Abstract

The cryptic thioesterase LovG is found to be responsible for product release from the lovastatin nonaketide synthase (LNKS or LovB). The same enzyme also helps improving turnover of LovB through hydrolysis of incorrectly tailored intermediates.

Keywords: Lovastatin, Biosynthesis, Polyketide Synthase, Product Release, Thioesterase

Lovastatin, a polyketide produced by the fungus Aspergillus terreus[1], is one of the most important natural products discovered to date. Both lovastatin and the semi-synthetic derivative simvastatin are widely prescribed hypercholesterolemia drugs because of their inhibitory activities towards 3S-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR).[2] The fermentative production of lovastatin has therefore been one of highest grossing processes involving a natural product. We recently developed a biocatalytic process of converting an intermediate of the lovastatin biosynthetic pathway, monacolin J acid (3) into simvastatin acid (5) in a single enzymatic step.[3] Therefore, having a fast-growing heterologous host, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, that can produce 3 directly without the need to purify lovastatin followed by side chain hydrolysis, is an attractive process option. To do so, identification of a complete biosynthesis pathway leading to 3 is required.

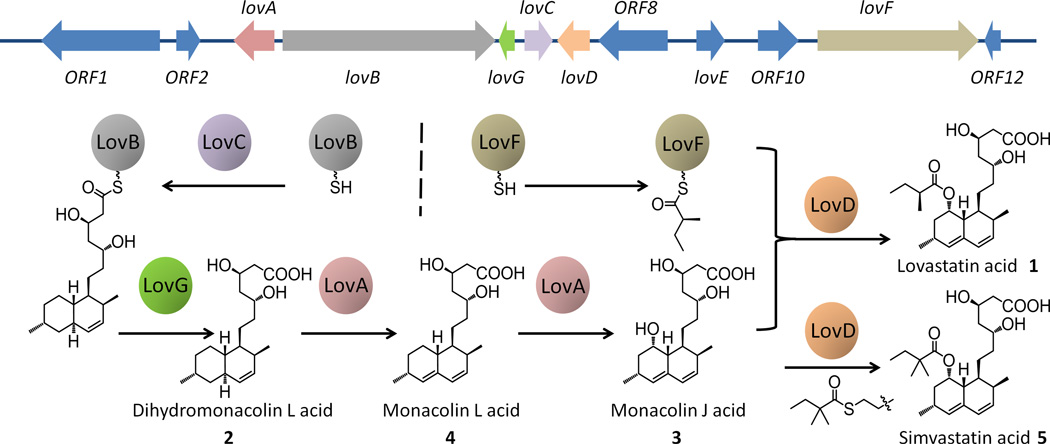

The biosynthetic gene cluster for lovastatin acid (1) in A. terreus was first identified in a pioneering work by Kennedy et al.[4] Through genetic[4–5] and biochemical[6] characterizations, it is now known that two highly reducing iterative type I polyketide synthases (HR-PKSs) play central roles in biosynthesis of 1. The lovastatin nonaketide synthase (LNKS or LovB), together with the dissociated enoylreductase LovC, are responsible for the programmed assembly of dihydromonacolin L acid (2).[4] 2 is then modified by the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase LovA via hydroxylation and dehydration to afford monacolin L acid (4). The same enzyme also catalyzes hydroxylation at C-8 of 4 to produce 3.[6c] Lastly, the α-methylbutyryl side chain is synthesized by lovastatin diketide synthase (LDKS or LovF) and is transferred to the C-8 hydroxyl group of 3 by the acyl transferase LovD to yield 1 (Figure 1).[6a] It is the function of LovD that was exploited for the enzymatic synthesis of simvastatin.[7]

Figure 1.

Lovastatin biosynthetic gene cluster and pathway.

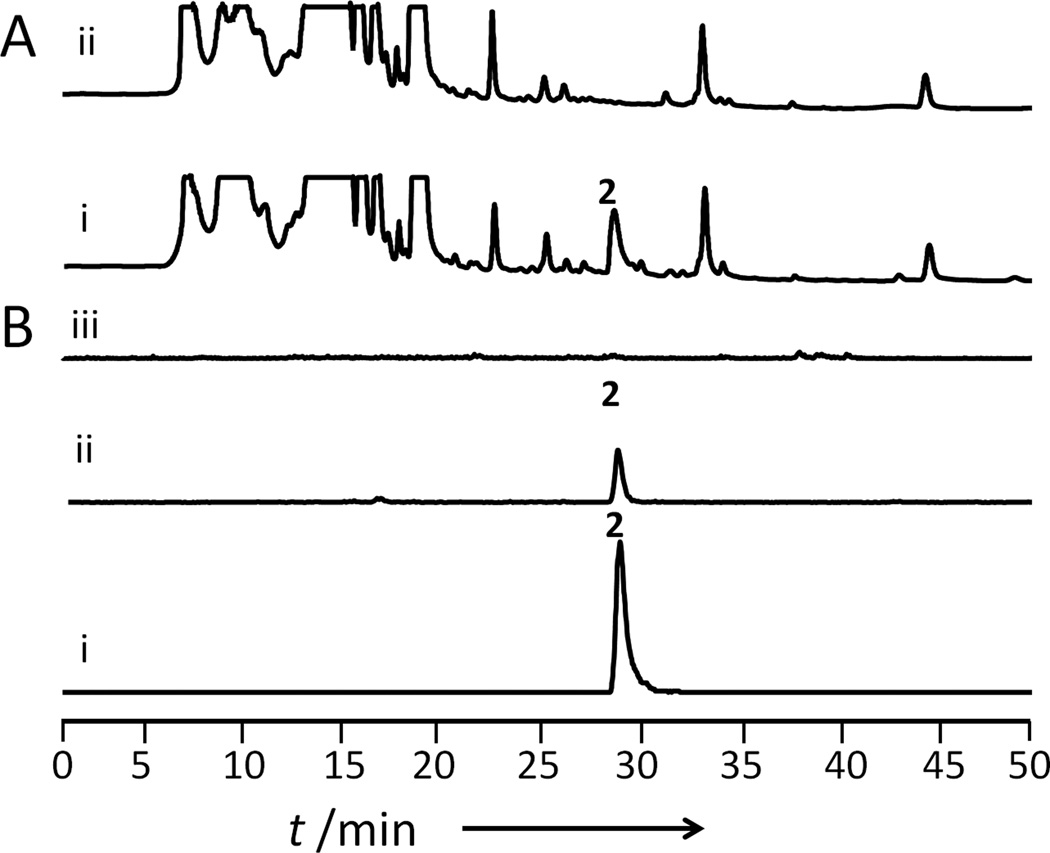

Notwithstanding these insights into the lov pathway, one unsolved biochemical step is the release of 2 from LovB that allows multiple turnover by this enzyme. In our previous in vitro reconstitution work, we showed that purified LovB and LovC were sufficient to assemble 2 tethered to LovB from malonyl-CoA, but were not able to release the product.[6b] To test whether this is also the case in S. cerevisiae, LovB and LovC were coexpressed in S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA, which is a vacuolar protease-deficient yeast strain harbouring an A. nidulans phosphopantethienyl transferase npgA.[8] Following extraction of the 3-day yeast culture, no trace of 2 was found by selective ion monitoring (Figure 3A and Figure S1B), confirming the lack of a releasing function with LovB and LovC only. Serendipitously in our in vitro work, we identified non-native thioesterase (TE) domains from unrelated fungal PKSs that can offload 2.[6b] Co-expression of fungal TE domains, such as the PKS13 TE,[9] Hpm3 TE,[10] etc, with LovB and LovC resulted in detectable levels of 2 from BJ5464-NpgA, albeit with very low titers (< 400 µg/L, Figure S2). Given the known expression levels of LovB (~4 mg/L),[6b] this low titer corresponds to an average turnover of less than 90 for LovB. These studies strongly indicate that 1) the low titer of 2 from S. cerevisiae must be overcome by increasing the turnover rate of LovB; and 2) there must exist a natural TE that partners with LovB in the release of 2.

Figure 3.

LovG releases 2 from LovB. A) HPLC chromatogram at 200 nm of fermentation extracts from 3-day cultures of BJ5464-NpgA expressing i) LovB, LovC and LovG; ii) LovB and LovC; and B) Extracted ion chromatograms of m/z [M−H]− 323 corresponding to 2 in in vitro experiments containing i) LovB, LovC and LovG; ii) LovB and LovC, treated with 1M KOH; iii) LovB and LovC with no 1M KOH treatment. All enzymes are added to a final concentration of 10 µM. The reactions were performed at 25°C for 12 hours.

To identify the TE that is involved in the biosynthesis of 2, we revisited the A. terreus lov gene cluster and searched for a likely candidate. The only known TE-like enzyme in the gene cluster, LovD, is highly specific towards LovF and does not function with LovB. A thorough bioinformatic analysis of genes of unassigned function suggests that a gene (ATEG_09962) that is located between lovB and lovC (Figure 1) warrants further scrutiny. This gene was initially assigned as orf5[4] and later as lovG[11], with an annotation of the protein product as either a hypothetical protein or an oxidoreductase. Conserved domain analysis of LovG indicates that LovG in fact belongs to the esterase-lipase family of serine hydrolases (Figure S3). Notably, close homologs of LovG are also found in related biosynthetic pathways, including MlcF in the compactin pathway in Penicillium citrinum[12] (58% identity, 71% similarity); and MokD in the monacolin K (lovastatin) pathway in Monascus pilosus[13] (67% identity, 76% similarity). As is the case for lovG, both mlcF and mokD are located between the genes encoding nonaketide PKS and the trans-acting enoylreductase. RT-PCR analysis showed that mlcF and mokD are moderately co-transcribed with the other biosynthetic genes in their corresponding clusters, which suggests that these enzymes should be involved in the biosynthetic pathways.[12–13] Therefore, we hypothesized that LovG is the missing link that is required for LovB turnover and release of 2.

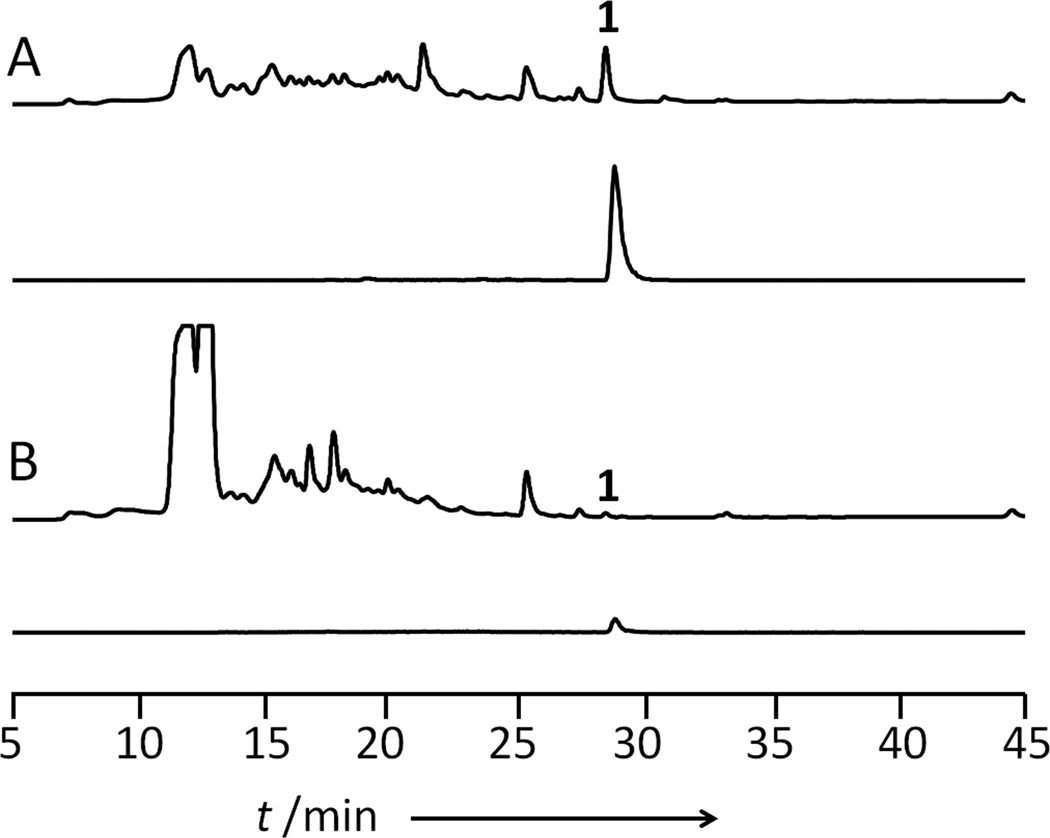

We first determined the role of lovG in biosynthesis of 1 in A. terreus. A genetic disruption of lovG was performed using a double-crossover recombination with the zeocin-resistant marker, followed by identification of desired ΔlovG mutants via diagnostic PCR (Figure S4). Metabolite analysis of the ΔlovG mutants showed dramatically reduced level of 1 (< 5%) compared to the wild type (Figure 2). No intermediate such as 2, 4 or 3 was accumulated in the culture, indicating LovG is involved in the early part of the pathway. The significant attenuation of 1 biosynthesis indicates that lovG is intimately involved in the lov pathway, but not absolutely essential for the production of 1. This is not unexpected given our previous findings: an endogenous TE in A. terreus may be recruited for the hydrolysis of 2, albeit at a much lower efficiency. In a recent study, the region encoding lovG (between lovB and lovC) was replaced by sequences encoding the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) module from the CheA PKS-NRPS to yield LovB fused with a NRPS module.[14] The authors observed a similar reduction in the level of 1, and attributed the drop in yield to the reduced efficiency of the chimeric LovB.[14] From the results shown in Figure 2, we believe the decrease titer of 1 in that study can also be from the unintended deletion of lovG.

Figure 2.

Metabolic profiles of fermentation extracts from cultures of different A. terreus strains. A) HPLC chromatograms at 238 nm and the extracted ion chromatograms of observed masses m/z [M+Na]+ 445 corresponding to 1 in wild type A. terreus. B) HPLC chromatograms at 238 nm and the extracted ion chromatograms of observed masses m/z [M+Na]+ 445 corresponding to 1 in ΔlovG A. terreus mutant. The traces are drawn to the same scale.

To further confirm the hydrolytic role of LovG, we probed the direct involvement of this enzyme in turnover of 2 by in vitro and in vivo reconstitution assays. First, LovG was expressed and purified as N-terminal His-tagged protein from E. coli BL21(DE3). Chaperone proteins GroES/EL, DnaK/J and GrpE were co-expressed[15] to assist the folding of LovG and to improve the solubility (Figure S5). By incubating equimolar amounts (10 µM) of purified LovB, LovC and LovG with malonyl-CoA and the necessary cofactors (NADPH, SAM) for 12 hours at 25°C, we observed production of 2 in the assay without the need to add either base (1M KOH) or heterologous TE (Figure 3B). With LovG included, the turnover rate of 2 was estimated to be ~ 0.12 hour−1. (Figure S6) The slow, albeit observable turnover may be due to the large fraction of recombinant LovB being inactive in the in vitro assay as previously noted.[6b] Furthermore, lovG was cloned under S. cerevisiae ADH2 promoter and coexpressed with lovB and lovC. This resulted in the production of 2 from S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA at an elevated titer of ~35 mg/L after ~50 hours of culturing (Figure 3A, Figure S7). Collectively, these results confirmed LovG is the natural releasing partner of LovB during lovastatin biosynthesis in A. terreus.

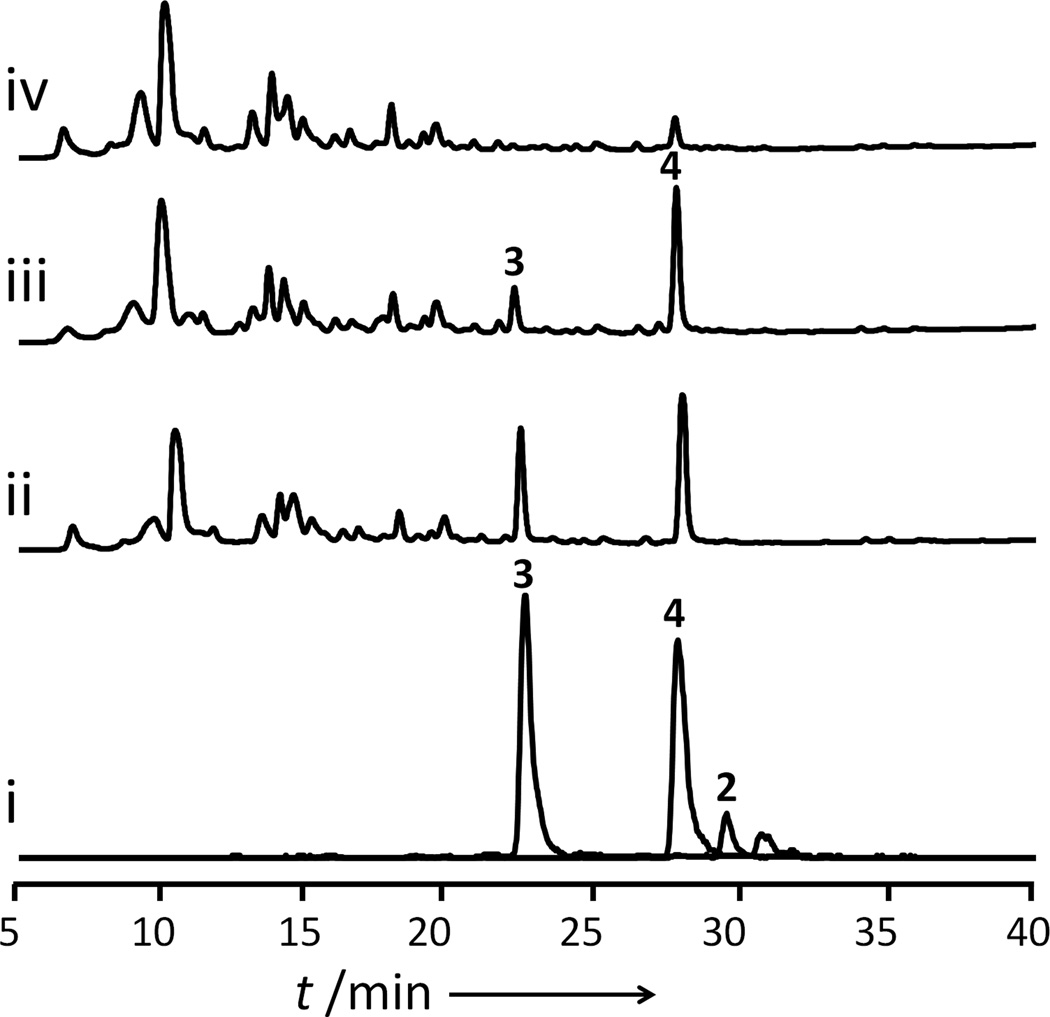

The successful production of 2 following LovG coexpression prompted us to examine the ability of the yeast host to produce more advanced intermediates such as the desired 3. The 2µ vector encoding both lovA and the endogenous A. terreus cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CPR) from A. terreus[6c] was introduced into BJ5464-NpgA and coexpressed with LovB, LovC and LovG. In the absence of expression of LovA and CPR, which are controlled by the divergent GAL1-GAL10 promoter, we were only able to observe the accumulation of 2. When galactose was added to the culture media at day 2, nearly all of 2 was oxidized to 4 and 3. After 48 hours, both 3 and 4 can be detected from the yeast culture at ~ 20 mg/L each (Figure 4). It is important to note here that this initial demonstration of biosynthesis of 3 has not been optimized. All five of the lov enzymes were expressed episomally from three separate 2µ vectors. With additional metabolic engineering approaches, we expect the conversion from 4 to 3, as well as the titer of 3 can be significantly improved.

Figure 4.

Production of 3 from S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA co-expressing LovB, LovC, LovG, LovA and A. terreus cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CPR). i) Extracted ion chromatograms showing detection of 2, 3 and 4 in culture 48 hours after induction of LovA and CPR expression. m/z [M−H]− for 2: 323, 3: 337 and 4: 321. ii–iv) HPLC Chromatograms at 238 nm of fermentation extracts. ii) 48 hours after induction of LovA and CPR expression; iii) 24 hours after induction of LovA and CPR expression iv) Before induction of LovA and CPR expression.

LovG joins a growing list of fungal TEs that are involved in product release via either hydrolysis or acyl transfer to an on-pathway intermediate (such as LovD[6a]). All of the TEs associated with HR-PKSs characterized to date are stand-alone enzymes, in contrast to the fused TE domains in mammalian fatty acid synthases (FAS)[16] or some of the nonreducing PKSs (NR-PKS), in which the fused TE can act as Claisen-like Cyclases (TE/CLC).[17] Recently, TE/CLCs from NR-PKS was also shown to possess editing functions during the PKS function and hydrolyze stalled products.[18] Given that LovB is noted to be highly accurate in the assembly of 2 as a sole product both in vitro and here, in vivo, we hypothesized that LovG may exert proofreading functions during the iterative LovB functions to remove aberrant tailored products. This function can ensure the timely offloading of incorrect, stalled intermediates and free LovB for more efficient turnover of 2.

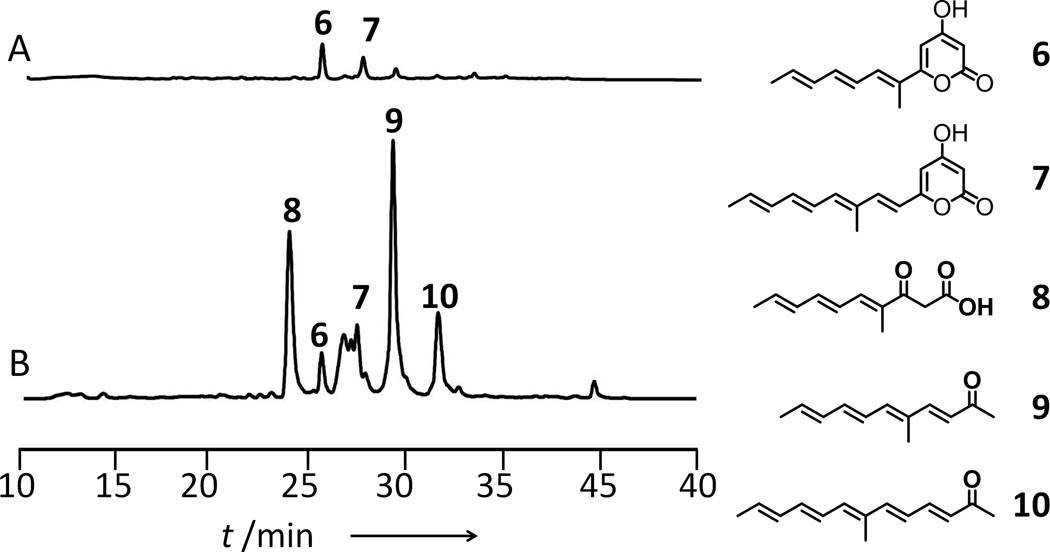

To assay the possible editing function of LovG, we performed in vitro reconstitution experiments in the absence of LovC, of which the earliest function in the pathway is to reduce the α–β enoyl intermediate at the tetraketide stage. We previously observed small amounts of offloaded products from LovB in the forms of methylated, conjugated α-pyrones such as 6 and 7 (Figure 5A) via continued chain elongation and spontaneous esterification); and ketones (not visible at the scale drawn in Figure 5A) via hydrolysis of β-keto thioesters and decarboxylation), when LovC is excluded.[4, 6b] Upon addition of LovG at equimolar concentration to LovB, the in vitro assay mixture turned significantly more yellow and the extract contained high amounts of offloaded products 8–10, in addition to 6 and 7 (Figure 5B). The compounds 8–10 were not stable and precluded the precise structural determination by NMR. However, through comparison of UV absorption spectra and mass increase upon using [2-13C] malonate (Figure S8–S12), as well as previously deciphered programming rules of LovB[6b], we were able to deduce the structures of these compounds as shown in Figure 5. 8 is a hydrolyzed β-keto acid, while 9 and 10 are ketones resulting from the decarboxylation of longer polyene β-keto acids. Interestingly, while the levels of 8–10 are high in the LovG-containing assay, the relative amounts of pyrones 6 and 7 remained nearly the same as in assay with LovB alone, indicating that LovG can readily hydrolyze the incorrectly tailored, β-keto thioesters from LovB to give 8–10. In contrast, the spontaneous hydrolysis of β-keto intermediates is much slower without LovG, resulting in LovB having to offload the products through an additional round of chain elongation, which can then be cyclically released as 6 and 7 (Figure S13). A recent study showed that NR-PKS TEs can also promote the formation of pyrones.[19] Therefore, LovG may also assist in the formation of 6 and 7, albeit likely at a much lower level as evident in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

LovG releases aberrant products from LovB. HPLC Chromatograms are extracted at 330 nm. A) in vitro assay with LovB; B) in vitro assay with LovB + LovG;

In conclusion, we have identified LovG as a multifunctional esterase from the lovastatin gene cluster. LovG is not only involved in the release of the correct product 2 from LovB, but is also shown to play a role in the clearance of aberrant intermediates from LovB. Construction of the LovG-containing pathway capable of de novo synthesis of 3 also opens up new metabolic engineering opportunities for statin production from yeast.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (1R01GM085128 and 1R01GM092217) to Y.T. Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Canada Research Chair in Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry to J. V. We thank Prof. D. K. Ro for providing the expression plasmid of LovA.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Wei Xu, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 (USA).

Yit-Heng Chooi, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 (USA).

Jin W. Choi, Department of Chemical Engineering and Material Science, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697 (USA)

Shuang Li, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 (USA); School of Bioscience and Bioengineering, South China, University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, PR China.

John C. Vederas, Department of Chemistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton Alberta, T6G 2G2, Canada

Nancy A. Da Silva, Department of Chemical Engineering and Material Science, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697 (USA)

Yi Tang, Email: yitang@ucla.edu, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 (USA).

References

- 1.Alberts AW, Chen J, Kuron G, Hunt V, Huff J, Hoffman C, Rothrock J, Lopez M, Joshua H, Harris E, Patchett A, Monaghan R, Currie S, Stapley E, Albers-Schonberg G, Hensens O, Hirshfield J, Hoogsteen K, Liesch J, Springer J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:3957–3961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J. Science. 2001;292:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie XK, Tang Y. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:2054–2060. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02820-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy J, Auclair K, Kendrew SG, Park C, Vederas JC, Hutchinson CR. Science. 1999;284:1368–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrickson L, Davis CR, Roach C, Nguyen DK, Aldrich T, McAda PC, Reeves CD. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:429–439. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Xie X, Meehan MJ, Xu W, Dorrestein PC, Tang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8388–8389. doi: 10.1021/ja903203g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ma SM, Li JW, Choi JW, Zhou H, Lee KK, Moorthie VA, Xie X, Kealey JT, Da Silva NA, Vederas JC, Tang Y. Science. 2009;326:589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1175602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Barriuso J, Nguyen DT, Li JW, Roberts JN, MacNevin G, Chaytor JL, Marcus SL, Vederas JC, Ro DK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8078–8081. doi: 10.1021/ja201138v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie X, Watanabe K, Wojcicki WA, Wang CC, Tang Y. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KK, Da Silva NA, Kealey JT. Anal. Biochem. 2009;394:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, Zhou H, Wirz M, Tang Y, Boddy CN. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6288–6290. doi: 10.1021/bi9009049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou H, Qiao K, Gao Z, Meehan MJ, Li JW, Zhao X, Dorrestein PC, Vederas JC, Tang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4530–4531. doi: 10.1021/ja100060k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auclair K, Kennedy J, Hutchinson CR, Vederas JC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1527–1531. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe Y, Suzuki T, Ono C, Iwamoto K, Hosobuchi M, Yoshikawa H. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2002;267:636–646. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0697-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YP, Yuan GF, Hsieh SY, Lin YS, Wang WY, Liaw LL, Tseng CP. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:287–293. doi: 10.1021/jf903139x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boettger D, Bergmann H, Kuehn B, Shelest E, Hertweck C. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:2363–2373. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishihara K, Kanemori M, Kitagawa M, Yanagi H, Yura T. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:1694–1699. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1694-1699.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maier T, Leibundgut M, Ban N. Science. 2008;321:1315–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1161269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii I, Watanabe A, Sankawa U, Ebizuka Y. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vagstad AL, Bumpus SB, Belecki K, Kelleher NL, Townsend CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6865–6877. doi: 10.1021/ja3016389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman AG, Vagstad AL, Belecki K, Scheerer J, Townsend CA. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2012;48:11772–11774. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36010a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.