Abstract

ObjectiveTo investigate disparities in mental health care episodes, aligning our analyses with decisions to start or drop treatment, and choices made during treatment.

Study DesignWe analyzed whites, blacks, and Latinos with probable mental illness from Panels 9–13 of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, assessing disparities at the beginning, middle, and end of episodes of care (initiation, adequate care, having an episode with only psychotropic drug fills, intensity of care, the mixture of primary care provider (PCP) and specialist visits, use of acute psychiatric care, and termination).

FindingsCompared with whites, blacks and Latinos had less initiation and adequacy of care. Black and Latino episodes were shorter and had fewer psychotropic drug fills. Black episodes had a greater proportion of specialist visits and Latino episodes had a greater proportion of PCP visits. Blacks were more likely to have an episode with acute psychiatric care.

ConclusionsDisparities in adequate care were driven by initiation disparities, reinforcing the need for policies that improve access. Many episodes were characterized only by psychotropic drug fills, suggesting inadequate medication guidance. Blacks’ higher rate of specialist use contradicts previous studies and deserves future investigation. Blacks’ greater acute mental health care use raises concerns over monitoring of their treatment.

Keywords: Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care, episodes of care, longitudinal data, panel data, psychotropic drug use

Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care remain large (AHRQ 2009) and persistent (Blanco et al. 2007; Cook, McGuire, and Miranda 2007; Ault-Brutus 2012). Blacks and Latinos access mental health care at half the rate of non-Latino whites (Wells et al. 2001; AHRQ 2008), even after accounting for mental health status (Cook, McGuire, and Miranda 2007), with higher rates of attrition following initiation of care (Hodgkin, Volpe-Vartanian, and Alegría 2007). These disparities may be partly attributable to lower engagement in the general medical health care system where mental illness is recognized and referrals to specialty mental health care occur. Blacks and Latinos are less likely than whites to have a regular primary care provider (PCP), a usual source of care, and a past year health care visit, and more likely to report emergency room (ER) use (Collins, Hall, and Neuhaus 1999; Kaiser Family Foundation 2003). These service use disparities likely contribute to the greater persistence, severity, and disease burden of mental disorders among racial/ethnic minorities (Breslau et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2007).

Defining Disparities in Mental Health Care

We follow prior literature (e.g., McGuire et al. 2006; Duan et al. 2008; Cook, McGuire, and Zaslavsky 2012; Mahmoudi and Jensen 2012) in defining a mental health care disparity in accordance with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Unequal Treatment report. The report regards health care disparities as all racial/ethnic differences in health care quality except those that are due to clinical appropriateness and need and patient preferences (IOM 2002)1. In using this definition, we exclude from the disparity calculation differences based, for example, on health status but include differences related to the operation of health care systems, the legal and regulatory climate, and provider discrimination. Estimates of “disparities” are adjusted for clinical appropriateness and need, but not for socioeconomic status (SES) and other non-need variables (McGuire et al. 2006; Cook, McGuire, and Zaslavsky 2012). A comparison of results derived from IOM-concordant methods and other disparity methods show that estimates and policy implications can vary significantly depending on the method used (Cook et al. 2009b; Cook, McGuire, and Zaslavsky 2012).

Episodes of Care as a Means to Characterize Disparities

Disparities in mental health treatment are usually calculated based on average annual spending per person (Ringel and Sturm 2001; Zuvekas 2005) or by the likelihood of any use within the last year (Wells et al. 2001; Alegria et al. 2008; Stockdale et al. 2008). Such cross-sectional analyses may mask important information relevant to understanding disparities and identifying policies to decrease them. For example, comparisons of service use over a 12-month period cannot distinguish between higher rates of initiation and longer episodes of treatment.

An alternative, describing “episodes” of mental health care, includes evaluating initial evaluations in a PCP or specialist setting, follow-up visits with monitoring of medication use, acute psychiatric treatment, and treatment maintenance until recovery or termination of care. Defining mental health care use in terms of episodes was the basis of early work in the economics of mental health and has the advantage of isolating disparate factors (such as the decision to seek treatment and adequacy of treatment), which characterize demand for care (Ellis and McGuire 1984; Keeler, Manning, and Wells 1988; Haas-Wilson, Cheadle, and Scheffler 1989). Prior episode studies have identified a high frequency of churning in and out of mental health care (McFarland and Klein 2005), estimated demand for mental health services by type of treatment episode (outpatient, drug treatment, hospitalization) (Haas-Wilson, Cheadle, and Scheffler 1989; Meyerhoefer and Zuvekas 2010), assessed the effect of previous psychiatric care on long-term psychiatric care costs (Mirandola et al. 2004), and analyzed depression treatment patterns (Busch, Leslie, and Rosenheck 2004).

Patterns of Care among Racial/Ethnic Minorities

Racial/ethnic disparities in initiation of treatment are likely given numerous cross-sectional studies identifying disparities in any access to mental health care (Blanco et al. 2007; Cook et al. 2010). Prior studies also document disparities in quality of care (Harman, Edlund, and Fortney 2004; Simpson et al. 2007). Quality disparities may in part be driven by minorities’ greater likelihood of seeking mental health care services in general medical settings (Cooper et al. 2003b; Miranda and Cooper 2004) where individuals receiving mental health care reported fewer visits than those in the specialty mental health sector (1.7–7.4 visits, respectively) (Wang, Demier, and Kessler 2002). Racial/ethnic minorities may also have shorter duration of care because they are more likely to drop out (Sue, Zane, and Young 1994) and have lower satisfaction with their care (Jackson et al. 2007). A countervailing factor that may actually lengthen racial/ethnic minority episodes in comparison to whites is that minorities initiate care later, at more severe stages of mental illness because of differing preferences and attitudes toward care (Cooper-Patrick et al. 1997; Cooper et al. 2003b), and physician under-diagnosis of mental illness among minority patients (Borowsky et al. 2000). Longer treatment episodes may be necessary to treat the more severe racial/ethnic minority patients that do enter treatment.

In this study, we apply the IOM definition to the measurement of disparities in episodes of mental health care. This approach seeks to estimate disparities that are attributable to the health care system, and it targets the critical decision points in use of mental health care.

Methods

Data

We assessed disparities in patterns of mental health care episodes for adults (ages 18+) with probable need for mental health or substance abuse treatment services from panels 9–13 of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Data collection for each panel were conducted across five survey rounds across a 2-year period (Panel 9 corresponds to years 2004–2005, Panel 10, 2005–2006… Panel 13, 2008–2009). We considered a respondent to have probable need if he or she scored greater than 2 on the PHQ-2 depression symptom checklist (indicating probable depressive disorder) or greater than 12 on the K6 survey (indicating nonspecific psychological distress) (Kessler et al. 2003). The PHQ-2 is a sensitive (93 percent) and specific (75 percent) indicator for any depressive disorder (Kroenke, Spitzer, and Williams 2003). The K6 scale is predictive of severe mental illness defined as any individual with a DSM-IV diagnosis and severe impairment (Kessler et al. 2003). Panels 9–13 include 47,903 white, black, and Latino adults age 18+. Of these, 5,161 individuals (2,594 non-Latino whites, 1,134 blacks, and 1,433 Latinos) fulfilled our criteria for probable mental illness and were included in our sample. Native Americans and Asian Americans were excluded because of small sample sizes.

To address missing data in the MEPS (3 percent missing on priority chronic health conditions and less than 1 percent on other variables), we implemented multiple imputation methods using the mi procedure in Stata (StataCorp 2011). This technique creates five complete datasets, imputing missing values using a chained equations approach, analyzes each dataset, and uses standard rules to combine the estimates and adjust standard errors for the uncertainty due to imputation (Rubin 1998; Little and Rubin 2002).

Definition of an Episode of Mental Health Care

Episodes of mental health care are constructed based on respondents’ reported diagnosis and timing of each treatment event. Mental health events include (1) treatment provided by a mental health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, counselor, or social worker) or PCP for a disorder covered by ICD-9 codes 291, 292, or 295–314 (Zuvekas 2001); (2) prescribed medicine purchases (or “fills”) linked with one of these ICD-9 codes; or (3) fills of prescribed medicine considered to be a psychotropic drug according to the Multum Lexicon Drug Database (Multum Information Services, 2009). This methodology is shown to have strong sensitivity (88 percent) to provider reports of treatment of behavioral health disorders (Machlin et al. 2009). An episode begins with a mental health care event following a period of at least 12 weeks without treatment, and it ends when care stops for 12 weeks or longer. Gaps of 84–90 days have been used to define episodes in prior research (Keeler, Manning, and Wells 1988; Tansella et al. 1995; Farmer Teh et al. 2010) and were found to be both clinically appropriate and the most acceptable break point in a comparison of different thresholds of treatment gaps (Tansella et al. 1995).

Because the MEPS does not collect dates of drug fills except for the first fill, we imputed drug fill dates similar to Selden (2009). This imputation method uses the start date of the initial fill, the start and end date of the survey round (the MEPS is administered in five rounds, approximately 5 months apart), and the number of fills per round (i.e., if one fill, we impute the day in the middle of the round; for two fills, we impute two dates one-third and two-thirds of the way through the round, etc.).

Primary Outcome Variables

Our outcome variables characterize the mental health care episode. We first measured initiation of care. In the follow-up phase, we measured quality of care (minimally adequate care and the probability of having an episode with only psychotropic drug fills among those that initiated), utilization of care among those that initiated care (visits, days, and expenditures, and proportion of events that were specialist visits, PCP visits, and psychotropic drug fill events), and utilization of acute psychiatric care (having a psychiatric ER visit or psychiatric inpatient [IP] stay). We consider both psychiatric ER and IP visits to be negative quality indicators for patients, assuming that they represent an interruption to the continuity of outpatient mental health care and can be reduced with proper outpatient and pharmaceutical drug treatment episodes. To assess termination, we assessed whether care stopped for 12 weeks or longer before minimally adequate treatment was achieved.

Expenditure measures were constructed by summing all direct payments for mental health care provided, including out-of-pocket payments and payments by private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, and other sources.

Minimally adequate care was defined as four or more mental health care visits or events with at least one psychotropic medication fill, or eight or more visits for mental illness to a psychiatrist or other mental health care provider. For those with schizophrenia disorder diagnosis (ICD-9 code of 295), only the former criterion was applied (Wang, Demier, and Kessler 2002). This definition draws on evidence-based practice treatment guidelines for depressive and anxiety disorders and other severe mental illnesses to define minimum thresholds for guideline-concordant treatment has been used elsewhere (Wang, Berglund, and Kessler 2000; Wang, Demier, and Kessler 2002; Wang et al. 2005; Alegria et al. 2008) and is consistent with recommendations for treatment type and duration from the American Psychiatric Association (APA 2010).

Primary Independent Variables

Racial/ethnic categories are based on U.S. Census definitions. In accordance with the IOM definition of health care disparities (IOM 2002; McGuire et al. 2006), we classified covariates other than race/ethnicity as “need” or “non-need.” Variables indicating need were adjusted in disparity calculations and include self-reported mental and physical health, the mental and physical health components of the SF-12, the PHQ-2 scale for depression, the K-6 scale of psychological distress, as well as gender and age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75+). Physical health variables were also considered as indicating need given the high rates of comorbidity between physical ailments and mental disorders (Alexopoulos et al. 1997; Afari et al. 2001; de Groot et al. 2001; Clarke and Meiris 2007) and include any limitation due to physical health, body mass index, and a list of 11 chronic health illnesses.

Non-need variables were not adjusted for in disparity estimates. These are income (less than the federal poverty level [FPL], 100–125 percent FPL, 125–200 percent FPL, 200–400 percent FPL, 400 percent FPL+), education (less than high school [HS], HS graduate, any college, college graduate), health insurance (private insurance, public insurance, uninsured), participation in an HMO, region of the country (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), employment status (employed or not), residence in a metropolitan statistical area, and marital status (married or not).

The IOM definition also calls for adjustment of patient preferences when estimating disparities. However, accounting for preferences presents a challenge because patients are rarely “fully informed” about their clinical options when deciding to access health care (IOM 2002; Ashton et al. 2003), preferences may themselves have been influenced by contributors to disparities, such as past discrimination (Cooper-Patrick et al. 1997), and may be endogenous to treatment.

Statistical Analysis

We describe our sample by presenting unadjusted rates of episode characteristics, need, and non-need variables. To estimate disparities, we follow a four-step process: (1) estimate a fully specified regression model appropriate to the dependent variable of interest conditional on both need and non-need variables; (2) transform only need distributions to be equal across racial/ethnic groups; (3) predict mental health care based on the original model coefficients, original race and SES characteristics, and the transformed need characteristics; and (4) compare mean white estimates with minority estimates with transformed need characteristics.

Model Estimation

All estimation models follow a similar basic structure:

| (1) |

where Yi is the measure of mental health care use, f is the functional form that best fits the data, and Racei, Needij, and Non-Needij represent groups of vectors of covariates as described in the data section for episode j within individual i. We estimated logistic regression models, accounting for clustering of episodes within the individual, to estimate initiation of mental health care, minimally adequate care, having a psychotropic drug only episode, any ER/IP use, and termination of care.

In our analyses of continuous variables conditional upon probable mental illness and any mental health care, we accounted for left-and right-censoring of number of visits and length of episode using censored normal regression. This estimation method is equivalent to standard survival analysis techniques using a normal distribution for the response variable. We estimated the same model for episode expenditures except we first applied the log transformation to the expenditures before applying the censored normal regression.

Adjustment for Health Status to Achieve Concordance with IOM Definition

Next, we transformed the distributions of mental health and health status (need variables) of minority populations to be equivalent to nonminority white distributions using the rank-and-replace adjustment method described in detail elsewhere (Cook et al. 2009b). Multivariate indicators of need are summarized with a univariate summary index of need (Cook, McGuire, and Miranda 2007; Cook et al. 2010) defined as the sum of the terms (coefficient times covariate) of the fitted model corresponding to need variables. Survey-weighted ranks were then assigned to each individual within each racial/ethnic group based on the summary index of need. The need index values of each minority individual were then replaced with those of the equivalently ranked white individual. This adjustment method creates a counterfactual population of black or Latino individuals with the white distribution of mental health care need.

In step 3, we calculated predicted use and expenditure for each minority individual using the coefficients from the original regression model and the adjusted need covariate values. In step 4, the mean of these minority group predictions is subtracted from the mean of whites’ predictions.

Variance estimates for predicted expenditure rates and amounts for disparity comparisons were calculated using a balanced-repeated-replication (BRR) procedure (Wolter 1985). The BRR accounts for the stratified design of the MEPS survey and the clustering of observations at the individual and family level (AHRQ 2012b). Stratum and primary sampling unit variables were standardized across pooled years (AHRQ 2012a).

Sensitivity Analyses

We tested the sensitivity of all estimates to alternative model specifications and to alternative procedures that account for left-and right-censoring. For dichotomous response variables, we compared our main results with (1) a logit model excluding right censored observations and (2) a logit model treating the response variable for censored episodes as 0. For continuous response variables, we compared our main results with regression model results, which (1) ignored the issue of censoring by treating censored observations as fully observed and (2) dropped censored episodes from the sample. We also considered models for the response variable that were Poisson or Gamma generalized linear models.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Blacks and Latinos were significantly less likely than whites to initiate care, have an adequate episode of care, or to have an episode with psychotropic drug use only. Blacks were significantly more likely to have an episode of care with a psychiatric ER or IP visit and Latinos had episodes with significantly fewer days. There were no differences in the number of mental health care episodes with about half of the respondents reporting greater than one mental health care episode (Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted, Unadjusted Characteristics of Sample of Individuals with Probable Mental Disorder (n = 6,832 episodes/5,161 individuals)

| Outcome Variables | White | Black | Sig. | p-Value | Latino | Sig. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial phase of care | |||||||

| Initiation of care | 39.8% | 21.9% | *** | <.001 | 24.6% | *** | <.001 |

| Follow-up | |||||||

| Adequacy of care | 16.0% | 8.8% | *** | <.001 | 9.2% | *** | <.001 |

| RX only | 49.4% | 35.9% | *** | <.001 | 36.2% | *** | <.001 |

| Length of episode (days) | 183.1 | 166.5 | .219 | 157.7 | * | 0.034 | |

| Number of visits per episode | 5.4 | 5.4 | .904 | 5.5 | 0.904 | ||

| Expenditures per episode ($) | 1,667.3 | 2,103.0 | .213 | 1,761.5 | 0.633 | ||

| ER/IP use within episode | 3.4% | 7.0% | ** | .002 | 3.0% | 0.691 | |

| Termination | |||||||

| Termination before adequate treatment | 77.5% | 75.7% | .480 | 77.7% | 0.935 | ||

| Need-related variables | |||||||

| Mental health status variables | |||||||

| Mental health component SF-12 | 32.1 | 35.7 | *** | <.001 | 35.0 | *** | <.001 |

| Severe psychological distress (K-6 ≥13) | 12.8 | 12.1 | ** | .001 | 13.3 | * | 0.034 |

| Probable depressive disorder (PHQ-2 >2) | 4.0 | 3.9 | * | .024 | 4.0 | 0.792 | |

| Self-rated mental health | |||||||

| Excellent | 8.7% | 15.9% | *** | <.001 | 14.8% | *** | <.001 |

| Very good | 15.9% | 19.1% | .082 | 19.5% | * | 0.043 | |

| Good | 32.4% | 29.5% | .173 | 34.2% | 0.425 | ||

| Fair | 30.9% | 25.9% | * | .021 | 24.1% | ** | 0.002 |

| Poor | 12.2% | 9.6% | .152 | 7.5% | ** | 0.002 | |

| Other health status variables | |||||||

| 0 Physical health comorbidities | 30.7% | 33.2% | .293 | 46.6% | *** | <.001 | |

| 1 Physical health comorbidty | 22.6% | 22.9% | .886 | 19.4% | 0.090 | ||

| 2+ Physical health comorbidities | 46.7% | 43.9% | .262 | 34.0% | *** | <.001 | |

| Physical health component SF-12 | 41.2 | 40.8 | .574 | 42.4 | 0.055 | ||

| Any work limitation | 35.4% | 33.6% | .434 | 25.4% | *** | <.001 | |

| Other covariates related to need | |||||||

| Female | 60.9% | 65.2% | * | .040 | 62.7% | 0.375 | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–24 | 8.2% | 12.2% | ** | .009 | 11.2% | * | 0.022 |

| 25–34 | 12.5% | 17.7% | ** | .004 | 20.6% | *** | 0.000 |

| 35–44 | 18.1% | 21.3% | .079 | 17.2% | 0.573 | ||

| 45–54 | 23.1% | 22.5% | .792 | 23.3% | 0.912 | ||

| 55–64 | 19.5% | 15.1% | * | .020 | 15.3% | * | 0.032 |

| 65–74 | 8.8% | 5.8% | * | .018 | 7.9% | 0.519 | |

| 75+ | 9.8% | 5.4% | *** | .000 | 4.6% | *** | 0.000 |

| Married | 47.9% | 25.8% | *** | .000 | 44.1% | 0.113 | |

| Number of episodes observed | |||||||

| 1 Episode | 49.9% | 51.3% | .678 | 54.0% | 0.219 | ||

| 2 Episodes | 32.1% | 31.7% | .899 | 27.9% | 0.131 | ||

| >2 Episodes | 18.0% | 17.0% | .700 | 18.1% | 0.959 | ||

| Non-need variables | |||||||

| % federal poverty level | |||||||

| <100% | 19.8% | 40.6% | *** | <.001 | 32.3% | *** | <.001 |

| 100–124% | 5.6% | 7.9% | * | .028 | 9.1% | *** | <.001 |

| 125–199% | 17.1% | 21.3% | * | .042 | 19.0% | 0.300 | |

| 200–399% | 31.7% | 21.5% | *** | <.001 | 28.6% | 0.186 | |

| 400%+ | 25.9% | 8.7% | *** | <.001 | 11.1% | *** | 0.000 |

| Education | |||||||

| <HS | 22.0% | 36.2% | *** | <.001 | 48.7% | *** | <.001 |

| HS grad | 38.3% | 39.3% | .675 | 27.8% | *** | <.001 | |

| Some college | 23.8% | 17.7% | ** | .002 | 16.0% | *** | <.001 |

| College grad | 15.9% | 6.9% | *** | <.001 | 7.6% | *** | <.001 |

| Health insurance | |||||||

| Any uninsured | 17.1% | 23.4% | *** | <.001 | 30.7% | *** | <.001 |

| Any public notuninsured | 29.5% | 43.1% | *** | <.001 | 37.7% | *** | <.001 |

| Any private not public not uninsured | 53.4% | 33.5% | *** | <.001 | 31.6% | *** | <.001 |

| HMO | 26.8% | 33.7% | ** | .005 | 35.1% | ** | 0.001 |

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 15.8% | 13.8% | .385 | 19.2% | 0.165 | ||

| Midwest | 26.5% | 18.4% | ** | .001 | 6.0% | *** | <.001 |

| South | 36.9% | 58.4% | *** | <.001 | 34.1% | 0.386 | |

| West | 20.8% | 9.5% | *** | <.001 | 40.7% | *** | <.001 |

| Employed | 45.4% | 41.2% | .095 | 43.5% | 0.410 | ||

| Urbanicity | 75.9% | 85.6% | ** | .002 | 94.1% | *** | <.001 |

Subsample of Adult Respondents in Panels 9–13 (2004–2009) of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey with K-6 >12 or PHQ->2.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Compared with whites, blacks and Latinos had greater (healthier) responses to the mental health component of the SF-12 and self-reported mental health (Table 1). Blacks scored lower on the K-6 psychological distress scale and the PHQ-2 depression scale and Latinos scored higher on the K-6 than whites. Latinos were less likely to have multiple physical health comorbidities and to report a work limitation than whites. Demographically, blacks were significantly more likely to be female and less likely to be married, and blacks and Latinos were younger than whites. Blacks and Latinos generally reported having lower income, lower education, greater rates of public insurance and uninsurance, and a higher likelihood of being enrolled in an HMO and living in an urban area than whites. Blacks were more likely to live in the South and Latinos were more likely to live in the West than whites.

Disparity Prediction Estimates

We identified black-white and Latino-white disparities in treatment initiation for those with a probable need for mental health care (40 percent of whites, 24 percent of blacks, and 27 percent of Latinos) (Table 2). During the follow-up phase of treatment, we identified disparities in adequacy of mental health care (16 percent of whites, 10 percent of blacks, and 11 percent of Latinos). Among the subpopulation of individuals that initiated mental health care, whites were significantly more likely than blacks and Latinos to have episodes that only included psychotropic drug fills and there were racial/ethnic disparities in number of days of episodes of mental health treatment (257, 230, and 228 days for whites, blacks, and Latinos, respectively).

Table 2.

IOM-Concordant Racial/Ethnic Disparity Predictions across Episodes of Mental Health Care (n = 6,832 episodes/5,161 individuals)

| Full Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation of Care | |||

| Initial Phase of Care | Estimate | SE | |

| White | 39.8% | 1.1% | |

| Black | 23.7% | 1.4% | |

| B–W disparity | 16.1% | 1.7% | |

| Latino | 27.4% | 1.4% | |

| L–W disparity | 12.3% | 1.8% | |

| Follow-up | Full Sample | ||

| Adequacy of Care | |||

| Estimate | SE | ||

| White | 16.0% | 0.8% | |

| Black | 9.8% | 1.0% | |

| B–W disparity | 6.2% | 1.4% | |

| Latino | 10.7% | 1.1% | |

| L–W disparity | 5.3% | 1.3% | |

| Among Individuals with MH Care | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RX Only | Length (Days) of Episode | |||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |||

| White | 49.4% | 1.3% | 257.34 | 8.79 | ||

| Black | 39.3% | 2.4% | 229.84 | 14.84 | ||

| B–W disparity | 10.1% | 2.6% | 27.50 | 15.75 | ||

| Latino | 37.2% | 2.2% | 228.30 | 14.02 | ||

| L–W disparity | 12.2% | 2.5% | 29.04 | 15.92 | ||

| Number of Visits per Episode | Expenditures per Episode | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |||

| White | 10.86 | 0.93 | 1,368.34 | 161.80 | ||

| Black | 9.98 | 1.17 | 1,193.17 | 207.50 | ||

| B–W disparity | 0.87 | 1.26 | 175.17 | 211.85 | ||

| Latino | 10.47 | 1.09 | 1,296.80 | 212.94 | ||

| L–W disparity | 0.38 | 1.16 | 71.54 | 209.20 | ||

| ER/IP Use within Episode | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | ||

| White | 3.4% | 0.4% | |

| Black | 5.4% | 1.0% | |

| B–W disparity | −2.0% | 1.1% | |

| Latino | 3.2% | 0.8% | |

| L–W disparity | 0.2% | 0.9% | |

| Termination before Adequate Tx | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Termination | Estimate | SE | |

| White | 77.5% | 1.1% | |

| Black | 79.0% | 2.0% | |

| B–W disparity | −1.5% | 2.2% | |

| Latino | 78.7% | 1.9% | |

| L–W disparity | −0.7% | 2.1% | |

Note. Panels 9–13 (2004–2009) Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Bold numbers indicate significant disparities at the p < .05 level.

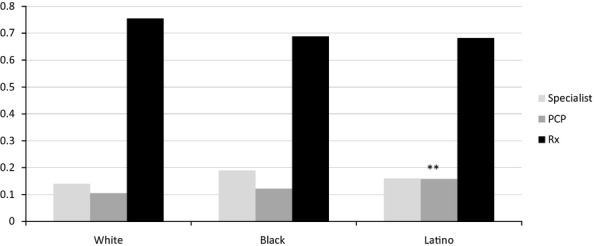

Black and Latino episodes had a smaller proportion of psychotropic drug fill events than white episodes, and black episodes had a greater proportion of specialist visits and Latino episodes had a greater proportion of PCP visits (Figure 1). When excluding psychotropic drug fills, differences in use by treatment modality were similar (black episodes included a greater proportion of specialist visits and Latino episodes included a greater proportion of PCP visits than white episodes; results not shown). Blacks were more likely than whites to have an episode that included a psychiatric ER or IP visit (5.4 percent vs. 3.4 percent, respectively). No statistically significant racial/ethnic differences were identified in the termination of episodes before minimally adequate treatment was achieved (Table 2). We found no differences in the significance or direction of results in sensitivity analyses that test different methods of right-censoring for dichotomous and left-and right-censoring for continuous variables (see Tables S2a–f).

Figure 1.

Proportion of Events during Mental Health Care Episodes Attributable to Specialist Outpatient Visits, PCP Outpatient Visits, and Prescription Drug Fills by Race/Ethnicity (n = 3,359 episodes of 1,688 individuals with initiation of mental health care)

Predictors of Patterns of Mental Health Care

Poorer mental health and greater education were predictive of greater initiation and adequacy of mental health care (see Table S1a). Having multiple comorbidities was positively correlated with the initiation of mental health care and reporting any limitation at work and younger age was positively correlated with receiving minimally adequate care. A number of SES variables were significant predictors of initiation of care and minimally adequate care (i.e., greater income, education, and having public insurance). Negative predictors of adequate care were being uninsured, being fully employed, and living in the South, Midwest, or West (compared with the Northeast).

Predictors of having an episode of mental health care solely comprised of psychotropic drug fills were generally associated in the opposite direction to predictors of adequate care, with poorer mental health, and being fully employed positively correlated (Table S1a). Poorer mental health and physical health were associated with greater utilization of care and expenditures in the utilization models (Table S1b). Greater socioeconomic status was generally positively associated with greater utilization and expenditures, whereas lack of insurance and being fully employed were negative predictors of utilization and expenditures.

Discussion

Prior literature using cross-sectional datasets has found that, adjusting for need, blacks and Latinos lag behind whites in any past year use of mental health care (e.g., Blanco et al. 2007; Alegria et al. 2008). We confirmed that these disparities also exist in initiation of an episode of care. Paying particular attention to the timing of mental health care episodes did little to change relative disparities in access to care. In both cross-sectional and longitudinal data analyses, whites were 1.5–1.7 times more likely to access (initiate) care than blacks and Latinos (cross-sectional results available upon request).

Blacks and Latinos with probable mental illness were significantly less likely than whites to have minimally adequate care, confirming prior findings (Young et al. 2001; Wang, Demier, and Kessler 2002; Alegria et al. 2008; Stockdale et al. 2008). Our analysis of adequacy conditional on initiation found no disparities, suggesting that adequacy disparities are largely driven by disparities in initiation of care rather than the number of visits received once care was initiated. Efforts to reduce initiation disparities might focus on interventions to improve identification of clinical need among minorities, access to mental health systems of care in minority communities, and initial engagement in treatment by minorities.

Previous studies have found that blacks were more likely than whites to receive mental health care from a PCP (Cooper-Patrick et al. 1999; Miranda and Cooper 2004). By contrast, we found that blacks with an outpatient mental health visit had a higher percentage of events with a specialist and were more likely to initiate and terminate episodes with specialists. This difference in results could reflect our study’s nationally representative sampling frame versus previous studies that primarily collected information from samples in primary care clinics, or our focus on individuals that had already initiated mental health care. These results provide some reassurance that minorities that do access mental health care are benefitting from access to specialist care as much as whites. However, the rates of adequacy of care are low irrespective of racial/ethnic group, suggesting the need to improve the retention of mental health patients across the health care system. After initiation, less than one in three experienced adequate care, and 35 percent had an episode with only one visit. Similar to a prior study identifying frequent churning (McFarland and Klein 2005), we found 49 percent of respondents terminated and restarted mental health care over a 2-year period and that this group was significantly less likely than nonchurners to have an adequate care episode (results available upon request).

Latino episodes of care included a larger proportion of PCP mental health visits than did white episodes, perhaps due to Latinos’ greater enrollment in public insurance programs and the positive association between public insurance and use of PCP services. A quality of care concern arising from this pattern for Latinos is that PCPs delivering mental health treatment were less likely to provide referrals to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy than specialty providers (Leo et al. 1998; Sirey et al. 1999; Young et al. 2001; Stockdale et al. 2008) and may lack the resources and connections to provide optimal care for Latinos with more severe mental disorders.

Unlike prior cross-sectional studies that identified no disparities among the population already in treatment, we found black-white and Latino-white disparities in length of treatment, conditional on any treatment. The difference may be attributable to the churning of racial/ethnic minorities that is not picked up in cross-sectional data. Underlying reasons for these shorter episodes (and for disparities in initiation of care) include increased concern over losing pay from work (Ojeda and McGuire 2006), stigma surrounding mental health care (Schraufnagel et al. 2006), and lower satisfaction with care (Jackson et al. 2007).

Similar to a study of private claims data (Mark, Vandivort-Warren, and Miller 2012), a substantial percentage of the population irrespective of race/ethnicity received continuous psychotropic drug fills without an outpatient visit to monitor treatment, and whites were more likely than minority patients to have such episodes. We caution that these rates may be overstated if patients and providers discussed psychotropic drug use in an outpatient visit but did not report the visit as being for mental health reasons. However, significant white-black and white-Hispanic differences persisted in sensitivity analyses that allowed for this possibility (results available upon request). These differences in psychotropic drug use are consistent with previous studies identifying racial/ethnic disparities in antidepressant medication treatment (Harman, Edlund, and Fortney 2004; Miranda and Cooper 2004) and racial/ethnic minorities’ negative attitudes toward antidepressant medication (Cooper et al. 2003a; Givens et al. 2007). Disparities in initiation and intensity of mental health care might therefore be partly attributable to whites’ greater use of psychotropic drug use only. Closing this gap may not be as desirable as closing gaps in episodes of treatment that more successfully combine outpatient psychotherapy and prescription drug medications.

Blacks were more likely to have an episode of care that included a psychiatric ER or IP visit, a result consistent with prior studies, which show that ER and IP services are more frequently used by racial/ethnic minorities for psychiatric care (Hazlett et al. 2004; Samnaliev, McGovern, and Clark 2009). Blacks may be entering the mental health care system at a greater severity than whites, or utilizing more avoidable, costly hospitalizations. This is particularly concerning given that racial/ethnic minorities are also at greater risk for poor follow-up after ER or IP use (Schneider, Zaslavsky, and Epstein 2002; Virnig et al. 2004) and because timely follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness can reduce the duration of disability and the likelihood of recurrence (National Committee on Quality Assurance 2010).

There are limitations to the episode data used in this study. First, as described above, the exact timing of prescription drug fill dates is uncertain. However, we remain confident in the direction and magnitude of our findings because we expect that errors in prescription fill date imputations will not differ by racial/ethnic group. Second, the full extent of utilization behaviors for some individuals’ episodes of mental health care cannot be captured because respondents are only tracked for 2-year time periods. We have conducted numerous sensitivity analyses to account for left-and right-censoring of the data. We also expect that if a greater time window of data was available, more white mental health care visits would be identified and disparities would actually be larger than our findings. Third, given the lack of detail on the timing of treatment, mental health outcomes, and severity of illness, we are unable to rule out that disparities were due to overuse by whites rather than underuse by minority groups. Studies showing disparities in adequate care among the severely mentally ill allay this concern, but more work is warranted to disentangle overuse and appropriate use in these populations. Fourth, expenditures are based on payment levels as opposed to provider charges and may vary by insurance category. Because blacks and Latinos are more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid than whites, and because Medicaid typically has the lowest payment levels among payers, expenditure disparities may be overestimated. Fifth, the MEPS does not contain measures of mental health care preferences, which should be adjusted for according to the IOM definition of health care disparities. Sensitivity analyses adjusting for four MEPS measures that represent proxies for preferences (risk-taking, worth of health insurance, and ability to overcome illness without medical help) produced results that were no different in direction and significance than our main findings. Sixth, selecting the approximately 11 percent of respondents with probable mental health care need based on the K-6 and PHQ-2 instruments is likely to miss a significant percentage of individuals that would be identified with a mental illness if structured diagnostic instruments were available in the MEPS. In particular, this raises the possibility that mentally ill individuals with low levels of distress and depressive symptoms are underrepresented in the study population.

Despite these limitations, this study provides evidence that disparities in access and adequacy of mental health care exist among individuals with probable mental illness, that racial/ethnic minorities have episodes of care with shorter duration than whites, and that blacks are more likely than whites to have an episode of care that includes a psychiatric ER or IP visit. Longitudinal studies that track the mental health consequences of these disparities are needed, as are interventions that improve initiation and retention in care, and more closely monitor dosing and side effect profiles among those with psychotropic drug prescriptions. Continued emphasis needs to be placed on reducing disparities in access to care that persist despite major national disparities reduction efforts (IOM 2002; US DHHS 2000). Improvements in mental health care for racial/ethnic minorities may come as a result of implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which will likely improve insurance coverage for ethnic/racial minority patients (Clemans-Cope et al. 2012) and increase overall utilization of mental health care (Garfield et al. 2011). However, a focus on disparities reduction is needed during ACA implementation as increased overall demand (Hanchate et al. 2012) and continued language, cultural, and socioeconomic barriers to care (Alegria et al. 2008) could actually cause an exacerbation of access and quality disparities.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: The project was supported by the National Institutes of Health NIMH grant R01 MH09 1042.

Disclosures

None.

Disclaimers

This paper represents the views of the authors, and no official endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred.

Notes

We have chosen to make two modifications to the definition of racial/ethnic disparities in the IOM’s Unequal Treatment report. In the report (p. 3), a health care disparity is defined as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors, or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” Our modified definition defines disparities as differences that are not due to clinical appropriateness and need or patient preferences. This matches more closely with Figure S-1 (p. 4) and follows the normative claim that differences in quality due to access-related factors should be considered to be a disparity. Second, we apply this definition to measures of quality (minimally adequate care) as well as other utilization variables (any utilization, mental health care expenditures) with the rationale that excluding differences due to clinical appropriateness, need, and patient preferences is equally relevant when assessing disparities in these other aspects of mental health care.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Coefficient Estimates from Models of Episodes of Mental Health Care among Those with Probable Mental Illness in Initiation and Follow-Up Phase.

Coefficient Estimates from Models of Episodes of Mental Health Care among Those with Probable Mental Illness in Follow-Up and Termination Phases.

Table S2a: Sensitivity Analysis: Episode Initiation.

Table S2b: Sensitivity Analysis: Adequate.

Table S2c: Sensitivity Analysis: RX Only.

Table S2d: Sensitivity Analysis: Length.

Table S2e: Sensitivity Analysis: Visits.

Table S2f: Sensitivity Analysis: Expenditures.

Table S2g: Sensitivity Analysis: Proportion Specialist/PCP.

Table S2h: Sensitivity Analysis: ER/IP within Episode.

Table S2i: Sensitivity Analysis: Termination.

Author Matrix.

References

- Afari N, Schmaling KB, Barnhart S, Buchwald D. Psychiatric Comorbidity and Functional Status in Adult Patients with Asthma. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2001;8(4):245–52. [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2008. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. MEPS HC-036: 1996–2009 Pooled Estimation File. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. MEPS HC-036BRR: 1996–2009 Replicates for Calculating Variances File. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012b. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, Cao Z, Chen C, Takeuchi D, Jackson J, Meng XL. Disparity in Depression Treatment among Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(11):1264–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Campbell S, Silbersweig D, Charlson M. ‘Vascular Depression’ Hypothesis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(10):915–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, Collins TC, Gordon HS, O’Malley K, Petersen LA, Sharf BF, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wray NP, Street RL., Jr Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Health Services: Bias, Preferences, or Poor Communication? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18(2):146–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ault-Brutus AA. Changes in Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Use and Adequacy of Mental Health Care in the United States, 1990-2003. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(6):531–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Patel S, Liu L, Jiang H, Lewis-Fernandez R, Schmidt A, Liebowitz M, Olfson M. National Trends in Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Care. Medical Care. 2007;45(11):1012–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca95d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who Is at Risk of Nondetection of Mental Health Problems in Primary Care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(6):381–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying Race-Ethnic Differences in Risk for Psychiatric Disorder in a USA National Sample. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(1):57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SH, Leslie D, Rosenheck R. Measuring Quality of Pharmacotherapy for Depression in a National Health Care System. Medical Care. 2004;42(6):532–42. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000128000.96869.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JL, Meiris DC. Building Bridges: Integrative Solutions for Managing Complex Comorbid Conditions. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2007;22(2S):5S. doi: 10.1177/1062860607299242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemans-Cope L, Kenney GM, Buettgens M, Carroll C, Blavin F. The Affordable Care Act’s Coverage Expansions Will Reduce Differences In Uninsurance Rates by Race and Ethnicity. Health Affairs. 2012;31(5):920–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins KS, Hall A, Neuhaus C. US Minority Health: A Chartbook. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. 1999:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, McGuire T, Miranda J. Measuring Trends in Mental Health Care Disparities, 2000–2004. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1533–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, McGuire TG, Zaslavsky AM. Measuring Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health Care: Methods and Practical Issues. Health Services Research. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1232–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, McGuire T, Zaslavsky A, Lock K. Comparing Methods of Racial and Ethnic Disparities Measurement across Different Settings of Mental Health Care. Health Services Research. 2010;45:825–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01100.x. (3): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, McGuire TG, Zaslavsky AM, Meara E. Adjusting for Health Status in Non-Linear Models of Health Care Disparities. Health Services Outcomes and Research Methodology. 2009b;9(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10742-008-0039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, McGuire T, Lock K, Zaslavsky A. Comparing Methods of Racial and Ethnic Disparities Measurement across Different Settings of Mental Health Care. Health Services Research. 2010;45(3):825–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L, Roter D, Johnson R, Ford D, Steinwachs D, Powe N. Patient-Centered Communication, Ratings of Care, and Concordance of Patient and Physican Race. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003a;139(11):907–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Wang NY, Ford DE. The Acceptability of Treatment for Depression among African-American, Hispanic, and White Primary Care Patients. Medical Care. 2003b;41:479–89. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Powe N, Jenckes M, Gonzales J, Levine D, Ford D. Identification of Patient Attitudes and Preferences Regarding Treatment of Depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(7):431–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, Steinwachs DM, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Mental Health Service Utilization by African Americans and Whites: The Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-up. Medical Care. 1999;37(10):1034. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan N, Meng XL, Lin JY, Chen C, Alegria M. Disparities in Defining Disparities: Statistical Conceptual Frameworks. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(20):3941–56. doi: 10.1002/sim.3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Cost Sharing and the Demand for Ambulatory Mental Health Services. American Psychologist. 1984;39(10):1195–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Teh C, Sorbero MJ, Mihalyo MJ, Kogan JN, Schuster J, Reynolds Iii CF, Stein BD. Predictors of Adequate Depression Treatment among Medicaid-Enrolled Adults. Health Services Research. 2010;45(1):302–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RL, Zuvekas SH, Lave JR, Donohue JM. The Impact of National Health Care Reform on Adults with Severe Mental Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):486–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens J, Houston T, Ford B, Van Voorhes D, Cooper L. Ethnicity and Preferences for Depression Treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):182–91. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of Depression and Diabetes Complications: A Meta-Analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63(4):619–30. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas-Wilson D, Cheadle A, Scheffler R. Demand for Mental Health Services: An Episode of Treatment Approach. Southern Economic Journal. 1989;56:219–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hanchate AD, Lasser KE, Kapoor A, Rosen J, McCormick D, D’Amore MM, Kressin NR. Massachusetts Reform and Disparities in Inpatient Care Utilization. Medical Care. 2012;50(7):569–77. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e319f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman J, Edlund M, Fortney J. Disparities in the Adequacy of Depression Treatment in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(12):1379–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett SB, McCarthy ML, Londner MS, Onyike CU. Epidemiology of Adult Psychiatric Visits to US Emergency Departments. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004;11(2):193–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin D, Volpe-Vartanian J, Alegría M. Discontinuation of Antidepressant Medication among Latinos in the USA. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;34(3):329–42. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Martin LA, Williams DR, Baser R. Use of Mental Health Services and Subjective Satisfaction with Treatment among Black Caribbean Immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):60–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2003. Key Facts: Race, Ethnicity and Medical Care” [accessed on June 13, 2012, 2003]. Available at http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/6069-index.cfm.

- Keeler EB, Manning WG, Wells KB. The Demand for Episodes of Mental Health Services. Journal of Health Economics. 1988;7(4):369–92. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(88)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SLT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-Item Depression Screener. Medical Care. 2003;41:1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo M, Raphael J, Sherry R, Jones AW. Referral Patterns and Recognition of Depression among African-American and Caucasian Patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20(3):175–82. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Machlin S, Cohen J, Elixhauser A, Beauregard K, Steiner C. Sensitivity of Household Reported Medical Conditions in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Medical Care. 2009;47(6):618–25. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195fa79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi E, Jensen GA. Diverging Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Physician Care: Comparing 2000 and 2007. Medical Care. 2012;50(4):327–34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark T, Vandivort-Warren R, Miller K. Mental Health Spending by Private Insurance: Implications for the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(4):313–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland BR, Klein DN. Mental Health Service Use by Patients with Dysthymic Disorder: Treatment Use and Dropout in a 7 1/2-Year Naturalistic Follow-up Study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TG, Alegria M, Cook BL, Wells KB, Zaslavsky AM. Implementing the Institute of Medicine Definition of Disparities: An Application to Mental Health Care. Health Services Research. 2006;41(5):1979–2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoefer CD, Zuvekas SH. New Estimates of the Demand for Physical and Mental Health Treatment. Health Economic. 2010;19(3):297–315. doi: 10.1002/hec.1476. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Cooper L. Disparities in Care for Depression among Primary Care Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(2):120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirandola M, Amaddeo F, Dunn G, Tansella M. The Effect of Previous Psychiatric History on the Cost of Care: A Comparison of Various Regression Models. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109(2):132–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multum Information Services. 2009. Lexicon–Drug Product & Disease Listings, 2009” [accessed on June 20, 2013]. Available at http://www.multum.com.

- National Committee on Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality: Reform, the Quality Agenda and Resource Use. Washington, DC: National Committee on Quality Assurance; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda V, McGuire T. Gender and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Use of Outpatient Mental Health and Substance Use Services by Depressed Adults. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2006;77(3):211–22. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringel JS, Sturm R. National Estimates of Mental Health Utilization and Expenditures for Children in 1998. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2001;28(3):319–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02287247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation of Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Samnaliev M, McGovern MP, Clark RE. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Treatment in Six Medicaid Programs. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20(1):165. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E, Zaslavsky A, Epstein A. Racial Disparities in the Quality of Care for Enrollees in Medicare Managed Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(10):1288–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, Roy-Byrne PP. Treating Minority Patients with Depression and Anxiety: What Does the Evidence Tell Us? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selden TM. The Within-Year Concentration of Medical Care: Implications for Family Out-of-Pocket Expenditure Burdens. Health Services Research. 2009;44(3):1029–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SM, Krishnan LL, Kunik ME, Ruiz P. Racial Disparities in Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression: A Literature Review. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2007;78(1):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9022-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Raue P. Predictors of Antidepressant Prescription and Early Use among Depressed Outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):690–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software Release 12.0 (Release Software) College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale SE, Lagomasino IT, Siddique J, McGuire T, Miranda J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Detection and Treatment of Depression and Anxiety among Psychiatric and Primary Health Care Visits, 1995–2005. Medical Care. 2008;46:668–77. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181789496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Young K. Research on Psychotherapy with Culturally Diverse Populations. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 1994;4:783–820. [Google Scholar]

- Tansella M, Micciolo R, Biggeri A, Bisoffi G, Balestrieri M. Episodes of Care for First-Ever Psychiatric Patients. A Long-Term Case-Register Evaluation in a Mainly Urban Area. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;167(2):220–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virnig B, Huang Z, Lurie N, Musgrave D, McBean AM, Dowd B. Does Medicare Managed Care Provide Equal Treatment for Mental Illness across Races? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(2):201. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Berglund P, Kessler R. Recent Care of Common Mental Disorders in the United States: Prevalence and Conformance with Evidence-Based Recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(5):284–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Demier O, Kessler R. Adequacy of Treatment for Serious Mental Illness in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(1):92–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus H, Wells K, Kessler R. Twelve-Month Use of Mental Health Services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;629–640:629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic Disparities in Unmet Need for Alcoholism, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2027–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Gonzalez H, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson J, Sweetman J, Jackson J. Prevalence and Distribution of Major Depressive Disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter K. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Young A, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The Quality of Care for Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH. Trends in Mental Health Services Use and Spending, 1987–1996. Health Affairs. 2001;20(2):214–24. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH. Prescription Drugs and the Changing Patterns of Treatment for Mental Disorders, 1996–2001. Health Affairs. 2005;24(1):195–205. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Coefficient Estimates from Models of Episodes of Mental Health Care among Those with Probable Mental Illness in Initiation and Follow-Up Phase.

Coefficient Estimates from Models of Episodes of Mental Health Care among Those with Probable Mental Illness in Follow-Up and Termination Phases.

Table S2a: Sensitivity Analysis: Episode Initiation.

Table S2b: Sensitivity Analysis: Adequate.

Table S2c: Sensitivity Analysis: RX Only.

Table S2d: Sensitivity Analysis: Length.

Table S2e: Sensitivity Analysis: Visits.

Table S2f: Sensitivity Analysis: Expenditures.

Table S2g: Sensitivity Analysis: Proportion Specialist/PCP.

Table S2h: Sensitivity Analysis: ER/IP within Episode.

Table S2i: Sensitivity Analysis: Termination.

Author Matrix.