Abstract

Objectives

Against a backdrop of rising levels of obesity, we describe and estimate associations of body mass index (BMI), age and gender with time to revision for participants undergoing primary total hip (THR) or knee (TKR) replacement in the UK.

Design

Population-based cohort study.

Setting

Routinely collected primary care data from a representative sample of general practices, including linked data on all secondary care events.

Participants

Population-based cohort study of 63 162 patients with THR and 54 276 with TKR in the UK General Practice Research Database between 1988 and 2011.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Risk of THR and TKR revision associated with BMI, age and gender, after adjusting for the competing risk of death.

Results

The 5-year cumulative incidence rate for THR was 2.2% for men and 1.8% for women (TKR 2.3% for men, 1.6% for women). The adjusted overall subhazard ratio (SHR) for patients with THR undergoing subsequent hip revision surgery, with a competing risk of death, were estimated at 1.020 (95% CI 1.009 to 1.032) per additional unit (kg/m2) of BMI, 1.23 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.38) for men compared with women and 0.970 (95% CI 0.967 to 0.973) per additional year of age. For patients with TKR, the equivalent estimates were 1.015 (95% CI 1.002 to 1.028) for BMI; 1.51 (95% CI 1.32 to 1.73) for gender and 0.957 (95% CI 0.951 to 0.962) for age. Morbidly obese patients with THR had a 65.5% increase (95% CI 15.4% to 137.3%, p=0.006) in the subhazard of revision versus the normal BMI group (18.5–25). The effect for TKR was smaller (a 43.9% increase) and weaker (95% CI 2.6% to 103.9%, p=0.040).

Conclusions

BMI is estimated to have a small but statistically significant association with the risk of hip and knee revision, but absolute numbers are small. Further studies are needed in order to distinguish between effects for specific revision surgery indications.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The large sample size of the General Practice Research Database (GPRD; over 5% of the UK general practice population) enables population-level inferences to be made.

The statistical methods explicitly account for the competing risk of death which has a much higher event rate than the event of interest (total hip or knee replacement) in this patient group.

GPRD data do not have directly linked information detailing the reasons for being referred for surgery, so we were unable to establish an exact indication.

Introduction

Total joint replacement of the hip and knee are well established as interventions for those suffering with end-stage osteoarthritis (OA) of the lower limb, with OA being the most frequent indication for total hip (THR) or knee replacement (TKR) in the UK1 (over 90% for hips and over 95% for knees). Yet hip and knee prostheses do not necessarily continue to function effectively for the lifetime of the patient.1 2 Many traditional metal-on-polyethylene implants are likely to require revision surgery due to wear after 20 years of use due to wear characteristics and peri-prosthetic loosening. As a consequence, elective THR and TKR procedures have until relatively recently been indicated mainly in older patients, but even prostheses which make use of the latest technological developments (eg, unicondylar knee prostheses) are not yet routinely recommended for use in younger patients.

A further dimension is added by the increasing prevalence of obesity in western populations, with clinicians in some cases considering patients too obese to undergo surgery,3 4 partly due to the perceived increase in risk of both peri-operative and postoperative complications. There have also been examples of obese and/or morbidly obese patients experiencing restricted access to hip replacement surgery in some parts of the UK5–7 where local healthcare planners have had similar concerns.

Revision procedures involve a surgical intervention to correct a prosthesis which is not functioning properly. Such operations are more costly than the original replacement procedure8 9 and are often more complex, with a higher level of risk to the patient. Population-based estimates of the time from primary surgery to a revision procedure are of importance to orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists, healthcare providers, policymakers and patients. Registry data, both in the UK1 and internationally,10 11 have been used extensively to estimate time to revision.12 Such data have been used previously to model prosthesis survival time in order to assess which specific demographic, clinical and prosthesis-specific factors are associated with time to failure.13 14

Over the 12 months to April 2011, there were over 178 000 THR and TKR operations recorded in the National Joint Registry (NJR) for England and Wales.1 The NJR began recording data in 2003, and although it now contains virtually all replacements carried out in England and Wales, the maximum follow-up is currently less than 10 years. The registry contains complete data on many variables, including age and gender, but body mass index (BMI) is recorded in approximately 61% of participants undergoing hip replacement (62% for knee). We chose to use data from a primary care database with long follow-up and UK-wide coverage.

The primary aim of this study was to use data from the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) to produce population-based estimates for the association of BMI, age and gender with the time to revision surgery in the long term following THR or TKR.

Method

Participants

We used data from the GPRD. The GPRD comprises the entire computerised medical records of a sample of patients attending general practitioners (GPs) in the UK covering a population of 6.5 million patients from over 600 contributing practices chosen to be representative of the wider UK population.15 GPs in the UK play a key role in the delivery of healthcare by providing primary care and referral to specialist hospital services. Patients are registered with one practice that stores medical information from primary care and hospital attendances. The GPRD has recently become part of the new Clinical Practice Research Datalink which is administered by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

The GPRD records contain all clinical and referral events in both primary and secondary care in addition to comprehensive demographic information, prescription data and hospital admissions. Data are stored using read codes for diseases that are cross-referenced to the International Classification of Diseases-9. Read codes are used as the standard clinical terminology system within UK primary care. Only practices that pass quality control are used as part of the GPRD database. Deleting or encoding personal and clinical identifiers ensures the confidentiality of information in the GPRD. The GPRD comprises entire general practice populations rather than probability-based samples of patients.

We identified all patients in the database with a diagnosis code for total hip or knee arthroplasty from the beginning of 1988 until August 2011. We then identified any secondary (revision) hip or knee operations for these patients which occurred subsequent to the primary operation. The list of Read codes used to identify the primary and revision operations were independently reviewed by different clinicians and a consensus list agreed between them. Deaths recorded within the GPRD were also identified. The date of the first incidence of a patient's hip or knee replacement was used as the start time. The event of interest in all time-to-event models was the first recorded revision operation. Censoring events were the end of study date (11 August 2011) or the transfer of a patient out of the GPRD for any reason other than death. Death from any cause was treated as a competing risk in the primary analysis. Patients were included in the analysis if aged 18 years or over at the time of the replacement operation. Participant demographics including age, gender, preoperative BMI, smoking and drinking status were collated, in addition to information on comorbid conditions.

Analysis

We used the competing risks regression methods of Fine and Gray16 to estimate the effects of a participant's BMI, age and gender on the time to revision of a prosthesis implanted during THR or TKR operation. The substantive event of interest was the first incidence of revision surgery, with all-cause mortality separately identified as a competing risk. The rationale for using competing risks regression is that methods which treat death as just another censoring event may overestimate risk for an event of interest, especially in an older population.17 We adjusted for a range of important covariates and potential confounders: smoking status, alcohol consumption and the number of comorbid conditions (which include diabetes, hypertension, stroke, cardiovascular disease and anaemia). All covariates were treated as fixed at baseline. Analyses for hips and knees were performed separately, with prosthesis survival at the end of follow-up being of primary interest. Proportionality of hazards assumptions was assessed by examining complementary log-log plots of the cumulative incidence. As a sensitivity analysis we modelled the same data using standard methods which do not cater for competing risks (ie, Cox regression analysis with death as a censoring event). We also calculated stand-alone estimates for the cumulative incidence of revision surgery at 1, 5, 10 and 15 years, and plotted estimates of the age-specific, gender-specific and BMI-specific cumulative incidence curves for the whole cohort.

All tests of significance were at the 5% level and two-sided. Interval estimates were based on 95% CIs. The main statistical analysis was carried out using R (R Core Team, 2012. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and Stata (StataCorp. 2011; Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Participant demographics

Over the study period the database contained 63 162 patients undergoing THR and 54 276 patients undergoing TKR. The average age at replacement was similar in both the THR and the TKR groups but the proportion of women was greater for both THR and TKR (table 1). For those with a recorded preoperative BMI, the proportion of obese patients (BMI (≥30 kg/m2) was 26.2% for THR and 39.8% for TKR and the proportion of morbidly obese patients (which we define as having BMI (≥40 kg/m2) was 1.6% for THR and 3.6% for TKR. Eighty per cent of preoperative BMI values used were recorded within 5 years of the primary operation. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the cohort, including summary statistics and missing data percentages for all explanatory variables where complete data were not observed.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics—all participants undergoing total hip or knee replacement

| Total hip replacement (N=63 162) |

Total knee replacement (N=54 276) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (N=39 292) | Male (N=23 870) | Female (N=31 682) | Male (N=22 594) | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 70.5 (11.1) | 67.7 (11.0) | 70.7 (9.6) | 69.4 (9.4) |

| Gender (%) | 62.2 | 37.8 | 58.3 | 41.6 |

| BMI (mean, SD) | 27.2 (5.1) | 27.7 (4.3) | 29.6 (5.6) | 28.8 (4.4) |

| Missing BMI (%) | 19.1 | 19.3 | 13.8 | 14.0 |

| Revisions (N, %) | 1000 (2.55) | 811 (3.40) | 572 (1.8) | 614 (2.7) |

| Deaths prerevision (N, %) | 6615 (16.8) | 4201 (17.6) | 4110 (13.0) | 3349 (14.8) |

| Number of comorbid conditions (%) | ||||

| 0 | 42.8 | 48.1 | 37.5 | 43.7 |

| 1 | 34.2 | 31.0 | 37.4 | 35.8 |

| 2+ | 23.0 | 20.9 | 25.2 | 20.6 |

BMI, body mass index.

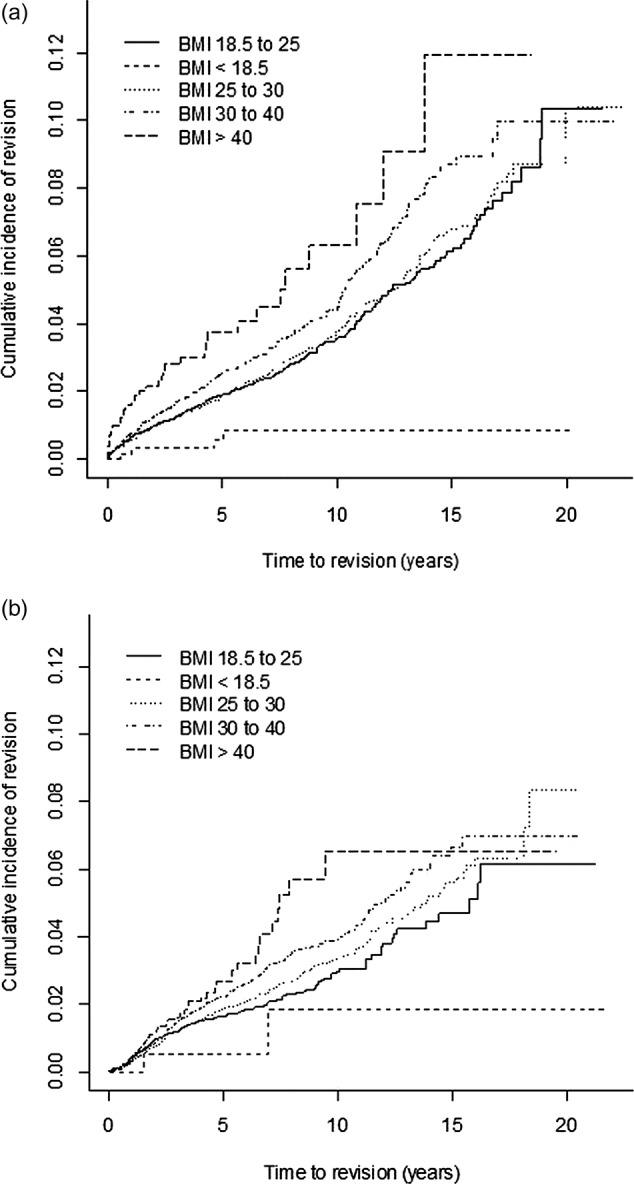

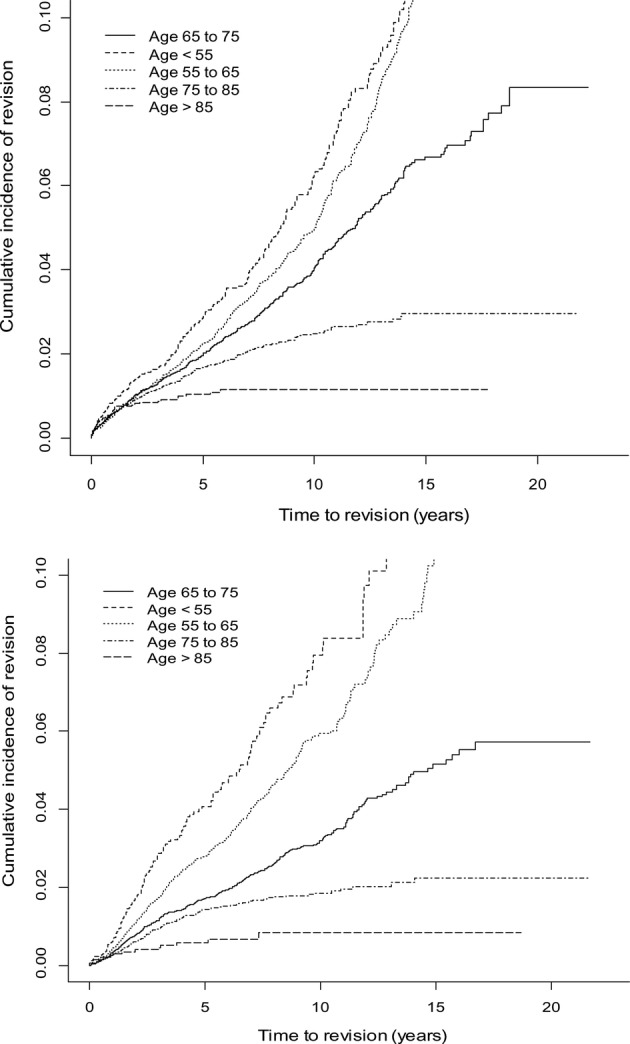

Survival analysis

The estimated cumulative incidence of revision at 5 years was 2% (95% CI 1.8% to 2.1%) for THR and 1.9% (95% CI 1.8% to 2.1%) for TKR. For women, cumulative incidence at 5 years was 1.8% (95% CI 1.7% to 2%) for THR and 1.6% (95% CI 1.5% to 1.8%) for TKR, and for men 2.2% (95% CI 2% to 2.4%) and 2.3% (95% CI 2.1% to 2.6%), respectively. Table 2 provides gender-specific estimates of cumulative incidence with point-wise CIs for a range of times (1, 3, 5, 10 and 15 years after THR/TKR). Figures 1 and 2 provide a further breakdown of the cumulative incidence of revision for the whole THR and TKR cohorts, respectively, with separate incidence curves for categorised BMI (figure 1) and categorised age (figure 2). Gray's test was used to examine whether there were differences in the overall cumulative incidence of revision by gender, categorised age (<55, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84 >85 years) and categorised BMI (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, 30–39.9 and >40 kg/m2). All three variables showed statistically significant differences in cumulative incidence for both hip (Gray's test statistic: gender, age, BMI, p<0.001 for all) and knee (Gray's test statistic: gender, age, BMI, p<0.001 for all).

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence rates for revision surgery at selected times following THR and TKR

| Hip |

Knee |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

|||||

| Years since total joint replacement | Cumulative incidence of revision (%) | 95% CI | Cumulative incidence of revision (%) | 95% CI | Cumulative incidence of revision (%) | 95% CI | Cumulative incidence of revision (%) | 95% CI |

| 1 | 0.6 | (0.5 to 0.6) | 0.7 | (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.3 | (0.2 to 0.4) | 0.4 | (0.3 to 0.5) |

| 3 | 1.2 | (1.1 to 1.3) | 1.4 | (1.3 to 1.6) | 1.1 | (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.5 | (1.4 to 1.7) |

| 5 | 1.8 | (1.7 to 2.0) | 2.2 | (2.0 to 2.4) | 1.6 | (1.5 to 1.8) | 2.3 | (2.1 to 2.6) |

| 10 | 3.4 | (3.1 to 3.6) | 4.6 | (4.3 to 5.0) | 2.8 | (2.5 to 3.1) | 4.5 | (4.1 to 4.9) |

| 15 | 6.0 | (5.5 to 6.6) | 8.3 | (7.6 to 9.1) | 4.4 | (3.9 to 5.0) | 7.1 | (6.2 to 8.1) |

THR, total hip replacement; TKR, total knee replacement.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence estimate for revision of (A) total hip replacement (B) total knee replacement by body mass index.

Figure 2 .

Cumulative incidence estimate for revision of (A) total hip replacement (B) total knee replacement by age.

In a single predictor (univariable) survival model allowing for the competing risk of death over the entire period of follow-up, we estimated that THR participants had a 3% increase in the subhazard of revision (SHR 1.030, 95% CI 1.020 to 1.041, p<0.001) for each extra unit (kg/m2) of BMI, with TKR participants showing a 2.6% increase per unit (SHR 1.026, 95% CI 1.013 to 1.038, p<0.001). The SHR was significantly greater for men compared with women for both THR (subhazard ratio (SHR)): 1.35, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.48, p<0.001) and TKR 2% (SHR 1.54, 95% CI 1.37% to 1.72%, p<0.001). Age at total joint replacement was also a significant univariable predictor of revision for both hip and knee, with THR participants estimated to have a 3% reduction in the SHR (0.970, 95% CI 0.967 to 0.973, p<0.001) for each extra year of age, with TKR participants showing a 4.3% reduction (SHR 0.957, 95% CI 0.952% to 0.961%, p<0.001).

The effects for all three variables (gender, age and BMI) were then estimated in multivariable competing risks regression models after adjusting for smoking status, drinking status and the number of comorbid conditions, again over the entire period of follow-up. For age, the estimates for the SHR were almost exactly the same as those from the univariable model for both hip and knee, but for gender (SHR 1.23 for hip; 1.51 for knee) and BMI (SHR 1.020 for hip; 1.015 for knee) the estimates were smaller. Nevertheless, all three variables remained statistically significant for both hip and knee in the presence of adjustment. For a 5-unit and 10-unit increase in BMI, this represents an increase in THR revision risk of 10.4% and 21.9%, respectively (7.7% and 16.1% for TKR).Testing for two-way interactions between age, gender and BMI did not produce any significant effects. All subhazard estimates (with 95% CIs and p values) from the univariable and multivariable models are given in tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Estimated subhazard of revision for total hip replacement—competing risks analysis

| Univariable |

Adjusted* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| BMI† (kg/m2) (per additional unit) | 1.030 | (1.020 to 1.041) | <0.001 | 1.020 | (1.009 to 1.032) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | (1.10 to 1.38) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 1.35 | (1.23 to 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.23 | ||

| Age (years at THR) (per additional year) | 0.970 | (0.967 to 0.973) | <0.001 | 0.971 | (0.966 to 0.975) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for smoking (yes/no/ex), drinking (yes/no/ex), number of comorbid conditions.

†BMI available in 86.1% of patients.

BMI, body mass index; THR, total hip replacement.

Table 4.

Estimated subhazard of revision for total knee replacement—competing risks analysis

| Univariable |

Adjusted* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| BMI† (kg/m2) (per additional unit) | 1.026 | (1.013 to 1.038) | <0.001 | 1.015 | (1.002 to 1.028) | 0.023 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | (1.32 to 1.73) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 1.54 | (1.37 to 1.72) | <0.001 | 1.51 | ||

| Age (years at THR) (per additional year) | 0.957 | (0.952 to 0.961) | <0.001 | 0.957 | (0.951 to 0.962) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for smoking (yes/no/ex), drinking (yes/no/ex), number of comorbid conditions.

†BMI available in 80.9% of patients.

BMI, body mass index; THR, total hip replacement.

To further explore the effect estimates for BMI we ran the same adjusted age-gender-BMI model described above, but used categorical BMI instead of continuous. For morbidly obese TKR participants (BMI 40+) there was a 43.9% increase (95% CI 2.6% to 103.9%, p=0.040) in the SHR compared with those with a normal BMI (18.5–25), but the effect for THR was larger (a 65.5% increase) and stronger (95% CI 15.4% to 137.3%, p=0.006). The effect sizes were similar to those obtained when using the adjusted sub-HR estimate of continuous BMI for a participant with a BMI of 45 relative to one with a BMI of 22 (increase of 57.7% for THR; 40.8% for TKR). For obese patients in the range 30–40 kg/m2 versus those with a normal BMI, the estimated sub-HR for revision was weakly significant for THR (15.7% increase, 95% CI 0.2% to 33.7%, p=0.048) but not for TKR (17.9% increase, 95% CI −1.9% to 41.6%, p=0.079).

As a sensitivity analysis, we also performed standard Cox regressions with revision surgery as the event of interest and where no distinction was made between death and other censoring events. Univariable models for age, gender and BMI gave very similar results to the competing risks analysis, as did the multivariable models which adjusted for the same factors as in the competing risks regression. Results from the Cox regression models are given in tables 5 and 6. In addition, we calculated that it would take 175 patients with TKR to reduce their baseline BMI from obese to normal in order to prevent one revision operation after 5 years. For patients with THR this number reduces to 152.

Table 5.

Estimated hazard of revision for THR—univariable and adjusted Cox regression analysis with death as a censoring event

| Univariable |

Adjusted* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| BMI† (kg/m2) (per additional unit) | 1.029 | (1.017 to 1.040) | <0.001 | 1.019 | (1.008 to 1.031) | 0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 1.36 | (1.24 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 1.26 | (1.13 to 1.41) | |

| Age (years at THR) (per additional year) | 0.978 | (0.974 to 0.983) | <0.001 | 0.977 | (0.972 to 0.982) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for smoking (yes/no/ex), drinking (yes/no/ex), number of comorbid conditions.

†BMI available in 86.1% of patients.

BMI, body mass index; THR, total hip replacement.

Table 6.

Estimated hazard of revision for TKR—univariable and adjusted Cox regression analysis with death as a censoring event

| Univariable |

Adjusted* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| BMI† (kg/m2) (per additional unit) | 1.024 | (1.012 to 1.037) | <0.001 | 1.015 | (1.003 to 1.028) | 0.019 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 1.58 | (1.41 to 1.77) | <0.001 | 1.55 | (1.36 to 1.77) | |

| Age (years at THR) (per additional year) | 0.962 | (0.956 to 0.967) | <0.001 | 0.961 | (0.955 to 0.968) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for smoking (yes/no/ex), drinking (yes/no/ex), number of comorbid conditions.

†BMI available in 80.9% of patients.

BMI, body mass index; THR, total hip replacement; TKR, total knee replacement.

Finally, we assessed whether the higher incidence of hip revision surgery during the first year following THR (see figures 1A and 2A) might compromise the proportionality assumption and therefore suggest the inclusion of time-dependent effects. Separate univariable piecewise competing risk models for hip revision were fitted for gender, age (≤65 years vs >65) and BMI (>40 vs ≤40). A single change point at 1 year was used to simultaneously estimate two sub-HRs for revision (before and after 1 year following THR). The only model which provided some evidence for a different sub-HR during the first year was with BMI (>40 vs ≤40) as the predictor (SHR 2.619, 95% CI 1.502 to 4.560, p=0.001), but this was not matched with a statistically significant estimate for revision after the first year (SHR 0.575, 95% CI 0.238 to 1.170, p=0.130).

Discussion

This study presents population-based estimates for the risk of revision following total joint replacement of the hip and knee using methods from survival analysis. Cumulative incidence rates of revision were higher for men than for women and higher for hips than knees. Age, gender and BMI were estimated to be significant predictors of time to revision in an adjusted model allowing for the competing risk of death. Severely obese patients undergoing THR were observed to have a higher risk of revision surgery during the first year following replacement, but the same effect was not observed for knee replacement.

The literature on obesity as a risk factor for hip and knee arthroplasty concentrates mainly on the risk for primary replacement rather than for revision procedures, and most use rate differences to estimate relative risk, rather than using time-to-event methods. Many published studies are small and do not have sufficient power to detect rare outcomes. Often these studies are locally based and the generalisability to population level is questionable. Mostly results are presented for categorised BMI, which is often dichotomised at 30 kg/m2, and where results for the morbidly obese are reported, the sample size is small.

One of the largest studies examining primary replacement followed up a cohort of over 490 000 middle-aged women over an average of 2.9 years and found increased incidence of hip and knee replacement in obese participants.18 Of the studies which consider the effect of obesity on outcomes after primary joint replacement, several focus mainly on events such as complications arising from surgery19 or subsequent admission to an intensive care unit,20 rather than the time to revision surgery. Among studies of other non-revision outcomes, Andrew et al21 looked at the change in Oxford Hip Score 5 years after THR and found no difference between non-obese, obese and morbidly obese patients, but in a smaller study22 using Harris Hip Score (HHS) with the same length of follow-up, an increase in BMI was associated with a small but significant reduction in HHS.

An editorial on obesity and joint replacement in 200623 suggested that it is those with BMI of greater than 40 units (rather than 30) who are at risk of worse outcomes, yet several subsequent studies have used a BMI cut-point of 30 kg/m2. A recent Australian study of 2026 patients with THR and 535 with TKR found no difference in mid-term survival rates between the obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) and non-obese.24 Another study from Switzerland used Cox regression to estimate the risk of revision in 2495 THRs using the same cut-point for BMI, estimating a non-significant adjusted HR for revision of 2.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 5.3) for obese versus non-obese patients.19 However, a recent Canadian study of 3290 THRs did categorise BMI to include a morbidly obese group (BMI>40 kg/m2) and although the authors found no difference in time to revision between BMI categories in an unadjusted analysis, there was a marginally significant difference for septic revisions.25

Our results suggest that there may be a 1.5–2% rise in the risk of knee and hip revision, respectively, for each extra unit of BMI. However, there is some variation in risk across the entire range of observed BMI values. For hips, there appears to be very little difference in BMI-related risk between the normal weight and overweight categories. However, figure 1A shows that for hips there may be a revision rate of approximately 6% for the morbidly obese after 10 years, against a 3% rate for the normal and overweight. For knees, figure 1B shows a more even distribution across the BMI categories up to about 7 years after TKR, but with higher risk for the morbidly obese between 7 and 10 years after TKR.

Although recommendations26 27 to consider the use of the cumulative incidence function for analysing prosthesis survival are gaining acceptance,28 the use of competing risks regression to model associated risk factors is still not widely observed. The justification for using competing risks methods in our primary analysis is that hip and knee prostheses are mainly implanted in older patients for whom mortality is a substantial competing risk which may be several times greater than the risk of revision. What is perhaps surprising is that our results show little difference between the HR and sub-HR estimates from the Cox and the competing risks regression models, respectively, although the former has a cause-specific interpretation with no distinction between death and censoring whereas the latter directly models the cumulative incidence of revision.

Strengths and potential limitations of the study

The strengths of the study data more than the make up for its limitations. GPRD data have individual date-stamped records of patient event data in primary and secondary care settings, including data on many potential confounders, including comorbidities, BMI, smoking and drinking. The GPRD practice network covers all of the UK, and approximately 5% of all practices are covered by the GPRD. The high degree of generalisability afforded by this very large sample enables population-level inferences to be made. Follow-up is long, with several hundred prostheses in the dataset having over 20 years of follow-up without being revised. The choice of the statistical methods used to allow for the competing risk of death adds a further degree of robustness to the study. The regression estimates of the HR for BMI as a factor associated with revision benefit from a precision which is not usually achievable outside of national registers, especially for the group of morbidly obese patients within which event rates in the literature are low.

There are several limitations to this work. The revision rate estimates hip and knee at 5 years are close to, but slightly less than those reported by the NJR, but the GPRD data used in this study include prostheses implanted from the late 1980s. Also our data do not have directly linked information on the indication for surgery, which would have been enabled a subanalysis by reason for revision. Although certain indications for revision are more common than others depending on follow-up time (eg, infection occurring early), any inferences about indication-specific risks before or after a given follow-up time would not have been reliable.

Conclusion

This study has presented estimates of rates and risk factors for revision surgery on hip and knee prostheses using one of the largest available population-based sets of joint replacement data outside of national arthroplasty registries. Our estimates suggest that BMI is positively associated with the risk of hip and knee revision, but studies of register data linked with sources of demographic and clinical data are needed in order to distinguish between effects for specific indications for revision surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the general practitioners and their patients who have consented to give information to the GPRD along with the MRC support in providing access to the database.

Footnotes

Collaborators : The following people are members of the COAST Study group: Cyrus Cooper, Mark Mullee, James Raftery, Andrew Carr, Andrew Price, Kassim Javaid, David Beard, Douglas Altman, Nicholas Clarke, Jeremy Latham, Sion Glyn-Jones and David Barrett.

Contributors: All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. NKA had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. DC, AJ and NKA participated in study conception and design. NKA participated in acquisition of the data. DC, JM, AJ and NKA participated in analysis and interpretation of the data.

Funding: This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0407–10064). The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Support was also received from the Oxford NIHR Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit, Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, University of Oxford and the UK Medical Research Council, Medical Research Council Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southampton.

Competing interests: NKA has received consultancy payments, honoraria and consortium research grants, respectively, from: Flexion (PharmaNet), Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Q-Med, Roche; Amgen, GSK, NiCox and Smith & Nephew; Novartis, Pfizer, Schering-Plough and Servier.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Cyrus Cooper, Mark Mullee, James Raftery, Andrew Carr, Andrew Price, Kassim Javaid, David Beard, Douglas Altman, Nicholas Clarke, Jeremy Latham, Sion Glyn-Jones, and David Barrett

References

- 1.2012. National Joint Registry for England and Wales: 9th Annual report.

- 2.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, et al. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone J Surg Am 2005;87:1487–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturmer T, Dreinhofer K, Grober-Gratz D, et al. Differences in the views of orthopaedic surgeons and referring practitioners on the determinants of outcome after total hip replacement. J Bone J Surg Br 2005;87:1416–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santaguida PL, Hawker GA, Hudak PL, et al. Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Can J Surg 2008;51:428–36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2011. Commissioning Policy Statement: Referral and surgical threshold criteria for elective primary Hip Replacement Surgery.

- 6.2011. Clinical threshold: hip replacement for the treatment of joint symptoms and functional limitation.

- 7.Commissioning decision: Hip and knee replacement surgery in obese patients (those with a body mass index of 30 or greater) Peninsula Commissioning Priorities Group, 2011

- 8.Maradit Kremers H, Visscher SL, Moriarty JP, et al. Determinants of direct medical costs in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:206–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanhegan IS, Malik AK, Jayakumar P, et al. A financial analysis of revision hip arthroplasty: the economic burden in relation to the national tariff. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:619–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Society of Arthroplasty Registers. http://www.isarhome.org/directory.

- 11.Serra-Sutton V, Allepuz A, Espallargues M, et al. Arthroplasty registers: a review of international experiences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2009;25:63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, et al. International survey of primary and revision total knee replacement. Int Orthop 2011;35:1783–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jameson SS, Baker PN, Mason J, et al. Independent predictors of revision following metal-on-metal hip resurfacing: a retrospective cohort study using National Joint Registry data. J Bone J Surg Br 2012;94:746–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havelin LI, Robertsson O, Fenstad AM, et al. A Scandinavian experience of register collaboration: the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA). J Bone J Surg Am 2011;93(Suppl 3):13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkinson J, Davis S. TP vs the general practice research (GPRD) database: now and the future. In: Mann R, Andrews E, eds. Pharmacovigilance. 2nd edn Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2007:341–8 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, et al. Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:783–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B, Balkwill A, Banks E, et al. Relationship of height, weight and body mass index to the risk of hip and knee replacements in middle-aged women. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:861–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubbeke A, Stern R, Garavaglia G, et al. Differences in outcomes of obese women and men undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:327–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AbdelSalam H, Restrepo C, Tarity TD, et al. Predictors of intensive care unit admission after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012;27:720–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrew JG, Palan J, Kurup HV, et al. Obesity in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:424–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubbeke A, Katz JN, Perneger TV, et al. Primary and revision hip arthroplasty: 5-year outcomes and influence of age and comorbidity. J Rheum 2007;34:394–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horan F. Obesity and joint replacement. J Bone J Surg Br 2006;88:1269–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeung E, Jackson M, Sexton S, et al. The effect of obesity on the outcome of hip and knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2011;35:929–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCalden RW, Charron KD, MacDonald SJ, et al. Does morbid obesity affect the outcome of total hip replacement?: an analysis of 3290 THRs. J Bone J Surg Br 2011;93:321–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fennema P, Lubsen J. Survival analysis in total joint replacement: an alternative method of accounting for the presence of competing risk. J Bone J Surg Br 2010;92:701–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, et al. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. II. Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011;82:258–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillam MH, Ryan P, Graves SE, et al. Competing risks survival analysis applied to data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Acta Orthop 2010;81:548–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.