Abstract

Exposure to environmental stimuli conditioned to nicotine consumption critically contributes to the high relapse rates of tobacco smoking. Our previous work demonstrated that non-selective blockade of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) reversed the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking, indicating a role for cholinergic neurotransmission in the mediation of the conditioned incentive properties of nicotine cues. The present study further examined the relative roles of the two major nAChR subtypes, α4β2 and α7, in the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking. Male Sprague–Dawley rats were trained to intravenously self-administer nicotine (0.03 mg/kg/infusion, free base) on a fixed-ratio 5 schedule of reinforcement. A nicotine-conditioned cue was established by associating a sensory stimulus with each nicotine infusion. After nicotine-maintained responding was extinguished by withholding the nicotine infusion and its paired cue, reinstatement test sessions were conducted with re-presentation of the cue but without the availability of nicotine. Thirty minutes before the tests, the rats were administered the α4β2-selective antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) and α7-selective antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA). Pretreatment with MLA, but not DHβE, significantly reduced the magnitude of the cue-induced reinstatement of responses on the active, previously nicotine-reinforced lever. In different sets of rats, MLA altered neither nicotine self-administration nor cue-induced reinstatement of food seeking. These results demonstrate that activation of α7 nAChRs participates in the mediation of the conditioned incentive properties of nicotine cues and suggest that α7 nAChRs may be a promising target for the development of medications for the prevention of cue-induced smoking relapse.

Keywords: Conditioned stimulus, dihydro-β-erythroidine, methyllycaconitine, nicotine-seeking behaviour, reinstatement

Introduction

Tobacco smoking is a leading preventable cause of death in the United States. Currently, approximately 46 million American adults are smokers, representing approximately 20% of the population (Jemal et al., 2011). The majority of smokers (approximately 80%) who attempt to quit on their own return to smoking within 1 month. Each year, only 3% of smokers quit successfully (Benowitz, 2010; Shiffman et al., 1998). The high relapse rates of tobacco smoking present a formidable challenge for the success of smoking cessation efforts.

Drug-associated environmental cues critically contribute to the maintenance of, and relapse to, drug-seeking behaviour (Caggiula et al., 2001; Conklin et al., 2010; O′Brien et al., 1998). Tobacco smoking is particularly effective in establishing the incentive properties of associated environmental cues because smoking rituals contain more drug-cue pairings than other drugs of abuse. Smoking-related cues (e.g. the visual and olfactory stimuli associated with each puff) elicit subjective states that can trigger smoking and nicotine-seeking behaviour (Caggiula et al., 2001; Carter and Tiffany, 1999; Conklin et al., 2008; Cui et al., 2013; Garcia-Rodriguez et al., 2012; Gass et al., 2012; Miranda et al., 2008; Niaura et al., 1988; O′Brien et al., 1998; Parker and Gilbert, 2008; Rose, 2006; Tong et al., 2007; Winkler et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2009). Accumulating data from animal studies have demonstrated a significant contribution of nicotine-associated cues to the resumption of nicotine-seeking behaviour (Abdolahi et al., 2010; Chiamulera et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2005; Feltenstein et al., 2012; Fowler and Kenny, 2011; LeSage et al., 2004; Liu, 2010; Liu et al., 2006, 2008; Paterson et al., 2005; Shaham et al., 1997). Despite our increasing knowledge of the significance of cue exposure in triggering smoking relapse, little is known about the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie the motivational effects of nicotine cues.

Nicotine exerts its reinforcing actions by activating nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). To date, 12 nAChR subunits have been identified: nine α-subunits (α2–α10) and three β-subunits (β2–β4). These subunits assemble nAChRs into either heteromeric (α- and β-subunits) or homomeric (α-subunit only) combinations (Dani and Bertrand, 2007; Gotti and Clementi, 2004; McGehee and Role, 1995; Sargent, 1993). Although more nAChR subtypes continue to be identified, heteromeric α4β2- and homomeric α7-containing receptors are the most abundant and widespread, comprising more than 90% of the nAChRs in the brain (Albuquerque et al., 2009; Flores et al., 1992; Gotti and Clementi, 2004; Millar and Gotti, 2009; Sargent, 1993; Zoli et al., 1998). These two major nAChR subtypes show considerable differences in many aspects, including localization, density, functional characteristics (e.g. kinetics of activation, desensitization and recovery from desensitization), and Ca2+ permeability (Albuquerque et al., 1997; Alkondon and Albuquerque, 1993; Colquhoun and Patrick, 1997; Flores et al., 1992; Glennon and Dukat, 2000; Lippiello, 1989; McGehee and Role, 1995; Papke and Thinschmidt, 1998; Tribollet et al., 2001; Wonnacott et al., 2006). Accumulating evidence has established a pivotal role for α4β2 nAChRs in the mediation of the reinforcing actions of nicotine (Exley and Cragg, 2008; Levin et al., 2010; Mineur and Picciotto, 2008; O′Connor et al., 2010; Rezvani et al., 2010; Tapper et al., 2004; Tobey et al., 2012; Vieyra-Reyes et al., 2008; Watkins et al., 1999; Wonnacott et al., 2005). In contrast, research on α7 nAChRs has been inconclusive; most studies have not established the necessity of these receptors for nicotine reward (e.g. Grottick et al., 2000; Pons et al., 2008; Stolerman et al., 2004; van Haaren et al., 1999; Walters et al., 2006), whereas several other studies have reported the involvement of α7 nAChRs in nicotine reinforcement (Besson et al., 2012; Brunzell and McIntosh, 2012; Markou and Paterson, 2001).

Recently, our laboratory demonstrated that mecamylamine, a nonselective nAChR antagonist, effectively reversed the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour (Liu et al., 2007a). These results extended the role of nicotinic neurotransmission in the mediation of the reinforcing actions of nicotine to the conditioned motivational properties of nicotine-associated cues. Building on this line of research, the present study further targeted the α4β2 and α7 subtypes of nAChRs to determine their involvement in the mediation of the conditioned motivation exerted by nicotine cues. Specifically, the present study used an extinction—reinstatement model of relapse to examine the effects of the α4β2-selective antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) and α7 nAChR-selective antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA) on the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour.

Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague—Dawley rats (Charles River, USA), 201–225 g upon arrival, were used. The animals were individually housed in a humidity- and temperature-controlled (21–22°C) colony room on a reverse light/dark cycle (lights on 20:00 hours, lights off 08:00 hours). After 1 wk of habituation, the rats were placed on a food-restriction regimen (20 g chow/day) throughout the experiments, which allowed the rats to have consistent but low weight gain at approximately 85% of their free-feeding condition. The rats had unlimited access to water. The training and experimental sessions were conducted during the dark phase at the same time each day (09:00 hours–15:00 hours). All of the experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Self-administration apparatus

Experimental sessions were conducted in standard operant conditioning chambers located inside sound-attenuating, ventilated cubicles (Med Associates, USA). The chambers were equipped with two retractable response levers on one side panel, a 28 V white light above each lever, and a red house light on top of the chambers. Between the two levers was a food pellet trough. Intravenous nicotine injections were delivered by a drug delivery system with a syringe pump (model PHM100-10 r/min, Med Associates, USA). Experimental events and data collection were automatically controlled by an interfaced computer and software (Med-PC version IV, Med Associates, USA).

Lever-press training

To facilitate the learning of operant responding for nicotine self-administration (see below), the rats under-went lever-press training. One day after the beginning of the food-restriction regimen, the rats were placed in the experimental chambers, and the training sessions began with the introduction of the levers. Responding on the active lever was rewarded with the delivery of a food pellet (45 mg). The sessions lasted 1 h, with a maximum delivery of 45 food pellets on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule. After the rats learned to respond, the reinforcement schedule was increased to FR5. The training ended after the rats earned 45 food pellets on the FR5 schedule. Successful lever-press training with food pellets as reinforcers was achieved within 2–5 sessions.

Surgery

Intravenous catheterization was performed after food training. The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–3% in 95% O2 and 5% CO2). An indwelling catheter was inserted into the right external jugular vein. The catheters were constructed using a 15 cm piece of Silastic tubing (0.31 mm inner diameter, 0.63 mm outer diameter; Dow Corning Corporation, USA) attached to a 22-gauge stainless-steel guide cannula. The latter was bent and molded onto a durable polyester mesh (Plastics One, USA) with dental cement and became the catheter base. Through an incision on the rat’s back, the base was anchored underneath the skin at the level of the scapulae, and the catheter passed subcutaneously to the ventral lower neck region and inserted into the right jugular vein (3.5 cm). The animals were allowed at least 7 d to recover from surgery. During the recovery period, the catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml of sterile saline that contained heparin (30 U/ml) and Timentin (66.7 mg/ml) to maintain catheter patency and prevent infection. Thereafter, the catheters were flushed with heparinized saline before and after the experimental sessions.

Nicotine self-administration and conditioning training

After recovery from intravenous catheterization surgery, the rats were subjected to nicotine self-administration and conditioning training sessions. In the daily 1 h training sessions, the rats were placed in the operant conditioning chambers and connected to the intravenous drug infusion system. The sessions began with extension of the two levers and illumination of the red house light. Once the rats reached the FR requirement at the active lever, an infusion of nicotine (0.03 mg/kg, free base) was delivered in a volume of 0.1 ml in approximately 1 s, depending on the rats’ body weights. To establish a nicotine-conditioned cue, each nicotine infusion was paired with the presentation of an auditory/visual stimulus that consisted of a 5 s tone and 20 s illumination of the light above the active lever. A 20 s timeout period followed each nicotine infusion, during which time responses were recorded but not reinforced. An FR1 schedule was used for days 1–5, an FR2 schedule was used for days 6–8, and an FR5 schedule was used for the remaining days of the experiments. Throughout the experiments, responses at the inactive lever were recorded, but had no programmed consequences. Stable nicotine self-administration was considered to be established once the rats self-administered ≥10 infusions per session with ≤20% variation for at least three consecutive sessions. Four rats failed to meet the criterion and were eliminated from the subsequent experimental procedures.

Extinction

After the completion of the self-administration and conditioning training phase, the rats were subjected to extinction sessions. In the daily sessions, nicotine-maintained lever responding was extinguished by with-holding nicotine and its associated cue. Responses on the active lever resulted in the delivery of saline rather than nicotine, and the cue was not presented. The FR5 schedule and 20 s timeout period were still in effect for saline infusions. The criterion for extinction was three consecutive sessions in which the number of responses per session was ≤20% of the responses averaged across the last three sessions of the self-administration and conditioning training phase.

Reinstatement

One day after the final extinction session, reinstatement tests were performed, in which introduction of the two levers and illumination of the red house light signaled the beginning of the sessions. Immediately after the sessions began, a single response-noncontingent cue was presented to inform the rats of the availability of the nicotine cue. Throughout the test sessions, responses on the active lever on the FR5 schedule resulted in re-presentation of the cue and delivery of saline rather than nicotine. Responses on the inactive lever were recorded, but had no programmed consequences. The test sessions lasted 1 h.

Test 1, effects of DHβE and MLA on cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking

After completion of extinction phase, rats were divided into two groups in a pseudo-random manner (n = 10 each group) based on similar lever responses emitted during the self-administration and conditioning phases. Thirty minutes before the reinstatement test sessions, one group of rats was subcutaneously administered DHβE (0, 3 and 9 mg/kg), and the other group was intraperitoneally administered MLA (0, 2.5 and 10 mg/kg). The DHβE and MLA pretreatments were scheduled in a within-subjects Latin-square design in the respective groups. For both groups, the reinstatement test sessions were separated by two daily extinction sessions to determine the extinction baseline before each reinstatement test.

Test 2, effects of MLA on nicotine self-administration

Eight rats were used for testing effects of MLA on nicotine self-administration. After stable nicotine self-administration was established, the test sessions began. Thirty minutes before tests, MLA (0, 2.5 and 10 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally administered in a within-subjects Latin-square design. The test sessions were separated by two no-drug-treatment sessions.

Test 3, effects of MLA on cue-induced food seeking

Eight rats were trained to self-administer food pellets and a food-conditioned cue was established under conditions identical to that for nicotine rats, except that food pellets rather than nicotine infusions were delivered upon lever responses. After the food-maintained responses were extinguished, effects of MLA on cue-induced reinstatement of food seeking were examined. In the reinstatement test sessions, responses on the active lever resulted in presentations of the food cue on the FR5 schedule while there was no availability of food pellets. Thirty minutes before the test sessions, MLA (0, 2.5 and 10 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally administered in a within-subjects Latin-square design. The test sessions were separated by two extinction sessions.

Statistical analyses

The data are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. number of lever responses and nicotine infusions earned. The self-administration data averaged across the final three sessions were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The data obtained in the extinction phase were analysed using two-way repeated ANOVA with session as the within-subjects factor and antagonist as the between-subjects factor. The data collected from the reinstatement tests with the two antagonists were separately analysed using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with drug dose as the within-subjects factor. Differences among individual means were verified by subsequent Newman– Keuls post-hoc tests.

Results

Nicotine self-administration and extinction

The rats successfully acquired stable levels of nicotine self-administration in the 25 daily 1 h self-administration and conditioning training sessions. Averaged across the final three sessions, the rats (n = 20) emitted a mean±s.e.m. number of responses of 81.8±14.7 on the active lever and 9.3±2.2 on the inactive lever. The animals correspondingly self-administered 14.3±2.2 infusions of nicotine at a unit dose of 0.03 mg/kg/infusion. Because grouping the rats for the subsequent nicotine-seeking tests was performed in a pseudo-random manner, the two groups for the following reinstatement/antagonist test had similar levels of responses on the active lever (F1,18= 0.10, p=0.76) and number of nicotine infusions (F1,18= 0.09, p=0.81). Details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Similar lever-press response profiles in the two antagonist test groups either averaged across the final three sessions of the self-administration/conditioning phase or obtained from the last session of the extinction phase

| Group | DHβE (n=10) | MLA (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-administration/conditioning | ||

| Active lever responses | 82 ±16 | 79±13 |

| Inactive lever responses | 10 ±4 | 8±3 |

| Extinction | ||

| Active lever responses | 15 ±5 | 16±5 |

| Inactive lever responses | 7±3 | 6±3 |

In the extinction phase, although these two groups did not differ (F1,18 = 0.01, p = 0.93), there was a significant effect of sessions (F9,162 = 24.10, p < 0.0001). Responses on the active lever in the two groups of rats similarly decreased across the daily sessions, indicating extinction of nicotine-seeking responses. All of the rats reached the extinction criterion in 10 d. Table shows the numbers of lever responses in the last extinction session.

Effects of DHβE on cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour

As shown in Fig. 1, DHβE pretreatment did not change lever-press responses in the cue-induced reinstatement tests conducted after extinction. The one-way repeated-measure ANOVA of the number of active lever responses did not reveal a significant effect of DHβE dose (F2,18 = 0.51, p = 0.61). Responses on the inactive lever remained unchanged.

Fig. 1.

Effect of dihydro-β-erythroidine pretreatment on lever-press responses in the reinstatement test sessions in rats (n = 10). The data are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. number of lever responses made during the 1 h test sessions.

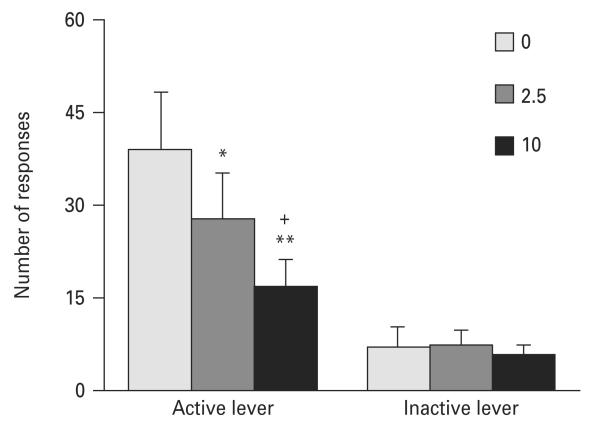

Effects of MLA on cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour

Figure 2 shows a suppressant effect of MLA pretreatment on the cue-induced reinstatement of responses on the active, previously nicotine-reinforced lever. The one-way repeated-measures ANOVA of the number of active lever responses revealed a significant effect of MLA dose (F2,18 = 13.23, p < 0.001). Further Newman–Keuls post-hoc tests confirmed significant differences in the number of active lever responses between the 2.5 mg/kg (p < 0.05) and 10 mg/kg (p < 0.01)doses of MLA and the saline control condition and between the 10 mg/kg (p < 0.05) and 2.5 mg/kg doses of MLA, indicating a dose-dependent suppressant effect of MLA pretreatment on the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking responses. However, responses on the inactive lever remained low and indistinguishable among the different dose conditions.

Fig. 2.

Effect of methyllycaconitine pretreatment on lever-press responses in the reinstatement test sessions in rats (n = 10). The data are expressed as the mean±sS.E.M. number of lever responses made during the 1 h test sessions. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significant difference from saline control condition (0); +p < 0.05, significant difference from 2.5 mg/kg.

Effects of MLA on nicotine self-administration

MLA pretreatment did not change lever responses for nicotine self-administration (Table 2). There was no significant effect of MLA dose on the number of responses on the active lever (F2,14 = 0.66, p = 0.53).

Table 2.

Methyllycaconitine pretreatment changed neither nicotine self-administration nor cue-induced reinstatement of food seeking. The numbers of responses on the active lever were presented

| Saline | 2.5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine self-administration (n=8) |

91 ±14 | 95±21 | 87±12 |

| Cue-induced food seeking (n=8) |

45±9 | 36±10 | 42±8 |

Effects of MLA on cue-induced reinstatement of food seeking

As shown in Table 2, lever responses made by the food-trained rats in the cue-induced reinstatement tests were not altered by pretreatment with MLA. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA of the number of active lever responses did not reveal a significant effect of MLA dose (F2,14 = 0.20, p = 0.82).

Discussion

Based on our previous work, in which nonselective blockade of nAChRs attenuated the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour (Liu et al., 2007a), the present study further examined the relative roles of α4β2 and α7 nAChRs in the behavioural motivational effects of nicotine-conditioned cues. The results demonstrated that the α7-selective antagonist MLA but not α4β2-selective antagonist DHβE effectively suppressed the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking responses. These results indicate that cholinergic neurotransmission via activation of the α7 subtype of nAChRs plays a role in the mediation of the conditioned incentive properties of nicotine cues measured in the extinction-reinstatement procedure. Therefore, manipulation of α7 nAChR activity may prove to be a promising target for the development of pharmacotherapies for the prevention of smoking relapse triggered by exposure to environmental cues.

In the reinstatement test sessions, responses on the previously nicotine-reinforced, active lever were significantly attenuated after MLA pretreatment, indicating a suppressant effect of MLA on cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour. The involvement of α7 nAChRs in the conditioned motivational effect of nicotine cues is specific because of the following reasons. Pretreatment with MLA changed neither responses on the inactive lever during these reinstatement tests nor nicotine self-administering responses tested in a different group of rats. In the sessions to test cue-induced reinstatement of food seeking, MLA pretreatment did not alter lever responses, which is consistent with our previous work demonstrating that nonselective antagonism of nAChRs by mecamylamine changed neither food self-administration nor food-seeking responses reinstated by re-presentation of a food-associated cue (Liu et al., 2007a), indicating that nAChRs may not critically participate in food reinforcement and its related associative learning process. Moreover, MLA at 10 mg/kg, the highest dose used in the present study, did not alter nicotine-enhanced lever pressing in response to presentation of an intrinsically reinforcing sensory stimulus (Liu et al., 2007b). Altogether, these data exclude the possibility that MLA nonspecifically impaired general locomotor activity, arousal state, the motivation to earn rewards, operant goal-directed behaviour and the conditioned effect of food-conditioned cues. Therefore, the present results demonstrate a specific suppressant effect of MLA on the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking and suggest that activation of α7 nAChRs may be required for the expression of conditioned incentive motivation induced by nicotine-related cues. A role for α7 nAChRs in the effects of nicotine cues is consistent with evidence obtained from studies that used other learning-assessment paradigms. For example, Quarta et al. (2009) found that MLA attenuated the discriminative stimulus effect of nicotine, and dopamine release in the striatal region appeared to be involved in this effect. The deletion of α7 nAChRs was reported to impair responses in an appetitive learning task established by a natural reward, sucrose (Keller et al., 2005). A recent study showed that activation of α7 nAChRs participated in trace eyeblink conditioning, a hippocampus-dependent conditioning process (Brown et al., 2010).

There have been several studies examining the issue of whether α7 nAChRs are required for the primary reinforcing effects of nicotine. Two earlier studies tested the effects of α7 nAChR blockade on operant intravenous nicotine self-administration. One study showed that MLA did not interfere with nicotine self-administration (Grottick et al., 2000), but the other study demonstrated a suppressant effect of MLA on nicotine self-administration (Markou and Paterson, 2001). Conditioned place preference studies negated a possible role for α7 nAChRs in the mediation of nicotine reward. For example, mice that were either treated with MLA or deficient in α7 nAChRs developed nicotine-induced conditioned place preference at a level similar to their control counterparts (Grabus et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2006). A recent study, in which mice self-administered nicotine directly into the ventral tegmental area, showed that MLA pretreatment decreased self-administration responses in wildtype animals, whereas α7 nAChR knockout mice self-administered less nicotine only when nicotine unit doses were low (Besson et al., 2012). In contrast, Brunzell and McIntosh (2012) found that the α7 nAChR-selective antagonist α-conotoxin ArlB [VIIL,VI6D], when microinjected into rat nucleus accumbens shell and anterior cingulate cortex, significantly increased nicotine self-administration behaviour under a progressive-ratio schedule of reinforcement. The results of the present study showing a lack of effect of MLA pretreatment on lever responses for nicotine self-administration suggest that activation of α7 nAChRs may not play an indispensible role in the mediation of nicotine primary reinforcement.

Although α4β2 nAChRs play a pivotal role in the mediation of the reinforcing effects of nicotine, neurotransmission via these receptors is not required for the expression of the behavioural motivational effects of nicotine cues. In the present study, DHβE pretreatment did not interfere with the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking responses. The doses used should be sufficient to antagonize the receptors because such a dose range has often been used in the literature, including self-administration studies (e.g. Grottick et al., 2000; Paterson et al., 2010; Watkins et al., 1999) and our own work, that showed that 1–9 mg/kg DHβE effectively decreased nicotine-enhanced lever-pressing in response to the presentation of a reinforcing stimulus (Liu et al., 2007b). Therefore, cholinergic neurotransmission via activation of α4β2 nAChRs does not appear to be required for the mediation of conditioned incentive motivation elicited by nicotine cues. These results are consistent with three other studies published recently. Varenicline, a partial agonist at α4β2 nAChRs, had no effect on the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking assessed using similar extinction—reinstatement procedures in rodents (O’Connor et al., 2010; Wouda et al., 2011) and did not change cue-specific craving in smokers (Gass et al., 2012). However, varenicline after a longer pretreatment time did reduce the ability of nicotine cue to reinstate nicotine seeking in rats (Le Foll et al., 2012) and in a 3 wk treatment regimen in smokers without abstinence diminish smoking cue-elicited craving (Franklin et al., 2011). Interestingly, Wouda et al. (2011) found that varenicline effectively attenuated the cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behaviour. Together with another report (Guillem and Peoples, 2010), in which varenicline at lower doses reduced the cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking, these results suggests a role for α4β2 nAChRs in the motivational effects of cues conditioned to alcohol and cocaine but not nicotine. Elucidating such a significant difference between nicotine and other drugs of abuse and the involvement of associative learning and memory processes warrants future studies.

Notably, α4β2 and α7 nAChRs play differential roles in nicotine-induced reinforcement and the conditioned reinforcement induced by nicotine cues. α4β2 nAChRs appear to participate in nicotine reinforcement but not conditioned reinforcement induced by nicotine cues, whereas α7 nAChRs do the opposite. The differential involvement of these two nAChR subtypes indicates a dissociation of the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie the primary reinforcing actions of nicotine and secondary reinforcement induced by nicotine cues. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study. O’Connor et al. (2010) reported that the α4β2 nAChR partial agonist varenicline suppressed nicotine self-administration and the reinstatement of nicotine seeking induced by nicotine priming and the combination of nicotine and its cue but did not affect reinstatement induced by the nicotine cue alone. Such a dissociation was also revealed at the opioidergic neurotransmission level. Our previous study showed that nonselective blockade of opioid receptors by naltrexone attenuated the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking but had no effect on nicotine self-administration (Liu et al., 2009). A similar dissociation was found with other drugs of abuse and signaling pathways. For example, we reported that the inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis attenuated the conditioned reinstatement of ethanol seeking but not the primary reinforcing actions of ethanol (Liu and Weiss, 2004). Similarly, Martin-Fardon et al. (2007) found that antagonism of orphan sigma-1 receptors reversed cue-induced cocaine-seeking but did not change cocaine self-administration. Even in cases in which one drug produced effects on both conditioned and primary reinforcement, the sensitivity of the effect was different. For example, responding motivated by stimuli conditioned to cocaine was more sensitive to glutamate antagonists than behaviour maintained by cocaine itself (Baptista et al., 2004; Newman and Beardsley, 2006). Therefore, the conditioned incentive properties of nicotine cues and primary reinforcing actions of nicotine may be mediated by different neurobiological substrates.

Finally, the brain exhibits wide expression of α7 nAChRs, with dense distribution in regions responsible for associative learning and memory, such as the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, hippocampus, ventral tegmental area and cortex (Clarke et al., 1985; Fu et al., 2000; Jones and Wonnacott, 2004; Quik et al., 2000). Specifically, in addition to post-synaptic regions, α7 nAChRs are located at presynaptic and perisynaptic sites and implicated in the regulation of the release of several neurotransmitters, including dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine and glutamate (Barik and Wonnacott, 2009; McGehee et al., 1995; Schilstrom et al., 2003). Chronic nicotine self-administration has been found to upregulate α7 nAChRs in these regions in rodents (Marks et al., 1983; Pakkanen et al., 2005; Pauly et al., 1991; Rasmussen and Perry, 2006; Small et al., 2010). An increasing number of animal studies, including our own work, have identified some of the neuropharmacological substrates responsible for the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking. The behavioural motivational effect of nicotine cues was suppressed by antagonists selective for dopamine D1, D2 (Liu et al., 2010) and D3 receptors (Khaled et al., 2010), noradrenergic α1 (Forget et al., 2010) and β receptors (Chiamulera et al., 2010), cannabinoid CB1 receptors (Cohen et al., 2005; De Vries et al., 2005; Shoaib, 2008), metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) 1 (Dravolina et al., 2007) and mGluR5 (Bespalov et al., 2005), ionotropic glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR) (Pechnick et al., 2011) and T-type Ca2+ channels (Uslaner et al., 2010). The behavioural motivational effect of nicotine cues was also suppressed by a nonselective opioid receptor antagonist (Liu et al., 2009), mGluR2/3 agonist (Liechti et al., 2007), GABAB receptor agonist (Paterson et al., 2005) and α-type peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist (Panlilio et al., 2012). Interestingly, Li et al. (2012) found that interruption of α7 nAChR-NMDAR complex formation blocked cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking responses. These studies, together with the present demonstration of α7 nAChR involvement, highlight an array of biological signaling pathways that are responsible for the mediation of the cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour and provide insights into the mechanisms that underlie the conditioned incentive properties of nicotine cues. Building on our own work that demonstrated the involvement of both dopamine D1/D2 receptors and α7 nAChRs in the effects of nicotine-related cues (Liu et al., 2010 and this study) and evidence of the significance of ventral striatal (especially the nucleus accumbens core) dopaminergic neurotransmission in the conditioned motivational processes associated with other drugs of abuse (e.g. cocaine, heroin and alcohol) and natural rewards (e.g. food) (Alvarez-Jaimes et al., 2008; Bossert et al., 2007; Cacciapaglia et al., 2012; Chaudhri et al., 2010; Floresco et al., 2008; Fuchs et al., 2004; Hutcheson et al., 2001), a signaling cascade from α7 nAChRs to dopamine receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens region may be hypothesized to mediate the motivational effect of nicotine cues. This hypothesis remains to be tested.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DA017288 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and funds from the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behaviour, University of Mississippi Medical Center. The author thanks Courtney Jernigan, Laura Beloate, Ramachandram Avusula, Treniea Tolliver, and Trisha Patel for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Statement of Interest

None.

References

- Abdolahi A, Acosta G, Breslin FJ, Hemby SE, Lynch WJ. Incubation of nicotine seeking is associated with enhanced protein kinase A-regulated signaling of dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein of 32 kDa in the insular cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:733–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Schrattenholz A, Maelicke A. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on hippocampal neurons: distribution on the neuronal surface and modulation of receptor activity. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 1997;17:243–266. doi: 10.3109/10799899709036607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. I. Pharmacological and functional evidence for distinct structural subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1455–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Jaimes L, Polis I, Parsons LH. Attenuation of cue-induced heroin-seeking behaviour by cannabinoid CB1 antagonist infusions into the nucleus accumbens core and prefrontal cortex, but not basolateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2483–2493. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista MA, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Preferential effects of the metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 on conditioned reinstatement vs. primary reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a potent conventional reinforcer. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4723–4727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik J, Wonnacott S. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of action of nicotine in the CNS. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;192:173–207. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2295–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bespalov AY, Dravolina OA, Sukhanov I, Zakharova E, Blokhina E, Zvartau E, Danysz W, van Heeke G, Markou A. Metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR5) antagonist MPEP attenuated cue- and schedule-induced reinstatement of nicotine self-administration behaviour in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(Suppl. 1):167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson M, David V, Baudonnat M, Cazala P, Guilloux JP, Reperant C, Cloez-Tayarani I, Changeux JP, Gardier AM, Granon S. Alpha7-nicotinic receptors modulate nicotine-induced reinforcement and extracellular dopamine outflow in the mesolimbic system in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;220:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Poles GC, Wihbey KA, Koya E, Shaham Y. Differential effects of blockade of dopamine D1-family receptors in nucleus accumbens core or shell on reinstatement of heroin seeking induced by contextual and discrete cues. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12655–12663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3926-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KL, Comalli DM, De Biasi M, Woodruff-Pak DS. Trace eyeblink conditioning is impaired in alpha7 but not in beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:166. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2010.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, McIntosh JM. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors modulate motivation to self-administer nicotine: implications for smoking and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1134–1143. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciapaglia F, Saddoris MP, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Differential dopamine release dynamics in the nucleus accumbens core and shell track distinct aspects of goal-directed behaviour for sucrose. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(5–6):2050–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:515–530. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Sahuque LL, Schairer WW, Janak PH. Separable roles of the nucleus accumbens core and shell in context- and cue-induced alcohol-seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:783–791. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamulera C, Tedesco V, Zangrandi L, Giuliano C, Fumagalli G. Propranolol transiently inhibits reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:389–395. doi: 10.1177/0269881108097718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PB, Schwartz RD, Paul SM, Pert CB, Pert A. Nicotinic binding in rat brain: autoradiographic comparison of [3H]acetylcholine, [3H]nicotine, and [125I]-alpha-bungarotoxin. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1307–1315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01307.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C, Perrault G, Griebel G, Soubrie P. Nicotine-associated cues maintain nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats several weeks after nicotine withdrawal: reversal by the cannabinoid (CB1) receptor antagonist, rimonabant (SR141716) Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:145–155. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun LM, Patrick JW. Pharmacology of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;39:191–220. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Robin N, Perkins KA, Salkeld RP, McClernon FJ. Proximal vs. distal cues to smoke: the effects of environments on smokers’ cue-reactivity. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:207–214. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Perkins KA, Robin N, McClernon FJ, Salkeld RP. Bringing the real world into the laboratory: personal smoking and nonsmoking environments. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Versace F, Engelmann JM, Minnix JA, Robinson JD, Lam CY, Karam-Hage M, Brown VL, Wetter DW, Dani JA, Kosten TR, Cinciripini PM. Alpha oscillations in response to affective and cigarette-related stimuli in smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:917–924. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, de Vries W, Janssen MC, Schoffelmeer AN. Suppression of conditioned nicotine and sucrose seeking by the cannabinoid-1 receptor antagonist SR141716A. Behav Brain Res. 2005;161:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravolina OA, Zakharova ES, Shekunova EV, Zvartau EE, Danysz W, Bespalov AY. mGlu1 receptor blockade attenuates cue- and nicotine-induced reinstatement of extinguished nicotine self-administration behaviour in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Cragg SJ. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors: a dynamic and diverse cholinergic filter of striatal dopamine neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 1):S283–297. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Ghee SM, See RE. Nicotine self-administration and reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in male and female rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CM, Rogers SW, Pabreza LA, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ. A subtype of nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is composed of alpha 4 and beta 2 subunits and is up-regulated by chronic nicotine treatment. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, McLaughlin RJ, Haluk DM. Opposing roles for the nucleus accumbens core and shell in cue-induced reinstatement of food-seeking behaviour. Neuroscience. 2008;154:877–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget B, Wertheim C, Mascia P, Pushparaj A, Goldberg SR, Le Foll B. Noradrenergic alpha1 receptors as a novel target for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1751–1760. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CD, Kenny PJ. Intravenous nicotine self-administration and cue-induced reinstatement in mice: effects of nicotine dose, rate of drug infusion and prior instrumental training. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin T, Wang Z, Suh JJ, Hazan R, Cruz J, Li Y, Goldman M, Detre JA, O’Brien CP, Childress AR. Effects of varenicline on smoking cue-triggered neural and craving responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:516–526. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Matta SG, Gao W, Sharp BM. Local alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors in the nucleus accumbens modulate nicotine-stimulated dopamine secretion in vivo. Neuroscience. 2000;101:369–375. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Parker MC, See RE. Differential involvement of the core and shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens in conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:459–465. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1895-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rodriguez O, Pericot-Valverde I, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Ferrer-Garcia M, Secades-Villa R. Validation of smoking-related virtual environments for cue exposure therapy. Addict Behav. 2012;37:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JC, Wray JM, Hawk LW, Mahoney MC, Tiffany ST. Impact of varenicline on cue-specific craving assessed in the natural environment among treatment-seeking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;223:107–116. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2698-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon RA, Dukat M. Central nicotinic receptor ligands and pharmacophores. Pharm Acta Helv. 2000;74:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Clementi F. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:363–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabus SD, Martin BR, Brown SE, Damaj MI. Nicotine place preference in the mouse: influences of prior handling, dose and strain and attenuation by nicotinic receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:456–463. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grottick AJ, Trube G, Corrigall WA, Huwyler J, Malherbe P, Wyler R, Higgins GA. Evidence that nicotinic alpha (7) receptors are not involved in the hyperlocomotor and rewarding effects of nicotine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:1112–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillem K, Peoples LL. Varenicline effects on cocaine self administration and reinstatement behaviour. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:96–103. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328336e9c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson DM, Parkinson JA, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. The effects of nucleus accumbens core and shell lesions on intravenous heroin self-administration and the acquisition of drug-seeking behaviour under a second-order schedule of heroin reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;153:464–472. doi: 10.1007/s002130000635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Thun M, Yu XQ, Hartman AM, Cokkinides V, Center MM, Ross H, Ward EM. Changes in smoking prevalence among U.S. adults by state and region: estimates from the tobacco use supplement to the current population survey, 1992–2007. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:512. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones IW, Wonnacott S. Precise localization of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on glutamatergic axon terminals in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11244–11252. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3009-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JJ, Keller AB, Bowers BJ, Wehner JM. Performance of alpha7 nicotinic receptor null mutants is impaired in appetitive learning measured in a signaled nose poke task. Behav Brain Res. 2005;162:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled MA, Farid Araki K, Li B, Coen KM, Marinelli PW, Varga J, Gaal J, Le Foll B. The selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonist SB 277011-A, but not the partial agonist BP 897, blocks cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:181–190. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709991064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Chakraborty-Chatterjee M, Lev-Ran S, Barnes C, Pushparaj A, Gamaleddin I, Yan Y, Khaled M, Goldberg SR. Varenicline decreases nicotine self-administration and cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats when a long pretreatment time is used. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:1265–1274. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSage MG, Burroughs D, Dufek M, Keyler DE, Pentel PR. Reinstatement of nicotine self-administration in rats by presentation of nicotine-paired stimuli, but not nicotine priming. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Rezvani AH, Xiao Y, Slade S, Cauley M, Wells C, Hampton D, Petro A, Rose JE, Brown ML, Paige MA, McDowell BE, Kellar KJ. Sazetidine-A, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor desensitizing agent and partial agonist, reduces nicotine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:933–939. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Li Z, Pei L, Le AD, Liu F. The alpha7nACh-NMDA receptor complex is involved in cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2141–2147. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti ME, Lhuillier L, Kaupmann K, Markou A. Metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptors in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens shell are involved in behaviours relating to nicotine dependence. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9077–9085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1766-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippiello PM. Properties of putative nicotine receptors identified on cultured cortical neurons. Prog Brain Res. 1989;79:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Egger J, Kalb M. Smoking relapse: causes, prevention and recovery. Nova Science Publisher; New York: 2010. Contribution of drug cue, priming, and stress to reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in a rat model of relapse; pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Weiss F. Nitric oxide synthesis inhibition attenuates conditioned reinstatement of ethanol-seeking, but not the primary reinforcing effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1194–1199. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134219.93192.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Yee SK, Nobuta H, Poland RE, Pechnick RN. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour by drug-associated stimuli after extinction in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Yee SK, Nobuta H, Sved AF, Pechnick RN, Poland RE. Mecamylamine attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007a;32:710–718. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Palmatier MI, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Sved AF. Reinforcement enhancing effect of nicotine and its attenuation by nicotinic antagonists in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007b;194:463–473. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0863-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Palmatier MI, Donny EC, Sved AF. Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats: effect of bupropion, persistence over repeated tests, and its dependence on training dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Palmatier MI, Caggiula AR, Sved AF, Donny EC, Gharib M, Booth S. Naltrexone attenuation of conditioned but not primary reinforcement of nicotine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:589–598. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Jernigen C, Gharib M, Booth S, Caggiula AR, Sved AF. Effects of dopamine antagonists on drug cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:153–160. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328337be95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Paterson NE. The nicotinic antagonist methyllycaconitine has differential effects on nicotine self-administration and nicotine withdrawal in the rat. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:361–373. doi: 10.1080/14622200110073380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Burch JB, Collins AC. Effects of chronic nicotine infusion on tolerance development and nicotinic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;226:817–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R, Maurice T, Aujla H, Bowen WD, Weiss F. Differential effects of sigma1 receptor blockade on self-administration and conditioned reinstatement motivated by cocaine vs natural reward. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1967–1973. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Role LW. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:521–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar NS, Gotti C. Diversity of vertebrate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Picciotto MR. Genetics of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: relevance to nicotine addiction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Jr., Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Tidey J, Ray L. Effects of repeated days of smoking cue exposure on urge to smoke and physiological reactivity. Addict Behav. 2008;33:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JL, Beardsley PM. Effects of memantine, haloperidol, and cocaine on primary and conditioned reinforcement associated with cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:142–149. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM, Pedraza M, Abrams DB. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:133–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J. Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor EC, Parker D, Rollema H, Mead AN. The alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor partial agonist varenicline inhibits both nicotine self-administration following repeated dosing and reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakkanen JS, Jokitalo E, Tuominen RK. Up-regulation of beta2 and alpha7 subunit containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mouse striatum at cellular level. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2681–2691. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Justinova Z, Mascia P, Pistis M, Luchicchi A, Lecca S, Barnes C, Redhi GH, Adair J, Heishman SJ, Yasar S, Aliczki M, Haller J, Goldberg SR. Novel use of a lipid-lowering fibrate medication to prevent nicotine reward and relapse: preclinical findings. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1838–1847. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Thinschmidt JS. The correction of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor concentration-response relationships in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci Lett. 1998;256:163–166. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AB, Gilbert DG. Brain activity during anticipation of smoking-related and emotionally positive pictures in smokers and nonsmokers: a new measure of cue reactivity. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1627–1631. doi: 10.1080/14622200802412911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Froestl W, Markou A. Repeated administration of the GABAB receptor agonist CGP44532 decreased nicotine self-administration, and acute administration decreased cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:119–128. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Min W, Hackett A, Lowe D, Hanania T, Caldarone B, Ghavami A. The high-affinity nAChR partial agonists varenicline and sazetidine-A exhibit reinforcing properties in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly JR, Marks MJ, Gross SD, Collins AC. An autoradiographic analysis of cholinergic receptors in mouse brain after chronic nicotine treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258:1127–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechnick RN, Manalo CM, Lacayo LM, Vit JP, Bholat Y, Spivak I, Reyes KC, Farrokhi C. Acamprosate attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:222–227. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328345f72c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, Tolu S, Porcu E, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP, Maskos U, Fratta W. Crucial role of alpha4 and alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12318–12327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3918-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta D, Naylor CG, Barik J, Fernandes C, Wonnacott S, Stolerman IP. Drug discrimination and neurochemical studies in alpha7 null mutant mice: tests for the role of nicotinic alpha7 receptors in dopamine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Polonskaya Y, Gillespie A, Jakowec M, Lloyd GK, Langston JW. Localization of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey brain by in situ hybridization. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:58–69. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000911)425:1<58::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen BA, Perry DC. An autoradiographic analysis of [125I]alpha-bungarotoxin binding in rat brain after chronic nicotine exposure. Neurosci Lett. 2006;404:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Slade S, Wells C, Petro A, Lumeng L, Li TK, Xiao Y, Brown ML, Paige MA, McDowell BE, Rose JE, Kellar KJ, Levin ED. Effects of sazetidine-A, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor desensitizing agent on alcohol and nicotine self-administration in selectively bred alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;211:161–174. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1878-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE. Nicotine and nonnicotine factors in cigarette addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:274–285. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent PB. The diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:403–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilstrom B, Rawal N, Mameli-Engvall M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Dual effects of nicotine on dopamine neurons mediated by different nicotinic receptor subtypes. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Adamson LK, Grocki S, Corrigall WA. Reinstatement and spontaneous recovery of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130:396–403. doi: 10.1007/s002130050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Mason KM, Henningfield JE. Tobacco dependence treatments: review and prospectus. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:335–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib M. The cannabinoid antagonist AM251 attenuates nicotine self-administration and nicotine-seeking behaviour in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small E, Shah HP, Davenport JJ, Geier JE, Yavarovich KR, Yamada H, Sabarinath SN, Derendorf H, Pauly JR, Gold MS, Bruijnzeel AW. Tobacco smoke exposure induces nicotine dependence in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:143–158. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1716-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Chamberlain S, Bizarro L, Fernandes C, Schalkwyk L. The role of nicotinic receptor alpha 7 subunits in nicotine discrimination. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Lester HA. Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306:1029–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobey KM, Walentiny DM, Wiley JL, Carroll FI, Damaj MI, Azar MR, Koob GF, George O, Harris LS, Vann RE. Effects of the specific alpha4beta2 nAChR antagonist, 2-fluoro-3-(4-nitrophenyl) deschloroepibatidine, on nicotine reward-related behaviours in rats and mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;223:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2703-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C, Bovbjerg DH, Erblich J. Smoking-related videos for use in cue-induced craving paradigms. Addict Behav. 2007;32:3034–3044. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribollet E, Bertrand D, Raggenbass M. Role of neuronal nicotinic receptors in the transmission and processing of information in neurons of the central nervous system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner JM, Vardigan JD, Drott JM, Uebele VN, Renger JJ, Lee A, Li Z, Le AD, Hutson PH. T-type calcium channel antagonism decreases motivation for nicotine and blocks nicotine- and cue-induced reinstatement for a response previously reinforced with nicotine. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haaren F, Anderson KG, Haworth SC, Kem WR. GTS-21, a mixed nicotinic receptor agonist/antagonist, does not affect the nicotine cue. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:439–444. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieyra-Reyes P, Picciotto MR, Mineur YS. Voluntary oral nicotine intake in mice down-regulates GluR2 but does not modulate depression-like behaviours. Neurosci Lett. 2008;434:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Brown S, Changeux JP, Martin B, Damaj MI. The beta2 but not alpha7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is required for nicotine-conditioned place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:339–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SS, Epping-Jordan MP, Koob GF, Markou A. Blockade of nicotine self-administration with nicotinic antagonists in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62:743–751. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler MH, Weyers P, Mucha RF, Stippekohl B, Stark R, Pauli P. Conditioned cues for smoking elicit preparatory responses in healthy smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott S, Sidhpura N, Balfour DJ. Nicotine: from molecular mechanisms to behaviour. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott S, Barik J, Dickinson J, Jones IW. Nicotinic receptors modulate transmitter cross talk in the CNS: nicotinic modulation of transmitters. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30:137–140. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:1:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouda JA, Riga D, De Vries W, Stegeman M, van Mourik Y, Schetters D, Schoffelmeer AN, Pattij T, De Vries TJ. Varenicline attenuates cue-induced relapse to alcohol, but not nicotine seeking, while reducing inhibitory response control. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:267–277. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav. 2009;34:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Lena C, Picciotto MR, Changeux JP. Identification of four classes of brain nicotinic receptors using beta2 mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4461–4472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04461.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]