Abstract

Giant cells are the soldiers of defensive system of our body. They differ based on the stimuli that provoked their formation. On the other hand, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) being the most common oral cancer, presents with varied histopathological features based on the degree of differentiation. Keratinizing islands of dysplastic squamous epithelial cells & a dense inflammatory response form the major component of well differentiated SCC. This keratin component may sometimes trigger foreign body giant cell (FBGC) reaction in the stroma, which may mislead the pathologist to aggressive forms of SCC containing pleomorphic giant cells. We encountered such an interesting case of foreign body giant cell reaction in oral SCC. Thus, the present article aims to provide a thorough knowledge on FBGC including their appearance, pathogenesis & significance in oral SCC.

How to cite this article: Patil S, Rao RS, Ganavi BS. A Foreigner in Squamous Cell Carcinoma!. J Int Oral Health 2013;5(5):147-50.

Key Words: : Squamous cell carcinoma, foreign body giant cells, keratin pearls

Introduction

Cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage can fuse to form multinucleated giant cells which enhance their defensive capacities in various pathologic conditions. The phenotype of these giant cells varies depending on the local environment and the chemical and physical (size) nature of the stimulus that provoked their formation.1,2

Oral cancers often present as squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), accounting for more than 90%.3,4 Most oral SCCs histo-pathologically present either as moderately or well-differentiated lesions with increase in keratin pearls & individual cell keratinization.5 Occurrence of giant cells in oral SCC is a noteworthy phenomenon.

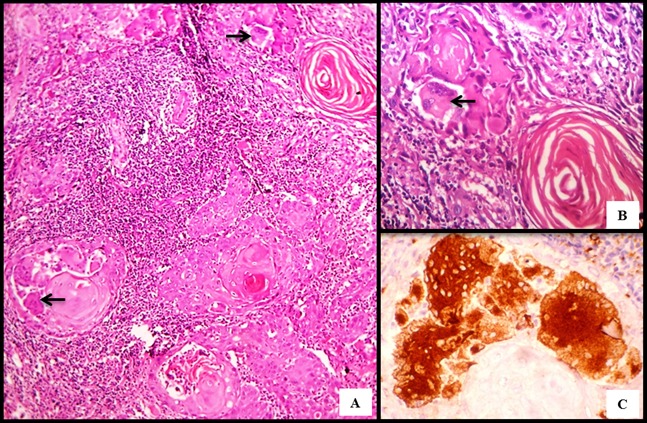

A biopsy of untreated case of oral cancer was referred to our department. It was histopathologically diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC. An unusual presentation of multinucleated giant cells were encountered in the stroma. The giant cells were found in focal aggregates in close association with keratinizing tumor cells, keratin pearls & free keratin debris (Figure 1). The cytoplasm of individual cell was intensely eosinophilic with vacuoles & nuclei appeared uniformly small & regularly dispersed. Incidentally, the cells lacked nuclear atypia/mitosis. Hence, these benign multinucleated cells could be categorised as foreign body type. In addition, they were accompanied by a dense chronic inflammatory response predominated by lymphocytes.

Fig. 1: Photomicrographs of well differentiated oral SCC eliciting FBGC reaction.

A- FBGCs abutting the keratinizing neoplastic cells (H & E, 10 X)

B- A focus of FBGCs adjacent to a keratin pearl (H & E, 40 X)

C- Immunohistochemistry demonstrating CD 68 positivity in FBGCs (IHC, 40 X)

Foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) are the hallmark of chronic inflammation that function to eliminate endogenous & exogenous foreign material from our body.6,7 Endogenous materials chiefly consist of mucin & keratin whereas, dental implants are the most frequently encountered exogenous materials. Based on the type & location of foreign material, these cells act by rejection, dissolution, resorption or fibrous encapsulation.7

Keratin, an epithelial derived protein is known to provoke giant cell reaction in stroma. Keratin induced foreign body giant cell reactions are reported in malignant epidermoid tumors, calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, ruptured epidermal inclusion cyst & pilomatrixoma.7,8

In particular, identification of foreign body giant cells in SCC dates back to 1900 when Cullen described them in cervical carcinoma.9 Later several authors described them in SCC of various sites including oral cavity & more frequently in SCCs treated by radiotherapy.8,10 These giant cells tend to locate in the vicinity of devitalized and keratinized tumor tissue & are believed to serve a resorptive function. Moreover, areas of extensive keratinization demonstrated large keratin granulomas.8

Two different concepts on foreign body giant cell formation were proposed:

Mononuclear cells undergo amitotic division, resulting in a multinucleated giant cell.

Fusion of mononuclear cells forming a multinucleated giant cell.

Further, studies by Silverman and Shorter, Mitchell V. Kaminski and Patrick D. Toto proved that the foreign body giant cells result from the fusion of mononuclear cells.11,12 Electron microscopic and enzyme-histochemical studies on FBGCs in SCC by Burkhardt et al also favoured the latter concept of origin from macrophages.13 Our case also demonstrated CD 68 positivity reiterating the histiocytic origin.

In SCC, keratin liberated into the stroma is considered foreign & this results in induction of granulomatous inflammation with generation of FBGCs. This may be also associated with lymphocytes, plasma cells & limited by fibrous tissue.7

As mentioned earlier, several authors: Renault et al. (1972), Iversen(1974), Hornovg and Bilder(1974), Berdal et al. (1975), Burkhardt and Holtje (1975) & Burkhardt et al. (1976a) have encountered such giant cells during cancer therapy.13 This is in contrast with our untreated case.

Numerous studies on histopathological changes associated with irradiated SCC have shown significant

number of FBGCs. Homa Safaii & Henrya Azar noted few or no FBGCs in pre-irradiation biopsies as compared to post-irradiation samples which revealed extensive keratinization surrounded by numerous FBGCs.This may be due to chemical inertness & chemotactic effects of disulphide groups of keratin released into stroma by irradiation.8

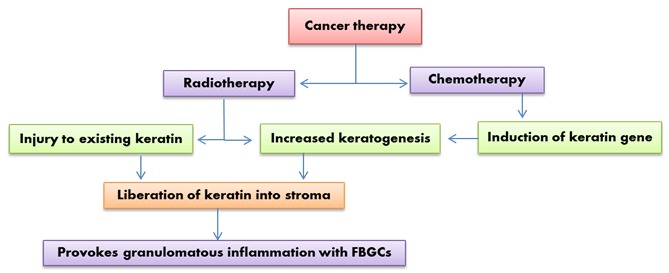

During chemotherapy, maturation of tumor cells with increased keratinization & concomitant FBGC reaction is noted.13,14 The possible hypotheses on FBGC generation during cancer therapy is summarized in flowchart 1.

Flowchart 1: Possible hypotheses on FBGC generation during treatment of SCC8, 13,14.

Formation of FBGCs in SCC is a simple defensive mechanism against keratins spilled into the stroma. On the contrary, post-therapeutic keratogenesis may be assumed as an attempt of tumor cells to survive under adverse conditions.8 Despite extensive research, the impact of FBGCs on the SCC prognosis is still unclear. Most authors believe that the prognosis in such cases remains unaltered.

A word of caution is to be borne in mind as giant cells may be associated with oral carcinomas namely, spindle cell carcinoma & giant cell carcinoma. Spindle cell SCC, a rare poorly differentiated variant of SCC frequently demonstrates bizarre, pleomorphic giant cells.15,16 On the other hand, giant cell carcinoma is an infrequent pathological subtype of OSCC, more common in lung, larynx, etc. The term giant cell carcinoma is applied only when malignant giant cells form the major component of a carcinoma.17,18 Both these entities display worse prognosis when compared to SCC with FBGCs.16,17,18

Although the significance of FBGCs in oral SCC is unclear, pathologists must be aware of such a benign component & carefully tread before concluding the diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None Declared

Contributor Information

Shankargouda Patil, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, M S Ramaiah Dental College & Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Roopa S Rao, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, M S Ramaiah Dental College & Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

B S Ganavi, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, M S Ramaiah Dental College & Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

References

- 1.WG Brodbeck, JM Anderson. Giant cell formation and function. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(1):53–57. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32831ac52e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.S MacLauchlan, EA Skokos, N Meznarich, DH Zhu, S Raoof, JM Shipley, et al. Macrophage fusion, giant cell formation, and the foreign body response require matrix metalloproteinase 9. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(4):617–626. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1008588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.C Scully, JV Bagan, C Hopper, JB Epstein. Oral cancer: Current and future diagnostic techniques. Am J Dent. 2008;21:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BW Neville, TA Day. Oral Cancer and Precancerous Lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(4):195–215. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.JA Regezi, JJ Sciubba, RC Jordan. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic correlations, 5th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders. 2008:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.AT Tsai, J Rice, M Scatena, L Liaw, BD Ratner, CM Giachelli. The role of osteopontin in foreign body giant cell formation. Biomaterials. 2005;26(29):5835–5843. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.K Donath, M Laass, HJ Gunzl. The histopathology of different foreign-body reactions in oral soft tissue and bone tissue. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420(2):131–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02358804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.H Safall, HA Azar. Keratin granulomas in irradiated squamous cell carcinoma of various sites. Cancer Res. 1966;26(3):500–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TS Cullen. Cancer of Uterus, Its Pathology and Symptomatology, Diagnosis and Treatment also The Pathology of diseases of the Endometrium. New York: D. Appleton and Co. 1900:97–98. [Google Scholar]

- 10.A Carlile, C Edwards. Poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma of the bronchus: A light & electron microscopic study. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39(3):284–292. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.3.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.L Silverman, RG Shorter. Histogenesis of the Multinucleated Giant Cell. Lab Invest. 1963;12:985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MV Kaminski, PD Toto. Histogenesis of Foreign Body Giant Cells. J Dent Res. 1967;46(1):245–247. doi: 10.1177/00220345670460011801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A Burkhardt, JO Gebbers. Giant Cell Stromal Reaction in Squamous Cell Carcinomata. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1977;375(4):263–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00427058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.T Moore, AY Moore, M Langer, Jr Wagner RF. Tumor Remnants within Giant Cells following Irradiation of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(10):1094–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.EB Stelow, SE Mills. Squamous Cell Carcinoma Variants of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124(Suppl):96–109. doi: 10.1309/CR5JXUY3J2YGTC1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MH Rinker, NA Fenske, LA Scalf, LF Glass. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Control. 2001;8(4):354–363. doi: 10.1177/107327480100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.S Warnakulasuriya, WM Tilakaratne. Oral Medicine & Pathology: A guide to Diagnosis & Management, 1st ed. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2014:324. [Google Scholar]

- 18.NF Fishback, WD Travis, CA Moran, Jr Guinee DG, WF McCarthy, MN Koss. Pleomorphic (spindle/giant cell) carcinoma of the lung. A clinicopathologic correlation of 78 cases. Cancer. 1994;73(12):2936–2945. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940615)73:12<2936::aid-cncr2820731210>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]