Abstract

Past research shows that adults often display poor memory for racially-ambiguous and racial outgroup faces, with both face types remembered worse than own-race faces. The present study examined whether children also show this pattern of results. It also examined whether emerging essentialist thinking about race predicts their memory for faces. Seventy-four White children (ages 4–9) completed a face-memory task comprised of White, Black, and racially-ambiguous Black/White faces. Essentialist thinking about race was also assessed (i.e., thinking of race as immutable and biologically based). White children who used essentialist thinking showed the same bias as White adults—they remembered White faces significantly better than ambiguous and Black faces. However, children who did not use essentialist thinking remembered both White and racially-ambiguous faces significantly better than Black faces. This finding suggests a specific shift in racial thinking wherein the boundaries between racial groups become more discrete, highlighting the importance of how race is conceptualized in judgments of racially-ambiguous individuals.

Keywords: own-race bias, racially-ambiguous, face memory, racial essentialism

Although race is a socially-constructed category used to sort humans into distinct groups, people often treat this category as naturally existing (e.g., Markus, 2008). People frequently construe race as biologically-based and immutable, and ascribe inherent meaning to these categories based on physical characteristics associated with racial groups (Rothbart & Taylor, 1992). In adults, such essentialist thinking about race has been shown to lead to prejudice and decreased motivation to cross racial boundaries (e.g., Haslam, Rothschild, & Ernst, 2002; Jayaratne et al., 2006; Keller, 2005; Levy, Stroessner, & Dweck, 1998; Williams & Eberhardt, 2008; Yzerbyt, Rocher, & Schadron, 1997). However, only a handful of studies have explored the social consequences of essentialist thinking in children. Here, we aimed to examine whether children’s emerging essentialist thinking about race has consequences for their memory for faces at the boundary of race (i.e., racially-ambiguous faces).

Essentialist thinking is grounded in the belief that certain categories have important underlying essences that define their nature (Gelman, 2003; Medin & Ortony, 1989). Developmental work on psychological essentialism has demonstrated that children exhibit essentialist thinking about both biological animal categories (e.g., Gelman & Wellman, 1991) and a specific subset of social categories (e.g., race and gender; Hirschfeld, 1995; Rhodes & Gelman, 2009; Taylor, 1996) as early as age 4. Essentialism has been defined in a variety of ways in the literature (see Gelman, 2003; Medin & Ortony, 1989, for reviews), but essentialist thinking about social categories is thought to possess two main components: inalterable membership and inductive potential (Rothbart & Taylor, 1992). Although there are many aspects of essentialism, here, we focus on the implications of one component of essentialist thinking—the perception of the inalterability of group membership—within the domain of race. We examined several features that are consistently viewed as central to essentialist beliefs—that racial categories are viewed as stable, unchanging, likely to be present at birth, and biologically based.

Children appear to essentialize some social categories more readily than others. Although one study found that children at age 4 readily essentialize gender but not race (Rhodes & Gelman, 2009), evidence regarding precisely when children begin to exhibit racial essentialism remains inconclusive. Some studies suggest that children exhibit components of essentialist thinking about race, such as understanding biological inheritance, as early as 4 years (e.g., Hirschfeld, 1995), while others argue that a more coherent essentialist outlook does not emerge until considerably later in childhood (e.g., Aboud, 1984; Pauker, Ambady, & Apfelbaum, 2010; Rhodes & Gelman, 2009). Furthermore, the extent to which children essentialize race seems to vary based on the task (e.g., Gimenez & Harris, 2002; Kinzler & Dautel, 2011) and on the cultural context (Rhodes & Gelman, 2009). Here, we examined essentialist thinking across a wide age-range (4–9 years). We expected that children’s essentialist thinking about race should observably change over this age-range and permit exploration of its role in social perception. Thus, examining this age-range should adequately capture variability in children’s emerging essentialist thinking and the potential implications of these beliefs for children’s memory for faces at the boundary of race.

Racial essentialism is a multi-faceted construct encompassing social, cultural, and cognitive components that impact perception, mental representation, and judgment. For example, some studies have linked essentialist thinking to children’s endorsement and use of racial stereotypes (Levy & Dweck, 1999; Pauker et al., 2010). Accordingly, essentialist thinking likely plays a role in more basic aspects of children’s social cognition, such as how children perceive racial group boundaries. Work with adults indicates that essentialized categories have absolute rather than graded memberships (Kalish, 2002) and possess discrete boundaries (Haslam, Rothschild, & Ernst, 2000). While representing categories as fundamentally distinct is important for learning about objective distinctions between different categories (e.g., “that is a dog, not a cat”), essentialist thinking can be problematic when applied to social categories. When applied to race, essentialism promotes the belief that subjective racial categories are objective and natural, exaggerating distinctions between groups and minimizing the considerable variation in appearance that exists within and at the boundaries of racial groups (e.g., Freeman, Pauker, Apfelbaum, & Ambady, 2010; Maddox & Gray, 2002). Thus, essentialist thinking promotes the perception that the boundaries between racial groups are clear (Plaks, Malahy, Sedlins, & Shoda, 2012), when in reality there is considerable variation and ambiguity.

To this point, we have considered the role of essentialist thinking in judgments regarding individuals who are perceived as clear and unambiguous members of a racial category. However, essentialist thinking should be particularly important when there is some question about group membership—as in the case of racially-ambiguous individuals—who are not easily categorized by race due to the racial ambiguity of their features (Pauker, Rule, & Ambady, 2010). Throughout U.S. history, the principle of hypodescent has been used to assign mixed-race individuals to their socially subordinate group. For example, early in American history, White slave owners used the one-drop rule—whereby one drop of Black blood identified an individual as Black—to disambiguate mixed-race individuals, and as a result consigned thousands to slavery (Davis, 1991). Despite the fact that institutionalized practices of the one-drop rule have been banished, the principle of hypodescent continues to influence American adults’ racial categorization (Halberstadt, Sherman, & Sherman, 2011; Ho, Sidanius, Levin & Banaji, 2011; Peery & Bodenhausen, 2008). This greater tendency to categorize racially-ambiguous individuals as belonging to their socially subordinate group is particularly true for adults who endorse racial essentialism to a greater degree (Chao, Hong, & Chiu, 2013). Levels of essentialist thinking also predict adults’ reliance on discrete racial category labels when processing and trying to remember racially-ambiguous faces in comparison to processing unambiguous faces (Eberhardt, Dasgupta, & Banaszynski, 2003; Pauker & Ambady, 2009). Finally, racially-ambiguous faces are less likely to be accurately remembered in comparison to racially-unambiguous ingroup faces (e.g., Corneille, Huart, Becquart, & Brédart, 2004; Pauker et al., 2009). These results are consistent with the well-documented own-race bias in which perceivers are better at remembering ingroup compared to outgroup faces (e.g., Hugenberg, Young, Bernstein, & Sacco, 2010; Meissner & Brigham, 2001). In the case of racially-ambiguous group members, the tendency to exclude racially-ambiguous individuals from the ingroup and to frequently classify them as outgroup, leads to poorer memory for racially-ambiguous faces (Pauker et al., 2009). Moreover, differences in racial essentialism do not appear to predict memory for individuals who can clearly be classified into groups, but do predict memory for racially-ambiguous faces (Pauker, Weisbuch, & Ambady, 2011).

Thus we propose that children’s emerging racial essentialism should be associated with perceiving racial categories as fundamentally distinct and should predict poorer memory for racially-ambiguous faces compared to clearly ingroup faces. To test this idea, we adapted a recognition memory paradigm used with adults (Pauker et al., 2009) to assess memory for White, Black and racially-ambiguous Black/White faces among White children 4–9 years in age—the age-range in which White children typically begin to exhibit racial essentialism. We hypothesized that the degree to which children exhibit use of racial essentialism should be associated with a view of race as less continuous and more categorical, ultimately manifesting in poorer memory for racially-ambiguous faces.

The own-race bias (i.e., better memory for ingroup compared to outgroup faces) is well formed among White children 4–9 years (e.g., Chance, Turner & Goldstein, 1982; Sangrigoli & de Schonen, 2004a) and appears stable in this population from 6 years (De Heering, De Liedekerke, Deboni, & Rossion, 2010). This work suggests that children, like adults, should exhibit the typical own-race bias for clear racial group members, but is silent with regards to children’s memory for racially-ambiguous faces. We predicted children’s essentialist thinking should be related to their memory for racially-ambiguous but not unambiguous ingroup or outgroup faces. Specifically, we predicted that White children who do not use essentialist reasoning about race would remember both White and racially-ambiguous faces better than Black faces because they would view ambiguously-raced faces—which straddle the White/Black color line—more flexibly. On the other hand, we predicted that those who utilized essentialist reasoning about race would adhere to more rigid distinctions regarding racial groups and would exhibit superior recognition for White faces over both racially-ambiguous and Black faces.

Method

Participants and Design

A total of 89 White children were recruited from two schools and a museum science center in the greater Boston area. Parents were informed about the study including its focus on racial perceptions either from a letter sent home by the school administration (35% response rate), or through an in-person invitation to participate at the science center (80% response rate). We used an a priori exclusion criterion based on the idea that children who showed memory at chance levels across all face types during the memory task were either not paying attention or found the task was too difficult. Thus, data from 13 participants were excluded. Additionally 2 other children were excluded who used a response pattern (i.e., alternating right face, left face) during the recognition phase. These exclusions resulted in a final sample of 74 White children (45 female) between the ages of 4–9 years (M = 5.96, SD = 1.50). Children were recruited from two schools (n = 21) and from a local science museum (n = 53). Based on parent-reported demographics from the schools and the science center’s data on the average visitor to their center, approximately 64% of our participants were from families earning $75,000 or more a year and approximately 73% were from families whose parents had at least a college degree.

The study used a 3 (Race of Target Face: White, Black, and ambiguous) x 2 (Racial Essentialism: yes or no) mixed-model design with repeated measures on the first factor.

Measures and Procedure

For participants recruited from schools, parents were asked to complete an optional demographic form that asked them to specify their child’s racial background. At the science center, parents were asked this question in-person. After receiving parental consent, the experimenter asked for children’s verbal assent and made clear that they could stop the study at any point. Children completed the study on a computer that was located separate from the classroom or separate from other children at the science center. Each participant completed two tasks: a face memory task and a racial essentialism assessment. To avoid carry-over effects from tasks that were specifically about race (e.g., racial essentialism), the memory task always came first to minimize suspicion about the hypothesis.

Memory task

We used the face recognition procedure used in Pauker et al. (2009) on adults, but with fewer faces to make it easier for children. Participants were told that they were going to play a memory game and that they would receive stickers in exchange for participating. The experimenter told the children to pay close attention to each face and explained that they would be asked to say which faces they had seen before.

A subset of Pauker and colleagues’ (2009) computer-generated White, Black and racially-ambiguous (Black/White) adult faces was used as stimuli. All of the faces were previously pre-tested to ensure they were prototypical of White or Black faces or fell in-between and were perceived as “truly ambiguous.” All the faces depicted neutral facial expressions and were equated for attractiveness (see Pauker et al., 2009). Faces varied with respect to both skin-color and other features prototypically associated with White and Black faces (e.g., shape of lips). The task included two phases. During the learning phase, participants viewed 4 White faces, 4 Black faces, and 4 ambiguous Black/White faces (hereafter called target faces). An equal number of male and female faces were included in each racial category. Each target face was adjusted to uniform size and resolution (500 × 500 pixels; 3.5 × 3 inches; 153 pixels/inch) and was shown in a randomized order for 5000 ms, followed by a fixation cross with an inter-trial interval of 1010 ms.

After completing the learning phase, participants were asked a few distracter questions (e.g., “What are you doing this weekend? What have you seen at the museum so far?”). In the recognition phase, participants were shown the 12 target faces from the learning phase in addition to 12 foil faces: 4 White, 4 Black, and 4 racially-ambiguous, all of which were gender-balanced. The foil faces were shown next to a target face of the same race and gender and these pairings were displayed in a random order. During the recognition phase, children were instructed that they would see two faces, one on the right side and one on the left side of the screen and that they should both point to the face that they had seen before and press the “L” key if the face was on the left and the “R” key if the face was on the right. These keys were clearly labeled with stickers to minimize confusion. No feedback on accuracy was provided. The dependent measure of interest was recognition memory (measured by d’).

Racial essentialism

After the memory task, participants completed a short three-item racial essentialism measure adapted from previous tasks used to examine children’s beliefs about immutability of category membership (Hirschfeld, 1995; Ruble et al., 2007; Semaj, 1980). Participants were first shown three faces (all photos were matched to the child’s gender): one was either a Black or White child whose photo was placed above that of a Black adult and a White adult. The experimenter asked: “When this child grows up, will they look more like this adult [White] or that adult [Black]?” (the order of the adult photos was counterbalanced across all participants). Next, participants viewed a similar picture array except they saw either a Black or White adult pictured above a Black child and a White child (in counterbalanced order). The experimenter then asked: “When this adult was little, did they look more like this child [White] or that child [Black]?” Finally, the experimenter pointed to a picture of a White child and asked, “If this child really wanted to be Black and change his/her skin color could he/she do that?” Children were then asked to explain why they believed that the child could or could not change his or her racial group membership to uncover their reasoning. Children were categorized as having essentialist thinking about race if they: a) correctly made a race match in the first two questions and answered “no” to the last question, indicating that they believe race is both stable across the lifespan and immutable, and b) utilized essentialist reasoning in their explanation for why someone could not change their skin color by referencing either immutability (e.g., “black skin stays forever”), inheritability/biology (e.g., “you stay the same because you are born that way”) or naturalness (e.g., “can’t change his skin, he was made that way”; see Pauker et al., 2010 and Ruble et al., 2007 for similar methods and coding strategies). If children did not provide reasoning for their answer or if that reasoning did not fall into any of the above categories (i.e., reasoning such as “they like being that way”), children were coded as non-racially-essentialist. In other words, children needed to answer all questions correctly and provide essentialist reasoning to be coded as having racial essentialism.

Hirschfeld (1995) argues that some work underestimates children’s understanding of race as an unchanging, biologically-based category because it utilizes hard-to-understand tasks. In order to avoid such issues we modeled our measure on those that examine natural changes over the lifespan (i.e., growth) with a couple of key additions. First, we used real pictures as our stimuli. Past research has mostly used drawings (e.g., Gimenez & Harris, 2002; Hirschfeld, 1995), which may limit the generalizability of the findings (e.g., maybe children do not conceptualize drawings in the same way that they do actual people). Second, we probed for children’s self-produced reasoning about whether a change in racial group membership is possible and coded for explanations consistent with essentialist beliefs: that a category is stable, unchanging, likely to be present at birth, natural, and biologically based. Examining children’s social reasoning in this way provides valuable insight into children’s understandings of concepts not available through simple forced-choice measures (e.g., Gimenez & Harris, 2002; Killen & Stangor, 2001; Taylor, Rhodes, & Gelman, 2009). This measure of racial essentialism has been used in past research, and reliably relates to children’s racial stereotyping (Pauker et al., 2009). Based on this task, children were divided into two groups: non-essentialist and essentialist. After all the tasks were completed, children chose some stickers in exchange for participating.

Results

Data Transformation

We calculated d’ scores using the proportion of correct choices from the face recognition task. Since this was a two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) paradigm, we used the following formula to calculate d’: z score [proportion correct]*√2 (Macmillan & Creelman, 2005). When proportion correct is equal to 1 or 0, no z score can be calculated; therefore we calculated corrected proportions based on the number of signal or noise trials (n = 4; Stanislaw & Todorov, 1999). When the proportion correct equaled zero, the value was recoded as 0.5/n, and when the proportion correct equaled one, the value was recoded as 1 - (0.5/n). No differences were found relating either to participant gender or the gender of stimuli so analyses were collapsed across these variables.

Recognition Performance and Racial Essentialism

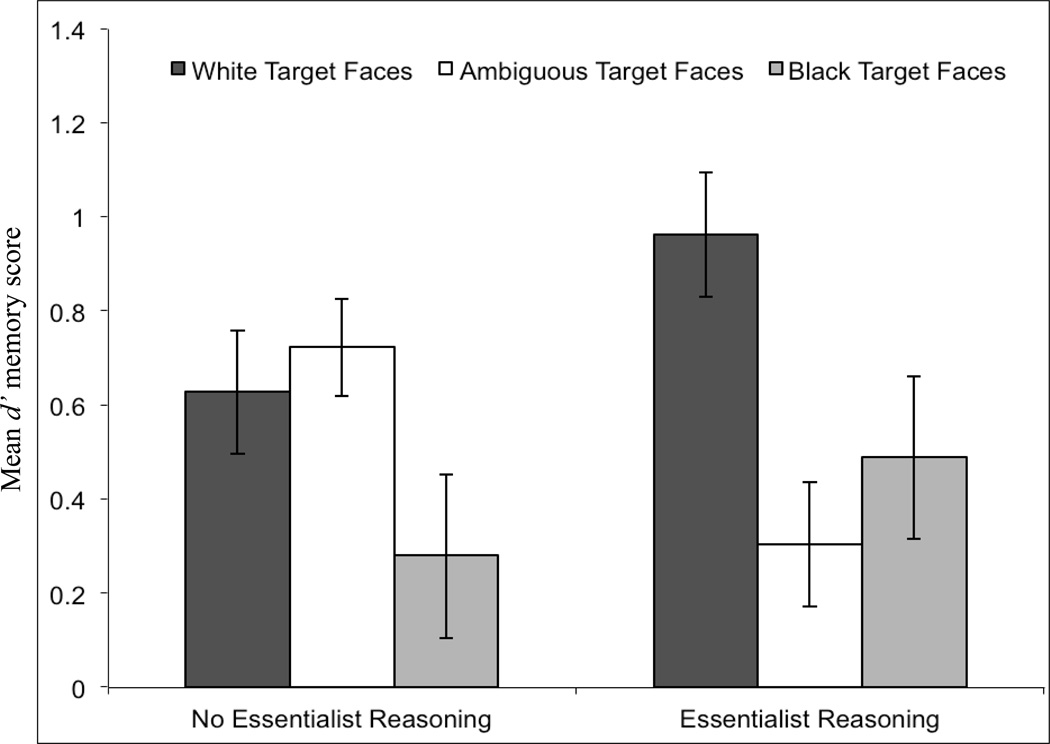

To test our hypotheses, we compared memory for the target faces between children with essentialist reasoning (n = 35, 19 female) and those without essentialist reasoning (n = 39, 26 female). We ran a 3(Target Race: White, Black, and ambiguous) × 2(Racial Essentialism: yes or no) mixed-model ANOVA on the measure of face recognition memory: the mean d’ scores. There was a significant interaction between target race and racial essentialism, F(2, 144) = 3.76, p < .03, η2 = .050, and a main effect only for target race, F(2,144) = 4.06, p < .02, η2 = .053 (see Figure 1). In order to further examine the differences in memory associated with essentialist thinking, planned contrasts were conducted on the d’ scores for White, Black, and racially-ambiguous faces for children with and without racial essentialist reasoning. As predicted (and similar to adults in prior research), children with essentialist beliefs remembered White faces (M = .96, SD = .78) significantly better than both ambiguous (M = .30, SD = .78) and Black faces (M = .49, SD = 1.0), t(144) = 3.05, p <.002, r = .25. In comparison, children without essentialist beliefs remembered both White (M = .63, SD = .82) and ambiguous (M = .72, SD = .64) faces better than Black faces (M = .28, SD = 1.1), t(144) = 2.25, p < .02, r = .18. Furthermore, children without essentialist beliefs recognized ambiguous faces significantly better than children with essentialist beliefs, t(144) = 2.01, p < .03, r = .17.

Figure 1.

Mean d’ memory score by target face race for children without and with essentialist reasoning about race. Error bars denote standard error.

We examined race essentialism and memory over a wide age range, under the assumption that we should find considerable variability in race essentialism in this age-range, presumably with more essentialist reasoning occurring as children got older. We found only moderate support for this premise. While there was variability in essentialist reasoning in this age-range, there were no significant differences in the average age of children who exhibited (M = 6.13, SD = 1.16) or did not exhibit (M = 5.80, SD = 1.75) essentialist reasoning. Based on prior research that found 6-year-olds typically displayed essentialist reasoning (Pauker et al., 2010), we also compared use of essentialism in 4–5 year-olds and 6–9 year-olds. A greater proportion of older (6–9 year-old) children (60.5%) used essentialism compared to younger (4–5 year-old) children (29%), χ2 (1) = .714, p = .008. Together with the prior analysis, support for clear age-differences in essentialist reasoning in our study is inconclusive at best. Importantly, however, an additional analysis controlling for age as a variable did not change any of the above memory effects nor did it interact with racial essentialism or target race of the stimuli.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to relate essentialist thinking about race to memory for racially-ambiguous faces among children. As hypothesized, the emergence of racial essentialist reasoning in White children was associated with significant decrements in memory for racially-ambiguous faces. Linking this to perception, as White children start to essentialize race, they are more likely to perceive racial boundaries as distinct, decreasing their ability to recognize racially-ambiguous faces. This highlights one social cognitive pathway that may contribute to the development of the own-race bias as it applies toward racially-ambiguous faces: changes in conceptions of race. Although alternative interpretations of the relationship between racial essentialism and memory are possible, we argue that as children become less flexible in how they think about social categories, they come to perceive racially-ambiguous faces equivalently to other racial outgroup faces, resulting in their poorer recognition. Our results replicate past studies with White children in that the own-race bias was robust for unambiguous ingroup and outgroup members which converges with findings in adults—essentialist beliefs seem to only affect memory for those at the boundaries of group membership.

The results of this study supplement earlier findings whereby adults who score high on measures of essentialism remember racially-ambiguous and clearly outgroup faces equally poorly (Pauker & Ambady, 2009; Pauker et al., 2011). Our results indicate that children without racial essentialism view racially-ambiguous faces as more similar to their ingroup, since they recognize them better than clearly outgroup, Black faces. But after adopting a more essentialist perspective towards race, White children’s category boundaries sharpen and become more distinct, and ambiguous faces become recognized less accurately. Future studies should explore specifically how racially-ambiguous faces are processed differently as a result of emerging racial essentialism in addition to investigating the development of how children learn to distinguish both racial ingroup and outgroup members and racially-ambiguous populations.

What is clear is that after attaining beliefs that the physical characteristics associated with race are stable, immutable, and biologically based, there is greater differentiation in memory between the ingroup and racially-ambiguous targets. Perhaps obtaining a racial essentialist outlook not only marks a decline in the recognition of ambiguous faces, but also marks a more clear delineation between the ingroup and all other groups. This possibility is supported by the fact that children with essentialist reasoning had the best recall for White faces overall. Past research has found that children’s memory for ambiguous faces depends on a combination of perceptual features seen in the face and categorical knowledge that can influence the resolution of racial group membership (Shutts & Kinzler, 2007). Here, we argue that children may use this categorical information to a greater degree as they acquire essentialist thinking.

Alternatively, one might question why non-essentialist children would have different memory performance for ingroup and outgroup faces at all. In other words, if a child is non-essentialist one could argue that this would indicate that the child should also not essentialize race for more prototypical outgroup members either (i.e., Black faces). Therefore, children’s categorization of racially-ambiguous faces as White or ingroup could be seen as just as essentialist as categorizing them as Black or the outgroup. But it is known that White infants and children quickly develop a pro-White bias in visual and memory preferences very early on in development, demonstrating that infants and young children appear to be adept at picking up ingroup and outgroup cues for easily identifiable group members even before they develop essentialist notions of race. It is true that higher memory for racially-ambiguous faces could be interpreted as a higher tolerance for who is considered ingroup in our study, but from our perspective that is consistent with our argument. Racial essentialism impacts individuals’ perceptions of their group boundaries and tolerance for including racially-ambiguous individuals into the ingroup, which has direct implications for memory. We believe that categorizing faces as one’s ingroup does not necessarily imply that these White children are categorizing the faces explicitly as White, but rather they are more likely to process them as more relevant to the self rather than merely disregarding those faces in memory. Furthermore, we do not have data to support whether children are simply categorizing racially-ambiguous faces as another race. Therefore, we do not know if children are categorizing racially-ambiguous faces explicitly as monoracial Black or White faces. We only know that children’s memory performance for racially-ambiguous faces is not significantly different from that of monoracial Black faces or White faces depending on whether they have adopted an essentialist view of race or not. This is something that we believe future research should address—what explicit labels do children apply to racially-ambiguous faces and how does that affect perception and memory?

Although we focused here on the link between racial essentialism and memory for same-race, other-race, and racially-ambiguous faces, other factors may also contribute to children’s face recognition abilities. Children’s experience with other-race faces has been shown to predict their facial memory for unambiguous racial groups. Infants and children who are exposed to additional exemplars of other-race faces (e.g., Heron-Delaney et al., 2011; Sangrigoli & de Schonen, 2004b), who live in more racially-mixed neighborhoods, or who attend more integrated schools show a decrease in the own-race bias (Cross, Cross & Daly, 1971; Feinman & Entwisle, 1976; Gaither, Pauker, & Johnson, 2012; Sangrigoli, Pallier, Argenti, Ventureyra, & de Schonen, 2005). Therefore, children’s lack of exposure to ambiguous and other-race faces may affect these outcomes. Although our sample included children who grew up in urban and racially diverse environments, future research should further explore this question.

Minority children might also show different patterns of memory because their differential awareness of race may affect when racial essentialism emerges (e.g., Kinzler & Dautel, 2012; Phinney, 1992; Rockquemore & Laszloffy, 2005). Additionally, past studies have also found slightly weaker own-race bias effects in minority children in comparison to White children (e.g., Cross et al., 1971; Feinman & Entwisle, 1976). Multiracial children may also differ in terms of their patterns of memory, since they might be likely to develop less essentialist beliefs about race. Research with adults has found that biracial adults endorse less essentialist thinking than their monoracial counterparts (Bonam & Shih, 2009; Pauker & Ambady, 2009; Shih, Bonam, Sanchez, & Peck, 2007). Clearly, in order to gain a more complete picture of the role racial essentialism plays in children’s memory for racially-ambiguous and outgroup faces, future research will need to examine participants from a wider range of racial identities. Additionally, the majority of our participants were from upper-middle to upper-class families, so future work should also examine whether these results generalize to children from other socio-economic backgrounds.

Finally, the present work specifically examined memory performance for White, Black, and racially-ambiguous Black/White faces. We selected these groups for this study because the specific history of Black/White relations in the U.S. makes Black individuals a highly salient racial category for White children around which they readily form implicit biases (Baron & Banaji, 2006). However, it is unclear whether racial essentialism would relate to children’s memory in a similar manner for other types of racially-ambiguous faces. Research with adults shows that the boundary for categorizing faces as White or minority depends on the current racial hierarchy in the U.S., such that individuals must have considerably more evidence to categorize a Black/White biracial individual as White compared to an Asian/White biracial individual (Ho et al., 2011). Based on these findings with adults, it is entirely possible that the current results might be less pronounced, if we examined children’s memory for Asian/White racially-ambiguous faces. However, this conjecture is in need of direct empirical assessment.

Complementing the role of emerging racial essentialism in the onset of stereotype use and more biased attitudes (e.g., Pauker et al., 2010; Ruble et al., 2004; Semaj, 1980), our findings demonstrate that emerging racial essentialism likely relates to more basic social perceptions of race: poor memory for racially-ambiguous faces in children (an effect that resembles biases seen in adulthood; e.g., Pauker et al., 2009). Racial essentialist reasoning negatively predicts memory for racially-ambiguous individuals, and children overlook racially-ambiguous individuals in memory to the same extent as other outgroup members. These facts highlight the need for additional research on the perception and judgment of racially-ambiguous children—one of the fastest growing populations in contemporary society.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Living Laboratory at the Museum of Science, Boston, the Tufts Educational Day Care Center, and the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School for recruitment assistance and all of the families for participating. This work was supported by a NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and a Tufts Graduate Research Award, both awarded to Sarah Gaither, a National Institute of Child Development award (K99HD065741-02) granted to Kristin Pauker, and a grant from the Russell Sage Foundation awarded to Samuel Sommers.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Gaither, Department of Psychology, Tufts University

Jennifer R. Schultz, Department of Psychology, Tufts University

Kristin Pauker, Department of Psychology, University of Hawaii.

Samuel R. Sommers, Department of Psychology, Tufts University

Keith B. Maddox, Department of Psychology, Tufts University

Nalini Ambady, Department of Psychology, Stanford University.

References

- Aboud FE. Social and cognitive bases of ethnic identity constancy. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1984;145:217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Baron AS, Banaji MR. The development of implicit attitudes: Evidence of race evaluations from ages 6, 10, and adulthood. Psychological Science. 2006;17:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian B, Haslam N. Psychological essentialism and stereotype endorsement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich J, Wyer NA, Swart LA, Kibler JL. Racism and racial categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1364–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Bonam C, Shih M. Exploring multiracial individuals’ comfort with intimate interracial relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 2009;65:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chance JE, Turner AL, Goldstein AG. Development of differential recognition for own- and other-race faces. Journal of Psychology. 1982;112:29–37. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1982.9923531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MM, Hong Y, Chiu C. Essentializing race: Its implications on racial categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:619–634. doi: 10.1037/a0031332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneille O, Huart J, Becquart E, Brédart S. When memory shifts toward more typical category exemplars: Accentuation effects in the recollection of ethnically ambiguous faces. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:236–250. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JF, Cross J, Daly J. Sex, race, age, and beauty as factors in recognition of faces. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 1971;6:393–396. [Google Scholar]

- Davis FJ. Who is Black? One nation’s definition. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Deeb I, Segall G, Birnbaum D, Ben-Eliyahu A, Diesendrunk G. Seeing isn’t believing: The effect of intergroup exposure on children’s essentialist beliefs about ethnic categories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:1139–1156. doi: 10.1037/a0026107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Heering ALde, De Liedekerke C, Deboni M, Rossion B. The role of experience during childhood in shaping the other-race effect. Developmental Science. 2010;13:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt JL, Dasgupta N, Banaszynski TL. Believing is seeing: The effects of racial labels and implicit beliefs on face perception. Personalityand Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:360–370. doi: 10.1177/0146167202250215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinman S, Entwisle DR. Children's ability to recognize other children's faces. Child Development. 1976;47:506–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Pauker K, Apfelbaum E, Ambady N. Continuous dynamics in the real-time perception of race. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Gaither SE, Pauker K, Johnson SP. Biracial and monoracial infant own-race face perception: An eye tracking study. Developmental Science. 2012;15:775–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA. The essential child: Origins of essentialism in everyday thought. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA, Wellman HM. Insides and essences: early understandings of the non-obvious. Cognition. 1991;38:213–244. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(91)90007-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez M, Harris PL. Understanding constraints on inheritance: evidence for biological thinking in early childhood. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt J, Sherman SJ, Sherman JW. Why Barack Obama is Black: A cognitive account of hypodescent. Psychological Science. 2011;22:29–33. doi: 10.1177/0956797610390383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Rothschild L, Ernst D. Essentialist beliefs about social categories. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;39:113–127. doi: 10.1348/014466600164363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Rothschild L, Ernst D. Are essentialist beliefs associated with prejudice? British Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;41:87–100. doi: 10.1348/014466602165072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron-Delaney M, Anzures G, Herbert JS, Quinn PC, Slater AM, Tanaka JW, Lee K, Pascalis O. Perceptual training prevents the emergence of the other race effect during infancy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:19858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld LA. Do children have a theory of race? Cognition. 1995;77:1298–1308. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)91425-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AK, Sidanius J, Levin DT, Banaji MR. Evidence for hypodescent and racial hierarchy in the categorization and perception of biracial individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:492–506. doi: 10.1037/a0021562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugenberg K, Young SG, Bernstein MJ, Sacco DF. The categorization-individuation model: An integrative account of the cross race recognition deficit. Psychological Review. 2010;117:1168–1187. doi: 10.1037/a0020463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Racist thinking and thinking about race: What children know but don’t say. Ethos. 1997;25:117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaratne TE, Ybarra O, Sheldon JP, Feldbaum M, Pfeffer CA, Petty EM. White Americans’ genetic lay theories of race differences and sexual orientation: Their relationship with prejudice toward Blacks, and gay men and lesbians. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2006;9:77–94. doi: 10.1177/1368430206059863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalish CW. Essentialist to some degree: Beliefs about the structure of natural kind categories. Memory and Cognition. 2002;30:340–352. doi: 10.3758/bf03194935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J. In genes we trust: The biological component of psychological essentialism and its relationship to mechanisms of motivated social cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:686–702. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Stangor C. Children’s social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer groups contexts. Child Development. 2001;72:174–186. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Dautel JB. Children’s essentialist reasoning about language and race. Developmental Science. 2012;15:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DT, Banaji MR. Distortions in the perceived lightness of faces: The role of race categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2006;135:501–512. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SR, Dweck CS. The impact of children’s static versus dynamic conceptions of people on stereotype formation. Child Development. 1999;70:1163–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Levy SR, Stroessner SJ, Dweck CS. Stereotype formation and endorsement: The role of implicit theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1421–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: A user’s guide. 2nd ed. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox KB, Gray SA. Cognitive representations of Black Americans: Reexploring the role of skin tone. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR. Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity. American Psychologist. 2008;63:651–670. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.8.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medin DL, Ortony A. Psychological essentialism. In: Vosniadou S, Ortony A, editors. Similarity and analogical processing. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner CA, Brigham JC. Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: A meta-analytic review. PsychologyPublic Policy, and Law. 2001;7:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Ambady N. Multiracial faces: How categorization affects memory at the boundaries of race. Journal of Social Issues. 2009;65:69–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Ambady N, Apfelbaum E. Race salience and essentialist thinking in racial stereotype development. Child Development. 2010;81:1799–1813. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Rule NO, Ambady N. Ambiguity and social perception. In: Balcetis E, Lassiter D, editors. The Social Psychology of Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Weisbuch M, Ambady N. I’m comfortable with racial ambiguity when it’s functionally important: Environmental constraints on processing racial ambiguity. In: Savani K, Weisbuch M, editors. Manifest Culture: An Analysis of the Psychological Basis and Influence of Sociocultural Landscapes; San Antonio, TX. Symposium conducted at the 12th Annual Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology.Jan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Weisbuch M, Ambady N, Sommers SR, Adams RB, Jr., Ivcevic Z. Not so Black and White: Memory for ambiguous group members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:795–810. doi: 10.1037/a0013265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peery D, Bodenhausen GV. Black + White = Black: Hypodescent in reflexive categorization of racially ambiguous faces. Psychological Science. 2008;19:973–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Plaks JE, Malahy LW, Sedlins M, Shoda Y. Folk beliefs about human genetic variation predict discrete versus continuous racial categorization and evaluative bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;3:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Gelman SA. A developmental examination of the conceptual structure of animal, artifact, and human social categories across two cultural contexts. Cognitive Psychology. 2009;59:244–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Leslie S, Tworek CM. Cultural transmission of social essentialism. PNAS. 2012;109:13526–13531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208951109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore KA, Laszloffy TA. Raising Biracial Children. Altamira Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Taylor M. Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds. In: Semin GR, Fiedler K, editors. Language and social cognition. London: Sage; 1992. pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Alvarez J, Bachman M, Cameron J, Fuligni A, Coll CG. The development of a sense of “we”: The emergence and implications of children’s collective identity. In: Bennett M, Sani F, editors. The development of the social self. East Sussex: Psychology Press; 2004. pp. 29–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Taylor LJ, Cyphers L, Greulich FK, Lurye LE, Shrout PE. The role of gender constancy in early gender development. Child Development. 2007;78:1121–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, Pallier C, Argenti MA, Ventureyra VAG, de Schonen S. Reversibility of the other-race effect in face recognition during childhood. Psychological Science. 2005;16:440–444. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, de Schonen S. Effect of visual experience on face processing: developmental study of inversion and non-native effects. Developmental Science. 2004a;7:74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, de Schonen S. Recognition of own-race and other-race faces by three month old infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004b;45:1219–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaj LT. The development of racial evaluation and preference: A cognitive approach. The Journal of Black Psychology. 1980;6:59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Shih M, Bonam C, Sanchez D, Peck C. The social construction of race: Biracial identity and vulnerability to stereotypes. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:125–133. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutts K, Kinzler K. An ambiguous-race illusion in children’s face memory. Psychological Science. 2007;18:763–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanislaw H, Todorov N. Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1999;31:137–149. doi: 10.3758/bf03207704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. The development of children’s beliefs about social and biological aspects of gender differences. Child Development. 1996;67:1555–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Rhodes M, Gelman S. Boys will be boys; cows will be cows: Children’s essentialist reasoning about gender categories and animal species. Child Development. 2009;80:461–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MJ, Eberhardt JL. Biological conceptions of race and the motivation to cross racial boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:1033–1047. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzerbyt V, Rocher S, Schadron G. Stereotypes as explanations: A subjective essentialistic view of group perception. In: Spears R, Oakes PJ, Ellemers N, Haslam SA, editors. The Social Psychology of Stereotyping and Group Life. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell; 1997. pp. 20–50. [Google Scholar]