Abstract

Objective

To assess the effects of famine exposure during childhood on coronary calcium deposition and, secondarily, on cardiac valve and aortic calcifications.

Design

Retrospective cohort.

Setting

Community.

Patients

286 postmenopausal women with individual measurements of famine exposure during childhood in the Netherlands during World War II.

Intervention/exposure

Famine exposure during childhood.

Main outcome measures

Coronary artery calcifications measured by CT scan and scored using the Agatston method; calcifications of the aorta and cardiac valves (mitral and/or aortic) measured semiquantitatively. Logistic regression was used for coronary Agatston score of >100 or ≤100, valve or aortic calcifications as the dependent variable and an indicator for famine exposure as the independent variable. These models were also used for confounder adjustment and stratification based on age groups of 0–9 and 10–17 years.

Results

In the overall analysis, no statistically significant association was found between severe famine exposure in childhood and a high coronary calcium score (OR 1.80, 95% CI 0.87 to 3.78). However, when looking at specific risk periods, severe famine exposure during adolescence was related to a higher risk for a high coronary calcium score than non-exposure to famine, both in crude (OR 3.47, 95% CI 1.00 to 12.07) and adjusted analyses (OR 4.62, 95% CI 1.16 to 18.43). No statistically significant association was found between childhood famine exposure and valve or aortic calcification (OR 1.66, 95% CI 0.69 to 4.10).

Conclusions

Famine exposure in childhood, especially during adolescence, seems to be associated with a higher risk of coronary artery calcification in late adulthood. However, the association between childhood famine exposure and cardiac valve/aortic calcification is less clear.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, NUTRITION & DIETETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study has limited statistical power.

This study is unique for the combined availability of individual famine exposure data and thoracic CT images.

This study provides an insight into the mechanism of the reported association between famine in adolescence and cardiovascular events.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Globally, ischaemic heart and cerebrovascular diseases are major causes of death and it has been projected that this condition will not change in the next 20 years, resulting in 20 million deaths per year in 2030.1 Despite advances in treatment, such diseases still have a significant impact on quality of life2 and cause great economic burden. As such, effective prevention is essential.

Evidence suggests that many chronic diseases originate from particular events in early life. Since Barker first proposed the developmental origins of health and diseases hypothesis,3 4 many studies have indicated that adverse influences, such as undernutrition during growth and development, might result in permanent physiological and metabolic alterations.5–7 Such alterations may benefit short-term survival, but at the expense of increased risk of chronic diseases later in life.8 However, the exact critical periods have yet to be defined9 as to whether they extend beyond fetal life and infancy into childhood and adolescence.

Although studies on the fetal and infant periods are numerous, there is little data on the effect of childhood and adolescent nutritional disturbances on cardiovascular risk. Moreover, most studies evaluated postnatal disturbances as a consequence of prenatal events. As suggested by several large cohort studies,10–13 growth patterns after birth seem to be associated with a substantial increase in risk for cardiovascular and metabolic disorders.

Undernutrition during childhood and adolescence may have chronic disease consequences. Studies on the Dutch 1944–1945 famine in World War II showed that severe famine exposure in adolescence was associated with a 30% increased risk of coronary heart diseases14 and a fourfold to fivefold increased risk of diabetes mellitus and/or peripheral arterial disease in older women.15 Men who experienced severe starvation around the time of puberty were reported to have a 40–60% increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke.16 However, despite circumstantial evidence showing that childhood famine may lead to a similar ‘catch up fat phenotype’ as underweight newborns,17 the mechanism by which food deprivation in these periods increases cardiovascular disease risk remains obscure. Since coronary artery calcium deposition has emerged as a strong predictor for cardiovascular diseases18 19 and likely represents pathological alterations of the vessel wall underlying clinically manifested disease,14 we investigated an association between childhood exposure to famine and coronary calcium deposition. As findings implicating the association between cardiac valve or aortic calcification and coronary cardiovascular events are also emerging,20–22 we also assessed for an association between childhood undernutrition and extracoronary (valve and aortic) calcification.

Subjects and methods

Study population

Our study was a subset of a larger Dutch cohort, Prospect-European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), part of the EPIC, as described elsewhere.23 Prospect-EPIC enrolled 17 357 healthy 49-year-old to 70-year-old women who underwent breast cancer screening and lived in Utrecht or the surrounding area between 1993 and 1997.

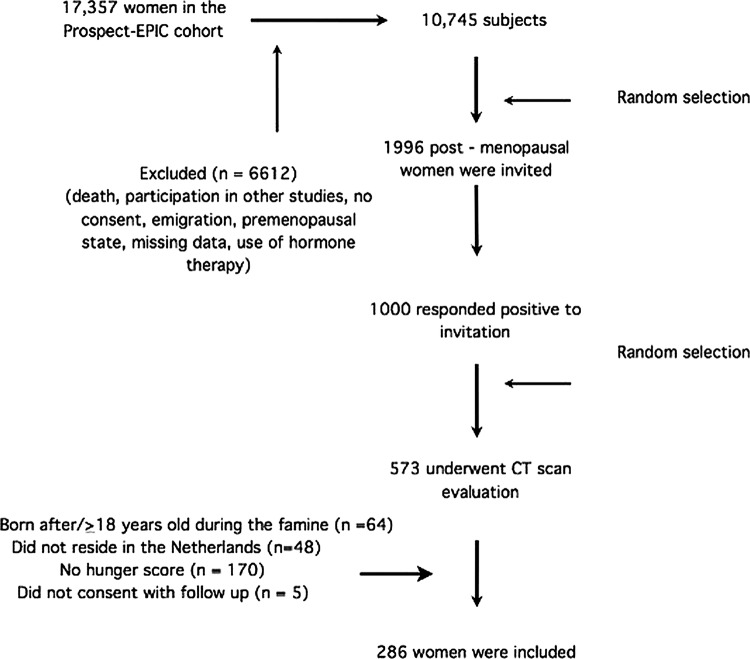

Our subset comprised 573 postmenopausal women, who had been evaluated for associations between metabolic and reproductive factors and coronary artery calcium.24 For our study, premenopausal women were excluded (n=1309). After further selection (figure 1), we obtained coronary CT scans of 573 women. We further excluded women who were born after or aged 18 years or over during the famine (n=64), resided outside occupied the Netherlands during the famine (n=48), had unavailable hunger scores (n=170) or did not consent to follow-up (n=5), leaving 286 women for our analyses. Data were collected from October 2002 until December 2004.

Figure 1.

Participants recruitment flow.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all women before their inclusion to the study.

Famine exposure

We employed a general questionnaire to evaluate the participants’ degree of exposure to famine. As detailed elsewhere,25 the Dutch famine occurred in the winters of 1944–1945 during World War II when banned food transport dramatically reduced food supplies in the western Netherlands, with official daily rations dropping to 400–800 kcal. After 6 months of starvation conditions, the Netherlands was liberated, abruptly ending the famine.

The questionnaire was used to collect information on place of residence as well as experiences of hunger and weight loss during the Dutch famine. The latter two questions had answer categories of ‘hardly,’ ‘little’ or ‘very much.’ Women who answered ‘not applicable’ or ‘I don't know’ to either of the two questions were excluded. Famine exposure was then categorised into a three-point score as follows: ‘severely exposed’ for women who reported having been ‘very much’ exposed to hunger and weight loss, ‘unexposed’ for those who were ‘hardly’ exposed to either hunger or weight loss, or ‘moderately exposed’ for all other responses.

Outcome assessment

CT imaging

Unenhanced CT imaging of the heart was performed using a 16-slice CT scanner (Mx8000 IDT 16; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands). During a single breath hold, a prospectively ECG-triggered (‘step-and-shoot’) CT scan was performed. The scan ranged from the tracheal bifurcation to below the apex of the heart. Scan parameters were 16×1.5 mm collimation, 205 mm field of view, 0.42 s rotation time, 0.28 s scan time per table position, 120 kVp and 40–70 mAs (patient weight 70 kg: 40 mAs; 70–90 kg: 55 mAs; 90 kg: 70 mAs). Scan duration was approximately 10 s, depending on heart rate and patient size.

Measurement of calcifications

After CT scan acquisition, coronary artery calcification (CAC) was quantified using Agatston's method26 on the 1.5 mm slices using software for calcium scoring (Heartbest-CS, EBW; Philips Medical Systems) by a trained scan reader (AR). The continuous score was dichotomised at a cut-off of 100 due to its highly skewed distribution. This cut-off value has been used clinically and scientifically to indicate cardiovascular risk. As published elsewhere,27 a cut-off above 100 is often referred to as moderate calcification, while a cut-off of 300 reflects heavy calcification. We also performed sensitivity analyses using different cut-off values (0 and 300).

We attempted to ensure reproducibility by having 199 scans read by two independent observers and by having 58 women undergo a second scan within 3 months. The inter-reader and interscan agreement were excellent with within-class correlation coefficients greater than 0.95.28

Valve and aortic calcification were quantified using the same CT dataset as the CAC evaluation. We divided calcification of the heart valves anatomically into aortic valve leaflet (AVL) and mitral valve leaflet (MVL) findings. The AVL and MVL calcifications were graded as 0 (absent), 1 (mild, meaning only one leaflet affected), or 2 (severe, 2 or 3 leaflets affected), as previously described.20 Owing to small number of participants, the grades were further dichotomised into absent or present for mild to severe calcification. We also computed assessed composite valve calcification, which was classified as ‘present‘ if calcification was detected in either of the two valves or ‘absent’ if no calcification was found in either the mitral or aortic valve.

For the thoracic aorta, we initially categorised the calcification into absent (none detected), mild (≤4 calcified foci or 1 calcification extending over ≥3 slices), moderate (>4 calcified foci or 2 calcifications extending over ≥3 slices) or severe (calcified aorta covering multiple segments). We later simplified this classification into none-to-mild (‘low’) and moderate-to-severe (‘high’) calcifications because of the small number of participants, especially those without calcification. A single reader (PAdJ) performed all CT evaluations while blinded for famine exposure status.

Measurement of potential confounders

We collected data on date of birth, cardiovascular disease history and established risk factors for cardiovascular diseases using questionnaires. Smoking was defined as current, past or never.

From fasting venous blood specimens, we measured plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose using standard enzymatic procedures, as well as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol by direct method (inhibition, enzymatic). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured by an automatic device (DINAMAP XL, Critikon; Johnson & Johnson, Tampa, Florida, USA). We took the higher value of either the right or the left arm measurement. Height and weight were also measured, and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Body fat distribution was assessed by measuring the waist-to-hip ratio. We defined diabetes mellitus as previously described.29

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics were tabulated into famine exposure categories for descriptive purposes and confounding assessment, and differences were tested using analysis of varience, χ2 or Kruskal-Wallis tests.

We used (adjusted) logistic regression with coronary calcium (Agatston >100 yes/no) as the dependent variable, and an indicator for famine exposure levels as the independent variable. Because age at famine exposure could be an effect modifier,14 we stratified the analysis by age groups, 0–9 years (preadolescence) and 10–18 years (adolescence). Since smoking may be a potential effect-modifier as it may increase sensitivity for environmental stressors, we stratified the analysis by smoking status. Adjustments were made for lipid profile, glucose level and waist-to-hip ratio for their known strong associations with cardiovascular diseases and possibly with malnutrition. Similar modelling was used to evaluate calcium deposition in the aorta and mitral/aortic valves. Results are expressed as ORs and 95% CIs. All analyses were conducted using SPSS V.19.0 for Mac.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study participants. Although not statistically significant, participants exposed to famine were slightly older, and had higher BMI, waist-to-hip ratio as well as triglyceride levels than the unexposed participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants based on famine exposure level

| Variables | Famine exposure |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexposed | Moderate | Severe | p Value | |

| n=139 | n=103 | n=44 | ||

| Age at famine, mean (SD) | 7.6 (4.7) | 8.9 (5.6) | 8.7 (4.3) | 0.10 |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| Through 9 years | 98 (70.5) | 64 (62.1) | 29 (65.9) | 0.39 |

| 10–18 years | 41 (29.5) | 39 (37.9) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Age at CT scan | 67.7 (5.0) | 69.0 (5.4) | 69.0 (4.7) | 0.11 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.4 (4.4) | 27.3 (4.6) | 27.8 (4.6) | 0.12 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.84 (0.07) | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.85 (0.06) | 0.06 |

| Highest systolic BP (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 141.5 (20.4) | 143.1 (23.4) | 145.0 (21.8) | 0.63 |

| Highest diastolic BP (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 75.4 (9.6) | 74.8 (9.6) | 74.6 (8.2) | 0.87 |

| Cholesterol to HDL ratio, mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.2) | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.2) | 0.43 |

| Glucose level (mmol/L), mean (SD) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.8 (1.2) | 5.5 (0.5) | 0.35 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L), median (range) | 1.0 (0.5–3.8) | 1.1 (0.3–3.7) | 1.3 (0.5–3.2) | 0.15* |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Currently | 9 (6.5) | 11 (10.7) | 3 (6.8) | 0.71 |

| Former | 57 (41.0) | 45 (43.7) | 18 (40.9) | |

| Never | 75 (52.5) | 47 (45.6) | 23 (52.3) | |

| Pack-years smoked in ever/current smokers, median (range) | 6.0 (0.05–94) | 7.4 (0.05–73.5) | 11.5 (0.03–53.8) | 0.66 |

| Pack-years smoked, median (range) | 0.0 (0.0–94) | 0.3 (0.0–73.5) | 0.0 (0.0–53.8) | 0.57* |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 15 (10.8) | 18 (17.5) | 3 (6.5) | 0.14 |

*Kruskal-Wallis test.

The association between famine exposure and coronary calcium score is shown in table 2. The overall analysis, crude and adjusted, showed that severe famine almost doubled the risk for coronary calcium scores >100 (OR 1.80, 95% CI 0.87 to 3.78), but not in a statistically significant manner. After stratification for age at famine exposure, those exposed to severe famine as adolescents had higher risks (OR 3.47, 95% CI 1.00 to 12.07) for coronary calcium scores >100 than unexposed women, which remained significant after adjustment for several variables. Using different cut-off points of the Agatston score (0 and 300) led to similar results (data not shown).

Table 2.

The effect of famine exposure on coronary artery calcification as reflected by Agatston score

| Famine exposure | Agatston score (n, %) |

Crude |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <100, n=204 | >100, n=78 | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| All ages | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 104 (51.0) | 33 (42.3) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 72 (35.3) | 29 (37.2) | 1.27 | 0.71 to 2.27 | 0.42 | 1.08 | 0.58 to 1.99 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.53 to 1.92 | 0.99 |

| Severe | 28 (13.7) | 16 (20.5) | 1.80 | 0.87 to 3.78 | 0.11 | 1.63 | 0.76 to 3.46 | 0.21 | 1.74 | 0.79 to 3.84 | 0.17 |

| P for trend | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.24 | ||||||||

| Age 0–9 years | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 78 (51.3) | 18 (48.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 51 (33.6) | 13 (35.1) | 1.11 | 0.50 to 2.45 | 0.81 | 1.08 | 0.48 to 2.40 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.39 to 2.18 | 0.84 |

| Severe | 23 (15.1) | 6 (16.2) | 1.13 | 0.40 to 3.18 | 0.82 | 1.06 | 0.37 to 3.02 | 0.92 | 1.22 | 0.40 to 3.70 | 0.17 |

| P for trend | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.24 | ||||||||

| Age 10–17 years | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 26 (50.0) | 15 (36.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 21 (40.4) | 16 (39.0) | 1.32 | 0.53 to 3.28 | 0.55 | 1.07 | 0.41 to 2.80 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.53 to 1.92 | 0.99 |

| Severe | 5 (9.6) | 10 (24.4) | 3.47 | 1.00 to 12.07 | 0.05 | 3.65 | 1.01 to 13.31 | 0.04 | 4.62 | 1.16 to 18.43 | 0.03 |

| P for trend | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | ||||||||

Model 1: adjusted for age and pack-years smoked.

Model 2: adjusted for age, pack-years smoked, BMI, glucose, triglyceride, waist-to-hip ratio, systolic BP, cholesterol-to-HDL ratio.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ref, reference category.

Neither overall nor age-specific analyses indicated associations between famine exposure and calcification of mitral and/or aortic valves (table 3). Table 4 shows no statistically significant association between famine exposure and aortic calcification, although famine in young children (between 0 and 9 years of age) may later increase aortic calcium deposition (OR 2.64, 95% CI 0.69 to 4.10; p=0.10).

Table 3.

The effect of famine exposure on aortic and/or mitral valve calcification

| Famine exposure | Valve calcification (n, %) |

Crude |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=206 | Yes, n=80 | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| All ages | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 102 (49.5) | 37 (46.3) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 71 (34.5) | 32 (40.0) | 1.24 | 0.71 to 2.18 | 0.45 | 1.04 | 0.57 to 1.88 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.53 to 1.81 | 0.94 |

| Severe | 33 (16.0) | 11 (13.8) | 0.92 | 0.42 to 2.00 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.35 to 1.76 | 0.35 | 0.68 | 0.29 to 1.58 | 0.37 |

| P for trend | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.44 | ||||||||

| Age 0–9 years | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 74 (50.0) | 24 (55.8) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 51 (34.5) | 13 (30.2) | 0.79 | 0.37 to 1.69 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.32 to 1.58 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.30 to 1.54 | 0.35 |

| Severe | 23 (15.5) | 6 (14.0) | 0.80 | 0.29 to 2.21 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.22 to 1.78 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.18 to 1.71 | 0.56 |

| P for trend | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Age 10–17 years | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 28 (48.3) | 13 (35.1) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 20 (34.5) | 19 (51.4) | 2.05 | 0.82 to 5.08 | 0.12 | 1.66 | 0.64 to 4.30 | 0.99 | 1.65 | 0.52 to 4.65 | 0.34 |

| Severe | 10 (17.2) | 5 (13.5) | 1.08 | 0.31 to 3.79 | 0.91 | 1.06 | 0.29 to 3.92 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.20 to 3.16 | 0.74 |

| P for trend | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.37 | ||||||||

Model 1: adjusted for age and pack-years smoked.

Model 2: adjusted for age, pack-years smoked, BMI, glucose, triglyceride, waist-to-hip ratio, systolic BP, cholesterol-to-HDL ratio.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ref, reference category.

Table 4.

The effect of famine exposure on aortic calcification

| Famine exposure | Aortic calcification (n, %) |

Crude |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low, n=209 | High, n=77 | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| All ages | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 108 (51.7) | 31 (40.3) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 71 (34.0) | 32 (41.6) | 1.57 | 0.88 to 2.80 | 0.11 | 1.23 | 0.65 to 2.34 | 0.53 | 1.17 | 0.58 to 2.37 | 0.65 |

| Severe | 30 (14.4) | 14 (18.2) | 1.63 | 0.77 to 3.44 | 0.20 | 1.39 | 0.61 to 3.15 | 0.43 | 1.66 | 0.69 to 4.10 | 0.26 |

| P for trend | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.28 | ||||||||

| Age 0–9 years | Unexposed | 85 (53.1) | 13 (41.3) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| Moderate | 53 (33.1) | 11 (35.5) | 1.36 | 0.57 to 3.25 | 0.49 | 1.23 | 0.50 to 3.07 | 0.65 | 1.05 | 0.39 to 2.86 | 0.92 |

| Severe | 22 (13.8) | 7 (22.6) | 2.08 | 0.74 to 5.84 | 0.16 | 1.68 | 0.57 to 4.91 | 0.35 | 2.64 | 0.82 to 8.52 | 0.10 |

| P for trend | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| Age 10–17 years | |||||||||||

| Unexposed | 23 (46.9) | 18 (39.1) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 18 (36.7) | 21 (45.7) | 1.49 | 0.62 to 3.60 | 0.38 | 1.28 | 0.51 to 3.24 | 0.61 | 1.34 | 0.45 to 4.30 | 0.60 |

| Severe | 8 (16.3) | 7 (15.2) | 1.12 | 0.34 to 3.67 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 0.31 to 3.73 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.21 to 3.96 | 0.90 |

| P for trend | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.92 | ||||||||

Stratification based on smoking status did not modify the overall results at any calcification site (data not shown).

Discussion

Our study shows that severe famine exposure during childhood, specifically in adolescence, is associated with a threefold to fivefold risk increase to have at least moderate CAC in later life compared with those not exposed to famine. Although not statistically significant, famine exposure also tended to increase the risk of moderate-to-severe aortic calcification by approximately 60%, which was more pronounced in severe exposure to famine before the age of 9 years. Famine exposure was not related to mitral or aortic valve calcification.

To appreciate these findings some study aspects need to be addressed. Although unique for the combined availability of individual famine exposure data and thoracic CT images, the sample size was relatively small, limiting the statistical power. It is possible that effects that would have been seen in a larger study were missed, such as the effect of famine on extracoronary calcification. Nevertheless, we found an association between famine in adolescence and CAC. Also, our study population was restricted to postmenopausal women, so that generalising to men or to younger women remains speculative. However, our findings are in line with a previous report on the association between famine exposure in adolescence and late adulthood cardiovascular events,14 providing further insight into the possible underlying mechanism.

Despite a possible association between premenopausal metabolic factors and coronary and aortic calcifications,30 31 we chose not to adjust our analysis for these factors. As premenopausal and postmenopausal metabolic factors are strongly correlated,30 we believe that adjusting for both factors is not necessary and would even be misleading. By adjusting for postmenopausal factors, we indirectly took the premenopausal and the actual metabolic states at the time of calcium quantification into account. As previously shown, some traditional risk factors, such as lipid profiles,32 are exaggerated by menopause, so that accounting for these factors at the postmenopausal stage is important. However, the age at menopause itself seems not to be associated with coronary calcification.24

The choice of Agatston score of 100 as an arbitrary cut-off to rank the severity of coronary calcification might be a limitation of our study. However, despite ongoing controversies on the reliability of a particular cut-off to truly differentiate the risks of having cardiovascular diseases,33 34 we used the most commonly applied cut-off. A score above 100 has repeatedly been reported to be associated with an approximately threefold to sevenfold increased risk of coronary events or cardiovascular death35 36; therefore, our choice of cut-off seems justifiable. Moreover, we found that using different cut-offs did not lead to different results.

A major strength of our study was the use of the unique circumstances of the Dutch famine. As previously described,25 the Dutch famine occurred within an approximately 6 month period between the end of 1944 and mid-1945, when food supplies in the Netherlands acutely and dramatically dropped to 400–800 kcal/day due to food transport bans and severe winter weather. After that period, the situation quickly improved, abruptly ending the famine. This situation allowed us to investigate the effects of postnatal undernutrition on health as a ‘natural experiment,’ rather than purely observational and to study the welldocumented, acute nature of the undernutrition.

Although the measurement of famine exposure by recall may have some drawbacks related to its subjective nature and propensity of misclassification, we believe that if anything had occurred, it would have happened at random and only underestimate the observed effects. On the other hand, the use of individual data on famine exposure rather than grouping populations according to place of residence or time is a strength of our study since we used a more precise exposure measurement. As described previously, our exposure classification agrees with rationing practices at that time, in which individual calorie amounts were based on age. Young children (1–3 years) were relatively protected from the famine and received about 50%, whereas adults received about 25% of the distributed calorie amounts at the start of the famine.25 These historical facts are reflected by our data, such that the older the women were at the start of the famine, the higher the proportion of women who reported having been exposed to famine. This may be considered in support of the quality of our exposure data. We performed blinded and objective measurements of the calcium content using the CT scan, so that differential scan measurement by exposure knowledge is excluded as an explanation of our findings.

CACs are thought to be a reflection of the burden of intima lesions; hence, coronary atherosclerosis.37 For aortic calcifications, it is not clear that these always reflect atherosclerosis.38 Most of the pathological studies have found a substantial amount of aortic calcifications located in the tunica media and not in the intima. Data even suggest that media calcifications develop earlier and more extensively in the aorta compared with intima calcifications.39 Also for valve calcifications, the biology is now thought to be more on longstanding mechanical stress than on inflammation.40 Changes in valve tissue have been observed in persons who do not exhibit features of atherosclerosis, indicating that early stages of cardiac valve calcification involve mechanisms different from CAC.40

To our knowledge, there has been no previous study addressing an association between childhood famine exposure and vascular or valve calcifications in later life. Most studies linking malnutrition and coronary or valve calcification were conducted on patients with end-stage renal disease.41 Such patients are reported to experience a malnutrition–inflammation–atherosclerosis/calcification syndrome, which is a strong predictor for cardiovascular death. Although a full assessment of the mechanisms underlying the association between undernutrition and coronary artery or valve calcification is beyond the scope of our study, the findings in patients with renal diseases suggest that a similar interaction between malnutrition, increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and calcification or atherosclerosis may play a role.42 43 This suggests that the protective effect of caloric restriction in adulthood and animals on atherosclerosis and metabolic syndromes44 45 may not be readily translated to undernutrition in early life. Caloric restriction in different periods of life probably has different effects on atherosclerosis development, as suggested by findings from two studies on the Dutch famine which showed that famine exposure during adolescence increased the risk for cardiovascular events,14 whereas prenatal famine exposure did not.46

Our findings suggest that the critical period determining future development of cardiovascular diseases may extend beyond fetal life and infancy. Previous studies have demonstrated the role of early life nutrition in the development of chronic diseases in adulthood. For example, the Biafran famine study showed that fetal–infant undernutrition is associated with an increased risk of hypertension and impaired glucose tolerance in adulthood,47 similar to what was found in the Chinese great famine study.48 Although few studies have evaluated the effect of postnatal events per se on health in later life, it seems that maintaining balanced nutrition in later childhood is also crucial, as suggested by the detrimental effects of weight fluctuation or ‘yoyo’ dieting in young adulthood on coronary heart disease.17 Our study only addresses one of the possible mechanisms of the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases by childhood famine exposure. The findings are consistent with a previous finding of the association between famine exposure in adolescence and clinical cardiovascular disease. Hence, our findings warrant further studies into the role of calcium deposition in the relationship between acute famine and later life cardiovascular disease.

In conclusion, famine exposure in childhood, especially during adolescence, may be associated with a higher risk of CAC in late adulthood. There seems to be no clear association between childhood famine exposure and cardiac valve or aortic calcification.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NSI, SGE and CSPMU were involved in conceptualisation and design of the study. YTvdS, AFMvA, TJR, PAdJ, AR and SGE were responsible for data collection. NSI analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. YTvdS, AFMvA, TJR, PAdJ, AR, DEG, CSPMU and SGE provided constructive feedback on each draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript

Funding: The original study for which coronary calcium was measured was supported by grant 2100.0078 from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Utrecht.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Stratified analysis of the effect of famine in childhood on coronary artery calcification based on smoking exposure is available by emailing the corresponding author (NSI).

References

- 1.Hughes BB, Kuhn R, Peterson CM, et al. Projections of global health outcomes from 2005 to 2060 using the international futures integrated forecasting model. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:478–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Djärv T, Wikman A, Lagergren P. Number and burden of cardiovascular diseases in relation to health-related quality of life in a cross-sectional population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJP, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet 1986;327:1077–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ, et al. The relation of small head circumference and thinness at birth to death from cardiovascular disease in adult life. BMJ 1993;306:422–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein C, Fall C, Kumaran K, et al. Fetal growth and coronary heart disease in South India. Lancet 1996;348:1269–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms elicited by nutrition in early life. Nutr Res Rev 2011;24:198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leon DA, Lithell HO, Vågerö D, et al. Reduced fetal growth rate and increased risk of death from ischaemic heart disease: cohort study of 15 000 Swedish men and women born 1915–29. BMJ 1998;317:241–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hales CN, Barker DJP. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull 2001;60:5–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attig L, Gabory A, Junien C. Early nutrition and epigenetic programming: chasing shadows. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2010;13:284–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berends LM, Fernandez-Twinn DS, Martin-Gronert MS, et al. Catch-up growth following intra-uterine growth-restriction programmes an insulin-resistant phenotype in adipose tissue. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:1051–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evelein AM, Visseren FL, van der Ent CK, et al. Excess early postnatal weight gain leads to thicker and stiffer arteries in young children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:794–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fall CH, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, et al. Adult metabolic syndrome and impaired glucose tolerance are associated with different patterns of BMI gain during infancy: data from the New Delhi birth cohort. Diabetes Care 2008;31:2349–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris SA, Osmond C, Gigante D, et al. Size at birth, weight gain in infancy and childhood, and adult diabetes risk in five low- or middle-income country birth cohorts. Diabetes Care 2012;35:72–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Abeelen AFM, Elias SG, Bossuyt PMM, et al. Cardiovascular consequences of famine in the young. Eur Heart J 2012;33:538–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portrait F, Teeuwiszen E, Deeg D. Early life undernutrition and chronic diseases at older ages: the effects of the Dutch famine on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:711–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sparén P, Vågerö D, Shestov DB, et al. Long term mortality after severe starvation during the siege of Leningrad: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2004;328:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dulloo AG, Jacquet J, Seydoux J, et al. The thrifty ‘catch-up fat’ phenotype: its impact on insulin sensitivity during growth trajectories to obesity and metabolic syndrome. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(Suppl 4):S23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondos GT, Hoff JA, Sevrukov A, et al. Electron-beam tomography coronary artery calcium and cardiac events: a 37-month follow-up of 5635 initially asymptomatic low- to intermediate-risk adults. Circulation 2003;107:2571–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham G, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, et al. Impact of coronary artery calcification on all-cause mortality in individuals with and without hypertension. Atherosclerosis 2012;225:432–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gondrie MJ, van der Graaf Y, Jacobs PC, et al. The association of incidentally detected heart valve calcification with future cardiovascular events. Eur Radiol 2011;21:963–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owens DS, Budoff MJ, Katz R, et al. Aortic valve calcium independently predicts coronary and cardiovascular events in a primary prevention population. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:619–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Budoff MJ, Nasir K, Katz R, et al. Thoracic aortic calcification and coronary heart disease events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis 2011;215:196–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boker LK, van Noord PA, van der Schouw YT, et al. Prospect-EPIC Utrecht: study design and characteristics of the cohort population. European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:1047–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atsma F, Bartelink ML, Grobbee DE, et al. Reproductive factors, metabolic factors, and coronary artery calcification in older women. Menopause 2008;15:899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger G, Sandstead H, Drummond J. Malnutrition and starvation in western Netherlands, September 1944 to July 1945. Part I and II. The Hague: General State Printing, 1948 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;15:827–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hecht HS. Subclinical atherosclerosis imaging comes of age: coronary artery calcium in primary prevention. Curr Opin Cardiol 2012;27:508–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabour S, Atsma F, Rutten A, et al. Multi detector-row computed tomography (MDCT) had excellent reproducibility of coronary calcium measurements. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:572–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Abeelen AF, Elias SG, Bossuyt PM, et al. Famine exposure in the young and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood. Diabetes 2012;61:2255–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Chang Y, et al. Premenopausal risk factors for coronary and aortic calcification: a 20-year follow-up in the healthy women study. Prev Med 2007;45:302–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuller LH, Matthews KA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Coronary and aortic calcification among women 8 years after menopause and their premenopausal risk factors: the healthy women study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:2189–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torng PL, Su TC, Sung FC, et al. Effects of menopause and obesity on lipid profiles in middle-aged Taiwanese women: the Chin-Shan community cardiovascular cohort study. Atherosclerosis 2000;153:413–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nucifora G, Bax JJ, van Werkhoven JM, et al. Coronary artery calcium scoring in cardiovascular risk assessment. Cardiovasc Ther 2011;29:e43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tota-Maharaj R, Blaha MJ, McEvoy JW, et al. Coronary artery calcium for the prediction of mortality in young adults 75years old. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2955–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA 2010;303:1610–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erbel R, Möhlenkamp S, Moebus S, et al. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf recall study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sage AP, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Regulatory mechanisms in vascular calcification. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:528–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kälsch H, Lehmann N, Berg MH, et al. Coronary artery calcification outperforms thoracic aortic calcification for the prediction of myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality: the Heinz Nixdorf recall study. Eur J Prevent Cardiol 2013. [epub ahead of print 6 Mar 2013]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amann K. Media calcification and intima calcification are distinct entities in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karwowski W, Naumnik B, Szczepanski M, et al. The mechanism of vascular calcification—a systematic review. Med Sci Monit 2012;18:RA1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srivaths PR, Silverstein DM, Leung J, et al. Malnutrition-inflammation-coronary calcification in pediatric patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 2010;14:263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stenvinkel P, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B, et al. Are there two types of malnutrition in chronic renal failure? Evidence for relationships between malnutrition, inflammation and atherosclerosis (MIA syndrome). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000;15:953–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang AY, Woo J, Lam CW, et al. Associations of serum fetuin-A with malnutrition, inflammation, atherosclerosis and valvular calcification syndrome and outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:1676–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi KM, Han KA, Ahn HJ, et al. The effects of caloric restriction on fetuin-A and cardiovascular risk factors in rats and humans: randomized controlled trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fontana L, Meyer TE, Klein S, et al. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:6659–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lumey LH, Martini LH, Myerson M, et al. No relation between coronary artery disease or electrocardiographic markers of disease in middle age and prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine of 1944–5. Heart 2012;98:1653–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hult M, Tornhammar P, Ueda P, et al. Hypertension, diabetes and overweight: looming legacies of the biafran famine. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e13582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang PX, Wang JJ, Lei YX, et al. Impact of fetal and infant exposure to the Chinese great famine on the risk of hypertension in adulthood. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e49720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.