Abstract

The behavioral inhibition (BIS) and behavioral approach systems (BAS) are thought to influence sensitivity to reinforcement and punishment, making them useful for predicting mood-related drinking outcomes. This study provided the first examination of BIS and BAS as moderators of longitudinal within-person associations between mood and alcohol-related consequences in college student drinkers. Participants (N=637) at two public U.S. universities completed up to 14 online surveys over the first three years of college assessing past-month general positive and negative mood, as well as past-month alcohol use and consequences. BIS and BAS were assessed at baseline. Using multilevel regression, we found that BIS and BAS moderated the within-person associations between negative mood and alcohol consequences. For students high on BIS only, high on BAS only, or high on both BIS and BAS, within-person increases in negative mood were associated with greater alcohol consequences in the first year of college. However, these negative mood-alcohol consequence associations diminished over time for students high on BIS and low on BAS, but remained strong for students high on both BIS and BAS. Within-person associations between positive mood and alcohol consequences changed from slightly positive to slightly negative over time, but were not moderated by BIS or BAS. Findings suggest that BIS and BAS impact the within-person association between general changes in negative mood and negative alcohol consequences, working jointly to maintain this relationship over time.

Keywords: behavioral approach system, behavioral inhibition system, mood, alcohol, alcohol consequences, longitudinal

1. Introduction

Alcohol use is prevalent among college students and is often associated with negative physical, social, and academic consequences (see Perkins, 2002; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). Much research has been devoted to understanding factors that contribute to problematic drinking (i.e., alcohol use that results in negative consequences) in this population. A great deal of this research has examined the link between mood and drinking behavior, as motivational models of alcohol use (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1988) suggest that drinking to regulate mood – especially negative mood – is strongly associated with negative alcohol consequences (Cooper et al., 1995; Merrill & Read, 2010).

Though mood-related alchol use is known to be important to the etiology of problematic drinking in college students (e.g., Cooper et al., 1995; O'Hare, 1997; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003), the literature on both the direction and strength of the relations between mood and problematic drinking has yielded mixed findings. For example, college students experiencing negative mood (e.g., anxiety, depression) may misuse alcohol to alleviate unpleasant emotions (Martens et al., 2008; Mohr et al., 2005; Simons, Gaher, Oliver, Bush, & Palmer, 2005). Yet, negative mood (e.g., social anxiety) may also lead students to avoid social settings in which risky drinking typically occurs (Gilles, Turk, & Fresco, 2006; Ham & Hope, 2005; Rankin & Maggs, 2006). In addition, high levels of positive mood can lead to reckless drinking motivated by a desire to further enhance pleasure and enjoyment (i.e., celebratory drinking, Mohr et al., 2005; Simons, Dvorak, Batien, & Wray, 2010; Simons et al., 2005). But, low positive mood may drink to increase arousal and deal with boredom (Wills, Sandy, Shinar, & Yaeger, 1999). It is clear from the complexity of this literature that the role that mood plays in drinking behavior has not been fully resolved. Thus, research has been devoted to clarifying these associations in college students, including studies of within-person associations as well as potential moderators.

1.1. Within-Person Associations between Mood and Alcohol Consequences

Much of the research on the relationship between mood and negative alcohol outcomes has focused on between-person associations. In these studies, individual differences are examined to determine whether problematic drinking is greater among individuals who are elevated on particular mood states at a given point in time. However, this approach has been criticized for ignoring within-person changes in mood and corresponding changes in alcohol consequences (see Armeli, Todd, & Mohr, 2005; Rankin & Maggs, 2006). Theoretical accounts of mood-related drinking suggest that changes in mood over time should be correlated with increases or decreases in the risk for problematic outcomes of drinking (Cooper et al., 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1988). Thus, within-person analyses are needed to address the question of whether individuals experience more negative alcohol consequences when they experience changes in mood.

Accordingly, some recent research has examined within-person associations between mood and drinking behavior in college students (e.g., Armeli, Tennen, Affleck, & Kranzler, 2000; Hussong, Hicks, Levy, & Curran, 2001; Mohr et al., 2005; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004; Simons et al., 2005). These studies generally involve repeated assessments of mood and alcohol involvement to examine whether within-person changes in mood are associated with corresponding changes in alcohol use for the same individuals. An important finding from these studies is that the associations between mood and drinking behavior may differ depending on whether a between-person or within-person level of analysis is used (Park et al., 2004; Rankin & Maggs, 2006).

However, previous studies have tended to focus on alcohol consumption levels, and there have been few examinations of within-person associations between mood and negative alcohol consequences. More research on these associations is important, given that mood-related alcohol use is major risk factor for alcohol-related problems (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; Martens et al., 2008). Indeed, even after controlling for level of alcohol consumption, drinking that is linked to negative moods is associated with greater negative alcohol consequences (Cooper et al., 1995; Merrill & Read, 2010). Perhaps drinkers who use alcohol to regulate their mood tend to engage in riskier drinking practices with a high potential for negative outcomes (e.g., drinking the night before an exam to cope with stress). This could result in within-person associations between mood changes and negative alcohol consequences that are not entirely a function of changes in consumption levels.

1.2. The Importance of Timing: Drinking Over the College Years

Within-person associations between mood and negative alcohol consequences could play out over different time periods. For example, moment-to-moment changes in mood state may lead to immediate alcohol use and proximal negative consequences, while broader shifts in global mood state could result in more chronic changes in the risk for alcohol-related consequences as mood-related drinking consequences accumulate over longer time frames. Most studies of within-person associations have focused on daily changes in mood and alcohol use. Yet, daily alcohol use is relatively rare in college, where the majority of students report drinking less than once per week (e.g., Del Boca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004; Rankin & Maggs, 2006). Moreover, mood not only fluctuates from moment-to-moment, but global fluctuations in mood occur over monthly and yearly time intervals (Murray, Allen, & Trinder, 2001; Wills et al., 1999). Importantly, there is some evidence from the developmental literature that within-person fluctuations in chronic mood states are related to changes in substance use among adolescents (Wills et al., 1999). However, with only a few exceptions, most of the research on the relationship between chronic mood states and alcohol use has focused on between-person changes on global mood measures over time. Currently, there is a gap in the literature between the short-term, daily studies of within-person mood-drinking associations, and the longer-term, between-person studies of mood-drinking relationships. Accordingly, in this study we provide an examination of within-person associations between more chronic changes in mood over a period of several years and corresponding changes in negative alcohol consequences.

In addition, research shows that academic level or year in college has an influence over student’s alcohol involvement, with heavy drinking and alcohol problems tending to decline over the college years (Baer, Kivlahan, Blume, McKnight, & Marlatt, 2001; Harford, Wechsler, & Seibring, 2002). Further, there is some evidence that the relationship between emotional distress and alcohol consequences may change during the course of college (e.g., Jackson & Sher, 2003). The transition into college is a time of heightened instability and emotional stress for many students as they are adjusting to a new environment and new responsibilities (Arnett, 2005). Thus, the association between negative mood and problematic drinking may be more likely for some students early in college (see also Stewart, Zeitlin, & Samoluk, 1996) but may change in subsequent years1. Given that most of the studies in this area have used brief assessment intervals (i.e., daily, weekly) over brief time periods (e.g., a month or two), little is currently known about how these associations change over the college years. Also, drinking behavior varies substantially over the course of the academic year and shows strong seasonal variation (Del Boca et al., 2004). So, longitudinal examinations of within-person associations between mood and alcohol consequences must also account for such variations. Accordingly, the present study assessed mood and alcohol consequences at various seasonal time points (early fall, late fall, early spring, late spring).

1.3. The Moderating Role of Behavioral Approach and Inhibition Systems

Because alcohol use can have both rewarding (e.g., improved mood) and aversive (e.g., hangover) outcomes, mood-related drinking may depend partly on individual differences in sensitivity to reinforcement and punishment (Cox & Klinger, 1988). Among the most relevant traits to this process are the Behavioral Approach (BAS) and Behavioral Inhibition Systems (BIS), which are biologically-based neural systems underlying trait sensitivity to reinforcement and punishment. As BAS and BIS are generally stable over time (Carver & White, 1994; Kasch, Rottenberg, Arnow, & Gotlib, 2002), they are useful prospective predictors of alcohol use (Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012).

According to Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST), individuals with a strong BAS are thought to be sensitive to reinforcement and are motivated to approach rewards (Corr, 2008; Gray, 1987). A strong BAS is a risk factor for problematic drinking among college students (e.g., Hundt, Kimbrel, Mitchell, & Nelson-Gray, 2008; O'Connor & Colder, 2005) and is prospectively linked to beliefs that alcohol enhances positive mood and reduces negative mood (Wardell, Read, Colder, & Merrill, 2012). In contrast, individuals with a strong BIS are thought to be sensitive to punishment and motivated to avoid risk (e.g., Corr, 2008). RST contends that BIS inhibits approach behavior and promotes risk-assessment to determine whether approach or avoidance goals should be pursued (Corr, 2008; Gray & McNaughton, 2000). Yet, the role of BIS in drinking behavior is not entirely clear. Some research suggests that individuals with a strong BIS are less likely to engage in problematic drinking, presumably because the aversive outcomes are more salient to them (Pardo, Aguilar, Molinuevo, & Torrubia, 2007). Other research points to BIS as a risk factor for problematic drinking, as individuals with a strong BIS may be prone to experience negative moods and therefore may engage in risky behaviors as a mood regulation strategy (Voigt et al., 2009).

A major tenant of RST – the Joint Subsystems Hypothesis – states that BIS and BAS have interactive effects on behavior, such that the influence of one system is moderated by the strength of the other system (Corr, 2002). The association between BIS and problematic alcohol use may be moderated by BAS, such that problematic drinking is greatest among individuals high on both BIS and BAS (see Wardell, O'Connor, Read, & Colder, 2011). Drawing from RST, one might speculate that a strong BIS places individuals at risk for drinking in response to negative emotions, but a strong BAS also is needed to increase the salience of the rewarding, tension reducing effects of alcohol and motivate drinking behavior.

There is evidence that BIS and BAS prospectively predict drinking behavior over long time frames (e.g., a full year; Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012). This is consistent with RST, as the sensitivity to reinforcement and punishment that arise from BIS and BAS make it likely that these systems will have an influence on changes in behavior over time as a result of experience (see Corr, 2008). Thus, it follows that BIS and BAS could either strengthen or weaken associations between mood and problematic drinking over time, as they could influence the salience of the different outcomes of this behavior and impact drinking motivation. This process may unfold gradually over long time frames, as individuals accumulate more experiences with mood-related drinking outcomes. Applying concepts from RST, one might speculate that individuals with a strong BAS may be more sensitive to the desirable effects that alcohol has on mood, which could reinforce mood-related drinking and maintain this behavior over time. Individuals with a strong BIS, however, may be sensitive to the negative outcomes of drinking, leading to a decrease in mood-related drinking over time, unless they also have a strong BAS to shift the focus to the rewarding tension reducing outcomes of drinking alcohol.

1.4. The Present Study

This study examined BIS and BAS as moderators of within-person associations between global past-month mood and problematic drinking over a three-year period in a sample of college student drinkers. We predicted that BIS and BAS would interact with one another to influence the within-person association between negative mood and negative alcohol consequences. Specifically, we hypothesized that (1) individuals high on either BIS or BAS (or both) would show positive within-person associations between negative mood and alcohol consequences early in college, whereas those low on both BIS and BAS would not show these associations; and (2) individuals high on BAS, regardless of BIS level, would show continued within-person associations between negative mood and alcohol consequence throughout the three years of the study, whereas this association would diminish over the course of the study for those high on BIS but low on BAS. We also explored the interactive role of BIS and BAS in the link between within-person changes in positive mood and problematic drinking but did not forward specific hypotheses.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 637 (66% female) college student drinkers who completed a baseline assessment in September of their first college semester (T1) and were followed for 3 years. Average age at T1 was 18.11 (SD=0.44). Seventy-nine percent self-identified as Non-Hispanic Caucasian (n=502), 8% as Asian (n=51), 6% as Black (n=38), 4% as Hispanic/Latino (n=22), 3% as multiracial (n=19), and less than 1% (n=2) as other. Three participants did not report ethnicity. Living arrangements were highly stable within each academic year. In year 1, the majority of students reported living on campus (approximately 80% at each time point). Across year 2, approximately 50% of students reported living on campus, 25% off campus, and 25% at home with family. Across year 3, roughly 25% of students lived on campus, 50% off campus, and 25% at home with family.

2.2 Procedure

All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating sites. Participants were drawn from larger study investigating trauma and substance use (Read et al., 2012). Matriculating students (ages 18–24) at two mid-sized public U.S. universities (one in the northeast and one in the southeast) were recruited in the summer prior to matriculation to participate in a longitudinal, web-based study. A screening survey was administered to determine eligibility for the study. The response rate for this initial screen was 58% (3391/5885), consistent with other studies using similar methods (Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004; Neighbors, Geisner, & Lee, 2008). From this sample, those meeting traumatic stress criteria (i.e., at least one traumatic event and three or more symptoms of PTSD) and an equal number of randomly selected control participants (i.e., those who were below this threshold) were selected to take part in the longitudinal study (N=1234). Of these, a total of 1002 (81% response rate) participants completed a baseline survey (T1) and were targeted for longitudinal follow-up. For the present study, we were interested in examining how within-person mood processes among drinkers were associated with alcohol-related consequences, and thus only participants who reported past month alcohol use at T1 (n=637) were included. Participants completed 5 subsequent assessments in the same academic year (October, November, December, February, and April). Participants then were assessed 4 times annually (September, December, February, April) over the next 2 years.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Demographics questionnaire

At T1, participants reported on a range of demographic characteristics, including gender, age, ethnicity, and residential status.

2.3.2 BIS and BAS

Carver & White’s (1994) BIS/BAS scales were used to assess the BIS (7 items) and three sub-components of the BAS: Drive (4 items), Fun-Seeking (4 items) and Reward Responsiveness (5 items). Participants rated items on a 4-point scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). A mean score was derived for the BIS scale and scores on the BAS sub-factors were averaged to create a mean BAS score (Carver & White, 1994). We observed adequate internal consistency for the BIS (alpha = .77) and BAS (alpha = .82) scales in this sample. BAS and BIS were assessed at Time 1.

2.3.3. Positive and Negative Mood

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) assessed mood by asking participants to rate the degree to which they have experienced 10 positive (e.g., excited, enthusiastic) and 10 negative (e.g., upset, nervous) emotions in the past 30 days. Response options ranged from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely), resulting in a possible range of scores from 10 to 50 on each scale. The PANAS has strong psychometric properties, even when used for retrospective assessment of general mood over several weeks (Watson et al., 1988). Internal consistency in this sample was good across assessments (alphas ranged from .86 to .91 and .86 to .89 for the positive and negative affect scales, respectively). Mood was assessed at all 14 waves.

2.3.4. Alcohol Use

At each time point, participants responded to two items assessing past month alcohol use. The first item read, “In the past month, how often have you had some kind of beverage containing alcohol?” Participants chose among categorical response options, which were coded to represent average monthly frequency of drinking. Responses ranged from “never in the past month” (coded as 0) to “every day” (coded as 30). The second item asked, “In the past month, when drinking alcohol, how many drinks did you usually have on one occasion?” Response options ranged from “none” (coded as 0) to “nine or more total drinks” (coded as 9). Participants were provided with a definition of a standard drink before responding. The frequency and quantity variables were multiplied to provide an estimate of total past month alcohol quantity.

2.3.5 Alcohol Consequences

The 48-item Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006) assessed eight domains of negative alcohol-related consequences, which have been shown to load on a single, higher-order factor. Participants provided yes (coded 1) or no (coded 0) responses, indicating whether they had experienced that consequence in the past month. Research shows that the number of different types of alcohol consequences an individual endorses may be a better indicator of alcohol problem severity than the frequency of the consequences (Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005; Kahler, Strong, Read, Palfai, & Wood, 2004). So, a total score was created by summing responses to all items, with higher scores indicating greater severity of problematic drinking. Alcohol consequences were assessed at all 14 waves. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample ranged from .93 to .95 across the 14 assessments.

3. Data Analysis

To examine whether BIS and BAS moderated within-person associations between mood and alcohol consequences over time, we performed multilevel regression analyses using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.2. A multilevel modeling approach was chosen because it is well suited for analyzing within-person associations over time as well as between-person moderators of these associations.

Prior to conducting the analyses, descriptive statistics and distributional properties were examined for all variables. The alcohol consequences variable was log-transformed to help correct for non-normality. Each participant contributed up to 14 observations to each analysis. In both regression models, positive and negative mood were entered as predictors of alcohol consequences. To examine within-person associations, we created variables representing within-person mood changes. For within-person negative mood changes, we subtracted each person’s overall mean negative mood (averaged across the 14 assessments) from their negative mood scores at each time point. Thus, a positive score on this variable at a particular time point indicated a negative mood state that was higher than that person’s average negative mood. The same procedure was used to create a variable for within-person positive mood changes. To aid interpretation of the coefficients, these variables were standardized across all observations. Thus, values on the within-person negative mood variable represented within-person increases and decreases in negative mood in standard deviation units, relative to all negative mood changes across all time points and all participants. These variables were included as level 1 predictors in the models. Also, to control for between-person differences in average levels of mood, each person’s overall mean on positive and negative mood (grand mean centered and standardized) were included as level 2 covariates (Schwartz & Stone, 1998). In addition, to control for time-varying influences of alcohol use, the same procedure was used to derive variables representing within-person changes and between-person mean alcohol use, which also were included as covariates (Schwartz & Stone, 1998).

Further, we included a level 1 covariate representing a linear trend for year in college (year 1 = 0; year 2 = 1; year 3 = 2) to examine whether within-person associations between mood and problematic drinking differed over time. We coded our time effect at the level of year because assessments occurred within academic years at regular intervals with a larger interval over the summer months. This provided a natural breaking point for modeling the effects of time as year in college. Also, consistent with research showing that alcohol involvement is greater early in the first semester of college (Del Boca et al., 2004), we observed higher mean alcohol consequences during the early fall each year (see Table 1), followed by a decline and leveling off of consequences for the remainder of the academic year. Thus, we created a dummy-coded variable contrasting the early fall (September and October surveys coded as “1”) with the rest of the academic year (November, December, February, and April surveys coded as “0”), and included it as level 1 covariate to control for this seasonal variation. This variable was standardized across participants so that the intercept would reflect the yearly average. Because BIS and BAS are conceptualized as relatively stable individual difference traits, scores for these constructs at T1 were used as level 2 predictors to be examined as moderators of the within-person associations. Gender was entered as a level 2 covariate. Level 2 variables were standardized across participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Alcohol Consequences, Alcohol Use, and Positive and Negative Mood at Each Wave.

| Alcohol Consequences | Alcohol Use | Positive Mood | Negative Mood | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | ||

| Year 1 | September | 7.99 | 7.85 | 617 | 24.00 | 31.43 | 637 | 34.92 | 6.63 | 637 | 22.42 | 7.22 | 637 |

| October | 6.10 | 7.33 | 596 | 20.03 | 26.60 | 615 | 31.39 | 7.43 | 614 | 22.41 | 7.54 | 614 | |

| November | 5.49 | 7.53 | 583 | 19.01 | 28.33 | 597 | 30.33 | 8.00 | 596 | 22.18 | 7.92 | 596 | |

| December | 4.67 | 7.12 | 561 | 17.76 | 27.30 | 576 | 29.96 | 7.78 | 577 | 21.85 | 7.75 | 577 | |

| February | 5.92 | 8.32 | 544 | 23.57 | 33.20 | 551 | 29.76 | 7.70 | 555 | 21.64 | 7.84 | 555 | |

| April | 5.51 | 7.74 | 542 | 22.62 | 33.74 | 553 | 30.25 | 7.81 | 553 | 21.76 | 7.43 | 553 | |

| Mean | 5.99 | 6.56 | 637 | 21.23 | 25.21 | 637 | 31.13 | 6.11 | 637 | 22.18 | 6.21 | 637 | |

| Year 2 | September | 5.67 | 7.94 | 576 | 24.70 | 37.67 | 587 | 33.59 | 7.60 | 586 | 22.68 | 8.10 | 586 |

| December | 4.80 | 7.75 | 561 | 18.56 | 27.33 | 570 | 29.54 | 7.95 | 570 | 22.36 | 7.78 | 570 | |

| February | 4.85 | 7.65 | 548 | 19.65 | 28.49 | 555 | 30.61 | 7.45 | 555 | 21.77 | 7.92 | 555 | |

| April | 4.55 | 7.24 | 539 | 16.62 | 22.56 | 552 | 29.97 | 7.91 | 551 | 21.40 | 7.55 | 551 | |

| Mean | 5.03 | 6.84 | 603 | 19.90 | 25.62 | 605 | 30.92 | 6.42 | 605 | 22.29 | 6.74 | 605 | |

| Year 3 | September | 4.71 | 6.76 | 577 | 22.80 | 37.67 | 582 | 33.28 | 7.72 | 578 | 22.37 | 8.15 | 578 |

| December | 4.35 | 6.77 | 554 | 19.62 | 27.33 | 563 | 29.97 | 7.87 | 564 | 22.07 | 7.71 | 564 | |

| February | 4.33 | 6.72 | 551 | 20.80 | 28.49 | 554 | 30.22 | 7.83 | 551 | 21.09 | 7.75 | 551 | |

| April | 4.63 | 6.96 | 546 | 23.83 | 22.56 | 552 | 29.91 | 8.04 | 550 | 20.92 | 7.43 | 550 | |

| Mean | 4.53 | 5.93 | 595 | 21.72 | 28.94 | 595 | 30.83 | 6.63 | 594 | 21.71 | 6.61 | 594 | |

| Season | Early Fall | 6.17 | 6.13 | 637 | 22.91 | 26.27 | 637 | 33.18 | 5.93 | 637 | 22.59 | 6.30 | 637 |

| Late Fall | 4.94 | 6.05 | 624 | 18.72 | 23.05 | 625 | 29.91 | 6.47 | 623 | 22.23 | 6.44 | 623 | |

| Early Spring | 5.13 | 6.57 | 609 | 22.04 | 28.01 | 612 | 31.01 | 6.44 | 610 | 22.73 | 6.73 | 610 | |

| Late Spring | 4.96 | 6.25 | 599 | 21.18 | 26.53 | 599 | 29.99 | 6.52 | 599 | 21.48 | 6.23 | 599 | |

| Grand Mean | 5.37 | 5.71 | 637 | 21.04 | 23.07 | 637 | 30.89 | 5.72 | 637 | 22.17 | 5.90 | 637 | |

Note. Means for season are averages across the three years for that time of year. Alcohol use is estimate of total past-month quantity (i.e., quantity*frequency index). Early Fall = September and October assessments, Late Fall = November and December Assessments, Early Spring = February assessments, Late Spring = April assessments.

We hypothesized that the within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences would be moderated by the interaction between BIS and BAS, and that year in school would further moderate this association. To test this hypothesis, we entered the 4-way interaction between BIS, BAS, within-person negative mood, and year in college. We also entered all of the 2-and 3-way interactions among these 4 variables to obtain an appropriate estimate of the 4-way interaction (see Aiken & West, 1991). Further, we hypothesized that within-person associations between positive mood and alcohol consequences would be moderated by BAS and that this would depend on time. Although we did not have a priori hypotheses about the role of the BIS by BAS interaction in this association, we decided to explore these interactive effects given the importance of the Joint Subsystems Hypothesis to RST. Thus, consistent with the modeling of within-person negative mood, we included a 4-way interaction between BIS, BAS, within-person positive mood, and year in college, as well as the lower-order 2- and 3-way interactions among these variables.

Maximum likelihood estimation was used for the analyses. Random effects for the intercept and the slopes of all level 1 covariates (within-person positive and negative mood changes, within-person alcohol use changes, year in college, seasonal effects) were estimated sequentially and retained in the final model if they improved model fit. An unstructured covariance matrix was specified for the random effects (Littell, Miliken, Stroup, & Schabenberger, 2006). All fixed effects were added to the models simultaneously. The Kenward-Rogers correction was used to calculate degrees of freedom for fixed effects, helping to accommodate the unbalanced design resulting from missing data (see Littell et al., 2006). We first examined the highest-order interactions in the model (i.e., the 4-way interactions) because these provided tests of the main hypotheses.

To increase parsimony and simplify interpretation of lower-order coefficients, models were trimmed by removing all interactions that did not approach statistical significance (p > .10). Model trimming was conducted in a stepped fashion, by first removing nonsignificant 4-way interactions, followed by nonsignificant 3-way interactions, and finally by nonsignificant 2-way interactions. Two- and three-way interactions that were lower-order components of a significant higher-order interaction were retained regardless of their p-values because they are necessary for interpreting the higher-order interaction (Aiken & West, 1991). Significant interactions were probed by examining simple slopes for the associations between within-person mood changes and alcohol consequences (Aiken & West, 1991). We probed interactions involving BIS and BAS by examining lower-order effects conditioned on high (M+1SD) and low (M−1SD) levels of BIS and BAS. We probed interactions involving year in college by re-centering this variable on each of three years.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and number of participants for the mood variables and alcohol use and consequences at each wave. As shown in Table 1, mean alcohol consequences declined on average over the 3 years, while alcohol use remained more constant. Seasonal variation also was observed, with students reporting a greater number of alcohol consequences during the early fall assessments compared with the rest of the academic year. A similar, but less pronounced, seasonal pattern was observed for alcohol use. Between-person means (SD) for positive and negative mood (averaged across all waves) were 30.89 (5.72) and 22.17 (5.90), respectively. The standard deviations of the within-person mood changes (5.43 for positive and 5.06 for negative) suggested that average within-person variability in mood was comparable to between-person variability. Also, when looking across all participants and all waves, there was a considerable range between the overall lowest and overall highest observed scores on the within-person mood change variables (from −26.71 to 24.00 for positive and from −21.00 to 22.69 for negative.) The means (SD) for T1 BAS and BIS were 3.16 (0.38) and 3.08 (0.53), respectively.

4.2. Missing Data

Retention rates in this sample were high, with 83% of participants completing at least 12 of the 14 assessments. The mean number of complete assessments was 12.66 (SD = 2.74, range = 1–14). Because only participants with complete data at T1 were included in the study, no participants were missing data on level 2 variables (gender, BIS, BAS), allowing us to include all 637 participants in the analyses. Only 7% (n = 47) of the participants were missing data for an entire academic year or more and were considered study dropouts. Those who dropped out of the study did not differ significantly from participants who remained in the study on gender, ethnicity, family income, living arrangements, or T1 BIS, BAS, or alcohol consequences (all ps > .05). Those who dropped out of the study reported lower positive mood, higher negative mood, and lower high school GPA at T1 compared to those who remained in the study (ps < .05). BIS and BAS were assessed at T1 and all participants had complete data on these variables. Mood and alcohol consequences were assessed a total of 14 times, resulting in 8918 possible observations (14 assessments times 637 participants). A missing value on a mood or alcohol variable at a given time point resulted in exclusion of that participant’s data for that particular time point. The overall proportion of missing data was 12% (1047 missing observations out of 8918 possible observations).

4.3. Multilevel Model

A nested model test showed that including a random intercept significantly improved model fit relative to a model with no random effects, Δχ2(1)=2037.20, p <.001. Moreover, for most level 1 variables, the addition of the random slope and random covariance with the intercept further improved model fit (within-person negative mood, Δχ2(2)=34.80, p <.001; within-person positive mood, Δχ2(2)=7.00, p=030; within-person alcohol use, Δχ2(2)=692.5, p <.001; and year in college, Δχ2(2)=338.80, p <.001). Thus, all of these random effects were included in the model. However, the random seasonal effects for early fall did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(2)=2.70, p=259. Thus these random effects were removed from the model and within-person seasonal variation in alcohol consequences was modeled only as a fixed effect. Table 2 shows the random variance and covariance estimates for the final model.

Table 2.

Final Multilevel Regression Models Predicting Alcohol Consequences

| Fixed Effects | β | SE (β) | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | ||||||

| alcohol use changes (within-person) | .534** | .022 | 225 | <.001 | ||

| positive mood changes (within-person) | .017 | .011 | 1270 | .122 | ||

| negative mood changes (within-person) | .048** | .011 | 1365 | <.001 | ||

| year in college | −.102** | .012 | 576 | <.001 | ||

| seasonal effect for early fall | .073** | .007 | 6455 | <.001 | ||

| Level 2 | ||||||

| gender | −.114** | .022 | 626 | <.001 | ||

| mean alcohol use (between-person) | .467** | .021 | 630 | <.001 | ||

| mean positive mood (between-person) | −.053* | .022 | 629 | .014 | ||

| mean negative mood (between-person) | .124** | .023 | 638 | <.001 | ||

| Behavioral Approach System (BAS) | .085** | .024 | 656 | .001 | ||

| Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) | .053* | .026 | 685 | .041 | ||

| Interactions for Within-Person Negative Mood Changes negative mood changes * year in college * BAS*BIS |

.025** | .009 | 5537 | .006 | ||

| Lower-Order Interactions | ||||||

| negative mood changes * year in college * BAS | −.001 | .009 | 5320 | .914 | ||

| negative mood changes * year in college * BIS | −.009 | .009 | 5957 | .305 | ||

| negative mood changes * BAS* BIS | −.023* | .010 | 878 | .027 | ||

| negative mood changes * year in college | −.004 | .009 | 5863 | .636 | ||

| negative mood changes * BAS | .012 | .010 | 1008 | .232 | ||

| negative mood changes * BIS | .011 | .011 | 1330 | .310 | ||

| year in college * BAS*BIS | .007 | .012 | 574 | .567 | ||

| year in college * BAS | −.014 | .013 | 565 | .256 | ||

| year in college * BIS | −.021† | .013 | 591 | .095 | ||

| BIS*BAS | .014 | .022 | 644 | .523 | ||

| Interactions for Within-Person Positive Mood Changes positive mood changes * year in college |

−.018* | 0.009 | 5660 | 0.038 | ||

|

Random Effects Variance Covariance Matrix |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. intercept | .276** | |||||

| 2. alcohol use changes | −.006 | .155** | ||||

| 3. positive mood changes | −.004 | −.001 | .004* | |||

| 4. negative mood changes | .006 | .005 | .001 | .003* | ||

| 5. year in college | −.048** | −.008 | −.004† | .001 | .049** | |

Notes. Random effects variance-covariance matrix shows random variances on diagonal and random covariances off diagonal. Random effects included for level 1 variables based on nested model tests. Degrees of freedom for fixed effects based on Kenward-Rogers correction.

p≤.10

p≤.05

p≤.01.

Because we hypothesized that BIS and BAS would interact with one another to moderate the within-person associations between mood and alcohol consequences over time, we next examined the fixed effects estimates for the 4-way interactions between BIS, BAS, year in college, and within-person mood changes. The interaction between BIS, BAS, year in college, and within-person changes in negative mood was statistically significant (β=.026, SE=.009, p=.005). Thus, we retained this 4-way interaction and the lower-order 2- and 3-way interactions that comprised this interaction. However, the 4-way interaction between BIS, BAS, year in college, and within-person changes in positive mood was not statistically significant (β=.006, SE=.008, p=.445), so this interaction was trimmed from the model and the analysis was re-run. None of 3-way interactions involving within-person positive mood changes were significant (ps>.30) and were trimmed as well. Of the remaining 2-way interactions involving within-person positive mood changes, only the interaction between within-person positive mood and year in college was statistically significant (β=−.018, SE=.009, p=.034) and retained in the final model. Table 2 presents the final trimmed model. 2

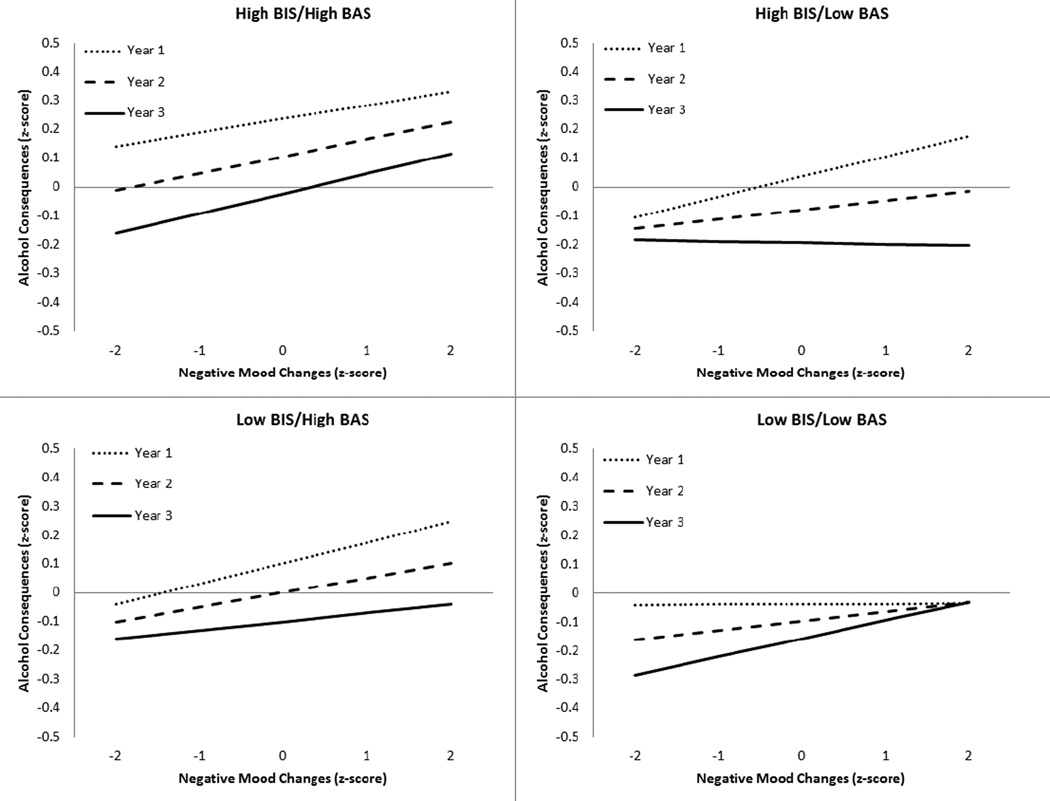

Next, we conducted simple slopes analyses to probe the significant 4-way interaction between BIS, BAS, year in college, and within-person negative mood. We examined lower-order associations conditioned on 4 combinations of BIS and BAS: high BIS/high BAS, high BIS/low BAS, low BIS/high BAS, and low BIS/low BAS (See Figure 1). Consistent with hypothesis 1, in the first year of college there was a significant within-person association between greater negative mood and greater alcohol consequences for students high on both BIS and BAS (β=.048, SE=.019, p=.010), for students high on BIS and low on BAS (β=.070, SE=.020, p<.001), and for students high on BAS and low on BIS (β=.072, SE=.023, p=.002); however, no within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences in the first year was observed for those low on both BIS and BAS (β=.001, SE=.023, p=.952). Consistent with hypothesis 2, the interaction between year in college and within-person negative mood was statistically significant only for individuals with a combination of high BIS and low on BAS (β=−.037, SE=.017, p=.027). For these individuals, the within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences diminished over time, with increases in negative mood predicting more alcohol consequences in the first (β=.070, SE=.020, p<.001) and second (β=.032, SE=.015, p=.033) years of college but not the third year (β=−.005, SE=.025, p=.836). However, consistent with hypothesis 2, the significant within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences did not diminish over time for individuals high on BAS, regardless of whether they were high on BIS (interaction β=.010, SE=.016, p=.507) or low on BIS (interaction β=−.021, SE=.019, p=.281). Also, the null relationship between within-person negative mood changes and alcohol consequences for students low on both BIS and BAS was not moderated by year in college (interaction β=.031, SE=.020, p=.114).

Figure 1.

Simple slopes for the within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences by year in school for students with a combination of high BIS and high BAS (top left), high BIS and low BAS (top right), low BIS and high BAS (bottom left), and low BIS and low BAS (bottom right).

We probed the significant interaction between within-person changes in positive mood and year in college (see Table 2), holding BIS and BAS constant. Results of simple slopes analyses showed that the within-person association between positive mood and alcohol consequences changed from slightly positive to slightly negative over time, although none of the simple slopes for this association were statistically significant (in year 1, β=.017, SE=.011, p=.122; in year 2, β=−.001, SE=.008, p=.859; in year 3, β=−.019, SE=.013, p=.129).

5. Discussion

This study helps to clarify within-person associations between mood and problematic alcohol use in college students, demonstrating that these associations depend on individual differences in BIS, BAS, and their interaction. This is the first study to examine the moderating role of BIS and BAS in the association between mood and alcohol consequences, thereby making an important contribution to the RST literature on alcohol use. Moreover, this study extends research on within-person mood-drinking associations that has tended to capture only relatively brief intervals of time, providing new insight into changes in these associations over several years of college. Thus, this study helps to improve our understanding of who is at risk for negative alcohol consequences in relation to global mood changes and when this risk is elevated in college.

We found that some students tended to have more negative alcohol consequences during months when they experienced greater levels of negative mood, after controlling for within-person changes in alcohol use. This finding is consistent with motivational models of drinking (Cooper et al., 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1988). Specifically, using alcohol when experiencing negative mood may increase the likelihood of drinking in risky situations and in ways that are maladaptive, leading to greater negative consequences that are not entirely accounted for by level of alcohol consumption (Cooper et al., 1995; Merrill & Read, 2010). Although we did not examine the mechanism linking negative mood to alcohol consequences in this study, our findings extend research on within-person associaitons between mood and drinking outcomes, providing evidence for these associations over longer time frames (i.e., within-person changes at the monthly level over several years).

The transition into college can be a stressful time for many students as they adjust to a new environment and new roles (Arnett, 2005). Our data suggest that elevations on BIS and/or BAS impact associations between global negative mood changes and negative alcohol consequences early in college. Consistent with our first hypothesis, findings revealed that students who were either high on BIS, high on BAS, or high on both BIS and BAS showed significant within-person associations between negative mood and alcohol consequences in the first year of college, whereas students low on both BIS and BAS did not. Although not directly assessed in this study, one reason that the association between negative mood and alcohol consequences may be stronger for individuals high on BAS is that they may be more sensitive the rewarding, tension reducing effects of alcohol. Thus, during periods of negative mood, these individuals may be more likely to use alcohol to obtain alcohol’s rewarding effects, resulting in more overall negative consequences. Also following from RST, the association between negative mood and alcohol consequences may be stronger for drinkers high on BIS because they may be more sensitive to the punishing consequences of alcohol and thus experience greater alcohol consequences during months when they are experiencing higher overall negative mood. Though speculative, our findings are consistent with these theoretical predictions of RST.

Our data show that for some students, the link between negative mood and alcohol consequences diminishes over time as students adjust to college life, but for others, this link persists over several years of college. Importantly, we found that BIS and BAS appear to moderate this process. Consistent with our second hypothesis, we found that individuals with a strong BAS (regardless of BIS strength) continued to show a within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences over the first three years of college. However, for students high on BIS, changes in the within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences depended on the strength of BAS. We observed decreases in the strength of the association between negative mood and alcohol consequences for students high on BIS and low on BAS. In contrast, this association remained strong for individuals high on both BIS and BAS.

These findings may be understood from the perspective of RST, which holds that BIS and BAS underlie sensitivity to reinforcement and punishment sensitivity (see Corr, 2008). We speculate that the within-person association between negative mood and alcohol consequences did not diminish over time for individuals high on BAS because of their heightened sensitivity to the reinforcing effects that alcohol has on mood. Conversely, high BIS may sensitize students to the punishing effects of mood-related drinking, and over time they may become less likely to drink during periods when they are experiencing elevations in negative mood. Yet this might be contingent upon levels of BAS. A strong BAS may shift the focus to the rewarding, tension reducing outcomes of using alcohol, and sustain the tendency to drink during periods of negative mood (see Wardell et al., 2011). Thus, the combination of a strong BIS and a strong BAS appears to maintain the association between negative mood and alcohol consequences over time, consistent with the Joint Subsystems Hypothesis (Corr, 2002). Yet, as we did not directly examine specific mechanisms of these associations, this interpretation is speculative.

For positive mood, within-person associations with alcohol consequences were slightly positive earlier in college and became slightly negative in later years. However, none of these simple slopes were statistically significant, suggesting that within-person changes in global positive mood had little association with alcohol consequences after controlling for alcohol use. Further, neither BIS nor BAS moderated within-person relations between positive mood and alcohol consequences. Our findings are consistent with at least some past studies that have found personality traits to moderate within-person associations between mood and drinking for negative mood but not for positive mood (e.g., Simons et al., 2010). However, more research is necessary to clarify whether BIS and BAS can have an influence on positive mood-drinking associations.

This study has some limitations. First, in broadening the scope of our within-person analysis to a three-year period, we relied on monthly timeframes for assessments and did not capture more fine-grained fluctuations in mood and alcohol use. Motivational models of drinking, and much of the research on the mood-drinking link, invoke primarily proximal mechanisms to describe mood influences on drinking outcomes (e.g., drinking immediately after having a bad day to cope with distress). These types of proximal mechanisms are best captured using fine-grained assessments (e.g., daily, or ecological momentary assessments). Yet, it is also important to go beyond examining the influences of mood on alcohol outcomes at a very proximal level and to examine patterns of mood-alcohol associations over the longer term. In doing so, we made the assumption that the same proximal processes described by motivational models of drinking might accumulate across many drinking episodes over time, and thus these same processes might help us understand the association between more long-term fluctuations in global mood and alcohol consequences at the monthly level. Though a reasonable assumption, it is important to note that in this study we do not provide an examination of the mechanisms that might link mood changes to alcohol consequences at this time scale. Similarly, the use of a quantity-frequency index of alcohol use ignores peak drinking, heavy episodic drinking episodes, and other patterns of alcohol use that are not reflected in “typical” quantity and frequency aggregated over a one month period.

In addition, although our analysis allowed us to examine whether within-person changes in mood were associated with corresponding changes in alcohol consequences, the results are nonetheless correlational and do not permit causal inferences. We interpreted the results in terms of mood changes influencing alcohol consequences, consistent with motivational theory. Yet, because mood and alcohol consequences were measured concurrently at each time point, we cannot rule out the possibility that the influence between mood and alcohol consequences also could be in the opposite direction, such that experiencing more negative consequences increased negative mood. More research is needed to elucidate the directionality of within-person associations between mood and alcohol consequences and the role of BIS and BAS in these processes.

It also is possible that elevations on negative mood or BIS could have increased the perceived severity of negative alcohol consequences, making it more likely that these consequences were reported during the assessment. However, it should be noted that the perception of alcohol consequences is an important process in itself (Mallett, Bachrach, & Turrisi, 2008; Merrill, Read, & Barnett, in press). Individuals who perceive their negative alcohol consequences as more severe may be more distressed by their drinking, which in itself contributes to the problematic nature of their drinking behavior. Thus, the associations between negative mood, BIS, and alcohol consequences may still be clinically relevant even if they are driven more by subjective, rather than objective, experience of consequences. This will be an important avenue for future research. Similarly, future research in this area should include measures of positive alcohol-related outcomes to examine whether BIS and BAS might influence the links between mood and positive consequences (both objective and subjective).

Our sample was drawn from a larger study investigating trauma and substance use, and was selected to over-represent PTSD symptoms at T1. However, we do not believe that our recruitment approach greatly influenced the generalizability of our findings, as mean BIS and BAS scores and rates of alcohol use and consequences were comparable to general college samples (Carver & White, 1994; O'Connor, Stewart, & Watt, 2009; Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007), and we did not find evidence that selection status based on PTSD criteria moderated any of the associations we observed. Still, future research should replicate our findings with an unselected sample of drinkers. Similarly, the response rate to the initial screening survey may limit the generalizability of the findings, as a sizable proportion of eligible participants were not part of our initial subject pool.

Also, the effects we observed were relatively small. However, interaction effect sizes in the social sciences tend to be small (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003), and even small interactions provide meaningful insights into the nature of the associations among variables. Still, the practical significance of the findings must be interpreted in the context of their small effect sizes.

In summary, this study extends research on the associations between mood and negative alcohol consequences in college students by showing that these associations change over time as a function of BIS, BAS, and their interaction. The findings suggest that BIS and BAS are useful traits for identifying which student may be at greater risk for alcohol-related consequences during periods of negative mood and when this risk is elevated in college.

Highlights.

We examine within-person associations among mood and alcohol consequences.

We model behavioral approach (BAS) and inhibition systems (BIS) as moderators.

We examine these processes over three years of college.

Negative mood predicts more alcohol consequences for those high on BAS and/or BIS.

BAS and BIS interact to influence mood-alcohol consequence relations over time.

Acknowledgements

Role of Funding Sources

The National Institute on Drug Abuse did not have a role in the design of the study, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA018993) to Dr. Jennifer P. Read. We would like to thank Drs. Paige Ouimette, Craig Colder, and Jackie White for their contributions to this project’s conceptualization and implementation. We also thank Sherry Farrow, Jennifer Merrill, Ashlyn Swartout, Leah Vermont, and all of the other members of the Alcohol Research Lab at the University at Buffalo whose efforts made this research possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Research suggests that drinking to regulate negative mood may be less common among college students than social or celebratory drinking (see Kuntsche et al., 2005) and may increase as students transition into adult roles. However, there is evidence that drinking to cope with negative emotions still does occur for a subsample of students (Hussong et al., 2001; Mohr et al., 2005; Park & Levenson, 2002). For these students, the association between negative mood and alcohol consequences may be stronger early in college due to the stress of this transition period.

Because our sample was selected to overrepresent participants with PTSD symptomatology, and PTSD is known to be related to mood and alcohol outcomes, we performed secondary analyses to explore the role of PTSD group selection status. To do so, we created a dummy coded variable to indicate which participants were selected to represent the PTSD group (i.e., those above threshold on PTSD symptom cut-off; see method) and which participants were randomly selected as controls (i.e., those below these symptom cut-offs). We then entered this variable into our multilevel model as level 2 covariate. First, we examined the main effect of PTSD selection status, and found that it did not predict unique variance in alcohol consequences (p = .455). Next, we examined whether the associations we observed between mood and alcohol consequences, as well as the impact of BIS and BAS on these associations, were moderated by PTSD selection status. To do so, we entered interactions between the PTSD selection status and within-person mood, BIS, BAS, year in school, and all interactions among these variables that were part of the final trimmed model. We first examined the highest-order interaction with PTSD status, and then trimmed nonsignificant interactions to evaluate the significance of the lower order interactions. The results showed that none of the relevant interactions involving PTSD selection status and mood were statistically significant (ps > .10), suggesting that trauma selection status did not further moderate the mood-alcohol consequence associations in this study.

Author Disclosures

Contributors

All authors contributed substantively to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the conceptualization of the study. Jennifer P. Read designed the study protocol and secured funding to collect the data. Jeffrey D. Wardell conducted the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Craig R. Colder contributed to the study conceptualization and provided guidance with the data analysis. All authors provided conceptual input at various stages of the manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors ensure that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Tennen H, Affleck G, Kranzler HR. Does affect mediate the association between daily events and alcohol use? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:862–871. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Todd M, Mohr C. A daily process approach to individual differences in stress-related alcohol use. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1657–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Blume AW, McKnight P, Marlatt GA. Brief intervention for heavy-drinking college students: 4-year follow-up and natural history. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr PJ. J. A. Gray's reinforcement sensitivity theory: Tests of the joint subsystems hypothesis of anxiety and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;33:511–532. [Google Scholar]

- Corr PJ. Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST): Introduction. In: Corr PJ, editor. The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles DM, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and self-efficacy as predictors of heavy drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The neuropsychology of emotion and personality. In: Stahl SM, Iversen SD, Goodman EC, editors. Cognitive neurochemistry. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 1987. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. Incorporating social anxiety into a model of college student problematic drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:127–150. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, Seibring M. Attendance and alcohol use at parties and bars in college: A national survey of current drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Drugs. 2002;63:726–733. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt NE, Kimbrel NA, Mitchell JT, Nelson-Gray RO. High BAS, but not low BIS, predicts externalizing symptoms in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:565–575. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Hicks RE, Levy SA, Curran PJ. Specifying the relations between affect and heavy alcohol use among young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:449–461. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Alcohol use disorders and psychological distress: A prospective state-trait analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:599–613. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP, Palfai TP, Wood MD. Mapping the continuum of alcohol problems in college students: A Rasch model analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:322. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Miliken WW, Stroup RDW, Schabenberger O. SAS for mixed models. 2nd ed. Cary, N. C: SAS Institute Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Vergara HI, Colder CR, Hawk LW, Jr., Wieczorek WF, Eiden RD, Lengua LJ, Read JP. Reinforcement sensitivity theory and alcohol outcome expectancies in early adolescence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:130–134. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students' perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Barnett NP. The way one thinks affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, Carney MA. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G, Allen NB, Trinder J. A longitudinal investigation of seasonal variation in mood. Chronobiology International. 2001;18:875–891. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100107522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Geisner IM, Lee CM. Perceived marijuana norms and social expectancies among entering college student marijuana users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:433. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RM, Colder CR. Predicting alcohol patterns in first-year college students through motivational systems and reasons for drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:10–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RM, Stewart SH, Watt MC. Distinguishing BAS risk for university students’ drinking, smoking, and gambling behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:514–519. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare T. Measuring excessive alcohol use in college drinking contexts: the Drinking Context Scale. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Y, Aguilar R, Molinuevo B, Torrubia R. Alcohol use as a behavioural sign of disinhibition: Evidence from JA Gray's model of personality. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32:2398–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins H. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol S14. 2002:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin LA, Maggs JL. First-year college student affect and alcohol use: Paradoxical within- and between-person associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:925–937. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Ouimette P, White J, Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychology. 1998;17:6–16. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: Effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MN, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:459–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zeitlin SB, Samoluk SB. Examination of a three-dimensional drinking motives questionnaire in a young adult university student sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00036-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt DC, Dillard JP, Braddock KH, Anderson JW, Sopory P, Stephenson MT. BIS/BAS scales and their relationship to risky health behaviours. Personality and individual differences. 2009;47:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, O’Connor RM, Read JP, Colder CR. Behavioral approach system moderates the prospective association between the behavioral inhibition system and alcohol outcomes in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:1028–1036. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE. Positive alcohol expectancies mediate the influence of the behavioral activation system on alcohol use: A prospective path analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School Of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O, Yaeger A. Contributions of positive and negative affect to adolescent substance use: Test of a bidimensional model in a longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:327–338. [Google Scholar]