Abstract

Aims

Glycopyrronium bromide (NVA237) is a once-daily long-acting muscarinic antagonist recently approved for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In this study, we used population pharmacokinetic (PK) modelling to provide insights into the impact of the lung PK of glycopyrronium on its systemic PK profile and, in turn, to understand the impact of lung bioavailability and residence time on the choice of dosage regimen.

Methods

We developed and validated a population PK model to characterize the lung absorption of glycopyrronium using plasma PK data derived from studies in which this drug was administered by different routes to healthy volunteers. The model was also used to carry out simulations of once-daily and twice-daily regimens and to characterize amounts of glycopyrronium in systemic compartments and lungs.

Results

The model-derived PK parameters were comparable to those obtained with noncompartmental analysis, confirming the usefulness of our model. The model suggested that the lung absorption of glycopyrronium was dominated by slow-phase absorption with a half-life of about 3.5 days, which accounted for 79% of drug absorbed through the lungs into the bloodstream, from where glycopyrronium was quickly eliminated. Simulations of once-daily and twice-daily administration generated similar PK profiles in the lung compartments.

Conclusions

The slow absorption from the lungs, together with the rapid elimination from the systemic circulation, could explain how once-daily glycopyrronium provides sustained bronchodilatation with a low incidence of adverse effects in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Its extended intrapulmonary residence time also provides pharmacokinetic evidence that glycopyrronium has the profile of a once-daily drug.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, glycopyrronium, lung absorption, modelling, pharmacokinetics

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Steady- state trough plasma levels of the new long-acting muscarinic antagonist glycopyrronium following once-daily inhalation are on average about 5% of the peak levels. Concentrations at the site of action, i.e. the lungs, are not known.

Lung absorption studies support the selection of an optimal dosing regimen of inhaled drugs.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

A population pharmacokinetic model was used to characterize the lung absorption and disposition of glycopyrronium.

The study has shown that glycopyrronium is slowly absorbed from the lungs and has the profile of a once-daily drug.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a preventable and treatable lung disease characterized by progressive airflow limitation. Bronchodilators are the mainstay of pharmacological therapy for COPD [1]. As the inhaled route delivers high local concentrations of drug at the target site with low systemic exposure [2, 3], inhalation of bronchodilators is preferred over oral dosing in COPD [1]. Long-acting inhaled bronchodilators are the recommended first-line maintenance treatment for COPD [1]. Treatment options include long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) and long-acting β2-agonists. Glycopyrronium bromide (NVA237) is an inhaled once-daily LAMA recently approved for the treatment of COPD. Glycopyrronium is delivered by a single-dose, dry-powder inhaler, which was specifically developed to have a low internal resistance and therefore ensure efficient drug delivery in patients with a wide range of COPD severities, including severe COPD [4].

Glycopyrronium, the quaternary ammonium ion of glycopyrronium bromide, acts as a competitive antagonist by binding to the muscarinic receptors in the bronchial smooth musculature, thereby preventing acetylcholine-induced bronchoconstriction [5]. Phase II and III clinical trials have shown that once-daily glycopyrronium produces rapid and sustained 24 h bronchodilatation in patients with COPD, and has an acceptable safety and tolerability profile [6–10].

As the characterization of lung deposition efficiency and absorption properties could support the selection of the optimal dosage regimen and dosing interval of new inhaled drugs, in this study we investigated the lung pharmacokinetics (PK) of glycopyrronium. In order to overcome the complexity and limitations of studying lung pharmacokinetics in isolated, perfused lung experiments [11], we used a population PK model to characterize the lung absorption and disposition of glycopyrronium in humans. The model was used to determine the PK profile of inhaled glycopyrronium with respect to the fractions of absorbed drug going through the lung compartments and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and to simulate the amount of drug in the lung and systemic compartments following once-daily and twice-daily administration. The ultimate aim of this analysis was to provide insights into the impact of the lung PK of glycopyrronium on its systemic PK profile and, in turn, to understand the impact of lung bioavailability and residence time on the choice of dosage regimen.

Materials and methods

Two studies in healthy volunteers provided data for the model development and validation. Doses and concentrations of glycopyrronium reported in these studies refer to the pharmacologically active moiety of glycopyrronium bromide. Study 1 investigated the absolute bioavailability of inhaled glycopyrronium and compared the PK, safety and tolerability of single inhaled doses with other routes of administration [12]. The study had two parts. Part 1 compared single oral doses of 400 μg glycopyrronium given with and without oral activated charcoal, which was shown to be effective in blocking the absorption of glycopyrronium from the gastrointestinal tract [12]. Part 2 compared the PK of inhaled glycopyrronium 200 μg concomitantly with and without oral activated charcoal with that of an intravenous (i.v.) dose of 120 μg glycopyrronium given as a 5 min infusion. Study 2 was a four-period crossover study comparing the PK of a fixed dose combination of glycopyrronium and indacaterol with that of the individual drugs as well as the free combination of the two drugs. Each treatment consisted of 14 once-daily doses of the respective individual drug or combination (Novartis, data on file).

The studies were approved by the Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board at each centre.

Data for model development

Only Part 2 of Study 1 was used for model development. Plasma concentrations of glycopyrronium were available up to 72 h postdose from 20 healthy volunteers after i.v. administration of glycopyrronium 120 μg and from 18 healthy volunteers after inhalation of glycopyrronium 200 μg delivered by the Breezhaler® device (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) with or without concomitant administration of charcoal. The i.v. administration provided reference information on the systemic distribution and elimination profile of the drug. All available plasma concentration data were included for model building; covariates were not considered. The final model was run again, excluding the data after inhalation with charcoal for one subject who did not receive all doses of charcoal.

Data for model validation

Parts 1 and 2 of Study 1 were used for model validation. Pharmacokinetic parameters of glycopyrronium were obtained by noncompartmental methods, in Part 1 from eight subjects after oral administration of glycopyrronium and in Part 2 from 17 or 18 subjects after i.v. administration and inhalation with or without oral charcoal. These PK parameters were compared with model-predicted parameters obtained from simulations of plasma concentrations profiles in the respective conditions. From Study 2, the glycopyrronium treatment was used for model assessment. Once-daily doses of glycopyrronium 50 μg (50 μg refers to the quantity of the glycopyrronium moiety present in the capsule, which corresponds to a delivered dose of 44 μg) were inhaled via the Breezhaler® device for 14 days. Steady-state (day 14) PK parameters of glycopyrronium, determined by noncompartmental methods, were available for 24 subjects and were compared with the model-predicted steady-state parameters.

Model development

The model components include a structural model, which accounts for the systematic trends in the data and provides a mechanism for generating those trends, and a random-effects model, which accounts for variability around those trends. Model building was performed using the first-order conditional estimation with interaction method. The analysis was performed to estimate the population parameters (mean and between-subject variability) using the nonlinear mixed effects modelling (NONMEM) software system, NONMEM VI version 2, extended (Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA), the NM-TRAN subroutines version III, level 1.1, and the PREDPP model library version V, level 1.0 [13]. Some of the model diagnostics, including the visual predictive checks and run management, were done with Perl-speaks-NONMEM, version 3.5.3 [14].

The modelling approach for lung absorption adopted may be referred to as deconvolution by parametric convolution. This approach comprises the following steps.

Determine the best model that describes the PK disposition based on the i.v. reference data.

Assume that the i.v. model describes the PK disposition of the inhaled data and that the difference is due only to the input functions, which characterize bioavailability and release from the lung and the GI tract into the systemic circulation.

Add the PK data following inhalation with charcoal (which blocks GI absorption) to the data following i.v. administration and determine the best input function that fits the plasma PK profile following absorption via the lungs, given the i.v. model.

Assume that the only difference between the PK data following inhalation with charcoal and without charcoal is the absorption through the GI tract.

Add the PK data following inhalation without charcoal to the data sets in step 3 and determine the best input function for absorption through the GI tract that fits the PK profile for this mode of administration, given the models for i.v. administration and inhalation with charcoal.

All data may be analysed together to determine the best overall fit once good starting parameters have been defined.

The overall data are described by the convolution of the disposition model (uniquely identified by the i.v. data), the lung input model (uniquely identified by the inhaled data with charcoal) and the oral input model (uniquely identified by the addition of the inhaled data without activated charcoal).

Structural model

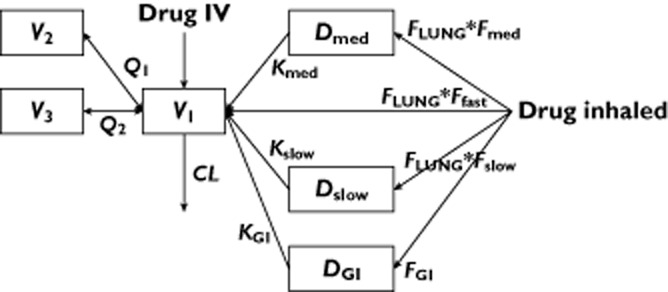

Disposition (i.e. distribution and elimination) kinetics were described with a three-compartment PK model (compartments V1–V3; Figure 1). Plasma drug concentrations are measured in compartment V1, which is referred to as the systemic circulation; compartments V2 and V3 are in slow equilibrium distribution with V1; the sum of compartments V1–V3 is referred to as the systemic compartments. Drug infusion by i.v. administration was described as zero-order infusion into compartment V1, with the infusion rate taken from the data set. Absorption of inhaled drug was described by up to four components with associated bioavailabilities and rate constants: fast, intermediate and slow lung absorption, and absorption through the GI tract. Initial absorption after inhalation was fast with glycopyrronium, and the highest plasma concentration occurred at the first measured time point at 5 min after inhalation. Therefore, there was insufficient information to fit the rate of the initial fast absorption, which was modelled as a bolus to the central PK compartment V1. Intermediate and slow lung absorptions were modelled as first-order absorption processes from intermediate (Dmed) and slow (Dslow) lung absorption compartments. Absorption through the GI tract was modelled as a first-order absorption process from the GI tract absorption compartment (DGI).

Figure 1.

Conceptual representation of the structural model. CL, systemic clearance; DGI, gastrointestinal tract absorption compartment; Dmed, intermediate lung absorption compartment; Dslow, slow lung absorption compartment; FLUNG, bioavailability after inhalation with concomitant charcoal treatment compared with i.v.; Ffast, Fmed, Fslow, relative contributions of the three different lung absorption processes to total lung absorption; FGI, fraction of the dose absorbed through gastrointestinal tract; i.v., intravenous; KGI, Kmed, Kslow, absorption rates from the different absorption compartments; V1, central plasma compartment; V2, V3, peripheral pharmacokinetic compartments; Q1, Q2 intercompartmental clearances

Parameterization of the absorption of the inhaled drug

The absolute bioavailability of inhalation with concomitant charcoal treatment compared with i.v., which is equivalent to the fraction of the inhaled dose that enters the three lung absorption compartments (FLUNG) and the relative contributions of fast, slow and intermediate lung absorption processes (Ffast, Fmed and Fslow) were parameterized in function of the odds of the absolute bioavailability with concomitant charcoal treatment (BIO) and of the relative contribution to the intermediate and slow lung absorption processes (Rmed and Rslow). The parameterization was chosen to ensure that the absolute bioavailability is constrained to be between zero and one, and that the relative contributions of the different lung absorption processes sum up to one. This parameterization resulted in the following definitions used in the models.

Bioavailability after inhalation with concomitant charcoal treatment compared with i.v.:

| (1) |

The relative contributions of the different lung absorption processes:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

As Ffast, Fmed and Fslow sum up to one, the scaling factor, FS, must be defined as:

| (5) |

The fractions of the dose that go into the different compartments that model absorption from the lung are the product of Ffast, Fmed and Fslow multiplied by FLUNG (Figure 1).

The fraction, FGI, of the dose that enters the compartment DGI that models absorption through the GI tract was parameterized as a function of the inferred absolute oral bioavailability (FORAL) according to:

| (6) |

Inferring the oral bioavailability according to equation (6) assumes that all drug that is not absorbed into the systemic circulation through the lungs (1 – FLUNG) reaches the GI tract, and that a fraction (FORAL) of the swallowed drug gets absorbed from the GI tract into the systemic circulation.

It is useful to note that the absolute bioavailability (vs. i.v. administration) after inhalation without concomitant charcoal treatment (FTOT) is given by:

| (7) |

and the relative contributions of the lung and GI tract absorption are:

| (8) |

and

| (9) |

respectively.

Random-effects model

Between-subject variability was considered in all parameters describing systemic distribution and elimination. Variability was modelled using multiplicative exponential random effects and reported as standard deviations (SD). Between-occasion/within-subject variability was considered for lung absorption parameters, modelled using multiplicative exponential random effects and reported as SD. If any of the considered variability estimates approached zero during the fit, it was fixed to zero in the subsequent run. Changing interoccasion variability into between-subject variability was considered, and was retained if it resulted in model improvement. Log-transformed data were modelled with an additive residual error model and reported as SD.

Decision criteria

Model adequacy was evaluated using the following criteria: change in the objective function; visual inspection of different diagnostic plots; precision of the parameter estimates; and decreases in between-subject variability, between-occasion variability and residual variability.

At all stages of model development, diagnostic plots were examined to assess model adequacy, possible lack of fit or violation of assumptions. Plots of observed values vs. predicted values and observed values vs. individual predicted values were evaluated for randomness around the line of unity. Plots of weighted residual vs. time were evaluated for randomness around the zero line. These diagnostic plots were stratified by regimen to ensure adequacy of the fit across these design factors. Once a stable full model was obtained, box plots of the etas (maximum a posteriori Bayesian post hoc estimates of the between-subject and between-occasion/within-subject random effects) vs. regimen were also generated to evaluate regimen invariance.

Simulation methodology

Pharmacokinetic parameters were obtained from the final model, accounting for intersubject variability, interoccasion variability and uncertainty in parameter estimate [15]. Intersubject variability differentiated the subjects from each simulated trial; to account for uncertainty in parameter estimates, each trial was simulated repeatedly. The presented results were obtained from 50 repeated trials with 50 subjects each. The median values over the trials were reported for the means and SDs calculated for selected properties [e.g. area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) and maximal plasma concentration (Cmax)] of each trial. For each simulated parameter vector, which represented a simulated individual, concentrations were calculated. For comparison with Study 1, simulations for a single 5 min i.v. infusion of 120 μg glycopyrronium, single inhalations of 200 μg glycopyrronium with and without concomitant administration of charcoal, and a single oral dose of 400 μg glycopyrronium were performed. For comparison with Study 2 and for comparing once-daily and twice-daily regimens, multiple-dose treatments (14 days) were simulated with inhalation of either glycopyrronium 50 μg once daily or glycopyrronium 25 μg twice daily. In the simulation to be compared with Study 1, concentrations were calculated at the scheduled PK sampling time points from the study to 72 h postdose. In the simulation of the multiple-dose treatments, concentrations were calculated in all 12 h intervals of 14 days at 0, 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 11.99 h; this is a compromise between having the same sampling times as in Study 2 and having the same sampling times for the two daily administrations in a twice-daily regimen. Area under the curve values for comparison with the values reported in the studies were calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The modelling used the assumption/simplification that fast absorption after inhalation occurs immediately, which leads to nonzero concentrations at 0 h after dosing. This is incompatible with the noncompartmental analysis of the study, which uses the predose concentration of zero together with the trapezoidal rule [12]. In order to assess this difference, AUC values were also calculated after setting the concentration at 0 h after dosing to zero. Maximal concentration values for comparison with the studies were calculated excluding the time point at 0 h after dosing.

Nomenclature used in the manuscript

The nomenclature used for the molecular target of glycopyrronium (muscarinic receptors) conforms to British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels [16].

Results

Description of the observed data

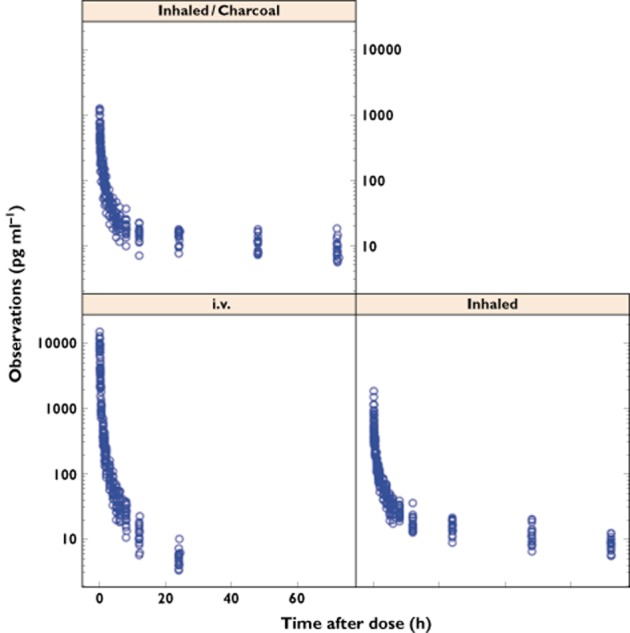

The data available for model building are summarized in Table 1. The plasma concentration–time profiles for i.v. glycopyrronium and inhaled glycopyrronium with or without charcoal are represented in Figure 2. With i.v. administration, the concentration decreased more rapidly than with inhalation and was below the lower limit of quantification at time points later than 24 h in all subjects. In contrast, after inhalation with or without charcoal all subjects had measurable plasma concentrations of glycopyrronium up to 72 h postdose. The terminal elimination phase was longer after glycopyrronium inhalation without or with charcoal [half-life (t1/2) = 52.5 and 57.2 h, respectively] than after i.v. dosing (t1/2 = 6.2 h) [12]. Thus, absorption of inhaled drug is characterized by a process notably slower than the systemic elimination half-life.

Table 1.

Data (Study 1) used for model building

| Treatment arm | Dose (μg) | Number of subjects with data | Number of data points above limit of quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous | 120 | 20 | 277 |

| Inhaled | 200 | 18 | 288 |

| Inhaled + activated charcoal | 200 | 17 | 272 |

Figure 2.

Study 1 plasma concentration data (logarithmic scale) of glycopyrronium after intravenous administration and inhaled with or without charcoal. i.v., intravenous

Final model description

The final model corresponded to the structural model, with variability added to all terms for which this was possible. For example, when fitting the model and including variability on all terms, the between-subject variability term of the volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment V2 approached zero. Fixing this variability term to zero gave the final model. Variability of the parameter describing lung bioavailability (BIO) was modelled as between-subject variability, which resulted in a slightly improved objective function compared with the models with interoccasion/within-subject variability on BIO.

A four-compartment PK model was considered during model building. Without variability on parameters, the four-compartment model was better than the three-compartment model, as judged by a difference in the objective function of 100. However, resulting parameters were of limited precision, the covariance and minimization steps tended to fail when variability was included, and the best model obtained with the four-compartment model was inferior in terms of objective function than the final three-compartment model.

Final model: parameter estimates

Population mean parameters were identified with high precision (Table 2). Variability terms were, in general, rather small and were estimated with limited precision. The largest variability was identified for parameters related to absorption, e.g. bioavailability after inhalation with concomitant charcoal treatment (related to BIO), inferred absolute oral bioavailability (FORAL), the intermediate lung absorption rate (Kmed) and the relative contributions of the three different lung absorption processes (related to Rslow and Rmed).

Table 2.

Fitted parameters in the final model

| Parameter | Abbreviation | Units | Population mean (%CV) | Variability* SD (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic clearance | CL | l h−1 | 44.9 (3.1) | 0.139 (26.4) |

| Volume of central plasma compartment | V1 | l | 11.3 (6.7) | 0.147 (93.1) |

| Intercompartmental clearance | Q1 | l h−1 | 25.6 (8.9) | 0.172 (128) |

| Volume of peripheral PK compartment | V2 | l | 19 (4.4) | 0 (fixed) |

| Intercompartmental clearance | Q2 | l h−1 | 8.23 (6.4) | 0.184 (60.6) |

| Volume of peripheral PK compartment | V3 | l | 71.5 (6.8) | 0.165 (56.1) |

| Bioavailability after inhalation with concomitant charcoal treatment expressed as odds | BIO | – | 1.11 (18) | 0.452 (56.9) |

| Parameter related to fraction of dose with slow absorption | Rslow | – | 6.48 (8.1) | 0.231 (29.8) |

| Parameter related to fraction of dose with intermediate absorption | Rmed | – | 0.734 (16.8) | 0.355 (55.1) |

| Inferred absolute oral bioavailability | FORAL | – | 0.082 (15.2) | 0.329 (53.9) |

| Slow lung absorption rate | Kslow | h−1 | 0.009 (10.1) | 0.178 (57.6) |

| Intermediate lung absorption rate | Kmed | h−1 | 1.54 (20.9) | 0.455 (93.2) |

| GI tract absorption rate | KGI | h−1 | 0.34 (8.2) | 0.14 (138.1) |

| Residual error (SD) | – | – | 0.148 (3.5) | – |

Estimates were obtained by fitting the model to the plasma profiles. Provided values are population estimates (%CV).

Reported variabilities are unitless standard deviations of multiplicative exponential random effects. CV, coefficient of variation; GI, gastrointestinal; PK, pharmacokinetic.

Model validation

The performance of the model in predicting the PK profile of glycopyrronium was assessed by comparing results obtained from simulation of a single dose performed in the conditions previously described for Study 1, with the real data obtained from the study (Table 3). In order to assess the quality of the model further, the results obtained from a simulation of repeated once-daily dosing performed in the conditions previously described for the glycopyrronium treatment of Study 2 were compared with the real outcome of the study (Table 4). As illustrated in Tables 3 and 4, the good overall agreement between the predicted parameters and the data obtained in the studies suggests that the model was able to predict the PK profile of glycopyrronium.

Table 3.

Simulation of Study 1

| Parameter | Abbreviation | Units | Intravenous glycopyrronium | Inhaled glycopyrronium | Inhaled glycopyrronium + activated charcoal | Oral glycopyrronium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | – | μg | 120 | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| Maximal concentration, study report | Cmax | pg ml−1 | 9720 (2230) [n = 18] | 858 (391) [n = 18] | 729 (297) [n = 17] | 78.8 (32.7) [n = 8] |

| Maximal concentration, predicted | Cmax | pg ml−1 | 8090 (1930) | 764 (465) | 761 (476) | 94 (86) |

| Area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration, study report* | AUC0–last | h pg ml−1 | 2840 (450) [n = 18] | 1540 (259) [n = 18] | 1360 (309) [n = 17] | 432 (195) [n = 8] |

| Area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 72 h, predicted | AUC0–72 h | h pg ml−1 | 2910 (887) | 1710 (887) | 1460 (786) | 529 (528) |

| Area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 72 h, predicted† | AUC0–72 h | h pg ml−1 | – | 1660 (862) | 1410 (781) | – |

| Plasma concentration 24 h after inhalation, study report | C24 h | pg ml−1 | 4.4 (2.4) [n = 20] | 15.6 (3.5) [n = 18] | 13.7 (3.1) [n = 17] | 0.54 (1.5) [n = 8] |

| Plasma concentration 24 h after inhalation, predicted | C24 h | pg ml−1 | 4.8 (3.7) | 14.9 (8.7) | 14.1 (8.4) | 1.3 (1.9) |

In general, 24 h for i.v. dose, 72 h for inhaled doses and 8–24 h for oral dose.

Calculated by setting concentration at first time point to zero. Data from the study report are arithmetic means (SD) of individual noncompartmental values [n], while predicted data are medians of arithmetic means and SD from simulations with 50 repeated trials and 50 subjects each. i.v., intravenous.

Table 4.

Simulation of Study 2

| Parameter | Abbreviation | Units | Predicted | Study report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal concentration at steady state | Cmax,ss | pg ml−1 | 216 (129) | 216 (148) [n = 24] |

| Area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 24 h at steady state | AUC0–24 h,ss | h pg ml−1 | 653 (328) | 558 (228) [n = 24] |

| Minimal concentration at steady state | Cmin,ss | pg ml−1 | 16.9 (9.24) | 14.9 (5.24) [n = 24] |

In Study 2, glycopyrronium 50 μg was administered once daily for 14 days. Data from the study report are arithmetic means (SD) of individual noncompartmental values [n], while predicted data are medians of arithmetic means and SD from simulations with 50 repeated trials and 50 subjects each.

For the simulation of Study 1, the predicted variability was larger than the observed variability, except for Cmax after the i.v. dose; the predicted Cmax after the i.v. dose and inhalation without charcoal was smaller than the observed one by approximately 15 and 10%, respectively, and the predicted AUCs of the inhaled treatments were larger by approximately 10%. Setting the concentration at time zero to zero, which accounts for differences in how the model and the noncompartmental analysis approximate the concentration profile up to the first measured concentration, reduced the difference between the AUC values to about 5%. Table 3 also provides a comparison of a simulated oral treatment with the results from the study. The simulated AUC and Cmax values were about 25% higher than the one derived from the study.

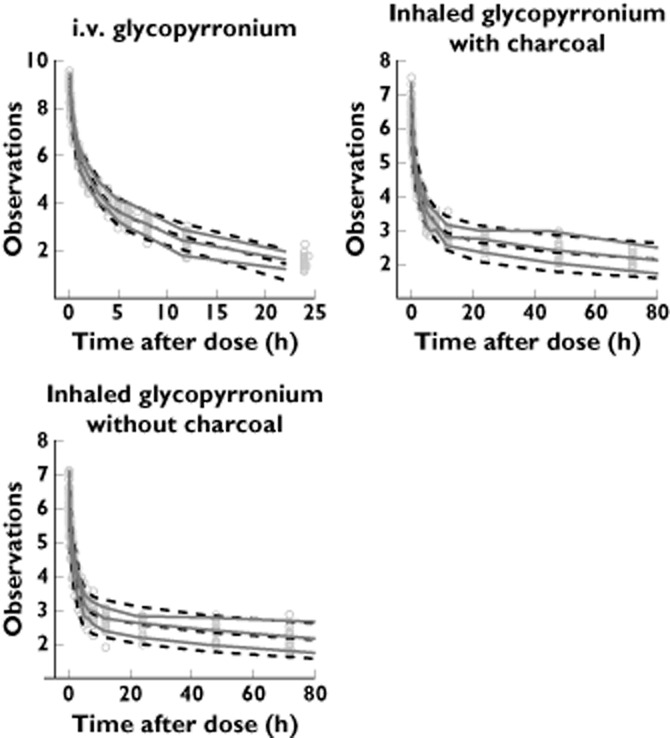

For the simulation of Study 2, agreement between PK measures obtained from the simulations and the study was comparable with that in Study 1. Notably, the predicted minimal concentration at steady state (Cmin,ss) derived from the simulation of Study 2 was in good agreement with the real data obtained in the study. This shows that systemic accumulation is adequately described by the model. A visual predictive check was also performed in order to validate the model further. This indicated that both average trends and variability are described adequately, with the median line, fifth and 95th percentiles of the data being close to the corresponding prediction intervals (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Visual predictive check. ‘Observations’ refers to the natural logarithm of the plasma concentrations of glycopyrronium (in picograms per millilitre). Time after dose is given in hours. Grey dots represent measured concentrations, continuous lines the 90% percentiles of the real data, and dashed lines the 90% prediction intervals

A further assessment of the model was performed by comparing parameters derived from the model with those obtained from noncompartmental analysis of the same data in Study 1 (Table 5). There was good agreement between both methods for the systemic clearance, the volume of distribution at steady state and the fractions of absorbed drug going through lung and GI tract, respectively. Apparent differences in absolute bioavailability, terminal half-life and oral bioavailability are addressed in the Discussion section.

Table 5.

Derived parameters for glycopyrronium

| Parameter | Abbreviation | Units | Model-based analysis* | Noncompartmental analysis† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic clearance | CL | l h−1 | 44.9 | 42.5 |

| Volume of distribution at steady state‡ | Vss | l | 102 | 82.7 |

| Ratio Vss/CL | – | h | 2.3 | 1.95 |

| Absolute bioavailability inhaled without charcoal vs. i.v. | FTOT | – | 56.5% | 40% |

| Fraction of dose absorbed through GI tract | FGI | – | 3.9% | – |

| Fraction of absorbed drug going through lung | FRLUNG | – | 93.1% | 90% |

| Fraction of absorbed drug going through GI tract | FRGI | – | 6.9% | 10% |

| Fraction of lung absorption via fast rate | Ffast | – | 12% | – |

| Fraction of lung absorption via intermediate rate | Fmed | – | 9% | – |

| Fraction of lung absorption via slow rate | Fslow | – | 79% | – |

| Fast lung absorption half-life | t1/2fast | h | <∼0.03 (estimate) | – |

| Intermediate lung absorption half-life | t1/2med | h | 0.45 | – |

| Slow lung absorption half-life | t1/2slow | h | 80 | 52 or 57§ |

| Inferred absolute oral bioavailability | FORAL | – | 8.2% | 5% |

| GI tract absorption half-life | t1/2GI | h | 2 | – |

Parameters of the population PK model (Table 2), or calculated from the population PK model parameters, with rate constants, K, expressed as half-lives, t1/2 = ln(2)/K.

From Novartis, data on file (CL, Vss) or Sechaud et al. [12].

V1 + V2 + V3.

Terminal half-lives estimated for the inhaled treatments. GI, gastrointestinal; i.v., intravenous; PK, pharmacokinetic.

Lung absorption profile of glycopyrronium

Table 5 contains parameters taken or derived from the fitted parameters that relate back to the conceptual schema of the structural model and describe the PK of glycopyrronium after inhalation. As indicated in the table, glycopyrronium was predominantly absorbed unchanged into the systemic circulation through the lungs (93.1% of absorbed glycopyrronium), whereas a minor fraction (6.9%) was absorbed through the GI tract. With 56.5% of the inhaled dose being bioavailable, it follows that 52.6% of the inhaled dose was absorbed through the lungs, while only 3.9% was absorbed through the GI tract.

The model described drug absorption through the lungs as an overlap of three processes occurring at fast, intermediate and slow rates; the slow process accounted for 79% of the drug absorbed through the lungs. The half-life of the slow absorption phase was 80 h.

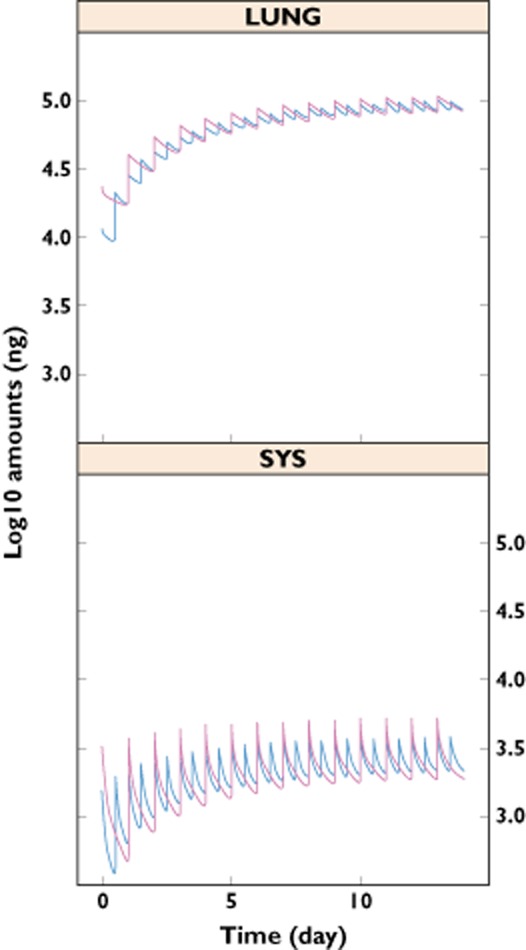

Multiple-dose simulation

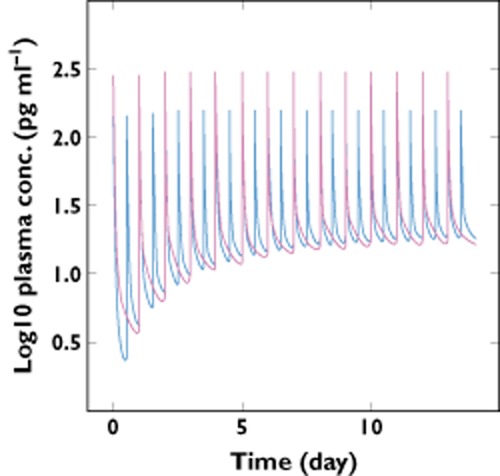

In order to obtain the PK profile of glycopyrronium over multiple doses, the simulation of once-daily and twice-daily regimens with a daily dose of 50 μg was performed to mimic a 14 day treatment. The plasma profile shown in Figure 4 indicates that glycopyrronium accumulated during the first few days and reached a steady state by day 7. About 100 μg of compound was present in the lung compartments at steady state (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 5, fluctuations within dosing intervals at steady state were smaller in the lung compartments than in the systemic compartments. Twice-daily dosing reduced peak-to-trough fluctuations at steady state in both systemic compartments and lungs compared with once-daily dosing (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Once-daily (50 μg) and twice-daily (2 × 25 μg) dosing plasma profile of glycopyrronium.  , inhaled twice daily;

, inhaled twice daily;  , inhaled once daily

, inhaled once daily

Figure 5.

Once-daily (50 μg) and twice-daily (2 × 25 μg) dosing pharmacokinetic profile of glycopyrronium in lung and systemic compartments. LUNG represents the sum of the amounts of drug in the intermediate and slow lung absorption compartments. SYS represents the sum of the amounts of drug in the three pharmacokinetic compartments, V1, V2 and V3.  , inhaled twice daily;

, inhaled twice daily;  , inhaled once daily

, inhaled once daily

Discussion

In this study, we have developed a model that is appropriate to describe the lung absorption of the LAMA glycopyrronium and to characterize its PK profile in the lung compartments and systemic circulation over multiple doses for once-daily and twice-daily regimens. The range of PK data used to build and validate our model was extensive. Pharmacokinetic profiles following single-dose inhalation were measured with and without concomitant oral administration of charcoal, with charcoal suppressing drug absorption through the GI tract. In addition, single-dose data following intravenous administrations and multiple-dose data following inhalation were available. The appropriateness of the model was demonstrated by standard model diagnostics and its ability to predict the PK profile of glycopyrronium when used to simulate both single and repeated once-daily inhalation. The validation of the model was performed using two independent studies, one of which was not used in model building. Thus, we also provided an external validation, confirming the usefulness of our model.

Our approach to quantify lung absorption processes is similar to that used for the characterization of the PK of formoterol [17] and insulin [18]. For formoterol, a fast absorption via the lungs with a half-life of 3.9 min has been identified, in addition to processes with half-lives of 27 min, 28.6 min and 6.5 h, which were attributed to absorption via the GI tract (starting with a lag time of 63 min), systemic distribution and systemic elimination, respectively [17]. The characterization of the formoterol PK was based exclusively on data after inhalation. Thus, there remains uncertainty with regard to the attribution of half-lives to elimination, distribution and different absorption processes of formoterol. In addition, it is also possible that a slower second absorption phase from the lungs was present and has been attributed to elimination (flip-flop kinetics), or was not identified because it occurred with a rate similar to elimination. For insulin, absorption after inhalation occurred with a half-life of about 30 min [18]. This assessment was based on data after inhalation and after i.v. administration. Therefore, in this insulin study, it was possible to differentiate between absorption and disposition processes. However, no data were available to differentiate absorption of insulin via the GI tract and via the lungs. For glycopyrronium, data after inhalation with and without oral charcoal were available in addition to the i.v. data. Based on these rich data, it became possible to reliably quantify and attribute disposition kinetics, absorption kinetics via the lungs and absorption kinetics via the GI tract.

Nevertheless, a mechanistic explanation of the different lung absorption processes cannot be proposed based on the available data. Additional experiments and studies together with physiologically based modelling approaches, such as that described by Gaz et al. [19], would be required in order to possibly attribute kinetic processes to physiological processes [20, 21].

Some apparent differences between our model predictions and the parameters from the noncompartmental analysis (Table 5) were observed and can be explained by experimental constraints and model characteristics. The noncompartmental estimation of the clearance was about 5% smaller than that derived from the model. This reflects the difference between the AUC value of the i.v. treatment calculated with the trapezoidal rule and the sampling schedule of the study and the AUC value obtained by integrating the polyexponential function describing the plasma profile.

The apparent terminal half-life was estimated to be between 50 and 60 h with the noncompartmental analysis, whereas the half-life of the rate-limiting process in our model, i.e. the slow lung absorption, was 80 h. The difficulties in obtaining reliable estimates of the terminal half-life of glycopyrronium for the inhaled treatments, which was due to its slower elimination after inhalation than after i.v. dosing, could account for this difference between the two analyses.

The AUC and Cmax values simulated for oral administration of glycopyrronium were somewhat higher than the measured values (Table 3). Likewise, the model inferred the absolute oral bioavailability to be 8.2%, whereas it was estimated to be 5% when determined by noncompartmental methods (Table 5). This difference may be explained by the fact that the data following direct oral administration were not used for model building. In addition, the estimate of 5% was obtained by comparing oral and i.v. data from different subjects (Part 1 and Part 2 of Study 1) [12]. Notably, the oral bioavailability estimated by our model is of the same order of magnitude as the one reported in the literature (7%) for oral administration of glycopyrronium [22]. Likewise, a low absolute bioavailability of glycopyrronium has been reported for children [23]. Therefore, our data for oral administration of glycopyrronium are consistent with previous data and confirm that glycopyrronium has a low oral bioavailability.

According to our model, 52.6% of the inhaled dose of glycopyrronium was absorbed through the lungs. Thus, our model suggests that about half of the glycopyrronium dose is deposited in the lungs. An additional 3.9% of the inhaled dose was absorbed in the GI tract. Together, the absolute bioavailability of inhaled glycopyrronium estimated by the model was 56.5%, whereas the one obtained in the noncompartmental analysis was 40%. Three factors could account for this difference. First, the difference in the estimated clearances of about 5% affects the estimates of the absolute bioavailability. Second, the fast lung absorption was modelled as an immediate bolus, whereas the noncompartmental analyses used the trapezoidal rule with a concentration of zero at time zero. This accounts for about 3% difference in AUC0–72 h, as illustrated by the difference in AUC values when setting concentration at time zero to zero (Table 3). Third, there is a marked difference in the extrapolation of the PK profiles beyond the last measured concentration related to the terminal half-lives. The ratio of the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0–Inf) to the area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration (AUC0–last) from the noncompartmental analysis was 1.36, whereas the ratio AUC0–Inf to AUC0–72 h obtained with the model from simulations with dense sampling up to 2000 h and excluding variability was 1.67.

The plasma concentration–time profiles obtained from the simulations, which are in agreement with those from PK studies used to build and validate the model, showed that the concentration of glycopyrronium decreased rapidly after i.v. administration, while a long tail in the plasma concentration was observed following inhaled administration. A similar plasma concentration–time profile, characterized by a rapid decline of concentrations in the first couple of hours after administration followed by a slow apparent terminal phase at very low concentrations, was obtained in a study analysing the PK of four different doses of glycopyrronium (25–200 μg) following repeated once-daily inhalation in patients with COPD [24]. These plasma concentration–time profiles suggest that a part of glycopyrronium is slowly absorbed from the lungs into the bloodstream, from where it is rapidly eliminated. Our model of lung absorption supports this hypothesis; the slow-phase absorption of glycopyrronium was indeed characterized by a half-life of about 3.5 days and was responsible for the majority (79%) of the drug absorbed through the lungs into the systemic circulation. The slow absorption of glycopyrronium results in an extended residence time in the lungs, which could explain the sustained bronchodilatation achieved in patients with COPD with once-daily dosing [6–10, 25].

Simulations of 50 μg once-daily and 25 μg twice-daily regimens generated similar PK profiles at steady state in both lungs and systemic compartments, even though a small reduction in peak-to-trough fluctuation was observed with twice-daily administration compared with once-daily administration. The clinical relevance of this reduction in terms of the optimal dosing regimen has yet to be determined. A recent study indicated that glycopyrronium 25 μg given twice daily produced greater bronchodilatation in terms of trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) than the same total dose administered once daily, although the difference was small and not statically significant [26]. However, once-daily and twice-daily regimens showed similar dose–response profiles for FEV1 area under the curve from 0 to 24 h, which takes into account the whole 24 h period postdose, with no significant difference between the two regimens. A recently published study aimed at evaluating the dose–response of once-daily and twice-daily doses of umeclidinium (GSK573719), a LAMA in development for the treatment of COPD, also failed to show a significant difference between once-daily and twice-daily dosing in terms of bronchodilatation over 24 h [27].

The model predicts that, despite its slow release from the lung compartments, glycopyrronium is rapidly cleared from the systemic circulation. Interestingly, the study by Sechaud et al. showed a moderate increase of total systemic exposure to glycopyrronium upon repeated once-daily dosing, as indicated by the estimated AUC accumulation ratios of 1.44 and 1.69 for the 100 and 200 μg doses [24]. The high systemic clearance estimated (44.9 l h−1) accounts for the rapid elimination from the circulation once the drug has been released from the lung. This may be advantageous for the drug's safety profile, because there is little risk of systemic drug accumulation during chronic dosing.

In conclusion, using a PK population model to characterize lung absorption, we have shown that the slow absorption of glycopyrronium from the lungs, together with its rapid elimination from the systemic circulation, could provide mechanistic insights into how once-daily dosing results in sustained 24 h bronchodilatation with low systemic adverse effects. The extended intrapulmonary residence time of glycopyrronium also provides pharmacokinetic evidence that it has the profile of a once-daily drug.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues who were involved in the planning, execution and analysis of the two clinical studies which provided the data used in this population pharmacokinetic modelling approach.

The authors were assisted in the preparation of the manuscript by Roberta Sottocornola, a professional medical writer contracted to CircleScience (Tytherington, UK) and Mark J. Fedele from Novartis. Writing support was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Competing Interests

All authors are employees of Novartis Pharma and declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2011. Updated December 2011. Available at http://www.goldcopd.org (last accessed 5 December 2012)

- 2.Lipworth BJ. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;42:697–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van den Bosch JM, Westermann CJJ, Aumann J, Edsbäcker S, Tönnesson, Selroos O. Relationship between lung tissue and blood plasma concentrations of inhaled budesonide. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1993;14:455–459. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510140511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton C, Patalano F, Fedele MJ, McBryan D. The right treatment for the right patient: the Novartis view on COPD. Nature. 2012;489(Suppl. 7417):S1–48. Available at http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v489/n7417_supp/index.html#top (last accessed 4 April 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansel TT, Neighbour H, Erin EM, Tan AJ, Tennant RC, Maus JG, Barnes PJ. Glycopyrrolate causes prolonged bronchoprotection and bronchodilatation in patients with asthma. Chest. 2005;128:1974–1979. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Urzo A, Ferguson GT, van Noord JA, Hirata K, Martin C, Horton R, Lu Y, Banerji D, Overend T. Efficacy and safety of once-daily NVA237 in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: the GLOW1 trial. Respir Res. 2011;12:156. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-156. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fogarty C, Hattersley H, Di Scala L, Drollmann A. Bronchodilatory effects of NVA237, a once daily long-acting muscarinic antagonist, in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2011;105:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerwin E, Hébert J, Gallagher N, Martin C, Overend T, Alagappan VK, Lu Y, Banerji D. Efficacy and safety of NVA237 versus placebo and tiotropium in patients with COPD: the GLOW2 study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1106–1114. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00040712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verkindre C, Fukuchi Y, Flemale A, Takeda A, Overend T, Prasad N, Dolker M. Sustained 24-h efficacy of NVA237, a once-daily long-acting muscarinic antagonist, in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2010;104:1482–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogelmeier C, Verkindre C, Cheung D, Galdiz JB, Güçlü SZ, Spangenthal S, Overend T, Henley M, Mizutani G, Zeldin RK. Safety and tolerability of NVA237, a once-daily long-acting muscarinic antagonist, in COPD patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tronde A, Bosquillon C, Forbes B. The isolated perfused lung for drug absorption studies. In: Ehrhardt C, Kim KJ, editors. Drug Absorption Studies. Springer US: 2008. pp. 135–163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sechaud R, Sudershan M, Perry S, Hara H, Drollmann A, Karan R, Di Scala L, Biswal S, Patterson B, Kaiser G. Efficient deposition and sustained lung concentrations of NVA237 after inhalation via the Breezhaler®device in man. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(Suppl. 56):889s. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beal SL, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann A, Bauer RJ. NONMEM Project Group. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 1992. NONMEM users guides, parts I-VII. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN. PsN-Toolkit – a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;79:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelfand AE, Hills SE, Racine-Poon A, Smith AFM. Illustration of bayesian inference in normal data models using Gibbs sampling. J Am Stat Assoc. 1990;85:972–985. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derks MGM, van den Berg BTJ, van der Zee JS, Braat MCP, van Boxtel CJ. Biphasic effect-time courses in man after formoterol inhalation: eosinopenic and hypokalemic effects and inhibition of allergic skin reactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:824–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potocka E, Baughman RA, Derendorf H. Population pharmacokinetic model of human insulin following different routes of administration. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51:1015–1024. doi: 10.1177/0091270010378520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaz C, Cremona G, Panunzi S, Patterson B, De Gaetano A. A geometrical approach to the PKPD modelling of inhaled bronchodilators. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2012;39:415–428. doi: 10.1007/s10928-012-9259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsson B, Bondesson E, Bongstrom L, Edsbäcker S, Eirefelt S, Ekelund K, Gustavsson L, Hegelund-Myrbäck T. Pulmonary drug metabolism, clearance, and absorption. In: Smyth HDC, Hickey AJ, editors. Controlled Pulmonary Drug Delivery. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upton RN, Doolette DJ. Kinetic aspects of drug disposition in the lungs. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:381–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali-Melkkilä T, Kaila T, Kanto J. Glycopyrrolate: pharmacokinetics and some pharmacodynamic findings. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1989;33:513–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1989.tb02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rautakorpi P, Manner T, Ali-Melkkilä T, Kaila T, Olkkola K, Kanto J. Pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of glycopyrrolate in children. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;83:132–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sechaud R, Renard D, Zhang-Auberson L, Motte SL, Drollmann A, Kaiser G. Pharmacokinetics of multiple inhaled NVA237 doses in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50:118–128. doi: 10.5414/cp201612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beeh K, Singh D, Di Scala L, Drollmann A. Once-daily NVA237 improves exercise tolerance from the first dose in patients with COPD: the GLOW3 trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:503–513. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S32451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arievich H, Overend T, Renard D, Gibbs M, Alagappan V, Looby M, Banerji D. A novel model-based approach for dose determination of glycopyrronium bromide in COPD. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donohue JF, Anzueto A, Brooks J, Mehta R, Kalberg C, Crater G. A randomized, double-blind dose-ranging study of the novel LAMA GSK573719 in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2012;106:970–979. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]