Abstract

We identified 75 dehydration-responsive element-binding (DREB) protein genes in Populus trichocarpa. We analyzed gene structures, phylogenies, domain duplications, genome localizations, and expression profiles. The phylogenic construction suggests that the PtrDREB gene subfamily can be classified broadly into six subtypes (DREB A-1 to A-6) in Populus. The chromosomal localizations of the PtrDREB genes indicated 18 segmental duplication events involving 36 genes and six redundant PtrDREB genes were involved in tandem duplication events. There were fewer introns in the PtrDREB subfamily. The motif composition of PtrDREB was highly conserved in the same subtype. We investigated expression profiles of this gene subfamily from different tissues and/or developmental stages. Sixteen genes present in the digital expression analysis had high levels of transcript accumulation. The microarray results suggest that 18 genes were upregulated. We further examined the stress responsiveness of 15 genes by qRT-PCR. A digital northern analysis showed that the PtrDREB17, 18, and 32 genes were highly induced in leaves under cold stress, and the same expression trends were shown by qRT-PCR. Taken together, these observations may lay the foundation for future functional analyses to unravel the biological roles of Populus' DREB genes.

1. Introduction

Environmental stresses, such as drought, high salt, and low temperature, have adverse effects on plant growth and development. During evolution, plants established physiological and metabolic defense system responses to adverse conditions. In essence, stress induced the expression of specific genes and their products play a role in the plant's stress defense mechanism. Transcription factors (TFs) can upregulate a set of genes under their control by interacting with cis-elements present in the promoter region of targeted genes. The products act as regulatory proteins, consequently enhancing the stress tolerance of the plant. The dehydration-responsive element-binding (DREBs) protein TFs play an important role in regulating plant growth and the response to external environmental stresses.

In the plant kingdom, DREB is a large subfamily belonging to the APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element-binding protein (AP2/EREBP) family. DREB genes contain the highly conserved AP2/ERF DNA-binding domain [1]. The AP2/ERF domains, which consist of 50 to 60 amino acids, are found in proteins involved in a variety of regulatory mechanisms throughout the plant life cycle. The DREB subfamily play an important role in the resistance of plants to abiotic stresses by recognizing the dehydration-responsive element (DRE), which has a core motif of A/GCCGAC [2], and some members of this gene subfamily recognize the cis-acting element AGCCGCC, known as the GCC box [3]. The DREB subfamily TFs have been identified in various plant species, including mangrove [4], soybean [5], and potato [6]. The roles of DREB proteins in the plant's response to abiotic stress have also been extensively documented [7]. In the genomes of Arabidopsis [3], Vitis vinifera [8], and rice [9], 56, 36, and 57 AP2/ERF-related proteins, respectively, are encoded. Genetic and molecular approaches have been used in combination to characterize a series of DREB family regulatory genes involved in many different pathways, including genes related to cold, drought, high salinity, heavy metals, and abscisic acid (ABA) [4].

The characterization of the DREB subfamily of genes in Populus can aid the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of stress resistance and thus aid in the development of Populus varieties, using transgenic technology, with a greater tolerance to many adverse environments. Some DREB subfamily genes have been isolated from rice, Arabidopsis, and other plants [10], but they have not been isolated from Populus. Thus, their functions remain to be determined in Populus. The completion of the high-quality sequencing of the Populus genome [11] has provided an excellent opportunity for genome-wide analysis of genes belonging to specific gene families. Therefore, we present a comprehensive and specific analysis of gene structure, chromosome localization, and expression of the Populus' DREB subfamily for the first time. Here, we identified 75 PtrDREB genes in Populus using database searches and classified these genes according to their homology with known genes. We describe DREB subtypes more specifically and present novel information from different tissues and/or developmental stages. Some subtypes of this gene subfamily were differentially expressed under abiotic stress conditions. PtrDREB genes play an important role in the cross-talk of signaling pathways responding to different kinds of stress. We analyzed the phylogenetic relationships of the DREB genes in Populus and attempted the complete alignment of the subtypes. We examined gene structure and conserved motifs of DREB genes. Taken together, our results will be helpful in determining the functions of each DREB gene.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Search and Sequence Retrieval

The P. trichocarpa genome DNA database was downloaded from Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/). The database of the A. thaliana DREB subfamily was downloaded from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR, http://www.arabidopsis.org/, release 10.0). A local BLAST search was performed using the amino acid sequences of the AP2/ERF domains from Arabidopsis as the queries for the identification of the DREB genes from Populus. All of the located sequences were further manually analyzed to confirm the presence of an AP2 domain using the InterProScan program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/InterProScan/). The Arabidopsis At4g13040 was used as an outlier.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

A phylogenetic analysis was initially performed using all the DREB genes from Arabidopsis and Populus. To construct the phylogenetic trees, full-length Arabidopsis and Populus amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalX 1.83 software [12] and manually edited using Jalview to reduce gaps [13]. The phylogenetic analysis was performed by the maximum parsimony method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA 4 software [14].

2.3. Chromosome Localization

Each of the DREB genes' chromosomal position in Populus was identified and plotted using the Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/) and Joint Genome Institute (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/pages/blast.jsf?db=Poptr1_1) websites. This information is provided in Table 2. A schematic view of the chromosomes was reorganized by the most recent whole-genome duplication in Populus.

Table 2.

The DREB genes identified from the P. trichocarpa genome.

| Gene symbol | Gene Locus | PF00847 AP2 domain | Arabidopsis ortholog locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| PtrDREB1 | POPTR_0008s07120 | 102–151 | AT1G12610.1 |

| PtrDREB2 | POPTR_0010s19370 | 147–196 | AT1G63030.1 |

| PtrDREB3 | POPTR_0006s10510 | 67–125 | AT4G25470.1 |

| PtrDREB4 | POPTR_0016s13380 | 74–132 | AT4G25480.1 |

| PtrDREB5 | POPTR_0006s05320 | 28–78 | AT4G25490.1 |

| PtrDREB6 | POPTR_0016s05360 | 29–78 | AT5G51990.1 |

| PtrDREB7 | POPTR_0010s19100 | 78–128 | AT1G75490.1 |

| PtrDREB8 | POPTR_0008s07360 | 78–128 | AT2G38340.1 |

| PtrDREB9 | POPTR_0005s25470 | 43–92 | AT2G40340.1 |

| PtrDREB10 | POPTR_0002s03090 | 40–89 | AT2G40350.1 |

| PtrDREB11 | POPTR_0001s32250 | 285–333 | AT3G11020.1 |

| PtrDREB12 | POPTR_0017s08250 | 276–324 | AT3G57600.1 |

| PtrDREB13 | POPTR_0003s13910 | 107–155 | AT5G05410.1 |

| PtrDREB14 | POPTR_0019s13330 | 232–281 | AT5G18450.1 |

| PtrDREB15 | POPTR_0013s13920 | 232–281 | AT2G40220.1 |

| PtrDREB16 | POPTR_0005s07900 | 173–222 | AT1G01250.1 |

| PtrDREB17 | POPTR_0002s09480 | 163–211 | AT1G12630.1 |

| PtrDREB18 | POPTR_0007s05690 | 173–222 | AT1G33760.1 |

| PtrDREB19 | POPTR_0005s16690 | 120–168 | AT1G63040.1 |

| PtrDREB20 | POPTR_0003s17830 | 7–56 | AT1G71450.1 |

| PtrDREB21 | POPTR_0001s14720 | 46–95 | AT1G77200.1 |

| PtrDREB22 | POPTR_0018s02280 | 7–56 | AT2G25820.1 |

| PtrDREB23 | POPTR_0006s27710 | 7–56 | AT2G35700.1 |

| PtrDREB24 | POPTR_0018s01680 | 5–55 | AT2G36450.1 |

| PtrDREB25 | POPTR_0006s26990 | 21–71 | AT2G44940.1 |

| PtrDREB26 | POPTR_0003s02750 | 5–55 | AT3G16280.1 |

| PtrDREB27 | POPTR_0006s06870 | 5–55 | AT3G60490.1 |

| PtrDREB28 | POPTR_0018s13130 | 5–55 | AT4G16750.1 |

| PtrDREB29 | POPTR_0006s08000 | 22–71 | AT4G32800.1 |

| PtrDREB30 | POPTR_0007s10750 | 22–71 | AT5G11590.1 |

| PtrDREB31 | POPTR_0005s18430 | 22–71 | AT5G25810.1 |

| PtrDREB32 | POPTR_0002s12550 | 35–84 | AT5G52020.1 |

| PtrDREB33 | POPTR_0014s02530 | 35–84 | AT1G19210.1 |

| PtrDREB34 | POPTR_0018s00700 | 14–63 | AT1G21910.1 |

| PtrDREB35 | POPTR_0006s14110 | 14–63 | AT1G22810.1 |

| PtrDREB36 | POPTR_0005s15830 | 31–80 | AT1G44830.1 |

| PtrDREB37 | POPTR_0002s08610 | 26–76 | AT1G46768.1 |

| PtrDREB38 | POPTR_0019s10220 | 29–78 | AT1G71520.1 |

| PtrDREB39 | POPTR_0013s10420 | 20–70 | AT1G74930.1 |

| PtrDREB40 | POPTR_0018s08320 | 18–68 | AT1G77640.1 |

| PtrDREB41 | POPTR_0006s23480 | 23–73 | AT2G23340.1 |

| PtrDREB42 | POPTR_0006s14090 | 16–66 | AT3G50260.1 |

| PtrDREB43 | POPTR_0006s14100 | 16–66 | AT4G06746.1 |

| PtrDREB44 | POPTR_0001s18180 | 15–65 | AT4G31060.1 |

| PtrDREB45 | POPTR_0013s10340 | 14–64 | AT4G36900.1 |

| PtrDREB46 | POPTR_0019s10420 | 11–62 | AT5G21960.1 |

| PtrDREB47 | POPTR_0003S05300 | 16–66 | AT5G67190.1 |

| PtrDREB48 | POPTR_0013s10330 | 49–99 | AT1G36060.1 |

| PtrDREB49 | POPTR_0019s10430 | 15–65 | AT1G64380.1 |

| PtrDREB50 | POPTR_0019s09530 | 36–84 | AT1G78080.1 |

| PtrDREB51 | POPTR_0014s09540 | 38–88 | AT2G22200.1 |

| PtrDREB52 | POPTR_0855s00200 | 20–68 | AT4G13620.1 |

| PtrDREB53 | POPTR_0002s17330 | 20–68 | AT4G28140.1 |

| PtrDREB54 | POPTR_0006s02180 | 44–93 | AT4G39780.1 |

| PtrDREB55 | POPTR_0016s02010 | 50–98 | AT5G65130.1 |

| PtrDREB56 | POPTR_0015s13840 | 84–132 | AT1G22190.1 |

| PtrDREB57 | POPTR_0012s13880 | 115–163 | AT4G13040.1 |

| PtrDREB58 | POPTR_0003s12120 | 14–61 | |

| PtrDREB59 | POPTR_0001s08740 | 14–61 | |

| PtrDREB60 | POPTR_0009s14990 | 57–108 | |

| PtrDREB61 | POPTR_0004s19820 | 59–110 | |

| PtrDREB62 | POPTR_0001s08710 | 66–116 | |

| PtrDREB63 | POPTR_0001s08720 | 62–111 | |

| PtrDREB64 | POPTR_0012s13870 | 85–135 | |

| PtrDREB65 | POPTR_0015s13830 | 79–129 | |

| PtrDREB66 | POPTR_0002s14210 | 94–143 | |

| PtrDREB67 | POPTR_0003s07700 | 96–146 | |

| PtrDREB68 | POPTR_0001s15550 | 71–122 | |

| PtrDREB69 | POPTR_0003s04920 | 87–137 | |

| PtrDREB70 | POPTR_0001s18800 | 54–103 | |

| PtrDREB71 | POPTR_0018s09270 | 69–119 | |

| PtrDREB72 | POPTR_0006s17670 | 67–117 | |

| PtrDREB73 | POPTR_0006s25500 | 59–109 | |

| PtrDREB74 | POPTR_0018s00270 | 59–109 | |

| PtrDREB75 | POPTR_0014s05500 | 90–139 |

2.4. Exon/Intron Structure and Motif Analysis

The exon/intron organization for individual DREB genes was illustrated using the Gene structure display server (GSDS) program (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). The CDS and genome sequences of the P. trichocarpa genes were obtained from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The program MEME (v4.3.0) (http://meme.sdsc.edu/) was used to deduce 75 Populus DREB protein sequences.

2.5. EST Profiling and Microarray Analysis

The expression profile for each gene was obtained by a Digital Northern tool at PopGenIE (http://www.popgenie.org/) that generated a digital northern expression profile heat map based on the EST representations of 19 cDNA libraries derived from different tissues and/or developmental stages [15]. The heat map was visualized using the Heatmapper Plus tool at the Bio-Array Resource for Plant Functional Genomics (http://bar.utoronto.ca/ntools/cgi-bin/ntools_heatmapper_plus.cgi/) [16]. The microarray data for various tissues/organs available at NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the series accession number GSE6422 were used for the tissue-specific expression analysis.

2.6. Plant Treatment and qRT-PCR Analysis

For expression pattern analysis of the Populus DREB gene subfamily under abiotic stresses, plants were exposed to 42°C for 0, 0.5, and 1 h; 4°C for 0, 12, and 24 h; 200 mM NaCl for 0, 4, and 8 h; 100 μM ABA for 0, 2, 4, and 6 h; and 4% PEG6000 for 0, 4, and 8 h. Young leaves were harvested at various time points. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation.

Total RNA from leaf was extracted using the CTAB method. Synthesized cDNAs were used for qRT-PCR, which was performed using the TaKaRa ExTaq RT PCR Kit and SYBR green dye (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) in 96-well optical reaction plates (Applied Biosystems, USA). The results obtained for the different stages were standardized to the levels of the actin gene using the 2−ΔΔCT method. We selected 15 DREB genes to observe tolerance under stress conditions in Populus via EST profiling and microarray analysis. We designed the primers for gene expression analysis using Primer Premier 5 to produce amplified lengths of 180 to 200 bp (Table 1).

Table 1.

The primers of DREB genes were generated in Primer 5 for qRT-PCR.

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| PtrDREB4F | GTATTGAGGGGAGAAATGGATGG |

| PtrDREB4R | CATATCATGGTCGGAAGACAAGC |

| PtrDREB16F | AATCTTGCTACCACCACATCACAGT |

| PtrDREB16R | ATGCCTCCGCCTGACTCCTCTAT |

| PtrDREB17F | ACTCTGGCTTGGCACATTTGAC |

| PtrDREB17R | GGCTTGTATTCGCCGATGTAGGA |

| PtrDREB18F | GGCTCCAAAACCTGTCCCTATGA |

| PtrDREB18R | CCCAATGTCTCTGCCTCACTCCT |

| PtrDREB19F | GAGGAGGCGGCTTTGGCTTAT |

| PtrDREB19R | AACCGAGGAATGGAGAGGCTTG |

| PtrDREB28F | CAGTCAAAAAAGTTCAGAGGGGT |

| PtrDREB28R | CTCTTCTGCTGTTTCAAATGTGC |

| PtrDREB30F | GCATGTAACGGTAGAAAGGAGGGGG |

| PtrDREB30R | AGATTGGCGGTAGATCAAGAGTG |

| PtrDREB32F | AGAAGGAAGTCATCAACAAGGGG |

| PtrDREB32R | ATTTGGTGCAGGCTGAGGCAA |

| PtrDREB38F | GTGAGAGGCAATACAAGGGGA |

| PtrDREB38R | CGCTACTGGTGTTGAGTAGGAA |

| PtrDREB51F | TGACCCGACCTCAAACTCTCCAG |

| PtrDREB51R | TCAGACACCCATTTCCCCCACCT |

| PtrDREB55F | GATTCTCAACCAACCAAAACCTC |

| PtrDREB55R | GGCTCTCTAATTTCAGACACCCA |

| PtrDREB60F | GAAGAAGAACAAAGCGGGAAGGA |

| PtrDREB60R | CATTTCTGGGCTCTTGAAGGTCC |

| PtrDREB61F | GCAGGAAGGAAGAAGTTCAAGGA |

| PtrDREB61R | GGCTAGTGAAGGTCCCTAACCAAAT |

| PtrDREB62F | TCTTCTTTCTCCGATAGCAGCAC |

| PtrDREB62R | CACCCTATTGTTACCATTCCTCT |

| PtrDREB68F | TCTAAGCGAAACCAAGACCCGAA |

| PtrDREB68R | TTTGCCCCATTGACGCATTCT |

| ActinF | CATCAAAGCATCGGTGAGGTC |

| ActinR | GTTGCCATCCAGGCTGTCC |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of DREB Subfamily TFs in Populus

To identify putative DREB genes in Populus, we performed a BLASTP search against Populus genome release v2.1 using DREB protein sequences from Arabidopsis. By removing the redundant sequences, 75 DREB genes were identified in the Populus genome. All DREB candidates were analyzed using the smart database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/set_mode.cgi?NORMAL=1) to verify the presence of AP2/ERF domains. Seventy-five DREB genes were used for the analysis of bioinformatics and gene expression profiling. The overall strategy used in this study was depicted in Figure 1 and presented in detail below. We designated Populus DREB genes as PtrDREB following the nomenclature proposed in a previous study [17]. A. thaliana At4g13040 was used as a query sequence and it includes an AP2/ERF-like domain sequence; however, its homology appears quite low in comparison with the other AP2/ERF genes. Therefore, this gene was also designated as an outlier. Detailed information on the DREB subfamily of genes in Populus and Arabidopsis are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Integrated systems analysis workflow for elucidation of the role of DREB subfamily in the bioinformatics and data analysis in Populus. A: A phylogenetic analysis was performed using all the DREB subfamily amino acid sequences from Arabidopsis and Populus by MEGA 4 software. B: Each of the DREB genes' chromosomal position in Populus was using the Phytozome and Joint Genome Institute websites. C: The exon/intron organization for individual DREB genes was using the gene structure display server (GSDS) program and motif analysis was performed using the program MEME (v4.3.0). D: Gene expression profiling of Populus DREB subfamily was used to characterize differentially expressed genes.

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationships and Alignments of the DREB Subfamily in Populus

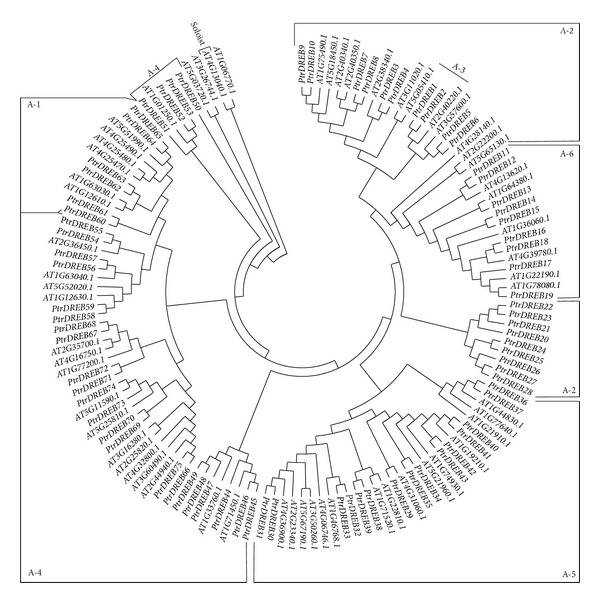

Based on the alignment of the AP2/ERF coding region protein sequences of all Populus and Arabidopsis DREB subfamily genes, 75 DREB subfamily genes of Populus were classified into six groups, A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6, containing six, 17, two, 26, 15, and nine members, respectively. The phylogenetic trees of the DREB subfamilies of Populus and Arabidopsis are shown in Figure 2. The alignment analysis indicates that DREBs share high homology in the AP2/ERF domain (see Supplementary Figure 1; available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/954640) and contain a conserved WLG motif in the AP2/ERF domain of Populus. In the proteins encoded by DREBs, position 14 is normally valine and position 19 is glutamic acid. This region may play an important role in the recognition of different DNA-binding sites by the DRE and GCC box cis-elements of the DREB subfamily [3]. Also, the DREBs contain alanine at position 319 in the β-sheet. Group A-1 possesses a conserved C/SEV/LR amino acid sequence between V319 and E324, and this region is converted into an AEIR amino acid sequence in groups A-2, A-3, and A-6. In Group A-4, Ser-324 is crucial for the specific binding of the ERE element, and Ser-324/Ala-324 is crucial in Group A-5.

Figure 2.

Relationships among Populus DREBs proteins after alignment with ClustalW. Proteins were allocated to six distinct subgroups of DREB, A-1 to A-6.

3.3. Chromosomal Locations of DREB Subgroups

To examine the genomic distribution of DREB genes on Populus chromosomes, we identified their positions by a Phytozome database search. In silico mapping of the gene loci showed that 75 Populus DREB genes were mapped to linkage groups (LG) (Figure 3). Previous studies revealed that the Populus genome has undergone genome-wide duplications followed by multiple segmental duplications, tandem duplications, and transposition events [18]. It was very clear that three pairs of genes were arranged in tandem repeats, LG I (PtrDREB63 and 64), LG II (PtrDREB52 and 53), and LG VI (PtrDREB43 and 42), and 18 pairs of genes were duplicated. The dN/dS ratios from the 18 segmental duplication pairs were less than 0.5. About 56% (42 of 75) of Populus DREBs were preferentially retained tandem duplications and multiple segmental duplication events. Tandem duplications and segmental duplications were relatively underrepresented in groups A-1 to A-6 with rates of 67% (4 of 6), 47% (8 of 17), 100% (2 of 2), 53% (14 of 26), 40% (5 of 15), and 89% (8 of 9), respectively. This finding corroborates previous findings that genes involved in transcriptional regulation and signal transduction are preferentially retained following duplications [19].

Figure 3.

Locations of P. trichocarpa DREB genes on the chromosomes LGI-XIX. A schematic view of chromosome reorganization by recent whole-genome duplication in Populus is shown (adapted from [21]). Regions that are assumed to correspond to homologous genome blocks are shaded in the same color and connected with lines.

3.4. Gene Structure and Conserved Motifs of Populus DREB Genes

To gain further insights into the structural diversity of Populus DREB genes, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using the full-length DREB protein sequences of Populus (Figure 4(a)). We compared the exon/intron organization in the coding sequences of each Populus DREB gene (Figure 4(b)). All but nine Populus DREB members had no introns in their coding regions and the nine Populus DREB genes had one intron (PtrDREB60, 61, 62, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, and 3). We predicted conserved motifs using MEME motif detection software that revealed the diversification of the P. trichocarpa DREB genes (Figure 4(c)), and 15 distinct motifs were identified (Table 3). The AP2/ERF domain consists of three β-sheet and one α-helix at the N termini [20, 21]. In this study, motif 3, specifying β-sheet strand 1; motif 1, specifying β-sheet strand 2 and 3; and motif 2, corresponding to the α-helix, were present in all of the Populus' DREB subfamily members. The CBF signature sequences (motif 14) were found in DREB Group A-1 [20, 21]. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis DREB Group A-1 TFs demonstrated significant similarity in the AP2/ERF binding domain and the CBF signature sequences [22]. These results suggest that the P. trichocarpa DREB Group A-1 share remarkable similarities at the amino acid sequence level with known CBF/DREB proteins of Arabidopsis and carry critical amino acids that are needed for binding to the CRT elements in the target genes. The CMIV domain (motif 7) was found in the DREB Group A-2. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis DREB Group A-2 TFs in the N-terminal region included the conserved motif CMIV-1 and the DNA-binding domain [23]. These results suggest that most of the closely related members in the phylogenetic tree shared a common motif composition with each other, suggesting functional similarities among the DREB proteins within the same subfamily.

Figure 4.

Phylogenomic analysis of 75 DREB genes in P. trichocarpa (a) with the integration of exon/intron structures (b) and MEME motifs (c). Exon/intron structure was obtained from the Gene Structure Display Server. Motifs were identified with the MEME software using the complete amino acid sequences of the DREB genes.

Table 3.

Motif sequences of DREB genes identified in P. trichocarpa by MEME tools.

| Motif | Width | Best possible match |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | WGKWVCEIREPRKKSRIWLGT |

| 2 | 24 | FPTPEMAARAHDVAALCIKGDSAI |

| 3 | 11 | KHPVYRGVRMR |

| 4 | 21 | LPVPASTSPRDIQAAAASAAA |

| 5 | 8 | LNFPDLVH |

| 6 | 25 | EEALFDMPNLLVDMAGGMLLSPPRI |

| 7 | 29 | GDGGNKPVRKVPAKGSKKGCMKGKGGPEN |

| 8 | 15 | EDHHIEQMIEELLDR |

| 9 | 18 | YKPLHSSVDAKLQAICQS |

| 10 | 25 | HIGVWQKKAGSRSSSNWVMKVELGN |

| 11 | 15 | GPITVRLSPSQIQAI |

| 12 | 30 | DMSAASIRKRATEVGAHVDAIETALNHHHH |

| 13 | 29 | STSSLTSLVSLMDLSSQEEELCEIVELPS |

| 14 | 21 | EVMLASRNPKKRAGRKKFRET |

| 15 | 21 | FESGNFMLQKYPSYEIDWASI |

3.5. EST Profiling and Microarray Analysis

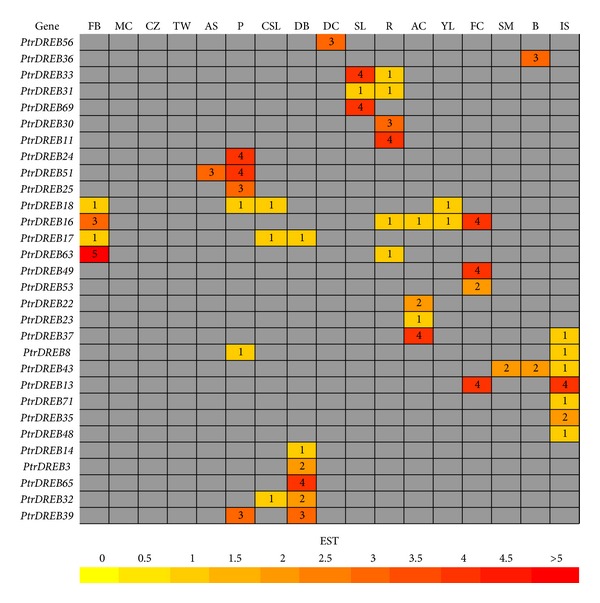

The expression profile for each gene was obtained by the Digital Northern tool, which generates a digital northern expression profile heat map based on the ESTs, and is a useful additional means of inferring gene function by examining expression patterns based on the frequency of ESTs in libraries prepared from various tissues [15] (Figure 5). Such analysis yielded 32 Populus DREB genes in the available cDNA libraries. Of the 32 DREBs examined, 16 genes in the digital expression analysis had high transcript accumulation. A comparison of the digital northern expression analysis revealed that PtrDREB16 and 63 had high transcript accumulation in flower buds, PtrDREB51 in apical shoots, PtrDREB24, 25, and 51 in petioles, PtrDREB39 and 65 in dormant buds, PtrDREB33 and 69 in senescing leaves, PtrDREB11 and 30 in roots, PtrDREB37 in active cambium, PtrDREB71 in shoot meristem, PtrDREB13, 16, and 49 in female catkins, PtrDREB36 in bark, and PtrDREB13 in imbibed seeds. On the whole, the remaining genes had low transcript accumulation in the different libraries examined. The low-abundance TFs had relatively low EST frequencies [24] and most of the DREBs were represented by only one single EST in the cDNA libraries. Nevertheless, this expression analysis demonstrated that most of the DREBs have a broad expression pattern across different tissues.

Figure 5.

In silico EST analysis of Populus DREB genes. Color bar at bottom represents the frequencies of EST counts. FB: flower buds, MC: male catkins, CZ: cambial zone, TW: tension wood, AS: apical shoot, R: roots, CSL: cold stressed leaves, DB: dormant buds, DC: dormant cambium, SL: senescing leaves, P: petioles, AC: active cambium, YL: young leaves, FC: female catkins, SM: shoot meristem, B: bark, IS: imbibed seeds. Gene names are shown on the left.

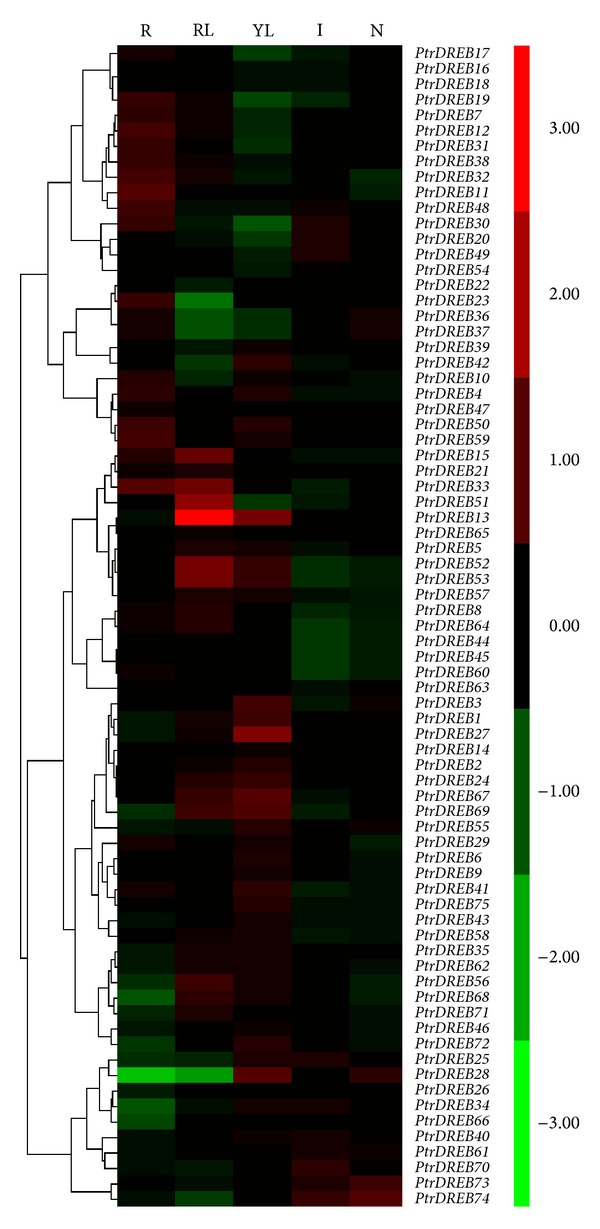

To gain more insights into the expression profiles of DREB genes, we then reanalyzed the previously published microarray data in Populus. We first investigated the global expression profiles of DREB genes by examining Affymetrix (GSE6422) [25] microarray data from Gene Expression Omnibus. Seventy-five DREB genes were included in GSE6422, and the DREB genes showed a distinct tissue-specific expression pattern (Figure 6). A comparison of the different tissues revealed that PtrDREB13, 15, 33, 51, and 53 were overrepresented, however PtrDREB23 and 28 were under-represented in mature leaves. PtrDREB13, 27, 28, 67, and 69 were over-represented, however PtrDREB30 was under-represented in young leaves. PtrDREB20, 30, 49, 70, and 74 were over-represented in internodes. PtrDREB28, 73, and 74 were over-represented in nodes. PtrDREB7, 11, and 18 were over-represented, however PtrDREB28 was under-represented in roots. On the whole, the remaining genes showed low-abundance transcription levels in the different tissues. EST profiling and microarray analysis showed that PtrDREB28, 73, 74, 37, and 71 had high-abundance transcripts in the cambium. Previous studies using genome-wide transcriptional profiling in Arabidopsis revealed that stress-related and touch-inducible genes are upregulated in stem regions where secondary growth takes place [26].

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of Populus DREB genes across different tissues. Heat map showing hierarchical clustering of 75 PtrDREB genes across various tissues analyzed. The Affymetrix microarray data were obtained from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the series accession number GSE16422. ML: mature leaf; YL: young leaf; R: root; I: internodes; N: nodes. Color scale represents log2 expression values, green represents low level, and red indicates high level of transcript abundances.

3.6. Expression of DREB Genes under Abiotic Stress Conditions in Populus

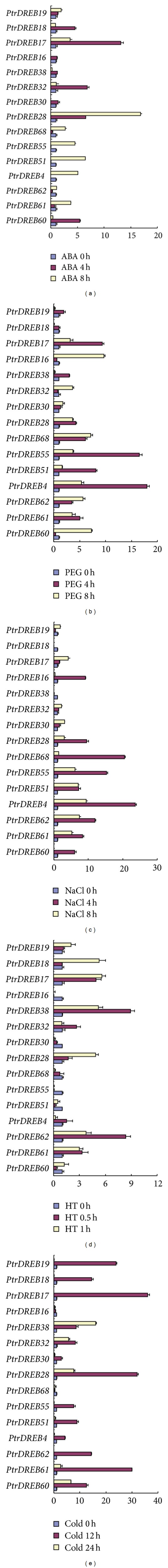

Studies have previously been conducted to evaluate the expression of the DREB Populus genes in response to stresses such as low temperature, high temperature, salt, and dehydration [7]. However, the genes that were evaluated in our study were predicted to be candidate genes in Populus via EST profiling and microarray analysis. We have quantified the expression levels of the genes in leaf tissue after exposure to different abiotic stress conditions. The results provide an abundant set of information regarding the expression of these genes in Populus in response to low temperature, high temperature, ABA, salt, and dehydration (Figure 7). Among 15 selected DREB genes, there was evidence of induced expression under different abiotic stresses conditions, with the exception of PtrDREB30.

Figure 7.

Expression analysis of fifteen selected P. trichocarpa DREB genes in mature leaves under ABA (a), drought stresses (b), salinity (c), high temperature (d), and low temperature (e) by qRT-PCR. The data were normalized using the P. trichocarpa actin gene. Standard deviations were derived from three replicates of each experiment.

PtrDREB60, 61, and 62, which belong to the A-1 subgroup, were stress-inducible by low temperature, salt, and dehydration (Figure 7). In addition, PtrDREB62 was stress-inducible by high temperature and PtrDREB60 was stress-inducible by ABA. These findings are consistent with those of Dubouzet et al. (2003), who reported the increased expression of an A-1 subgroup gene (OsDREB1) of rice [10]. It was a major regulator of cold-stress responses in the DREB1/CBF (A-1) subgroup [7]. In a recent study, they indicated that ethylene signaling plays a negative role in the adaptation of Arabidopsis to freezing stress [26]. Additionally, some studies indicated that the AmCBF2 was inducible by heavy metals (Pb2+ or Zn2+) [4].

PtrDREB4 and PtrDREB28 belong to the A-2 subgroup (Figure 7), and they were stress-inducible by ABA, salt, and dehydration. In addition, PtrDREB28 was stress-inducible by high temperature and low temperature. This finding is consistent with those of Dubouzet et al. (2003) [10], who reported increased expression of an A-2 subgroup gene (MsDREB2C) of Malus sieversii Roem [27]. It was a major regulator of dehydration and heat shock responses in the DREB2 subgroup [7]. This indicated that ethylene signaling plays a negative role in the adaptation of Arabidopsis to freezing stress [26]. The oxidative stress tolerance of DREB2C-overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis plants was regulated by heat shock factor A3 (HsfA3) and HsfA3 is regulated at the transcriptional level by DREB2 [28].

PtrDREB51, 55, and 68 belong to the A-4 subgroup, and they were stress-inducible by salt and dehydration. However, PtrDREB51, 55, and 68 were down represented by high temperature PtrDREB68 was down represented by low temperature. Genes PtrDREB30, 32, and 38 belonged to subgroup A-5. PtrDREB32 was stress-inducible by cold and ABA, whereas PtrDREB38 was induced by hot and cold temperatures. PtrDREB30 was down represented by high temperature, whereas PtrDREB38 was down represented by salt. PtrDREB16, 17, 18, and 19 belonged to the A-6 subgroup. PtrDREB16 was induced by drought and high salt, and PtrDREB17 was induced by drought, high temperature, low temperature, and ABA treatment. PtrDREB18 was induced by high temperature, low temperature, and ABA. In addition, PtrDREB19 was only induced by low temperature. PtrDREB18 was down represented by by salt, whereas PtrDREB16 was down represented by high temperature and cold temperature (Figure 7). In our study, a digital northern analysis showed that the genes PtrDREB17, 18, and 32 were expressed in cold-stressed leaves, and showed the same expression trends based on qRT-PCR. The expression patterns of Populus DREB genes detected by qRT-PCR are generally consistent with microarray analyses and digital northern analyses.

Some studies indicate that the HARDY (At2g36450) gene belongs to the A-4 subgroup. The overexpression of the HRD gene for the improvement of water-use efficiency is coincident with drought resistance in rice. The analogous genes At2g36450 and PtrDREB68 were stress-inducible in drought [29]. The homologous genes, RAP2.4 (At1g78080) and PtrDREB19 and RAP2.4B (AT1G22190) and PtrDREB17, were expressed in response to dehydration, high salinity, and heat [30, 31]. Overexpression or mutation of RAP2.4 and RAP2.4B in Arabidopsis acts at or downstream of a point of convergence for light and ethylene signaling pathways that coordinately regulates multiple developmental processes and stress responses [30]. It is noteworthy that the expression of several other genes associated with lipid transport was altered in the RAP2.4 and RAP2.4B overexpression lines, further supporting the link between DREB TFs and adaptive alterations in lipid metabolism [31]. Hence, we think that the PtrDREB16 and 17 TFs are probably associated with enhanced drought tolerance by modulating the wax biosynthetic pathway.

4. Conclusions

Understanding the plant DREB subfamily is important for elucidating the mechanisms of a variety of stress responses. Therefore, we present a comprehensive and specific analysis of gene structure, chromosome localization, and expression of the Populus DREB subfamily for the first time. We predicted P. trichocarpa DREB gene expression and function through comparisons with similar genes that have been well studied in model or other plants. The chromosomal localizations of the PtrDREB genes involved in transcription regulation and signal transduction are preferentially retained following duplications. The conserved motif composition of PtrDREB genes were highly conserved in the same subtype. EST profiling and microarray analysis of this gene subfamily from different tissues and/or developmental stages showed the same expression trends based on qRT-PCR. The results in the present study indicate that DREBs function as important transcriptional activators and may be useful in improving plant tolerance to abiotic stresses. Taken together, these observations may lay the foundation for future functional analyses of Populus DREB genes to unravel their biological roles.

Supplementary Material

Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence from selected members of the DREB family in Populus trichocarpa. Amino acids are expressed in the standard single letter code. the PtrDREB gene subfamily can be classified broadly into six subtypes (DREB A-1 to A-6) in Populus. The AP2/ERF domain consists of three β-sheet and one α-helix at the N termini. Arrows designate the highly conserved 14th valine (V14) and 19th glutamic acid (E19).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Key Project of Chinese National Programs for Fundamental Research and Development (973 Program: 2009CB119100), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2011AA100203), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DL11EA02).

References

- 1.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, et al. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 1998;10(8):1391–1406. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakuma Y, Liu Q, Dubouzet JG, Abe H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2002;290(3):998–1009. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng YL, Wang YS, Cheng H, et al. Characterization and expression analysis of three CBF/DREB1 transcriptional factor genes from mangrove Avicennia marina. Genome. 2013;140-141:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcolino-Gomes J, Rodrigues FA, Oliveira MCN, et al. Expression patterns of GmAP2/EREB-like transcription factors involved in soybean responses to water deficit. PloS One. 2013;8(5):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouaziz D, Pirrello J, Charfeddine M, et al. Overexpression of StDREB1 transcription factor increases tolerance to salt in transgenic potato plants. Molecular Biotechnology. 2013;54(3):830–817. doi: 10.1007/s12033-012-9628-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizoi J, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. AP2/ERF family transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1819(2):86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuang J, Peng R-H, Cheng Z-M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the putative AP2/ERF family genes in Vitis vinifera . Scientia Horticulturae. 2009;123(1):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharoni AM, Nuruzzaman M, Satoh K, et al. Gene structures, classification and expression models of the AP2/EREBP transcription factor family in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2011;52(2):344–360. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubouzet JG, Sakuma Y, Ito Y, et al. OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-, high-salt- and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant Journal. 2003;33(4):751–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuskan GA, Difazio SP, Teichmann T. Poplar genomics is getting popular: the impact of the poplar genome project on tree research. Plant Biology. 2004;6(1):2–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ. The jalview java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjödin A, Street NR, Sandberg G, Gustafsson P, Jansson S. The Populus Genome Integrative Explorer (PopGenIE): a new resource for exploring the Populus genome. New Phytologist. 2009;182(4):1013–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toufighi K, Brady SM, Austin R, Ly E, Provart NJ. The botany array resource: e-Northerns, expression angling, and promoter analyses. Plant Journal. 2005;43(1):153–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhuang J, Cai B, Peng R-H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;371(3):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu R, Chi X, Chai G, et al. Genome-Wide identification, evolutionary expansion, and expression profile of Homeodomain-Leucine zipper gene family in poplar (populus trichocarpa) PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031149.e31149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanc G, Wolfe KH. Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell. 2004;16(7):1679–1691. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Chen X, Liu Y, Gao H, Wang Z, Sun G. CkDREB gene in Caragana korshinskii is involved in the regulation of stress response to multiple abiotic stresses as an AP2/EREBP transcription factor. Molecular Biology Reports. 2011;38(4):2801–2811. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douglas CJ, DiFazio SP. The Populus genome and comparative genomics. In: Jansson S, Bhalerao R, Groover A, editors. Genetics and Genomics of Populus. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaglo KR, Kleff S, Amundsen KL, et al. Components of the Arabidopsis C-repeat/dehydration-responsive element binding factor cold-response pathway are conserved in Brassica napus and other plant species. Plant Physiology. 2001;127(3):910–917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano T, Suzuki K, Fujimura T, Shinshi H. Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiology. 2006;140(2):411–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkins O, Nahal H, Foong J, Provart NJ, Campbell MM. Expansion and diversification of the Populus R2R3-MYB family of transcription factors. Plant Physiology. 2009;149(2):981–993. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.132795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, Kalluri UC, Jawdy S, et al. The F-box gene family is expanded in herbaceous annual plants relative to woody perennial plants. Plant Physiology. 2008;148(3):1189–1200. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.121921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Tian S, Hou L, et al. Ethylene signaling negatively regulates freezing tolerance by repressing expression of CBF and type-A ARR genes in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell Online. 2012;24(6):2578–2595. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao K, Shen X, Yuan H, et al. Isolation and characterization of dehydration-responsive element-binding factor 2C (MsDREB2C) from malus sieversii roem. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54(8):468–471. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang JE, Lim CJ, Chen H C, Je J, Song C, Lim CO. Overexpression of arabidopsis dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2C confers tolerance to oxidative stress. Molecules and Cells. 2012;33(2):135–140. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-2188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karaba A, Dixit S, Greco R, et al. Improvement of water use efficiency in rice by expression of HARDY, an Arabidopsis drought and salt tolerance gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(39):15270–15275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707294104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin R-C, Park H-J, Wang H-Y. Role of Arabidopsis RAP2.4 in regulating light- and ethylene-mediated developmental processes and drought stress tolerance. Molecular plant. 2008;1(1):42–57. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rae L, Lao NT, Kavanagh TA. Regulation of multiple aquaporin genes in Arabidopsis by a pair of recently duplicated DREB transcription factors. Planta. 2011;234(3):429–444. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence from selected members of the DREB family in Populus trichocarpa. Amino acids are expressed in the standard single letter code. the PtrDREB gene subfamily can be classified broadly into six subtypes (DREB A-1 to A-6) in Populus. The AP2/ERF domain consists of three β-sheet and one α-helix at the N termini. Arrows designate the highly conserved 14th valine (V14) and 19th glutamic acid (E19).