Abstract

Background:

We have recently identified miR-125b upregulation in glioblastoma (GMB). The aim of this study is to determine the correlation between miR-125b expression and malignant grades of glioma and the genes targeted by miR-125b.

Methods:

Real-time PCR was employed to measure the expression level of miR-125b. Cell viability was evaluated by cell growth and colony formation in soft-agar assays. Cell apoptosis was determined by Hoechst 33342 staining and AnnexinV-FITC assay. The Luciferase assay was used to confirm the actual binding sites of p38MAPK mRNA. Western blot was used to detect the gene expression level.

Results:

The expression level of miR-125b is positively correlated with the malignant grade of glioma. Ectopic expression of miR-125b promotes the proliferation of GMB cells. Knockdown of endogenous miR-125b inhibits cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis. Further studies reveal that p53 is regulated by miR-125b. However, downregulation of the endogenous miR-125b also results in p53-independent apoptotic pathway leading to apoptosis in p53 mutated U251 cells and p53 knockdown U87 cells. Moreover, p38MAPK is also regulated by miR-125b and downregulation of miR-125b activates the p38MAPK-induced mitochondria apoptotic pathway.

Conclusion:

High-level expression of miR-125b is associated with poor outcomes of GMB. MiR-125b may have an oncogenic role in GMB cells by promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis.

Keywords: microRNA, miR-125b, glioblastoma, cell apoptosis, p53, p38MAPK

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) serve as the master regulators of gene expression. MiRNAs regulate gene expression in a sequence-specific fashion, which bind to 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs and then affect the translation and/or mRNA stability. Tumour analysis from the same tissue by miRNA profile has exhibited significantly distinct miRNA signatures compared with normal cells (Calin and Croce, 2006; Iorio et al, 2007). The abnormal levels of miRNAs in tumours have important pathogenetic consequences (Olson et al, 2009). Some miRNAs, acting as oncogenes, promote tumour aggravation by downregulation of tumour suppressors (Hammond, 2007). For example, the miR-17-miR-92 cluster in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia reduces the level of the transcription factor E2F1 (Nagel et al, 2009; Nicoloso et al, 2009); miR-21 downregulates the tumour inhibiting factor PTEN in lung cancer cells; and miR-125b is an important repressor of p53 and inhibits p53-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells (Hyun et al, 2009). On the other hand, tumours that lose miRNAs generally result in overexpression of oncogenes; the let-7 family miRNAs are frequently downregulated in cancers and result in overexpression of Ras and Myc oncogenes (Johnson et al, 2005; Kim et al, 2009); miR-15 and miR-16 negatively regulate BCL-2 and are frequently inactivated in leukaemia (Cimmino et al, 2005). Our recent study also showed that the expression of miR-26b is decreased in glioblastoma (GMB) and enforced expression of miR-26b inhibits the proliferation and invasion of GMB cells by negatively regulating EPHA2 expression (Wu et al, 2011).

MiR-125b, a homologue of lin-4, is an important regulator of developmental timing in C. elegans (Lee et al, 2005). MiR-125b is highly expression in mouse brain and has been implicated in neuronal differentiation of mouse P19 cells by targeting the RNA-binding protein Lin-28 (Wu and Belasco, 2005). In human cancer cells, miR-125b promotes neuronal differentiation by suppressing multiple targets (Le et al, 2009a). MiR-125b is also found to be expressed in solid tumours and associated with cell proliferation and survival (Le et al, 2009b; Xia et al, 2009; Klusmann et al, 2010; Shi et al, 2010; Zhou et al, 2010). However, the role of miR-125b in the proliferation and apoptosis of GMB cells has not been well documented. Recent studies have found that overexpression of miR-125b suppresses ATRA-induced apoptosis in human GMB cells and low expression of miR-125b enhances the sensitivity of cells to ATRA-induced apoptosis by targeting Bmf mRNA translation (Xia et al, 2009). It has also been reported that miR-125b functions as an apoptotic inhibitor via negative regulation of p53 in zebrafish and human neuroblastoma cells (Le et al, 2009b). Moreover, recent studies have shown that miR-125b directly represses many targets in the p53 network, including both apoptosis regulators and cell-cycle regulators, such as Bak1, Bcl-2 and cyclin C (Zhou et al, 2010; Guan et al, 2011; Le et al, 2011; Shi et al, 2011), suggesting that miR-125b regulates cell apoptosis via the p53-dependent pathway. However, there is some evidence that p53 is not regulated by miR-125b. For example, overexpression of miR-125b couldn't alter the expression of p53 in mouse Ba/F3 cells and knockdown of miR-125b didn't lead to any alterations of the expression level in p53 or its target gene p21 in human REH cells (Gefen et al, 2010). In the present studies, we investigated the correlation of the expression level of miR-125b and the malignant grade of glioma and the effect of miR-125 on the sensitivity of temozolomide (TMZ) to GMB cells. We demonstrate that knockdown of miR-125b activates the p53 and p38MAPK apoptosis signal pathways. However, the cell apoptosis induced by lacking miR-125b is not affected by the knockdown of p53 and p38MAPK, indicating that miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis is through p53 and p38 MAPK-independent pathways in GMB cells.

Material and Methods

Cell lines and normal brain and tumour tissues

Human HEK-293T cells, human GMB U251 and U87 cells and rat GMB C6 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured according to the recommended protocols. Patient samples including glioma and normal brain tissues were obtained from the Brain Institute, Qingdao Medical University affiliated Hospital (Qingdao, China) after informed consent and approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao Medical University, China. Samples (48) were used for this study including 9 primary grade pilocytic astrocytomas (WHO I), 10 grade II astrocytoma (WHO II), 9 grade III anaplastic astrocytomas (WHO III), 13 grade IV GMB Multiforme (WHO IV) and 7 normal brain tissues derived from the temporal lobes and saddle area of the patients with arachnoid cyst (AC) or brain trauma after surgery. The patient information and clinical data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Total number | 48 |

|---|---|

|

Gender | |

| Male | 28 |

| Female |

20 |

|

Age | |

| Median age (range) |

42 (9–77) years |

|

Grade | |

| Normal brain | 7 |

| WHO I | 9 |

| WHO II | 10 |

| WHO III | 9 |

| WHO IV |

13 |

|

Recurrence | |

| Yes | 8 |

| No | 40 |

Real-time quantitative RT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen tissue samples or cultured cells using the TRIzol kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Stem-loop RT–PCR (P/N: 000449; TaqMan MicroRNA Assays; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to quantitate miR-125b according to the manufacturer's instructions. TaqMan probes and primers for p38MAPK were obtained from Applied Biosystems (P/N: Hs01047706_m1; Applied Biosystems) and the PCR reaction condition followed the manufacturer's protocol.

All reactions were performed in duplicate and a negative-control lacking cDNA was included. U6 snRNA (P/N: 001973; Applied Biosystems) and GAPDH (P/N: Hs02758991_g1; Applied Biosystems) were used as internal controls, respectively, to analyse the expression of miR-125b and p38MAPK. The relative expression level of miR-125b and p38MAPK was calculated using the delta–delta Ct methods.

Synthesis of luciferase reporters and the p53 shRNA expression vector

The 3′-UTR of human p53 and p38MAPK was amplified using the total cDNA of U87 cells as the template and then inserted into the psiCheck2 vector to synthesise the luciferase reporter constructs, Luc+wt p53 3′-UTR and Luc+wt p38MAPK 3′-UTR, respectively. The sense and antisense sequences of the MRE were synthesised, annealed and linked into the psiCheck2 vector to construct miR-125b MRE luciferase reporter Luc+miR-125b MRE. The construct Luc+125b mutated MRE, which introduced some mutations in the seed region of miR-125b MRE, was synthesised by ligating the mutation MRE fragment of miR-125b into the psiCheck2 vector as described previously (Le et al, 2009b). pSilencer4.1-CMV/neo vector (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to construct the p53 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression vector. Gene-specific shRNAs targeting p53 were ligated the downstream of the CMV promoter. The sequences of shRNA p53 are as follows: Forward: 5′-GACTCCAGTGGTAATCCTAC-3′ reversal: 5′-GTAGGATTACCACTGGAGTCTT-3′.

The forward and reverse synthetic oligonucleotides were annealed and inserted into the HindIII and BamHI sites of the pSilencer4.1-CMV/neo vector to construct the p53 shRNA expression vectors, pSilencer-p53.

Transfection and drug treatments

The two miRNA mimics used in the experiments were purchased from Dharmacon (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). One of the microRNA mimics is microRNA duplex (NC-DP, MIMAT0000039) as negative control and another is 125b-DP, which is a duplex of miR-125b (MIMAT0000423). The antisense of two microRNAs, negative antisense of negative control microRNA (NC-AS) and miR-125b antisense (125b-AS) were also purchased from Dharmacon. MiRNA duplexes and antisense oligonucleotides were transfected at a final concentration of 50 and 100 nM, respectively. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used as the transfection reagent following the manufacturer's protocol. The expression level of miR-125b was analysed by real-time RT–PCR. Luciferase reporter constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells at a final concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1. To construct p53 knock-down cell line U87(p53 KD), pSilencer-p53 plasmid was transfected into U87 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and U87(p53 KD) cell line was established by continuous selection with G418 (Invitrogen). Temozolomide (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich). U87 Cells with or without miRNAs were treated with TMZ in certain concentrations. After being cultured for 6 h, cells were collected and washed with drug-free medium and allowed to grow for another 24 h. Then, cells were collected to determine the viability and apoptosis using morphological analysis or MTT assay.

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter construct was co-transfected with 50 nM l−1 of miRNA duplexes or 100 nM l−1 miRNA antisenses into HEK-293 T cells in a 24-well plate Lipofectamin-2000 (Invitrogen). After incubation for 48 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1000 g for 10 min and lysed using lysis buffer. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined using the Dual-Luciferase reporter system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol.

MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bro-121 mide) assay

C6, U251, U87 and U87 (p53-) cells were plated onto 96-well plates with 5 × 103 cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight. The cells were transfected with 125b-DP at the final concentration of 50 nM l−1 or 125b-AS at the final concentration of 100 nM l−1 using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). After incubation for 48 h, MTT dye (30 μl, 5 mg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich) was added into the culture medium. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, the MTT solution was removed and 150 μl DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The OD value at 490 nm was measured by Multiskan EX microplate photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MS, USA).

Colony formation in Soft-agar

U87 cells were treated with olionucleodies for 24 h and the cells were harvested by trypsinisation, and diluted to a density of 2000 cells per ml. The cells were collected and suspended in 1 ml of 0.3% melted agar in DMEM with 10% FBS and plated in 60-mm dishes overlayed with 0.6% agar in the same medium. Medium was changed every 3 days. After being cultured for 7 days, colonies containing at least 50 cells were counted and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich).

Apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was detected by Hoechst 33342 staining, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated nick-end labelling (TUNEL) assay and Annexin V-FITC assay. For Hoechst 33342 staining, cells were transfected with oligonucleotides or treated with drugs and washed with PBS twice, fixed with 70% ethanol for 30 min at room temperature and then stained with Hoechst 33342 (1 μg ml−1) for 5 min. Chromatin fluorescence was observed under a UV-light microscope, and apoptotic cells were morphologically defined by cytoplasmic and nuclear shrinkage and chromatin condensation (Zhu et al, 2006). For TUNEL assay, cells were cultured on L-polylysine coated slides and oligonucleotides were transfected into cells. After treatment, the cells on the slides were fixed and analysed using the DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Apoptotic cell death was quantified by flow cytometry with Annexin V-FITC and PI staining. Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, both attached and floating cells were collected and resuspended in binding buffer before adding the Annexin V-FITC antibody and propidium iodide. Stained cells were analysed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

UV irradiation

The UV irradiation experiment was performed as previously described (Zhao et al, 2012). Briefly, cells were transfected with 125b-DP, NC-DP or 125b-AS at the final concentration of 100 nM l−1. After being cultured for 12 h, cells were washed with PBS and irradiated with 15 J m−2 UVC for 4 h and then supplemented with fresh medium.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Solaibo, Beijing, China). Proteins were separated by a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a methanol-activated PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The membrane was blocked in blocking solution (5% nonfat dry milk powder) for 2 h at room temperature and subsequently probed with primary antibodies; including p53, p21, Bax, Bcl-2, Caspaese-3. Caspase-9, p38MAPK or β-actin; (used at a 1/1000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After three 10 min washes with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS buffer, membranes were incubated with rabbit anti mouse or goat anti rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) for 1 h. After an additional three 10 min washes with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS buffer, the chemiluminescence method was employed to detect the signals using Super Signal West Dura (Thermo Scientific) and protein bands were visualised by autoradiography. Quantitation of signal intensities was performed using densitometry on a Hewlett-Packard ScanJet 5370C (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with NIH image 1.62 software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of the data were analysed by the two-tail Student's t-test with a minimum significance level set at P<0.05 (marked as *P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

Results

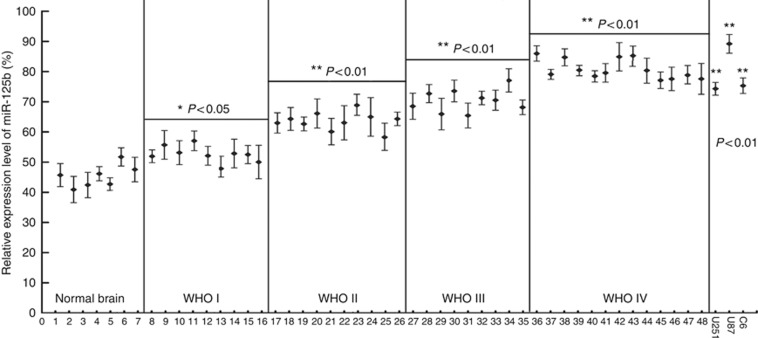

MiR-125b positively correlates with the aggression of glioma

The expression of miR-125b in glioma tissues from the patients has not been well documented. In order to determine the relationship between miR-125b expression and malignant grade of glioma, the expression of miR-125b in the glioma tissues from the patients of normal brain and tumours and GMB cells was analysed by real-time stem-loop RT–PCR. The results showed that miR-125b exhibited a relative low-level expression in normal brain tissues, whereas the expression of miR-125b was significantly upregulated in glioma samples (P<0.05 in WHO I and P<0.01 in WHO II–IV). The enhanced expression levels of miR-125b were correlated with increasing grades of glioma (WHO I, WHO II, WHO III and WHO IV, Figure 1). High expression of miR-125b was also found in the three tested GMB cell lines, including rat GMB C6, and human GMB U251 and U87 cells (P<0.01, Figure 1). These results suggest that the expression level of miR-125b is closely associated with glioma progresses and it may become a potential biomarker for the diagnosis of glioma clinically.

Figure 1.

Expression of miR-125b in glioma samples and C6, U87 and U251 cells. The malignant grade of glioma was evaluated according to WHO criteria as described in Materials and Methods. Samples of ID 1–7 were normal brain tissues from patients with noncancerous disease and were used as the controls; ID 8–16 from pilocytic astrocytomas classified to WHO I; ID 17–26 from astrocytoma classified to WHO II; ID 27–35 from anaplastic astrocytomas classified to WHO III; and ID 36–48 from Glioblastoma Multiforme classified to WHO IV. Each sample was divided by a dashed line. Total RNA was isolated from the glioma tissues and glioma cells of C6, U87 and U251 and real-time PCR was performed to analyse the expression of miR-125b as described in Materials and Methods. The relative expression of miR-125b was expressed as the ratio of the expression level miR-125b to that of U6. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, as compared with the control group.

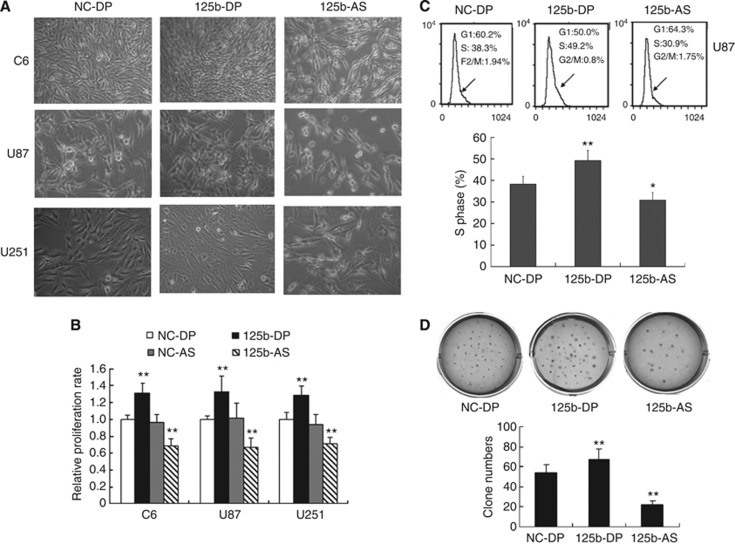

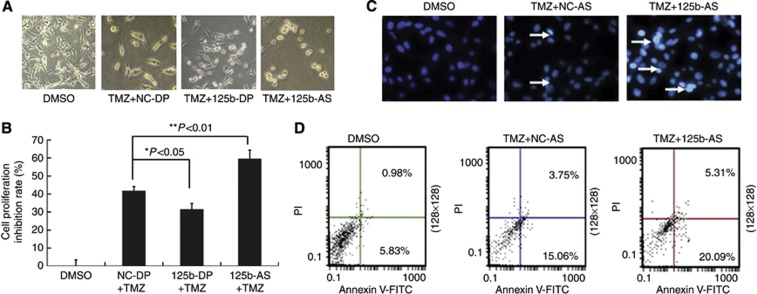

MiR-125b promotes the cell proliferation and survival of GMB cells

We next investigated the effect of miR-125b on the proliferation of GMB cells. MiR-125b duplex (125b-DP) or 2′-omethoxyethy (2′-O-MOE) modified miR-125b anti-sense (125b-AS) were transfected into rat GMB C6 cells and human GMB U87 and U251 cells to upregulate or downregulate the expression of miR-125b, respectively. The miR-125b expression level was detected by quantitative RT–PCR (qRT–PCR) in each cell line. The level of miR-125b was increased about fourfold with transfection of 125b-DP, while it was decreased more than fivefold with transfection of 125b-AS compared with the endogenous miR-125b level (Supplementary Figure 1). These results suggest that both 125b-DP and 125b-AS are effective in modulating the level of miR-125b. We then determined the cell proliferation by morphological changes and MTT assay. As shown in Figure 2A, cell proliferation was promoted by overexpression of miR-125b in all of the three cell lines, including C6, U87 and U251 cells. In contrast, cell proliferation was reduced by knockdown of endogenous miR-125b in C6, U87 and U251 GMB cells (Figure 2A). MTT assay revealed that after treating the cells with 125b-DP, the cell proliferation rate was increased by 31.0%, 35.0% and 28.5% in C6, U87 and U251 cells, respectively (Figure 2C). However, the cell growth was inhibited by 30.6%, 33.4% and 28.7% in C6, U87 and U251 cells, respectively, when the cells were treated with 125b-AS (Figure 2B). As the effect of miR-125b is most significantly on the proliferation of U87 cells, we selected U87 cells for our future studies. Cell-cycle analysis showed that overexpression of miR-125b in U87 cells increased the cell cycle on S phase. In contrast, downregulation of miR-125b caused cell-cycle arrest at G1 phase (Figure 2C). Further study showed that overexpression of miR-125b increased colony formation of U87 cells in soft-agar assay. There were 28.5% increase of colony numbers in cells treated with 125b-DP compared with the cells transfected with NC-DP (Figure 2D). When the endogenous miR-125b was inhibited by 125b-AS, the cell colony number was significantly decreased up to 50% compared with the cells transfected with negative control miRNAs (NC-DP, Figure 2D). To further confirm the effects of miR-125b on GMB cell proliferation, we established a miR-125b stable knock-down U87 cell line as described in Supplementary Method 1. The results showed that the cell proliferation was significantly increased in the miR-125b knock-down U87 cells treated with 125b-DP (Supplementary Figure 2). These results suggest that miR-125b has a key role in the proliferation of GMB cells and it may function as an oncogene in GMB cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of miR-125b on the cell proliferation of glioblastoma. (A) Morphological observation. C6, U87 and U251 cells were treated with NC-DP, 125b-DP or 125b-AS, respectively. After incubation for 48 h, the cell morphology was observed under the microscope. (B) Determination of cell proliferation by MTT assay. C6, U87 and U251 cells were transfected with NC-DP, 125b-DP, 125b-AS or the negative antisense oligonucleotides (NC-AS), respectively. After incubation for 48 h, cell proliferation rates were analysed by MTT assay. The growth rates of cells transfected with NC-DP were defined as 1.0. **P<0.01, as compared with NC-DP group. (C) Cell-cycle assay. U87 cells were transfected with NC-DP or 125b-DP or 125b-AS, respectively. After being cultured for 48 h, cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide and cell cycle was analysed by flow cytometry. Representative analysis of three independent experiments is shown. Statistically significant differences of S phase between the groups of 125b-DP and NC-DP or between 125b-AS and NC-DP group were observed: *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (D) Colony formation assay. U87 cells were transfected with NC-DP or 125b-DP or 125b-AS, respectively. After incubation for 7 days, the colonies formed by the transfected cells were stained with crystal violet and the number of the colonies was counted. The top panel was a representative sample from each group, while low panel indicated the quantitive results of colony formation assay. Statistically significant differences between the groups of 125b-DP and NC-DP or between 125b-AS and NC-DP group were observed: **P<0.01.

MiR-125b has been proposed to regulate both apoptosis and proliferation (Le et al, 2011). We further investigated the role of miR-125b in the apoptosis of GMB cells. NC-DP, 125b-DP or 125b-AS were transfected into U87 cells, respectively. After being cultured for 48 h, cells were collected and Hoechst 33342 staining was performed to detect the apoptosis cells. Cell nuclear pyknosis, chromosome condensation and formation of apoptotic bodies were observed in U87 cells treated with 125b-AS as detected by Hoechst 33342 staining. However, no apoptosis was found in cells transfected with NC-DP or 125b-DP (Figure 3A). TUNEL assay also confirmed the results (Figure 3B). AnnexinV-FITC and PI staining assays were preformed to quantitate the number of apoptotic cells. As showing in Figure 3C, the percentage of early apoptotic cells (AnnexinV-FITC-positive/PI-negative) was significantly increased in cells transfected with 125b-AS. However, overexpression of miR-125b didn't affect the apoptosis of U87 cells (Figure 3B). The results indicate that miR-125b is critical for the survival of GMB cells, in which knockdown of endogenous miR-125b by 125b-AS induces cells apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of miR-125b induces apoptosis in U87 cells. U87 cells were transfected with NC-DP, 125b-DP or 125b-AS, respectively. After incubation for 72 h, cells were fixed and apoptosis was detected by Hoechst 33342 stain, TUNEL and Annexin V-FITC/PI analysis, respectively. (A) Observation of nuclear morphology. Cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and nuclear morphology was observed under a fluorescence microscope. (B) TUNEL analysis of the apoptosis cells. TUNEL analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods and Fluorescence microscope was used to analyse the apoptosis cells. (C) The externalisation of phosphatidylserine during the progression of apoptosis was detected. Early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI−) are in the right lower quadrant. The apoptotic cells are indicated by white arrows.

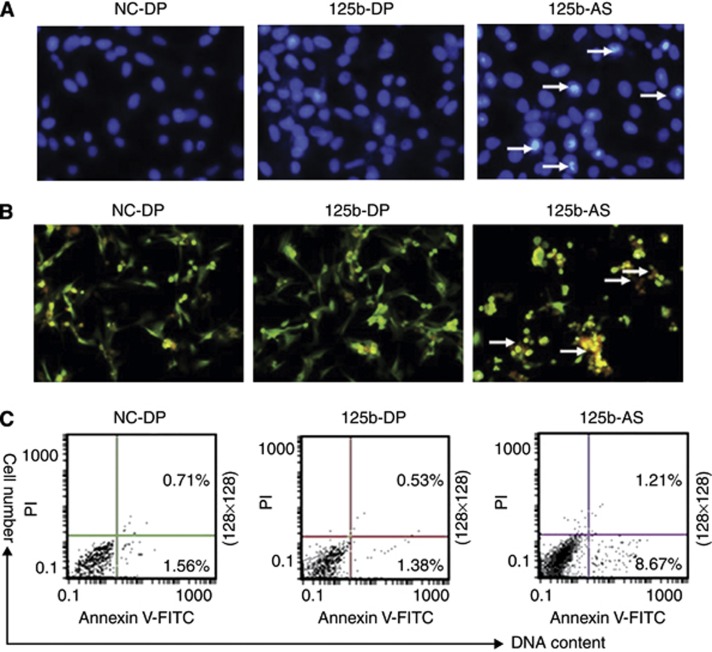

Downregulation of miR-125b increases the sensitivity of GMB cell to temozolomide

Temozolomide (TMZ), a DNA methylating agent with pro-apoptotic activity, is widely used in GMB therapy (Das et al, 2004). We examined whether downregulation of endogenous miR-125b was capable of promoting TMZ-induced apoptosis. U87 cells were transfected with 125b-AS and then treated with TMZ. Cell morphological observation revealed that there were few pieces of debris and fewer dead cells in miR-125b-transfected cells. In contrast, more pieces of debris and more detached cells were observed in the cells treated with 125b-AS (Figure 4A). MTT assay also confirmed that overexpression of miR-125b in U87 cells resulted in cells resistance to TMZ, but downregulation of miR-125b with 125b-AS increased the sensitivity of U87 cells to TMZ (Figure 4B). The inhibitory rate of 125b-AS transfected cells treated with TMZ for 72 h was up to 58.7% that was significantly higher compared with that of TMZ plus NC-DP (41.2%) and TMZ plus 125b-DP (30.8%) treated groups. In addition, the cell numbers of nuclear shrinkage and chromatin condensation were also increased when the cells treated with 125b-AS as determined by Hoechst 33342 staining analysis (Figure 4C). Moreover, Annexin V-FITC and PI staining assay revealed that the apoptotic rate was increased from 18.81 to 25.43% in 125b-AS transfected cells compared with the control (Figure 4D). These results suggest that knockdown of endogenous miR-125b enhances TMZ-induced apoptosis in U87 cells, and miR-125b inhibitor (125b-AS) possesses potential to be developed as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of GMB.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of miR-125b enhances the sensitivity of U87 cells to TMZ. U87 cells were transfected with NC-DP, 125b-DP or 125b-AS, respectively. After incubation for 48 h, the cells were treated with TMZ. (A) Observation of cell morphology. After being treated with TMZ, the cells were incubated for another 24 h and cell morphology was examined under a microscrope. (B) Determination of cell proliferation rate using MTT assay. U87 cells were transfected with oligonucleotides and TMZ were added into the cell culture medium. After being cultured for 24 h, the cell proliferation rates were evaluated by MTT assay. The inhibitory rates of cells were calculated using the formula: (OD value in 0.1% DMSO-treated group−OD value in TMZ and oligonucleotide treated group/OD value in 0.1% DMSO-treated group × 100%. Statistically significant differences between the groups of 125b-DP+TMZ and NC-DP+TMZ or between 125b-AS+TMZ and NC-DP+TMZ group were observed: *P<0.05 (P=0.0216) and **P<0.01 (P=0.0043). (C) Observation of nuclear morphology. Cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and nuclear morphology was observed under a fluorescence microscope. The white arrows show the apoptotic cells with condensed, fragmented nuclei. (D) Quantities of the apoptosis cells with Annexin V-FITC/PI stain and Flow cytometry analysis. Early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI−) are in the right lower quadrant.

Downregulation of miR-125b activates p53 and p53 pathway

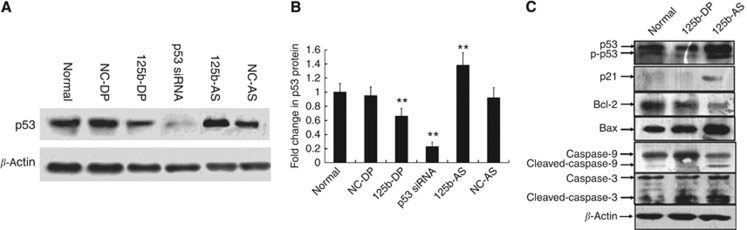

Previous studies have shown that p53 is involved in miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis and proliferation; miR-125b could regulate both human and zebrafish p53 and p53 network related genes (Hyun et al, 2009). During zebrafish embryogenesis, loss of miR-125b leads to widespread apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner (Le et al, 2009b). To examine the possibility of p53 regulation by miR-125b in GMB cells, we overexpressed miR-125b by transfecting 125b-DP into U87 cells. As shown in Figure 5A and B, the p53 expression level was significantly inhibited. In contrast, silencing miR-125b by 125b-AS increased the p53 expression level. NC-DP and NC-AS was transfected as negative control and p53-specific siRNA was used as positive control. Quantitive analysis further confirmed that ectopic expression of miR-125b reduced the level of p53 protein by 40% (P<0.01) in U87 cells (Figure 5B). In addition, the expression of p21 and Bax, the two main targets of p53, was also decreased significantly in cells transfected with 125b-DP (Figure 5C). In contrast, knockdown of miR-125b increased the endogenous p53 protein expression by 35% (Figure 5B) and downregulation of miR-125b also led to activation of the p53-dominant apoptosis pathway. As shown in Figure 5C, treatment of U87 cells with 125b-AS resulted in the reduction of Bcl-2 expression and enhancement of Bax expression. Moreover, the cleavage of procaspase-9 and procaspase-3 was also elevated. These data suggest that p53 is an important target gene of miR-125b, and miR-125b functions as a regulator in the p53-dominant apoptosis pathway.

Figure 5.

The expression of p53 is regulated by miR-125b in glioma cells. (A) miR-125 downregulates p53 expression in U87 cells. U87 cells were transfected with NC-DP, 125b-DP, NC-AS or 125b-AS, respectively. After incubation for 72 h, the expression level of p53 was analysed by western blot as described in Materials and Methods. P53-specific siRNA was used as a positive control. (B) Quantitative results of p53 expression. Quantitation of signal intensities was performed using densitometry on a Hewlett-Packard ScanJet 5370 C. The percentage of p53 is calculated using the formula: the value of densitometry of p53/the value of densitometry β-actin expression (n⩾3) × 100%. The relative p53 expression level in nontransfected U87 cells was defined as 1.0. The relative expression level of p53 siRNA-treated group was used as a positive control. The two-tail Student t-test was employed to statistically analyse the results: **P<0.01. (C) Downregulation of miR-125b activates the p53 and p53 related gene expression dominant cell apoptosis. U87 cells were transfected with NC-DP, 125b-DP or 125b-AS. After incubation for 72 h, cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 r.p.m. for 5 min and cell protein was isolated. The expression level of p53, p21, Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3 and capsase-9 were detected by western blot. The expression of β-actin was used as a loading control.

MiR-125b regulates cell apoptosis independent of p53 in GMB cells

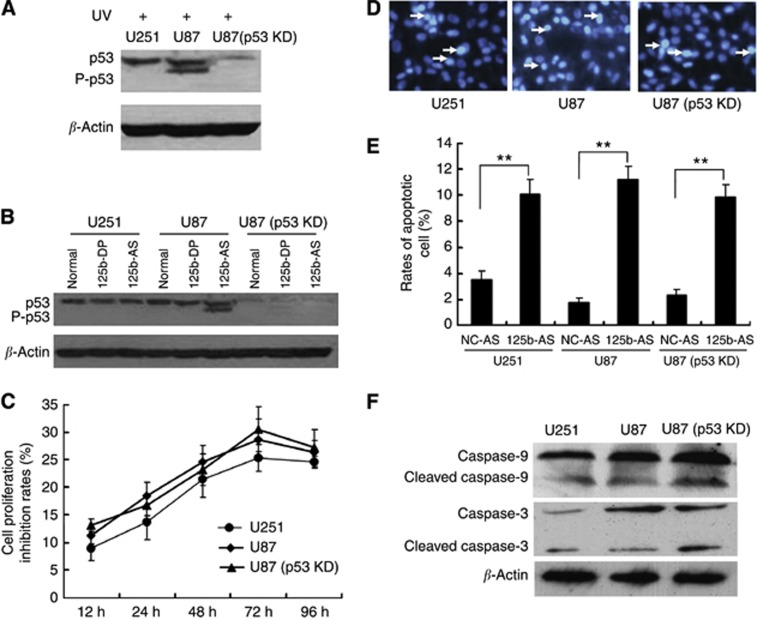

To further elucidate if the proliferation and apoptosis of GMB cells mediated by miR-125b is in a p53-dependent manner or not, we analysed the miR-125b-mediated apoptosis in cells with different p53 levels. We selected three kinds of cells including U251 cells with a mutation on the p53 gene (Godbout et al, 1992) and U87 cells expressing the wild-type p53 (Van Meir et al, 1994) and p53 knock-down with the p53 gene stable knockdown by a p53-specific shRNA expression vector. As shown in Figure 6A, the p53 expression was almost abolished in the U87(p53 KD) cells either with or without UV radiation. UV radiation only increased the phosphorylation of p53 protein in U87 cells with wild-type p53 but not in U251 and U87(p53 KD) cells. In addition, downregulation of miR-125b increased p53 expression levels of total p53 and p53 phosphorylation in U87 cells, but not in the cells with p53 mutation (U251 cells) or p53 silencing U87(p53 KD) cells. Next, we investigated the effects of downregulation of miR-125b on proliferation and apoptosis of the three cells. 125b-AS was transfected into the cells and cells proliferation rates were detected by MTT assay. As shown in Figure 6C, transfection of 125b-AS resulted in inhibition of the cell proliferation in all of the three cells without significant difference (Figure 6C). Cell apoptosis were also observed in all three cells by Hoechst 33342 staining (Figure 6D) and Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry assay (Figure 6E). In addition, the caspase-9 and caspase-3 still be activated by downregulation of miR-125b in U87(p53 KD) cells (Figure 6F). These results reveal that under lacking p53 condition, the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway still can be triggered by reducing miR-125b expression and p53 is not necessary for miR-125b-induced cell apoptosis although it is involved in miR-125b-induced cell apoptotic pathway.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of miR-125b induces cell apoptosis independent on p53 expression. (A) Effect of UV radiation of p53 expression in U251 (p53 mutation) and U87 with p53 wild-type and p53 knock-down [U87(p53KD)] cells. (B) Downregulation of miR-125b activates p53 expression in p53 wild-type U87 cells but not in U251 and U87(p53 KD) cells. (C) Effect of 125b-AS on the proliferation of glioblastoma cell lines. 125b-AS was transfected into cells and the cell proliferation inhibitory rates were evaluated by MTT assay at 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h, respectively. The inhibitory rates of cells were calculated using the formula: the OD value in cells transfected with 125b-AS /to the OD value in cells transfected with NC-AS × 100%. (D) Observation of nuclear morphology. Cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and nuclear morphology was observed under a fluorescence microscope. The white arrows showed the apoptosis cells with condensed, fragmented nuclei. (E) Quantities for the apoptosis cells with Annexin V-FITC/PI stain and Flow cytometry analysis. U251, U87 and U87(p53 KD) cells were transfected with NC-AS or 125b-AS. After incubation for 72 h, the cell apoptosis rates were detected by Annexin V-FITC/ PI stain and Flow cytometer analysis. The two-tail Student's t-test was employed to statistically analyse the results: **P<0.01. (F) Effect of 12b-AS on caspases expression in U251, U87 and U87(p53 KD) cells. Cells were treated with 125b-AS. After incubation for 72 h, cells were collected and the expression of caspase-9, cleaved caspase-9, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 were detected by western blot. The expression of β-actin was used as a loading control.

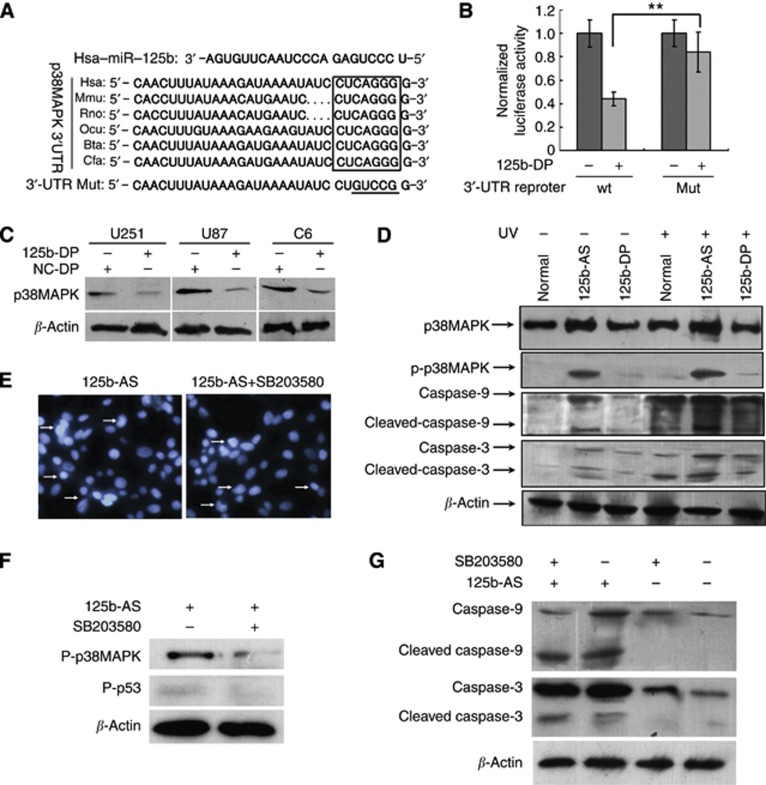

P38 MAPK is regulated by miR-125b

As p38 MAPK has an important role in apoptotic pathway, we then investigated if miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis is associated with p38MAPK pathway or not. Here we detected the expression of p38MAPK in normal tissues of brain, glioma samples with different grades (WHO I–IV), and three glioma cell lines. Indeed, we found that expression of p38MAPK was significantly decreased in the malignant glioma, including anaplastic astrocytoma and GMB (P<0.01), accompanying the increase of miR-125b (Supplementary Figure 3A). We also confirmed that the expression level of p38MAPK was decreased in high malignant grade of glioma tissues by immunohistochemistry study as described in Supplementary Method 2. The results suggested that high level of miR-125b in malignant glioma results in the decreased expression of p38MAPK (Supplementary Figure 3B). Then we tried to identify the miR-125b-binding sites through the p38MAPK mRNA. We found a conserved binding site (miRNA response elements, MREs) in 3′-UTR of p38MAPK via TargetScan analysis (Figure 7A). Ectopic expression of miR-125b suppressed the activity of Luciferase activity in HEK-293T cells co-transfected with 125b-DP and the construct containing the entire 3′-UTR of human p38MAPK (Figure 7B). Next, we investigated if the p38MAPK expression could be regulated by miR-125b. 125b-DP was transfected into U251, U87 and C6 cells, and the results showed that overexpression of miR-125b significantly inhibited the p38MAPK expression (Figure 7C). To further confirm the role of miR-125b on p38MAPK expression, UVC radiation was performed to determine the p38MAPK expression in cells with different level of miR-125b. As shown in Figure 7D, the expression of p38MAPK was increased significantly in U87 cells treated with 125-AS either with or without UVC radiation. However, no expression increase of p38MAPK was found in cells transfected with 125-DP when the cells were irradiated with UVC. The results indicate that p38MAPK could be regulated by the miR-125b in U87 cells (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Knockdown of miR-125b induces apoptosis in glioblastoma cells independent of p38MAPK. (A) The predicted miR-125b-binding site in the 3′-UTR of p38MAPK. The miR-125b seed sequences and their predicted binding sites in the 3′-UTR of p38MAPK 3′-UTR shown in frame. The underlined sequences represented the mutation seed sequence of miR-125b in 3′-UTR of p38MAPK. (B) miR-125b targets the 3′-UTR of p38MAPK in luciferase reporter assay. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with 125b-DP and p38MAPK full-length 3′-UTR-luciferase reporter or p38MAPK 3′-UTR mutation luciferase reporter, respectively. After incubation for 48 h, luciferase assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods to determine the expression of p38MAPK. (C) Overexpression of miR-125b downregulates p38MAPK expression in U251, U87 and C6 cells. NC-DP and 125b-DP were transfected into U87, U251 and C6 cells and the level of p38MAPK was analysed by western blot. (D) p38MAPK is activated by knock-down of miR-125b in U87 cells. 125b-AS or 125b-DP was transfected into U87(p53 KD) cells, and treated with or without UV radiation. After being cultured for 48 h, the cells were collected and total cell proteins were isolated. The total expression of p38MAPK and phosphorylation p38MAPK (P-p38MAPK) were detected by western blot. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (E) Cell apoptotic determination with Hoechst 33342 stain in U87(p53 KD) cells transfected with 125b-AS treated with or without SB203580. U87(p53 KD) cells were transfected with 125b-AS, after incubation for 24 h, p38MAPK-specific inhibitor was added. After incubation for another 48 h, the apoptotic cells were stained by Hoechst 33342 as showed by arrows. (F) The expression of p-p38MAPK and p-p53 in U87(p53 KD) cells transfected with 125b-AS treated with or without SB203580 was determined by western blot. After incubation for 24 h, cells were treated with or without p38MAPK-specific inhibitor, SB203580. After being cultured for another 24 h, cells were collected and nuclear protein was isolated. Western blot was performed to detect the expression of p-p38MAPK and p-p53. (G) Caspases 9 and 3 expression in U87(p53 KD) cells after being transfected with 125b-AS and treated with or without SB203580. Cell treatment was described as above and the expression of caspase-9, cleaved caspase-9, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 were detected by western blot. The expression of β-actin was used as a loading control.

To document whether the regulation of apoptosis by miR-125b in GMB cells is a p38MAPK-dependent manner or not, we studied the effects of 125b-AS on p38MAPK expression in U87 (p53 KD) cells with or without the treatment of SB203580, a p38MAPK-specific inhibitor. As shown in Figure 7E, a similar amount of apoptosis was found in the cells either treated with or without SB203580, suggesting that p38MAPK is not necessary for miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis. We then studied the effect of miR-125b on apoptosis in U87 (p53 KD) cells after SB203580 treatment. Both p53 and p38MAPK were nearly completely inhibited in U87(p53 KD) cells after SB203580 treatment (Figure 7F), while the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 still occurred when the cells were treated with 125b-AS (Figure 7G). These results suggest that both p53 and p38MAPK pathways are involved but not necessary in miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis.

Discussion

Upregulation of miR-125b has been found in most GMB tissues (Sempere et al, 2004), but the relationship of miR-125b expression and the malignant grade of glioma has not been well documented. In the present study, we found that the expression level of miR-125b was positively correlated with the malignancy of glioma. The expression level of miR-125b was increased with higher glioma grade, suggesting the potential to develop miR-125b as a biomarker for the diagnosis of GMB.

Temozolomide is an alkylating chemotherapeutic drug that readily crosses the blood–brain-barrier in GMB patients. It has been shown that TMZ possesses anti-tumour activity with relatively low toxicity in Phase I and Phase II clinical trials in patients with various advanced cancers, including malignant GMBs (Newlands et al, 1996). However, the action of TMZ in GMB cells remains largely undefined (Das et al, 2004). In the present study, we found that overexpression of miR-125b attenuated the sensitivity of GMB U87 cells to TMZ-induced apoptosis, while downregulation of miR-125b enhanced the sensitivity of TMZ. Our results are also consistent with a recent report of Shi et al (2012) in which they demonstrated that downregulation of miR-125b-2 expression could enhance TMZ-induced apoptosis though mitochondrial pathway in GMB stem cells (Shi et al, 2012). These results suggest that downregulation of miR-125b increases the sensitivity of TMZ in GMB, and it may provide a novel approach to GMB therapy.

The role of p53 in miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis is controversial. Some studies showed that p53 is a direct target of miR-125b, and overexpression of miR-125b inhibits p53-dependent apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells and Zebrafish embryos (Le et al, 2009b). However, there was other evidence to show that downregulated miR-125b increases cells apoptosis in ETV6/RUNX1 leukaemia REH cells without affecting the p53 expression level (Gefen et al, 2010). Our study confirmed that p53 is involved but is not necessary in miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis in U87 cells, because cell apoptosis was still observed in the cells with p53 silenced and knockdown of miR-125b. Our study provides a new insight into the understanding the function of miR-125 in glioma development and the possibility to develop miR-125b or its mimics as therapeutic agent for the treatment of glioma in patients with p53 mutation.

P38MAPK is involved in many cellular processes including development, differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis (Ghatan et al, 2000; Royuela et al, 2002; Wada and Penninger, 2004). In the present study, we found that miR-125b could negatively regulate p38MAPK expression; downregulate miR-125b and promote p38MAPK activation leading to GMB cell apoptosis. Similar results have been reported recently by Tan et al (2012); the results showed that miR-125b is upregulated during UV radiation and has an anti-apoptotic role by targeting p38α, one of isoform of p38 MAP kinase. Our study reveals that the miR-125b-mediated cell apoptosis is also in a p38MAPK-independent manner.

Take together, our studies reveal that miR-125b acts as an oncogene in GMB and has important roles in the growth and apoptosis of GMB cells. Both p53 and p38MAPK are involved in miR-125b-mediated apoptotic pathway. However, regulation of the growth and apoptosis by miR-125b in GMB cells is dependent on neither p53 nor p38MAPK. It is conceivable that there are multiple targets of miR-125b, and other genes may be involved in miR-125b-mediated cell death. Our results indicate that miR-125b regulates cell apoptosis in multiple signalling pathways and are consistent with previous reported studies. For example, the Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1 is targeted by miR-125b (Kong et al, 2011). MiR-125b also regulates apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by direct downregulation of Mcl-1, Bcl-w, Bcl-xL and interleukin (IL)-6R expression (Gong et al, 2013). It is possible that other target genes of miR-125b beyond p53 and p38MAPK signalling pathway such as NF-κB and TNF-α may also be regulated by miR-125b during cell apoptosis (Rajaram et al, 2011; Tan et al, 2012). Further study is still needed to address if miR-125b regulates the cell apoptosis by targeting other apoptotic pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Weicheng Yao and Jianpeng Wang for clinic tissues collection. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81072065; 81273550 and 41306157) and Basic Research Projects of Qingdao Science and Technology plan (12-1-4-8-(4)-jch).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Aqeilan RI, Zupo S, Dono M, Rassenti L, Alder H, Volinia S, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102 (39:13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Banik NL, Patel SJ, Ray SK. Dexamethasone protected human glioblastoma U87MG cells from temozolomide induced apoptosis by maintaining Bax:Bcl-2 ratio and preventing proteolytic activities. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:36. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gefen N, Binder V, Zaliova M, Linka Y, Morrow M, Novosel A, Edry L, Hertzberg L, Shomron N, Williams O, Trka J, Borkhardt A, Izraeli S. Hsa-mir-125b-2 is highly expressed in childhood ETV6/RUNX1 (TEL/AML1) leukemias and confers survival advantage to growth inhibitory signals independent of p53. Leukemia. 2010;24 (1:89–96. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatan S, Larner S, Kinoshita Y, Hetman M, Patel L, Xia Z, Youle RJ, Morrison RS. p38 MAP kinase mediates bax translocation in nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in neurons. J Cell Biol. 2000;150 (2:335–347. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout R, Miyakoshi J, Dobler KD, Andison R, Matsuo K, Allalunis-Turner MJ, Takebe H, Day RS., 3rd Lack of expression of tumor-suppressor genes in human malignant glioma cell lines. Oncogene. 1992;7 (9:1879–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Zhang JP, Li B, Zeng C, You K, Chen MX, Yuan Y, Zhuang SM. MicroRNA-125b promotes apoptosis by regulating the expression of Mcl-1, Bcl-w and IL-6R. Oncogene. 2013;32 (25:3071–3079. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Yao H, Zheng Z, Qiu G, Sun K. MiR-125b targets BCL3 and suppresses ovarian cancer proliferation. Int J Cancer. 2011;128 (10:2274–2283. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM. MicroRNAs as tumor suppressors. Nat Genet. 2007;39:582–583. doi: 10.1038/ng0507-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun S, Lee JH, Jin H, Nam J, Namkoong B, Lee G, Chung J, Kim VN. Conserved MicroRNA miR-8/miR-200 and its target USH/FOG2 control growth by regulating PI3K. Cell. 2009;139 (6:1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio MV, Visone R, Di Leva G, Donati V, Petrocca F, Casalini P, Taccioli C, Volinia S, Liu CG, Alder H, Calin GA, Ménard S, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67 (18:8699–8707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120 (5:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HH, Kuwano Y, Srikantan S, Lee EK, Martindale JL, Gorospe M. HuR recruits let-7/RISC to repress c-Myc expression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1743–1748. doi: 10.1101/gad.1812509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klusmann JH, Li Z, Böhmer K, Maroz A, Koch ML, Emmrich S, Godinho FJ, Orkin SH, Reinhardt D. miR-125b-2 is a potential oncomiR on human chromosome 21 in megakaryoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev. 2010;24:478–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.1856210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Sun C, Wang Z, Han L, Weng D, Lu Y, Chen Gl. miR-125b confers resistance of ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin by targeting pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2011;31 (4:543–549. doi: 10.1007/s11596-011-0487-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, Xie H, Zhou B, Chia PH, Rizk P, Um M, Udolph G, Yang H, Lim B, Lodish HF. MicroRNA-125b promotes neuronal differentiation in human cells by repressing multiple targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29 (19:5290–5305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01694-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, Teh C, Shyh-Chang N, Xie H, Zhou B, Korzh V, Lodish HF, Lim B. MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes Dev. 2009;23 (7:862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, Shyh-Chang N, Khaw SL, Chin L, Teh C, Tay J, O'Day E, Korzh V, Yang H, Lal A, Lieberman J, Lodish HF, Lim B. Conserved regulation of p53 network dosage by microRNA-125b occurs through evolving miRNA-target gene pairs. PLoS Genet. 2011;7 (9:e1002242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Kim HK, Chung S, Kim KS, Dutta A. Depletion of human micro-RNA miR-125b reveals that it is critical for the proliferation of differentiated cells but not for the downregulation of putative targets during differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280 (17:16635–16641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel S, Venturini L, Przybylski GK, Grabarczyk P, Schmidt CA, Meyer C, Drexler HG, Macleod RA, Scherr M. Activation of miR-17-92 by NK-like homeodomain proteins suppresses apoptosis via reduction of E2F1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50 (1:101–108. doi: 10.1080/10428190802626632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlands ES, O'Reilly SM, Glaser MG, Bower M, Evans H, Brock C, Brampton MH, Colquhoun I, Lewis P, Rice-Edwards JM, Illingworth RD, Richards PG. The charing Cross Hospital experience with temozolomide in patients with gliomas. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A (13:2236–2241. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoloso MS, Spizzo R, Shimizu M, Rossi S, Calin GA. MicroRNAs—the micro steering wheel of tumour metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9 (4:293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrc2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson P, Lu J, Zhang H, Shai A, Chun MG, Wang Y, Libutti SK, Nakakura EK, Golub TR, Hanahan D. MicroRNA dynamics in the stages of tumorigenesis correlate with hallmark capabilities of cancer. Genes Dev. 2009;23 (18:2152–2165. doi: 10.1101/gad.1820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram MV, Ni B, Morris JD, Brooks MN, Carlson TK, Bakthavachalu B, Schoenberg DR, Torrelles JB, Schlesinger LS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipomannan blocks TNF biosynthesis by regulating macrophage MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) and microRNA miR-125b. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 (42:17408–17413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112660108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royuela M, Arenas MI, Bethencourt FR, Sanchez-Chapado M, Fraile B, Paniagua R. Regulation of proliferation/apoptosis equilibrium by mitogen-activated protein kinases in normal, hyperplastic, and carcinomatous human prostate. Hum Pathol. 2002;33 (3:299–306. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.32227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempere LF, Freemantle S, Pitha-Rowe I, Moss E, Dmitrovsky E, Ambros V. Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 2004;5 (3:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Zhang J, Pan T, Zhou J, Gong W, Liu N, Fu Z, You Y. MiR-125b is critical for the suppression of human U251 glioma stem cell proliferation. Brain Res. 2010;1312:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Zhang S, Feng K, Wu F, Wan Y, Wang Z, Zhang J, Wang Y, Yan W, Fu Z, You Y. MicroRNA-125b-2 confers human glioblastoma stem cells resistance to temozolomide through the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2012;40 (1:119–129. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi XB, Xue L, Ma AH, Tepper CG, Kung HJ, White RW. miR-125b promotes growth of prostate cancer xenograft tumor through targeting pro-apoptotic genes. Prostate. 2011;71 (5:538–549. doi: 10.1002/pros.21270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G, Niu J, Shi Y, Ouyang H, Wu ZH. NF-kappaB-dependent MicroRNA-125b up-regulation promotes cell survival by targeting p38alpha upon ultraviolet radiation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287 (39:33036–33047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meir EG, Kikuchi T, Tada M, Li H, Diserens AC, Wojcik BE, Huang HJ, Friedmann T, de Tribolet N, Cavenee WK. Analysis of the p53 gene and its expression in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54 (3:649–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Penninger JM. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation. Oncogene. 2004;23:2838–2849. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Belasco JG. Micro-RNA regulation of the mammalian lin-28 gene during neuronal differentiation of embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25 (21:9198–9208. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9198-9208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Zhao X, Liu M, Liu H, Yao W, Zhang Y, Cao S, Lin X. Role of microRNA-26b in glioma development and its mediated regulation on EphA2. PLoS One. 2011;6 (1:e16264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia HF, He TZ, Liu CM, Cui Y, Song PP, Jin XH, Ma X. MiR-125b expression affects the proliferation and apoptosis of human glioma cells by targeting Bmf. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;23 (4-6:347–358. doi: 10.1159/000218181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Wu N, Ding L, Liu M, Liu H, Lin X. Zebrafish p53 protein enhances the translation of its own mRNA in response to UV irradiation and CPT treatment. FEBS Lett. 2012;586 (8:1220–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Ding Y, Liu H, Xi Y, Xiong W, Li G, Lu J, Fodstad O, Riker AI, Tan M. MicroRNA-125b confers the resistance of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel through suppression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1 (Bak1) expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285 (28:21496–21507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Chen J, Cong X, Hu S, Chen X. Hypoxia and serum deprivation-induced apoptosis in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24 (2:416–425. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.