Abstract

Aims

The aim of the study was to explore and compare junior doctors' perceptions of their self-efficacy in prescribing, their prescribing errors and the possible causes of those errors.

Methods

A cross-sectional questionnaire study was distributed to foundation doctors throughout Scotland, based on Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory and Human Error Theory (HET).

Results

Five hundred and forty-eight questionnaires were completed (35.0% of the national cohort). F1s estimated a higher daytime error rate [median 6.7 (IQR 2–12.4)] than F2s [4.0 IQR (0–10) (P = 0.002)], calculated based on the total number of medicines prescribed. The majority of self-reported errors (250, 49.2%) resulted from unintentional actions. Interruptions and pressure from other staff were commonly cited causes of errors. F1s were more likely to report insufficient prescribing skills as a potential cause of error than F2s (P = 0.002). The prescribers did not believe that the outcomes of their errors were serious. F2s reported higher self-efficacy scores than F1s in most aspects of prescribing (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Foundation doctors were aware of their prescribing errors, yet were confident in their prescribing skills and apparently complacent about the potential consequences of prescribing errors. Error causation is multi-factorial often due to environmental factors, but with lack of knowledge also contributing. Therefore interventions are needed at all levels, including environmental changes, improving knowledge, providing feedback and changing attitudes towards the role of prescribing as a major influence on patient outcome.

Keywords: junior doctors, human error theory, patient safety, prescribing errors, self-efficacy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Junior doctors are responsible for the vast majority of prescription writing in the acute hospital setting.

The error rate per prescribed item is higher for foundation doctors than for their more senior colleagues.

Errors result from a complex combination of system and individual factors.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The majority of doctors acknowledged that they make prescribing errors, but expressed high levels of confidence about their ability to prescribe.

It was perceived that whilst error causation was largely environmental, there remained a substantial proportion perceived to be due to lack of knowledge

Doctors in their second year of postgraduate medical training (F2s) were more confident than doctors in their first year (F1s) and estimated a lower error rate. Most doctors in training did not believe their errors will have serious consequences for them or their patients.

Introduction

Foundation doctors [i.e. doctors in their first 2 years of postgraduate medical training (F1 and F2)] are responsible for the majority of prescription writing in hospitals [1]. Dornan et al. recently reported that the overall error rate in prescriptions was 8.9%, with corresponding error rates of 8.4% in prescriptions written by F1s and 10.3% by F2s, in comparison with 5.9% by consultants [2]. A prevalence study conducted in Scotland by the authors of this study, reported similar error rates of 7.5% overall, with 7.4% for F1 doctors, 8.6% for F2s, and 6.3% for consultants [3].

Recent international and national (UK) initiatives (for example from the World Health Organization [4] and the British Pharmacological Society [5]) have described key competencies which medical students must achieve in order to prescribe safely and effectively on graduation and throughout their medical careers. Indeed, the working party of the General Medical Council (GMC) [6] made recommendations that were adopted in the latest version of Tomorrow's Doctor, aimed at ensuring safe practice [7]. Much attention has focused on improving the teaching of clinical pharmacology and prescribing skills, e.g. by adopting problem based learning approaches and the development of appropriate assessment techniques [8–10].

Few studies have investigated foundation doctors' perceptions of their own prescribing errors, their knowledge of, or attitudes towards, prescribing errors, and potential consequences of prescribing errors. The aim of this study was to explore and compare the perceptions of doctors in their first and second years of training about the causes and consequences of prescribing errors, error rates, and their confidence about prescribing. The theoretical basis of our work was primarily Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [11] and Reason's Human Error Theory (HET) [12].

SCT deals with cognitive, emotional aspects and aspects of behaviour for understanding behaviour change. There are various elements to SCT, including self-efficacy (defined as people's beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over events that affect their lives) and outcome expectancies (the perceptions of the probability of an outcome occurring) [13].

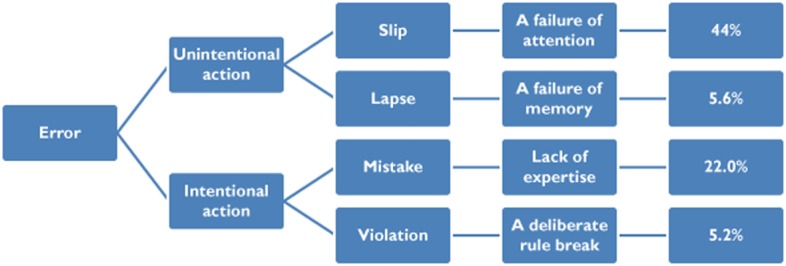

Reason's Human Error Theory allows for the classification of the type of error that occurs, based on an assessment of the actions that led to that error. An unintentional action may lead to an error due to a failure of attention (slip) or memory (lapse), and an intentional action may lead to an error due to a failure or lack of expertise (mistake) or a deliberate rule break (violation) (Figure 1). HET also recognizes errors as a consequence of latent (e.g. organizational and management factors) and error producing (e.g. environmental, team, individual factors) conditions [12].

Figure 1.

Classificaton of error type according to Reasons' Human Error Theory [12]

The current study was part of a wider programme of work, which also included an observational prevalence study conducted in nine sites in Scotland [3].

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional questionnaire study structured around SCT [11] and HET [12].

Subjects and setting

All F1 (n = 781) and F2 (n = 783) doctors working in Scottish hospitals between October 2010 and January 2011 were included.

Questionnaire development

The content of the questionnaire was informed by semi-structured interviews, conducted with a purposive sample of 22 F1 and F2 doctors throughout Scotland [14].

After a paper pre-pilot exercise with 16 middle grade doctors, a formal ‘on-line’ pilot was undertaken [via a weblink sent by NHS Education Scotland (NES)] to a further 200 randomly selected speciality trainee doctors. The low response rate achieved (4.5%) was attributed to both the online distribution method and the questionnaire length. The questionnaire was shortened, by reducing the number of open text questions, but retained the theory-based items.

The final questionnaire comprised the following sections:

demographics,

awareness of own prescribing errors, estimated error rates and decisions made,

description of a prescribing error the respondent had made (open text question), and perceived causal factors (selected from a list of the factors (n = 23) based on HET and previous studies (Dean) [1],

Self-efficacy (confidence) in prescribing (based on SCT [11], using 10-point scaled responses to assess the level of confidence about a variety of actions (deciding on the most appropriate treatment (five items), writing a prescription (three items) and asking for help (one item),

Outcome expectancies of prescribing errors using seven-point scaled responses to assess the likelihood of potential consequences of prescribing errors [prescriber outcomes, e.g. reputational impact (four items)] and potential patient outcomes (two items).

Questionnaire administration

The questionnaire was distributed in three ways, over a 3 month period from October 2010 to January 2011: (i) by a member of the study team at the start of F1 and to F2s at a seminar in the hospitals participating in the linked observational prevalence study [3]. The seminar was either on patient safety or prescribing and was organized by the researchers or was a routine foundation doctors' training seminar. Completion of the questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous, and taken as assumed consent, (ii) distributed by foundation programme directors in a convenience sample of additional hospital throughout Scotland and (iii) online distribution via a weblink sent by NES to all foundation doctors in Scotland. Each version of the questionnaire had an initial screening question to minimize duplicate completion.

Data management

Data were entered into an IBM SPSS version 19 database. Accuracy of data entry was assessed on a 10% sample by double data entry, for which there was 100% agreement.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics, means (SD) and medians (IQR) were calculated. Chi-squared (χ2) tests were used to assess the association between the perceived causes of prescribing errors and year of training (F1 or F2), and to compare the proportion of independent prescribing decisions made between F1 and F2 doctors. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to compare estimated day time and night time error rates. The Mann Whitney U-test was used to compare estimated median day time and night time error rates, confidence in prescribing and the consequences of prescribing between F1 and F2 doctors. An overall self-efficacy score was computed by summing the responses to the nine individual items. Sub-scales for self-efficacy in prescription writing and in decision making were also calculated. Cronbach alpha (Cα) was used to test the interval reliability of the scale. Results were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05. The errors reported as open text responses were analyzed in accordance with HET (Figure 1).

Ethical approval for the overall study was gained from North of Scotland Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Response rates and demography

The 548 returned questionnaires equated to 35.0% (548/1564) of the national cohort and a response rate of 89.9% for seminar attendees. The majority of the respondents were F1s [64.4% (353)], female [58.9% (323)] and Scottish medical school graduates [79.9% (438)], and the most common areas of experience were general surgery (66.6%) and general medicine (63.7%) (note respondents could select several answers).

Awareness of prescribing errors and prescribing decisions made

A total of 514 (93.8%) respondents estimated their day time prescribing error rate i.e. the number of prescriptions containing errors per 100 prescriptions written. This was significantly higher for F1 doctors (median 6.7. IQR 2–12.4) than F2s (median 4, IQR 0–10, P = 0.002). Fewer respondents [78.8% (432)] estimated their night shift error rate which was higher than the day time rate [F1 10 (IQR 4–20), F2 10 (IQR 4–20)]. The difference between F1s and F2s was not statistically significant (P = 0.742).

When asked about the proportion of independent prescribing decisions made, 63.4% of F2s reported being responsible for ≥50% of decisions made in comparison with 36.4% for F1s (P < 0.001).

Error type reported

Nearly all respondents (504; 92.0%) gave an example of an error they had made. Based on a list of options provided to determine the outcome of the error reported, respondents stated that the majority of errors did not reach the patient [328 (64.6%)] and were not reported to senior colleagues or through the hospital reporting system [371 (73.0%)]. Two hundred and fifty errors (49.2%) resulted from an unintentional action i.e. a slip (222, 43.7%) or a lapse (28; 5.5%); 111 (21.9%) errors were due to either a failure or lack of expertise (mistakes), whilst 26 (5.1%) were deliberate rule breaks/violations. One hundred and eleven (21.9%) errors were not classifiable using HET (e.g. insufficient information provided, reason given not part of the theory). Six (1.2%) of the examples provided were administration errors rather than prescribing errors and were therefore not included. Examples of each type of error are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of errors reported by respondents

| Error type | Description of error provided | Description of cause provided |

|---|---|---|

| Slip | Writing once daily instead of once weekly for risedronate | I was writing a lot of medications that were to be given once daily and that was amongst them. |

| Lapse | I forgot to tick an administration time for digoxin when re-writing a drug chart. The patient didn't receive it over the weekend until a nurse alerted the on-call team that he was tachycardic. | Not checking over what I'd written. |

| Mistake | Prescribed clarithromycin concurrently with simvastatin. | Lack of knowledge re drug interactions. Lack of knowledge re maximum dose. |

| Violation | Prescribing penicillin to an allergic patient. | Asked to prescribe it on ward round – did not check allergies section. |

Perceived causes of prescribing errors

Respondents most commonly identified their workload, being interrupted whilst prescribing, and pressure from other staff, as factors contributing to error causation (Table 2). There was little difference in the perceived causes of prescribing errors between F1s and F2s, although a greater proportion of F1s cited having insufficient skills in prescribing as a potential cause more often than F2s (P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Perceived causes of reported prescribing error as per list provided (n (%))

| Total Yes | F1 | F2 | * P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Maybe | No | Yes | Maybe | No | |||

| Work environment | ||||||||

| Heavy workload | 313 | 203 (61.5) | 69 (20.9) | 58 (17.6) | 110 (59.1) | 39 (21.0) | 37 (19.9) | 0.795 |

| Interruption | 304 | 192 (57.7) | 76 (22.8) | 65 (19.5) | 112 (60.2) | 33 (17.7) | 41 (22.0) | 0.373 |

| New or locum staff | 77 | 47 (14.5) | 38 (11.7) | 239 (73.8) | 30 (16.4) | 25 (13.7) | 128 (69.9) | 0.650 |

| Low staffing levels | 185 | 117 (35.8) | 65 (19.9) | 145 (44.3) | 68 (36.8) | 35 (36.8) | 82 (44.3) | 0.958 |

| Cross cover of patients | 194 | 130 (39.4) | 50 (15.2) | 150 (45.5) | 64 (34.4) | 36 (19.4) | 86 (46.2) | 0.356 |

| Lack of support from other staff | 111 | 80 (24.5) | 71 (21.8) | 175 (53.7) | 31 (16.9) | 39 (21.3) | 113 (61.7) | 0.107 |

| Pressure from other staff | 228 | 153 (46.4) | 71 (21.5) | 106 (32.1) | 75 (40.8) | 43 (23.4) | 66 (35.9) | 0.469 |

| Difficult physical environment | 127 | 85 (26.2) | 67 (20.6) | 173 (53.2) | 42 (23.1) | 40 (22.0) | 100 (54.9) | 0.738 |

| Shift pattern | 174 | 112 (33.7) | 53 (16.0) | 167 (50.3) | 62 (33.5) | 43 (23.2) | 80 (43.2) | 0.099 |

| Team factors | ||||||||

| Inadequate written communication within team | 130 | 86 (26.4) | 49 (15.0) | 191 (58.6) | 44 (24.0) | 29 (15.9) | 110 (60.1) | 0.841 |

| Inadequate verbal communication within team | 121 | 78 (23.9) | 57 (17.4) | 192 (58.7) | 43 (23.6) | 26 (14.3) | 113 (62.1) | 0.627 |

| Adequate supervision not available | 62 | 47 (14.4) | 69 (21.2) | 210 (64.4) | 15 (8.2) | 38 (20.8) | 130 (71.0) | 0.105 |

| Team made up of the wrong type of staff | 51 | 34 (10.5) | 42 (12.9) | 249 (76.6) | 17 (9.3) | 26 (14.2) | 140 (76.5) | 0.859 |

| Unclear roles and responsibilities | 36 | 28 (8.6) | 41 (12.6) | 257 (78.8) | 8 (4.4) | 20 (11.0) | 154 (84.6) | 0.237 |

| Task factors | ||||||||

| Guidelines/policies unavailable | 61 | 45 (13.8) | 38 (11.7) | 243 (74.5) | 16 (8.7) | 26 (14.2) | 141 (77.0) | 0.201 |

| Test results unavailable/inaccurate | 33 | 19 (5.9) | 36 (11.1) | 269 (83.0) | 14 (7.7) | 23 (12.6) | 146 (79.8) | 0.626 |

| Lack of familiarity with medication | 151 | 97 (29.7) | 69 (21.1) | 161 (49.2) | 54 (29.5) | 35 (19.1) | 94 (51.4) | 0.847 |

| Patient factors | ||||||||

| Poor communication with patient | 51 | 27 (8.3) | 48 (14.7) | 252 (77.1) | 24 (13.2) | 29 (15.9) | 129 (70.9) | 0.169 |

| Complex patient | 113 | 73 (22.3) | 58 (17.7) | 196 (59.9) | 40 (22.2) | 34 (18.8) | 106 (58.8) | 0.948 |

| Individual factors | ||||||||

| Tiredness/stress | 230 | 155 (46.7) | 97 (29.2) | 80 (24.1) | 75 (40.8) | 66 (35.9) | 43 (23.4) | 0.270 |

| Having insufficient theoretical knowledge | 126 | 87 (26.9) | 66 (20.4) | 170 (52.6) | 39 (21.4) | 40 (22.0) | 103 (56.6) | 0.390 |

| Having insufficient skills in prescribing | 60 | 46 (14.2) | 78 (24.1) | 200 (61.7) | 14 (7.7) | 27 (14.9) | 140 (77.3) | 0.002 |

| Poor motivation | 28 | 19 (5.8) | 47 (14.5) | 259 (79.7) | 9 (4.9) | 32 (17.4) | 143 (77.7) | 0.637 |

Chi square test comparing F1s with F2s.

Self-efficacy in prescribing

Reported self-efficacy was generally high for all listed aspects of prescribing [aggregate score 8.4 out of 10 (IQR 7.8–9)], with F2s [aggregate score 8.7 (IQR 8.2–9.2)] reporting a higher score than F1s [aggregate score 8.2 (IQR 7.4–8.8)] (P < 0.001) (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the overall self-efficacy score calculated for prescription writing between F1s and F2s (P = 0.156) or in their ability to ask for help with prescribing (P = 0.892), with all respondents reporting high levels of self-efficacy in each of these [aggregate scores 9.3 (IQR 8.3–10) and 10 (IQR 8.7–10), respectively].

Table 3.

Self-efficacy in prescribing

| Statement | n* (F1, F2) | Overall Median (IQR)* | F1 Median (IQR) | F2 Median (IQR) | Mann Whitney U Test (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy in prescription writing | |||||

| I can write the prescription without missing anything out | 533 (342, 187) | 9 (8–10) | 8 (7–10) | 9 (8–10) | 0.117 |

| I can fill out the kardex | 531 (342, 185) | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 0.375 |

| I can write the prescription legibly | 534 (343, 187) | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 0.355 |

| Aggregate score for self-efficacy in prescription writing | 529 (340, 185) | 9.3 (8.3, 10) | 9.3 (8.3, 10) | 9.3 (8.7, 10) | 0.156 |

| Self-efficacy in decision making | |||||

| I can decide on the most appropriate duration of treatment | 530 (340, 186) | 7 (6–8) | 7 (5–8) | 8 (7–9) | <0.001 |

| I can decide on the most appropriate dose | 529 (340, 185) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–8.75) | 9 (8–9) | <0.001 |

| I can decide on the most appropriate timing | 532 (342, 186) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–9) | 9 (8–9) | <0.001 |

| I can decide on the most appropriate route of delivery | 532 (324, 186) | 8 (8–9) | 8 (7–9) | 9 (8–10) | <0.001 |

| I can decide on the most appropriate formulation | 532 (341, 187) | 8 (6–9) | 7 (6–8) | 8 (7–9) | <0.001 |

| Aggregate score for self-efficacy in decision making | 522 (333, 185) | 7.8 (7.0, 8.6) | 7.4(6.6, 8.2) | 8.4 (7.6, 9.0) | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy in requesting help | |||||

| I can ask for help with prescribing if needed | 528 (340, 184) | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 0.892 |

| Overall aggregate self-efficacy | 516 (330, 182) | 8.4 (7.8, 9) | 8.2 (7.4, 8.8) | 8.7 (8.2, 9.2) | <0.001 |

Includes the four respondents for whom F1/2 status is unknown. Measured on a scale of 1–10, where 1: cannot do at all, 10: highly certain can do. **Mann Whitney U-test.

F2s reported higher self-efficacy scores for all aspects of decision-making (deciding on the most appropriate dose, duration, timing, route of administration and formulation) than F1s [aggregate scores 8.4 (IQR 7.6, 9.0) and 7.4 (IQR 6.6, 8.2), respectively] (P < 0.001), but there was no difference between cohorts and asking for help (P = 0.892).

Perceived consequences of prescribing errors

Referral to the GMC [median 2 (IQR 2–4)] and completing an error reporting form [median 3 (IQR 2–4)] were the least likely perceived consequences of prescribing errors. F1s were more likely to believe that prescribing errors would be picked up before reaching the patient than F2s (P = 0.032) and that being reprimanded by senior colleagues was a more likely consequence of a prescribing error (P = 0.028) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Perceived consequences of prescribing errors

| Statement | n* (F1, F2) | Overall Median (IQR)* | F1 Median (IQR) | F2 Median (IQR) | P** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will be referred to the General Medical Council | 523 (336,183) | 2 (2–4) | 2.5 (2–4) | 2 (2–4) | 0.600 |

| I will have to fill out an error reporting form | 532 (340,188) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4.75) | 4 (2–5) | 0.070 |

| It will impact upon my professional reputation | 524 (334,186) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.517 |

| It will have an adverse effect on the patient | 525 (337,186) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.628 |

| I will be reprimanded by senior colleagues | 523 (333,186) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.028 |

| It will be picked up before reaching the patient (e.g. by pharmacist, nurse, colleagues, patient) | 534 (342,188) | 5 (5–6) | 5 (5–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.032 |

Includes the four respondents for whom F1/2 status is unknown

Mann Whitney U-test. Measured on a scale of 1–7, where 1 was ‘very unlikely’ and 7 was ‘very likely’.

Discussion

The major findings of this study were that: (i) junior doctors estimated an error rate of 5% of items prescribed, with doctors in the first year of training estimating a slightly higher rate, (ii) overall confidence (self-efficacy) in various competencies associated with prescribing was high in spite of the awareness that errors were made regularly and (iii) based on HET classifications, errors were largely due to slips or lapses, with environmental conditions (Table 2) playing a significant part in their causation.

The self-reported error rates in the present study are similar but lower than those reported in published observational studies and in our linked prevalence study [2, 3]. Interestingly, F2 doctors estimated a lower personal error rate than F1s. When these figures are compared with published studies and our linked prevalence study [2, 3], they suggest that F2s had an unrealistic perception of their performance. However, this should be interpreted with caution as the true error rate for doctors who participated in this study is unknown. There were differences in scores for self-efficacy between cohorts, with F2 doctors scoring higher than F1 doctors. This concurs with findings by Rothwell et al. that confidence in prescribing increases with practical experience and support [15] and with studies where F1s report finding these decisions challenging. However, the overall high level of self-efficacy in prescribing by both foundation cohorts may indicate misplaced confidence, given the high levels of errors identified by self-report and by our parallel prevalence study [3]. Other studies have shown a mismatch between clinical confidence and observed competence [16, 17], which could offer an explanation for the observations in the present study. However, defining and achieving the appropriate level of confidence to ensure error free prescribing is challenging. Whilst over-confidence is not desirable, a lack of confidence may also lead to error. Errors (particularly serious errors and those that pose the risk of litigation), impact negatively on prescribers, leading to emotional distress, as well as need for support and changes in their relationships with colleagues and patients [18, 19]. This in turn, can diminish their perceived confidence in their ability, and as demonstrated by West and colleagues, lead to more errors [20].With regard to doctors' self-efficacy in the various aspects of prescribing, the physical act of writing a prescription was not considered problematic by either foundation year cohort, with respondents reporting high levels of confidence in their ability to complete a prescription chart and write legibly. However, a recent study by Franklin et al. reported that of 6237 medication orders written, almost 3% were incomplete and nearly 1% illegible [21], while results from our large prevalence study, demonstrated that of 3364 errors identified, 2% were due to illegibility whilst 15% were incomplete prescriptions [3].

In the current study, doctors were confident that prescribing errors would be intercepted before reaching the patient, although F2s were less certain. In addition, the data suggest that doctors may feel it is acceptable to make a certain proportion of errors, presumably based on the assumption that all prescription orders will be reviewed by a pharmacist. However, not all members of the multi-disciplinary team provide an out-of-hours or weekend service, and more importantly, pharmacists may not be able to provide a clinical service to all hospital wards in times of financial constraint.

The reporting of medication errors commonly informs risk management strategies. Yet doctors are less likely to report medication errors than either pharmacists or nurses [22] and we found that doctors thought having to complete an error reporting form, would be an unlikely consequence of a prescribing error.

Around half the self-reported errors were reported to be unintentional (slips or lapses). Such errors are unlikely to be reduced by increasing knowledge or motivation, contrary to recent calls for increased education. For this specific error type i.e. slip/lapse, improvements are more likely with interventions that tackle other latent factors and error producing conditions. In the majority of these cases, this was because the error resulted from the actions of others, was due to circumstances out with their control or a lack of data provided by the respondent. This raises important issues in terms of accountability given that the prescribing foundation doctor may have correctly transcribed the information they were provided with either verbally or in writing. Recently, Ross et al. reported that in 61% of cases where a new medicine was prescribed, the doctor responsible for the decision to prescribe was not the doctor who wrote the prescription [23].

Foundation doctors reported the perceived causes of prescribing errors to be multi-factorial, concurring with the findings of Dean et al. [1] and Coombes et al. [24] that systems and environmental factors are most important. However, more than a quarter reported that having insufficient theoretical knowledge was associated with errors. Furthermore, almost 30% of respondents reported that lack of familiarity with particular medications caused errors. Together, these views are consistent with concerns expressed by the wider profession and highlight the opportunity to reduce a proportion of errors with improved education [25, 26]. Doctors were confident that they could ask for help with prescribing if required, but this assumes that foundation doctors recognize when they should ask for help and that they receive the correct advice.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study were the theory-based construction of the questionnaire and the high proportion of responses from those attending training sessions. The limitations include the subjective nature of the responses, recall bias and biases within the sample and the fact that the true error rate for the participants was not known. The responses received were specific to the time point at which the data were collected. Had the study been conducted either earlier or later in the training year, estimated rates may have differed.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that junior doctors were aware of their prescribing errors, yet were confident in their prescribing skills and apparently complacent about the potential consequences of prescribing errors. Error causation is multi-factorial and suggests that multi-faceted interventions are needed at all levels. The types of interventions at the prescriber level should include those which focus on improving knowledge, encouraging reflective practice, and reporting errors when they occur. Additionally, changing attitudes on towards the role of prescribing as a major influence on patient outcome is required. Despite many initiatives in this area, a major safety issue still remains. These should be addressed systematically, using a theoretical framework to achieve long term solutions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank those who facilitated data collection and the doctors who participated in the study. This study was funded by the Chief Scientist Office for the Scottish Government Health Directorates.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author). We have not received support from any organization for the submitted work, we have not had financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and we do not have any relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dornan T, Ashcroft D, Heathfield H, Lewis P, Miles J, Taylor D, Tully M, Wass V. An in-depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education: EQUIP study. Final report to the General Medical Council. University of Manchester: School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and School of Medicine.: eScholarID:83866 Available at http://www.medschools.ac.uk/Publications/Pages/Safe-Prescribing-Working-Group-Outcomes.aspx (last accessed 12 June 2012)

- 3.Ryan C, Bond C, Ross S, Davey P, Francis J, Johnston M, Ker J, Lee A, MacLeod MJ, Maxwell S, McKay G, McLay J, Webb D, the PROTECT team The prevalence of prescribing errors amongst junior doctors in Scotland. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(Suppl. 1):34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vries TP, Henning RH, Hogerzeil HV, Fresle DA. Guide to Good Prescribing. Geneva: WHO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.British Pharmacological Society. Ten principles of good prescribing. 2010. Available at http://www.bps.ac.uk/SpringboardWebApp/userfiles/bps/file/Clinical/BPSPrescribingStatement03Feb2010.pdf (last accessed 6 February 2012)

- 6.Lechler R, Paice E, Hays R, Petty-Saphon K, Aronson J, Bramble M, Hughes I, Rigby E, Anwar Q, Webb D, Maxwell S, Martin J, Maskrey N, Walker S. Outcomes or the medical schools council safe prescribing working group. November 2007. Available at http://www.medschools.ac.uk/publications/pages/safe-prescribing-working-group-outcomes.aspx (last accessed 6 February 2012)

- 7.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's doctor. London GMC; 2009. Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/TomorrowsDoctors_2009.pdf_39260971.pdf (last accessed 6 February 2012)

- 8.O'Shaughnessy L, Inam H, Maxwell S, Llewelyn M. Teaching of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics in UK medical schools: current status in 2009. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross S, Maxwell S. Prescribing and the core curriculum for tomorrow's doctors: BPS Curriculum in clinical pharmacology and prescribing for medical students. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:644–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mucklow J, Bollington L, Maxwell S. Assessing prescribing competence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:632–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reason J. Human Error. Cambridge: University of Cambridge; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 71–81. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan EM, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Davey P, Maxwell S, McKay G, McLay J, Ross S, Ryan C, Webb DJ, Bond C behalf of the PROTECT study group. Learning curves, taking instructions and patient safety: using a theoretical domains framework in an interview study to investigate prescribing errors among doctors in training. Implement Sci. 2012;7:86. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-86. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothwell C, Burford B, Morrison J, Morrow G, Allen M, Davies C, Baldauf B, Spencer J, Johnson N, Peile E, Illing J. Junoir doctors prescribing: enhancing their learning in practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynne G, Marteau TM, Johnston M, Whiteley CA, Evans T. The inability of trained nurses to perform basic life support. Br Med J. 1987;294:1198–1199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6581.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnsley L, Lyon PM, Ralston SJ, Hibbert EJ, Cunningham I, Gordon FC, Field MJ. Clinical skills in junior medical officers: a comparison of self-reported confidence and observed competence. Med Educ. 2005;38:358–367. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Armitage G. Coping with medical error: a systematic review of papers to assess the effects of involvement in medical errors on healthcare professionals' psychological well-being. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e43. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.035253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seys D, Van Gerven E, Euwema M, Panella M, Scott SD, Conway J, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36:135–162. doi: 10.1177/0163278712458918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, Shanafelt TD. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy. A prospective longitudinal study. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dean-Franklin B, Reynolds M, AtefSheb N, Burnett S, Jacklin A. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a three-centre study of their prevalence, types and causes. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:739–745. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2011.117879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarvadikar A, Prescott G, Williams D. Attitudes to reporting mediation error among differing healthcare professionals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:843–853. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0838-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross S, Hamilton L, Ryan C, Bond CM. Who makes prescribing decisions in hospital in-patients? An observational study. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88:507–510. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coombes ID, Stowasser DA, Coombes JA, Mitchell C. Why do interns make prescribing errors? A qualitative study. Med J Aust. 2008;188:89–94. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobriq M, McLay J, Ross S. Foundation year 1 doctors and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics teaching. A retrospective view in light of experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:363–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02925.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erice Medication Errors Research Group. Medication errors: problems and recommendations from a consensus meeting. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:592–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]