Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the trends and trend changes in myocardial infraction (MI) and coronary heart disease (CHD) admissions, to investigate the effects of the 2007 smoke-free legislation on these trends, and to consider the policy implications of any findings.

Design setting

Liverpool (city), UK.

Participants

Hospital episode statistics data on all 56 995 admissions for CHD in Liverpool between 2004 and 2012 (International Classification of Diseases codes I20–I25 coded as an admission diagnosis within the defined dates).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Trend gradient and change points (by trend regressions analysis) in age-standardised MI admissions in Liverpool between 2004 and 2012; by sex and by socioeconomic status. Secondary analysis on CHD admissions.

Results

A significant and sustained reduction was seen in MI admissions in Liverpool beginning within 1 year of the smoking ban. Comparing 2005/2006 and 2010/2011, the age-adjusted rates for MI admissions fell by 42% (39–45%) (41.6% in men and by 42.6% in women). Trend analysis shows that this is significantly greater than the background trend of decreasing admissions. These reductions appeared consistent across all socioeconomic groups. Interestingly, admission rates for total CHD (including mild to severe angina) increased by 10% (8–12%).

Conclusions

A dramatic reduction in MI admissions in Liverpool has been observed coinciding with the smoking ban in 2007. Furthermore, the benefits were apparent across the socioeconomic spectrum. Health inequalities were not affected and may even have been reduced. The rapid effects observed with this top-down, environmental policy may further increase its value to policymakers.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An inclusive, accurate dataset was used (from mandatorily collected hospital episode statistics (HES) data for Liverpool), ensuring the identification of almost all relevant data cases, therefore minimising the selection bias.

A relatively long period of time before and after the smoking ban (2004–2012) compared with other studies, allowing a longer trend analysis.

Data quality issues meant that the older HES data before 2004 was not suitable to be included in this or other research studies on HES data of this type.

Small population groups after stratifying by socioeconomic status led to wide CIs. A follow-up study examining the Merseyside county as a whole aims to rectify this by including a larger population while still sharing similar health characteristics such as deprivation and smoking rates.

Introduction

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the UK,1 particularly for cardiovascular disease2; the UK prevalence of smoking was around 22% in 2007, representing some 13.7 million smokers.3 Furthermore, strong socioeconomic inequalities were apparent, with the smoking rates being around 14% in the most affluent groups and 34% in the most deprived.4

The WHO suggested the smoke-free legislation as one of the key strategies to reduce the adverse impact the tobacco has on health.5 The smoke-free legislation in England was enacted on 1 July 2007 which made it illegal to smoke in any enclosed public or work space.

A body of evidence now exists demonstrating that the smoke-free legislation is highly effective in reducing the second-hand smoke exposure.6

It is important to generate evidence for public health interventions where possible, especially as in many cases other traditional ways of gathering evidence such as randomised controlled trials are often not feasible.7 Lawrence et al7 in 2011 described a ‘global research neglect’ of population health interventions in the field of tobacco control, and a tendency for smoking cessation research to favour individual-based over population-based approaches.

Liverpool (pop: ∼450 000) ranks among the worst-performing cities in the UK in terms of heart disease, socioeconomic status, smoking prevalence8 9 and healthcare costs associated with smoking.8 Population-level interventions, such as smoking bans in public places, may potentially reduce the health inequalities. There is thus a great potential for a study to evaluate the smoking ban in this city, both in terms of health outcomes and, crucially, in differential effects by socioeconomic status.

Methods

Mortality and morbidity statistics

All admissions for patients aged 16 and over in Liverpool from January 2004 to April 2012 with an International Classification of Diseases diagnosis code from I20 to I25 for coronary heart disease (CHD) were extracted from the hospital episode statistics (HES)i database by Liverpool Primary Care Trust (PCT)ii Health Intelligence staff. This data were presented anonymised and secured on official health-service hardware and networks only.

Although we do not think that the out-of-area healthcare use of this diagnosis was significant, we were not able to analyse this in detail.

Unfortunately the HES data that was available at the time did not allow us to link the smoking status with the admissions, so we were not able to consider this in the analysis.

Age adjustment was performed using the direct method to the European standard population.

Socioeconomic status data

The 30 wards of Liverpool were manually categorised into 3 groups of 10 wards each—that is, the 10 most deprived, the 10 least deprived and the 10 in the middle. To retain a greater statistical power, smaller divisions such as individual wards were not used. Individual socioeconomic status for the wards was estimated by the geographical area using average socioeconomic rankings for the Lower Super Output Areas of Liverpool, as calculated by the Liverpool City Council.10

We then obtained data on CHD admissions by age, sex and socioeconomic status for the period 2004–2012.

Trend analysis

A preliminary analysis of the time plots of the age-adjusted mortality rates was carried out to detect the patterns such as trend or seasonality.

Plots of the age-specific mortality rates were smoothed using 3-period moving averages, to help reduce the exaggerated effect that outlying points can have on mean trend analysis models when these points are very close to either end of the study period. A Joinpoint regression was fitted to provide the estimated annual percentage change and to detect the points in time where significant changes in the trends occur (JOINPOINT software V.3.0).11 We used a Bayesian Information Criterion approach to select the most parsimonious model that fits best the data. A maximum number of five Joinpoints were allowed for estimations. For each annual percentage change estimate, we also calculated the corresponding 95% CI. We performed several Joinpoint regression analyses: one for sex-specific age-adjusted CHD admission rates, one for sex-specific age-adjusted MI admission rates and one for deprivation-specific age-adjusted MI admission rates.

Rate ratios were also calculated for average rates for the first 2 calendar-years of the study (before the smoking ban 2005–2006) with the last 2 years of the study (after the smoking ban 2010–2011). Although background, secular trends were not factored into the calculations at this time, it allows the results to be seen in context of other studies which have presented results as ‘percentage decreases’.12 However, we emphasise the importance of the complete trend analysis figures to provide a full context for the data.

As an alternative methodology, we fitted ARIMA models13 to sex-specific and deprivation-specific MI admission rates. ARIMA preliminary analysis, model selection and model fitting were undertaken using the Time Series Modeller procedure of SPSS V.20. Smoking ban policy was included in the models as an event variable where a value of 1 indicates times at which the dependent series were expected to be affected by the smoking policy ban. Finally, we used the Ljung-Box tests to assess the suitability of the models.

Results

Sex-specific age-adjusted CHD admission trends

Comparing ‘05–‘06 and ‘10–‘11, the age-adjusted CHD admission rates increased overall by 8% in men and by 12% in women (table 1). The Joinpoint analysis identified several changes in the trend during the study period, although none were within two-quarters of the smoking ban (ie, appearing to correspond with the time around the smoking ban).

Table 1.

Descriptive data for all coronary heart disease admissions in Liverpool between January 2004 and March 2012, including comparisons between 2005/2006 and 2010/2011

| Population characteristics 2004–2012 |

Crude admissions |

Age-adjusted rates per 100 000* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Per cent | 2005–2006 | 2010–2011 | Difference | 2005–2006 | 2010–2011 | Rate ratio | |

| Total | 56 995 | 100 | 13 434 | 15 523 | +2089 | 1696.7 | 2097.1 | 1.10 (1.08–1.12) |

| Male | 30 236 | 53.1 | 7167 | 8271 | +1104 | 2064.0 | 2235.4 | 1.08 (1.06–1.11) |

| Female | 26 759 | 46.9 | 6267 | 7252 | +985 | 1371.5 | 1542.2 | 1.12 (1.09–1.16) |

| 16–19 | 11 | <0.1 | 2 | 3 | +1 | 3.4 | 5.8 | 1.70 |

| 20–29 | 55 | 0.1 | 15 | 12 | −3 | 9.1 | 6.4 | 0.699 |

| 30–39 | 448 | 0.8 | 127 | 87 | −40 | 109.1 | 81.0 | 0.742 |

| 40–49 | 3526 | 6.2 | 933 | 830 | −103 | 763.5 | 707.0 | 0.926 |

| 50–59 | 9211 | 16.2 | 2366 | 2339 | −27 | 2351.9 | 2236.1 | 0.951 |

| 60–69 | 13 647 | 23.9 | 3290 | 3650 | +360 | 4386.7 | 4632.0 | 1.06 |

| 70–79 | 17 578 | 30.8 | 4053 | 4883 | +830 | 6622.6 | 8220.5 | 1.24 |

| 80+ | 12 519 | 22.0 | 2648 | 3719 | +1071 | 8406.4 | 11 068.5 | 1.32 |

*Final age-adjusted rates and CIs calculated for total, male and female rates only. Age-specific rates and rate ratios are raw rates shown for reference.

Sex-specific age-adjusted MI admission trends

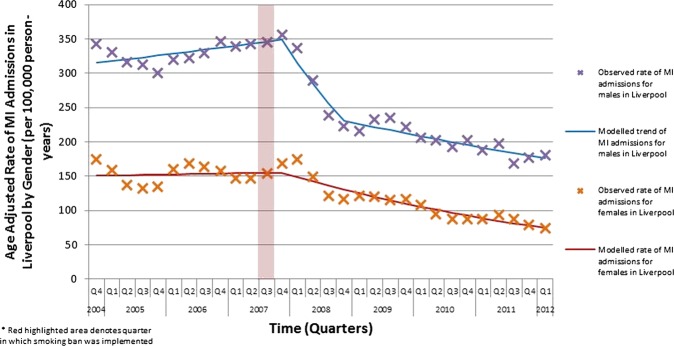

Comparing ‘05–‘06 and ‘10–‘11, the age-adjusted rates specifically for MI admissions decreased overall by 41.6% in men and by 42.6% in women (table 2). The Joinpoint analysis identified a change in trend corresponding to Q4 2007. In men, this represented a change from Annual Percentage Change (APC) of 0.9% (0.1 to 1.6) to APC −9.8% (−15.5 to −3.7). For women, this was a change from APC 0.2% (−1.2 to 1.7) to APC −4.2% (−5.0 to −3.4) (figure 1).

Table 2.

Descriptive data for myocardial infarction admissions in Liverpool between January 2004 and March 2012, including comparisons between 2005/2006 and 2010/2011

| Population characteristics 2004–2012 |

Crude admissions |

Age-adjusted rates/100 000* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Per cent | 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 2005–2006 | 2010–2011 | Rate ratio | |

| Total | 6356 | 100 | 1881 | 1089 | −792 | 230.3 | 134.2 | 0.583 (0.549–0.618) |

| Male | 3799 | 59.8 | 1135 | 682 | −453 | 325.3 | 190.0 | 0.584 (0.542–0.629) |

| Female | 2557 | 40.2 | 746 | 407 | −339 | 148.7 | 85.3 | 0.574 (0.520–0.633) |

| 16–19 | 2 | <0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

| 20–29 | 11 | 0.2 | 4 | 1 | −3 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.219 |

| 30–39 | 91 | 1.4 | 20 | 16 | −4 | 17.2 | 14.9 | 0.867 |

| 40–49 | 488 | 7.7 | 149 | 81 | −68 | 121.9 | 69.0 | 0.566 |

| 50–59 | 1016 | 16.0 | 286 | 221 | −65 | 284.3 | 211.3 | 0.743 |

| 60–69 | 1376 | 21.6 | 405 | 226 | −179 | 540.0 | 286.8 | 0.531 |

| 70–79 | 1763 | 27.7 | 531 | 291 | −240 | 867.6 | 489.9 | 0.565 |

| 80+ | 1609 | 25.3 | 486 | 253 | −233 | 1542.9 | 753.0 | 0.488 |

*Final age-adjusted rates and CIs calculated for total, male and female rates only. Age-specific rates and rate ratios are raw rates shown for reference.

Figure 1.

Observed and modelled rates for all myocardial infarction admissions in Liverpool, 2004–2012, divided by gender.

The rate ratio comparing the first 2 years of the study (just before the smoking ban) and the final 2 years of the study was 0.58 (0.54 to 0.61).

Socioeconomic differentials in MI admission trends

Gender-specific figures were not analysed, as the denominators became too low to be robust.

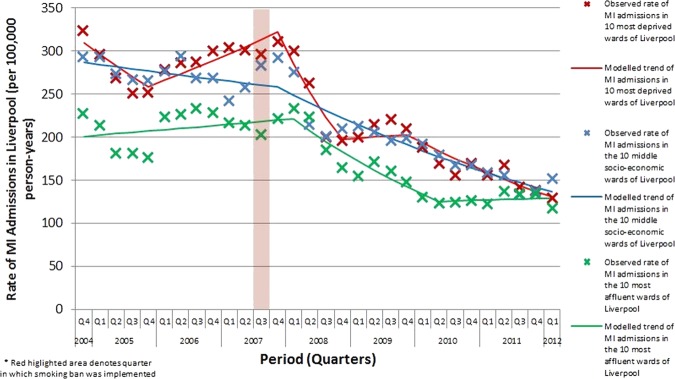

For the 10 most deprived wards, MI admissions reduced by 45% (58.0 to 28.4) between '05–'06 and '10–'11. The Joinpoint analysis identified a trend change at 2007 Q4, representing a trend change from APC 2.8% (1.0 to 4.6) to APC −11.5% (−17.0 to −5.6) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Observed and modelled rates for all myocardial infarction admissions in Liverpool, 2004–2012, subdivided into three socioeconomic groupings (the 10 most deprived wards, the 10 middle-ranked wards and the 10 most affluent wards).

For the 10 middle-ranked wards, MI admissions reduced by 42.3% (56.4 to 23.6) between ‘2005-2006’ and ‘2010-2011’. The Joinpoint analysis identified a trend change at 2007 Q4, representing a trend change from APC 0.9% (−1.9 to 0.2) to APC −3.7% (−4.3 to −3.1) (figure 2).

For the 10 most affluent wards, MI admissions reduced by 38.6% (57.5 to 11.2) between ‘2005-2006’ and ‘10-11’. The Joinpoint analysis identified a trend change at 2008 Q1, representing a trend change from APC 0.7% (−0.6 to 2.1) to APC −6.1% (−8.7 to −3.5) (figure 2).

The average absolute risk difference between the most and the least deprived wards over the first 2 years of the dataset was 69.8 MI admissions per 100 000 person-years. In contrast, the rate for the final 2 years was 32 MI admissions per 100 000 person-years (A rate ratio of 0.46, 95% CI of 0.044 to 4.76).

The average rate ratio between the most and the least deprived wards over the first 2 years of the dataset was 1.38. In contrast, the relative difference for the final 2 years was 1.26 (A ratio of 0.91, 95% CI of 0.43 to 1.91).

ARIMA analysis

There is a statistically significant decreasing effect of smoking ban policy for men, delayed by 3 points on time (eg, three quarters) found in the MI admissions for males, the most deprived wards and the middle-ranked wards (table 3). Surprisingly, the middle-ranked wards seem to be more affected by the smoking ban than the most deprived wards.

Table 3.

ARIMA model parameters

| Model | Parameter | Estimate | SE | t | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males* | Independent variable (three period delay) | Lag 0 | −11.81 | 3.23 | −3.65 | 0.00 |

| Lag 1 | 12.85 | 3.23 | 3.97 | 0.00 | ||

| Females*† | AR | Lag 1 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 4.72 | 0.00 |

| Lag 2 | −0.57 | 0.16 | −3.62 | 0.00 | ||

| Most-deprived wards*‡ | Independent variable (three period delay) | Lag 0 | −43.65 | 18.32 | −2.38 | 0.03 |

| Middle-ranked wards* | Independent variable (three period delay) | Lag 0 | −60.28 | 13.70 | −4.40 | 0.00 |

| Most-affluent wards*§ | Constant | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.37 | 0.18 |

*Difference order 1.

†Square transformation.

‡Seasonal difference order 1.

§Natural log transformation.

The Ljung-Box tests (table 4) indicate a reasonable good fit of the models (with the exemption of the model for the most affluent wards).

Table 4.

Models goodness of fit: Ljung-Box test

| Model | Ljung-Box Q(18) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | DF | Significance | |

| Males | 18.77 | 18.00 | 0.41 |

| Females | 12.35 | 16.00 | 0.72 |

| Most-deprived wards | 24.86 | 18.00 | 0.13 |

| Middle-ranked wards | 19.42 | 18.00 | 0.37 |

| Most-affluent wards | 31.87 | 18.00 | 0.02 |

More details of the ARIMA methodology can be found in tables 3 and 4.

Discussion

Main findings

MI admissions in Liverpool showed a dramatic and statistically significant decline coinciding with the introduction of the smoking ban in July 2007. This decline was substantially greater than the underlying secular trend. In spite of a slight deceleration of the rate of decline in 2009, the decreasing rates have clearly continued until the end of 2012. This very substantial decrease in the rate was statistically significant. Even when bearing in mind some background secular trends, the reduction in the number of admissions by over 40% is still striking.

In contrast, the total CHD admissions apparently increased by approximately 10% during the same period. There are several possible reasons for this discrepancy, including the greater difficulty in diagnosis or exclusion of angina chest pain, resulting in a higher number of false positives, false negatives or miscoding (eg, mild or atypical chest pain). MIs, however, are more clearly diagnosed, and include clearly defined clinical and diagnostic criteria (eg, biochemical markers and specific ECG changes).

The rapid effect of the smoke-free legislation on MI admissions was notable. As in similar studies elsewhere the introduction of the smoke-free legislation rapidly resulted in reduced admissions for acute MIs.14 Despite a slight reduction in the rate of decline in 2009, our data still suggest that the smoking ban has a sustained and long-term effect, which is consistent with the previous systematic reviews.15

Sims et al12 in 2010 found that the smoke-free legislation in England reduced the emergency admissions from MI by 2.4% over a 15-month follow-up period. Further research will be necessary to ascertain whether the greater effect seen in the findings of our study compared with other national studies is because of the unique characteristics of the Liverpool demographic (higher baseline rates of heart disease/smoking; higher rates of deprivation) or some other environmental or statistical phenomenon. Interestingly, one study16 found a declining trend in MI in England beginning well before 2007 (their study going back to 2002) and appears to show a steady linear decrease in MI admissions from 2002 to 2010, with no changes in the speed of decline around the time of the implementation of the smoking ban. Their study aggregated the data for England using HSE ‘incident’ cases of MI (ie, new cases)—all MI events within a 30-day window are only considered once; whereas in our study all events are considered including multiple heart attacks in single individuals. A possible explanation could be that the smoking ban has a greater specific effect in reducing the repeat or relapse MIs but not greatly reducing the number of ‘first’ MIs.

A relatively few studies have examined the effect of socioeconomic status on health gains following smoking bans17; however, our findings do agree with the conclusions of Dinno and Glantz's study in 2009 which explored this. To examine the effects of the smoke-free legislation smoking behaviour, they compared effects across the racial/ethnic backgrounds and household income, and found that the smoke-free legislation does appear to benefit all socioeconomic and race/ethnic groups equally.18 Our crude figures suggest a possible reduction in both absolute inequalities (differences) and relative inequalities (ratios), albeit not yet at a statistically significant level. The trend across the socioeconomic groups appears to suggest a possible greater favourable effect in more deprived demographics, and this might also explain the greater effect of the smoking ban in Liverpool compared with other populations.

In addition, the ARIMA results are broadly consistent with the Joinpoint analysis: both lend support that the smoking ban policy as population level intervention does not increase the inequalities. Moreover, as the results of the ARIMA analysis pointed out, it has the potential to reduce the inequalities.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was an inclusive, accurate dataset through strict and specific data collection criteria over a period of 8 years. In addition, using mandatorily collected HES data, all relevant data cases are likely to have been identified, minimising a potential source of selection bias.

As with any other study, our analysis has several limitations. First, data quality issues prevented the use of the older HES data before 2004. This meant that the extremely long secular or cyclical trends may have been missed. What it can say is that there is a dramatic and statistically significant drop in the trends of MI rates in Liverpool corresponding with the time of the smoking ban, and that reduced rates have subsequently been maintained. The use of methodological techniques such as controls was also not feasible—the smoking ban was implemented in all the English regions simultaneously.

The small number of Liverpool cases analysed resulted in wide CIs. We would emphasise that any inferences should be cautious, and should emphasise the urgent need for future research, particularly the subanalysis (eg, by socioeconomic characteristics). Replicating these analyses in larger populations (Merseyside, which as a region, shares similar health characteristics such as deprivation and smoking rates) may therefore be valuable.

Also the ARIMA results should be taken cautiously since there is some evidence that suggests that the ARIMA models do not perform well in small samples.19 Because of the sample size, the study may be underpowered to adequately estimate the real effect of the smoking ban. From this perspective, the Joinpoint regression seems to be a more adequate and robust methodology to explore the effect of smoking policy ban.

Public health implications

The implementation of the smoking ban was part of a national strategy to improve the health of the population, especially through reducing the second-hand smoke exposure. The results from studies such as this may directly influence the decisions regarding implementation of future, similar health legislation aimed at the population level.

From a policy perspective, these findings suggest that the health policies need to continue to change from a focus towards incentives for short-term clinical and individual interventions such as through Quality and Outcomes Framework or pay-by-results schemes20 to a focus on the primary prevention strategies that reduce the disease by tackling the risk factors21 at a population level, as well as driving changes in societal perceptions and health behaviours. This is especially topical given the debate around various population-level proposals with public health implications such as alcohol unit pricing.

Furthermore, this study highlights the potential speed of return of health benefits gained from such wide-net population-level interventions. It adds to a growing body of evidence that substantial declines in mortality can happen rapidly after population-wide changes in risk factors such as diet or smoke-exposure.22 23 Policy interventions which achieve population-wide changes related to CHD and smoking can be powerfully effective and cost-saving.24

Such structural, upstream interventions – if adequately designed and enforced – could not only result in large and rapid gains,15 but could also reduce inequalities,25 or at least not generate or aggravate them. However, the evidence base is still sparse, and more empirical evidence to support this hypothesis is needed.26 The evaluation of these individual policy interventions is important to determine their effectiveness to document the case for extending programmes to other jurisdictions, to aid in refining programme implementation and to monitor the possibility of inadvertent consequences. Although such policies and their evaluations are often politically challenging, they are emerging as powerful options to reduce the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases.

In conclusion, a dramatic reduction in MI admissions in Liverpool has been observed coinciding with the smoking ban in 2007. This is consistent with results in other settings and populations. Furthermore, early data suggest that the effect is consistent across the socioeconomic spectrum. This legislation does not appear to affect the health inequalities and may even reduce them. The rapid effects observed with this top-down, population-wide policy further emphasise its potential value to Public Health policymakers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

HES is a secure records-based data system containing details of all admissions, outpatient appointments and A&E attendances at National Health Service hospitals in England, collected during a patient's time in hospital. More information is available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes

At the time of the study period primary care trusts (PCTs) were the main organisational and commissioning units in the English National Health System, including commissioning primary care and the majority of secondary care services.

Contributors: AL contributed significantly for the paper overall. MGC provided substantial contribution via ARIMA modelling and writing of relevant paragraphs. SC was involved in the interpretation of data, review and revision of the manuscript and key points especially regarding smoking behaviour, cardiovascular disease science, CVD epidemiology and implications on health equity. JL was involved in conception, interpretation of data, review and revision of the manuscript key points especially regarding local authority and public health policy and strategy. MO was involved in conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critically reviewing and revising the drafts and key points. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: London-Dulwich Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.The Lancet GBD UK estimates Lancet Feb 2013. 2013. http://www.thelancet.com/themed/tobacco-control

- 2.Bajekal M, Scholes S, Love H, et al. Analysing recent socioeconomic trends in coronary heart disease mortality in England, 2000-2007: a population modelling study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Information Center for Heath and Social Care Health Survey for England 2007: Latest Trends. 2008

- 4.Simpson CR, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology of smoking recorded in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e121–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DoH Smokefree England—one year on. NHS, 2008. http://www.smokefreeengland.co.uk/files/dhs01_01-one-year-on-report-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callinan J, Clarke A, Doherty K, et al. Legislative smoking bans for reducing secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2010;14:CD005922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Global research neglect of population-based approaches to smoking cessation: time for a more rigorous science of population health interventions. Addiction 2011;106:1549–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.APHO Association of Public Health Observatories. Report: Health Profile—Liverpool, 2010. http://www.apho.org.uk/resource/item.aspx?RID=50308

- 9.LHO Smoking Prevalence among Adults aged 18+ by region and local authority. 2012

- 10.Liverpool City Council Key Statistics, Data, Deprivation Data. Published Online First: 2011. http://liverpool.gov.uk/council/key-statistics-and-data/data/deprivation/

- 11.National Cancer Institute Joinpoint regression programme. Surveillance Research, Cancer Control and Population Sciences; 2012. http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sims M, Maxwell R, Bauld L, et al. Short term impact of smoke-free legislation in England: retrospective analysis of hospital admissions for myocardial infarction. BMJ 2010;340:c2161.http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2882555&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract (accessed 12 Nov 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Box G, GM J. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. D J Bartholomew Operational Res Q 1971;22:199–201 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasselli S, Papini P, Gaelone D, et al. Reduction incidence of myocardial infarction associated with a national legislative ban on smoking. Minerva Cardioangiol 2008;56:197–203 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18319698 (accessed 11 May 2012) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan CE, Glantz SA. Association between smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory diseases: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2012;126:2177–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, et al. Determinants of the decline in mortality from acute myocardial infarction in England between 2002 and 2010: linked national database study. BMJ 2012;344:d8059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackay DF, Irfan MO, Haw S, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of comprehensive smoke-free legislation on acute coronary events. Heart 2010;96:1525–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinno A, Glantz S. Tobacco control policies are egalitarian: a vulnerabilities perspective on clean indoor air laws, cigarette prices, and tobacco use disparities. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1439–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abeysinghe T, Balasooriya U, Tsui A. Small-sample forecasting regression or ARIMA models? J Quant 2003:1–22 http://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/ecstabey/tilak bala albert-2.pdf (accessed 6 Sep 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 20.DoH Using the commissioning for quality and innovation (CQUIN) payment framework. London: DoH, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden A, et al. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:284–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capewell S, O'Flaherty M. Can dietary changes rapidly decrease cardiovascular mortality rates? Eur Heart J 2011;32:1187–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capewell S, O'Flaherty M. Rapid mortality falls after risk-factor changes in populations. Lancet 2011;378:752–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NICE Prevention of cardiovascular disease at population level. 2010. http://www.nice. org.uk/nicemedia/live/13024/49273/49273.pdf

- 25.Capewell S, Graham H. Will cardiovascular disease prevention widen health inequalities? PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, et al. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:190–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.