Abstract

Oxidation-specific epitopes (OSE), present on oxidized LDL (OxLDL), apoptotic cells, cell debris and modified proteins in the vessel wall, accumulate in response to hypercholesterolemia, and generate potent pro-inflammatory, disease-specific antigens. They represent an important class of ‘danger associated molecular patterns’ (DAMPs), against which a concerted innate immune response is directed. OSE are recognized by innate ‘pattern recognition receptors’, such as scavenger receptors present on dendritic cells and monocyte/macrophages, as well as by innate proteins, such as IgM natural antibodies and soluble proteins, such as C-reactive protein and complement factor H. These innate immune responses provide a first line of defense against atherosclerosis-specific DAMPs, and engage adaptive immune responses, provided by T and B-2 cells, which provide a more specific and definitive response. Such immune responses are ordinarily directed to remove foreign pathogens, such as those found on microbial pathogens, but when persistent or maladaptive, lead to host damage. In this context, atherosclerosis can be considered as a systemic chronic inflammatory disease initiated by the accumulation of OSE type DAMPs and perpetuated by maladaptive response of the innate and adaptive immune system. Understanding this paradigm leads to new approaches to defining cardiovascular risk and suggests new modes of therapy. Therefore, OSE have become potential targets of diagnostic and therapeutic agents. Human and murine OSE-targeting antibodies have been developed and are now being used as biomarkers in human studies and experimentally in translational applications of non-invasive molecular imaging of oxidation-rich plaques and immunotherapeutics.

Atherogenesis and the immune system

It is now apparent that both innate and adaptive immune responses are intimately involved in atherogenesis. Much progress has been made over the past two decades in understanding the contributions of the various components of innate and adaptive immunity in atherogenesis, which is beyond the scope of this brief review. We refer the reader to a number of more comprehensive reviews on this topic [1–7].

Atherosclerosis is a systemic chronic inflammatory disease that affects all medium and large blood vessels and is the leading cause of death worldwide. Extensive research over the last two decades has revealed that both adaptive and innate immunity play key roles in the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic lesions. The response-to-retention model of atherogenesis explains the subendothelial retention of low density lipoproteins (LDL) present in excess in the circulation that is facilitated by specific matrix proteins in the arterial wall [8]. Oxidation of LDL (OxLDL) trapped in the intima, and the resulting enhanced lipid peroxidation, is widely regarded as a vital step in atherogenesis [9••,10]. This results in the generation of a wide variety of oxidized lipids and oxidized lipid-protein adducts, termed ‘oxidation-specific epitopes’ (OSE) [5], which are immunogenic, pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic. OSE on OxLDL, such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and oxidized phospholipid (OxPL) epitopes, lead to enhanced uptake of OxLDL by macrophages, resulting in generation of macrophage-derived foam cells and ultimately advanced atherosclerotic lesions [11••]. OSE also lead to changes in gene expression in arterial wall cells that lead to recruitment of monocytes and their differentiation into macrophages, as well as recruitment of lymphocytes, which together mediate inflammation, leading to progression and destabilization of more advanced lesions [12].

OSE represent a collection of ‘danger-associated molecular patterns’ (DAMPs) that promote tissue damage and cell death if not removed. They are present not only on OxLDL, but on apoptotic cells, apoptotic blebs and cellular debris. OSE are recognized by ‘pattern recognition receptors’ (PRRs) of innate immunity, which are primitive trans-membrane proteins selectively targeting immunogenic self-antigens (i.e. DAMPs) that need to be removed from damaged tissues [13,5]. In addition, these same PRRs often recognize ‘pathogen associated molecular patterns’ (PAMPs) on microbial antigens. Indeed, many DAMPs and PAMPs share molecular or immunological identity. There are cellular PRRs, such as macrophage scavenger receptors (SRs) and toll like receptors (TLRs), as well as by soluble PRRs, including innate natural antibodies (NAbs) and soluble proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and complement factor H (CFH) (Table 1).

Table 1. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in atherosclerosis.

| Receptor | Ligands | Cell types |

|---|---|---|

| Scavenger receptors (SRs) [19,70] | ||

| SR-A1 | AcLDL, MDA-LDL, OxLDL, -amyloid, molecular chaperones, ECM, AGE, apoptotic cells, activated B-cell, bacteria | Macrophages, mast, dendritic, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells |

| SR-B1 | HDL, LDL, OxLDL, PC of OxPL, and apoptotic cells | Monocytes/macrophages, hepatocytes, adipocytes |

| CD36 | AcLDL, OxLDL, HDL, LDL, VLDL, amyloid, AGE, apoptotic cells, OxPS, PC of OxPL | Macrophages, platelets, adipocytes, epithelial and endothelial cells |

| LOX-1 | OxLDL, molecular chaperones, ECM, AGE, apoptotic cells, activated platelets, bacteria | Endothelial and smooth muscle cells, macrophages, platelets |

| SRECI/II | AcLDL, OxLDL, molecular chaperones and HSPs, apoptotic cells | Endothelial cells, macrophages, CD8+ cells |

| SR-PSOX | OxLDL, bacteria | Macrophages, smooth muscle, dendritic, and endothelial cells, and B-cells and T cells |

| Toll-like receptors (TLRs)[22,23,25] | ||

| TLR1 | Lipopeptides | Monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, B cells |

| TLR2 | Extracellular matrix molecules, HMGB1, HSP60/70, BLP of Gram-positive bacteria | Monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells |

| TLR3 | dsRNA, costimulation with SRECI/II | Dendritic cells, B cells |

| TLR4 | mmLDL, OxLDL, OxPAPC, HSP22/60/70/72, HMGB1, LPS of Gram-negative bacteria, fibrinogen | Monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, B cells |

| TLR6 | Lipopeptides | Monocytes/macrophages, mast cells, B cells |

| Soluble PRRs [71] | ||

| Natural antibodies (NAbs) | ||

| EO6/T15 IgM | PC of OxPL | |

| NA-17 IgM | MDA-LDL | |

| LRO1 IgM | OxCL | |

| Natural IgM | 4-HNE | |

| CRP | PC of OxPL | |

| CFH | MDA epitopes | |

SR-A: scavenger receptor class A, AcLDL: acetylated low density lipoprotein, MDA: malondialdehyde, OxLDL: oxidized low density lipoprotein, ECM: extracellular matrix, AGE: advanced glycation end products, HDL: high density lipoprotein, LDL: low density lipoprotein, VLDL: very low density lipoprotein, OxPS: oxidized phosphorylserine, LOX-1: lectin-like oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor-1, SRECI/II: scavenger receptor expressed by endothelial cells I and II, SR-PSOX: scavenger receptor for phosphatidyl serine and oxidized low density lipoprotein (identical to chemokine CXCL16), HMGB1: high-mobility group protein B1 (intracellular and nuclear protein), BLP: bacterial lipoprotein, LPS: lipopolysaccharides. PC: phosphocholine, OxPL: oxidized phospholipids, OxCL: oxidized cardiolipin, 4-HNE: 4-hydroxynonenal, CRP: C-reactive protein, CFH: complement factor H.

The innate immune system provides a powerful first line of defense against DAMPs and the response of innate immunity is inflammation. In addition, innate recognition of DAMPs is a prerequisite for adaptive immune responses, and mediates the subsequent recruitment of lymphocytes that mediate adaptive responses, which then provides specific and more definitive responses. While this coordinated immune response is highly effective in protecting an organism against infectious pathogens, in the case of chronic antigenic stimulation, as occurs in the context of sustained hypercholesterolemia, and/or in the setting of unbalanced regulation, injury to the host may occur. Indeed, one may view atherogenesis as a chronic and maladaptive inflammatory response to OSE and related antigens consequent to persistent hypercholesterolemia. Understanding these responses may provide insight into the mechanisms that sustain and drive the progression of atherosclerosis from the early foam cell lesion into advanced lesions.

Vascular inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions involves a complex cellular network, with monocyte-derived macrophages playing an early and vital role. Blood-derived monocyte attraction into the arterial wall is influenced by chemokines released from activated endothelial cells (EC), macrophages and resident lymphocytes and mediated through endothelial cell adhesion molecules such as selectins, integrins, ICAM and VCAM that are highly expressed by activated endothelial cells in proximity to atherosclerotic lesions [14]. Once resident in the arterial intima, monocytes mature into macrophages, express PRRs on their cell surface, produce proinflammatory mediators, accumulate oxidized lipids and cholesterol and subsequently transform into foam cells [15,9••,16].

Oxidized LDL is taken up in an unregulated manner by macrophage SRs, leading to cholesterol accumulation as cytoplasmic lipid droplets to prevent the toxic effects of free cholesterol. Defective efflux mechanisms and defective cholesterol esterification ultimately leads to foam cell transformation in advanced lesions and to macrophage death in the necrotic core [17,2]. Although foam cell formation has been classically thought to be involved with a pro-inflammatory phenotype, recent lipidomic and transcriptomic studies evaluating the effect of a high fat diet on peritoneal macrophage cholesterol accumulation has shown that foam cell formation per se was associated with suppression, rather than activation, of inflammatory gene expression [18••]. Interestingly, accumulation of desmosterol, the penultimate intermediate in cholesterol biosynthesis, was found to be a key regulator of an anti-inflammatory response in foam cells, leading to LXR mediated suppression of inflammatory genes, SREBP target genes, and selective reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism. These observations suggest that cholesterol accumulation in macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions per se does not mediate the known proinflammatory phenotype. Rather it implicates extrinsic, proinflammatory signals generated within the artery wall, for example those that might occur secondary to OxPLs, that suppress homeostatic and anti-inflammatory functions of desmosterol [9••].

Eight classes of SRs have been discovered, all of which bind to some extent host-derived ligands in addition to pathogenic epitopes [19]. Macrophage SRs that bind OxLDL are listed in Table 1, but the relative contributions of these to atherogenesis in vivo is not known with certainty. In cell culture, CD36 and SR-A appear to be primarily responsible for uptake of OxLDL, but deletion of these receptors in murine models has yielded mixed results on their impact on atherogenesis [20,21]. It should be appreciated that in vivo deletion of one or even two such SRs may have led to upregulation of other SRs. In addition, SRs with lower affinity to OxLDL may still mediate sufficient OxLDL uptake to lead to foam cell formation in the presence of a large excess of extracellular OxLDL.

At least 13 types of TLRs with distinct ligand specificities mediating leukocyte recruitment and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, chronically activating innate immunity and exacerbating inflammation have been described [22]. However, only a few of these have been examined for their relationship to atherogenesis. Evidence for a proatherogenic role of TLR2 has been presented, but the mechanisms by which this occur and the responsible ligands appear complex [23]. In the context of a high fat diet (HFD), the presence of TLR2 in Ldlr–/– mice is proatherogenic, mediated by non-bone-marrow-derived cells (BMDC), such as EC, which are known to express TLR2 at sites of low shear stress. Infusion of the synthetic exogenous agonist Pam3 CSK4 was also atherogenic, but in this case, the atherogenicity appears to be mediated by BMDC, which includes lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells [24]. TLR2 forms heterodimers with TLR1 or TLR6. However, deficiency of TLR1 or TLR6 did not diminish HFD-driven disease. In contrast, when HFD-fed Ldlr–/– mice were challenged with Pam3 or MALP2, specific exogenous ligands of TLR2/1 or TLR2/6, respectively, atherosclerotic lesions developed with remarkable intensity in the abdominal segment of the descending aorta. In contrast to atherosclerosis induced by the endogenous agonists, these lesions were diminished by deficiency of either TLR1 or TLR6 [25]. Importantly, the endogenous ligands generated from a HFD that promote disease by TLR2 remain to be identified. In this context, it is of interest that OxPL have been shown to promote inflammatory gene expression in macrophages and that this is mediated by TLR2 in part [26••,27].

TLR4 and its adapter protein MyD88 have also been shown to be proatherogenic in hyperlipidemic Apoe–/– and Ldlr–/– mice [28,29]. Bone marrow transplants from Tlr4–/– mice into Ldlr–/– recipients decreased atherogenesis, implying macrophage expression of TLR4 is atherogenic. These results strongly imply that one or more endogenous DAMPs activate TLR4 in vascular cells, leading to proinflammatory effects.

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are classic TLR4 agonists and there is much speculation that so called ‘metabolic endo-toxemia’, in which there is an increased absorption of LPS in the gastrointestinal tract in the presence of obesity, could contribute to low-grade chronic macrophage inflammation [30]. Studies from Miller and colleagues have shown that oxidized cholesteryl esters (OxCE), as found in early forms of OxLDL, potently activate macrophage inflammatory gene expression via a TLR4 dependent process [31••,32]. In addition, OxCE induces enhanced macrophage phagocytosis and enhanced uptake of both native and OxLDL. Thus, both LPS and OxCE activate TLR4 dependent pathways, but because they use different signaling pathways downstream of TLR4, sub-threshold levels of each, when added together, can additively or synergistically generate proatherogenic macrophage responses [33]. This suggests a mechanism in vivo by which chronic activation of macrophage inflammatory pathways may occur.

Other soluble components, such as CFH and pentraxins such as CRP also play key roles as PRRs of the innate immune system. CFH is the major inhibitor of the alternative pathway of complement activation and was recently shown to bind to and prevent the proinflammatory effects of MDA epitopes, which are present in the eye of patients with age related macular degeneration (AMD), as well as in early and late human atherosclerotic lesions [34••,35,11••]. A well-described snp in CFH, which is a major risk factor for AMD, dramatically inhibits the ability of CFH to bind MDA, suggesting that the inability of the variant CFH to bind MDA contributes to the pathogenesis of AMD [34••]. Similarly, CRP, was first described for its ability to bind to microbial pathogens via the phosphocholine (PC) moiety and mediate clearance. However, it is now recognized that it also binds the PC headgroup of OxPL, and by this mechanism binds to and mediates enhanced clearance of apoptotic cells [36].

Finally, we have recently shown that OSE are a major target of innate IgM NAbs in both mice and humans, and that up to 30% of all such NAbs bind OSE [37••]. For example, we cloned the prototypic IgM NAb E06, which binds to the PC moiety of OxPL present on OxLDL or apoptotic cells. In vitro, E06 can inhibit the binding of OxLDL to macrophage SRs, and when its titer is elevated in vivo in hypercholesterolemic mice, it is atheroprotective [38••]. Indeed, atherosclerosis is greatly enhanced in hypercholesterolemic mice that are unable to secrete IgM antibodies [39••].

Adaptive immunity also exerts profound and diverse effects on atherogenesis. These responses are multilayered and complex, befitting the important task of distinguishing between self and foreign, and promoting protective defenses while not provoking injury to self. While atherosclerosis can proceed in the complete absence of adaptive immunity, its presence profoundly modulates disease progression, conferring both protective as well as proatherogenic responses. On balance, one may consider adaptive responses to be proatherogenic. We refer the reader to many excellent reviews on the role of adaptive immunity in atherogenesis [1,3,4,6,7].

In essence, once initiated by inappropriately elevated levels of plasma LDL, atherogenesis reflects the net balance between proatherogenic and atheroprotective subsets of immune cells and their products, between subsets of Treg cells and T effector cells, between B-2 cells that make conventional IgG adaptive antibodies and B-1 cells that make innate IgM, and between various subsets of monocytes/macrophages.

Oxidation-specific epitopes are a major class of atherosclerosis relevant antigens

The term OxLDL defines a variety of oxidative modifications of the polyunsaturated fatty acids present in phospholipids, cholesteryl esters and triglycerides of LDL. Such OSE in OxLDL are present in both the lipid phase and covalently bound to apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB) via the ε-amino group of lysines. OxLDL has been identified as a key disease-specific antigen and a major cause of inflammation in atherosclerosis, and studies more than 20 years ago documented its presence in animal and human arterial lesions (reviewed in [9••,40]). As noted above, many OSE share molecular or immunological identity with PAMPs on microbial pathogens, as well as on apoptotic cells. Thus OSE are recognized by a common set of innate PRRs. For example, the PC moiety found on OxPL of OxLDL and apoptotic cells is recognized by SRs CD36 and SR-B1, by the innate IgM NAb E06, and by CRP. Similarly the PC present on the cell wall of S. pneumonia (but not as a phospholipid) is similarly recognized by the same set of PRRs (reviewed in [5]). We have shown that immunizing cholesterol-fed Ldlr–/– mice with heat killed S. pneumoniae raises the titers of E06 and this leads to atheroprotection [38••]. We have postulated that innate immune responses have been evolutionary selected to provide homeostasis against the inflammatory properties of OSE, and that this has been secondarily reinforced by the fact that these same innate responses often provide protection against microbial pathogens as well [5]. In principle, this suggests that many innate immune responses against OSE, such as those provided by IgM NAbs, are likely to be of overall benefit and that one might exploit these observations to develop novel and effective therapeutic options to inhibit inflammation and atherogenesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Immunologic targets and receptors in atherosclerosis. (a) Pattern-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) comprise phosphocholines (PC) on bacterial cell membranes, lipopeptides and lipopolysaccharides (LPS). (b) Danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) include oxidized phosphocholine (OxPC), advanced glycation end-products (AGE). (c) OxLDL defines a variety of oxidative modifications various components of LDL, the best characterized of which are oxidized phospholipids (OxPL), Malondialdehyde (MDA), and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) epitopes. Lp(a) is composed of apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB) and apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)] and carries OxPL in both the lipid and protein phases. OxPL are also present on plasminogen. (d) Cellular innate immunity is provided by T and B cells, dendritic cells and macrophages/foam cells, which communicate via cytokines. (e) Membrane bound PRRs include trans membrane proteins on members of cellular innate immunity and recognize DAMPs, PAMPs, and OSEs. (f) Natural antibodies (NAbs) of IgM (EO6/T15) and IgG isotypes, complement factor H (CFH), and C-reactive protein (CRP) constitute soluble pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). (g) OxPL, MDA and 4-HNE moieties represent well described oxidation specific epitopes (OSEs).

Biotheranostic applications

Since OSE mediate proinflammatory pathways and lesion formation in atherogenesis, they have become viable targets for developing in vitro diagnostics (biomarkers), therapeutic agents and diagnostic molecular imaging probes (biotheranostics). Human and murine antibodies targeting OSE have been developed and are now being used as biomarkers in experimental and human translational studies, coated on nanoparticles to provide non-invasive imaging of oxidation-rich plaques and immunotherapeutics to reduce the rate of atherogenesis. Below, we provide examples of such biotheranostic applications targeting OSEs (Figure 2).

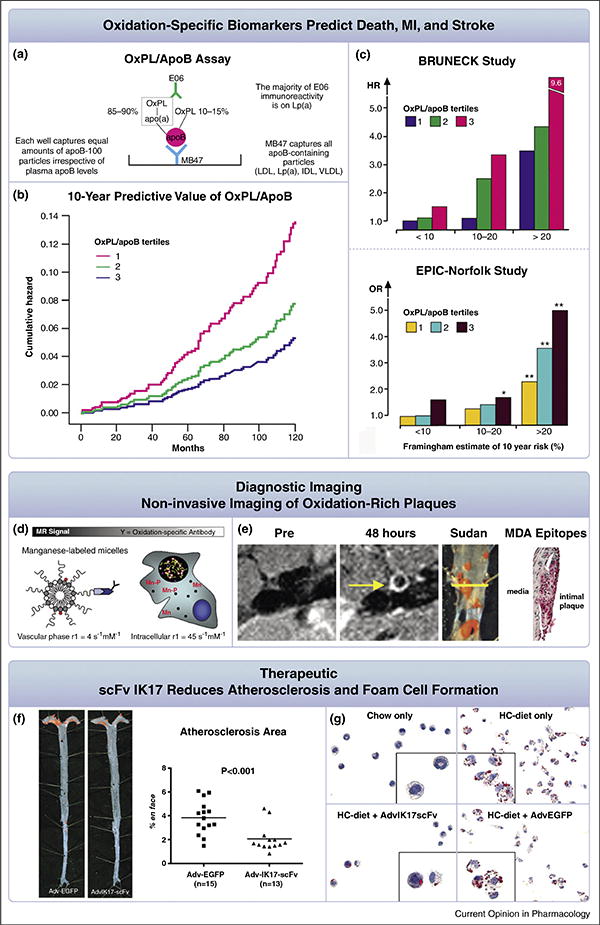

Figure 2.

Biotheranostic applications of oxidation-specific antibodies. Panels (a–c) summarize oxidized phospholipid (OxPL) biomarkers. The OxPL/apo B assay (OxPL/apoB) reflects the content of OxPL on apoB particles captured on microtiter well plates (a). The assay is set up so that all plates capture a similar amount of apoB and therefore the assay is normalized to and independent of plasma apoB and LDL-C levels. Designed this way, the assay is highly sensitive to the number of moles of OxPL on apoB and primarily reflects the OxPL content on the most atherogenic Lp(a) particles (high Lp(a) levels mediated by small apo(a) isoforms). (b) shows the 10-year predictive value of OxPL/apoB in death, MI and stroke in the prospectively followed Bruneck population representing a cross-section of the general community. (c) shows the value of OxPL/apoB in enhancing stratification of CVD risk in different categories of the Framingham Risk Score in the Bruneck and EPIC-Norfolk studies. Panels d–e display the molecular imaging of oxidation-specific epitopes (OSE). Nanoparticles (∼10–15 nm) consisting of micelles are generated to contain manganese (Mn) and an oxidation-specific antibody (d). The relaxivity (r1) is increased ∼10-fold when this particle binds to extracellular OxLDL, is then taken up by macrophages and released intracellularly as free Mn, becoming an indirect macrophage-targeting agent. Successful non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging of OSE is accomplished by injection of these nanoparticles and imaging of the abdominal aorta in cholesterol fed apoE–/– mice (e). Note lack of signal at the pre-injection scan and strong signal (white contrast) in the 48 hour scan. The accompanying panels show the Sudan stained aorta where the imaging occurred and the presence of the OSE MDA using immunostaining techniques, confirming both the presence of plaque and MDA epitopes at the imaged area. Panels f–g represent the therapeutic use of the oxidation-specific antibody IK17 used as a single chain fragment. Adenovirus IK17-scFv-mediated hepatic expression was achieved in LDLR/Rag 1 double-knockout mice, leading to a 46% reduction in en face atherosclerosis compared with control mice treated with adenovirus-enhanced green fluorescent protein Adv-GFP) vector (f). Importantly, peritoneal macrophages isolated from Adv-IK17-scFv treated mice had decreased lipid accumulation compared with adv-GFP (g), consistent with the ability of IK17 to inhibit OxLDL uptake by macrophages. Figures reprinted with permission from references: panel b [68], c [68,69], panels d and e [47] and panel f [59••].

Biomarkers

Biomarkers that are putatively involved in causal pathways of inflammation and atherogenesis would be an attractive addition to the clinical armamentarium, may predict therapeutic response, and may define therapeutic targets. A summary of OSE biomarkers relevant to atherosclerosis is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Inflammatory biomarkers in human atherosclerotic disease.

| Biomarker family | Examples |

|---|---|

| Danger associated patterns (DAMPs) | |

| Oxidation-specific epitopes (OSE) | PC containing |

| OxPL (POVPC, | |

| OxPAPC) | |

| MDA-LDL | |

| Cu-OxLDL | |

| 4-HNE | |

| OxCE | |

| OxCL | |

| Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) | AGE-LDL |

| Pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) | LPS |

| Circulating natural autoantibodies to DAMPs | EO6, T15, |

| ?IgMs to OSE | |

| Autoantibodies and Immune complexes to OSE | MDA-LDL IgG |

| CuOxLDL IgG | |

| OxCL IgG | |

| ApoB-IC IgG | |

| Acute phase response | hsCRP |

PC: phosphocholine, OxPL: oxidized phospholipids, POVPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-oxovaleroyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, OxPAPC: oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, MDA: malondialdehyde, LDL: low density lipoprotein, CuOxLDL: copper oxidized LDL, 4-HNE: 4-hydroxynonenal, OxCE: oxidized cholesteryl ester, apoB-100: apolipoprotein B-100, apo(a): apolipoprotein (a), OxCL: oxidized cardiolipin, LPS: lipopolysaccharides, hsCRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. A comprehensive review of products of phospholipid peroxidation is found in Weismann et al. [72].

OxPL/apoB and Lp(a)

Through our work over the last decade, we have shown that lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] strongly binds OxPL [41••]. Lp(a), which is comprised of apolipoprotein (a) [apo(a)] covalently bound via a disulfide bond to apoB of LDL is now generally recognized as a causal, independent, genetic risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and myocardial infarction (MI) and has become a target of therapy for reducing cardiovascular risk [42,43]. Lp(a) has been shown to be a preferential lipoprotein carrier of OxPL. We have developed methods to measure OxPL on apoB particles (OxPL/apoB) using a chemiluminescent ELISA technique. Measurement of OxPL/apoB primarily reflects the content of OxPL on Lp(a) and accounts in part for the proatherogenic activity of Lp(a). Because small apo(a) isoforms are associated with high Lp(a) plasma levels, and because these lipoproteins contain the most OxPL content, the OxPL/apoB measurement is primarily a reflection of the most atherogenic Lp(a) particles. Elevated levels of OxPL/apoB reflect endo-thelial dysfunction, predict the presence and progression of cardiovascular disease in multiple beds, and predict death, MI and stroke in unselected populations (reviewed in Taleb et al. [44]). Importantly for clinical applications, measuring OxPL/apoB allows reclassification of approximately 30% of unselected subjects from the general community defined as being in intermediate risk categories into either lower or higher risk categories, which is clinically relevant in that it would influence and optimize clinical treatment decision in a large number of patients [45••]. This assay will be available soon to the research and clinical communities.

Oxidized phospholipids and plasminogen function

We have recently shown that interactions of OxPL with the immune system extend to the fibrinolytic system [46••]. Apo(a) is highly homologous to plasminogen, which is acted upon by tissue plasminogen activators and converted into plasmin that then mediates breakdown of fibrin clots. We have demonstrated that plasminogen also carries covalently-bound OxPL and represents a second major plasma pool of OxPL, in addition to those present on Lp(a). As opposed to OxPL on Lp(a), which predict increased cardiovascular risk, OxPL on plasminogen are associated with enhanced potential to potentiate fibrinolysis and thus may be associated with reduced atherothrombotic risk. This is supported by experiments showing that enzymatic removal of OxPL from plasminogen resulted in a longer lysis time for fibrin clots as measured in in vitro assays [46••], that is the presence of covalently bound OxPL on plasminogen makes it a better substrate for formation of plasmin. In clinical studies, OxPL/plasminogen levels remained stable in normal subjects or in patients with stable CVD followed serially over time, but increased acutely over the first month in patients following acute myocardial infarction, implying that OxPL/plasminogen may be a novel biomarker of acute coronary syndromes and may also be involved in the pathogenesis or destabilization of atherosclerotic lesions. Ongoing studies are evaluating the pathophysiological implications of OxPL on plasminogen and outcome studies are underway to assess whether OxPL/plasminogen predicts risk of future cardiovascular events.

Molecular imaging

Oxidation-specific antibodies have been used extensively for immunostaining of atherosclerotic lesions in human artery specimens. In a recent study by van Dijk et al. [11••], we showed that human atherosclerotic lesions manifest a differential expression of different OSEs and apo(a) as they progress, rupture, and become clinically symptomatic. OSEs and apo(a) were absent in normal coronary arteries and minimally present in early lesions. As lesions progressed, apoB and MDA epitopes did not increase, whereas macrophages, apo(a), OxPL, and IK17 epitopes, representing advanced MDA-like epitopes, increased proportionally, but they differed according to plaque type and plaque components. Apo(a) epitopes were present throughout early and late lesions, especially in macrophages and the necrotic core. IK17 and OxPL epitopes were strongest in late lesions in macrophage-rich areas, lipid pools, and the necrotic core, and they were most specifically associated with unstable and ruptured plaques. The presence of OSEs in clinically relevant human lesions provides a strong rationale to develop techniques to image such lesions using oxidation-specific antibodies. In a series of experimental studies, we have shown that when attached to appropriate nuclear or magnetic resonance imaging probes, these oxidation-specific antibodies bind to their target in the vessel wall, are internalized by macrophages and provide excellent live images of experimental atherosclerotic lesions in vivo [47,48,49••]. Translation of these applications to humans may provide a means to detect and monitor such lesions and assess the efficacy of established or experimental therapies.

Immunotherapeutic approaches

Immunotherapeutic approaches can be simplistically divided into two classes: Passive immunization by infusing antibodies or fragments thereof that will directly bind to and inactivate a target; and classical active immunizations, whereby an immunogen is used in a vaccine strategy to provoke enhanced antibody titers that would provide long-term immunity, and/or induce tolerance to atherogenic immune responses. Amir et al. [50] provide a comprehensive collection of experimental immunotherapeutic approaches.

Passive immunization

The potential use of oxidation-specific antibodies to patients at risk of or having acute cardiovascular disease is increasingly being evaluated in pre-clinical and early phase studies. There are several observations to suggest that this approach may be viable: firstly, NAbs, such as E06, protect mice against atherosclerosis progression [38••,51], potentially by inactivating or clearing relevant antigens such as OxLDL; secondly, IgM antibodies in mice are atheroprotective and knockout of IgM is associated with higher risk of atherosclerosis progression [52,39••]; thirdly, IgM autoantibodies in human populations are associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and events, although this is not always independent of traditional risk factors [45••,53].

Several studies in experimental models have suggested that direct infusion of oxidation-specific antibodies is associated with lower rate of progression of atherosclerosis or enhanced regression of established lesions. For example, infusion of anti-PC-IgM T15 against PC in mice showed no change in native atherosclerosis, but reduced atherosclerosis in the inferior vena cava bypass grafted to the carotid artery, compared to a control polyclonal IgM [54]. Schiopu et al. demonstrated that human IgG antibody 2D03 directed against MDA-modified apoB inhibited progression of atherosclerosis [55], potentiated atherosclerosis regression (∼50%) in apobec–/–/Ldlr–/– mice [56], and reduced collar-induced carotid injury [57], compared to a control antibody directed to FITC-8.

In work from our laboratory, we have demonstrated that the human antibody IK17, cloned from a human phage-display library and directed to advanced MDA-like epitopes, either infused intraperitoneally as a Fab or overexpressed with an adenoviral vector as single-chain Fv fragment, significantly reduced atherosclerosis progression by ∼30–50% [58,59••]. Furthermore, sustained overexpression of IK17 in a zebrafish model of hypercholesterolemia, induced regression of oxidized lipid deposits [60]. Importantly, mechanistic information from these studies demonstrated reduced binding of OxLDL/MDA-LDL to macrophages and significant reduction in foam cell formation. This suggests that if these antibodies were to be used clinically, they would have the potential to acutely decrease OxLDL uptake and cholesterol accumulation in macrophages and potentially result in rapid plaque stabilization by preventing pro-inflammatory effects of foam cells.

A monoclonal human IgG1 antibody BI-204 (MLDL1278A, BioInvent and Genentech) has been evaluated in humans. A phase IIa multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study in 147 patients with stable coronary artery disease in addition to standard care, including statins, was designed to demonstrate reduction in plaque inflammation assessed by FDG-PET/CT imaging of the carotid arteries and aorta. Results of this study have not been published but were reported in the lay press as not meeting their primary endpoint.

As this field moves forward, OSE antibodies that are moved to the clinical frontier should be well characterized immunologically as to clinically relevant epitopes directly involved in inflammatory pathways and the atherosclerotic process, and there should be convincing data in animal models that the antibodies have anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects. Potential clinical applications of such antibodies include: firstly, acute in-hospital treatment of patient with recent myocardial infarction or unstable angina for plaque stabilization over the next 6–12 month period where the highest chance of recurrence occurs. Oxidation-specific antibodies have the potential to bind OxLDL present in the vessel wall and prevent its uptake by activated macrophages and thus ‘stabilize’ these lesions and prevent plaque rupture; secondly, acute treatment during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures, where we have shown that OxLDL and its associated oxidized lipids are liberated and may cause detrimental downstream effects to myocardium or other organs [44]. These antibodies could be given either in the emergency room setting or in the cardiac catheterization laboratory as an intravenous infusion to stabilize OxLDL-rich plaques and reduce the incidence of complications from either the disease or the PCI procedure; thirdly, chronic therapy for high-risk patients of recurrent cardiovascular events such as myo-cardial infarction or stroke; and fourthly, treatment of ‘vulnerable’ plaques when imaging techniques could detect them. These approaches would represent a novel therapeutic paradigm with no approved indications in cardiovascular disease to date and would broaden the therapeutic window for cardiovascular treatment.

Active immunization

Our laboratory made the seminal observation that immunization of Ldlr−/− rabbits with homologous MDA-LDL markedly reduced the extent of atherosclerosis [61], results confirmed and extended by many laboratories (reviewed in [38••,62,4,63]).

This strategy suggests immunization to raise antibody titers to OSE, which would then be predicted to bind to OSE and reduce their inflammatory properties and inhibit the uptake of OxLDL by macrophages. Immunization strategies following this principle have proven effectiveness in animal models and included injection of OSEs such as OxLDL, OxPC, MDA-LDL, PC-KLH, native and MDA-modified apoB peptides. Our group has also recently described the potential of peptide mimotopes mimicking MDA epitopes [64]. These mimotopes are small immunogenic peptides of <20 amino acids that immunologically mimic MDA type epitopes, and might be used to induce immunity against this OSE relevant antigen, which could be helpful in the development of an atheroprotective vaccine. Although all of these immunization strategies have reported variable efficacy in mice, it is currently unclear how to translate these observations to humans, as the importance of these various antibody populations in human disease is unknown.

There is now a growing body of experimental literature that an adaptive response to peptides of native apoB-100 of LDL promotes atherogenesis. Therefore, several groups have reported therapeutic approaches that attempt to promote tolerance against this response by different immunization schemes that utilize injections of various apoB peptides [65,66,67••]. This approach is currently under consideration by a pharmaceutical company for use in humans.

Conclusion

OSE on lipoproteins and other relevant epitopes generated and expressed in atherosclerotic lesions act as DAMPs and lead to immune recognition and activation. These responses can be proatherogenic but also protective as well. Understanding these responses will be of great value in providing novel approaches to the treatment and prevention of CVD. Already, a large experimental and clinical body of evidence suggests the potential of biotheranostic applications in targeting OSE with oxidation-specific antibodies. OSE can be measured on lipoproteins in plasma as biomarkers, detected in the vessel wall with molecular imaging techniques and targeted with human oxidation-specific antibodies for therapeutic purposes. Biomarker applications measuring oxidized phospholipids are already well established in patients, and future clinical trials will assess the role of molecular imaging and therapeutic applications using this novel paradigm of diagnosing and treating atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This article was funded by a grant from the Fondation Leducq, NIH, HL0888093 and HL086559 (S.T., J.L.W.); the Swiss National Science Foundation PBBSP3-124742 and the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences PASMP3_132566 (G.L.); and NIH GM15431 and GM69338 (J.L.W.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Tsimikas and Witztum are inventors of patents owned by the University of California for the clinical use of oxidation-specific antibodies.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Lichtman AH, Binder CJ, Tsimikas S, Witztum JL. Adaptive immunity in atherogenesis: new insights and therapeutic approaches. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:27–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI63108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145:341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packard RRS, Lichtman AH, Libby P. Innate and adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson GK, Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:204–212. doi: 10.1038/ni.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller YI, Choi SH, Wiesner P, Fang L, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Boullier A, Gonen A, Diehl CJ, Que X, et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity. Circ Res. 2011;108:235–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taleb S, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Adaptive T cell immune responses and atherogenesis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabas I, Williams KJ, Borén J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation. 2007;116:1832–1844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinberg D, Witztum JL. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2311–2316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This comprehensive review describes the history of the development of the concept that oxidation of LDL not only leads to its enhanced uptake by macrophages, but renders it proinflammatory and immunogenic

- 10.Libby P. Counterregulation rules in atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1438–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dijk RA, Kolodgie F, Ravandi A, Leibundgut G, Hu PP, Prasad A, Mahmud E, Dennis E, Curtiss LK, Witztum JL, et al. Differential expression of oxidation-specific epitopes and apolipoprotein(a) in progressing and ruptured human coronary and carotid atherosclerotic lesions. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2773–2790. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P030890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study provides a comprehensive survey of the presence of OSE in various stages of human coronary artery and carotid lesions

- 12.Lee S, Birukov KG, Romanoski CE, Springstead JR, Lusis AJ, Berliner JA. Role of phospholipid oxidation products in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;111:778–799. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartvigsen K, Chou MY, Hansen LF, Shaw PX, Tsimikas S, Binder CJ, Witztum JL. The role of innate immunity in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S388–S393. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800100-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quehenberger O. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis Molecular mechanisms regulating monocyte recruitment in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1582–1590. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500008-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan ZQ, Hansson GK. Innate immunity, macrophage activation, and atherosclerosis. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:187–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorp E, Subramanian M, Tabas I. The role of macrophages and dendritic cells in the clearance of apoptotic cells in advanced atherosclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2515–2518. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabas I. Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spann NJ, Garmire LX, McDonald JG, Myers DS, Milne SB, Shibata N, Reichart D, Fox JN, Shaked I, Heudobler D, et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 2012;151:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study demonstrates that cholesterol loading of macrophages does not lead to an enhanced inflammatory state per se, that accumulation of desmosterol is a key regulator of an anti-inflammatory response in foam cells, and that other external stimuli mediate proinflammatory responses

- 19.Plüddemann A, Neyen C, Gordon S. Macrophage scavenger receptors and host-derived ligands. Methods. 2007;43:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witztum JL. You are right too! J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2072–2075. doi: 10.1172/JCI26130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore KJ, Kunjathoor VV, Koehn SL, Manning JJ, Tseng AA, Silver JM, McKee M, Freeman MW. Loss of receptor-mediated lipid uptake via scavenger receptor A or CD36 pathways does not ameliorate atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2192–2201. doi: 10.1172/JCI24061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erridge C. The roles of toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis. J Innate Immun. 2009;1:340–349. doi: 10.1159/000191413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtiss LK, Tobias PS. Emerging role of Toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S340–S345. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800056-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullick AE, Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Modulation of atherosclerosis in mice by Toll-like receptor 2. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3149–3156. doi: 10.1172/JCI25482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtiss LK, Black AS, Bonnet DJ, Tobias PS. Atherosclerosis induced by endogenous and exogenous toll-like receptor (TLR)1 or TLR6 agonists. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2126–2132. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M028431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadl A, Meher AK, Sharma PR, Lee MY, Doran AC, Johnstone SR, Elliott MR, Gruber F, Han J, Chen W, et al. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ Res. 2010;107:737–746. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Excellent study that demonstrates that oxidized phospholipids can cause a unique proinflammatory phenotype in macrophages

- 27.Kadl A, Sharma PR, Chen W, Agrawal R, Meher AK, Rudraiah S, Grubbs N, Sharma R, Leitinger N. Oxidized phospholipid-induced inflammation is mediated by Toll-like receptor 2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1903–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michelsen KS, Wong MH, Shah PK, Zhang W, Yano J, Doherty TM, Akira S, Rajavashisth TB, Arditi M. Lack of Toll-like receptor 4 or myeloid differentiation factor 88 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10679–10684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403249101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Björkbacka H, Kunjathoor VV, Moore KJ, Koehn S, Ordija CM, Lee MA, Means T, Halmen K, Luster AD, Golenbock DT, et al. Reduced atherosclerosis in MyD88-null mice links elevated serum cholesterol levels to activation of innate immunity signaling pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:416–421. doi: 10.1038/nm1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piya MK, Harte AL, McTernan PG. Metabolic endotoxaemia: is it more than just a gut feeling? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:78–85. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32835b4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller YI, Viriyakosol S, Worrall DS, Boullier A, Butler S, Witztum JL. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent and -independent cytokine secretion induced by minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1213–1219. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159891.73193.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study identifies that an early form of modified LDL can mediate proatherogenic changes in macrophages through TLR4 dependent and independent pathways. Importantly, it suggests that there are endogenous ligands that can activate TLR4 dependent pathways

- 32.Choi SH, Harkewicz R, Lee JH, Boullier A, Almazan F, Li AC, Witztum JL, Bae YS, Miller YI. Lipoprotein accumulation in macrophages via toll-like receptor-4-dependent fluid phase uptake. Circ Res. 2009;104:1355–1363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiesner P, Choi SH, Almazan F, Benner C, Huang W, Diehl CJ, Gonen A, Butler S, Witztum JL, Glass CK, et al. Low doses of lipopolysaccharide and minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein cooperatively activate macrophages via nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein-1: possible mechanism for acceleration of atherosclerosis by subclinical endotoxemia. Circ Res. 2010;107:56–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weismann D, Hartvigsen K, Lauer N, Bennett KL, Scholl HPN, Charbel Issa P, Cano M, Brandstätter H, Tsimikas S, Skerka C, et al. Complement factor H binds malondialdehyde epitopes and protects from oxidative stress. Nature. 2011;478:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nature10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study demonstrates for the first time that CFH is a major MDA binding protein in plasma and explains the association of single nucleotide polymorphisms, that were shown in this study to have diminished ability to bind MDA, with age related macular degeneration. It thus adds to the growing body of literature that OSE are a major target of innate effector proteins, not just in atherosclerosis but also in other OSE-mediated diseases

- 35.Oksjoki R, Jarva H, Kovanen PT, Laine P, Meri S, Pentikäinen MO. Association between complement factor H and proteoglycans in early human coronary atherosclerotic lesions: implications for local regulation of complement activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:630–636. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000057808.91263.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang MK, Binder CJ, Torzewski M, Witztum JL. C-reactive protein binds to both oxidized LDL and apoptotic cells through recognition of a common ligand: phosphorylcholine of oxidized phospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13043–13048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192399699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou MY, Fogelstrand L, Hartvigsen K, Hansen LF, Woelkers D, Shaw PX, Choi J, Perkmann T, Bäckhed F, Miller YI, et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are dominant targets of innate natural antibodies in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1335–1349. doi: 10.1172/JCI36800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper demonstrates that OSE are a major target of innate natural antibodies and that up to 30% of all IgM in plasma of mice and newborn humans bind to such epitopes

- 38.Binder CJ, Horkko S, Dewan A, Chang MK, Kieu EP, Goodyear CS, Shaw PX, Palinski W, Witztum JL, Silverman GJ. Pneumococcal vaccination decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation: molecular mimicry between Streptococcus pneumoniae and oxidized LDL. Nat Med. 2003;9:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nm876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper demonstrates the important concept that innate immune receptors often bind to immunologically similar epitopes present on both endogenous as well as exogenous microbial pathogens and points to a strong role of natural antibodies in protecting against atherosclerosis

- 39.Lewis MJ, Malik TH, Ehrenstein MR, Boyle JJ, Botto M, Haskard DO. Immunoglobulin M is required for protection against atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2009;120:417–426. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.868158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper showed that LDL receptor negative mice that were unable to secrete IgM had a marked increase in atherosclerosis

- 40.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis.The road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergmark C, Dewan A, Orsoni A, Merki E, Miller ER, Shin MJ, Binder CJ, Horkko S, Krauss RM, Chapman MJ, et al. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2230–2239. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800174-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study showed for the first time that Lp(a), as opposed to other lipoproteins, preferentially binds oxidized phosphocholine containing phospholipids

- 42.Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, Borén J, Andreotti F, Watts GF, Ginsberg H, Amarenco P, Catapano A, Descamps OS, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2844–2853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolski B, Tsimikas S. Emerging therapeutic agents to lower lipoprotein (a) levels. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23:560–568. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283598d81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taleb A, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S. Oxidized phospholipids on apoB-100-containing lipoproteins: a biomarker predicting cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular events. Biomark Med. 2011;5:673–694. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsimikas S, Willeit P, Willeit J, Santer P, Mayr M, Xu Q, Mayr A, Witztum JL, Kiechl S. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, prospective 15-year cardiovascular and stroke outcomes, and net reclassification of cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2218–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This epidemiological study shows that the OxPL/apoB measurement can prospectively predict both CVD and stroke outcomes over a 15-year interval and, in association with IgG and IgM autoantibodies to OSE, allows reclassification of a significant (∼30%) of subjects into higher or lower risk categories

- 46.Leibundgut G, Arai K, Orsoni A, Yin H, Scipione C, Miller ER, Koschinsky ML, Chapman MJ, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S. Oxidized phospholipids are present on plasminogen, affect fibrinolysis, and increase following acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1426–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study shows for the first time that OxPL present on plasminogen of humans potentiates fibrinolysis, suggesting a novel mechanism through which plasminogen affects clot formation

- 47.Briley-Saebo KC, Cho YS, Shaw PX, Ryu SK, Mani V, Dickson S, Izadmehr E, Green S, Fayad ZA, Tsimikas S. Targeted iron oxide particles for in vivo magnetic resonance detection of atherosclerotic lesions with antibodies directed to oxidation-specific epitopes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.023. See annotation to Ref. [49••] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briley-Saebo KC, Cho YS, Tsimikas S. Imaging of oxidation-specific epitopes in atherosclerosis and macrophage-rich vulnerable plaques. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2011;4:4–16. doi: 10.1007/s12410-010-9060-6. See annotation to Ref. [49••] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Briley-Saebo KC, Nguyen TH, Saeboe AM, Cho YS, Ryu SK, Volkava E, Dickson S, Leibundgut G, Weisner P, Green S, et al. In vivo detection of oxidation-specific epitopes in atherosclerotic lesions using biocompatible manganese molecular magnetic imaging probes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This study along with Refs. [47,48] demonstrates the feasibility of using murine and human antibodies directed to OSE to enable live imaging of macrophage-rich atherosclerotic plaques and in particular demonstrate that this can be accomplished using MRI techniques

- 50.Amir S, Binder CJ. Experimental immunotherapeutic approaches for atherosclerosis. Clin Immunol. 2010;134:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Binder CJ, Hartvigsen K, Chang MK, Miller M, Broide D, Palinski W, Curtiss LK, Corr M, Witztum JL. IL-5 links adaptive and natural immunity specific for epitopes of oxidized LDL and protects from atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:427–437. doi: 10.1172/JCI20479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kyaw T, Tay C, Krishnamurthi S, Kanellakis P, Agrotis A, Tipping P, Bobik A, Toh BH. B1a B lymphocytes are atheroprotective by secreting natural IgM that increases IgM deposits and reduces necrotic cores in atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2011;109:830–840. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravandi A, Boekholdt SM, Mallat Z, Talmud PJ, Kastelein JJP, Wareham NJ, Miller ER, Benessiano J, Tedgui A, Witztum JL, et al. Relationship of IgG and IgM autoantibodies and immune complexes to oxidized LDL with markers of oxidation and inflammation and cardiovascular events: results from the EPIC-Norfolk Study. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1829–1836. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M015776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Faria-Neto JR, Chyu KY, Li X, Dimayuga PC, Ferreira C, Yano J, Cercek B, Shah PK. Passive immunization with monoclonal IgM antibodies against phosphorylcholine reduces accelerated vein graft atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schiopu A, Bengtsson J, Söderberg I, Janciauskiene S, Lindgren S, Ares MPS, Shah PK, Carlsson R, Nilsson J, Fredrikson GN. Recombinant human antibodies against aldehyde-modified apolipoprotein B-100 peptide sequences inhibit atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2047–2052. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143162.56057.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schiopu A, Frendéus B, Jansson B, Söderberg I, Ljungcrantz I, Araya Z, Shah PK, Carlsson R, Nilsson J, Fredrikson GN. Recombinant antibodies to an oxidized low-density lipoprotein epitope induce rapid regression of atherosclerosis in apobec-1(–/–)/low-density lipoprotein receptor(–/–) mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2313–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ström A, Fredrikson GN, Schiopu A, Ljungcrantz I, Söderberg I, Jansson B, Carlsson R, Hultgårdh-Nilsson A, Nilsson J. Inhibition of injury-induced arterial remodelling and carotid atherosclerosis by recombinant human antibodies against aldehyde-modified apoB-100. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shaw PX, Hörkkö S, Tsimikas S, Chang MK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Chen PP, Witztum JL. Human-derived anti-oxidized LDL autoantibody blocks uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages and localizes to atherosclerotic lesions in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1333–1339. doi: 10.1161/hq0801.093587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsimikas S, Miyanohara A, Hartvigsen K, Merki E, Shaw PX, Chou MY, Pattison J, Torzewski M, Sollors J, Friedmann T, et al. Human oxidation-specific antibodies reduce foam cell formation and atherosclerosis progression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1715–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper both demonstrates that recombinant human OSE antibodies can provide atheroprotection when used to provide passive immunity in murine models of atherosclerosis

- 60.Fang L, Green SR, Baek JS, Lee SH, Ellett F, Deer E, Lieschke GJ, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Miller YI. In vivo visualization and attenuation of oxidized lipid accumulation in hypercholesterolemic zebrafish. J Clin Invest. 2011 doi: 10.1172/JCI57755. http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI57755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Palinski W, Miller E, Witztum JL. Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:821–825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Binder CJ, Shaw PX, Chang MK, Boullier A, Hartvigsen K, Hörkkö S, Miller YI, Woelkers DA, Corr M, Witztum JL. The role of natural antibodies in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1353–1363. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500005-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nilsson J, Björkbacka H, Fredrikson GN. Apolipoprotein B100 autoimmunity and atherosclerosis – disease mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23:422–428. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328356ec7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amir S, Hartvigsen K, Gonen A, Leibundgut G, Que X, Jensen-Jarolim E, Wagner O, Tsimikas S, Witztum JL, Binder CJ. Peptide mimotopes of malondialdehyde epitopes for clinical applications in cardiovascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:1316–1326. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M025445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hermansson A, Ketelhuth DFJ, Strodthoff D, Wurm M, Hansson EM, Nicoletti A, Paulsson-Berne G, Hansson GK. Inhibition of T cell response to native low-density lipoprotein reduces atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1081–1093. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hermansson A, Johansson DK, Ketelhuth DFJ, Andersson J, Zhou X, Hansson GK. Immunotherapy with tolerogenic apolipoprotein B-100-loaded dendritic cells attenuates atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation. 2011;123:1083–1091. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herbin O, Ait-Oufella H, Yu W, Fredrikson GN, Aubier B, Perez N, Barateau V, Nilsson J, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Regulatory T-cell response to apolipoprotein B100-derived peptides reduces the development and progression of atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:605–612. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This paper and Refs. [65,66] provide evidence that there is an adaptive immune response to epitopes of apoB-100 and that induction of tolerance to this can be atheroprotective

- 68.Kiechl S, Willeit J, Mayr M, Viehweider B, Oberhollenzer M, Kronenberg F, Wiedermann CJ, Oberthaler S, Xu Q, Witztum JL, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein(a), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity, and 10-year cardiovascular outcomes: prospective results from the Bruneck study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1788–1795. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsimikas S, Mallat Z, Talmud PJ, Kastelein JJP, Wareham NJ, Sandhu MS, Miller ER, Benessiano J, Tedgui A, Witztum JL, et al. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, lipoprotein(a), and risk of fatal and nonfatal coronary events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:946–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murphy JE, Tedbury PR, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Walker JH, Ponnambalam S. Biochemistry and cell biology of mammalian scavenger receptors. Atherosclerosis. 2005;182:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shishido SN, Varahan S, Yuan K, Li X, Fleming SD. Humoral innate immune response and disease. Clin Immunol. 2012;144:142–158. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weismann D, Binder CJ. The innate immune response to products of phospholipid peroxidation. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;1818:2465–2475. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]