Abstract

Daily affect is important to health and has been linked to cortisol. The combination of high negative affect and low positive affect may have a bigger impact on increasing HPA axis activity than either positive or negative affect alone. Financial strain may both dampen positive affect as well as increase negative affect, and thus provides an excellent context for understanding the associations between daily affect and cortisol. Using random effects mixed modeling with maximum likelihood estimation, we examined the relationship between self reported financial strain and estimated mean daily cortisol level (latent cortisol variable), based on six salivary cortisol assessments throughout the day, and whether this relationship was mediated by greater daily negative to positive affect index measured concurrently in a sample of 781 Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study participants. The analysis revealed that while no total direct effect existed for financial strain on cortisol, there was a significant indirect effect of high negative affect to low positive affect, linking financial strain to elevated cortisol. In this sample, the effects of financial strain on cortisol through either positive affect or negative affect alone were not significant. A combined affect index may be a more sensitive and powerful measure than either negative or positive affect alone, tapping the burden of chronic financial strain, and its effects on biology.

Keywords: financial strain, cortisol, positive affect, negative affect

Stress-induced stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is an adaptive neurobiological process with a range of protective body-wide effects. Yet, elevated or prolonged release of glucocorticoids, seen in those economically disadvantaged, can cause physiological `weathering' typical of diseases of aging (McEwen, 2007). For example, ambulatory and lab-induced elevations in cortisol levels have been significantly linked to various features of and risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Cagnacci et al., 2011; Hamer, O'Donnell, Lahiri, & Steptoe, 2010; Matthews, Schwartz, Cohen, & Seeman, 2006). Financial disadvantage is firmly established as a significant contributor to the development and progression of a wide range of chronic diseases and mortality (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008).

Affective states are acutely associated with ambulatory cortisol, the essential human glucocorticoid released from the adrenal gland. In studies that have examined both negative and positive affect during the day and their relationship to cortisol in the same study, greater negative affect covaries with increased cortisol in some studies, and in others, greater positive affect with lower cortisol (Adam, Hawkley, Kudielka, & Cacioppo, 2006; Brummett, Boyle, Kuhn, Siegler, & Williams, 2009; Nater, Hoppmann, & Klumb, 2010). Inconsistent findings may result from the fact that while negative and positive affective states are negatively correlated, they can co-occur (Larsen, McGraw, & Cacioppo, 2001), and that a combined affect index, i.e. the balance between participants' ratings of negative and positive affective states, may drive cortisol levels. The current study investigates this possibility, that an affect index integrating information from two opposing affective states is associated with cortisol measured at several time points across a day for each individual.

We examined these associations within the context of financial strain. Of growing interest is the role that financial strain plays in disease pathogenesis (Georgiades, Janszky, Blom, Laszlo, & Ahnve, 2009; Puterman, Adler, Matthews, & Epel, 2012; Rios & Zautra, 2011; Steptoe, Brydon, & Kunz-Ebrecht, 2005; Szanton et al., 2008; Szanton, Thorpe, & Whitfield, 2010). Financial strain has been previously related to elevated cortisol over the course of a day (Grossi, Perski, Lundberg, & Soares, 2001), providing an important context within which to examine how financial strain may indirectly impact daily cortisol through daily affect - and in particular a negative to positive affect index.

Method

Procedure

During 1985–1986, CARDIA recruited 5115 participants, aged 18 to 30 years, at four sites, balanced for race, sex, age, and education, and assessments were conducted at study entry and eight follow-up years up to 25 years. The current study reports data from a sub-study at the year-15 follow up at the Chicago, Illinois, and Oakland, California, sites (Cohen et al., 2006). Site institutional review committee approval and informed consent were obtained. Participants from the Chicago (N = 615) and Oakland (N = 721) sites who lived within 50 miles of the site were invited to participate in the sub-study following their main study visit. Of those eligible, 836 (62.6%) consented, of which 806 returned salivary cortisol samples and the time each sample was collected. Twenty-five participants who woke up after 11 AM (between 11:15 AM and 11:00 PM) were excluded. The present analysis includes the remaining 776 participants. Sub-study participants had lower education and income and higher body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and diastolic and systolic blood pressure than those who did not participate in the sub-study.

Measures

Cortisol

At the end of year 15 clinic visit, participants received materials and instructions for ambulatory cortisol collection. Samples were collected six times on one weekday: at awakening, 45 minutes, 2.5 hours, 8 hours, and 12 hours after awakening, and at bedtime. Participants were told not to eat, brush their teeth, or drink liquids for at least 15 minutes before samples. Alarm watches (preset to usual wakeup time) reminded participants to collect samples. Nine samples with levels below the minimum detectable level (0.7 nmol/L) were assigned values of 0.5 nmol/L. Intra- and interassay variabilities were less than 12%. Cortisol values were natural log transformed. One hundred and fifty-nine of 4,697 cortisol samples were excluded due to sample collection outside the appropriate windows. For more information on sample collection, storage, assay and exclusion criteria, see Cohen et al. (Cohen et al., 2006).

Financial Strain

In response to, “How hard is it for you (and your family) to pay for the very basics like food, medical care, and heating?” participants selected 1= very hard, 2 = hard, 3 = somewhat hard, or 4 = not very hard. Financial strain was recoded: very hard and hard as high strain (`1'), and somewhat and not very hard as low (`0') (Puterman et al., 2012).

Negative to Positive Affect Index

At each cortisol sampling, Participants recorded the extent to which they were currently (1) `happy, excited, content' and (2) `worried, anxious, fearful' on a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3). For each time point, negative to positive affect index was calculated by subtracting positive from negative affect. The intraclass correlation for the six reports of affect index made on a single day was .48, indicating that approximately half of the total variation is attributable to differences between participants in their average level of affect index, and half to fluctuations over the day.

Statistical Approach

Descriptive statistics and t-test and chi-square test comparisons between those high and low in financial strain were examined. Mixed effects models (with the intercept, time since waking, and grand-centered affect treated as random effects [with unstructured covariance matrix], other variables treated as fixed effects) with maximum likelihood estimation were used to test the (1) associations between financial strain and the person-specific intercepts (path X → Y, or `c', in typical mediation models) and (2) indirect effect of financial strain on cortisol through negative to positive affect index (paths `a' and `b' in typical mediation, X → M, and M → Y, respectively). We also examined whether either positive or negative affect independently mediates the financial strain-cortisol relationship. To test indirect effects `a*b', bootstrapping was employed (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, 2006), using the online tool to create 95% confidence intervals for the a*b pathway (http://www.quantpsy.org/medmc/medmc.htm). Bootstrap testing of mediation hypotheses is a preferable approach to mediation because it avoids the problem that the sampling distribution of the indirect effect is not normally distributed (Bauer et al., 2006). As noted by Preacher and Hayes (2004), indirect effects can exist even when there is no evidence for a significant total effect. Bootstrapping procedures use resampling procedures to test and retest a large number of times the indirect effect of X → M and M → Y to establish confidence intervals of the observed indirect effect. This is the same as the Monte Carlo method with real, not simulated, data and assumes that the parameter estimates are normally distributed (for a more in-depth read on bootstrapping procedures for mediation models, please see (Preacher & Hayes, 2008)). Due to the limited number of participants with high strain (N=35), only BMI and race, which significantly predicted the affect index and/or cortisol in mixed models, were included in the current study. Age, income, gender, and education were not included in the analyses. While we were interested in latent or estimated average affect index (person-specific intercepts) mediating the pathway from financial strain to latent or estimated average cortisol (person-specific intercepts), we accounted for the person-specific usual diurnal pattern of cortisol over the day, including the naturally occurring peak awakening response (a binary variable for the second cortisol sample at wake + 45 minutes) and natural declining slope across the day [hours since waking up at each sample centered around midday (8 hours from wakeup). Cortisol slopes did not vary as a function of either financial strain or affect and thus, we only modeled latent or estimated averages of cortisol (controlling for the slope). This is equivalent to completing analyses with area under the curve for the day, but maintains the advantage of mixed effects models with respect to the treatment of missing data. We subtracted 8 hours under the assumption that the typical person is awake for 16 hours and sleeps 8 hours. The average duration between the wake-up cortisol sample and the bedtime sample in this study was 16.5 hours. This allows us to interpret the random intercepts in the multilevel mixed models as average levels of the outcome variable over the waking period. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0.

Results

Descriptive statistics and comparisons between those high and low in financial strain are presented in Table 1. Compared to those with low financial strain (94.5% of sub-study sample), those with high strain were more likely to be black, have lower income and education, and greater BMI. Those high in financial strain also experienced significantly greater negative to positive affect index at 8 and 12 hours after wakeup and at bedtime. When affective states and cortisol levels were averaged across the full day of sampling, high financially strained participants had elevated daily negative affect (p = .04) and negative to positive affect (p = .04) compared to those with low strain. Mean negative affect for the entire day was significantly inversely related to mean positive affect [r (776) = −.31, p < .001]. PA and NA were negatively related at each time period; the inverse relationship was smallest at waking, r = −.l8, and ranged at different times of the day up to r = −.33, with no consistent time pattern. See Table 2 for correlations between negative and positive affect at each time point. However, only the negative to positive affect index score was significantly related to mean level of cortisol across the whole day [r (776) = .08, p = .03].

Table 1.

Demographics, Affect Discrepancy and Cortisol Levels, by Financial Strain.

| Baseline Financial strain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| All (N =776) | Low (N =741) | High (N =35) | |

|

|

|||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 39.95 (3.64) | 39.96 (3.66) | 39.82 (3.47) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 327 (42) | 316 (43) | 10 (29) |

| White, No (%)* | 355 (46) | 345 (47) | 10 (29) |

| Education (years), mean (SD)* | 14.89 (2.44) | 14.95 (2.43) | 13.63 (2.23) |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD)* | 29.30 (7.34) | 29.06 (7.01) | 34.47 (11.42) |

| Negative to Positive Affect Index | |||

| Wake, Mean (SD) | −0.43 (1.09) | −0.43 (1.09) | −0.40 (1.12) |

| +45 minutes, Mean (SD) | −0.70 (1.05) | −0.71 (1.04) | −0.49 (1.09) |

| + 2.5 hours, Mean (SD) | −0.82 (1.09) | −0.83 (1.08) | −0.49 (1.15) |

| + 8 hours, Mean (SD)* | −0.83 (1.14) | −0.85 (1.14) | −0.46 (1.20) |

| + 12 hours, Mean (SD)* | −0.84 (1.15) | −0.86 (1.14) | −0.42 (1.37) |

| Bedtime, Mean (SD)* | −0.92 (1.06) | −0.94 (1.04) | −0.47 (1.24) |

| Average for the day, Mean (SD)* | −0.75 (0.84) | −0.76 (0.83) | −0.46 (0.91) |

| Cortisol (nmol/L)+ | |||

| Wake, Mean (SD) | 20.39 (16.43) | 20.09 (16.01) | 25.09 (21.66) |

| +45 minutes, Mean (SD) | 25.65 (15.80) | 25.60 (15.61) | 24.89 (15.89) |

| + 2.5 hours, Mean (SD) | 15.05 (12.38) | 14.78 (11.63) | 18.71 (19.07) |

| + 8 hours, Mean (SD) | 10.46 (11.99) | 10.32 (11.81) | 13.39 (15.27) |

| + 12 hours, Mean (SD) | 7.02 (8.63) | 6.78 (7.65) | 12.18 (20.11) |

| Bedtime, Mean (SD) | 7.49 (11.13) | 7.39 (10.98) | 9.55 (14.07) |

| Average for the day, Mean (SD) | 14.56 (9.22) | 14.33 (8.64) | 17.38 (12.35) |

Note:

p ≤ .05, significant differences between high and low financially strained participants.

analyses with cortisol as outcome for t-tests used natural log transformed cortisol.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations for negative and positive affect for each of the 6 time points across the day of reporting.

| Wake | +45 Minutes | +2.5 hours | + 8 hours | +12 hours | Bedtime | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | PA | NA | PA | NA | PA | PA | PA | NA | PA | NA | PA | ||

| Wake | NA | - | −.18*** | .60*** | −.18*** | .43*** | −.13*** | .32*** | −.09* | .35*** | −.09* | .39*** | −.13*** |

| PA | - | −.15*** | .61*** | −.15*** | .45*** | −.16*** | .36*** | −.10** | .37*** | −.08* | .38*** | ||

| +45 min. | NA | - | −.26*** | .60*** | −.25*** | .49*** | −.13*** | .49*** | −.15*** | .42*** | −.15*** | ||

| PA | - | −.18*** | .61*** | −.18*** | .48*** | −.16*** | .44*** | −.14*** | .40*** | ||||

| +2.5 hrs. | NA | - | −.27*** | .54*** | −.15*** | .47*** | −.15*** | .38*** | −.10* | ||||

| PA | - | −.23*** | .56*** | −.20*** | .50*** | −.19*** | .45*** | ||||||

| + 8 hrs. | NA | - | −.33*** | .55*** | −.21*** | .46*** | −.13*** | ||||||

| PA | - | −.21*** | .54*** | −.19*** | .50*** | ||||||||

| +12 hrs. | NA | - | −.30*** | .52*** | −.17*** | ||||||||

| PA | - | −.17*** | .54*** | ||||||||||

| Beditime | NA | - | −.26*** | ||||||||||

| PA | - | ||||||||||||

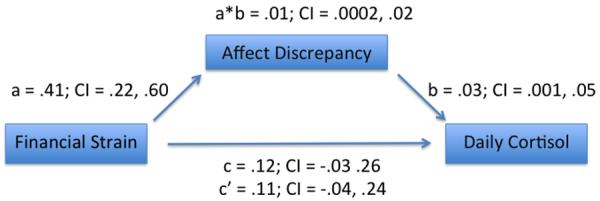

Mixed model analyses revealed that participants high (versus low) in financial strain did not have significantly higher cortisol (B= 0.12, SE = .07, p = .11; path c), after adjustment for covariates. Financial strain was unrelated to positive affect (B= −0.15, SE = .09, p = .12), but significantly related to negative affect (B= .20, SE = .09, p = .02), and affect index (B= 0.35 SE = .14, p < .02; path a) over the day. In separate models, positive affect (B= −0.05, SE = .02, p = .001), negative affect (B= 0.03, SE = .02, p = .048), and negative to positive affect index (B= 0.04, SE = .01, p = .001) were each significantly related to higher cortisol, with financial strain in the model as a covariate (paths b). Although, as previously noted, the association of financial strain with cortisol was not significant (p = .12, controlling for BMI and race), bootstrapping indicated a significant a*b indirect effect of financial strain on cortisol through negative to positive affect index, as seen in Figure 1. To interpret this indirect effect, financially strained individuals, compared to those lower in strain, have an average .35 unit significant increase in negative to positive affect index, which in turn is related to an average 4% significant increase in cortisol.

Figure 1.

Indirect Effects of Financial Strain on Daily Cortisol Output Through Negative to Positive Affect Index

Note. Bootstrapping indicated a significant a*b indirect effect of financial strain on cortisol through negative to positive affect index (95% CI = .001, .027). There was no significant indirect effect for either positive (95% CI = −.019, .002) or negative affect (95% CI = −.000, .017).

Discussion

In the current study, we examined whether the effect of financial strain on daily cortisol output was mediated by the difference between co-occurring negative and positive affect. Results indicate that positive and negative affect are related to levels of cortisol across a day, supporting previous work on each affective state (Adam et al., 2006; Brummett et al., 2009; Nater et al., 2010). While financial strain was not directly associated with cortisol over a day or a flatter slope as has previously been described for lower income individuals (Cohen et al., 2006), financial strain was related to greater negative affect alone, and to greater negative to positive affect index in independent analyses. Furthermore, bootstrapping revealed that a significant indirect pathway through which those experiencing financial strain may ultimately have elevated cortisol levels may be, in part, attributed to the combination of higher negative affect and lower positive affect at the same time, repeatedly, over the day. This effect was unique to the difference between negative and positive affect, as neither positive nor negative affective state alone was a significant mediator.

At any one point, people experience varying levels of positive and negative affect, and while the two are inversely related, both affective states are nonetheless somewhat independent from each other (Larsen et al., 2001). The ability to maintain some positive affect even in the face of distress is emerging as an important part of psychological and biological health. Maintaining positive affect can reduce stress-related physiological arousal (Aschbacher et al., 2012; L. Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998), and positive affect during stressful times is related to better adjustment on a daily basis (Zautra, Affleck, Tennen, Reich, & Davis, 2005). For many, the experience of financial strain is severe, and thus, examining the environmental or situational factors that curtail the experience of positive affect is of particular importance for future studies. The significant mediation of negative to positive affect index, of course, may also be partly due to greater power to detect the combined effect of high negative and low positive affect than either one alone.

It is important to note that we demonstrated that those financially strained have an average .35 unit significant increase in negative to positive affect index compared to those not strained, which in turn predicts an average 4% increase in mean daily cortisol. Previous work (Adam et al., 2006) has demonstrated that negative affect (tension and anger) is related to significant changes in cortisol slope (1% flatter per SD change in affect). Slope and mean levels may result in part from different underlying physiological regulation of the HPA axis (circadian regulation versus stress arousal), Differences in cortisol slope in a day do not necessarily mean higher mean cortisol, as one could have a flat slope with low values. Furthermore, at present, there are no standard trajectories or standard levels of average cortisol in a day that are understood to represent an unhealthy level that may promote dysregulation of other biological systems related to disease.

In addition to the role of cortisol in regulating metabolism via glucose production, cortisol has important regulatory effects on many systems, including cognitive, neural, autonomic and immune. Chronically elevated cortisol may strain these systems, leading to DNA alterations that alter protein production linked to accelerated cell aging and development of age-related diseases (Epel, 2009). Those financially strained feel more depressed, stressed, and vitally exhausted (Georgiades et al., 2009; Rios & Zautra, 2011). These effects may unfold daily through increases in negative affect and decreases in positive affect, resulting in a negative to positive affect index that co-occurs with, or even drives, cortisol elevations, as seen here. Of interest, while previous work has demonstrated that those with lower income and education have significantly flatter slopes than those with less socioeconomic disadvantage, the current analyses did not find a similar effect of self-reported financial strain on cortisol slope or average across the day. One previous study demonstrating that financial strain was related to cortisol across the day was conducted in a sample of chronically unemployed individuals (Grossi et al., 2001), thus differentiating the previous work from the current. Future studies should distinguish between objective and subjective components of socioeconomic disadvantage to examine whether different patterns of affective and biological outcomes emerge as a result.

While the intensity of affective states are important, increasing research directs our attention to the duration and frequency of affective states (Diener et al., 2009). Future studies should examine the intensity, frequency, and duration of a wider range of affective states, as well as the lagged effects of an affect index on cortisol. The current study could not examine these effects given the limited sampling that occurred (six times in one day) and limited affective states that were recorded. Thus, research could examine which emotions are triggered most by financial strain and examine the biological pathways that link specific affective states to HPA activation and reactivity of other systems.

Examining the effects of financial strain on emotional inertia (Suls, Green, & Hillis, 1998) and its ensuing role in elevated or blunted cortisol across the day could also prove a significant direction of future studies. The research on emotional inertia suggests that emotions are more likely to persist across time (i.e. higher emotional inertia) in those with greater psychological maladjustment (Kuppens, Allen, & Sheeber, 2010) and those predisposed to depression (Koval, Kuppens, Allen, & Sheeber, 2012). Yet, contextual factors seem to impact levels of inertia as well (Koval & Kuppens, 2012; Kuppens et al., 2010). To date, the extent to which financial strain predicts emotional inertia or how inertia is related to biological outcomes in the day remains unexplored.

In the current study, financial strain was not significantly related to cortisol yet appears to impact cortisol through altering the balance of positive and negative affective states experienced in a day. Recent advances in statistical modeling of mediation effects have highlighted the importance of distinguishing between mediation that requires a significant direct relationship between a predictor, X, and outcome, Y, versus testing indirect effects in the absence of a significant relationship. According to several researchers, the over-emphasis on full and partial mediation requiring the initial predictor `X' – in this case financial strain – to be significantly associated with the outcome `Y' – here, cortisol –limits theoretical developments. To summarize Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, and Petty (2011), the analysis of the direct effect X → Y is limited by several statistical considerations such as measurement precision, strength of the X:Y relationship, sample size, and suppressors. Furthermore, emphasizing the relationship of X → Y inhibits consideration of the equally important theoretical possibility that perhaps X predicts changes in a mediator M – here, negative to positive affect index – which then predicts a change in Y. By requiring either a significant X → Y or a significant drop in the effect c' when the mediator is included in the model, we lose sight of the multitude of factors that may be impacted by X that may in their own right be important in shifting Y.

Limitations and conclusions

An important limitation in the current study is the small number of participants reporting high financial strain (N=35), thus cautious extrapolation of the current findings to all financially strained individuals is necessary. Furthermore, this limited sample size and, especially, the small number of participants with high financial strain limits our ability to test whether differential patterns in affective and biological outcomes exist at varying levels of income and education, or by age, sex, or race.

Yet, these findings direct attention to the likely emotional burden of not being able to make ends meet, and the persistent, insidious way that low socioeconomic disadvantage “gets under the skin” to affect health. The psychological experience of prolonged stress about making ends meet may tip the emotional scale from positive to negative, with consequences for increased HPA arousal. Future investigations should examine whether the emotional burden of financial strain impacts other stress reactive biological systems. We've previously demonstrated in this sample that financial strain predicts elevated fasting glucose levels more than a decade later (Puterman et al., 2012). Elevations in glucocorticoids are related to increased risk for diabetes (American Diabetes Association, 2013). These results may help explain one mechanism by which financial hardship results in serious consequences for health.

Acknowledgement

We thank the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's continued support of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. The first author is supported by Award Number K99HL109247 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the MacArthur Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam EK, Hawkley LC, Kudielka BM, Cacioppo JT. Day-to-day dynamics of experience-cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(45):17058–17063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605053103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. US disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S67–S74. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschbacher K, Epel E, Wolkowitz OM, Prather AA, Puterman E, Dhabhar FS. Maintenance of a positive outlook during acute stress protects against pro-inflammatory reactivity and future depressive symptoms. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2012;26(2):346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological methods. 2006;11(2):142–163. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.11.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Kuhn CM, Siegler IC, Williams RB. Positive affect is associated with cardiovascular reactivity, norepinephrine level, and morning rise in salivary cortisol. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(4):862–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00829.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnacci A, Cannoletta M, Caretto S, Zanin R, Xholli A, Volpe A. Increased cortisol level: a possible link between climacteric symptoms and cardiovascular risk factors. Menopause. 2011;18(3):273. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f31947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Schwartz JE, Epel ES, Kirschbaum C, Sidney S, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic status, race, and diurnal cortisol decline in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68(1):41–50. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195967.51768.ea. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000195967.51768.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Biswas-Diener R, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S. New Measures of Well-Being. In: Diener E, editor. Assessing Well-Being. Vol. 39. Springer; Netherlands: 2009. pp. 247–266. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12. [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES. Psychological and metabolic stress: A recipe for accelerated cellular aging? Hormones-International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;8(1):7–22. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1217. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://000263924600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades A, Janszky I, Blom M, Laszlo KD, Ahnve S. Financial strain predicts recurrent events among women with coronary artery disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2009;135(2):175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.093. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi G, Perski A, Lundberg U, Soares J. Associations between financial strain and the diurnal salivary cortisol secretion of long-term unemployed individuals. Integrative Physiological & Behavioral Science. 2001;36(3):205–219. doi: 10.1007/BF02734094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, O'Donnell K, Lahiri A, Steptoe A. Salivary cortisol responses to mental stress are associated with coronary artery calcification in healthy men and women. European Heart Journal. 2010;31(4):424–429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp386. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval P, Kuppens P. Changing emotion dynamics: Individual differences in the effect of anticipatory social stress on emotional inertia. Emotion-APA. 2012;12(2):256. doi: 10.1037/a0024756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval P, Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber L. Getting stuck in depression: The roles of rumination and emotional inertia. Cognition & Emotion. 2012;26(8):1412–1427. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.667392. doi:10.1080/02699931.2012.667392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber LB. Emotional Inertia and Psychological Maladjustment. Psychological Science. 2010;21(7):984–991. doi: 10.1177/0956797610372634. doi:10.1177/0956797610372634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L. Fredrickson B, Levenson RW. Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition & Emotion. 1998;12(2):191–220. doi: 10.1080/026999398379718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JT, McGraw AP, Cacioppo JT. Can people feel happy and sad at the same time? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81(4):684–696. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K, Schwartz J, Cohen S, Seeman T. Diurnal cortisol decline is related to coronary calcification: CARDIA study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68(5):657–661. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000244071.42939.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87(3):873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. doi:DOI 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater UM, Hoppmann C, Klumb PL. Neuroticism and conscientiousness are associated with cortisol diurnal profiles in adults-Role of positive and negative affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(10):1573–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.017. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes A. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. doi:10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puterman E, Adler NE, Matthews KA, Epel ES. Financial Strain and Impaired Fasting Glucose: The Moderating Role of Physical Activity in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74(2):187–192. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182448d74. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182448d74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios R, Zautra AJ. Socioeconomic Disparities in Pain: The Role of Economic Hardship and Daily Financial Worry. Health Psychology. 2011;30(1):58–66. doi: 10.1037/a0022025. doi:10.1037/a0022025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, Petty RE. Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(6):359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Brydon L, Kunz-Ebrecht S. Changes in financial strain over three years, ambulatory blood pressure, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(2):281–287. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000156932.96261.d2. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000156932.96261.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Green P, Hillis S. Emotional reactivity to everyday problems, affective inertia, and neuroticism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24(2):127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Szanton SL, Allen JK, Thorpe RJ, Seeman T, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Effect of financial strain on mortality in community-dwelling older women. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(6):S369–S374. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Affleck GG, Tennen H, Reich JW, Davis MC. Dynamic approaches to emotions and stress in everyday life: Bolger and Zuckerman reloaded with positive as well as negative affects. Journal of personality. 2005;73(6):1511–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]