Abstract

Pretreatment changes in alcohol use challenges the assumption that the major portion of the change process occurs after treatment entry. Greater understanding of the behavior change process prior to treatment has the potential to improve our understanding of behavioral changes during treatment. In this study, participants (N = 45) were recruited for a clinical trial examining multiple mechanisms of change in cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence. Using data from both baseline and end of treatment assessments, several pretreatment intervals were created (e.g., a two-week pre-phone call interval, phone call to baseline assessment, baseline assessment to first treatment). To examine pretreatment changes in drinking, percent days abstinent and drinks per drinking day were analyzed using multi-level growth curve modeling and repeated measures ANOVAs. Initial examination of the data revealed significant increases in percent days abstinent and decreases in drinks per drinking day during the pretreatment intervals. Follow-up analyses also suggested that the majority of change in drinking occurs between the phone call and baseline assessment. Further examination of the data revealed two distinct patterns of pretreatment change: a) rapid changers who maintained changes during the course of treatment, and b) gradual changers who changed more gradually during the course of treatment. Analyses revealed that rapid changers had significantly higher rates of abstinence and lower drinks per drinking day at 90 days post-treatment compared to gradual changers. Overall, the data suggest that a more systematic investigation of pretreatment changes in alcohol use is warranted. Future studies may yield insights resulting in more efficient treatment delivery and adaptations to treatment based on an individual’s pretreatment change status.

Keywords: Alcohol, Behavior Change, Mechanism, Pretreatment, Treatment

Changes in addictive behavior frequently take place without professional treatment (Sobell et al., 1991). Indeed, unaided change may be more common than professionally-aided change in the case of alcohol problems (Sobell et al., 1996). Even among those who enter treatment, there is much in their accounts to suggest that a large component of the change process is self-directed (Orford et al., 2006a), with a few studies showing that significant changes in drinking occur prior to the first formal treatment session (e.g., Epstein et al., 2005; Sobell, 2011). As Orford (2006a) notes, these findings suggest that formal treatments are embedded within a much larger system of change-promoting elements occurring before, during, and after formal treatment. Furthermore, these data challenge the assumption that the majority of change occurs after treatment entry and suggests that behavior change must be examined through a broader lens (Willenbring, 2007). Although there is a wealth of research on behavioral change during and after treatment for alcohol use disorders, few studies have focused on pretreatment change, or change that occurs prior to the first formal treatment session. The aim of the current study was to examine changes in pretreatment drinking among those seeking outpatient treatment for alcohol dependence.

In the general psychotherapy literature, studies of pretreatment change have consistently shown significant decreases in symptoms after the initial phone call--when an appointment is scheduled--and before the first treatment session (e.g., Kindsvatter et al., 2010; Lawson, 1994; Ness & Murphy, 2001; West et al., 2011; Weiner-Davis et al., 1987). Similar patterns of change in drinking behaviors have also been reported for those entering treatment for alcohol use disorders. To date, four published reports (Penberthy et al., 2007; Epstein et al., 2005; Kaminer et al., 2008; Morgenstern et al., 2007) and two presentations (Sobell, 2011, Hildebrandt et al., 2011) have reported pretreatment changes in alcohol use within five independent samples. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for many individuals (e.g., 40% to 50%) to achieve abstinence prior to attending their first treatment session (e.g., Epstein et al., 2005). Interestingly, of the two studies to examine predictors of pretreatment change, only one found a positive relationship between alcohol problem severity and pretreatment change (Penberthy et al., 2007). There is also evidence of specific patterns of change (e.g., early rapid changers; Hildebrandt et al., 2011) and better 12-month outcomes for those demonstrating greater pretreatment reductions in the frequency and amount of alcohol consumed (Epstein et al., 2005).

Although assessment reactivity is offered as a possible explanation for the results of several studies (e.g., Epstein et al., 2005; Kaminer et al., 2008), it cannot explain all pretreatment change, as studies show significant change occurring after the initial phone contact and before the first in-person clinical-research assessment (e.g., Epstein et al., 2005; Penberthy et al., 2007; Sobell, 2011). In addition, significant decreases in alcohol consumption are also noted several weeks before the phone call, suggesting that decision-making after seeing an advertisement for treatment may lead to successful behavior change (Sobell, 2011). Moreover, work by Orford and his colleagues (2006a; 2006b) has identified several pretreatment change elements derived from qualitative interviews with clients, including thinking differently about the problem (e.g., weighing pros and cons), receiving encouragement for change from family and friends, a catalyst or clearly identified factor responsible for initiating change (e.g., negative alcohol-related event), the initial phone call, and finally, the baseline assessment. All of these elements are capable of promoting pretreatment changes in alcohol use and several are suggestive of a more natural or self-guided change process.

Taken together, substantial pretreatment changes have implications for 1) how we approach the study of alcohol treatment outcomes, 2) how we conceptualize the role of treatment, particularly for individuals who present to treatment already having made significant changes in their drinking (Orford et al., 2006a; Sobell, 2011), and 3) how we modify treatment delivery for those who evidence substantial pretreatment and early treatment change in alcohol use. Therefore, the current study sought to take a broader look at pretreatment change by including intervals prior to the phone call, phone call to baseline assessment, and baseline assessment to the first treatment session, with the goal of identifying patterns of pretreatment change and how they relate to treatment outcomes.

Method

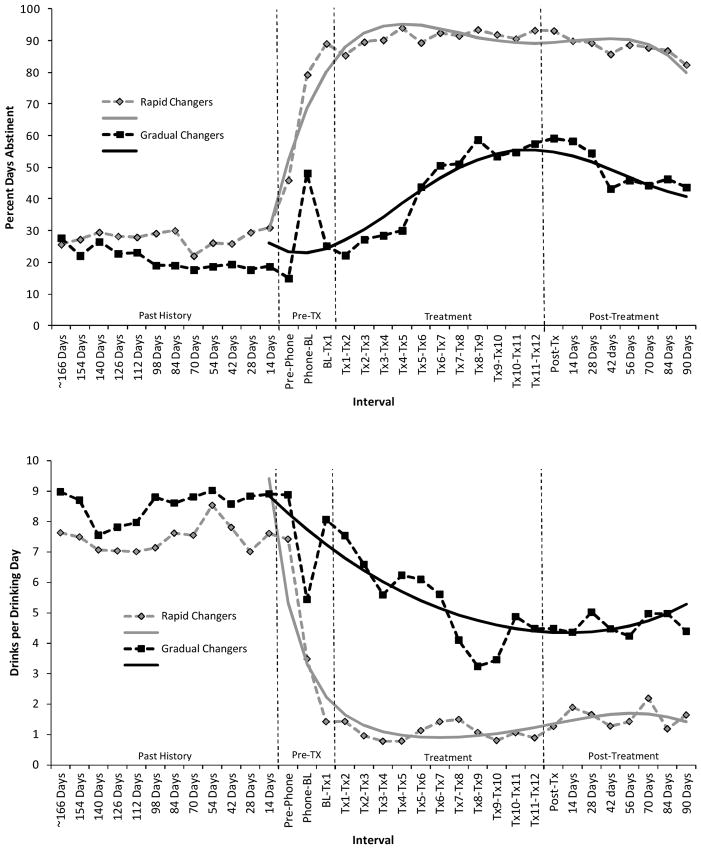

Participants

Participants seeking outpatient treatment for alcohol-related problems were recruited for a parent study investigating multiple mechanisms of change in cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence (CBT). Inclusion criteria were: a) seeking outpatient alcohol treatment services, b) current diagnosis of alcohol dependence, and c) living within commuting distance of the program site. Exclusion criteria included: a) acute psychosis or severe cognitive impairment, b) use of medications (i.e., disulfiram, naltrexone) that may modify alcohol use, c) any current drug use diagnosis other than nicotine or marijuana abuse, and d) legally mandated to attend treatment. Forty-five participants meeting all inclusion and exclusion criteria provided complete data at baseline and post-treatment. Participant recruitment flow is reported in Figure 1 and sample demographics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline assessments for rapid vs. gradual Changers; Mean (SD) or percentages.

| Overall Sample | Rapid (n=24) | Gradual (n=21) | F-test or χ2 | Cohen’s d or Φ (phi) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| % Female | 26.7 (n=12) | 29.2 (n=7) | 23.8 (n=5) | .164 | .06 | .685 |

| % Caucasiana | 86.7 (n=39) | 95.8 (n=23) | 76.2 (n=16) | -- | -- | -- |

| % Employed | 57.8 (n=26) | 45.8 (n=11) | 71.4 (n=15) | 3.01 | .26 | .083 |

| % Married | 64.4 (n=29) | 66.7 (n=16) | 61.9 (n=13) | .11 | .05 | .739 |

| Income | 5.6 (2.5) | 5.7(2.4) | 5.5 (2.6) | .18 | .08 | .672 |

| Age (years) | 48.7 (7.0) | 50.5 (7.0) | 46.7 (6.6) | 3.43 | .56 | .071 |

| Education (years) | 14.7 (2.1) | 14.6 (2.4) | 14.9 (1.8) | .10 | .14 | .756 |

| # Past Outpatient Tx | 1.4 (4.0) | 1.6 (4.9) | 1.1 (2.7) | .16 | .13 | .692 |

| # Tx Sessions | 10.1 (3.3) | 10.6 (3.1) | 9.4 (3.5) | 1.47 | .36 | .232 |

| ADS | 16.0 (7.4) | 16.9 (7.7) | 14.9 (7.0) | .83 | .27 | .368 |

| AASE Total Score | 54.7 (14.0) | 55.6 (15.7) | 53.7 (11.9) | .21 | .14 | .649 |

| PANAS | ||||||

| Positive Affect | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | .48 | .25 | .493 |

| Negative Affect | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.8) | 6.21 | .32 | .017 |

| SOCRATESb | ||||||

| Ambivalence/Problem Recognition | 36.4 (5.2) | 39.0 (4.7) | 33.5 (4.3) | 4.73 | 1.22 | .035 |

| Taking Steps | 22.7 (4.8) | 24.1 (4.3) | 21.1 (4.9) | 16.50 | .65 | <.001 |

Note: ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale; AASE = Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale; SOCRATES = Stage of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale. Income was measured using a 1–7 interval scale with 1=$0–10,000 and 8=$70,001 or more.

Chi-square was not performed due to cell size of 1 for minority and rapid changer.

SOCRATES was scored based on a two-factor scale (Maisto et al., 1999): Ambivalence/Problem Recognition (9 items) and Taking Steps (6 items).

Measures

Demographic characteristics, current status information (e.g., marital status, employment) and substance abuse treatment history were obtained using a comprehensive background questionnaire administered during the initial baseline assessment appointment.

Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale (AASE; DiClemente, Carbonari, Montgomery, & Hughes, 1994)

The AASE evaluates self-efficacy to abstain from drinking in 20 situations. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all to 5=extremely) and form four subscales: Negative Affect, Social/Positive, Physical/Other Concerns, and Withdrawal and Urges.

Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner & Allen, 1982)

The ADS is a 25-item scale that measures features of alcohol dependence including the loss of behavioral control (e.g., blackouts), obsessive-compulsive drinking style (e.g., sneaking drinks), and symptoms of withdrawal (e.g., hangovers and hallucinations).

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark & Tellegen, 1988)

The PANAS is a 20-item self-report measure in which participants indicate the extent to which they are currently experiencing the emotion represented by each item on a 5-point scale (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 =extremely).

Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES; Miller & Tonigan, 1996)

The SOCRATES is a 19-item self-report measure designed to assess awareness of problem drinking and motivation to change drinking behavior. Items are rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert scale and form three subscales: problem recognition, ambivalence, and taking steps to make a change.

Timeline Follow-back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992)

The TLFB is a calendar-based retrospective recall interview of daily alcohol use. The TLFB was used to estimate drinks per drinking day and percent days abstinent over the 6-month period prior to the baseline assessment, the 12-week treatment period, and 3-months post treatment.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through radio and newspaper advertisements. Individuals calling the project phone number were screened for initial inclusion criteria (e.g., drank alcohol in past 3 months, not mandated to receive treatment, not currently receiving any other treatment for an alcohol problem) and provided a description of the treatment program. In addition to the eligibility criteria, the 10-minute phone screen included demographic questions (i.e., age, marital and employment status, and race/ethnicity), one question about the frequency of alcohol use and one question about the quantity of alcohol consumed on a typical drinking day. If the initial eligibility criteria were met, participants were scheduled for a baseline interview (~ 90 minutes). During the baseline appointment, informed consent was obtained, alcohol dependence diagnosis was assessed, and the questionnaires described above were completed.

All participants received 12-weeks of standard CBT for alcohol dependence (60-minute sessions). Clinical research assessments were conducted at baseline, end of treatment, and at 3-months post-treatment. Using data from both baseline and end of treatment assessments, pretreatment intervals were created. Three intervals were created using the baseline TLFB: a) Phone call to Baseline, b) Pre-phone (14 days prior to phone call), and c) Past History (everything prior to the pre-phone interval). For each participant, the date of their phone call (when first expressing interest in the study) was mapped onto the 180-day TLFB that was administered at the baseline assessment and drinks per drinking day and percent days abstinent were computed for each interval. The final pretreatment interval, namely baseline to treatment session 1, was created using drinking data collected at the end of treatment assessment by mapping the first treatment session onto the TLFB. The average number of days for the Phone-call to Baseline and Baseline to Treatment Session 1 intervals were 7.0 (SD = 11.7) and 13.2 (SD = 13.2) days, respectively.

Results

Changes in Drinking Prior to the First Treatment Session

To explore changes in drinking prior to the first treatment session, repeated measures ANOVAs (History, Pre-phone, Phone-Baseline, Baseline-Tx1) were conducted. For each analysis corrections were applied when appropriate (e.g., Greenhouse-Geisser). Significant main effects were found for percent days abstinent (PDA), F (3, 132) = 30.63, p < .001, partial η2 = .41, and drinks per drinking day (DDD), F (3, 132) = 16.96, p < .001, partial η2 = .28. Follow-up analyses revealed significant increases in PDA [F (1, 44) = 47.68, p < .001, partial η2 = .52] and decreases in DDD [F (1, 44) = 29.52, p < .001, partial η2 = .40.] between the “pre-phone” and “phone call to baseline” intervals only, suggesting that the majority of change in drinking occurs between the phone call and baseline assessment (see Table 2 for means).

Table 2.

Mean Alcohol Use (SD) During the Pretreatment and Post-Treatment Intervals

| Percent Days Abstinent | Drinks per Drinking Day | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Past History | Pre- phone | Phone to Baseline | Baseline to Tx1 | Post-Tx | 3-Month | Past History | Pre- phone | Phone to Baseline | Baseline to Tx1 | Post-Tx | 3-Month | |

| Overall | 23.8 (28.3) | 30.8 (35.1) | 64.8 (36.5) | 59.2 (37.7) | 77.3 (30.5) | 68.1 (33.5) | 8.5 (4.1) | 8.1 (4.8) | 4.4 5.4) | 4.5 (4.5) | 2.8 (3.4) | 3.6 (3.4) |

| Rapid (n=24) | 27.3 (31.0) | 45.9 (36.9) | 79.3 (30.4) | 89.0 (19.5) | 93.2 (16.8) | 87.3 (20.4) | 8.2 (4.2) | 7.4 (5.4) | 3.5 (5.5) | 1.4 (2.6) | 1.3 (2.1) | 2.2 (3.1) |

| Gradual (n=21) | 20.9 (25.6) | 15.0 (24.7) | 48.2 (36.5) | 25.2 (20.0) | 59.2 (30.5) | 44.7 (31.7) | 8.8 (4.1) | 8.8 (4.1) | 5.4 (5.1) | 8.1 (3.6) | 4.5 (3.8) | 5.3 (3.1) |

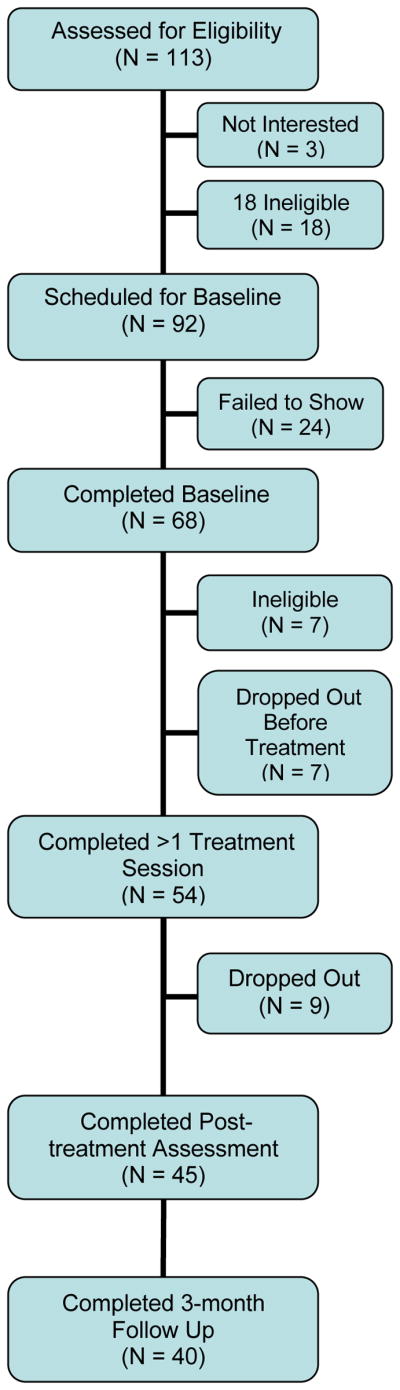

Types of Change during Pretreatment and Impact on Treatment Outcomes

Examination of individual scatter plots suggested two patterns of change: a) rapid change across the pretreatment intervals that was maintained during treatment and b) minimal change across the pretreatment intervals and gradual change during treatment. To examine these patterns further, the individual scatter plots were classified by two independent raters as a rapid or gradual pattern of change and two sets of analyses were conducted.

First, multilevel growth curve models were estimated using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM 7; Raudenbush et al., 2011). Parameters for PDA were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood with robust standard errors, whereas DDD was treated as a count variable and estimated with Poisson estimation with robust standard errors. For each model, linear, quadratic, cubic, and quartic effects were modeled as level 1 predictors, and Change (0 = gradual changer, 1 = rapid changer) was modeled as a level 2 moderator on all level 1 predictors, including the intercept. Due to minimal changes, an averaged past history time point was included in the model. Results indicated no baseline (i.e., past history) differences between gradual and rapid changers on PDA or DDD (see Table 3 for summary). However, significant linear, quadratic, cubic, and quartic effects for PDA and linear, quadratic, and cubic effects for DDDs were observed for rapid changers (i.e., significant interactions). Visual inspection of these effects (Figure 2) revealed greater increases in PDA and decreases in DDD during the pretreatment intervals for the rapid changers which then slowed during treatment and post treatment intervals. In contrast, gradual changers demonstrated slower, yet significant, increases in PDA and decreases in DDD during treatment, with PDA slowing and beginning to decline during post-treatment. Finally, rapid changers had significantly higher PDA (b = 39.02, p <. 001) and lower DDD (b = -1.30, p <. 001) at 90 days post treatment when compared to gradual changers.

Table 3.

Summary of results from MLM growth curve analyses

| Percent Days Abstinent | Drinks per Drinking Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| b | SE | p-value | b | SE | p-value | |

| Intercept | 25.968 | 5.710 | <.001 | 2.180 | .094 | <.001 |

| Intercept X Change | 4.182 | 8.382 | .620 | .063 | .152 | .683 |

| Time | -3.945 | 3.283 | .230 | -.067 | .025 | .008 |

| Time X Change | 29.256 | 4.446 | <.001 | -.551 | .093 | <.001 |

| Time2 | 1.397 | .686 | .042 | .000 | .003 | .972 |

| Time2 X Change | -4.820 | .853 | <.001 | .051 | .011 | <.001 |

| Time3 | -.095 | .046 | .040 | .000 | .000 | .429 |

| Time3 X Change | .282 | .056 | <.001 | -.0013 | .0003 | <.001 |

| Time4 | .002 | .001 | .055 | -- | -- | -- |

| Time4 X Change | -.005 | .001 | <.001 | -- | -- | -- |

Note: Change is a level 2 moderator with 0 = gradual changers and 1 = rapid changers. Runtime level 1 n=990. Percent Days Abstinent was estimated with restricted maximum likelihood with robust standard errors and Drinks per Drinking Day with Poisson estimation with robust standard errors. To reduce the number of intervals and to fit the most parsimonious models, past history intervals were entered as a summary variable due to minimal changes in drinking over the 166 days; therefore, 23 time intervals were included in all final analyses. All time effects were estimated as fixed effects.

Figure 2.

Raw means (dotted lines) and estimated growth curves (solid lines) for gradual vs. rapid changers on percent days abstinent (top panel) and drinks per drinking day (bottom panel).

To examine effect sizes, and to replicate the HLM results, a 2 (Group) X 5 (Interval; 4 pretreatment intervals, 3-month follow-up) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. Significant Group X Interval interactions for PDA [F (3.2, 123.0) = 9.32, p < .001, partial η2 = .20] and DDD [F (3.2, 120.22) = 5.54, p = .001, partial η2 = .13] were found. Follow-up contrasts revealed that rapid changers had greater increases in PDA [F (1, 38) = 40.81, p < .001, partial η2 = .52] and decreases in DDD [F (1, 38) = 19.87, p < .001, partial η2 = .34] during pretreatment (i.e., Past History to Treatment Session 1) when compared to gradual changers. In contrast, gradual changers demonstrated a significantly greater increase in PDA [F (1, 38) = 10.32, p = .003, partial η2 = .21] and decrease in DDD [F (1, 38) = 8.28, p = .007, partial η2 = .18] between treatment session 1 and the 3-month follow-up when compared to rapid changers, suggesting that the majority of change for rapid changers occurs prior to receiving any formal treatment. Finally, compared to gradual changers, rapid changers had higher PDA [F (1, 38) = 26.24, p < .001, partial η2 = .41] and lower DDD [F (1, 38) = 9.92, p = .003, partial η2 = .21] at 3-months.

No differences between rapid and gradual changers were noted on baseline assessments of severity of alcohol dependence, self-efficacy, positive affect, employment status, earned income, age, years of education, number of treatment sessions attended, previous outpatient treatment attempts, or gender composition. Rapid changers, however, did score significantly higher on baseline negative affect, and measures of ambivalence/problem recognition and taking steps to make a change (see Table 1 for summary of results).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that, for some individuals, a significant amount of alcohol behavior change occurs after seeking treatment and before treatment begins. These changes were also maintained over the course of treatment with the rapid change group having significantly better treatment outcomes compared to the gradual change group. These results are consistent with a small number of studies in the alcohol treatment field, as well as research investigating rapid early response in the treatment of anxiety and depression (e.g., Aderka et al., 2012; Tang & DeRubeis, 1999), and have several methodological and clinical implications.

Methodologically, changes occurring before treatment, if not accounted for, may result in the misattribution of positive outcomes to the experimental treatment rather than to the pre-treatment change process (Epstein et al., 2005). In the present study, following substantial changes in percent days abstinent (PDA) and drinks per drinking day (DDD), the rapid change group did not show further significant within-treatment drinking change. Thus, the data challenge the assumption that the major portion of the change process occurs after treatment entry. The analyses of treatment effects commonly compare measures of alcohol use obtained at baseline, which typically occurs one or more weeks prior to the first treatment session, with values obtained at post-treatment. This approach leads to higher baseline values as it typically includes a 3- or 6-month period of heavier drinking and does not adequately account for changes in drinking made during the pretreatment window. The result is that pretreatment changes in drinking are being attributed to the effects of treatment rather than a more self-guided or naturally occurring pretreatment change process. Repositioning the starting values for treatment outcome analyses to exclude pretreatment changes in drinking would provide a clearer indication of alcohol treatment response and treatment effects.

In the present study, two independent raters examined scatter plots of daily drinking profiles and identified individuals as either rapid or gradual changers. While classification as a rapid changer was aided by the large number of individuals in this group who had achieved abstinence prior to attending the first treatment session (70.8%), this method of case identification potentially limits our precision to detect more subtle variations in pretreatment drinking trajectories. Therefore, to better capture the change process, statistical analyses such as Group Based Trajectory Modeling (GBTM; Nagin, 1999) or Growth Mixture Modeling (GMM; Muthen & Muthen, 2000) could be used to identify different trajectories of pre-treatment change. The different trajectory classes identified could then be used to predict change within treatment and treatment outcomes. Such an approach, not used in the current study due to sample size limitations, would also allow researchers to compare the rates of progress over the pretreatment period versus during the course of treatment. Importantly, an increased focus would be placed on examining the ability of interventions to stabilize and maintain a pre-existing change process.

Clinically, identifying subgroups of individuals based on their trajectory of pretreatment change has the potential to inform clinical decision making. The results of this study suggest that one role of treatment may be to help rapid changers stabilize and maintain pretreatment changes. If so, then formal treatment could be adapted to capitalize on changes already made. For example, an initial treatment session that provides feedback to the individual that s/he is already doing something that makes a desired difference in the problem could serve to reinforce a positive self-efficacy expectation (Bandura, 1977). Individuals who receive such feedback may see themselves as more capable and have greater confidence in their ability to maintain these changes or facilitate further changes. Moreover, a brief intervention has the potential to be more efficient for those individuals who have made substantial pretreatment changes. A course of relapse prevention might also have utility. Alternatively, for the gradual change group, adaptations to the initial or early treatment period might include more frequent sessions (e.g., twice weekly for the first month) in an effort to increase abstinence days and reinforce self-efficacy for change. The goal for the gradual change group would be to alter the trajectory of change during this early treatment period. So-called “adaptive research designs” have recently received support in the treatment of cocaine dependence (Petry et al., 2012) such that cocaine-dependent individuals entering treatment with a cocaine-positive drug test received higher magnitude abstinence-based reinforcement (contingency management; CM) and had equivalent outcomes to those who had a cocaine-negative drug test and received standard CM.

A potential limitation of this study is that participants’ reports of drinking for the baseline to treatment session 1 interval were based on data collected during the end of treatment administration of the Timeline Follow-back assessment. Because people are prone to assume a high degree of stability in their behavior, it is possible that individuals with better treatment outcomes provided retrospective reports of their drinking that were more similar to their present behavior (Schwartz, 2012). Unfortunately, unlike Epstein et al. (2005), we did not assess drinking behavior for this interval at the first treatment session. Partially mitigating this potential retrospective report bias is our finding that the majority of change in drinking occurs between the phone call and baseline assessment, the pretreatment interval most proximal to the baseline administration of the TLFB. Also, the validity of the TFLB has been demonstrated in studies covering assessment durations equivalent to those reported here (e.g., Toll, Cooney, McKee, & O’Malley, 2006). Nevertheless, future studies could be designed to assess daily drinking during the pretreatment period using weekly retrospective reports or newer assessment technologies such as Interactive Voice Response (IVR). While not a limitation of the current study per se, assessment reactivity has been offered as a possible explanation for pretreatment drinking changes (Epstein et al., 2005). However, assessment reactivity cannot explain all pretreatment change, as our results show change occurring after the initial phone contact and before the baseline assessment. Thus, similar to Sobell (2011), who showed change occurring between 2 and 4 weeks before the phone call, it appears for some that behavior change is a process that begins in the weeks and months leading up to treatment (Orford, 2006b; Willenbring, 2007).

A focus of treatment process research has been to examine potential precursors to change and/or mediators of change. Changes in drinking, however, may lead to subsequent cognitive and affective changes, which themselves lead to further reduction in drinking. For example, in the literature examining sudden gains for those with depression, it’s been observed that sudden gains may spark a positive feedback loop referred to as an “upward spiral” (Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). Future studies investigating pretreatment changes in drinking should focus on the cognitive and affective processes occurring after substantial pretreatment changes as they may play a role in facilitating and maintaining the long-term effects of pretreatment changes. With regard to the possible role of CBT in maintaining the pretreatment changes observed, future studies could focus on non-CBT interventions in order to increase our understanding of pretreatment change and how such changes are maintained across diverse treatments.

In summary, the data from this study suggest that a more systematic investigation of pretreatment changes in alcohol use is warranted. A more detailed investigation may yield insights that could lead to more efficient treatment delivery and suggest avenues for adapting treatment based on a person’s pretreatment change status.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants RC1 AA018986 and T32 AA007583.

Contributor Information

Paul R. Stasiewicz, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Robert C. Schlauch, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Clara M. Bradizza, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Christopher W. Bole, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Scott F. Coffey, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, The University of Mississippi Medical Center

References

- Aderka IM, Nickerson A, Boe HJ, Hofman SG. Sudden gains during psychological treatments of anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:93–101. doi: 10.1037/a0026455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP, Montgomery RPG, Hughes SO. The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:141–148. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, Drapkin ML, Yusko DA, Cook SM, McCrady BS, Jensen NK. Is alcohol assessment therapeutic? Pretreatment change in drinking among alcohol dependent women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:369–378. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Burke RH. Can assessment reactivity predict treatment outcome among adolescents with alcohol and other substance use disorders? Substance Abuse. 2008;29:63–69. doi: 10.1080/08897070802093262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindsvatter A, Osborn CJ, Bubenzer D, Duba JD. Client perceptions of pretreatment change. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2010;88:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson D. Identifying pretreatment change. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1994;72:244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, NcNeil M, Kraemer K, O’Connor M, Kelly ME. Factor structure of the SOCRATES in a sample of primary care patients. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:879–892. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Irwin TW, Wainberg ML, Parsons JT, Muench F, Bux DA, Kahler CW, Marcus S, Schulz-Heik J. A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:72–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. Analyzing developmental trajectories: Semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness ME, Murphy JJ. Pretreatment change reports by clients in a University counseling center: Relationship to inquiry technique, client, and situational variables. Journal of College Counseling. 2001;4:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Hodgson R, Copella A, et al. The clients’ perspective on change during treatment for an alcohol problem: qualitative analysis of follow-up interviews in the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial. Addiction. 2006a;101:60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Kerr C, Copello A, et al. Why people enter treatment for alcohol problems: Findings from UK alcohol treatment trial pre-treatment interviews. Journal of Substance Use. 2006b;11:161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Penberthy JK, Ait-Daoud N, Breton M, Kovatchev B, DiClemente CC, Johnson BA. Evaluating readiness and treatment seeking effects in a pharmacotherapy trial fro alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1538–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Barry D, Alessi SM, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. A randomized trial adapting contingency management targets based on initial abstinence status of cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:276–285. doi: 10.1037/a0026883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon RT, du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Scientific Software International, Inc; Lincolnwood, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Why researchers should think “real-time”: A cognitive rationale. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janvas J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1982;91:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. Self-change: Findings and implications for the treatment of addictive behaviors. Presented at the 8th Annual INEBRIA Conference; Boston, MA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, Sobell MB. Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: prevalence in two population surveys. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:966–972. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumptin: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. p. 41072. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Toneatto T. Recovery from alcohol problems without treatment. In: Heather N, Miller WR, Greeley J, editors. Self-control and Addictive Behaviors. New South Wales. Australia: Maxwell MacMillan; 1991. pp. 198–242. [Google Scholar]

- Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ. Reconsidering rapid early response in cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:283–288. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Cooney NL, McKee SA, O’Malley SS. Correspondence between interactive voice response (IVR) and Timeline Followback (TLFB) reports of drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner-Davis M, de Shazer S, Gingerich WJ. Building on pretreatment change to construct the therapeutic solution: An exploratory study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1987;13:359–363. [Google Scholar]

- West DS, Harvey-Berino J, Krukowksi RA, Skelly JM. Pretreatment weight change is associated with obesity treatment outcomes. Obesity. 2011;19:1791–1795. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring ML. A broader view of change in drinking behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:84S–86S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]