination and hydrodisulfide formation (eq. 10) [257]. Schneider et al. studied the structural effect of the disulfides (by using cystine and its derivatives, GSSG and insulin therefore changing the substitutes X and Y in eq. 10) on hydrodisulfide formation, and their results supported the elimination mechanism [242].

|

(10) |

Reaction 10 does occur under physiological pH with the assistance of pyridoxal or pyridoxal phosphate, and has been applied to generate hydrodisulfide under physiologically relevant conditions [105,258]. A similar elimination mechanism (through Schiff base formation with pyridoxal or pyridoxal phosphate) has been suggested for cystine (CysSSCys) desulfuration by cystathionase at physiological pH (eq. 11) [258–261].

| (11) |

The product cysteine hydrodisulfide (CysSSH) then transfers S0 to other thiols (also see 6.3). This is thought to be the mechanism of the activity alteration of some enzymes by cystathionase/cystine [96,262–266]. It is worth mentioning that in order for cysteine instead of cystine to inhibit tyrosine aminotransferase in the presence of cystathionase, a cysteine oxidase is required [267]. This once again emphasizes the fact that for a thiol to form hydrodisulfide, an oxidation is needed. Certain garlic derived disulfides can also be the substrate of cystathionase producing hydrodisulfides [268], and the same mechanism is considered to be responsible for the therapeutic effects of garlic [269]. Further, more enzymes are found possessing the same activity as cystathionase [270,271]. Toohey suggests that the two enzymes involved in H2S biosynthesis, cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) and CSE, should have the same activity and therefore argues that it is S0 not H2S that is formed from the enzymatic reaction [51].

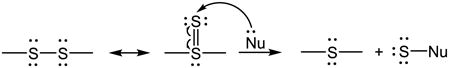

6.3 Thiol reacts with the oxidized H2S, S0

Since S0 does not exist by itself, the reaction is actually between thiol and S0-containing compounds. A very important as well as interesting reaction of S0 is its transfer between sulfur structures through the formation of thiosulfoxide tautomer (eq. 12) [51,272]. With an empty orbital, the sulfoxide sulfur in the tautomer can interact with a nucleophile (Nu) and consequently S0 is transferred (eq. 12). Therefore, the reaction is called transsulfuration. When the nucleophile is cyanide (−CN), thiocyanate (−SCN) is produced, which can simultaneously bind ferric iron forming a complex (Fe(SCN)63−) with characteristic maximal absorbance at 460 nm [74]. This is the chemical basis of the method called cyanolysis that is used for S0 detection [74]. When the nucleophile is a thiol, hydrodisulfide can be formed via the S0 transfer. The formed hydrodisulfide can further react with S0 forming hydropolysulfides (eq. 13), which can react with each other generating polysulfides and H2S (eq. 14, including the reverse reaction of eq. 9). As described for the reverse reaction of eq. 9 in 6.1, reaction 14 indicates an additional mechanism for H2S generation.

|

(12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

S0 was detected from the filtrate of a pH 9.1 mixture of S8 and thiol (mercaptoethanol, mercaptopyruvate and cysteine) or H2S, indicating the transsulfuration from S8 to thiol or H2S [273]. Cavallini et al. suggested that the reaction of cysteine and S8 in alkaline solution could produce hydrodisulfide [259]. The downstream product cysteine trisulfide (CysSSSCys) has been synthesized from the reaction, but not hydrodisulfide probably due to its instability [274]. In the study of H2S reaction with cystine in basic solution (discussed in 6.1), the transsulfuration between cysteine and disulfane (HS2−) was suggested [239]. The rate constants for the reaction and the reverse reaction were determined as 122 ± 20 M−1 min−1 and 6.1 ± 0.5 M−1 min−1 respectively at 25 °C, pH 10.0 and ionic strength 0.17 M [240]. In the case of GSH, a nucleophilic attack of GSH on the S8 ring has also been suggested [275–277]. The resulting GSSH then reacts further to form GSH polysulfide (GSnG, n > 2) and to produce H2S [275–277]. From the anaerobic reaction of GSH and S8 at pH 7.5, Rohwerder et al. detected the formation of GSSG and its higher homologous products up to GS5G [275]. Again, the hydrodisulfide might be too reactive to be detected [275].

Francoleon et al. studied S0 transfer from GSSH to papain cysteine thiol and found consequent inhibition of protein activity [95]. Actually transsulfuration from low molecular weight S0-containing compounds to protein thiols is believed to contribute to the activity changes in a variety of enzymes [89,92,96,99–101,105]. Transsulfuration can be accelerated by sulfurtransferases. Rhodanese assists S0 transfer from thiosulfate to other enzymes and consequently modulates their activities [89,90,103,104]. In addition, it is proposed to be the enzyme that catalyzes the final step of H2S autoxidation in mitochondria, which is the S0 transfer from SQR hydrodisulfide to sulfite forming thiosulfate [19,144]. 3MST catalyzes S0 transfer from 3MP to an acceptor [278,279] via 3MST hydrodisulfide formation [273,280] (although 3MP does not have the typical structure of S0-containing compounds, its sulfur is labile [281] due to the adjacent carbonyl group C=O). Adrenal ferredoxin may be an acceptor to serve its function on iron-sulfur chromophore formation [102]. Thioredoxin can also be an acceptor, and the resulting thioredoxin hydrodisulfide could undergo further S0 transfer to perform its biological roles [282]. As described in 6.1, thioredoxin hydrodisulfide may also react with its adjacent thiol forming inner disulfide and releasing H2S (reverse reaction of eq. 9) [19,246].

Another mechanism for hydrodisulfide formation from thiol reaction with S0-containing compound has been proposed as the initial reactions of H2S production from garlic compounds in the presence of GSH. It is simply a nucleophilic displacement initiated by the nucleophilic attack of GSH on the α position of the S-S unit of a garlic compound (eq. 15) [76,77,245,283]. The α position can be the α carbon of an allyl group (as in DADS), and can also be a sulfur (as in trisulfides) (eq. 15). The hydrodisulfides that are formed then further react with GSH liberating H2S (reverse reaction of eq. 9).

| (15) |

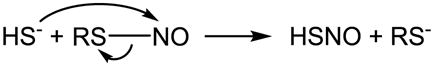

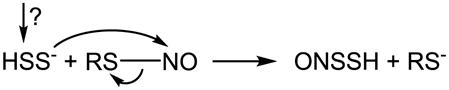

6.4 H2S reacts with S-nitrosothiol

It has been reported that H2S very rapidly reacts with S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO), S-nitrosopenicillamine or S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) generating a relatively stable UV spectrum with a peak absorption at 410 nm [284]. Compared with previous reports [285,286], this spectrum was assigned to a hydrodisulfide ONSSH/ONSS− [284]. One speculated mechanism involves an initial nucleophilic attack of H2S on RSNO forming HSNO/−SNO (eq. 16) [287–291]. It was also suggested that HSNO/−SNO consequently reacted with another H2S forming ONSSH/ONSS− [284], although an oxidant is needed for the reaction (eq. 17). Alternatively, HS2− originating from an unknown mechanism (RSSR was suggested to be a candidate) could react with RSNO via nucleophilic displacement (eq. 18) [284]. Others found that the reaction of H2S with RSNO released •NO [292–294]. By measuring •NO formation, this reaction was applied to quantitate the amount of RSNO [293]. As has been mentioned, the detailed study by Filipovic et al. supported HSNO/−SNO formation during the reaction, which could consequently donate •NO, nitroso group or HNO/NO− [68]. Although their data do not support the direct formation of hydrodisulfide and HNO/NO− for low molecular weight RSNO, it may hold true for protein RSNO (eq. 19) [68]. A good mechanistic rationale and comparison to the reaction between RSH and RSNO can also be found in King’s review [180].

|

(16) |

| (17) |

|

(18) |

| (19) |

6.5 Other proposed mechanisms

According to eq. 8, hydrodisulfide may be formed from reactions of other oxidized thiols and H2S, or other oxidized H2S and thiols. It has been deduced that hydrodisulfide mediates the reaction of H2S with oxidized thiols, thiosulfate ester (RS-SO2-OH) [295,296] and cystinedisulfoxide [297]. Another ideal candidate for the oxidized thiol, sulfenic acid, has also been suggested to react with H2S forming protein hydrodisulfide [19,20,157]. Other oxidized sulfur species that have been proposed to react with thiol forming hydrodisulfide include the simplest sulfenic acid HSOH [20], and HS(O)NH2 that can be generated from the reaction of H2S with HNO/NO− [68].

7. Conclusions

There has been an explosion of publications claiming the beneficial effects of H2S, and in the enthusiasm, it appears that an extensive chemical literature on H2S has often been neglected. As discussed above, a few factors that need to be considered during H2S manipulation include the purity of its donor, its volatility, its reaction with O2 and the possible pH change in the solution. In spite of these complications, the way H2S stock solutions are prepared is rarely mentioned in research reports. A relatively cautious method and a good description can be found in [245,298,299]. Although not a focus here, it has been pointed out by many researchers that a major problem in H2S research is a lack of reliable methods to precisely and specifically measure H2S ([45,152,300] and the accompanying review in this issue). Physiological concentrations of H2S that are different in orders of magnitude have been reported [44–46]. Without doubt, H2S chemistry is the basis for the development of new detection methods.

Some speculations in the literature regarding the actions of H2S are not based on sound chemical principles. H2S has been described as an antioxidant to explain its ability to protect against oxidative stress. However, the chemistry shows that the direct scavenging of oxidants by H2S is unlikely due to the lower concentration of H2S compared to other antioxidants in vivo. Another mechanism is the protein post-translational modification by H2S generating S0 that is involved in almost every aspect of H2S chemistry, and that has the high potential of transducing signals owing to its unique property of transsulfuration. So is it H2S or S0 that is the signaling molecule implicated in diverse biological processes [51]? In addition, the metabolism of sulfur-containing molecules including cysteine, GSH, H2S, S0-containing molecules and many others are highly related [60,115,301–303], an overall estimation of the sulfur flow upon H2S addition would be informative for determining the actual mechanism. Better and more efficient tools for the detection of these sulfur-containing species are highly needed. Fluorescent probes for the detection of S0 have been recently developed [304], their applications in biological systems need to be examined.

In all, without these concerns being addressed, the title of H2S as a gasotransmitter or signaling molecule should not be awarded. As has been pointed out, critical opinions and “brakes” are urgently needed in H2S research to reveal the authentic biological mechanisms of this interesting molecule [152,305–308].

Highlights.

includes a comprehensive survey of literatures on the basic physical and chemical properties of H2S and H2S chemistry,

focuses on the chemical foundation of H2S biology and methodology,

introduces standard terminology to the H2S field,

calls attention to chemical misconceptions in the studies of H2S.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ming Xian for helpful discussion of the chemistry described in this review. This work is supported by an internal grant from the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham (to QL) and NIH grant CA-131653 (to JRL).

Footnotes

A note of terminology, the definition of a “gas” is a substance possessing perfect molecular mobility and the property of indefinite expansion to fill the available space. This is true of each of these substances in the pure state under standard conditions but obviously does not accurately describe the physical properties of these substances (as well as O2 and CO2) in virtually all of their biological actions which are more appropriately described as dissolved noneletrolytes.

A value of + 0.17 V for the reduction potential of S0/HS− has been used to compare to −0.25 V for the reduction potential of GSH and cysteine [19,51], however, it is very likely that the former is relative to the H+/H2 standard under the convention of physical chemistry (pH = 0 and Eo(H+/H2) = 0 V) whereas the latter is relative to Eo′(H+/H2) of −0.421 V [48].

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) Compendium of Chemical Terminology Gold Book, Version 2.3.2. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide: its production and functions. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:833–835. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.057455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King AL, Lefer DJ. Cytoprotective actions of hydrogen sulfide in ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:840–846. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.059725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson CK, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteman M, Winyard PG. Hydrogen sulfide and inflammation: the good, the bad, the ugly and the promising. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4:13–32. doi: 10.1586/ecp.10.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura H, Shibuya N, Kimura Y. Hydrogen sulfide is a signaling molecule and a cytoprotectant. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:45–57. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Rose P, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide and cell signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:169–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Snyder SH. Signaling by gasotransmitters. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.268re2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, Snyder SH. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandiver M, Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide: a gasotransmitter of clinical relevance. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0873-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner F, Asfar P, Calzia E, Radermacher P, Szabo C. Bench-to-bedside review: Hydrogen sulfide-the third gaseous transmitter: applications for critical care. Crit Care. 2009;13:213. doi: 10.1186/cc7700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu X, Zhu YZ. Therapeutic applications of organosulfur compounds as novel hydrogen sulfide donors and/or mediators. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4:123–133. doi: 10.1586/ecp.10.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martelli A, Testai L, Marino A, Breschi MC, Da SF, Calderone V. Hydrogen sulphide: biopharmacological roles in the cardiovascular system and pharmaceutical perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3325–3336. doi: 10.2174/092986712801215928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashfi K, Olson KR. Biology and therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing chimeras. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:689–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuto JM, Carrington SJ, Tantillo DJ, Harrison JG, Ignarro LJ, Freeman BA, Chen A, Wink DA. Small molecule signaling agents: the integrated chemistry and biochemistry of nitrogen oxides, oxides of carbon, dioxygen, hydrogen sulfide, and their derived species. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:769–793. doi: 10.1021/tx2005234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabil O, Banerjee R. Redox biochemistry of hydrogen sulfide. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21903–21907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.128363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Gojon G. Hydrogen sulfide in biochemistry and medicine. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:119–140. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bir SC, Kolluru GK, McCarthy P, Shen X, Pardue S, Pattillo CB, Kevil CG. Hydrogen sulfide stimulates ischemic vascular remodeling through nitric oxide synthase and nitrite reduction activity regulating hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent angiogenesis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e004093. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coletta C, Papapetropoulos A, Erdelyi K, Olah G, Modis K, Panopoulos P, Asimakopoulou A, Gero D, Sharina I, Martin E, Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9161–9166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202916109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fago A, Jensen FB, Tota B, Feelisch M, Olson KR, Helbo S, Lefevre S, Mancardi D, Palumbo A, Sandvik GK, Skovgaard N. Integrating nitric oxide, nitrite and hydrogen sulfide signaling in the physiological adaptations to hypoxia: A comparative approach. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2012;162:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Predmore BL, Kondo K, Bhushan S, Zlatopolsky MA, King AL, Aragon JP, Grinsfelder DB, Condit ME, Lefer DJ. The polysulfide diallyl trisulfide protects the ischemic myocardium by preservation of endogenous hydrogen sulfide and increasing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2410–H2418. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00044.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomaskova Z, Bertova A, Ondrias K. On the involvement of H2S in nitroso signaling and other mechanisms of H2S action. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:1394–1405. doi: 10.2174/138920111798281009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R. Shared signaling pathways among gasotransmitters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8801–8802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206646109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauchamp RO, Jr, Bus JS, Popp JA, Boreiko CJ, Andjelkovich DA. A critical review of the literature on hydrogen sulfide toxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1984;13:25–97. doi: 10.3109/10408448409029321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes MN, Centelles MN, Moore KP. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide: The chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calhoun DB, Englander SW, Wright WW, Vanderkooi JM. Quenching of room temperature protein phosphorescence by added small molecules. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8466–8474. doi: 10.1021/bi00422a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Moore PK. Putative biological roles of hydrogen sulfide in health and disease: a breath of not so fresh air? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Bruyn WJ, Swartz E, Hu JH, Shorter JA, Davidovits P, Worsnop DR, Zahniser MS, Kolb CE. Henry’s Law solubilities and Setchenow coefficients for biogenic reduced sulfur species obtained from gas-liquid uptake measurements. J Geophys Res. 1995;100:7245–7251. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathai JC, Missner A, Kugler P, Saparov SM, Zeidel ML, Lee JK, Pohl P. No facilitator required for membrane transport of hydrogen sulfide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16633–16638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902952106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen KY. PhD Thesis/Dissertation: Oxidation of aqueous sulfide by O2. Harvard University, Division of Engineering and Applied Physics; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen KY, Morris JC. Kinetics of oxidation of aqueous sulfide by O2. Environ Sci Technol. 1972;6:529–537. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sillen LG, Martell AE. Stability Constants of Metal-Ion Complexes, Special Publ. 17. Chemical Society; London, England: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giggenbach W. Optical spectra of highly alkaline sulfide solutions and the second dissociation constant for hydrogen sulfide. Inorg Chem. 1971;10:1333–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peramunage D, Forouzan F, Licht S. Activity and spectroscopic analysis of concentrated solutions of potassium sulfide. Anal Chem. 1994;66:378–383. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lide DR. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Housecroft CE, Constable EC. Chemistry: An Introduction to Organic, Inorganic, and Physical Chemistry. 2. Prentice Hall; New Jersey: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millero FJ. The thermodynamics and kinetics of the hydrogen sulfide system in natural waters. Mar Chem. 1986;18:121–147. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millero FJ, Hershey JP. Thermodynamics and kinetics of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. In: Saltzman ES, Cooper WJ, editors. Biogenic Sulfur in the Environment. American Chemical Society; Washington, D.C: 1989. pp. 282–313. [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLeon ER, Stoy GF, Olson KR. Passive loss of hydrogen sulfide in biological experiments. Anal Biochem. 2012;421:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furne J, Saeed A, Levitt MD. Whole tissue hydrogen sulfide concentrations are orders of magnitude lower than presently accepted values. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1479–R1485. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90566.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen X, Pattillo CB, Pardue S, Bir SC, Wang R, Kevil CG. Measurement of plasma hydrogen sulfide in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, Skovgaard N, Olson KR. Reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1930–R1937. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benson SW. Thermochemistry and kinetics of sulfur-containing molecules and radicals. Chem Rev. 1978;78:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voet D, Voet JG. In: Introduction to metabolism. Harris D, Fitzgerald P, editors. Biochemistry, John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelly DP. Biochemistry of the chemolithotrophic oxidation of inorganic sulphur. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;298:499–528. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rost J, Rapoport S. Reduction-potential of glutathione. Nature. 1964;201:185. doi: 10.1038/201185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toohey JI. Sulfur signaling: is the agent sulfide or sulfane? Anal Biochem. 2011;413:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen S, Chen ZJ, Ren W, Ai HW. Reaction-based genetically encoded fluorescent hydrogen sulfide sensors. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9589–9592. doi: 10.1021/ja303261d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lippert AR, New EJ, Chang CJ. Reaction-based fluorescent probes for selective imaging of hydrogen sulfide in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10078–10080. doi: 10.1021/ja203661j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montoya LA, Pluth MD. Selective turn-on fluorescent probes for imaging hydrogen sulfide in living cells. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48:4767–4769. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30730h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng H, Cheng Y, Dai C, King AL, Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Wang B. A fluorescent probe for fast and quantitative detection of hydrogen sulfide in blood. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:9672–9675. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dittmer DC. Hydrogen Sulfide, Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. Wiley; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearson RG, Sobel H, Songstad J. Nucleophilic reactivity constants toward methyl iodide and trans-dichlorodi(pyridine)platinum(II) J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nashef AS, Osuga DT, Feeney RE. Determination of hydrogen sulfide with 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid), N-ethylmaleimide, and parachloromercuribenzoate. Anal Biochem. 1977;79:394–405. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svenson A. A rapid and sensitive spectrophotometric method for determination of hydrogen sulfide with 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide. Anal Biochem. 1980;107:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen X, Peter EA, Bir S, Wang R, Kevil CG. Analytical measurement of discrete hydrogen sulfide pools in biological specimens. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:2276–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, Bengtsson A, Leviten D, Hill P, Insko MA, Dumpit R, VandenEkart E, Toombs CF, Szabo C. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu C, Pan J, Li S, Zhao Y, Wu LY, Berkman CE, Whorton AR, Xian M. Capture and visualization of hydrogen sulfide by a fluorescent probe. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:10327–10329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu C, Peng B, Li S, Park CM, Whorton AR, Xian M. Reaction based fluorescent probes for hydrogen sulfide. Org Lett. 2012;14:2184–2187. doi: 10.1021/ol3008183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qian Y, Karpus J, Kabil O, Zhang SY, Zhu HL, Banerjee R, Zhao J, He C. Selective fluorescent probes for live-cell monitoring of sulphide. Nat Commun. 2011;2:495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang XF, Wang L, Xu H, Zhao M. A fluorescein-based fluorogenic and chromogenic chemodosimeter for the sensitive detection of sulfide anion in aqueous solution. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;631:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshida E, Toyama T, Shinkai Y, Sawa T, Akaike T, Kumagai Y. Detoxification of methylmercury by hydrogen sulfide-producing enzyme in Mammalian cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1633–1635. doi: 10.1021/tx200394g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishida M, Sawa T, Kitajima N, Ono K, Inoue H, Ihara H, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Suematsu M, Kurose H, van der Vliet A, Freeman BA, Shibata T, Uchida K, Kumagai Y, Akaike T. Hydrogen sulfide anion regulates redox signaling via electrophile sulfhydration. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:714–724. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Filipovic MR, Miljkovic JL, Nauser T, Royzen M, Klos K, Shubina T, Koppenol WH, Lippard SJ, Ivanovic-Burmazovic I. Chemical characterization of the smallest S-nitrosothiol, HSNO; cellular cross-talk of H2S and S-nitrosothiols. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12016–12027. doi: 10.1021/ja3009693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paul BD, Snyder SH. H2S signalling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:499–507. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sen N, Snyder SH. Protein modifications involved in neurotransmitter and gasotransmitter signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toohey JI. The conversion of H2S to sulfane sulfur. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:803. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cahn RS, Dermer OC. Introduction to Chemical Nomenclature. 5. Butterworth; Woburn, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ubuka T. Assay methods and biological roles of labile sulfur in animal tissues. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;781:227–249. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wood JL. Sulfane sulfur. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toohey JI. Sulphane sulphur in biological systems: a possible regulatory role. Biochem J. 1989;264:625–632. doi: 10.1042/bj2640625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jacob C, Anwar A, Burkholz T. Perspective on recent developments on sulfur-containing agents and hydrogen sulfide signaling. Planta Med. 2008;74:1580–1592. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Munchberg U, Anwar A, Mecklenburg S, Jacob C. Polysulfides as biologically active ingredients of garlic. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:1505–1518. doi: 10.1039/b703832a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gliubich F, Gazerro M, Zanotti G, Delbono S, Bombieri G, Berni R. Active site structural features for chemically modified forms of rhodanese. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21054–21061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gliubich F, Berni R, Colapietro M, Barba L, Zanotti G. Structure of sulfur-substituted rhodanese at 1.36 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:481–486. doi: 10.1107/s090744499701216x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hol WG, Lijk LJ, Kalk KH. The high resolution three-dimensional structure of bovine liver rhodanese. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1983;3:370–376. doi: 10.1016/s0272-0590(83)80007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ploegman JH, Drent G, Kalk KH, Hol WG. Structure of bovine liver rhodanese. I. Structure determination at 2.5 A resolution and a comparison of the conformation and sequence of its two domains. J Mol Biol. 1978;123:557–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ploegman JH, Drent G, Kalk KH, Hol WG. The structure of bovine liver rhodanese. II. The active site in the sulfur-substituted and the sulfur-free enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1979;127:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin YJ, Dancea F, Lohr F, Klimmek O, Pfeiffer-Marek S, Nilges M, Wienk H, Kroger A, Ruterjans H. Solution structure of the 30 kDa polysulfide-sulfur transferase homodimer from Wolinella succinogenes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1418–1424. doi: 10.1021/bi0356597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.You Z, Cao X, Taylor AB, Hart PJ, Levine RL. Characterization of a covalent polysulfane bridge in copper-zinc superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1191–1198. doi: 10.1021/bi901844d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bordo D, Bork P. The rhodanese/Cdc25 phosphatase superfamily. Sequence-structure-function relations. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:741–746. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cipollone R, Ascenzi P, Visca P. Common themes and variations in the rhodanese superfamily. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:51–59. doi: 10.1080/15216540701206859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hofmann K, Bucher P, Kajava AV. A model of Cdc25 phosphatase catalytic domain and Cdk-interaction surface based on the presence of a rhodanese homology domain. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:195–208. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Theodosiou A, Ashworth A. MAP kinase phosphatases. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS3009. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-reviews3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Agro AF, Mavelli I, Cannella C, Federici G. Activation of porcine heart mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase by zero valence sulfur and rhodanese. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;68:553–560. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)91181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bonomi F, Pagani S, Cerletti P, Cannella C. Rhodanese-Mediated sulfur transfer to succinate dehydrogenase. Eur J Biochem. 1977;72:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Branzoli U, Massey V. Evidence for an active site persulfide residue in rabbit liver aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:4346–4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Conner J, Russell PJ. Elemental sulfur: a novel inhibitor of adenylate kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;113:348–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)90472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Beus MD, Chung J, Colon W. Modification of cysteine 111 in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase results in altered spectroscopic and biophysical properties. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1347–1355. doi: 10.1110/ps.03576904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Edmondson D, Massey V, Palmer G, Beacham LM, III, Elion GB. The resolution of active and inactive xanthine oxidase by affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:1597–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Francoleon NE, Carrington SJ, Fukuto JM. The reaction of H2S with oxidized thiols: Generation of persulfides and implications to H2S biology. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;516:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kato A, Ogura M, Suda M. Control mechanism in the rat liver enzyme system converting L-methionine to L-cystine. 3. Noncompetitive inhibition of cystathionine synthetase-serine dehydratase by elemental sulfur and competitive inhibition of cystathionase-homoserine dehydratase by L-cysteine and L-cystine. J Biochem. 1966;59:40–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim EJ, Feng J, Bramlett MR, Lindahl PA. Evidence for a proton transfer network and a required persulfide-bond-forming cysteine residue in Ni-containing carbon monoxide dehydrogenases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5728–5734. doi: 10.1021/bi036062u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Massey V, Edmondson D. On the mechanism of inactivation of xanthine oxidase by cyanide. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:6595–6598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Massey V, Williams CH, Jr, Palmer G. The presence of S degrees-containing impurities in commercial samples of oxidized glutathione and their catalytic effect on the reduction of cytochrome c. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;42:730–738. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pestana A, Sols A. Reversible inactivation by elemental sulfur and mercurials of rat liver serine dehydratase and certain sulfhydryl enzymes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;39:522–529. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sandy JD, Davies RC, Neuberger A. Control of 5-aminolaevulinate synthetase activity in Rhodopseudomonas spheroides a role for trisulphides. Biochem J. 1975;150:245–257. doi: 10.1042/bj1500245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Taniguchi T, Kimura T. Role of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the formation of the iron-sulfur chromophore of adrenal ferredoxin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;364:284–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(74)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tomati U, Matarese R, Federici G. Ferredoxin activation by rhodanese. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:1703–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tomati U, Giovannozzi-Sermanni G, Duprè S, Cannella C. NADH: Nitrate reductase activity restoration by rhodanese. Phytochemistry. 1976;15:597–598. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Valentine WN, Toohey JI, Paglia DE, Nakatani M, Brockway RA. Modification of erythrocyte enzyme activities by persulfides and methanethiol: possible regulatory role. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1394–1398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Beinert H. A tribute to sulfur. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5657–5664. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kessler D. Enzymatic activation of sulfur for incorporation into biomolecules in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:825–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mueller EG. Trafficking in persulfides: delivering sulfur in biosynthetic pathways. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nchembio779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Toohey JI. Persulfide sulfur is a growth factor for cells defective in sulfur metabolism. Biochem Cell Biol. 1986;64:758–765. doi: 10.1139/o86-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kimura Y, Mikami Y, Osumi K, Tsugane M, Oka JI, Kimura H. Polysulfides are possible H2S-derived signaling molecules in rat brain. FASEB J. 2013;27:2451–2457. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-226415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fu Z, Liu X, Geng B, Fang L, Tang C. Hydrogen sulfide protects rat lung from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2008;82:1196–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]