Abstract

Objective

To assess clinical success and safety of endoscopic pharyngoesophageal dilation after chemoradiation or radiation for head and neck cancer and to identify variables associated with dilation failure.

Study Design

Case series with chart review

Methods

Between 2000 and 2008 one hundred and eleven patients treated with chemoradiation or radiation for head and neck cancer with subsequent pharyngoesophageal stenosis requiring endoscopic dilation were identified. Patients were evaluated for endoscopic dilation technique, severity of stenosis, technical and clinical success and intra and post operative complications. The Diet/GT Score, range 1–5, was utilized to measure swallow success. Variables associated with dilation failure were analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression.

Results

271 dilations were analyzed, with 42 combined antegrade retrograde dilations, 208 dilations over a guidewire and 21 dilations without guidewire. Intraoperative patency and successful dilation of the stenotic segment was achieved in 95% of patients. A Diet/GT score of 5 (gastrostomy tube removed and soft/regular diet) was attained in 84/111 (76%) patients. Safety analysis showed complications occurred in 9% of all dilations. Perforations were noted in 4% of all procedures with only two esophageal perforations requiring significant intervention. Multiple dilations were associated with an increased risk for perforations. Further logistic regression analyses revealed that the number of dilations was indicating a poor outcome and low Diet/GT score.

Conclusion

Pharyngoesophageal stenosis, occurring after chemoradiation and radiation treatment, can be successfully and safely treated with endoscopic dilation techniques. Patients with restenosis, requiring multiple dilations, have a higher risk of persistent dysphagia.

Level of Evidence

2b individual retrospective cohort study

Keywords: esophageal stenosis, pharyngoesophageal stenosis, dysphagia, esophageal dilation, head and neck cancer, CARD

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and accounts for approximately 3% of all malignancies in the US.1,2 More than 90 % of HNC are squamous cell cancers.3 Survival for patients with advanced stage disease undergoing adjuvant or primary Chemoradiation (CRT) regimens has increased4–8 but is sometimes associated with late toxicities that may diminish the patient’s quality of life.9 Dysphagia, caused by partial or complete esophageal stenosis, is a particularly debilitating treatment consequence. The close proximity of mucous membranes in the pharyngoesophageal area make this site especially susceptible for stenosis formation.10 The healing process after radiation damage, involving fibrosis and scar tissue formation, can result in a concentric stricture.11 A recently published meta-analysis describes the risk for pharyngoesophageal stenosis in HNC with conventional radiation treatment (RT) to be 5.7% and notes a more than three fold increase, to 16.7%, with intensity modulated RT in combination with chemotherapy.12,13

Most patients have partial stenoses that are amenable to standard antegrade esophageal dilation techniques with low rates of esophageal perforation. Dilation of complete esophageal stenosis is more technically challenging but can be successfully achieved through a combined antegrade and retrograde endoscopic dilation (CARD) technique.14

The aim of this retrospective study is to assess success rates and safety of endoscopic esophageal dilation in HNC patients who have undergone CRT or RT. Additionally we aim to identify variables associated with poor outcome after esophageal dilation.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on HNC patients that underwent antegrade or CARD pharyngoesophageal dilation between January 2000 and December 2008. Patients were identified by searching the database for all patients that underwent esophageal dilation after CRT or RT for HNC at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Treatment regimens included primary concurrent or sequential CRT/RT, and primary surgery with adjuvant CRT/RT. The study population consisted of patients with primary tumors in the oral cavity, orophaynx, hypopharynx, larynx, nasopharynx and unknown primaries. All patients had a minimum follow up of 12 months after the initial dilation. Patients with thyroid tumors or primaries outside the head and neck area, such as lung cancers or esophageal cancers, or with recurrence in the stenotic segment were excluded. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board.

Pharyngoesophageal strictures

Prior to endoscopic esophageal dilation, dysphagia assessment with a video swallowing study was undertaken in most patients. Stricture location was categorized as: cricopharyngeal, esophageal, or pharyngeal. Stricture severity was endoscopically gauged by the size of the stenotic segment: complete stenosis; partial stenosis ≤ 5mm; and partial stenosis > 5mm.

Dysphagia assessment pre and post dilation

Dysphagia assessment included diet consistency and gastrostomy tube (GT) status pre dilation and one, three, six and 12 months post dilation. Prior to RT or CRT all patients were recommended to undergo GT placement. Diet was described in five categories: NPO, liquid, pureed, soft or regular diet. As a measurement for success of dilation, the Diet/GT Scale was utilized.15 The five level scoring system, combines GT status and diet: Score 1, GT present and NPO; Score 2, GT present and liquid pureed/diet; Score 3, GT present and soft/regular diet; Score 4, no GT and liquid/pureed diet; Score 5, no GT and soft/regular diet.

Endoscopic dilation procedures

Patients with complete pharyngoesophageal stenosis underwent CARD via a technique previously described by Goguen et al.14 Patients with partial stenosis, whereby a guidewire could be passed through the stenotic segment, underwent antegrade dilation using a guidewire and progressively larger dilators (Savory-Gilliard guidewire, Cook Endoscopy, Winton-Salem, NC). Alternatively, a smaller subset of patients with partial stenosis underwent antegrade dilation without a guidewire. Dilation technique was at the discretion of the surgeon. Repeat dilations were performed based on the patient’s dysphagia symptoms. Shortly after dilation patients followed up with their swallow therapist to establish a safe oral diet and to continue swallow therapy.

Statistics

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate possible variables associated with dilation failure and with perforation. Factors included in the analyses were clinical and treatment factors, including age, gender, size of stenosis, T-and N-stage, type of treatment, pre dilation diet, complications, time of dilation and number of dilations. Post dilation Diet/GT Score of 1, 2 or 3 was considered a poor outcome and defined as dilation failure. The Wald Chi-square test from the logistic regression model was used to test for statistical significance. Variables with p values <0.25 were considered for model building of the multivariate analyses. A 2-sided p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Time from dilation to GT removal was analyzed using the method of Kaplan and Meier. SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

One hundred and eleven patients met inclusion criteria for this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Factors | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 78 | 70.3% |

| Female | 33 | 29.7% |

| Age | ||

| Median, range | 57.7, 39–84 | |

| Primary Tumor Site | ||

| Oropharynx | 55 | 49.6% |

| Hypopharynx | 8 | 7.2% |

| Larynx | 15 | 13.5% |

| Oral Cavity | 8 | 7.2% |

| Nasopharynx | 10 | 9.0% |

| Unknown Primary | 15 | 13.5% |

| T-stage | ||

| T0 | 15 | 13.5% |

| T1 | 30 | 27.0% |

| T2 | 31 | 27.9% |

| T3 | 25 | 22.5% |

| T4 | 10 | 9.0% |

| N-stage | ||

| N0 | 20 | 18.0% |

| N1 | 18 | 16.2% |

| N2 | 58 | 48.6% |

| N3 | 15 | 13.5% |

| Overall Stage | ||

| 1 | 2 | 1.8% |

| 2 | 9 | 8.1% |

| 3 | 25 | 22.5% |

| 4 | 75 | 67.6% |

| Treatment | ||

| Primary CRT/RT | 99 | 89.2% |

| Primary Surgery; post CRT/RT | 12 | 10.8% |

| Post CRT ND | ||

| No | 76 | 68.5% |

| Yes | 35 | 31.5% |

| Size of Stenosis | ||

| ≤ 5mm | 21 | 18.9% |

| > 5mm | 68 | 61.3% |

| Complete | 22 | 19.8% |

Evaluation of swallowing function

The median time from completion of CRT/RT to first dilation was 5.9 months (range 2.3–99.6 months). The majority of patients, 95/111 (86%), had a videofluoroscopy done prior to first dilation, which demonstrated partial or complete stenosis in 91% (86/95) patients. Videofluoroscopy showed further swallowing impairment, mostly oropharyngeal dysphagia, in 72% of those patients. At the time of dilation, 92/111 (83%) patients were GT dependent, and 19/111 (17%) patients had their GTs removed. Patients swallowing function was further evaluated according to dietary intake pre dilation (Table 2). Thirty three percent, (37/111) patients, were unable to take any oral diet, 21% (25/111) took an oral diet with soft or regular food.

Table 2.

Diet Assessment

| Diet | Pre dilation # of patients (%) | 1 month post dilation # of patients (%) | 3 months post dilation # of patients (%) | 6 months post dilation # of patients (%) | 12 months post dilation, # of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT | Yes | 92 (83%) | 79 (71%) | 49 (44%) | 30 (27%) | 24 (22%) |

| No | 19 (17%) | 32 (29%) | 62 (56%) | 81 (73%) | 87 (78%) | |

| Diet | NPO | 37 (33%) | 11 (10%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (5%) | 7 (6%) |

| Liquid | 18 (16%) | 8 (8%) | 4 (4%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | |

| Pureed | 30 (27%) | 27 (24%) | 20 (18%) | 11 (10%) | 7 (6%) | |

| Soft | 24 (22%) | 38 (34%) | 34 (30%) | 26 (23%) | 18 (16%) | |

| Regular | 1 (1%) | 26 (23%) | 48 (43%) | 68 (61%) | 77 (70%) | |

| NA | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | |

| Diet/GT Score | 1 | 37 (33%) | 11 (10%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 7 (6%) |

| 2 | 43 (39%) | 31 (28%) | 21 (19%) | 9 (8%) | 7 (6%) | |

| 3 | 12 (11%) | 37 (33%) | 23 (20%) | 15 (14%) | 10 (9%) | |

| 4 | 5 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | |

| 5 | 13 (12%) | 27 (24%) | 59 (53%) | 79 (71%) | 84 (76%) | |

| NA | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

GT- Gastrostomy tube, NPO- nil per mouth, NA- not available

Pharyngoesophageal stenosis

Stenoses were found in most patients at the cricopharyngeal or upper cervical esophageal regions, 109/111 (98%). Only 2 patients had stenosis in other areas of pharynx including base of tongue and hypopharynx. Three patients had longer stenosis extending over multi regions from hypopharynx to cervical esophagus. Partial stenosis with lumen >5mm was found in 61% patients, ≤5mm stenosis in 18% and complete stenosis in 21% of patients at time of first dilation. A total of 271 dilations were performed. Repeat dilations were needed in 65/111 (59%) patients (Table 3). On average, each patient underwent 2.4 dilations, and the median number of dilations per patient was 2.

Table 3.

Dilations

| No. of dilations | |

|---|---|

| Total No. of dilations | 271 |

| Dilation technique | |

| Guidewire dilation | 208 |

| Dilation without guidewire | 21 |

| Ante-retrograde dilation | 42 |

| No. of dilations within 1st year | No. of patients |

| 1 | 57 |

| 2 | 32 |

| 3 | 11 |

| 4–8 | 11 |

Dilation techniques

Three different dilation techniques were recorded during the observation period (Table 3). Dilation over a guidewire was the most common technique in patients with partial stenosis. Some patients (11 patients), with minor partial stenosis, underwent dilations without a guidewire (21 dilations). The size of partial stenosis ranged from 3–14mm before the first dilation, and antegrade dilation achieved a lumen between 12–20mm in these patients. Twenty-two patients with complete esophageal stenosis underwent CARD. Successful CARD dilations, in patients with complete stenosis, achieved a lumen between 10–20mm.

Success of endoscopic esophageal dilation

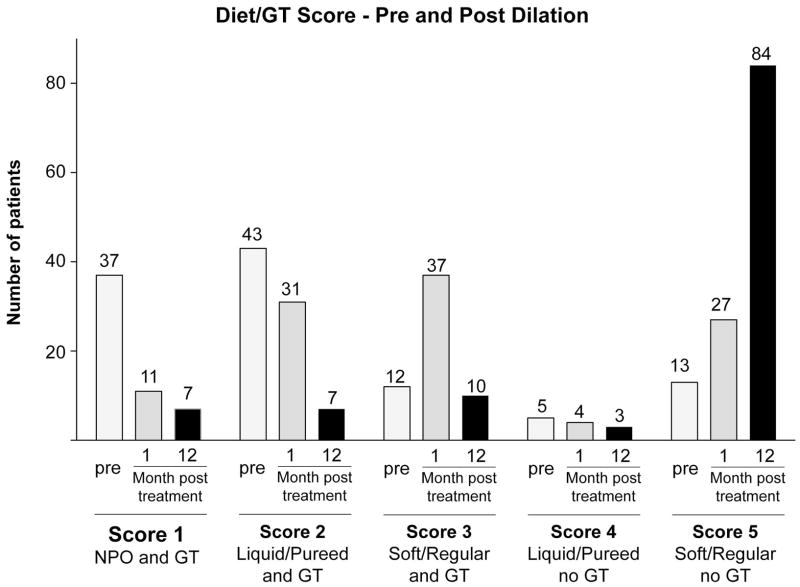

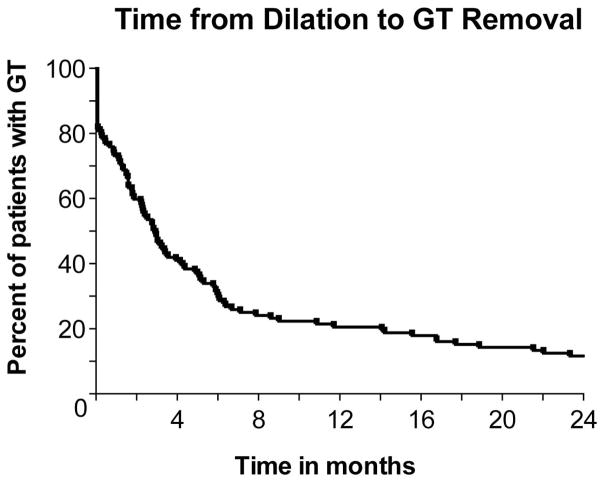

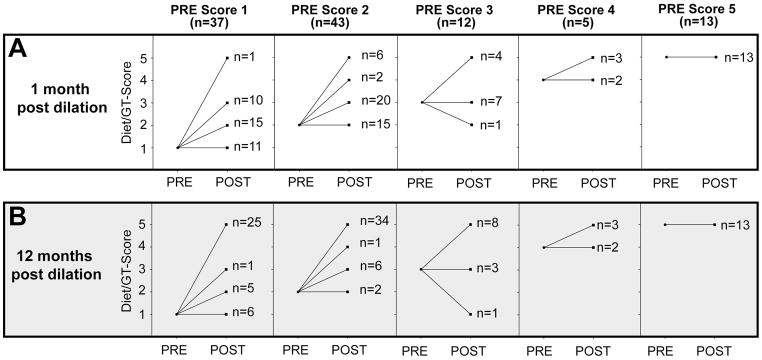

Success of the endoscopic dilation was assessed by the following measures: the ability to achieve intraoperative pharyngoesophageal patency and dilation of the stenotic segment, oral diet, GT dependence and Diet/GT Score at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months post dilation (Table 2). In 106/111 (95%) patients, the initial dilation accomplished intraoperative patency and the stenotic segment was dilated. Median Diet/GT Score pre dilation was 2 (GT dependent with liquid/pureed diet) and patients showed improved median Diet/GT Score of 3 (GT dependent with soft/regular diet) at one month and of 5 (GT independent with soft/regular diet) at 12 months after dilation (Figure 1). One month after dilation biggest improvement in swallowing function was observed in patients with initial Diet/GT Score of 1 and 2 whose Diet/GT Scores increased in 70% (26/37) and 65% (28/43) respectively (Figure 2). One year after dilation 104/111 (94%) achieved an oral diet and the GT was removed in 87/111 (78%) patients (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Diet/GT Score pre and post dilation.

Diet/GT Score pre dilation and 1 month and 12 months post dilation.

Figure 2. Change in Diet/GT Score.

Visualization of change in Diet/GT Score at 1 month post dilation (A) and 12 months post dilation (B) compared to pre dilation score.

Figure 3. GT dependence after dilation.

GT removal rate within 24 months following dilation.

Additional swallow recovery was noted after the one year post dilation observation period. Further assessment at 24 months revealed that 98/111 patients (88%) had their GTs removed.

Patients with persistently poor swallowing function

Seven of 111 (6%) patients remained GT dependent and NPO at one year post dilation. This group had diverse patient characteristics (Table 4): 4/7 patients had complete stenosis requiring CARD and in 1/4 intraoperative pharyngoesophageal patency was not attained. Six of seven patients had between 2 and 8 repeat dilations. Two patients were able to become GT independent at a later time point between 18 and 24 months.

Table 4.

Patients with persistently poor swallowing function

| Patient | Primary | TNM stage | Treatment | No. of dilations | Complication post dilation | Diet/GT Score pre dilation | Diet/GT Score 1 year post dilation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oroph | T2N3 | CRT + post CRT ND | 5 | yes | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Oroph | T2N2a | CRT + post CRT ND | 8 | No | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Oroph | T1N2a | CRT | 5 | No | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Larynx | T4N0 | CRT | 8 | No | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | Larynx | T4N0 | Surgery + post op CRT | 3 | No | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | Hypoph | T3N0 | CRT | 1 | No | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | Nasoph | T2N2 | CRT | 2 | Yes | 1 | 1 |

Complications after endoscopic esophageal dilation

There were no deaths associated with the dilation procedures. The complication rate per dilation procedure was 9% (25/271) and included: 8/208 (4%) in antegrade guidewire dilations; 1/21 (5%) in dilations without guidewire and 16/42 (38%) CARD (Table 5). Complications requiring significant intervention were 4/271 (1.4%).

Table 5.

Complications

| Complication | No dilations (%) | Type of dilation | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| All Complications in 22 patients | 25/271 (9%) |

CARD 16 GW 8 B 1 |

|

|

| |||

| Increased length of hospital | 18/271 (6%) |

CARD 13 GW 5 |

|

|

| |||

| All Perforations | 11/271 (4%) |

CARD 7 GW 4 |

|

| Microperforations with no interventions | 7/271 (2.5%) | CARD 6 GW 1 |

7 patients i.v. Antibiotics, observation, serial CXR, 1 patient GT placement |

| Perforation requiring minor intervention (Pneumothorax and Pharyngocutaenous fistula) | 3/271 (1%) | CARD 1 GW 2 |

1 patient chest tube placement and Poly flex stent, 2 patients i.v. Antibiotics and wound packing |

| Perforation leading to significant adverse event Epidural abscess | 1/271 (0.4%) | GW 1 | 1 patient with spinal canal decompression |

|

| |||

| All GT site complications | 8/271 (3%) | CARD 8 | |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 5/271 (1.8%) | 5 patients with observation | |

| GT lost/replaced | 1/271 (0.4%) | 1 patient GT replaced at bedside | |

| Extravasation at GT site | 1/271 (0.4%) | 1 patient GT replaced in OR | |

| Abdominal wall cellulitis | 1/271 (0.4%) | 1 patient i.v. Antibiotics and observation | |

|

| |||

| Minor infections thrush, mucositis, cellulitis | 5/271 (1.8%) |

CARD 1 GW 3 B 1 |

2 patients Antimykotikum, 1 patient i.v. Antibiotics, 1 patient Salivary bypass tube removed and iv Antibiotics |

|

| |||

| Other medical, respiratory failure, intraoperative hypotension, diarrhea | 3/271 (1%) |

CARD 2 GW 1 |

1 patient requiring intubation, 1 patient with observation, 1 patient p.o. Antibiotics, |

GT- gastrostomy tube, CARD- combined ante-retrograde dilation, GW- guidewire, B-bougie dilator

Perforation was the most common complication encountered in 11/271(4%) dilations, whereby 7/42 (16%) perforations occurred in CARD and 4/208 (2%) perforations in antegrade guidewire dilations. These perforations were mostly microperforations, 7/271 (2.5%), and resulted in pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum or subcutaneous emphysema in the neck appreciated on post procedure chest radiograph. Patients were treated with intravenous antibiotics, observed in the hospital, and followed with serial chest radiographs. No further intervention was required for those patients with microperforations.

A perforation requiring more intervention occurred in four patients. Two patients, who underwent guidewire dilation developed pharyngocutaneous fistulas that resolved with intravenous antibiotics and wound packing. Chest tube placement and temporary pharyngeal stent for treatment of pneumothorax and pharyngeal tear, was necessary in one CARD patient. Additionally, one patient developed an epidural abscess after antegrade guidewire dilation that required spinal canal decompression This patient recovered completely following a prolonged 34-day hospital stay, and was able to tolerate a soft diet but remained GT dependent throughout the follow up period.

Univariate logistic regression analyses for risk factors of perforations were performed. Variables included were T-stage, N-stage, Overall stage, treatment and number of dilations. A higher number of dilations was associated with an increased risk of perforation (p=0.004, OR=1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.3).

Among patients receiving CARD, GT site complications were found in 8/42 (19%) dilations. These included pneumoperitoneum and leakage around the GT site. Almost all of those patients were treated conservatively with observation and serial chest or abdominal radiographs with successful resolution of pneumoperitoneum. Exchange of GT in the operating room was only necessary for one patient.

Although the vast majority of complications did not require a return to the operating room, an increased length of hospital stay, was seen in 18/25 (72%) of the procedures with complications. Assessment of diet and GT status after a complicated dilation procedure showed that 17/22 patients had their GT removed and were able to eat a soft or regular diet.

Analysis of Factors Affecting Successful Dilation

Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to look for associations with poor outcome after dilation (Table 6). A low Diet/GT Score, group 1–3, at one year after initial dilation was used to define patients with a poor dilation outcome. Results indicated that an increasing number of dilations during the first year was strongly associated with a poor outcome. Patients with higher T-stage had a tendency to perform worse, as well as patients where the initial dilation procedure was performed 6 months after the end of CRT, but both factors did not reach statistical significance. The extent of stenosis, considering complete stenosis involving CARD dilation, versus partial stenosis, was not associated with worse outcome.

Table 6.

Univariate Logistic Regression Results

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | 2.3 | (0.9, 5.8) | 0.08 |

| Complete Stenosis (yes vs. no) | 2.4 | (0.9, 6.7) | 0.09 |

| T-stage (ordinal) | 1.4 | (0.97, 2.12) | 0.07 |

| N-stage (ordinal: N0, N1, N2, N3) | 0.8 | (0.5, 1.3) | 0.42 |

| Overall Stage (ordinal) | 0.9 | (0.5, 1.7) | 0.76 |

| Post CRT Neck Dissection (yes vs. no) | 1.0 | (0.4, 2.7) | 0.95 |

| Treatment (Primary surgery vs. CRT/RT) | 0.6 | (0.1, 3.2) | 0.61 |

| Pre-Dilation Diet (NPO vs. other) | 2.1 | (0.8, 5.3) | 0.12 |

| Time (> 6 months vs. ≤ 6 months) | 2.4 | (0.9, 5.9) | 0.07 |

| Complications (yes vs. no) | 1.9 | (0.6, 6.2) | 0.29 |

| # Dilations in 1st Year (continuous) | 1.6 | (1.1, 2.1) | 0.005 |

| Age at Diagnosis (continuous) | 1.02 | (0.97, 1.06) | 0.50 |

The outcome for these models is having a GT/Diet Score of 1, 2, or 3.

In the multivariate model, after controlling for sex, T-stage, time of dilation, pre dilation diet and complete versus partial stenosis, number of dilations remained statistically significant (p=0.04, OR=1.5, 95% CI 1.02–2.09).

Discussion

Pharyngoesophageal strictures are a frequent problem encountered in patients with HNC treated with combined modality therapy. Partial stenosis develops in 9–21%11,16,17 and complete stenosis in 0.8–4%.10,13 Endoscopic therapy, with antegrade or ante-retrograde esophageal dilations, is an established treatment to alleviate pharyngeal or esophageal stenosis post HNC treatment. However, only few studies have looked at management and outcome of endoscopic dilations in this patient group.14,18,19 The purpose of this study was to assess success and safety of dilation procedures in HNC patients post treatment. We identified 111 patients who underwent 271 endoscopic esophageal dilations following HNC treatment making this one of the largest and most detailed studies in the literature.

Our results show that technical success, as seen by achieving intra-operative esophageal patency and dilating the stenosis was successful in 95%. Similar results were found by Dhir et al,19 who attained esophageal patency in 20/21 patients dilated with antegrade guidewire technique. Another case series by Ahlawat et al.20 reported technical success in 80% of patients, also treated with antegrade guidewire dilations.

The measures for functional success of dilations in our study were GT status, diet and the Diet/GT Score. Other dysphagia scales used in HNC patients are the Swallowing Performance Status Scale (SPSS)21 or the functional oral intake scale (FOIS).22 The SPSS requires a videofluoroscopy for assessment that was not available for all of our patients post dilation. The FOIS was validated in stroke patients and only recently applied to HNC patients by Kotz et al.23 in a prospective randomized trial. In the retrospective setting of this study we chose the Diet/GT Score because it combines the two objective criteria diet and GT status and was previously applied to HNC patients successfully from our group. 15

Small patient numbers in other case series and diverse approaches for reporting dilation success make a comprehensive comparison of our results challenging. An improvement from median pre-dilation Diet GT Score of 2 to median score of 3 was observed 1 month after dilation. Successful removal of GT was found in 78% after one year and 88% after two years. Dhir et al.19 used a dysphagia scale and reported adequate dysphagia relief in 75% patients. These patients had either no dysphagia or occasional dysphagia to solids 4–36 weeks post procedure. The same dysphagia scale was used by Ahlawat et al.,20 reporting 84% adequate dysphagia relief. GT status was not reported in these studies. Other smaller case series on CARD dilations stated improvement in oral intake in 6/7 patients.24

The majority of our patients achieved intra-operative esophageal patency, yet a significant number, 49% (54/111), required repeat dilations. This is consistent with other clinical studies demonstrating the need for multiple dilations.18,20,24,25 Case series reports, using antegrade dilation technique, identified the need for multiple dilations in 74%,26 58%20 and 33%.19 For patients undergoing an initial CARD dilation, Fowlkes et al.18 reported an average need of 7 anterograde dilations following the initial CARD procedure. Comparing this data to our case series, repeated antegrade dilations were required in most CARD patients with an average of 3 dilations following CARD.

Beyond the technical success, many other factors influence swallowing post dilation. As seen on pre dilation video swallow, 72% of our patients additionally had oropharyngeal phase swallow dysfunction. This is the result of tissue edema, deformed anatomy and immobility of the larynx and cricoid due to post radiation changes.20,27,28 All of our study patients participated in post CRT swallow therapy as a crucial part of their treatment. Specific swallowing exercises directed towards structures impaired during and after CRT have been shown to improve swallowing outcome. 23,29–31 Therefore we believe not all swallowing improvement noted in the observation period, especially at long term follow up, can be attributed to the dilation procedures. Rather multiple factors contribute to swallowing recovery, including: dilation procedures, swallow therapy, and post radiation tissue recovery over time.

Our overall complication rate was low at 9% for a total of 271 dilations demonstrating that phayrngoesophageal dilations are relatively safe. The most common complications were perforations (4%) which occured usually as microperforations and resolved spontaneously. A case series by Hernandez et al.32 reported a similar rate of 3.9% for anterograde dilations. Higher perforation rates between 17%–25% were noticed for CARD dilations. 27,33 Unique to CARD were GT site complications observed in 19% of our CARD procedures which were managed successfully with observation in the majority of cases. In other smaller case series, GT complications were seen in 12%.18,33 Dilation of the GT site to permit retrograde passage of flexible gastroscope is the main factor contributing to these complications. In general our large patient series revealed mainly minor complications but there remains a risk for serious complications, particularly related to pharyngoesophageal perforations, and diligent postoperative care is needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study shows that anterograde and combined ante-retrograde dilation techniques are not only a safe but also a very successful treatment method for HNC patients with pharyngoesophageal strictures after CRT and RT treatment. The number of dilations within the first year was associated with persistent dysphagia and a risk for perforation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None

Oral presentation, Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting, January 24–26, 2013 in Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S.A.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:

- Salary for Anna Snavely, PhD was supported by NIH grant (2 T32 CA 9337-31)

- none of the authors has any financial interests

- no other financial disclosures

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haddad RI, Shin DM. Recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1143–1154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Licitra L, Felip E. Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20 (Suppl 4):121–122. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorch JH, Goloubeva O, Haddad RI, et al. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or in combination with docetaxel in locally advanced squamous-cell cancer of the head and neck: long-term results of the TAX 324 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:153–159. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Posner MR, Hershock DM, Blajman CR, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1705–1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:92–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terrell JE, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, et al. Clinical predictors of quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:401–408. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurell G, Kraepelien T, Mavroidis P, et al. Stricture of the proximal esophagus in head and neck carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003;97:1693–1700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee WT, Akst LM, Adelstein DJ, et al. Risk factors for hypopharyngeal/upper esophageal stricture formation after concurrent chemoradiation. Head Neck. 2006;28:808–812. doi: 10.1002/hed.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JJ, Goldsmith TA, Holman AS, Cianchetti M, Chan AW. Pharyngoesophageal stricture after treatment for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2012;34:967–973. doi: 10.1002/hed.21842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawson JD, Otto K, Grist W, Johnstone PA. Frequency of esophageal stenosis after simultaneous modulated accelerated radiation therapy and chemotherapy for head and neck cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goguen LA, Norris CM, Jaklitsch MT, et al. Combined antegrade and retrograde esophageal dilation for head and neck cancer-related complete esophageal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:261–266. doi: 10.1002/lary.20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapuy CI, Annino DJ, Snavely A, et al. Swallowing function following postchemoradiotherapy neck dissection: review of findings and analysis of contributing factors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:428–434. doi: 10.1177/0194599811403075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best SR, Ha PK, Blanco RG, et al. Factors associated with pharyngoesophageal stricture in patients treated with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2011;33:1727–1734. doi: 10.1002/hed.21657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caglar HB, Tishler RB, Othus M, et al. Dose to larynx predicts for swallowing complications after intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1110–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowlkes J, Zald PB, Andersen P. Management of complete esophageal stricture after treatment of head and neck cancer using combined anterograde retrograde esophageal dilation. Head Neck. 2012;34:821–825. doi: 10.1002/hed.21826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhir V, Vege SS, Mohandas KM, Desai DC. Dilation of proximal esophageal strictures following therapy for head and neck cancer: experience with Savary Gilliard dilators. J Surg Oncol. 1996;63:187–190. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199611)63:3<187::AID-JSO10>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahlawat SK, Al-Kawas FH. Endoscopic management of upper esophageal strictures after treatment of head and neck malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnell MP, MacCracken E. A Database Information Storage and Reporting System for Videofluorographic Oropharyngeal Motility (OPM) Swallowing Evaluations. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1994;3:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crary MA, Mann GD, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1516–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotz T, Federman AD, Kao J, et al. Prophylactic swallowing exercises in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiation: a randomized trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:376–382. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steele NP, Tokayer A, Smith RV. Retrograde endoscopic balloon dilation of chemotherapy- and radiation-induced esophageal stenosis under direct visualization. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007;28:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dellon ES, Cullen NR, Madanick RD, et al. Outcomes of a combined antegrade and retrograde approach for dilatation of radiation-induced esophageal strictures (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1122–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuna Y, Kocak E, Dincer D, Koklu S. Factors affecting the success of endoscopic bougia dilatation of radiation-induced esophageal stricture. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:424–428. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1875-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maple JT, Petersen BT, Baron TH, Kasperbauer JL, Wong Kee Song LM, Larson MV. Endoscopic management of radiation-induced complete upper esophageal obstruction with an antegrade-retrograde rendezvous technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kronenberger MB, Meyers AD. Dysphagia following head and neck cancer surgery. Dysphagia. 1994;9:236–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00301917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Y, Shen Q, Wang Y, Lu K, Wang Y, Peng Y. A randomized prospective study of rehabilitation therapy in the treatment of radiation-induced dysphagia and trismus. Strahlenther Onkol. 2011;187:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s00066-010-2151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarus C, Logemann JA, Song CW, Rademaker AW, Kahrilas PJ. Effects of voluntary maneuvers on tongue base function for swallowing. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2002;54:171–176. doi: 10.1159/000063192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pauloski BR. Rehabilitation of dysphagia following head and neck cancer. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008;19:889–928. x. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez LV, Jacobson JW, Harris MS. Comparison among the perforation rates of Maloney, balloon, and savary dilation of esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:460–462. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan CA, Jaklitsch MT, Haddad R, et al. Endoscopic management of hypopharyngeal stenosis after organ sparing therapy for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1924–1931. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000147921.74110.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]