Significance

The morphology of astrocytes places them as likely contributors to communication between nerve cells and blood vessels. They are reported to respond with few and slow Ca2+ elevations, which exclude them as possible participants in initiation of blood flow responses or synapse communication. We establish that astrocytes have fast responses in addition to the slow. These rapid, brief Ca2+ responses were present in a large proportion of astrocytes. We were able to observe these changes due to a signal enhancement analysis, which is useful when responses are small compared with baseline activity. Our findings indicate a higher sensitivity than generally believed of astrocytes.

Keywords: neurovascular coupling, Ca2+ imaging, functional imaging, sensory barrel cortex

Abstract

Increased neuron and astrocyte activity triggers increased brain blood flow, but controversy exists over whether stimulation-induced changes in astrocyte activity are rapid and widespread enough to contribute to brain blood flow control. Here, we provide evidence for stimulus-evoked Ca2+ elevations with rapid onset and short duration in a large proportion of cortical astrocytes in the adult mouse somatosensory cortex. Our improved detection of the fast Ca2+ signals is due to a signal-enhancing analysis of the Ca2+ activity. The rapid stimulation-evoked Ca2+ increases identified in astrocyte somas, processes, and end-feet preceded local vasodilatation. Fast Ca2+ responses in both neurons and astrocytes correlated with synaptic activity, but only the astrocytic responses correlated with the hemodynamic shifts. These data establish that a large proportion of cortical astrocytes have brief Ca2+ responses with a rapid onset in vivo, fast enough to initiate hemodynamic responses or influence synaptic activity.

Brain function emerges from signaling in and between neurons and associated astrocytes, which causes fluctuations in cerebral blood flow (CBF) (1–5). Astrocytes are ideally situated for controlling activity-dependent increases in CBF because they closely associate with synapses and contact blood vessels with their end-feet (1, 6). Whether or not astrocytic Ca2+ responses develop often or rapidly enough to account for vascular signals in vivo is still controversial (7–10). Ca2+ responses are of interest because intracellular Ca2+ is a key messenger in astrocytic communication and because enzymes that synthesize the vasoactive substances responsible for neurovascular coupling are Ca2+-dependent (1, 4). Neuronal activity releases glutamate at synapses and activates metabotropic glutamate receptors on astrocytes, and this activation can be monitored by imaging cytosolic Ca2+ changes (11). Astrocytic Ca2+ responses are often reported to evolve on a slow (seconds) time scale, which is too slow to account for activity-dependent increases in CBF (8, 10, 12, 13). Furthermore, uncaging of Ca2+ in astrocytes triggers vascular responses in brain slices through specific Ca2+-dependent pathways with a protracted time course (14, 15). More recently, stimulation of single presynaptic neurons in hippocampal slices was shown to evoke fast, brief, local Ca2+ elevations in astrocytic processes that were essential for local synaptic functioning in the adult brain (16, 17). This work prompted us to reexamine the characteristics of fast, brief astrocytic Ca2+ signals in vivo with special regard to neurovascular coupling, i.e., the association between local increases in neural activity and the concomitant rise in local blood flow, which constitutes the physiological basis for functional neuroimaging.

Here, we describe how a previously undescribed method of analysis enabled us to provide evidence for fast Ca2+ responses in a main fraction of astrocytes in mouse whisker barrel cortical layers II/III in response to somatosensory stimulation. The astrocytic Ca2+ responses were brief enough to be a direct consequence of synaptic excitation and correlated with stimulation-induced hemodynamic responses. Fast Ca2+ responses in astrocyte end-feet preceded the onset of dilatation in adjacent vessels by hundreds of milliseconds. This finding might suggest that communication at the gliovascular interface contributes considerably to neurovascular coupling.

Results

Fast Ca2+ Activity Occurs in Astrocytes.

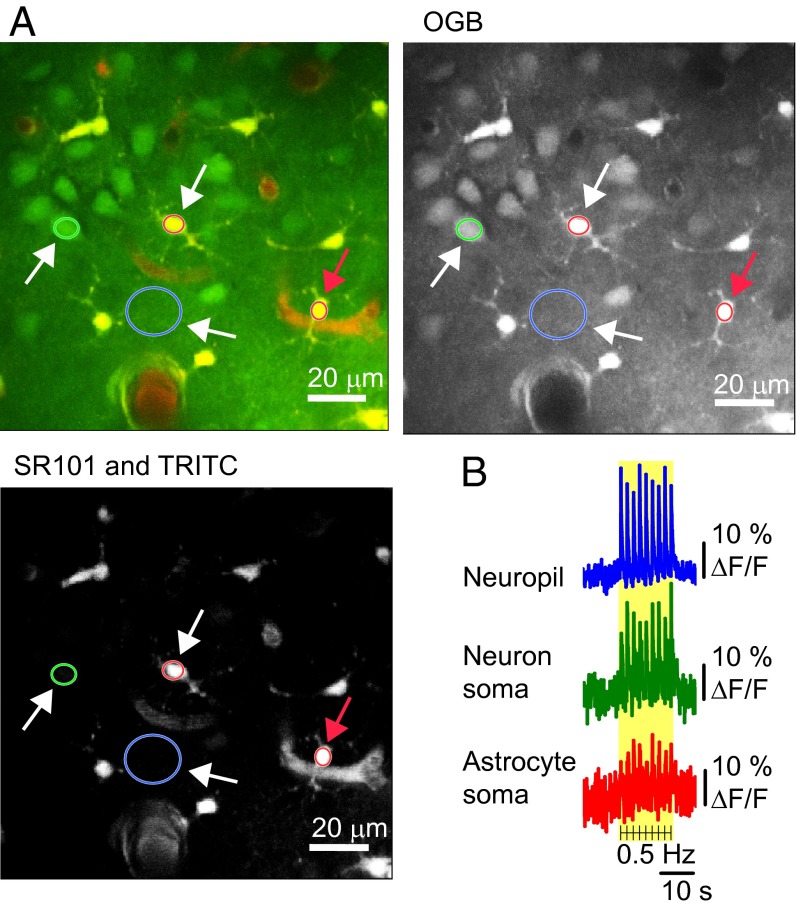

We recorded intracellular Ca2+ responses in astrocytes and neurons by 2-photon microscopy (2-PM) during activation of the whisker barrel cortex. Whisker pad stimulation was used to activate the contralateral somatosensory cortex as indicated by a hemodynamic response. With intrinsic optical signal, the increased blood volume appeared as darkening of the blood vessels in the activated area (18, 19) (Fig. S1). The increases in blood flow occurred within the first second of stimulation, as previously reported (9, 12, 20, 21). After verification that the neurovascular response was preserved, the center of the responsive cortex was stained with the membrane-permeable Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green Bapta-1/AM (OGB) (22) and the astrocyte-specific dye sulforhodamine 101 (SR101) (23) (Fig. 1A). Based on double-staining and the morphology of cellular elements, regions of interest (ROIs) were defined as neuron somas, neuropil, and astrocyte somas, processes, or end-feet (Fig. 1A). Whisker-pad stimulation evoked rapid Ca2+ fluctuations in the neuropil and neuronal somas, concurrent with Ca2+ increases in astrocyte somas in the same focal plane. The fast Ca2+ fluorescence signal was observed in both astrocytes and neurons for every stimulation (Fig. 1B and Movie S1), suggesting rapid cytosolic Ca2+ transients in both cell types.

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ imaging during somatosensory stimulation reveals that both astrocytes and neurons have fast response patterns. (A) Double labeling allows distinction between astrocytic and neuronal structures. Layers II/III of the whisker barrel cortex were loaded with astrocyte-specific dye SR101 (red) in combination with the Ca2+ fluorophore OGB (green) and vascular TRITC-dextran (red). Regions of interest (ROIs) are marked with colored rings: one neuronal soma (green), two astrocyte somas (red), and one neuropil region (blue). The fluorescence changes are shown in B (white arrows) and in Fig. 2A (red arrow). (Scale bar: 20 µm.) (B) Data traces from one mouse during 15-s, 0.5-Hz stimulation. Each black line indicates stimulations; the yellow area marks the stimulation period. The fluorescence changes are given in percentage of baseline Ca2+ activity (ΔF/F0).

Astrocytic Ca2+ Activity Consists of Fast Responses Combined with Slow Augmentations.

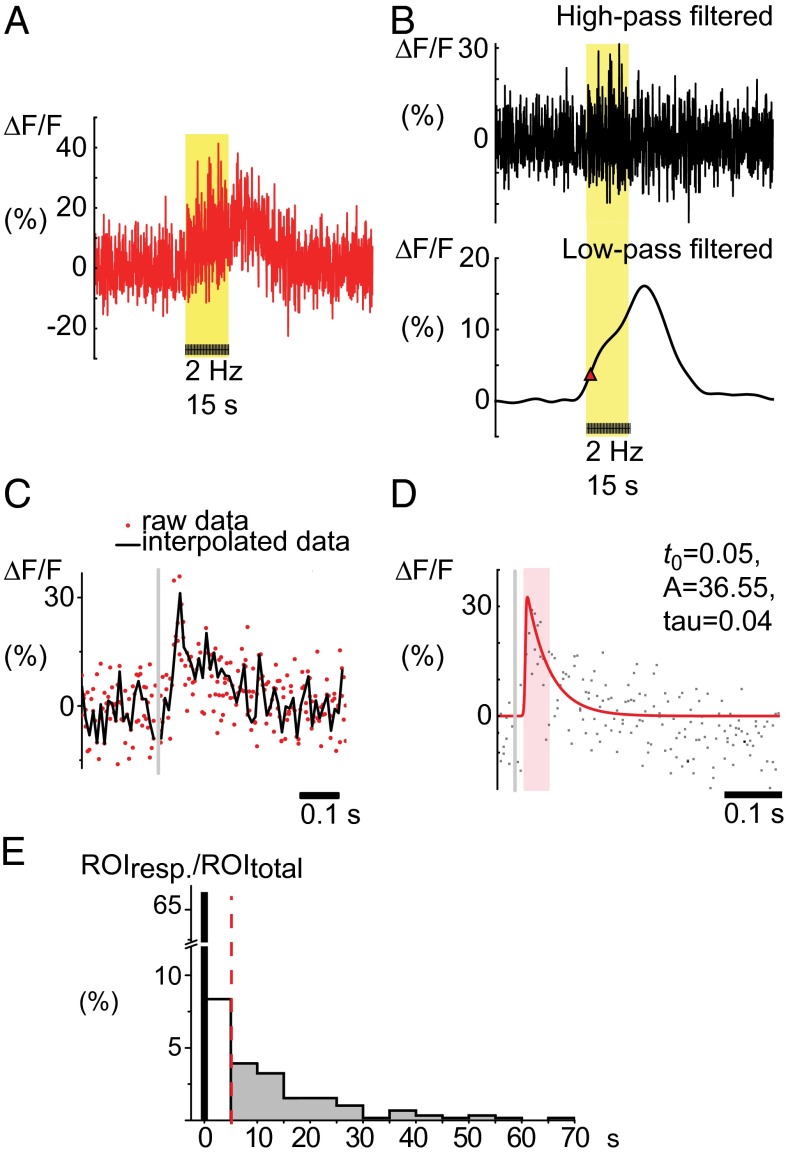

Because the prevalence of rapid elevation of Ca2+ in cortical astrocytes is disputed, we investigated the stimulation-dependent Ca2+ elevation in astrocytes in more detail (Fig. 2A). These elevations could be separated into fast and slow components by low-pass filtering (Fig. 2B). The high-frequency astrocytic Ca2+ signal was exposed by superimposing data points from all frames during a train of stimulation in accordance with the delay from each stimulus, followed by interpolation (Fig. 2C, Fig. S2, and Movie S2). This visualization allowed us to characterize the fast Ca2+ response with respect to time of onset, amplitude, and decay time, as illustrated in Fig. 2D. The time-lock to the stimulus was the key to identifying the fast astrocytic Ca2+ signals. In addition, the observation that superposition of data points increased the signal-to-noise ratio suggested that the signal represented a series of similar temporal waveforms trapped in different frames of image scanning. The onset of the fast astrocytic Ca2+ response occurred with a mean delay of 98 ms (± 8 ms, 95% confidence interval) after stimulus onset. The slow component of the response, which was seen over the entire train of stimulation, was observed with a time latency of 14.4 s (± 2.2 s) (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Stimulation-evoked astrocyte Ca2+ signals can be split into high- and low-frequency components. (A) Representative example of Ca2+ activity recorded in an astrocytic soma; see red arrow in Fig. 1A, in percentage of baseline Ca2+ activity (ΔF/F0). The yellow area marks whisker-pad stimulation at 2 Hz for a period of 15 s. (B) The astrocyte Ca2+ signal (A) separated by wavelet transformation to a high-frequency (Upper) and a low-frequency component (Lower). The red triangle indicates the start of the slow Ca2+ response, as defined by the max slope before the main peak. (C) The high-frequency response interpolated as a single fast Ca2+ signal by superimposing data from the 15-s train of stimulation; see Movie S2. Red dots represent data points collected at different times after repeated stimuli; the black line represents the interpolated signal. The gray line marks the time of the single stimulation. (D) The fast Ca2+ signal fitted so that the decay time of the signal (tau) can be estimated. (E) Latency of astrocyte cell body response times for the evoked fast and induced slow components expressed as a percentage of all astrocytes. The histogram shows great variation in latency time to onset of slow responses but also that a subset of astrocytes responded within the first 5 s of stimulation (154 astrocytes, 33 mice, 2 Hz stimulation frequency).

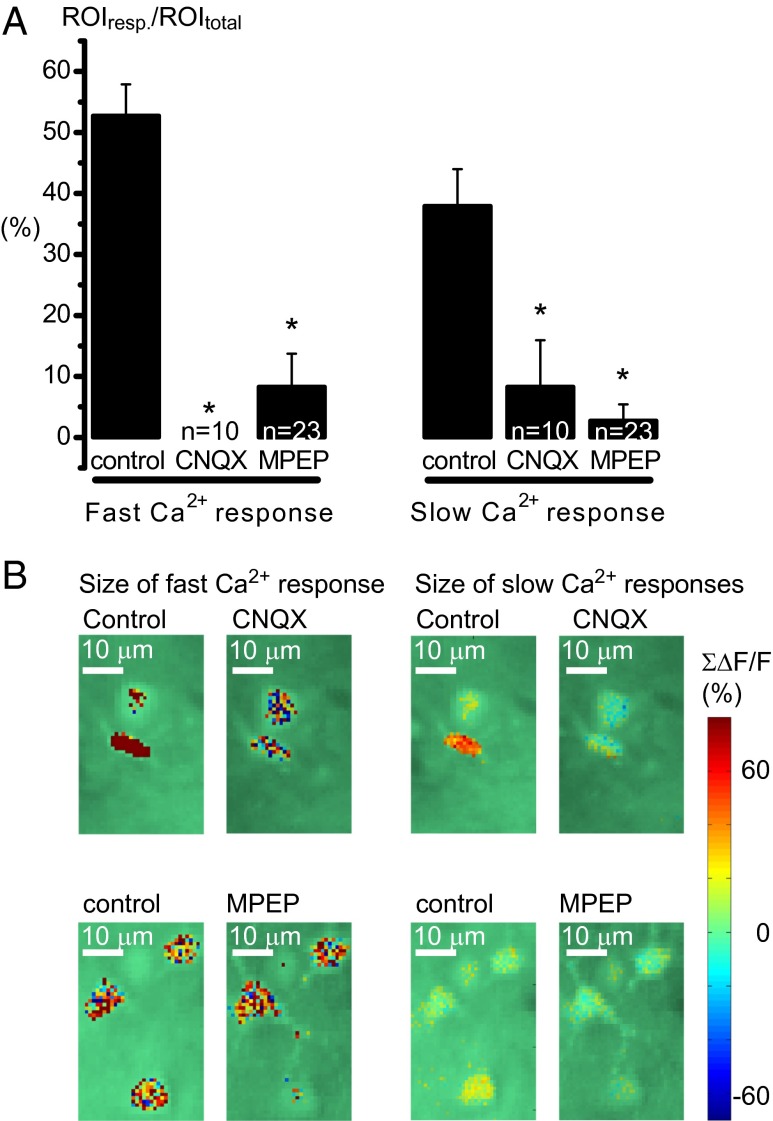

The fast evoked astrocytic Ca2+ signals were more prevalent than the induced slow signals. During stimulation for 15 s at 2 Hz, 66.2% of astrocyte somas displayed evoked, fast Ca2+ responses whereas slow responses were initiated in only 8.4% of astrocytes during the first 5 s after stimulation and in 13.3% during the following 60 s (Fig. 2E). The origin of the two components of the astrocytic Ca2+ response was examined by use of two glutamate receptor antagonists. The fast and slow astrocytic Ca2+ responses were both significantly diminished when the AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium salt; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied (Fig. 3). Correspondingly, the neuronal Ca2+ responses and the local field potentials (LFP) were silenced. This result showed that astrocytic activation depended on recruitment of cortical neurons by the afferent synaptic input. The effect was more pronounced on the fast signals that were completely blocked; in comparison, the slow Ca2+ responses were reduced. The mGluR5a receptor antagonist MPEP also dramatically reduced both fast and slow astrocytic Ca2+ activity (Fig. 3), which indicates an mGluR-mediated signaling pathway for astrocyte activation.

Fig. 3.

Glutamate receptor antagonists reduced the prevalence of both fast and slow astrocytic Ca2+ signals. (A) The AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX and the mGluR5a antagonist MPEP significantly reduced the mean of ROIs responding both with fast and slow Ca2+ signals, but not to the same degree. The percentage of responding ROIs during 15-s, 2-Hz whisker stimulation was studied in n = 10 ROIs from three animals for CNQX and n = 23 ROIs from six animals for MPEP. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Examples of drug effects in percentage of baseline Ca2+ activity (ΔF/F0) in some astrocytes using the calcium indicator OGB and 2-Hz stimulation of the whisker pad. The size of the Ca2+ responses, in astrocytic structures only, is shown in color scale overlaid 2-PM images of the field of view. Images on the Left show the size of the sum of the fast Ca2+ signal 10 to 120 ms after stimulation with or without drugs; images on the Right are of a sum of part of the slow astrocytic Ca2+ signals after 4 s of stimulation. (Scale bar: 10 µm.)

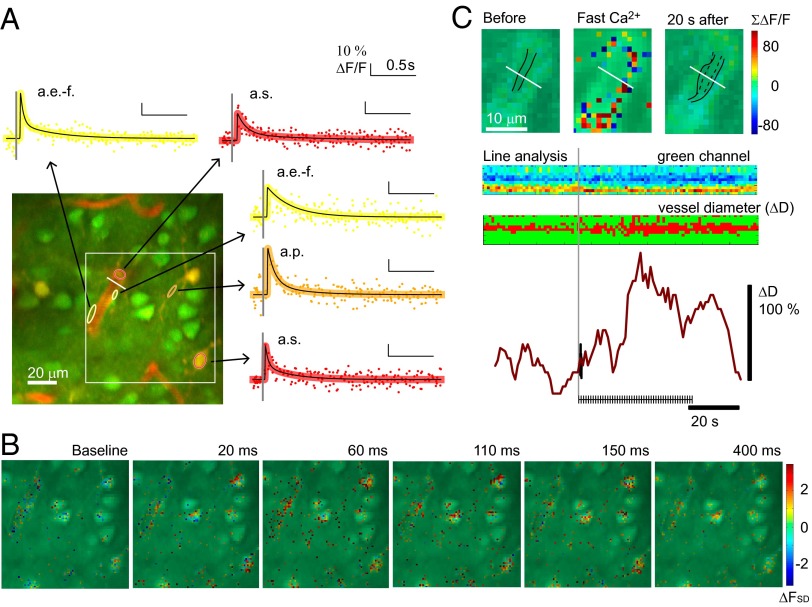

Fast Ca2+ Signals Occur in All Parts of Astrocytes, Including Astrocyte End-Feet Next to Local Vasodilatation.

Next, we investigated the fast Ca2+ signal from astrocyte somas, processes, and end-feet. Significant, fast Ca2+ signals were observed in all subcellular elements (Fig. 4A and Movie S3), as fluorescence changes greater than 2 standard deviations (SDs) beyond baseline fluorescence (FSD) (Fig. 4B). The evoked signals had the same appearance, with fast onset and short duration in all three ROI types. The fast Ca2+ response in the end-feet was of particular interest because dynamic changes in this subcellular element have been claimed to be a major factor in the control of CBF (6). This idea was supported by the occurrence of vasodilatation following fast Ca2+ responses in the adjacent end-feet (Fig. 4C and Fig. S3). The responsiveness of end-feet (67.9 ± 12%) matched that of the somas (67.4 ± 12%) whereas astrocyte processes were slightly but significantly more reactive (74.5 ± 11%, P = 0.018, ANOVA). Stimulation-induced vasodilatation was observed in 21 vessels (15 mice). Fast Ca2+ responses could be observed in astrocytic end-feet enveloping or contacting the dilating vessel in 77% of these cases. Although the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients declined with increased stimulus frequency, the average response at 5 Hz stimulation was still well above 2 FSD at 2.7 ± 0.07 FSD for astrocyte somas, 2.66 ± 0.09 FSD for astrocyte processes, and 2.65 ± 0.12 FSD for end-feet. The attenuation of the fast astrocytic Ca2+ signals with increased stimulation frequency correlated with the neuropil Ca2+ activity (Fig. S4). This finding opened the possibility that we erroneously assigned fast Ca2+ signals to astrocytes that stemmed from activity in the neuropil.

Fig. 4.

Identification of fast Ca2+ signals in astrocyte soma, processes, and end-feet in response to single stimuli and before vessel dilatation. (A) Examples of fast Ca2+ signals evoked by 15-s whisker-pad stimulation at 0.5 Hz averaged within ROIs in an OGB/SR101-stained preparation; astrocyte soma (a.s., indicated by red ring), processes (a.p., orange ring), and end-feet (a.e.-f., yellow ring). The arrows point to fitted interpolated signals from each ROI, shown with a black line and colored dots that represent original data points. The gray line marks the time of the stimulation. The fluorescence changes are given in percentage of baseline Ca2+ activity (ΔF/F0). The white square indicates the area shown in B, and the white line marks the line analysis shown in C. (B) Location of Ca2+ signal in astrocytic areas only, during 15-s stimulation at 0.5 Hz. Pixels were defined as astrocytic if the SR101 staining was 2 SD above the level of the entire image. The color scale of the pixels gives the Ca2+ responses measured in SDs of baseline activity (ΔFSD). Responses ≥2 ΔFSD were considered significant. (C) Same vessel as in A shown before and during 15-s stimulation at 3 Hz, with the summed fast Ca2+ response from 10 to 120 ms after stimulation in ΔF/F0. Below are the results from a line analysis of the raw OGB channel and filtered as pixels below or above 85% of the average intensity (u < ū*0.85). The traces at the bottom show the sum of these pixels in % of baseline (dark red) and the first fast Ca2+ response in the adjacent astrocytic end-feet (black).

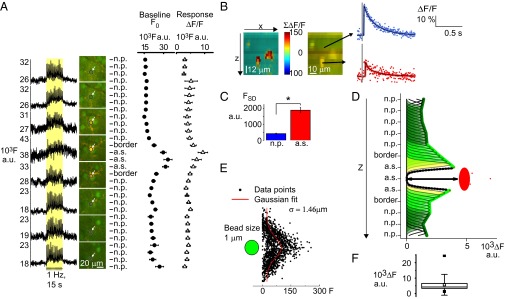

Neuropil Ca2+ Activity Below or Above Astrocytic Cell Bodies Does Not Explain Fast Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals During Stimulation.

To examine whether the fast Ca2+ signals that we assigned to astrocytes were instead fluorescence from the neuropil in other focal planes, 2-photon images were taken 4 µm apart along the z axis during repeated stimulations. The activity in the same ROI was recorded as the focus changed from the neuropil to astrocyte border, to astrocytic soma, to astrocyte border, and back to the neuropil (Fig. 5A). The baseline fluorescence was higher in astrocytic cell bodies than in the neuropil because of differences in OGB uptake (Fig. 5A, Left; note differences in scale of y axis). In addition, in most recordings, the absolute maximal fluorescence level of the evoked Ca2+ responses was higher in astrocyte soma than in the neuropil (Fig. 5A, Right). After normalization to baseline and interpolation of the fast signals, neuropil responses might in some cases be larger than astrocytic responses because neuropils respond more consistently when stimulated (Fig. 5B). In the unfiltered recording, the fast, stimulation-evoked astrocytic Ca2+ transients were less conspicuous (Fig. 5A, Left) because of the high Ca2+ activity during the baseline period, measured in units of SD of the mean (1,887 mean, SD ± 169, n = 32 animals). This value was ∼4 times higher (P < 0.001) than in the neuropil (414 mean, SD ± 32, n = 32 animals) (Fig. 5C), which explains why fast Ca2+ signals are commonly perceived in neuropil but not in astrocytes.

Fig. 5.

ROI-based laminar analysis of Ca2+ activity during stimulation localizes origin of fast signals to active astrocytic cell bodies, uncontaminated by neuropil signals. (A) OGB- and SR101-loaded 2-PM images were taken during stimulation in separate experiments in which the focal plane was changed at 4-µm intervals. The double stain allowed us to record localized activity in the same ROI as the focus changed from the neuropil (n.p.) to astrocyte border, to astrocytic soma (a.s.), to astrocyte border, and back to the neuropil (n = 16 ROIs from three animals). Leftmost shows the raw fluorescent Ca2+ signal at neuropil and astrocyte locations in arbitrary units (a.u.) whereas Center shows the images. In Right are the mean values from different levels from all 16 ROIs included in this study. The baseline fluorescence (●) was higher in astrocytic soma than in the neuropil, and, during stimulation, the Ca2+ response (Δ) was larger in the astrocyte soma than in the neuropil. (B) Fast Ca2+ signals from astrocytes along the z axis. The stack is recorded at different depths of z. The activity is shown in pixels defined as astrocytic by a > 2 SD SR101. The Ca2+ response is shown in percentage of baseline (ΔF/F0), summed from 10 to 120 ms after stimulation. To the Right is the same image in OGB/SR101. The arrow points to interpolated fast Ca2+ signal in ΔF/F0 from an ROI inside and above the astrocyte. (C) The baseline fluorescent level of activity was higher in astrocytes than in neuropil. The baseline Ca2+ activity was estimated as the mean of the SD in the fluorescence signal (FSD). FSD was much higher in astrocyte somas (n = 151) than in neuropil (n = 115) in 32 animals. Error bars in SEM. (D) The influence of neuropil fluorescence on astrocyte Ca2+ signals during evoked activity is negligible. For each focus level of experiment, areas without a clear view of the astrocyte soma were considered to be neuropil. The contribution from each such area to the center of the astrocyte was estimated by Gaussian distribution (green arcs), based on size of the point spread function of the system. The arrow indicates the distance between summed fluorescence contributed from neuropil (black stippled line) due to point spread of fluorescence along the z axis and the level of fluorescence inside the astrocyte soma (red). (E) The width of the point spread function was found to be σ = 1.46 µm as indicated by imaging of 1-µm beads under the same conditions as during the experiments (n = 20 beads). (F) The averaged difference in raw fluorescence levels (n = 28 ROIs), error bars in SD; the black squares show the max and min values and the white square the mean difference in fluorescence.

Despite the large difference in the level of fluorescence emitted from neuropil and astrocytes, neuropil still might have been influencing astrocytic signals because of the inherent inaccuracy of fluorescence microscopy. Especially along the z axis, the effect of the point spread function (PSF) introduces dispersion of the signal (24). The size of the axial distribution width of our system along the x, y, and z axes was estimated by scanning of fluorescent micro beads (24, 25) and was found to be 1.46 µm along the z axis, and 0.20 and 0.29 µm along the x and y axes, respectively (Fig. 5E). This information was used to estimate how much fluorescence emitted from the neuropil above and below the astrocytes contributed to the fluorescent signal recorded from the center of the astrocyte soma (Fig. 5D). The difference between the total fluorescence added from neuropil and the level of fluorescence in the astrocyte was large, 5,668 ± 851 in arbitrary fluorescence units (a.u.F, P < 0.001, in n = 28 ROIs for each sampling above, in, and below an astrocyte) (Fig. 5F). Thus, the level of fluorescence recorded from the astrocyte somas during stimulation could not be explained by neuropil Ca2+ responses. For this reason, we conclude that fluorescence contamination from the neuropil along the z axis did not explain the fast Ca2+ signals in astrocyte somas.

An Astrocyte-Specific Ca2+ Indicator Validates Fast Ca2+ Signals in Astrocytes.

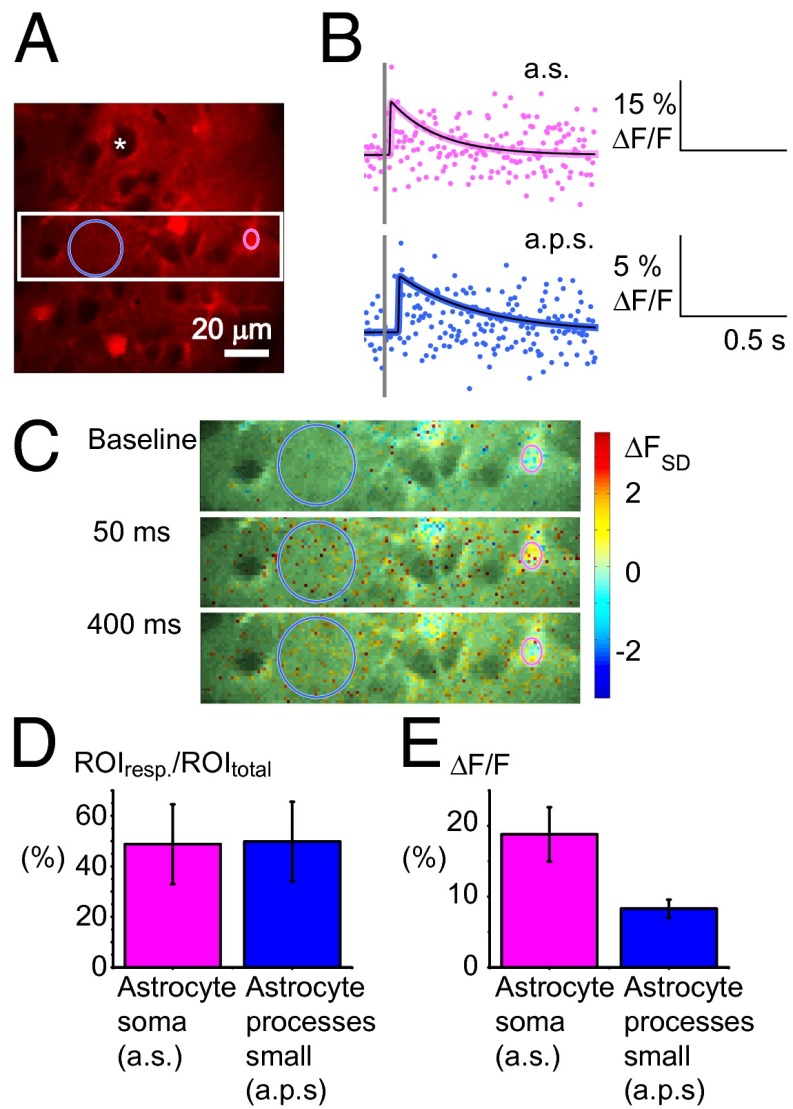

To further ensure that the observed Ca2+ changes originated from astrocytes, we applied Rhod2, a Ca2+ indicator that has been shown to enter only astrocytes (26, 27) (Fig. 6). The preference of tetramethylrhodamine derivates like Rhod2 for astrocytes (28) was evident in our experiments, in which neuronal somas appeared as black circles without fluorescence (Fig. 6A, white asterisk); in contrast, astrocyte somas were clearly labeled (Fig. 6A). Two classes of ROIs were defined, astrocyte somas and small astrocyte processes (Fig. 6A), both of which demonstrated fast, brief Ca2+ signals (Fig. 6 B and C). The Ca2+ responses in small astrocytic processes were examined with ROIs that corresponded in size and position to the ROIs used to analyze neuropil responses in the OGB-loaded cortex. Ca2+ signals in ROIs obtained with Rhod2 resembled responses from OGB-loaded astrocytic somas (Fig. S4). The signals were not as frequent (Fig. 6D) or of the same magnitude as those observed with OGB (Fig. 6E); however, identical response patterns were observed with respect to stimulation frequency and time delay from stimulation to the peak Ca2+ response of 102.9 ms (± 7.0, n = 32 animals) for astrocyte soma and 96.0 ms (± 9.4, n = 32 animals) for small astrocytic processes. The average maximum response amplitude was >2 FSD for all stimulation frequencies, confirming that astrocytes responded with fast Ca2+ signals.

Fig. 6.

Fast Ca2+ transients in response to somatosensory stimulation in astrocytes specifically stained with Rhod2. (A) A 2-PM image from layers II/III of the whisker-barrel cortex surface-loaded with Rhod2. The pink ring encircles an astrocytic soma ROI, and the blue ring depicts an ROI containing small astrocyte processes. The white asterisk indicates the black shadow of an unstained neuronal soma. The white square marks an area enlarged in C. (Scale bar: 20 µm.) (B) Interpolated fast Ca2+ signals during 15-s, 1-Hz whisker-pad stimulation, in astrocytic soma (a.s.) and small astrocytic processes (a.p.s.) in percentage of baseline fluorescence levels (ΔF/F0). The gray line indicates the stimulation time. (C) Time series of images showing fast Ca2+ activity in Rhod2-stained tissue. The pixel color scale shows the Ca2+ responses measured in SDs of baseline activity (ΔFSD). Responses ≥2 ΔFSD were considered significant. (D) Approximately half of the Rhod2-stained ROIs responded with fast Ca2+ signals during stimulation independently of the stimulus frequency. Mean of percentage of responding ROIs (n = 12), error bars in SE of proportions. (E) Mean maximum Ca2+ signals in percentage of baseline activity (ΔF/F0) in ROIs that responded at each stimulation frequency. The fast Ca2+ responses were bigger in astrocyte soma than in small processes (n = 12 mice).

Of note, the evoked, fast Rhod2 fluorescence signals from the small astrocytic processes were slower than OGB signals in the neuropil (Fig. 7C). The Ca2+ signals obtained using Rhod2 were derived from small astrocytic processes so this slowness provided indirect evidence that Ca2+ activity recorded in the OGB-stained neuropil stemmed primarily from neuronal dendrites rather than from astrocytic processes.

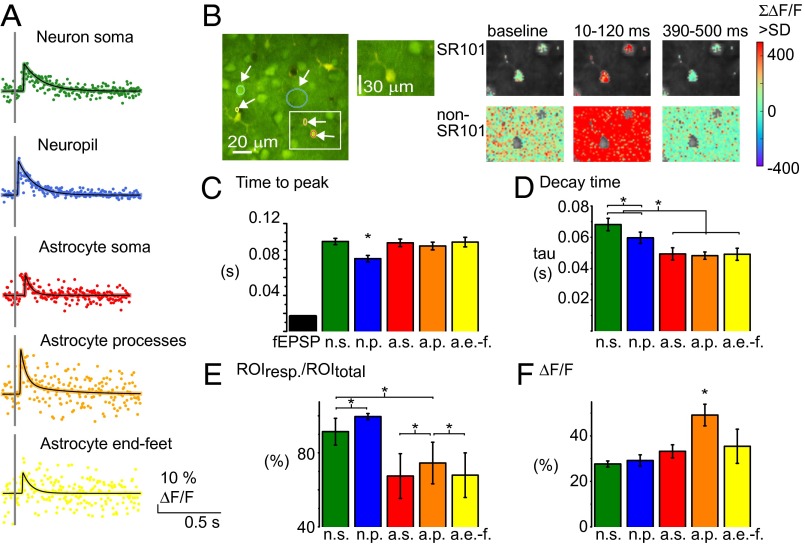

Fig. 7.

Fast Ca2+ signals exist both in neurons and astrocytes but diverge with respect to size, amplitude, prevalence, and timing. (A) Examples of Ca2+ signals from five different ROI types. Colored dots represent data points collected at different times after repeated stimuli. Black lines represent the fitted, interpolated signal. Scale bars depict fluorescence changes in percentage of the baseline activity (ΔF/F). (B) Time series of 2-PM images taken in cortical layers II/III in whisker-barrel cortex bulk-loaded with OGB (green) and surface-loaded with SR101 (red). ROIs shown in B: neuronal soma (green), neuropil (blue), astrocytic soma (red), astrocytic process (orange), and astrocytic end-feet (yellow). Sum of Ca2+activity, significantly higher than in the baseline period (>2 FSD), in 110-ms periods before, during, and after the fast Ca2+ response. Statistically significant responses are shown in the Upper row for astrocytic and Lower row for nonastrocytic (neuronal/neuropil) areas. A structure was defined as astrocytic if the SR101 staining was >2 SD of the level in the entire image and if <2 SD classified as non-SR101 pixels. Pixels not evaluated are gray in the images. (C) Mean latency of peak of Ca2+ signal and fEPSP during whisker-pad stimulation. The evoked fEPSP preceded the Ca2+ signals by 60–80 ms, and the neuropil peaked ∼20 ms before other cellular structures (P < 0.001; n = 32 animals). (D) Decay time (tau) of the fast Ca2+ responses in different ROIs. The fast Ca2+ signal lasted longest in neuron soma and neuropil (n = 32 animals, 1-Hz stimulation). (E) The percentage of ROIs responding with a fast Ca2+ signal at 1-Hz stimulation (>2 FSD). Same color code as in D (n = 15 animals). Error bars in SE of proportions. (F) Amplitude of Ca2+ activity in % of baseline. The mean maximum of the ROIs with Ca2+ signal >2 FSD shows the signal to be of equal size in astrocytic and neuronal structures (n = 15 animals). All error bars represent SEM; for number of ROIs included, see Table 1.

Fast, Brief Ca2+ Signals Differ in Size and Responsiveness Among Different Cellular Structures.

Next, we compared the temporal aspect of fast, brief Ca2+ signals in neuropil, neuronal somas, and astrocyte somas, processes, and end-feet (Fig. 7 A and B). The first ROI to respond to stimulation was the neuropil (Fig. 7B). Ca2+ responses in the neuropil peaked at 80.9 ± 3.6 ms after stimulation (Fig. 7C). In comparison, the time delay to peak Ca2+ elevations was ∼100 ms in neuron soma and in astrocyte somas, processes, and end-feet (Fig. 7C). Thus, the maximal neuropil Ca2+ signal preceded the peak of adjacent astrocyte and neuronal subcellular elements by ∼20 ms (P < 0.001, n = 32 animals) (Fig. 7C). This delay may represent the time latency for a synaptic input to trigger Ca2+ signals in adjacent tissue. The maximum amplitude of the Ca2+ signal varied between cells in both neurons and astrocytes and among subcellular compartments, but, in all ROIs, the mean response exceeded 2 FSD, being in neuropil 7.14 FSD (± 0.04%, n = 1,746 ROIs), in neuron soma 3.89 FSD (± 0.16%, n = 501 ROIs), in astrocyte soma 3.26 FSD (± 0.05%, n = 467 ROIs), processes 3.73 FSD (± 0.08%, n = 438 ROIs), and end-feet 3.33 FSD (± 0.07%, n = 265 ROIs).

We observed a significant difference in Ca2+ responsiveness among the cell types and structures, defined as the percentage with ΔF > 2 FSD (ANOVA, P < 0.05), except between astrocyte somas and end-feet (Fig. 7E). The responsiveness was highest in the neuropil, as 99.6% of ROIs (± 0.02%, n = 64 in 15 animals) responded above the threshold to stimulations at 1 Hz. The astrocytic somas were the least responsive, with fast Ca2+ signals in 67.4% of ROIs (± 0.12%, n = 74 in 15 animals). Increased stimulation frequency did not significantly influence responsiveness in any of the studied structures although it did have an effect on the size of the evoked Ca2+ responses during stimulation trains with stimulation frequencies of 2 Hz or higher (Fig. S4). This effect on Ca2+ responses was comparable with the effect of increased stimulation frequency on LFP size previously observed (21). Maximum amplitude (ΔF/F0) of the evoked Ca2+ responses ranged from 25% to 35% in all structures, except astrocyte processes, which had significantly higher amplitude (Fig. 7F). We used the OGB fluorescence values to estimate the level of the Ca2+ responses. When the OGB/SR101 ratio was used to compensate for possible movements, the size of the fast responses was not reduced in the astrocytic processes and end-feet and was reduced only to some degree in the astrocyte soma (Fig. S5). This result supported the finding that the size of the ΔF/F0 responses did not differ between ROIs. In contrast, we observed variations in the decay time in the different structures (Fig. 7D). The decay time (tau) was significantly longer in neuronal somas (68.2 ± 3.9 ms) and neuropil (59.7 ± 3.6 ms) than in astrocyte somas (49.4 ± 3.9 ms), processes (48.2 ± 2.3 ms), and end-feet (49.2 ± 3.9 ms) (n = 32 animals, ANOVA, P = 4.3 × 10−6), showing that the signal lasted longer in neurons than in astrocytes.

Neuronal and Astrocytic Fast Ca2+ Responses Correlate with Synaptic Excitation but only the Astrocytic Response Correlates with Hemodynamic Responses.

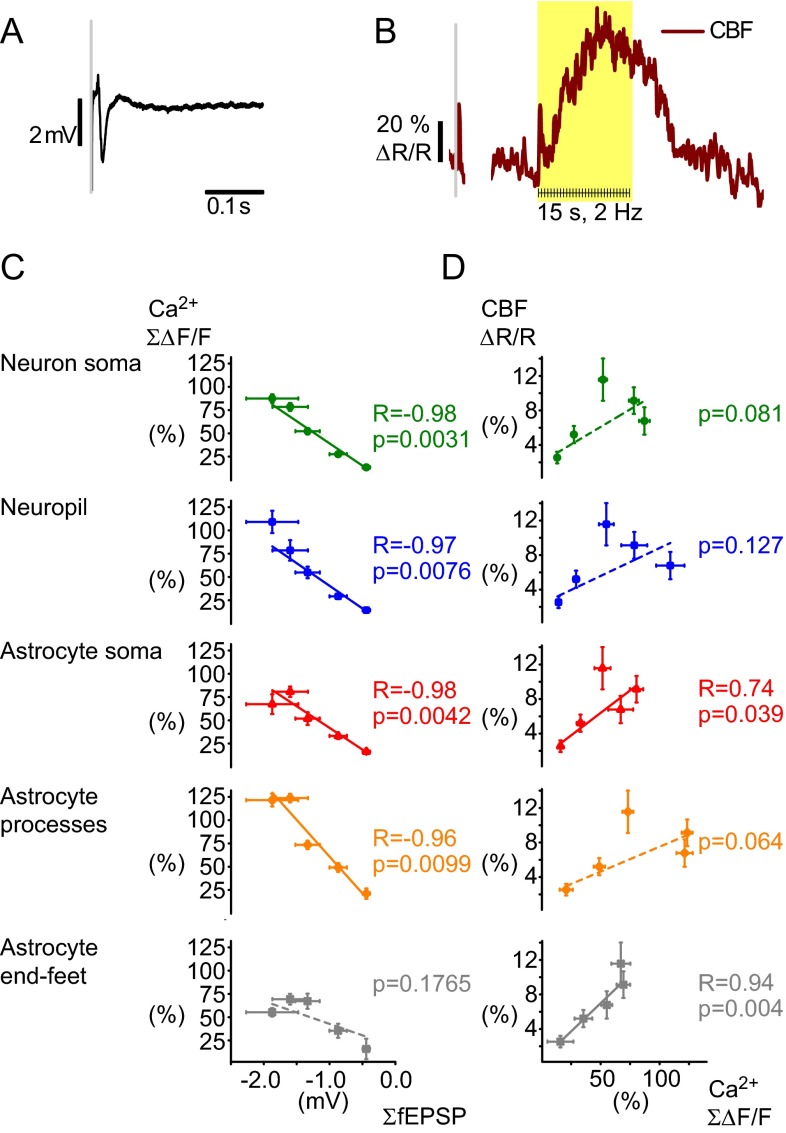

To estimate whether fast astrocytic Ca2+ responses contributed to the coupling between synaptic activity and blood flow responses, fast astrocytic Ca2+ signals were correlated with field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) (Fig. 8A) and CBF responses (Fig. 8B) (1, 4, 29, 30). We regarded the minimum of our extracellular recorded LFPs as reflecting the fEPSPs. First, the sum of the evoked Ca2+ response peaks was correlated with the sum of the response amplitudes of the fEPSPs at different stimulation frequencies (Fig. 8C). The two parameters were found to be linearly correlated in both neuropil (R2 = 0.91, P = 7.6 × 10−3, n = 15 animals, Pearson’s correlation), neuron somas (R2 = 0.95, P = 3.1 × 10−3, n = 15 animals, Pearson’s correlation), astrocyte somas (R2 = 0.94, P = 4.2 × 10−3, n = 15 animals, Pearson’s correlation), and astrocyte processes (R2 = 0.89, P = 9.9 × 10−3, n = 15 animals, Pearson’s correlation), but not in astrocyte end-feet (R2 = 0.34, P = 0.06, n = 15 animals, Pearson’s correlation) (Fig. 8C and Fig. S4). Regression analysis of total Ca2+ activity in the neuropil, astrocytic structures, and neuronal soma versus CBF responses at different stimulation frequencies (Fig. 8D) revealed significant linear dependence for the astrocytic soma (R2 = 0.74, P = 0.039) and end-feet (R2 = 0.94, P = 0.004) but not for astrocyte processes (R2 = 0.64, P = 0.064), neuropil (R2 = 0.45, P = 0.127), and neuron soma (R2 = 0.59, P = 0.081). This finding suggests that the stimulation-induced increases in CBF correlate strongly to fast Ca2+ responses in astrocyte soma and end-feet but not to astrocyte processes or neuron soma or neuropil. In addition, our results demonstrate that astrocytes are highly responsive to synaptic excitation. During a stimulus train, each stimulus evokes a short-latency Ca2+ transient in the majority of astrocytes. This finding is remarkable because it indicates that astrocytes are highly responsive to discrete synaptic events, with fast Ca2+ signals that are time- and phase-locked to the stimulus and with considerable potential impact for neurovascular coupling.

Fig. 8.

Correlation of Ca2+ signals to fEPSP and cerebral blood flow (CBF) responses. (A) Local field potential from extracellular recording during whisker stimulation. The negative deflection reflects the fEPSP whereas the subsequent positive deflection reflects the inhibitory postsynaptic potential. (B) Examples of blood flow response as recorded with laser-Doppler flowmetry. One brief peak was observed after a single stimulus whereas repeated stimuli create a long-lasting response. Values are in percentage of baseline levels. (C) The summed amplitudes of the fast Ca2+ responses versus the level of synaptic activity as indicated by the summed fEPSP amplitudes. Fast Ca2+ responses correlated linearly to the ∑fEPSP for neuropil (blue, R2 = −0.91, P = 7.6 × 10−3) and neuronal soma (green, R2 = −0.95, P = 3.1 × 10−3) and astrocytic somas (red, R2 = −0.94, P = 4.2 × 10−3) and processes (orange, R2 = −0.89, P = 9.9 × 10−3), but not for the end-feet (gray, R2 = −0.34, P = 0.1765) (n = 15 animals, Pearson’s; for number of ROIs included, see Table 1). (D) Correlation analysis of the summed Ca2+ signals versus the normalized CBF response (n = 15 animals) revealed a significant association for astrocyte soma (red, R2 = 0.74, P = 0.039) and end-feet (gray, R2 = 0.94, P = 0.004), but not for neuropil (blue, R2 = 0.46, P = 0.127), neuron soma (green, R2 = 0.59, P = 0.081), or astrocyte processes (orange, R2 = 0.64, P = 0.064) (n = 15 animals, regression analysis). All error bars are SEM.

Discussion

In this work, we showed that cortical astrocytes respond to somatosensory stimulation with intense local increases in Ca2+. This activity comprised two types of events, a fast and a slow rise in Ca2+ levels, which were clearly separable because of their distinct temporal characteristics. Slow astrocytic Ca2+ responses have been reported previously (13, 31–33). The majority of the fast, high-frequency signals could be identified only after superposition of data points recorded during a stimulation train, which might explain why fast astrocytic Ca2+ signals have so seldom been reported in vivo (9) and emphasizes the relevance of the method of analysis applied here. Our results are consistent with work in hippocampal slices (16, 17). In somatosensory cortex, previous findings suggested that only 5% of astrocyte somas had fast Ca2+ responses in vivo (9). We report that, in the whisker barrel cortex, up to 66% of astrocyte somas and 70% of processes respond with a fast Ca2+ signal and that local vasodilatation was preceded by rapid Ca2+ responses in astrocyte end-feet. We suggest that the higher prevalence of fast, short-latency Ca2+ transients in astrocytes observed in our study is the result of a high sensitivity that resulted from the combining of reordered data points, which increased the signal-to-noise ratio.

The Ca2+ responses in the neuropil appear to have been larger and more frequent than fast astrocytic Ca2+ responses as reported by others (34). This disparity raised the possibility that the fast Ca2+ responses we assigned to astrocytes were in fact fluorescence from the neuropil as has recently been proposed (8). We addressed this question in three ways. First, we showed that the fluorescence emitted from the neuropil during stimulation was below the baseline level in astrocytes and far below the levels evoked by stimulation. This result, combined with the 1.46-µm width of the axial PSF of our imaging setup, suggested a contribution from the adjacent neuropil that was far too small to account for the fast astrocytic Ca2+ responses. Second, we recorded fast Ca2+ responses in preparations in which only astrocytes were loaded with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator. The dynamic characteristics of Ca2+ responses measured in astrocytes with OGB/SR101 in the presence of changing stimulation frequencies were reproduced with Rhod2. The quantitative differences in signals between OGB and Rhod2 may be ascribed to the difference in dissociation constants for the two dyes and the higher accumulation of Rhod2 in mitochondria (28). Third, the fast Ca2+ response in the neuropil preceded the Ca2+ responses in astrocytes and other structures by 20 ms. This dissociation in time further supports that the fast Ca2+ signals are separate events in astrocytes and neuropil. It has been suggested that analysis of astrocytic Ca2+ activity is problematic due to the suspicion that astrocytes may contain neuronal processes (8). This notion is based on descriptions of how astrocyte processes fill out a volume around neuronal somas and dendrites (35, 36). However, the astrocyte somas are dense and largely filled by organelles, including the cell nucleus (27, 37), and have not been shown to be pierced by neuronal subcellular elements. Therefore, the fast Ca2+ signals we observed in astrocytes, in particular the somas, are not explained by a partial volume effect produced by contamination from neuronal processes.

The evoked fast Ca2+ responses were more consistent in neuropil and neuron somas than in astrocytic structures, and the neuropil responses were faster. We consider this pattern to reflect the time it takes from the start of the synaptic input to the opening of Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane as well as internal stores. The size of the fast Ca2+ responses in neuronal soma, neuropil, and astrocyte soma and processes correlated with the amplitude of the fEPSP; thus, the Ca2+ changes might reflect the level of synaptic excitation. Astrocytes are known to be positioned close to synapses, forming what has been termed the tripartite synapse (38). The fast astrocytic Ca2+ response was inhibited by blocking glutamate AMPA receptors. This sensitivity suggests that full activation of astrocytes occurs downstream from AMPA-mediated recruitment of cortical neurons by the afferent synaptic input from cortical layer IV, whereas the mGluR sensitivity of the response points to the mGluR-mediated signaling pathway for astrocyte activation.

Ca2+ levels in astrocytic somas respond to glutamate spillover from the synaptic cleft (1). mGluR5a activation leads to increased cytosolic Ca2+ by IP3-mediated release from endoplasmic reticulum (32, 33) and could be the pathway from stimulation to rapid Ca2+ responses in astrocytes. The presence of mGluR5a in astrocytes in adult mouse cortex is debated (8, 39), and we cannot exclude that the effect of the mGluR5 receptor antagonist on Ca2+ signals in our experiments is indirect, i.e., via an effect of synaptic transmission. Alternatively, one might speculate that ATP release from interneurons may trigger the fast astrocytic Ca2+ (40, 41). Nevertheless, the correlation between the fast Ca2+ responses in astrocytes and the amplitude of the fEPSPs supports the notion that Ca2+ responses are evoked by synaptic activity. The average decay time for the fast responses was 49 ms in our experiments (tau, Fig. 7), much faster than the latency of slow Ca2+ responses (33). The latency and duration of the fast Ca2+ responses that we recorded in astrocytes in the somatosensory cortex of anesthetized mice in vivo are compatible with their being evoked by single stimuli, similar to the responses in the cerebellum of awake mice (42) and in hippocampal slices (17).

This work combined electrophysiological and hemodynamic measures with 2-photon microscopy of Ca2+ transients to study neurovascular coupling. By sampling fast astrocytic Ca2+ signals, we demonstrated the high occurrence of these local signals and established a clear linear relationship between the Ca2+ transients in astrocyte soma and end-feet and the hemodynamic response. This association was further supported by the observation of fast astrocytic Ca2+ responses in end-feet before dilation of an adjacent vessel. The rise in astrocytic Ca2+ reported here is similar to what has been reported for slice preparations associated with local vasodilatation (14, 43). We suggest that stimulation-induced Ca2+ increase may provide the rapid neurovascular coupling needed to adapt metabolic activity to fluctuations in neuronal network activity. We cannot exclude that neuronal activity modulates the CBF responses as well although we did not observe a statistically significant correlation between the fast neuronal Ca2+ responses and the size of the blood flow response. The neuronal Ca2+ responses correlated to the LFP amplitude. Interneuron activity is only weakly reflected in extracellular LFPs in the cortex because of their functional anatomy (44) but interneurons were included in the neuron soma and the neuropil categories when evaluating Ca2+ signals. The lack of linear correlation between CBF responses and the summed fast Ca2+ responses reflects the divergence of these signals at higher stimulation frequencies; although the summed neuronal Ca2+ responses increased continually with stimulation frequencies, the CBF responses saturated at 2–3 Hz.

Regardless, by providing direct evidence for fast Ca2+ responses, our study resolves the controversy over whether they appear rapid enough in astrocytes to contribute to neurovascular coupling. We suggest that fast and slow astrocytic Ca2+ signals may contribute to different phases of the CBF response (45), as follows: Fast Ca2+ signals may initiate the CBF response, and the slower and longer-lasting astrocytic Ca2+ elevations could contribute to the sustained hemodynamic response. Our work points to an immediate interaction between neurons and astrocytes and a key role for fast astrocytic Ca2+ responses as a basic mechanism in neurovascular coupling.

Materials and Methods

Animal Handling.

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Danish National Ethics Committee according to the guidelines set forth in the European Council’s Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes. Male white Naval Medical Research Institute mice (8 week old, Crl:NMRI) were surgically prepared for experiments as described previously (46). A craniotomy was drilled with a diameter of ∼4 mm with the center 0.5 mm behind and 3 mm to the right of the bregma over the motor–sensory barrel cortex region. During experiments, animals were anesthetized with alpha-chloralose (i.v.). A total of 32 animals were used in the 2-photon experiments. An additional 14 animals were used to study blood flow in a separate experimental setup.

Stimulation.

The mouse sensory barrel cortex was activated by stimulation of the contralateral ramus infraorbitalis of the trigeminal nerve using a set of custom-made bipolar electrodes inserted percutaneously. The cathode was positioned corresponding to the hiatus infraorbitalis (IO), and the anode was inserted into the masticatory muscles (21). Thalamocortical IO stimulation was performed at an intensity of 1.5 mA (ISO-flex; A.M.P.I.) and lasting 1 ms, in trains of 15–45 s at 0.5–5 Hz.

Electrophysiology.

A single-barreled glass microelectrode filled with 2 mol/L saline (impedance, 2–3 MΩ; tip, 2 µm) was inserted into the whisker cortex layer II/III for recordings of the extracellular local field potentials (LFP). An Ag/AgCl electrode inserted in the neck muscles served as ground. The mV negativity in LFP recordings was considered as the fEPSP. The signal was amplified using a differential amplifier (gain 10×, bandwidth 0.1–10,000 Hz; DP-311; Warner Instruments) first, followed by additional amplification using CyberAmp 380 (gain 100×, bandwidth 0.1–5,000 Hz; Axon Instruments), and digitally sampled using the 1401mkII interface (Cambridge Electronic Design) connected to Spike2.5 software (Cambridge Electronic Design) running at a sampling rate of 20 kHz.

Cortical Blood Flow Measurements.

Hemodynamic responses were measured by intrinsic optical signals or monitored using laser-Doppler flowmetry (LDF).

Intrinsic optical signaling.

Intrinsic optical signals were recorded on a Leica microscope at 4× magnification and including the entire preparation in the field of view. The light source consisted of LEDs with green light filters to ensure imaging of changes in blood volume (19). A fast-capturing camera (QuantEM 512SC) sampled 100 images/3.5 s before and during 15 s of 5 Hz stimulation. The difference in absorption due to shifts in oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin concentrations was calculated (47).

Laser-Doppler flowmetry.

A flexible probe (MT B500-0, 0–500 µm fiber separation; Perimed) was glued to the skull next to the craniotomy and angled to measure within the craniotomy. In experiments outside the microscope, another probe (415-264, 140 µm fiber separation; Perimed) was placed above the microelectrode that recorded electrophysiological variables (PeriFlux 4001 Master; wavelength 780 nm; Perimed). The LDF signal was smoothed with a time constant of 0.2 s, sampled at 10 Hz, A/D converted, and then digitally recorded and smoothed again (time constant = 1 s) using the Spike2 software. The LDF method does not measure CBF in absolute terms; however, it is valid for determining relative changes in CBF during moderate increases in flow (48). Evoked CBF increases were expressed in percentage of baseline. No significant changes in the CBF baseline were observed during the experiments.

Two-Photon Imaging.

Ca2+ imaging was performed using a commercial 2-photon microscope (SP5 multiphoton/confocal Laser Scanning Microscope; Leica), a MaiTai HP Ti:Sapphire laser (Millennia Pro; Spectra Physics), and a 20 × 1.0 N.A. water-immersion objective (Leica). Tissue 100–120 um below surface was excited with an 800-nm wavelength laser, and the emitted light was split to red and green light. The field of view was scanned at 12 Hz in 75- to 90-s periods. The tissue was at no time exposed to above 20 mW, and no signs of phototoxicity were observed.

Dye Loading.

In 2-photon experiments, we used two types of rhodamine-based dye to identify the astrocytes: Rhod2 (rhod-2, AM; 0.8 mM diluted in aCSF; Invitrogen, Molecular Probes) and SR101 (sulforhodamine 101; 1 mM diluted in aCSF; Sigma-Aldrich). Both dyes were surface-loaded before agarose application. Oregon Green Bapta-1/AM (OGB-1/AM; 0.8 mM diluted in aCSF; Invitrogen, Molecular Probes) in dimethyl sulfoxide plus 20% (wt/vol) SDS Pluronic F-127 (BASF Global) was bulk-loaded in the cerebral cortex using extracellular microinjection (4–6 psi, 4 s; Pneumatic Pump; World Precision Instruments). In some experiments, 10% (wt/vol) SDS TRITC-dex (tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-Dextran; Sigma-Aldrich) was administered into the venus femoralis to label the blood plasma.

Image Analysis.

Stimulation of the whisker pad increased fluorescence emitted from the calcium indicator (Rhod2 or OGB), reflecting Ca2+ activity in the tissue. The labeling pattern of the SR101 dye was used to select regions of interest (ROIs) as either astrocytic or neuronal. The fluorescence changes were averaged within ROIs. Analytical software was custom-made using Matlab and a scientific Python toolchain: SciPy (www.scipy.org) and Matplotlib (www.matplotlib.org).

Isolation of slow Ca2+ responses.

Ca2+ signals from ROIs were filtered to separate the high- and low-frequency activity during stimulation. They were then normalized to percentages of the level during the baseline period and smoothed by nondecimated discrete wavelet transform, discarding all details at the sixth level of decomposition and keeping only the last smoothed approximation of the signal. Given the sampling interval, the approximation was roughly equivalent to smoothing with a Gaussian low-pass filter with σ = 3 s. After smoothing, the positions of the local extrema of the smoothed signal and its first derivative were found. The onset of the response (start time) was calculated as the position of the maximum of the first derivative (fastest rate of change) occurring before the position of the main peak in the smoothed signal, but after the stimulus (Fig. 2B, red triangle). The response was considered significant if the main peak of the smoothed signal exceeded 0.85 SDs of the analyzed signal (SD calculated during the baseline period). The threshold was low because we use smoothed signals for analysis and most of the noise was fast-changing so that it was effectively removed when smoothing. Therefore, we could use a low threshold value because we defined threshold relative to SD from the nonsmoothed ΔF/F0 signals.

Fast, single Ca2+ signal interpolation.

Averaged fluorescence signals from ROIs were normalized based on the fluorescence changes in the baseline period to estimate the Ca2+ changes in an arbitrary scale. The signals were calculated either as a percentage of the baseline level (ΔF/F0) or in SDs of the activity during the baseline period (ΔFSD = ΔF-F0/SD0). The latter was used to assess the level of statistical significance by which the value deviated from the nonstimulated Ca2+ activity. All pixels within the ROI were included in the signal. The samples taken after the different stimulation in the stimulation train were superimposed to form a cloud of data points after a fictive single stimulation and interpolated to provide an estimate of the true Ca2+ response (Movie S2).

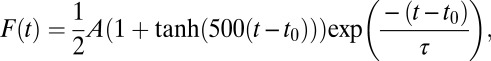

The fast Ca2+ signals were fitted by a pulse function with instantaneous rising front and exponentially decaying tail:

Amplitude A, onset time T0, and characteristic decay time τ were obtained from the least squares fit of this function to the cloud of points and used to characterize transient fluorescent responses.

A recent work (49) reported two time constants in the decay of Ca2+ transients: around 56 ms and around 780 ms for the fast and slow components, respectively. With our stimulation rates, the slower component (of the order of seconds) could only have effect in fitting of the observed fluorescence kinetics for the 0.5–1 Hz stimulations. Therefore, the fast Ca2+ transients for the 2- to 5-Hz stimulations were fitted with a pulse function with almost instantaneous rise and a single exponential decay:

|

parametrized with the peak amplitude A, peak time t0 and decay time constant τ.

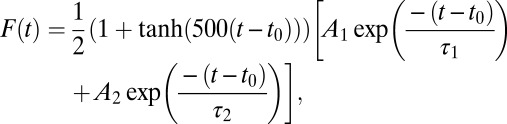

For the 0.5- to 1-Hz stimulations, we used a pulse function with a double-exponential decay:

|

parametrized with two nonnegative peak amplitudes A1 and A2, peak time t0, and decay time constants τ1 and τ2 . In both cases, the parameters were obtained from the least squares fit of the cloud of points and used to characterize transient fluorescent responses. In the case of double-exponential fits, only the faster component was used.

Whole picture analysis of fast Ca2+ responses.

TIFF images of the red/green fluorescence were normalized based on the baseline intensity levels as either percentage or FSD. They were rearranged using the stimulation time as time lock, in the same way as the data averaged over ROIs (Fig. S2). Thus, the fast Ca2+ signals could be visualized on a single-pixel scale by linear interpolation over data points in the same pixel from image to image. Either the size of the Ca2+ response was calculated in percentage of baseline (ΔF/F0) (Figs. 3 and 5) or in SD of baseline (FSD) (Figs. 4 and 6), or the fast Ca2+ responses were classified as astrocytic or nonastrocytic (Fig. 7). In Fig. 7, only pixels with levels >2 SD of baseline levels were presented because they were considered to represent significant Ca2+ responses. To define areas as astrocytic, the SD of the color levels of the entire image in the red channel (SR101) was used. Pixels were defined as astrocytic if their intensity was >2 SD.

Postsampling line analysis of vessel diameter.

The green channel was used because the bulk-loaded OGB dye outlined the vessels within the field of view. A region sheathed by astrocyte end-feet was chosen based on SR101 staining, and a transverse line was selected. A series of XY images were taken before, under, and after a stimulation train and were averaged over time with a 1-s-wide moving window. All pixels belonging to the line were extrapolated from the time series as an XT (transverse line × time) image. Pixels corresponding to the vessel were taken as those whose intensity was ≥85% of the average pixel intensity of the whole XT image. For any time point, the width of the vessel was then calculated as the number of these pixels at the time point in question. A dilatation was considered to be significant when five or more time points showed a vessel diameter more than 2 SD broader than before stimulation. All analysis was done with a custom-made program written in Matlab.

Z-Axis Influence on Fluorescence.

Estimation of point-spread function in the z axis.

The point-spread function of our system was estimated by scanning of 1-µm fluorescent microbeads. The center of the centroid and the difference between actual and perceived diameter were used to calculate sigma, as described (24, 25) (Fig. 5E).

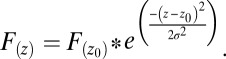

Z axis distribution of neuropil fluorescence.

The influence of fluorescence from one point to the layer above and below as a result of point spread is Gaussian distributed:

|

F(z0) is peak fluorescence intensity among given points, F(z) is the fluorescence at another point, and z − z0 is the distance between the two points. The axial distribution width is then σ and was found to be 1.46 µm in our system. The formula was used to find the level of fluorescence contributed by overlying and underlying neuropil to the centers of several astrocytes (Fig. 5 F and G).

Drug Application.

CNQX (6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium salt; Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as a 2-mM solution, with the pH adjusted to a physiological value (7.4) with NaOH and HCl, and used in three experiments. It was dissolved in aCSF and applied by placing drops of the dissolved compound on the agarose covering the cortex. MPEP [6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl) pyridine, hydrochloride; Sigma-Aldrich] was administered i.v. (0.5 µg in a 200-µl bolus), reaching an estimated plasma concentration of 0.7 µM. Five animals were included in the MPEP experiments.

Statistical Analysis.

The number of ROIs included in the study is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of ROIs included in the study

| No. of animals | Length of stimulation period, s | Neuron soma ROIs | Neuropil ROIs | Astrocyte soma ROIs | Astrocyte processes ROIs | Astrocyte end feet ROIs |

| 32 | 45 or 15 | 485 | 115 | 151 | 110 | 125 |

| 15 | 15 | 195 | 60 | 69 | 54 | 27 |

The drug effects of CNQX and MPEP and a comparison of the size and timing of fast Ca2+ signals in different cellular compartments were analyzed using three-way analysis of variance [ANOVA; R, R Development Core Team (2010); R Foundation for Statistical Computing], followed by a paired t test for significance at specific time points. The significance level was set at a two-tailed α of 0.05. In some cases, data were log-transformed before analysis to obtain a normal distribution.

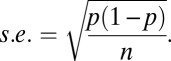

Mean fEPSPs were correlated to mean peak amplitudes of Ca2+ transients obtained during the same stimulation train in the same animal (Extreme; OriginPro 8.1). CBF responses were calculated as area under the curve (AUC) of the CBF signals using Matlab and normalized to the preceding 30-s baseline. Mean CBF responses were then correlated to mean peak amplitudes of Ca2+ transients obtained with the same experimental protocol in different preparations using 2-photon imaging (Extreme; OriginPro 8.1). The different points in Fig. 8 represent different stimulation frequencies.

Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. When the mean of proportions is presented, the error bars are in SE of proportions:

|

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor David Attwell (University College London) and Professor Jørn Hounsgaard (University of Copenhagen) for reading the manuscript and Micael Lønstrup for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, the NOVO-Nordisk Foundation, the Danish Medical Research Council, the NORDEA Foundation for the Center for Healthy Aging, and Fondation Leducq.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1310065110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Attwell D, et al. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468(7321):232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iadecola C, Nedergaard M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(11):1369–1376. doi: 10.1038/nn2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koehler RC, Roman RJ, Harder DR. Astrocytes and the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(3):160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauritzen M. Reading vascular changes in brain imaging: Is dendritic calcium the key? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(1):77–85. doi: 10.1038/nrn1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nedergaard M, Rodríguez JJ, Verkhratsky A. Glial calcium and diseases of the nervous system. Cell Calcium. 2010;47(2):140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCaslin AF, Chen BR, Radosevich AJ, Cauli B, Hillman EM. In vivo 3D morphology of astrocyte-vasculature interactions in the somatosensory cortex: Implications for neurovascular coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(3):795–806. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon GR, Howarth C, MacVicar BA. Bidirectional control of arteriole diameter by astrocytes. Exp Physiol. 2011;96(4):393–399. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.053132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nizar K, et al. In vivo stimulus-induced vasodilation occurs without IP3 receptor activation and may precede astrocytic calcium increase. J Neurosci. 2013;33(19):8411–8422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3285-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winship IR, Plaa N, Murphy TH. Rapid astrocyte calcium signals correlate with neuronal activity and onset of the hemodynamic response in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27(23):6268–6272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4801-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petzold GC, Albeanu DF, Sato TF, Murthy VN. Coupling of neural activity to blood flow in olfactory glomeruli is mediated by astrocytic pathways. Neuron. 2008;58(6):897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Achour S, Pont-Lezica L, Béchade C, Pascual O. Is astrocyte calcium signaling relevant for synaptic plasticity? Neuron Glia Biol. 2010;6(3):147–155. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X10000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schummers J, Yu H, Sur M. Tuned responses of astrocytes and their influence on hemodynamic signals in the visual cortex. Science. 2008;320(5883):1638–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1156120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, et al. Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling evoked by sensory stimulation in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(6):816–823. doi: 10.1038/nn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon GR, Choi HB, Rungta RL, Ellis-Davies GC, MacVicar BA. Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature. 2008;456(7223):745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature07525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zonta M, et al. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Castro MA, et al. Local Ca2+ detection and modulation of synaptic release by astrocytes. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(10):1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panatier A, et al. Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell. 2011;146(5):785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn AK, et al. Simultaneous imaging of total cerebral hemoglobin concentration, oxygenation, and blood flow during functional activation. Opt Lett. 2003;28(1):28–30. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frostig RD, Lieke EE, Ts’o DY, Grinvald A. Cortical functional architecture and local coupling between neuronal activity and the microcirculation revealed by in vivo high-resolution optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(16):6082–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devor A, et al. Frontiers in optical imaging of cerebral blood flow and metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(7):1259–1276. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norup Nielsen A, Lauritzen M. Coupling and uncoupling of activity-dependent increases of neuronal activity and blood flow in rat somatosensory cortex. J Physiol. 2001;533(Pt 3):773–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stosiek C, Garaschuk O, Holthoff K, Konnerth A. In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Kerr JN, Helmchen F. Sulforhodamine 101 as a specific marker of astroglia in the neocortex in vivo. Nat Methods. 2004;1(1):31–37. doi: 10.1038/nmeth706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong CY, Koenig K, So P. Characterizing point spread functions of two-photon fluorescence microscopy in turbid medium. J Biomed Opt. 2003;8(3):450–459. doi: 10.1117/1.1578644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drew PJ, et al. Chronic optical access through a polished and reinforced thinned skull. Nat Methods. 2010;7(12):981–984. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantevari S, Gordon GR, MacVicar BA, Ellis-Davies GC. A practical guide to the synthesis and use of membrane-permeant acetoxymethyl esters of caged inositol polyphosphates. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(3):327–337. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takano T, et al. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(2):260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paredes RM, Etzler JC, Watts LT, Zheng W, Lechleiter JD. Chemical calcium indicators. Methods. 2008;46(3):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaigneau E, et al. The relationship between blood flow and neuronal activity in the rodent olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2007;27(24):6452–6460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3141-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathiesen C, et al. Activity-dependent increases in local oxygen consumption correlate with postsynaptic currents in the mouse cerebellum in vivo. J Neurosci. 2011;31(50):18327–18337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4526-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz K, et al. Simultaneous BOLD fMRI and fiber-optic calcium recording in rat neocortex. Nat Methods. 2012;9(6):597–602. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thrane AS, et al. General anesthesia selectively disrupts astrocyte calcium signaling in the awake mouse cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(46):18974–18979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209448109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong X, Shigetomi E, Looger LL, Khakh BS. Genetically encoded calcium indicators and astrocyte calcium microdomains. Neuroscientist. 2013;19(3):274–291. doi: 10.1177/1073858412468794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stutzmann GE, LaFerla FM, Parker I. Ca2+ signaling in mouse cortical neurons studied by two-photon imaging and photoreleased inositol triphosphate. J Neurosci. 2003;23(3):758–765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00758.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halassa MM, Fellin T, Takano H, Dong JH, Haydon PG. Synaptic islands defined by the territory of a single astrocyte. J Neurosci. 2007;27(24):6473–6477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1419-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves AMB, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS. Bulk loading of calcium indicator dyes to study astrocyte physiology: Key limitations and improvements using morphological maps. J Neurosci. 2011;31(25):9353–9358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0127-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovatt D, et al. The transcriptome and metabolic gene signature of protoplasmic astrocytes in the adult murine cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27(45):12255–12266. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3404-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nedergaard M, Verkhratsky A. Artifact versus reality—how astrocytes contribute to synaptic events. Glia. 2012;60(7):1013–1023. doi: 10.1002/glia.22288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun W, et al. Glutamate-dependent neuroglial calcium signaling differs between young and adult brain. Science. 2013;339(6116):197–200. doi: 10.1126/science.1226740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doengi M, Deitmer JW, Lohr C. New evidence for purinergic signaling in the olfactory bulb: A2A and P2Y1 receptors mediate intracellular calcium release in astrocytes. FASEB J. 2008;22(7):2368–2378. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-101782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, Liu QS, Nedergaard M. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci. 2003;23(27):9254–9262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nimmerjahn A, Mukamel EA, Schnitzer MJ. Motor behavior activates Bergmann glial networks. Neuron. 2009;62(3):400–412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn KM, Hill-Eubanks DC, Liedtke WB, Nelson MT. TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytic endfeet and amplify neurovascular coupling responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(15):6157–6162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216514110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enager P, et al. Pathway-specific variations in neurovascular and neurometabolic coupling in rat primary somatosensory cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(5):976–986. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen BR, Bouchard MB, McCaslin AF, Burgess SA, Hillman EM. High-speed vascular dynamics of the hemodynamic response. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathiesen C, Brazhe A, Thomsen K, Lauritzen M. Spontaneous calcium waves in Bergman glia increase with age and hypoxia and may reduce tissue oxygen. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(2):161–169. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison TC, Sigler A, Murphy TH. Simple and cost-effective hardware and software for functional brain mapping using intrinsic optical signal imaging. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;182(2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fabricius M, Lauritzen M. Laser-Doppler evaluation of rat brain microcirculation: Comparison with the [14C]-iodoantipyrine method suggests discordance during cerebral blood flow increases. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(1):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grewe BF, Langer D, Kasper H, Kampa BM, Helmchen F. High-speed in vivo calcium imaging reveals neuronal network activity with near-millisecond precision. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):399–405. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.