Abstract

Introduction

Letrozole is being used as an alternative to clomiphene citrate in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) requiring ovulation induction. Berberine, a major active component of Chinese herbal medicine rhizoma coptidis, has been used to improve insulin resistance to facilitate ovulation induction in women with PCOS but there is no study reporting the live birth or its potential as a complementary treatment to letrozole. We aim to determine the efficacy of letrozole with or without berberine in achieving live births among 660 infertile women with PCOS in Mainland China.

Methods and analysis

This study is a multicentre randomised, double-blind trial. The randomisation scheme is coordinated through the central mechanism and stratified by the participating site. Participants are randomised into one of the three treatment arms: (1) letrozole and berberine, (2) letrozole and berberine placebo, or (3) letrozole placebo and berberine. Berberine is administered three times a day (1.5 g/day) for up to 24 weeks, starting on day 1 after a spontaneous period or a withdrawal bleeding. Either letrozole or letrozole placebo 2.5 mg is given daily from day 3 to day 7 of the first three cycles and the dose is increased to 5 mg/day in the last three cycles, if not pregnant. The primary hypothesis is that the combination of berberine and letrozole results in a significantly higher live birth rate than letrozole or berberine alone.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine. Study findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01116167.

Keywords: REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is characterised by anovulation, hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries (PCOs) on scanning and is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age as it affects 5–10% of premenopausal women.1 Insulin resistance has been implicated in the pathogenesis of anovulation and infertility in PCOS and abnormalities in insulin action have been noted in a variety of reproductive tissues from women with PCOS and may explain the pleiotropic presentation and multiorgan involvement of the syndrome.2

The first-line medical treatment for ovulation induction in PCOS women is clomiphene citrate (CC), which can result in an ovulation rate of 60–85% but a conception rate of only about 20%.3–6 Antioestrogenic effects of CC on the endometrium and cervix mucus are thought to cause the low conception rate.7 Also, CC may have a number of side effects including hot flushes, breast discomfort, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, nervousness, sleeplessness, headache, mood swings, dizziness, hair loss and disturbed vision.6 Letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, traditionally applied for oestrogen-dependent carcinoma, has been used for ovulation induction for about a decade.8 9 The effectiveness of letrozole versus CC for ovulation induction has been reviewed by two meta-analyses.10 11 In both meta-analyses that included six randomised controlled trials, it was concluded that even though letrozole was associated with a lower number of mature follicles per cycle, there was no significant difference in the ovulation rate per cycle or the pregnancy, multiple pregnancy or miscarriage rates between letrozole and CC. No difference was found in the live birth rate, although it was only assessed in one meta-analysis.11

Based on the above two meta-analyses, letrozole appears to be at least as effective as CC in ovulation induction with some potential advantages over CC. Although side effects reported by patients in the group receiving CC were higher, while no complication was noted in the group receiving letrozole,12 large sample sized clinical trials are still needed. As far as we know, two large randomised multicentre studies, the Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II (PPCOSII)13 trial and the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS)14 trial are ongoing and can provide definitive evidence for pregnancy outcome with the use of CC versus letrozole.

Insulin sensitising agents are commonly used as adjunctive medications for women with PCOS and metformin is widely chosen.15 Although a newly published meta-analysis showed that there was no evidence that metformin improved live birth rates in combination with CC (pooled OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.56; 7 trials and 907 women), the clinical pregnancy rates were higher for the combination of metformin and CC than CC alone (pooled OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.96; 11 trials and 1208 women).15 Furthermore, metformin was associated with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal disturbances than placebo (pooled OR 4.27, 95% CI 2.4 to 7.59; 5 trials and 318 women), which hampered its clinical compliance with high dropout rates.16

Recent studies suggest that several Chinese herbal medicines could be beneficial as an adjunct to the conventional medical management of PCOS, but the evidence is limited due to the poor methodology of existing trials.17 Berberine, the major active component of rhizoma coptidis, exists in a number of medicinal plants and displays a broad array of pharmacological effects.18 In Chinese medicine, berberine has a long history for its antidiabetic effect. A recent meta-analysis compared different oral hypoglycaemics including metformin, glipizide or rosiglitazone with berberine, and found no priority over glycaemic control but a mild antidyslipidemic effect following berberine.19 The mechanism of its hypolipidemic effect was studied using human hepatoma cells. Berberine acts differently from that of statin drugs as it could upregulate low-density lipoprotein receptor expression independent of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins, but dependent on extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation.20

A series of basic research also implicated that berberine could have beneficial effects in women with PCOS. In insulin-resistant theca cells, berberine increased glucose transporter type 4, decreased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ mRNA levels, increased glucose uptake, and reduced insulin resistance.21–23 These results indicate that berberine can improve insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant ovary theca cells. In ovary granulosa cells, berberine was found to reduce the ovarian oestrogenic responsiveness by their insulin-sensitising effects similar to metformin, but different from thiazolidinedione.24 Berberine could also alleviate the degree of insulin resistance and androgen synthesis in cultured insulin-resistant ovaries, indicating that berberine may have a favourable effect on fertility in women with PCOS.25

However, there is only one study investigating the effect of berberine in women with PCOS.26 Eighty-nine Chinese women with PCOS with insulin resistance were randomised to one of the three treatment groups: berberine+cyproterone acetate (CPA; n=31), metformin+CPA (n=30) and placebo+CPA (n=28) for 3 months. The author concluded that berberine showed similar metabolic effects on the amelioration of insulin sensitivity and the reduction of hyperandrogenaemia, when compared to metformin. Berberine also appeared to have a greater effect on the changes in body composition and dyslipidemia. That study was limited by its small sample size, incomplete description of the methodology and use of surrogate outcomes (anthropometric measures and hormonal and metabolic value changes). There is also an ongoing trial (NCT01138930) testing the efficacy of berberine on insulin resistance in women with PCOS as measured by a hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp. Berberine was thought to be safe during clinical use.19 The side effects were commonly gastrointestinal discomforts including constipation, diarrhoea, nausea and abdominal distension. Constipation was one of the most common gastrointestinal discomforts, but it is predictable since berberine had a long history of being used to treat diarrhoea in China.

We aim to determine the efficacy of letrozole with or without berberine in achieving live births among women with PCOS seeking pregnancy in Mainland China. The primary hypothesis is that the combination of berberine and letrozole results in a significantly higher live birth than letrozole or berberine alone. We report the study design of our ongoing study.

Materials and methods

This is a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled clinical trial. A total of 660 women with PCOS seeking pregnancy (or 220 per each treatment arm) will be enrolled at one of 18 participating sites and randomly assigned to three treatment arms.

Written informed consent will be obtained from each patient prior to her participation in the study. The trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01116167).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome is that combination of berberine and letrozole results in a significantly higher live birth than letrozole or berberine alone.

Secondary outcomes are the adjunctive use of berberine to letrozole that has an additive effect on the following:

Ovulation rate: Patients will undergo serum progesterone test at day 22 of each treatment cycle. Progesterone >3 ng/mL will be considered as ovulation.

Ongoing pregnancy rate at around gestation 8–10 weeks. Pregnancy will be confirmed, if suspected, by the measurement of serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Pregnancies will be followed by the serial rise of serum hCG and ultrasound will be utilised to determine the location of the pregnancy and the number of implantation sites. Participants who conceive will be followed through the study until the pregnancy has advanced to the point of determining the number of gestational sacs, their location and fetal viability as determined by visualisation of fetal heart motion by ultrasonography.

Multiple pregnancy rates.

Miscarriage rate: Loss of an intrauterine pregnancy before 20 completed weeks of gestation.

Other pregnancy complications such as early pregnancy loss, gestational diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension and birth of small-for-gestational-age babies.

Infant outcome: We will review pregnancy and birth records to document neonatal morbidity and mortality and the presence of fetal anomalies.

Changes in the metabolic profile: Fasting glucose and insulin concentrations, cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). The blood sample for the tests will be drawn at the baseline visit and at the end of the treatment visit.

Changes in hormonal profile: Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), Luteinising hormone (LH), total testosterone (T), sex hormone-binding globulin and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. The fasting blood sample for the tests will be drawn at the baseline visit and at the end of the treatment visit at menstrual cycle days 3–7.

Side effect: The patient will be asked to record adverse events and report to the coordinator during each visit.

Study population

Women with PCOS who desire pregnancy are eligible if they fulfil the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Age between 20 and 40 years

Confirmed diagnosis of PCOS according to the Rotterdam 2003 criteria (2 of 3)

Oligo-ovulation or anovulation

Clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism

PCOs and exclusion of other aetiologies (congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumours and Cushing's syndrome)

At least one patent tube and normal uterine cavity shown by hysterosalpingogram, hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography or diagnostic laparoscopy within 3 years

Sperm concentration 15×106/mL and progressive motility (grades a* and b**) ≥40%. *Grade a: rapid progressive motility (sperm moving swiftly, usually in a straight line). **Grade b: slow or sluggish progressive motility (sperm may be less linear in their progression)

History of 1 year of infertility

Exclusion criteria

Use of hormonal drugs or other medications including Chinese herbal prescriptions in the past 3 months

Patients with known severe organ dysfunction or mental illness

Pregnancy, postabortion or postpartum within the past 6 weeks

Breastfeeding within the past 6 months

Not willing to give written consent for the study

Written informed consent will be obtained from each woman prior to participation in this study.

Intervention

Eligible patients will be randomised into one of three arms: (1) letrozole and berberine, (2) letrozole and berberine placebo, and (3) letrozole placebo and berberine. Anovulatory patients will have a withdrawal bleed induced with a course of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate before the initiation of study medication. Each participant will receive a medication package on a monthly basis that consists of a monthly supply of berberine capsules or placebo capsules and one or two packages of pills (letrozole or letrozole placebo, 1 package per month for the first 3 months, and 2 packages per month for the next 3 months). Berberine or berberine placebo will be administrated orally at a daily dose of 1.5 g for 6 months (26). Patients will receive an initial dose of 2.5 mg (1 tablet) of letrozole or one tablet of letrozole placebo on days 3–7 of the first three treatment cycles and increased to 5 mg of letrozole (2 tablets) or two tablets of letrozole placebo on days 3–7 of the last three treatment cycles if not pregnant. Berberine and berberine placebo were produced by Renhetang Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, China. Letrozole and letrozole placebo were produced by Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co, Ltd, China.

Study specific visits and procedures

Each specific visit and measurement is summarised in table 1. Baseline measures include fasting FSH, LH, total T, oestradiol (E2), glucose and insulin concentrations, cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-C, LDL-C and height, weight, hip, waist measurements, and vital signs. Also, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) syndromes of each patient will be accessed with the aim to associate the TCM diagnosis to the study endpoint outcome on baseline visit. Syndrome differentiation in TCM is the comprehensive analysis of clinical information gained by the four main diagnostic TCM procedures: observation, listening, questioning and pulse taking.27 In PCOS, patients are empirically categorised into four categories diagnosed by the local Chinese doctors: (1) spleen deficiency and phlegm-dampness syndrome, (2) kidney deficiency and liver qi-stagnation syndrome, (3) kidney deficiency and blood stasis syndrome, and (4) phlegm-dampness and blood stasis syndrome.28 The TCM diagnosis will be made by an experienced TCM doctor in each participating site according to a standard questionnaire.

Table 1.

Overview of the study visits

| Screening visit | Baseline visit | Monthly visit 1 | Monthly visit 2 | Monthly visit 3 | Monthly visit 4 | Monthly visit 5 | Monthly visit 6 | End of treatment visit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Sign consent | × | ||||||||

| Urine pregnancy test | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| Physical examination and history | × | × | |||||||

| Transvaginal ultrasound | × | × | × | ||||||

| Semen analysis | × | ||||||||

| Hysterosalpingogram or sonohysterogram | × | ||||||||

| Safety eligibility tests | × | × | × | ||||||

| Fasting phlebotomy for study parameters | × | × | × | ||||||

| Progesterone level | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| Quality of life measures | × | × | × | ||||||

| Assess adverse events | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

| Record concomitant medications | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

All baseline measures will be repeated in all participants at the end of all visits. Safety tests will be repeated during monthly visit 3 and end of treatment visit. Blood samples will be collected and shipped to the core laboratory.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

The randomisation will be performed through a web-based randomisation system (http://210.76.97.192:8080/cjbyj) operated by an independent data centre—the Institute of Basic Research in Clinical Medicine (IBRCM), China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences. Recruited participants will be allocated randomly into one of the three groups in a ratio of 1:1:1. The identification code and random number, which are unique for each participant, will be given by a web-based system, also produced by IBRCM. Participants, investigators and physicians taking care of participants will be blinded to the assignment.

Data entry and quality control of data

Case report forms (CRFs) have been developed for data entry and an electronic version is implemented in a web-based data management system (http://210.76.97.192:8080/cjbyj).

Quality control of data will be handled at three different levels. The first level is the real time logical and range checking built into the web-based data entry system. The investigators at the participating sites are required to ensure data accuracy as the first defence. The second is the remote data monitoring and validation that is the primary responsibility of the study data manager and programmer. The data manager will conduct monthly comprehensive data checks, as well as regular manual checks (within the database system). Manual checks will identify more complicated and less common errors. The data manager will query sites until each irregularity is resolved. The third level of quality control will be the site visits, where data in our database will be compared against source documents. Identified errors will be resolved between the data coordination centre and clinical sites. The visits will assure data quality and patient protection.

Participation timeline

This trial was started on October 2009 and the first recruitment was on 15 May 2010. The intervention will take up to 6 months and the patient will come to the hospital to see the doctor at least once a month to get progesterone test and medication.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

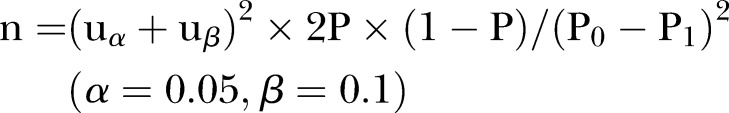

The sample size calculation is based on the live birth rate. The previous study showed that the live birth rate of letrozole was 22%,29 we hypothesised that a combination of letrozole and berberine can increase the live birth rate to 30%. According to the sample size of the estimation formula30

|

it is estimated that a sample size of 220 participants per group will be required, considering a 20% dropout. Intention-to-treat analysis will be applied to minimise bias due to dropouts.

Primary efficacy analysis will be performed by comparing the treatment groups with respect to the primary outcome of live birth using the Pearson χ2 test.

For the secondary supportive analysis, we will fit a logistic regression model to compare the treatment arms with respect to the primary outcome of live birth, adjusting for other factors such as randomisation stratification of study site and prior exposure to study medications. The analysis of other secondary outcomes measured over time will entail the application of statistical methods that have been developed for correlated data since repeated observations will be made over time on each individual. For secondary outcomes such as hormone levels, a linear mixed-effects model will be fit where the main independent variables will be treatment group, time and their interaction as well as the designed randomisation stratification factors as covariates. Cox proportional hazards models and a Kaplan-Meier method will be applied to compare time to pregnancy in the treatment groups.

Adverse events will be categorised and percentage of patients experiencing adverse events and serious adverse events in this trial will be documented. χ2 Tests will be performed to examine differences in the proportion of total, and categories of adverse events within each treatment arm. Unblinding of treatments will take place after all participants have delivered or reported final outcomes or when there are medical emergencies.

Summary

The present study has several distinctive features. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial assessing reproductive effects of berberine on women with PCOS using the live birth rate as the primary outcome, instead of surrogate outcomes such as ovulation and pregnancy rates or metabolic index such as insulin resistance and glucolipid profiles. The present trial uses a combination therapy of letrozole and berberine. Effects of berberine on ovulation, corpus luteum, implantation and obstetrics complications as well as teratogenic effects at different stages of reproductive process will be assessed in the present study. Compared with metformin, berberine has less and milder side effects and ameliorating effects on lipid metabolism, which is also a stigma with women with PCOS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: WX, LH, JL and YL developed the study protocol. YL, HK, WS, HM and YZ coordinated the study. WX and LH will oversee enrolment and data collection. YL drafted the manuscript in collaboration with ES-V and EHYN. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by: (1) the National Public Welfare Projects for Chinese Medicine (200807021), (2) the Heilongjiang Province Foundation for Outstanding Youths (JC200804) and (3) the Intervention for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Based on Traditional Chinese Medicine Theory—‘TianGui Shi Xu’ (2011TD006).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (2009LL-001-02).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We state that all samples, genetic or proteinic and data are available within scientists within China.

References

- 1.Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet 2007;370:685–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauli JM, Raja-Khan N, Wu X, et al. Current perspectives of insulin resistance and polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabet Med 2011;28:1445–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickey RP, Taylor SN, Curole DN, et al. Incidence of spontaneous abortion in clomiphene pregnancies. Hum Reprod 1996;11:2623–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorlitsky GA, Kase NG, Speroff L. Ovulation and pregnancy rates with clomiphene citrate. Obstet Gynecol 1978;51:265–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gysler M, March CM, Mishell DR, Jr, et al. A decade's experience with an individualized clomiphene treatment regimen including its effects on the postcoital test. Fertil Steril 1982;37:161–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, et al. Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007;356:551–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonen Y, Casper RF. Sonographic determination of an adverse effect of clomiphene citrate on endometrial growth. Hum Reprod 1990;5:670–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Aromatase inhibition: a novel method of ovulation induction in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Reprod Technol 2000;10:244–7 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Use of an aromatase inhibitor for induction of ovulation in patients with an inadequate response to clomiphene citrate. Fertil Steril 2001;75:305–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He D, Jiang F. Meta-analysis of letrozole versus clomiphene citrate in polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Biomed Online 2011;23:91–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misso ML, Wong JL, Teede HJ, et al. Aromatase inhibitors for PCOS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2012;18:301–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nahid L, Sirous K. Comparison of the effects of letrozole and clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Minerva Ginecol 2012;6:253–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Brzyski RG, et al. ; NICHD Reproductive Medicine Network The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II (PPCOS II) trial: rationale and design of a double-blind randomized trial of clomiphene citrate and letrozole for the treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:470–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond MP, Mitwally M, Casper R, et al. ; NICHD Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network Estimating rates of multiple gestation pregnancies: sample size calculation from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2011;32:902–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang T, Lord JM, Norman RJ, et al. Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:CD003053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinawat S, Buppasiri P, Lumbiganon P, et al. Long versus short course treatment with metformin and clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction in women with PCOS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD006226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Li T, Zhou L, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for subfertile women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;9:CD007535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birdsall TC, Kelly GS. Berberine: therapeutic potential of an alkaloid found in several medicinal plants. Altern Med Rev 1997;2:94–103 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong H, Wang N, Zhao L, et al. Berberine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:591654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong W, Wei J, Abidi P, et al. Berberine is a novel cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism distinct from statins. Nat Med 2004;10:1344–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X. Theca insulin resistance: dexamethasone induction and berberine intervention. Fertil Steril 2010;94:s197 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L, Li W, Han F, et al. Berberine reduces insulin resistance induced by dexamethasone in theca cells in vitro. Fertil Steril 2011;95:461–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao L, Li W, Kuang HY. Of berberine and puerarin on dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance in porcine ovarian thecal cells. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2009;29:623–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu XK, Yao JP, Hou LH, et al. Berberine improves insulin resistance in granulosa cells in a similar way to metformin. Fertil Steril 2006;86:459–60 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XX, Li W, Liu YC. Controlling effect of berberine on in vitro synthesis and metabolism of steroid hormones in insulin resistant ovary. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2010;30:161–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei W, Zhao H, Wang A, et al. A clinical study on the short-term effect of berberine in comparison to metformin on the metabolic characteristics of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;166:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang M, Lu C, Zhang C, et al. Syndrome differentiation in modern research of traditional Chinese medicine. J Ethnopharmacol 2012;140:634–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou LH, Wang YT, Wu XK. Today's gynecology of Chinese medicine. 1st edn People's Medical Publishing House, 2011, ISBN 978-7-117-13644-0/R.13645 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2008;23:462–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu JP. Clinical research methodology for evidence-based Chinese medicine. People's Medicine Publishing House, 2006; ISBN:9787117074193 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.