Abstract

Like cellular proteins that form fibrillar nanostructures, small hydrogelator molecules self-assemble in water to generate molecular nanofibers. In contrast to the well-defined (dys)functions of endogenous protein filaments, the fate of intracellular assembly of small molecules remains largely unknown. Here we demonstrate the imaging of enzyme-triggered self-assembly of non-fluorescent small molecules by doping the molecular assemblies with a fluorescent hydrogelator. The cell fractionation experiments, fluorescent imaging, and electron microscopy indicate that the hydrogelators self-assemble and localize to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are likely processed via the cellular secretory pathway (i.e., ER-Golgi-lysosomes/secretion). This work, as the first example of the use of correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM) for probing the selfassembly of non-fluorescent small molecules inside live mammalian cells, not only establishes a general strategy to provide the spatiotemporal profile of the assemblies of small molecules inside cells, but may lead to a new paradigm for regulating cellular functions based on the interactions between the assemblies of small molecules (e.g., molecular nanofibers) and subcellular organelles.

Keywords: self-assembly, small molecule, nanofibers, intracellular, localization, enzyme

Introduction

Self-assembly of biomacromolecules into fibrillar nanostructures is a fundamental process in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. While the cytoskeletal filaments (e.g., F-actin, lamin, or microtubules) are essential for cell mechanics,1 the self-assembly of aberrant proteins into nanofibers is closely associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Pick’s, Parkinson’s or Huntington’s disease.2 Due to their importance in cell biology, intracellular protein filaments (normal and abnormal) have attracted intensive research activities on many levels (organismic to molecular). These researches have provided valuable insights, such as the identification of an array of cytoskeleton-regulatory proteins that are responsible for actin-based cellular phenomena,3 the elucidation of the non-covalent bonds for interconnecting the fibers in intermediate filaments,4 and the intracellular protein-degradation pathway for removing abnormal protein filaments.5 These advances not only contribute significantly to the understanding of the molecular mechanism of intracellular protein filament formation and function, but lay the foundation for the study of intracellular nanofibers self-assembled or polymerized from exogenous molecules, which is scientifically intriguing and potentially significant, but has barely been explored.6, 7

Small molecular hydrogelators8, 9 that self-assemble in water to form molecular nanofibers8, 10 share the common features, such as amphiphilicity and the formation of non-covalent bonds (e.g., hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic forces), with the proteins that form the intracellular filaments. Besides being driven by non-covalent bonds to form ordered filamentous assemblies, several features of the hydrogelators make them an attractive system for exploring the properties of molecular nanofibers in cells. First, non-covalent bonds between the hydrogelator molecules promote the interactions among the molecular nanofibers, resulting in their entanglement and the entrapment of water in the nanoscale interstices, a process that is called supramolecular hydrogelation.8 The macroscopic changes of hydrogelation, i.e., the stop of liquid flow, can be easily detected by eye, and thus the formation of a hydrogel serves as a simple assay for rapid screening of a small molecule as a hydrogelator for forming molecular nanofibers. Second, because of their small size, hydrogelators (or their precursors) easily enter cells via passive diffusion,11 which makes it possible to use the cell machinery and fundamental biological processes (e.g., enzyme catalysis) to regulate intracellular selfassembly and the formation of molecular nanofibers. Third, the molecular nanofibers of hydrogelators may exhibit unexpected bioactivities. For example, the self-assembling small molecules to form molecular nanofibers that promote activation of procaspase-3,12 disrupt the elongation of microtubules,13 and serve as a mimic of cytoskeleton in a model protocell.14

Our previous study has demonstrated a successful strategy to image real-time molecular self-assembly inside live cells, which occurs in a short time (<1 hr) on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) because the process is dominantly initiated by PTP 1B with high activity on the cytoplasmic face of ER. Furthermore, we are able to identify that the micro-morphology of these intracellular molecular assemblies are nanofibers after cell fractionation.15 Nevertheless, there is a major limitation on the requirement of fluorescence labeling. Actually, fluorescence labeling is the most common technique in the biological analysis16–18 but has been found to raise certain undesired issues, e.g. toxicity,19 alteration of macromolecular interactions.20 Consequently, it usually requires an extensive study to confirm the innocence of the attached fluorophores21 or turns to the label-free imaging technique based on the vibration spectrum of target molecule which requires specialized equipment.22 However, it remains unknown whether the supra-molecular self-assembly will induce notable molecular vibration shift for the stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy to distinguish molecular aggregates from their monomers.

Hence, in this work we manage to image the self-assembly of small molecules without fluorescence labeling (native form) inside mammalian cells with a doping method23, 24 after a longer incubation time (2 days). That is, by incorporating dansyl (DNS) labeled molecule into the self-assembly of the native molecules, we are able to determine the formation, localization, and progression of molecular assemblies generated from the nonfluorescent small molecular hydrogelators8, 25 by an enzyme-triggered hydrogelation mechanism25–29 inside live mammalian cells. We confirmed that, upon enzyme catalysis, the precursors of the hydrogelators turn into the corresponding hydrogelators and self-assemble into molecular assemblies. We demonstrated that (i) the precursors passively diffuse inside cells; (ii) the molecular assemblies occur on ER because the cell fraction containing ER triggers the most rapid sol-gel transformation in vitro; and (iii) correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM)30 further indicates that the molecular assemblies localize near or inside the ER and are likely processed via the cellular secretory pathway (e.g., ER-Golgi-lysosomes/secretion31) by cells, albeit less efficiently. This work not only establishes a general strategy to provide the spatiotemporal profile of molecular assemblies inside cells, but indicates that molecular assemblies of small molecules may provide a new model system to mimic and to understand the cellular mechanisms and processes related to endogenous-normal and aberrant-protein nanofibers.

Results and Discussions

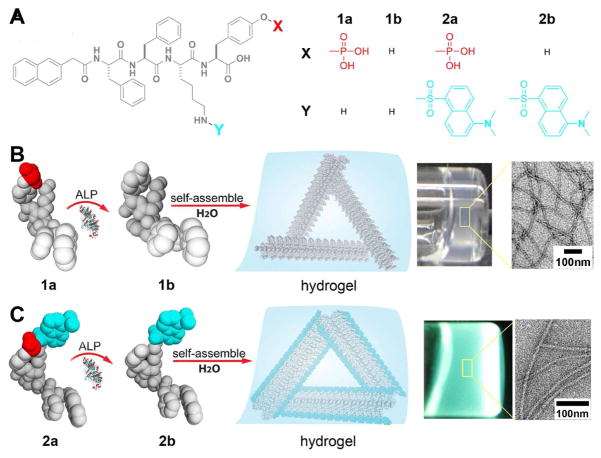

Figure 1A shows the structures of the non-fluorescent precursor (1a) and its fluorescent analog (2a) with a DNS labeling, as well as the corresponding dephosphorylated products (1b, 2b) catalyzed by a cellular phosphatase (ALP). Critical components of these molecules are a self-assembly motif32 and an enzyme-cleavable group (here the phosphate ester on a tyrosine residue). Upon catalytic dephosphorylation by an alkaline phosphatase, 1a converts to hydrogelator 1b, which self-assembles in water to form molecular assemblies (11±2 nm in diameters), starting at the critical concentration of 235 μM (0.18 mg/mL) (Fig. S1). At a 10-times higher concentration, molecular assemblies of hydrogelator 1b entangle and generate self-supported hydrogels (Fig. 1B) 33.

Figure 1.

(A) The molecular structures of precursors 1a, 2a, and their corresponding hydrogelators 1b, 2b, respectively. (B and C) Illustrations showing the basic steps of enzyme-instructed self-assembly and formation of molecular assemblies and hydrogels: the precursor molecules 1a (B) and 2a (C) are converted to hydrogelators 1b (B) and 2b (C) by dephosphorylation catalyzed by alkaline phosphatase (ALP); these hydrogelators self-assemble in water to form molecular assemblies that generate hydrogels. Towards the right, optical images of hydrogels of the small molecules 1b (B) and 2b (C) (ALP catalyzed conversion of 1a (0.2 wt%, 2.35 mM) (B), ALP catalyzed conversion of 2a (0.6 wt%, 5.5 mM) (C)). The zoom-in transmission electron microscope (TEM) image on the very right show the detailed structure of negatively stained molecular assemblies of 1b (B) and 2b (C).

In a recent in vitro study we already demonstrated the hydrogelation and the formation of molecular assemblies by self-assembly of the small molecule 1b in water.33 However, here we explore the behavior of this hydrogelator in cellular environment, which is highly crowded with a variety of cellular organelles and a large amount of biomacromolecules. This high degree of complexity presents a challenge for the direct observation of the molecular assemblies in living cells.34 While 1a conjugated with different fluorophores has shown drastically distinguishable spatiotemporal distribution of molecular aggregates within cellular environment, the fluorophore labeled molecules still differ from the native molecules. Because fluorescent microscopy is a highly sensitive technique, we choose to dope a small amount of fluorescent 2b into the nanofibers of 1b, which will allow the visualization of the assemblies of 1b under fluorescent microscope.

As shown in Figure 1C, being treated with the alkaline phosphatase, the precursor 2a (5.5 mM or 6 mg/mL) transforms into the hydrogelator 2b, which also self-assembles in water to generate a transparent, fluorescent hydrogel within 2 hours. Similar to the enzymatically formed molecular assemblies of 1b, the molecular assemblies of 2b are 11±2 nm in diameter and several microns in length (Fig. 1B and C). Their structural similarity allows hydrogelators 1b and 2b to co-assemble into the same molecular assemblies (Fig. S2). This property is useful for cell imaging, because the ratio between the two components can be tuned to optimize fluorescence imaging conditions.

To study whether the non-fluorescent precursor molecules enter and remain in living cells and then transform into mature hydrogelators, we incubated HeLa cells with 500 μM of 1a for 2 days, washed extracellular precursors away, lysed the cells and then determined the concentration of 1a and 1b by LC-MS (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3 A–B). We found that the average concentration of 1b inside HeLa cell is 0.26–0.94 mg/mL (0.34–1.23 mM), which is above the critical concentration of forming molecular assemblies formation determined by in vitro tests. This result establishes both that intracellular phosphatases convert 1a to 1b, and that the intracellular accumulation of 1b is sufficiently high to drive intracellular the formation of molecular assemblies that may result in hydrogelation inside HeLa cells.

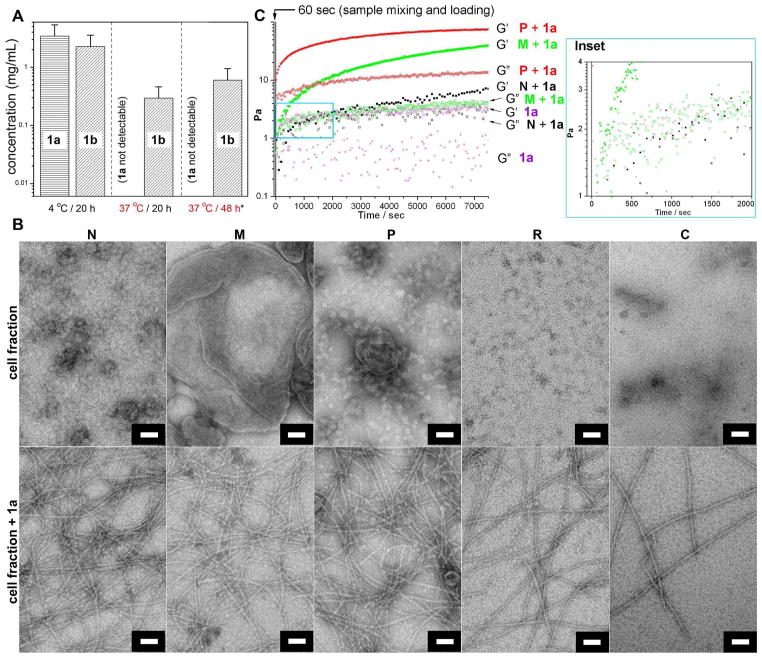

Figure 2.

(A) The average intracellular concentrations of precursor 1a and hydrogelator 1b were determined by LC-MS after incubating HeLa cells with precursor 1a at concentration of 500 μM and temperatures of 4 °C or 37 °C up to two days (*These cells were co-incubated with additional 2a at the concentration of 200 nM). (B) Typical TEM images showing the morphology of each cell fraction itself and with the addition of 1a at the concentration of 6 mg/mL after 24h (for N, M, and P) and 48h (for R and C). Scale bar: 500 nm for cell fraction N and 50 nm for the rest. (C) The storage/loss modulus measurement at a time mode by oscillatory rheometry showing the gelation points of the mixture of each cell fraction with 1a at the concentration of 6 mg/mL; (Inset) Enlarged area boxed by the blue lines in (C).

We also incubated the HeLa cells with 1a (500 μM) at 4 °C or 37 °C for 20 hours and determined the concentration of 1a and 1b inside the cells (Table S1). As the result shown in Figure 2A, at 4 °C, the concentrations of 1a and 1b are 1.49–5.37 mg/mL (1.75–6.29 mM) and 0.99–3.55 mg/mL (1.28–4.57 mM), respectively. In addition, 1b forms the hydrogel at 1.8 mg/mL (2.35 mM) even if it is generated enzymatically at 4 °C (Fig. S3 C). At 37 °C, the concentration of 1b is 0.13–0.46 mg/mL (0.17–0.60 mM), while 1a is undetectable, similar to the 48 hour incubation at the same temperature. These results have three major implications: first, the presence of 1a in addition to 1b inside cells incubated at 4 °C suggests that the precursor of 1a enters cells via energy independent processes, such as passive diffusion,35 but then its intracellular conversion to mature hydrogelator 1b and self-assembly to molecular assemblies is incomplete, likely due to greatly reduced enzyme activity at 4 °C. In contrast, at 37 °C virtually all intracellular 1a has been converted into 1b after both 20 and 48 hours. Second, despite of the slower 1a-to-1b conversion and the rate of selfassembly inside the cells incubated at 4 °C, the total concentration of 1b at 37 °C is considerably lower than at 4 °C. Together with the observation of 1b in lysosomes and Golgi (vide infra), this result suggests that the cells actively reduce the presence of intracellular molecular assemblies in a process that is slowed at low temperatures. Third, there is more 1b inside the cells after 48 h of incubation than 20 h of incubation at 37 °C, confirming the accumulation of 1b over time and implying an inefficient removal of the nanofibers by the cells.

Our results show that the precursor molecules can passively diffuse through the membranes, which should also allow them to enter the membrane-enclosed organelles. To determine the distribution of phosphatases in different cell compartments and to infer the possible cellular location of the enzymatic dephosphorylation of 1a and hydrogelation, we fractioned the cell components using differential centrifugation.36 After lysing HeLa cells by differential centrifugation, we obtained five cell fractions: N (nuclei), M (mitochondria, lysosomes, and peroxisomes), P (plasma membrane, microsomal fraction (= fragments of endoplasmic reticulum, golgi and other vesicles) and large polyribsomes), R (ribosomal subunits and small polyribosomes), and C (cytosol). After fractionation, 100 μL of each fraction is mixed with 200 μL of 1a (final concentration in the mixture is 6 mg/mL) for estimating the time required for hydrogelation by visual inspection. Fraction P induces hydrogelation faster (< 2 hours) than fraction N or M does (overnight), while fractions R and C fails to convert the mixture into a self-supported hydrogel.15 Negative-staining EM37 of the cell fractions alone (Fig. 2B, top row) and after 24 hour incubation with 1a (Fig. 2B, bottom row) confirms the presence of molecular assemblies of 1b only in latter samples. Although the molecular assemblies in the samples with hydrogelator exhibit identical morphologies (i.e., widths of 10±2 nm), the density and crosslink of the molecular assemblies is considerably higher in the cell fractions P, N, and M than in R and C (Fig. 2B). Although we observed cell fractions to cause the molecular self-assembly previously, here we use the rheometry to determine the gelation point more precisely for the comparison of the capability of triggering hydrogelation by each cell fraction. The storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″ measured in rheological tests confirm that the crosslinking and the density of molecular assemblies are higher inside the samples treated with P, N and M fractions than those treated with R and C (Fig. S4). To quantify the rate of formation of the molecular assemblies, we used oscillating rheometry to measure the gelation point, i.e., the time point when G′ dominates G″,38 for 1a mixed with the cell fractions of N, M and P. As shown in Figure 2C, the gelation points for the mixtures are less than 60 s for fraction P (which is within the sample mixing and loading time), 1560 s for N and 260 s for M. The highest rate of formation of molecular assemblies and hydrogelation in the sample with cell fraction P indicates that a large amount of intracellular molecular assemblies should associate with the cellular components of the P fraction. We also examined the cell fractions by TEM after incubating the HeLa cells with the precursor (1a). We found the cell fractions M and P containing the nanofibers (with the width of 10±2 nm), which are absent in the fractions M and P of untreated HeLa cells (Fig. S5). This result supports the formation of molecular assemblies inside the cells. The appearance of the nanofibers in fraction M likely arises from the high molecular weight of the nanofibers network to allow them to be more sedimentable.

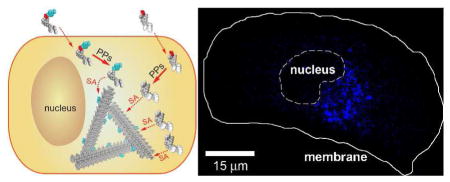

For the study of the localization of molecular assemblies inside HeLa cells by fluorescent microscope, we incubated the HeLa cells with a mixture of the fluorescent precursor 2a, at low enough concentration concerning imaging quality (photon saturation issue) and cytotoxicity, and the non-fluorescent precursor 1a, at high enough concentration to induce self-assembly for generating 1b/2b-molecular assemblies. Hydrogelators 1b and 2b share the same self-assembly motif, which allows the mixture of 1b and 2b to form the molecular assemblies at the critical concentration of 1b (235 μM, Fig. S1). This method provides a simple way to permit using fluorescence imaging to determine subcellular localization of the molecular assemblies inside cells (Fig. 3).

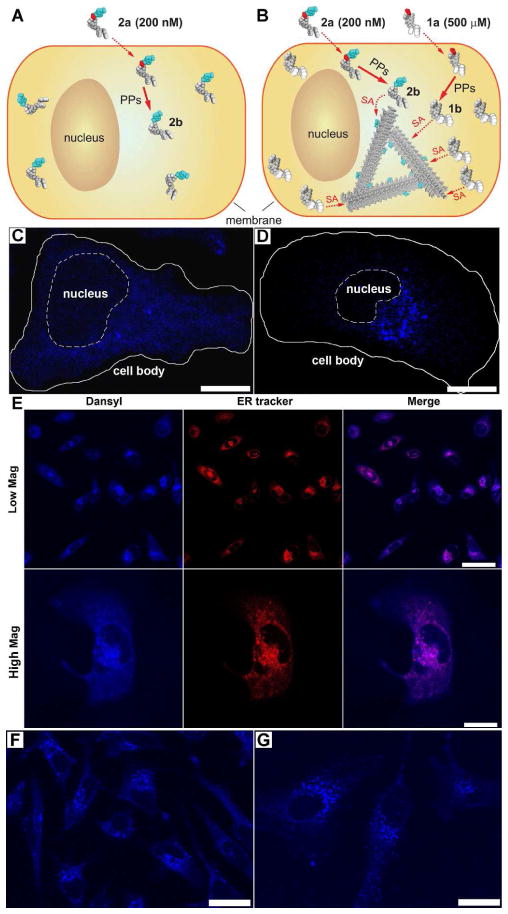

Figure 3.

(A–D) are illustrations (A, B) and fluorescence images (C, D) of two experiments that use a precursor mixture of 1a+2a (B, D) or only 2a (A, C). HeLa cells incubated with precursor 2a alone at 200 nM, which allows fluorescence imaging, but is lower than the critical concentration for filament self-assembly, show weak diffuse fluorescence throughout the cytosol (C), indicating the lack of formation of the formation of the molecular assemblies (A). Incubating HeLa cells with a precursor mixture of 200 nM of 2a and 500 μM of 1a results in intensified fluorescence localized to spots close to the nucleus (D), indicating the formation of 1b/2b-molecular assemblies (B). Scale bars: 15 μm. (SA = self-assembly, PP = protein phosphatase). (E) Confocal images of HeLa cells incubated with the same condition as shown in Fig. 3B and stained either with ERTracker™. Scale bars: 50 μm (top row); 20 μm (bottom row). Confocal images of the HeLa cells incubated by (F) Sequence I or (G) Sequence II (see text for details). Scale bars: 25 μm.

After incubating the HeLa cells with precursor 2a alone at a sub-critical concentration (200 nM) for 48 h or above the critical concentration with 1a (500 μM) and 2a (200 nM) together, the cells were washed by an additional incubation (24 h) in precursor-free culture medium to remove any extracellular 2a and to reduce the background. Confocal imaging of these HeLa cells (Fig. 3C and D, Fig. S6 A–B) reveals several features: (i) the nucleus and the cell surface show little fluorescence (further confirmed in Fig. S7 A), suggesting that the fluorescent molecules (2a, 2b, and 1b/2b-molecular assemblies) neither attach to the cell surface nor enter the nucleus. (ii) At sub-critical concentration of the precursor 2a (200 nM), 2b distributes almost uniformly in the cytosol (Fig. 3C), indicating little specific binding between individual molecules of 2b and specific cellular organelles. (iii) Above the critical concentration of 1a (500 μM) mixed with 2a (200 nM), the fluorescence is more concentrated, especially in spots that localize near the nucleus, suggesting that the 1b/2b molecular assemblies localize at the region of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (further confirmed in Fig. 3E) and/or Golgi.

We used an ER-Tracker™ Red-dye to stain the cells after the above described incubation with 1a and 2a to confirm that colocalization of the 1b/2b-molecular assemblie with the ER region. Figure 3E shows that the blue fluorescence from the dansyl group overlaps completely with the red fluorescence from the ER tracker, confirming that the molecular assemblies made of 1b and 2b localize to the ER. In contrast, there is little overlap between the signal 1b/2b-molecular assemblies and the orange fluorescence of the nucleic acid stain, SYTO® 85 (Fig. S7 A), confirming that the molecular assemblies unlikely localize in the nuclei or mitochondria. We also used Golgi tracker (BODIPY® TR C5-ceramide complexed to BSA) and LysoTracker® Red DND-99 to stain Golgi and lysosomes and found that the fluorescence of molecular assemblies partially overlaps with both organelles (Fig. S7 B–C), suggesting that cells likely process the molecular assemblies via the secretion pathway (ER-Golgi-lysosomes/secretion).

To confirm both that 1b and 2b co-assemble into 1b/2b-molecular assemblies and that 2b integrates into preassembled 1b-molecular assemblies inside the cells, we changed the order of the addition of 1a and 2a to the HeLa cells. Sequence I is to add 2a (200 nM) at day 1, wash with the buffer solution at day 2, and add 1a (500 μM) at day 3; in contrast, sequence II is to add 1a (500 μM) at day 1, 2a (200 nM) at day 2, and wash with the buffer at day 3. As shown in Figure 3, the localization of 2b to the ER region occurs with both sequence I (Fig. 3F) and sequence II (Fig. 3G). Both experiments result in similar images to that shown in Figure 3D, indicating that the intracellular molecular assemblies recruit other small molecules with the same self-assembly motif for the integration into the nanofibers. Additionally, the cell viability assays indicate little cytotoxicity of 1a and 2a at the concentrations lower than 500 μM33 and 200 μM (data not shown here), respectively. Therefore, the localization of the molecular assemblies is unlikely a result of the cells undergoing cell death.

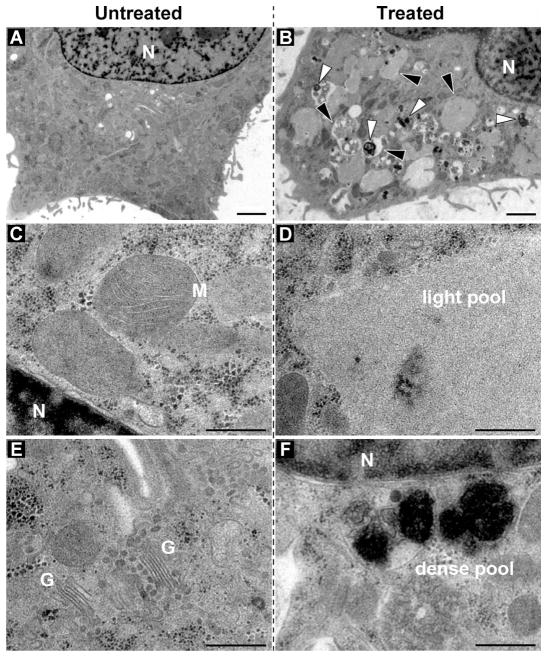

We also used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of high-pressure frozen/freeze-substituted HeLa cells to study the effects of the molecular assemblies on the cellular ultrastructure. The structural comparison of the untreated HeLa cells (as the control, Fig. 4A) with the HeLa cells treated with 500 μM precursor 1a reveals several modifications and a few new structural features (Fig. 4B). At a higher magnification, Figure 4D and 4F show two types of membrane-bound compartments: the large pools of the materials with low electron-density and the smaller vesicles with highly electron-dense substances. While the light compartments could be the large vesicles derived from the ER that include the accumulated hydrogelators, the darker granules could be the lysosomes with the molecular assemblies that appear to undergo degradation (evidenced by the observation of the fragment of 1a in LC-MS analysis (Fig. S3 A–B). This result suggests that the HeLa cells likely treat the molecular assemblies of 1a as the proteins targeted for degradation. To verify if the membrane-bound compartments associate with autophagy, we incubated the HeLa cells with 1a and rapamycin, an antibiotic that induces autophagy to reduce the toxicity of abberant proteins.39 We found that rapamycin hardly decreased the cytotoxicity of 1a, which suggested that the degradation of 1a or 1b via autophagy is unlikely.

Figure 4.

TEM images of the high-pressure frozen/freeze-substituted and plastic sectioned HeLa cells that were either untreated (A) or incubated with 500 μM of precursor 1a (B). (C–F) the same as in (the top row), but the ultrastructure is shown at higher magnification. Note the pools of low electron dense (black arrowheads) and electron dense material (white arrowheads) in the treated cells. N, nucleus; M, mitochondria; G, golgi stack. Scale bars: 2 μm (top), 500 nm (C–F).

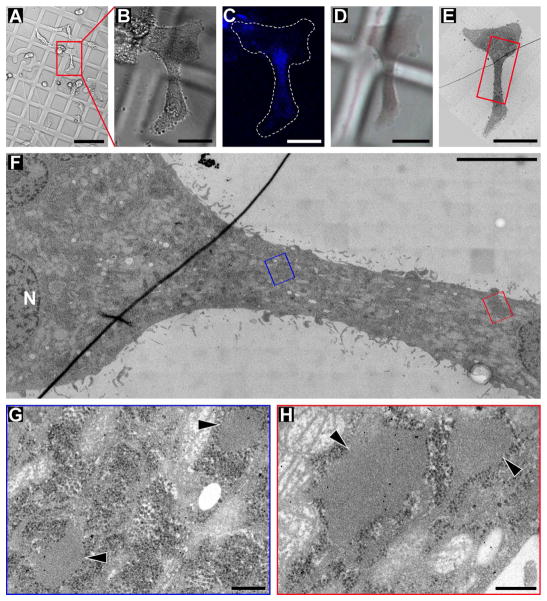

To demonstrate that the observed ultrastructural changes of the treated cells (Fig. 4) are directly connected to the self-assembly of the molecular assemblies of 1b, we used correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM) to image the HeLa cells treated with 1a and 2a. This allows us to correlate the fluorescence signal of 1b/2bmolecular assemblies imaged in live cells just before their rapid freezing for the EM sample preparation. The ultrastructural organization of the same cells was imaged by TEM (Fig. 5). CLEM reveals a high accumulation of vesicles with low electron-dense material in the cytoplasmic region that also shows high fluorescence signal. Moreover, the CLEM experiment on a health cell (which adheres and spreads on the grid) establishes the direct correlation between the fluorescent region and the features observed in TEM, which excludes the possibility that the features in TEM arise from cellular stresses that would affect the entire lumen. Although the filamentous assemblies and the bundles are observed in the cytoplasm of the treated (and untreated) HeLa cells, the resolution of plastic section TEM is not sufficient to unambiguously distinguish molecular assemblies from endogenous cytoskeletal intermediate or actin filaments. The molecular assembly-specific electron-dense labels are not available. Therefore further studies are required for a detailed description of the micro-morphology of intracellular molecular assemblies, to verify whether the low electron density material in the vesicles is a hydrogel-forming network of molecular nanofibers (Fig. S8 A). A modified method for EM sample preparation may be desired since the solvent displacement during EM sample preparation here could somehow blur the nanostructure of molecular assemblies, which makes the fine structure indistinguishable (Fig. S8 B).

Figure 5.

Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM) of HeLa cells incubated for 48 h with 500 μM of 1a and 200 nM of 2a. (A–C) DIC and fluorescence light microscopy images of treated HeLa cells growing on Aclar plastic film; the low magnification DIC overview (A), the zoom-in DIC image (B) of one cell of interest (red box in A) and the zoom-in fluorescence image (B) of the same cell were recorded only a few minutes before the sample was high-pressure frozen; note that the Aclar film was marked with a pattern for tracking cells of interest throughout the CLEM sample preparation. In (C) note the highest intensity of fluorescence signal in the narrow part of the cell, indicating a high abundance of hydrogelator in that region of the cell. (D) DIC light microscopy image of the same cell of interest shown in (B, C), but after high-pressure freezing, freeze-substitution and resin-embedding; note that the Aclar pattern is still visible to guide trimming of the resin block before cutting ultrathin plastic sections (70 nm thick) that can be inspected in the transmission electron microscope (TEM). (E) Low magnification TEM image of the cell of interest shown in (B–D). (F) Higher magnification electron micrograph of the neck-region (red box in E) of the same cell shown in (B–E); the narrow neck-region of the cell corresponds to the area of highest fluorescence signal (in C); the image displays a large specimen area at relatively high resolution, because it is a “montage image” that was stitched together from 220 individual, high magnification image tiles. (G, H) High magnification electron micrographs of the (G) blue boxed area and (H) the red boxed area in (F); note the presence of low electron-dense pools (black arrowheads), presumably containing hydrogelator. Scale bars: 100 μm (A), 25 μm (B, C, D, E), and 5 μm (F), 250 nm (G, H).

Several facts help exclude the possibility that cellular segregation alone results in the agglomeration in the cells. First, the CLEM study reveals that not only the fluorescent molecular agglomerations are adjacent to each other, but also the fluorescent area super imposes with the molecular agglomeration shown in TEM. Second, if the agglomeration is induced by cellular segregation, these resulting vesicles should widely spread within the cytoplasm. But they localize in a confined area to indicate that the agglomeration is unlikely induced by cellular segregation. Third, we design and synthesize a third molecule, 3a (Fig. S9), which has a very similar structure to 1a and 2a. Specifically, 3a consists of a rhodamine group via the ε-lysine linkage. In a gelation test, we find that the solution of 3a fails to form a hydrogel after dephosphorylation (Fig. S10), indicating that 3a is unable to form nanofibers before and after dephosphorylation. When we incubate HeLa cells with 3a at the concentration of 500 μM, the cells are homogeneously shown in red instead of producing any agglomeration within cytoplasm (Fig. S11). This result further support that enzyme-instructed self-assembly result in the localization of the agglomeration of the hydrogelator of 1a.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the molecular assemblies of self-assembled small molecules behave drastically different from the individual molecules. The reported model system not only allows intracellular formation of nanostructures via enzyme-instructed molecular self-assembly, but also offers a new way for elucidating and utilizing the emerging properties of supramolecular assemblies of small molecules inside cells. For example, intracellular formation of molecular assemblies could be used selectively inhibit the growth of cells that overexpress certain enzymes.6, 7, 40 The further development of molecular self-assembly41–43 based approaches for understanding and modulating fundamental cellular process (e.g., proteostasis) and for exploring its potential applications in biomedicine (e.g., intracellular drug delivery44), may ultimately lead to a new way to regulate cellular functions. The small size of the precursors and the simplicity of the enzyme-instructed self-assembly process should also facilitate the delineation of the molecular details of the molecular assemblies from the complex cellular process.

Materials and Methods

A) Materials

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was purchased from Biomatik USA, LLC., dansyl chloride (DNS-Cl) from Sigma-Aldrich, 2- naphthylacetic acid and N-hydroxysuccinimide from Alfa Aesar, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodimide from Acros Organics USA, all amino acid derivatives from GL Biochem (Shanghai) Ltd. and ER-Tracker™ Red (glibenclamide BODIPY® TR) and SYTO® 85 orange fluorescent nucleic acid stain from Invitrogen™ and used according to the protocols.

B) Instruments

Fluorescence spectra on Shimadzu RF-5301-PC Fluorescence Spectrophotometer; LC-MS on Waters Acquity ultra Performance LC with Waters MICROMASS detector and ARES-G2 rheometer; electron microscopy was performed on a FEI Morgagni 268 TEM with a 1k CCD camera (GATAN, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) or a 300keV Tecnai F30 intermediate voltage TEM (FEI, Inc., Hillsboro, OR) with a 4k CCD camera (GATAN); confocal images on Leica TCS SP2 Spectral Confocal Microscope; MTT assay for cell toxicity test on DTX880 Multimode Detector.

C) General methods

Briefly, the in vitro hydrogelation test was monitored with the addition of ALP into each hydrogelator precursor solution. The resulting fibril structures were identified by TEM with general negative staining method. The concentrations of each compound inside cells were determined according to the integration of corresponding peak from LC-MS trace of the lysate of cells incubated at various conditions. For all confocal images, the cells were seeded on the Lab-Tek II chambered coverglass and treated with conditions as described in the main text.

D) Cell fragmentation27

600g, 10min: Pellet Sample N (Nuclei); 15,000g 5min: Pellet Sample M (Mitochondria, lysosomes, peroxisomes); 100,000g, 60min: Pellet Sample P (Plasma membrane, microsomal fraction (fragments of endoplasmic reticulum), large polyribsomes); 300,000g, 120min: Pellet Sample R (Ribosomal subunits, small polyribosomes); Supernatant Sample C: soluble portion of cytoplasm (Cytosol).

Pellets N, M, P and R were all re-dispersed in 200 μL of PBS for further test.

E) Sample preparation and electron microscopy of cells

Aclar discs with 1.5 mm diameter were punched out of Aclar film (EMS, #50426-10; Fort Washington, PA) and mounted on a Lab-Tek II Chambered Coverglass (#155379 Nalge Nunc International). HeLa cells were then seeded on the coverglass included on the Aclar discs and grown to less than confluent density in Minimum Essential Medium and 10% FBS (Invitrogen). Cells treated with the hydrogelator were incubated with the precursor for 48 hrs before light microscopy and EM preparation. Cells were imaged by phase contrast and/or fluorescent light microscopy using an inverted Leica SP2 Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope. After light microscopic imaging, the Aclar discs with the cells were transferred into one half of an aluminum planchettes covered with a drop of medium containing 150 mM sucrose as cryoprotectant for high-pressure freezing (Wohlwend, Switzerland), and the second half of the planchette was added to enclose the cells in a cavity with 0.1 mm of height. The samples were rapidly frozen using a Leica HPM-100 high-pressure freezer (Leica Microsystem, Vienna, Austria). The frozen cells were freeze-substituted at low temperatures over 3 days in a solution containing 1% osmium tetroxide (EMS), 0.5% anhydrous glutaraldehyde (EMS) and 2% water in anhydrous acetone (AC32680-0010 Fisher Scientific) using a Leica AFS-2 device. After the temperature was raised to 4°C the cells were infiltrated and embedded in EMbed 812-Resin (EMS). Ultrathin sections (~70 nm) were collected on slot grids covered with Formvar support film and post-stained with uranyl acetate (supersaturated solution) and 0.2% lead citrate, before being inspected using a FEI Morgagni 268 TEM with a 1k CCD camera (GATAN, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) or a 300keV Tecnai F30 intermediate voltage TEM (FEI, Inc., Hillsboro, OR) with a 4k CCD camera (GATAN). For large overviews of the cells at medium magnification we acquired montages of overlapping images in an automated fashion using the microscope control software SerialEM.45

For Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM), we grew cells on Aclar discs that were marked with a pattern that allowed tracking of cells of interest throughout the light microscopy and EM sample preparation. After locating cells of interest, e.g. those containing fluorescently labeled hydrogelator, by light microscopy, the cells were rapidly frozen, fixed and resinembedded as described above. For TEM analysis, the block was trimmed - guided by the pattern on the Aclar disc - so that only the quadrant containing the cells of interest remained for ultrathin sectioning. After post-staining of the sections, we recorded overview maps of the sections at low magnification in the TEM to localize again the cell(s) of interest, before recording images at higher magnification for the ultrastructural investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NSF (DMR 0820492) to BX and DN, by a HFSP grant (RGP0056/2008) and a NIH grant (R01CA142746) to BX, start-up funds from Brandeis University, and by NSF (MRI NSF 0722582) to DN. Light and electron microscopy was performed at the Brandeis imaging facilities. We thank Mr. Wenbo Pei for help on LC-MS experiments.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting Information. TEM images, LC-MS, rheology, fluorescent images, procedures for cell fractionation and EM sample preparation. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Fletcher DA, Mullins D. Cell Mechanics and the Cytoskeleton. Nature. 2008;463:485–492. doi: 10.1038/nature08908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. Alpha-Synuclein in Filamentous Inclusions of Lewy Bodies From Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia With Lewy Bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA. 1998;95:6469–6473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Actin, a Central Player in Cell Shape and Movement. Science. 2009;326:1208–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perng MD, Cairns L, van den Ijssel P, Prescott A, Hutcheson AM, Quinlan RA. Intermediate Filament Interactions can be Altered by HSP27 and Alpha B-Crystallin. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2099–2112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubinsztein DC. The Roles of Intracellular Protein-Degradation Pathways in Neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z, Liang G, Guo Z, Xu B. Intracellular Hydrogelation of Small Molecules Inhibits Bacterial Growth. Angew Chem IntEd. 2007;46:8216–8219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang ZM, Xu KM, Guo ZF, Guo ZH, Xu B. Intracellular Enzymatic Formation of Nanofibers Results in Hydrogelation and Regulated Cell Death. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3152–3156. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estroff LA, Hamilton AD. Water Gelation by Small Organic Molecules. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1201–1217. doi: 10.1021/cr0302049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terech P, Weiss RG. Low Molecular Mass Gelators of Organic Liquids and the Properties of Their Gels. Chem Rev. 1997;97:3133–3159. doi: 10.1021/cr9700282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulijn RV, Smith AM. Designing Peptide Based Nanomaterials. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:664–675. doi: 10.1039/b609047h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer PM, Krausz E, Lane DP. Cellular Delivery of Impermeable Effector Molecules in the Form of Conjugates with Peptides Capable of Mediating Membrane Translocation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:825–841. doi: 10.1021/bc0155115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zorn JA, Wille H, Wolan DW, Wells JA. Self-Assembling Small Molecules Form Nanofibers That Bind Procaspase-3 to Promote Activation. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19630–19633. doi: 10.1021/ja208350u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuang Y, Xu B. Disruption of the Dynamics of Microtubules and Selective Inhibition of Glioblastoma Cells by Nanofibers of Small Hydrophobic Molecules. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:6944–6948. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar RK, Yu XX, Patil A, Li M, Mann S. Cytoskeletal-like Supramolecular Assembly and Nanoparticle-Based Motors in a Model Protocell. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9343–9347. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Y, Shi JF, Yuan D, Xu B. Imaging Enzyme-Triggered Self-Assembly of Small Molecules Inside Live Cells. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1033. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sameiro M, Goncalves T. Fluorescent Labeling of Biomolecules with Organic Probes. Chem Rev. 2009;109:190–212. doi: 10.1021/cr0783840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmer M. Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP): Applications, Structure, and Related Photophysical Behavior. Chem Rev. 2002;102:759–781. doi: 10.1021/cr010142r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Quantum Dot Bioconjugates for Imaging, Labelling and Sensing. Nat Mater. 2005;4:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resch-Genger U, Grabolle M, Cavaliere-Jaricot S, Nitschke R, Nann T. Quantum Dots versus Organic Dyes as Fluorescent Labels. Nat Methods. 2008;5:763–775. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang K, Rodgers ME, Toptygin D, Munsen VA, Brand L. Fluorescence Study of the Multiple Binding Equilibria of the Galactose Repressor. Biochemistry. 1998;37:41–50. doi: 10.1021/bi972004v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li GW, Chen HY, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS. Quantifying E-coli Proteome and Transcriptome with Single-Molecule Sensitivity in Single Cells. Science. 2010;329:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.1188308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freudiger CW, Min W, Saar BG, Lu S, Holtom GR, He CW, Tsai JC, Kang JX, Xie XS. Label-Free Biomedical Imaging with High Sensitivity by Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy. Science. 2008;322:1857–1861. doi: 10.1126/science.1165758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Channon KJ, Devlin GL, MacPhee CE. Efficient Energy Transfer within Self-Assembling Peptide Fibers: A Route to Light-Harvesting Nanomaterials. J Am ChemSoc. 2009;131:12520–12521. doi: 10.1021/ja902825j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Revel S, Morris K, Adams DJ. Energy Transfer in Self-Assembled Dipeptide Hydrogels. Chem Commun. 2010;46:4267–4269. doi: 10.1039/c003052j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Z, Liang G, Xu B. Enzymatic Hydrogelation of Small Molecules. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:315–326. doi: 10.1021/ar7001914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JY, Gao Y, Kuang Y, Shi JF, Du XW, Zhou J, Wang HM, Yang ZM, Xu B. Dephosphorylation of D-Peptide Derivatives to Form Biofunctional, Supramolecular Nanofibers/Hydrogels and Their Potential Applications for Intracellular Imaging and Intratumoral Chemotherapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9907–9914. doi: 10.1021/ja404215g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JY, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Du XW, Shi JF, Xu B. D-Amino Acids Boost the Selectivity and Confer Supramolecular Hydrogels of a Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:542–545. doi: 10.1021/ja310019x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li JY, Kuang Y, Shi JF, Gao Y, Zhou J, Xu B. The Conjugation of Non-steroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAID) to Small Peptides for Generating Multifunctional Supramolecular Nanofibers/Hydrogels. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2013;9:908–917. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li JY, Li XM, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Du XW, Shi JF, Xu B. Self-delivery Multifunctional Anti- HIV Hydrogels for Sustained Release. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300041. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith C. Two Microscopes are Better Than One. Nature. 2012;492:293–297. doi: 10.1038/492293a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One Step at a Time: Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:944–957. doi: 10.1038/nrm2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Xu B. Versatile Small-Molecule Motifs for Self-Assembly in Water and the Formation of Biofunctional Supramolecular Hydrogels. Langmuir. 2010;27:529–537. doi: 10.1021/la1020324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, Kuang Y, Guo ZF, Guo ZH, Krauss IJ, Xu B. Enzyme-Instructed Molecular Self- Assembly Confers Nanofibers and a Supramolecular Hydrogel of Taxol Derivative. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13576–13577. doi: 10.1021/ja904411z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4. Garland Science; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendez AJ. Cholesterol Efflux Mediated by Apolipoproteins is an Active Cellular Process Distinct from Efflux Mediated by Passive Diffusion. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:1807–1821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dopp E, von Recklinghausen U, Hartmann LM, Stueckradt I, Pollok I, Rabieh S, Hao L, Nussler A, Katier C, Hirner AV, et al. Subcellular Distribution of Inorganic and Methylated Arsenic Compounds in Human Urothelial Cells and Human Hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:971–979. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frado LL, Craig R. Electron-Microscopy of the Actin-Myosin Head Complex in the Presence of Atp. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowak AP, Breedveld V, Pakstis L, Ozbas B, Pine DJ, Pochan D, Deming TJ. Rapidly Recovering Hydrogel Scaffolds from Self-Assembling Diblock Copolypeptide Amphiphiles. Nature. 2002;417:424–428. doi: 10.1038/417424a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang GL, Ren HJ, Rao JH. A Biocompatible Condensation Reaction for Controlled Assembly of Nanostructures in Living Cells. Nat Chem. 2009;2:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nchem.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huc I, Lehn JM. Virtual Combinatorial Libraries: Dynamic Generation of Molecular and Supramolecular Diversity by Self-Assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2106–2110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lehn JM. Perspectives in Supramolecular Chemistry-from Molecular Recognition towards Molecular Information-Processing and Self-Organization. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1990;29:1304–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitesides GM, Mathias JP, Seto CT. Molecular Self-Assembly and Nanochemistry-a Chemical Strategy for the Synthesis of Nanostructures. Science. 1991;254:1312–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1962191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee Y, Ishii T, Kim HJ, Nishiyama N, Hayakawa Y, Itaka K, Kataoka K. Efficient Delivery of Bioactive Antibodies into the Cytoplasm of Living Cells by Charge-Conversional Polyion Complex Micelles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:2552–2555. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mastronarde DN. Automated Electron Microscope Tomography Using Robust Prediction of Specimen Movements. J Struct Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.