SUMMARY

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is an obligate human pathogen that can escape immune surveillance through antigenic variation of surface structures such as pili. A G-quadruplex-forming (G4) sequence (5´-G3TG3TTG3TG3) located upstream of the N. gonorrhoeae pilin expression locus (pilE) is necessary for initiation of pilin antigenic variation, a recombination-based, high-frequency, diversity-generation system. We have determined NMR-based structures of the all-parallel-stranded monomeric and novel 5´-end-stacked dimeric pilE G-quadruplexes in monovalent cation-containing solutions. We demonstrate that the three-layered all-parallel-stranded monomeric pilE G-quadruplex containing single residue double-chain-reversal loops, that can be modeled without steric clashes into the three-nucleotide DNA-binding site of RecA, binds and promotes E. coli RecA mediated strand exchange in vitro. We discuss how interactions between RecA and monomeric pilE G-quadruplex could facilitate the specialized recombination reactions leading to pilin diversification.

INTRODUCTION

DNA recombination is common to all organisms and is utilized to repair DNA and generate genetic diversity. In normal cells, most DNA recombination reactions occur at low frequency but in many genetic diversity-generating systems, such as immunoglobin class-switching, yeast mating-type switching or pathogenesis associated antigenic variation, programmed recombination reactions occur at a relatively high frequency (Criss et al., 2005; Haber, 1998; Maizels, 2006). DNA recombination is generally beneficial to the organism but can also be detrimental; such is the case for chromosomal translocations, which are the molecular signature for many types of cancer (Zhang et al., 2010).

The obligate human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a gram-negative bacterium, which relies on type IV pili for twitching motility, adherence to host cells, and natural DNA transformation (Rudel et al., 1992; Sparling, 1966; Wolfgang et al., 1998). Pili are mainly composed of pilin, which antigenically varies at a high frequency by a gene conversion process (Criss et al., 2005). Pilin antigenic variation results from non-reciprocal DNA recombination between one of many silent pilin loci termed pilS and the pilin expression locus, pilE (Hagblom et al., 1985). Genetic, pharmacological and biophysical experiments show that pilin antigenic variation requires a cis-acting DNA element situated upstream of pilE with the sequence 5´-G3TG3TTG3TG3 that forms a G-quadruplex structure in the bacterial cell and in vitro (Cahoon and Seifert, 2009).

G-quadruplexes are four-stranded structures formed by G-rich sequences through formation of stacked G•G•G•G tetrads (G-tetrads) in monovalent cation-containing solutions (Burge et al., 2006; Neidle, 2009; Patel et al., 2007). The length and number of individual G-tracts and the length and sequence context of linker residues define the diverse topologies adopted by G-quadruplexes. Bearing homology rather than complementarity of four interacting bases, and thus devoid of coding functions, G-quadruplexes have long been considered as genomic outliers (Davis, 2004). However, recently G-quadruplexes have drawn significant interest because of an ever-expanding repertoire of experiments indicative of their potential biological roles impacting oncogenic promoter regions (Balasubramanian et al., 2011; Qin and Hurley, 2008), telomeric DNA (Paeschke et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2011), regions of genomic instability (Ribeyre et al., 2009), and the discovery of enzymes acting on G-quadruplex topology (Huber et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2008) [reviewed in (Lipps and Rhodes, 2009; Maizels, 2006; Sissi et al., 2011)]. It was also earlier hypothesized that intermolecular parallel-stranded G-quadruplexes may be involved in the alignment and recombination of sister chromatids during meiosis (Liu and Gilbert, 1994; Sen and Gilbert, 1988).

We have recently initiated a systematic analysis of possible molecular mechanisms of normal and pathogenic genome rearrangements based on various G-quadruplexes as alternative precursor structures for recombination or gene conversion, thereby identifying a structural motif that exhibits similarity between the human intronic G-quadruplex and the active site of group I intron (Kuryavyi and Patel, 2010), as well as invoking parallel-stranded crossing-over mediated by a novel dimeric G-quadruplex formed by the c-kit-2 intergenic region (Kuryavyi et al., 2010).

Here, we present solution structures of monomeric and 5´-end-stacked dimeric G-quadruplexes formed by the N. gonorrhoeae pilE G4 sequence (5´-G3TG3TTG3TG3) in monovalent cation solution. We show that the pilE G-quadruplex binds to Escherichia coli RecA with affinity similar to single-stranded DNA but does not bind other G-quadruplex structures. We also show that the pilE G-quadruplex can promote E. coli RecA mediated strand exchange. In addition, we hypothesize how interactions between RecA and monomeric pilE G-quadruplex could facilitate the specialized recombination reactions leading to pilin diversification.

RESULTS

Impact of the 5´-Prefix Sequence on G-Quadruplex Formation

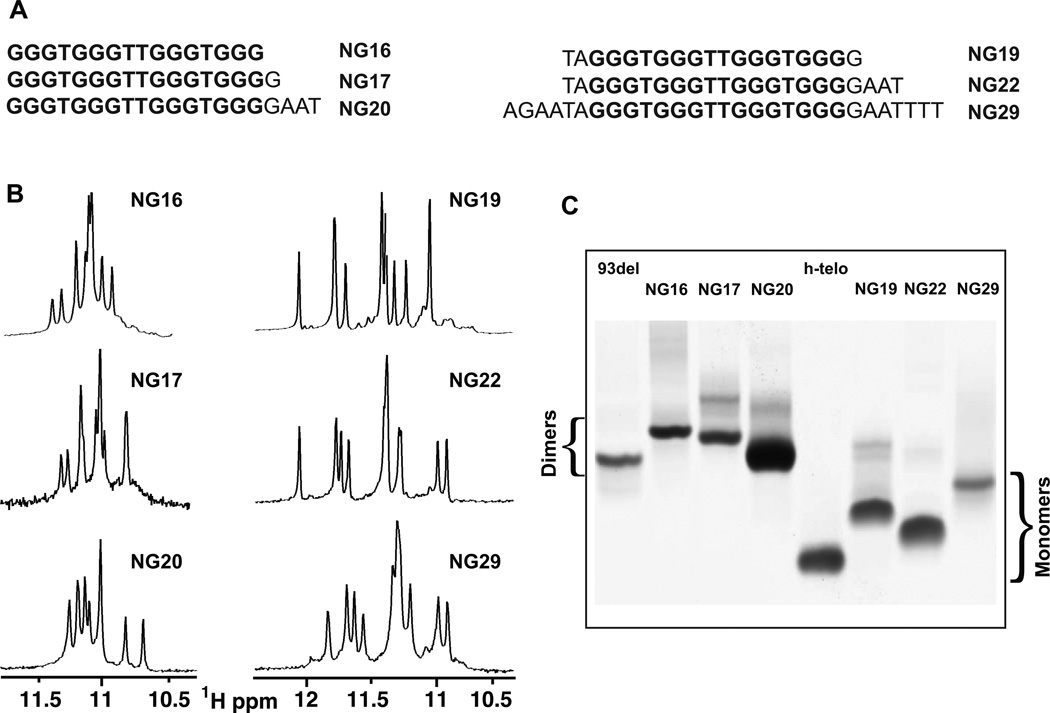

The N. gonorrhoeae pilE G4 sequence is essential for pilin antigenic variation and is located upstream of pilE in the gonococcal genome (Cahoon and Seifert, 2009). The pilE G4 16-mer sequence (5´-G3TG3TTG3TG3) exhibits perfect mirror symmetry centered between two central T residues (NG16, Figure 1A). One extra G nucleotide at the 3´-end (NG17), as well as AT-containing segments at one or both ends (NG19, NG20, NG22 and NG29), breaks this symmetry (Figure 1A). We have systematically recorded NMR spectra of sequences NG16 through NG29 (Figure 1A) in monovalent cation solution, so as to investigate the effect of flanking sequences on G-quadruplex formation by the 5´-G3TG3TTG3TG3 pilE G4 sequence. We observed two distinct imino proton spectral patterns as a function of flanking sequence between 10.5 and 12.0 ppm (Figure 1B), a region characteristic of guanine imino protons involved in G•G•G•G tetrad formation.

Figure 1. pilE G4 DNA Oligomer Sequences Used in the Current Study, Their Imino Proton NMR Spectra and Their Mobilities in Native PAGE.

(A) pilE G4 DNA oligomers starting with 5´G: NG16, NG17 and NG20 (left), and those containing a 5´-prefix: NG19, NG22, NG29 (right). The core segment is highlighted in bold lettering.

(B) Imino proton NMR spectra of above listed DNA oligomers in 100 mM KCl, 5mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C.

(C) Electrophoretic mobilities of dimeric NG16 NG17 and NG20 and monomeric NG19, NG22 and NG29 pilE G4 sequences are compared with dimeric 93del (Phan et al., 2005b) and monomeric human telomere (Phan et al., 2007b) G-quadruplex markers in 25% acrylamide gel with 25 mM KCl at 4°C.

One spectral pattern, adopted by NG19, NG22 and NG29 sequences (Figure 1A), exhibits guanine imino proton resonances dispersed over a wide spectral range between 10.7 and 12.2 ppm (Figure 1B, right panel). The other spectral pattern, adopted by NG16, NG17 and NG20 sequences (Figure 1A), exhibits partially overlapping guanine imino proton resonances dispersed over a narrower spectral range between 10.6 and 11.5 ppm (Figure 1B, left panel). The essential defining characteristic between the two imino proton spectral patterns for the listed DNA sequences is their 5´-end prefix: NG16, NG17, and NG20 all begin with the 5´-G residue of 5´-G3TG3TTG3TG3, whereas the remaining sequences tested have extra bases at their 5´-end: 5´-TA in NG19 and NG22, and 5´-AGAATA in NG29 (Figure 1A). Contrary to the profound impact of residues at the 5´-end, addition of residues at the 3´-end, have no impact on either of the two distinct guanine imino proton spectral patterns (Figure 1B).

We have monitored the native gel electrophoresis migration patterns of various pilE G4-containing DNA oligomers (NG16 to NG29) so as to elucidate the oligomeric state of these sequences that exhibit the two distinct guanine imino proton spectral patterns (Figure 1B). The DNA oligomers that begin with a 5´-G residue (NG16, NG17 and NG20) and exhibited a narrower imino proton spectral pattern (Figure 1B, left panel), migrated as dimers in both K+ (Figure 1C) and Na+ (data not shown) cation-containing solution, while those that had extra bases at the 5´-end (NG19, NG22 and NG29) exhibited a more dispersed imino proton spectral pattern (Figure 1B, right panel), migrated predominantly as monomers (Figure 1C). Molecularity based on gel migration has its limitations, since molecular shape, net charge and dangling ends can impact on mobility of G-quadruplexes. The gel migration of dimeric NG29 G-quadruplex is at the border of monomeric and dimeric G-quaruplexes and this could reflect the contributions of 6-nt dangling 5’- and 3’-ends on either side of the G-quadruplex fold for this sequence.

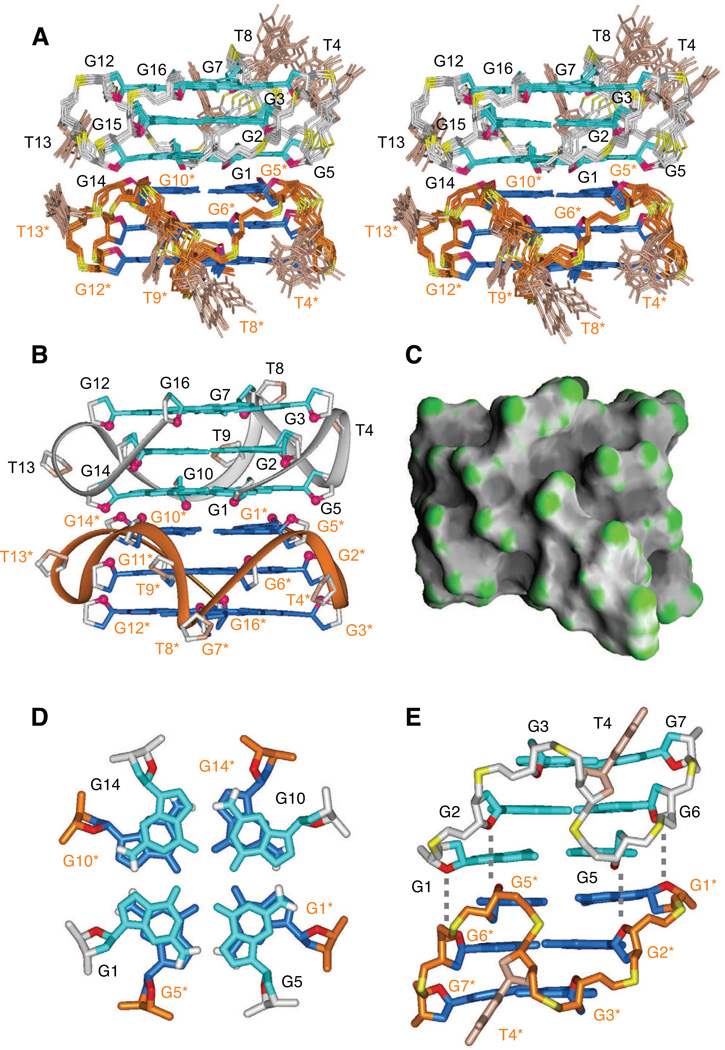

Proton NMR Assignments of NG19 and NG22 pilE G4 Sequences

The numbering system for the NG19 and NG22 sequences are as follows:

5´-T1AGGG5TGGGT10TGGGT15GGGG-3´

5´-T1AGGG5TGGGT10TGGGT15GGGGA20AT-3´

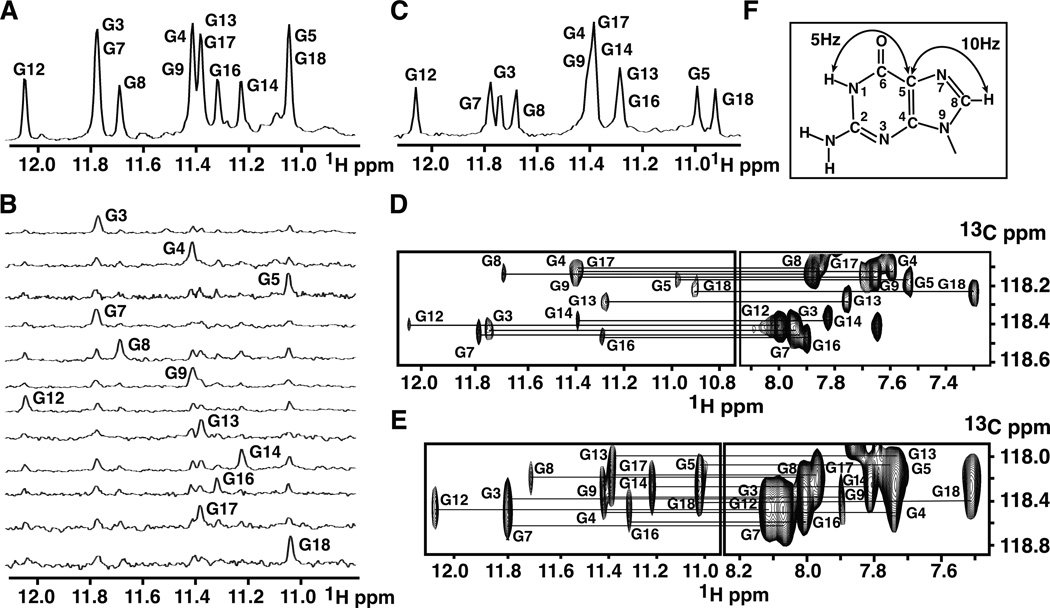

with the 16-mer core segment highlighted in bold. We observe 12 imino protons between 11.0 and 12.1 ppm in the exchangeable proton NMR spectrum of the NG19 sequence in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM K-phosphate, H2O, pH 6.8, at 25 C, in a spectral range characteristic of guanine imino protons involved in N-H••O hydrogen bond formation, a feature characteristic of G-tetrad formation (Figure 2A) [reviewed in (Patel et al., 2007)]. We observe doubling of intensity for proton chemical shifts of four peaks (at 11.78, 11.42, 11.38, and 11.05 ppm), reflective of spectral overlap at these positions. We have made unambiguous site-specific guanine imino proton assignments by recording 15N-filtered imino proton NMR spectra on samples containing 2% uniformly 15N,13C-labeled guanines at the indicated positions (Figure 2B). The resulting imino proton assignments are listed above the control NMR spectrum of the NG19 sequence in Figure 2A, with chemical shift overlap observed for four pairs (G3/G7, G4/G9, G13/G17, and G5/G18) of imino protons.

Figure 2. Exchangeable Proton NMR Spectra and Proton Assignments of Monomeric NG19 and NG22 pilE G4 Sequences.

(A) Imino proton NMR spectrum of NG19 sequence (0.7 mM strands) in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. Imino proton assignments are listed over the spectrum.

(B) Imino protons of NG19 sequence were assigned in 15N-filtered NMR spectra of samples containing 2% uniformly-15N,13C-labeled guanines at the indicated positions.

(C) Imino proton NMR spectrum of NG22 sequence .8 mM strands) in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. Imino proton assignments were established by selective labeling, as well as comparison with assignments of the imino proton spectrum of the NG19 sequence.

(D) Guanine H8 proton assignments of NG22 sequence (6 mM strands) based on through-bond correlations between assigned imino and to be assigned H8 protons via 13C5 at natural abundance, using long-range J couplings shown in panel F.

(E) Guanine H8 proton assignments of NG19 sequence (1.7 mM strands) using assignment protocol as outlined in panel D.

(F) A schematic drawing indicating long-range J couplings used to correlate imino and H8 protons within the guanine base.

The corresponding imino proton spectrum of the NG22 sequence is shown in Figure 2C, with assignments based on a subset of labeling experiments, listed over the spectrum. This spectrum exhibits resolved imino proton chemical shifts for G3 and G7, as well as for G5 and G18 (Figure 2C), thereby resolving part of the assignment ambiguity due to spectral overlap. The imino protons were next correlated with their assigned H8 protons within individual guanines based on through bond correlations via 13C at natural abundance for both the NG22 (Figures 2D) and NG19 (Figure 2E) sequences, using long-rang J couplings shown schematically in Figure 2F (Phan, 2000; Phan and Patel, 2002). Such an approach, combining data for both NG19 (Figures 2A and 2E) and NG22 (Figures 2C and 2D) sequences, resolved overlap ambiguities and provided guanine imino proton and H8 assignments for both sequences.

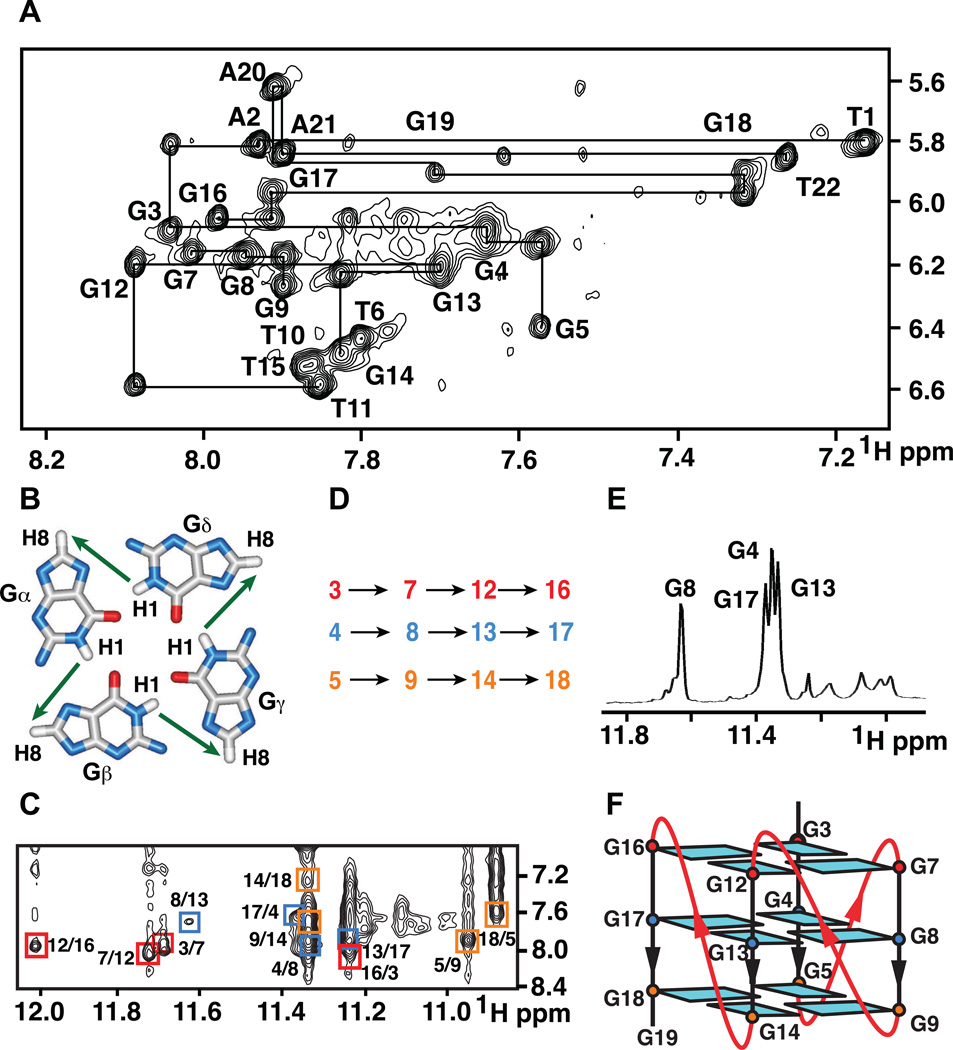

We next traced NOE´s between base protons and their own 5´-flanking sugar H1´ protons in an expanded NOESY contour plot (250 ms mixing time) for the NG22 sequence in 2H2O buffer solution (Figure 3A), thereby yielding base and sugar H1´ proton assignments. The remaining sugar protons were next assigned by through-bond COSY and TOCSY experiments, with base and sugar proton chemical shifts listed in Table S1. We did not observe strong NOE´s between base and sugar H1´ protons at short (50 ms) mixing times, indicative of anti torsion angles (Patel et al., 1982) for all guanines of the NG22 sequence.

Figure 3. NOESY Contour Plots of NG22 pilE G4 Sequence in K+ Solution in 2H2O and H2O, Hydrogen-deuterium Exchange of Monomeric NG19 pilE G4 Sequence and Schematic Representation of Monomeric pilE G-quadruplex Fold.

(A) Expanded NOESY contour plot (250 ms mixing time) correlating base and sugar H1´ non-exchangeable protons of NG22 sequence (1.7 mM strands) in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. The lines trace NOEs between base protons (H8 or H6) and their own and 5´-flanking sugar H1´ protons. Intra-residue base to sugar H1´ NOEs are labeled with residue numbers.

(B) Schematic of guanine imino-guanine H8 connectivities around a G-tetrad.

(C) Expanded NOESY contour plot (mixing time: 250 ms) showing imino to H8 connectivities of NG22 sequence (1.7 mM strands) in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM K-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. Cross-peaks identifying connectivities within individual G-tetrads are color-coded, with each cross-peak framed and labeled with the residue number of imino proton in the first position and that of the H8 proton in the second position.

(D) Guanine imino-guanine H8 connectivities observed for G3•G7•G12•G16 (red), G4•G8•G13•G17 (blue), and G5•G9•G14•G18 (orange) G-tetrads.

(E) Imino proton NMR spectrum of monomeric NG19 sequence form recorded 1 hr following transfer from H2O (after lyophilization) to 2H2O solution. Assignments of slowly exchanging imino protons are listed over the spectrum.

(F) Schematic representation of the all-parallel-stranded monomeric NG19 pilE G-quadruplex fold. Anti bases are indicated in cyan and loop connectivities shown by red lines.

Monomeric G-quadruplex Fold of NG22 pilE G4 Sequence

The observation of 12 guanine imino protons between 11.0 and 12.2 ppm in the NG22 sequence spectrum (Figure 2C) is consistent with G-quadruplex formation stabilized by three stacked G-tetrads. We have assigned guanines within each of the three G-tetrads by monitoring NOE´s between assigned guanine imino and H8 protons around individual G-tetrad planes (shown schematically Figure 3B) in the expanded NOESY spectrum (mixing time 250 ms) of the NG22 quadruplex in 2H2O buffer solution (Figure 3C). The observed imino-H8 NOE connectivities (Figure 3C) identify formation of G3•G7•G12•G16 (assignments in red), G4•G8•G13•G17 (assignments in blue) and G5•G9•G14•G18 (assignments in orange) G-tetrads (Figure 3D).

We also observe four slowly exchanging guanine imino protons, assignable to G4, G8, G13 and G17, in the imino proton spectrum of NG22 recorded 40 min following transfer from 100 mM KCl, 5 mM phosphate, H2O solution (after lyophilization) to its 2H2O counterpart (Figure 3E). Since the imino protons of the G4•G8•G13•G17 G-tetrad exhibit the slowest exchange rates (Figure 3E), this G-tetrad must constitute the middle layer of the monomeric G-quadruplex, thereby defining the fold shown in Figures 3F. All guanines adopt anti glycosidic torsion angles and all three loops are of the double-chainreversal type (Wang and Patel, 1994) for the deciphered fold of the monomeric NG22 G-quadruplex (Figure 3F).

We did note that the NOE walk (Figure 3A) could be monitored for 5´-end TA and 3´-end GAAT segments, suggestive of a helical-like arrangement at both ends. By contrast, the NOE walk was interrupted at G5-T6-G7, G9-T10 and G14-T15-G16 steps (Figure 3A), suggestive that these thymines, connecting GGG tracts, that are part of the double-chain-reversal loops, were most likely extruded out of the monomeric G-quadruplex fold (Figure 3F).

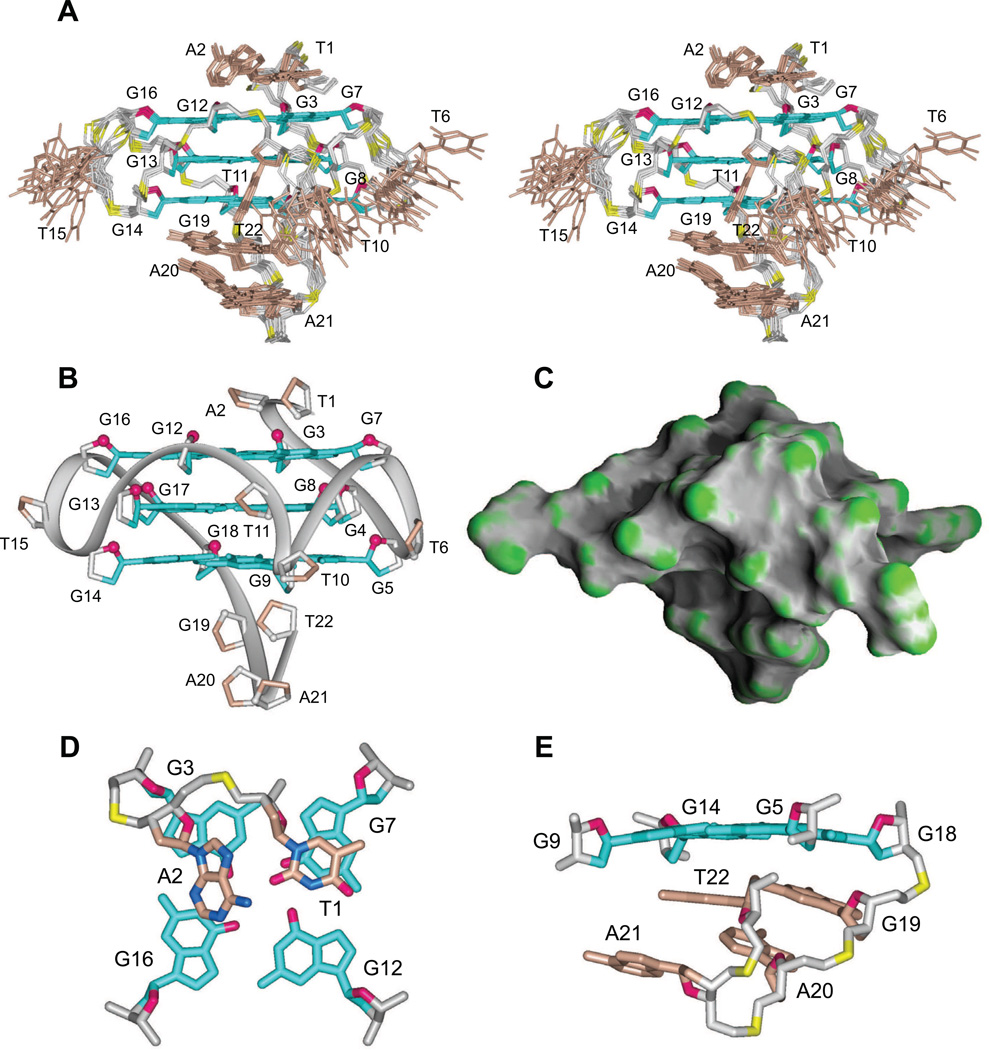

Solution Structure of the Monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex

Initial distance-restrained and subsequent intensity-restrained molecular dynamics calculations of the solution structure of monomeric pilE NG22 G-quadruplex were guided by exchangeable and non-exchangeable proton restraints (numbers listed by category in Table S2). The ensemble of 12 refined superpositioned structures is shown in stereo (Figure 4A), with a representative refined structure in the same orientation shown in ribbon (Figure 4B) and surface (Figure 4C) representations. The ensemble of refined structures is well converged, exhibiting pairwise rmsd values for the stacked G-tetrad core in the 0.44 Å range (Table S2).

Figure 4. Solution Structure of the Monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex in K+ solution.

(A) Stereo view of 12 superpositioned refined structures of the monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex. Guanine bases in the G-tetrad core are colored cyan (anti). Bases in connecting loops, and in 5´ and 3´ elements are shown in brown, with the backbones in grey, sugar ring oxygens in red and phosphorus atoms in yellow.

(B) Ribbon representation of a representative refined structure of the monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex.

(C) Surface representation of a representative refined structure of the monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex.

(D) Platform stacking of the 5´-TA prefix dinucleotide over the 5´-tetrad.

(E) Base alignment within the four-residue C19-A20-A21-T22 3´-hook element. See also Figure S1.

The first and the third single-residue loops are of the double-chainreversal type, with T6 and T15 nucleotides directed out of the groove. However, T6 is positioned closer to the wall of the groove and inclined towards residue T10 from the neighboring loop (Figures 4A and S1B, D). The second loop is also of the double-chain-reversal type, but is composed of two nucleotides, T10 and T11. Residue T10 turns towards the neighboring groove (Figures 4A and S1A), while residue T11 is fixed by hydrogen-bond formation between atom O2 of T11 and amino proton of G8 (Figure S1A) inside the groove formed by the G7-G8-G9 and G12-G13-G14 columns.

Surprisingly, the 5´-TA overhang caps the top G3•G7•G12•G16 tetrad layer, forming a T-A platform (Cate et al., 1996), with the residue A2 inclined out of plane (Figures 4A, D). We also observe an unanticipated topology for the single-stranded overhang at the 3´-end of the all-parallel-stranded monomeric pilE G-quadruplex fold. The G19-A20-A21-T22 segment makes a sharp turn at the junction between A20 and A21, bringing T22 in proximity with the bottom G5•G9•G14•G18 tetrad (Figures 4A, E). We observe NOE´s between the methyl protons of T22 and imino protons of G5 and G9, between H6 of T22 and imino proton of G5, between the methyl proton of T22 and H1´ sugar proton of G9, and between H1´ sugar proton of T22 and imino proton of G5. These NOE´s, along with intra- and inter-residue NOE´s observed for other residues within the G19-T22 segment, define a unique ‘3´-hook’ configuration, with no hydrogen bond interactions between its constitutive nucleotides (Figures 4A, B, E).

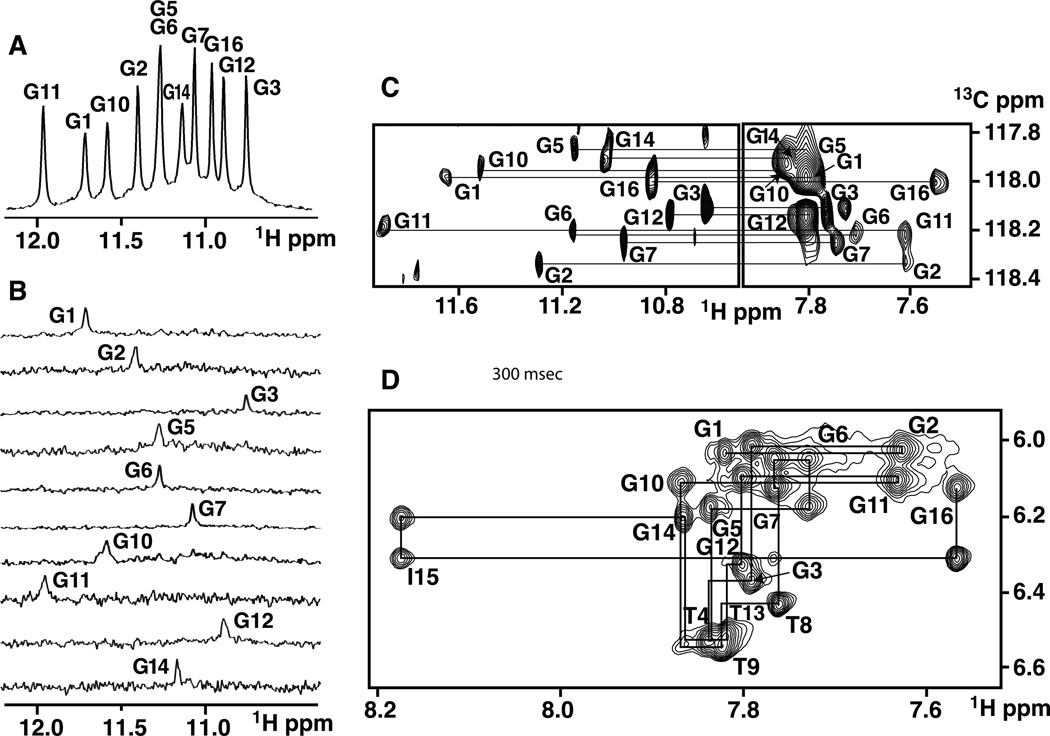

Proton NMR Assignments of NG16 pilE G4 Sequence

The N. gonorrhoeae pilE G4 symmetric 16-mer core sequence,

5´-G1GGTG5GGTTG10GGTGG15G-3´

labeled NG16, migrates in native gel electrophoresis as a dimer, both in K+ (Figure 1C) and Na+ containing solution. The imino proton NMR spectra of NG16 have been recorded in both K+- and Na+-containing solution. Since single inosine for guanine substitutions have been shown to enhance the resolution of both imino and aromatic protons, we substituted I15 for G15 in NG16 with resultant improvement in spectral quality, for spectra recorded in Na+ cation-containing solution (Figure 5A). We observe eleven imino protons between 10.5 and 12.0 ppm in Figure 5A (the downfield shifted I15 imino proton is outside this range), requiring that the dimer be composed of two symmetry-related monomers. We assigned the guanine imino protons following site-specific incorporation of 2% 15N-labeled-guanines one at a time into the I15-modified NG16 sequence and recorded 15N-filtered imino proton NMR spectra (Figures 5B) (Phan and Patel, 2002) which yielded the assignments listed over the NMR spectrum in Figure 5A. The guanine H8 protons were next linked through long-range through-bond J-coupling experiments to the assigned guanine imino protons (Phan, 2000) as shown in Figure 5C, with the exception of I15, whose H8 proton stands out due its significantly downfield shifted position.

Figure 5. Exchangeable Proton NMR Spectra and Proton Assignments of Dimeric I15-modified NG16 pilE G4 Sequence.

(A) Imino proton spectrum of I15-modified NG16 sequence (0.3 mM strands) in 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. Unambiguous imino proton assignments are listed over the spectrum.

(B) Imino protons of I15-modified NG16 sequence were assigned in 15N-filtered NMR spectra of samples containing 2% uniformly-15N,13C-labeled guanines at the indicated positions.

(C) Guanine H8 proton assignments of I15-modified NG16 sequence (3.5 mM strands) based on through-bond correlations between assigned imino and to be assigned H8 protons via 13C5 at natural abundance, using long-range J couplings shown in Figure 2, panel F.

(D) Expanded NOESY contour plot (300 ms mixing time) correlating base and sugar H1´ non-exchangeable proton assignments of I15-modified NG16 sequence (1.7 mM strands) in 100 +mM NaCl, 5 mM Na-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. The line connectivities trace NOEs between base protons (H8 or H6) and their own and 5´-flanking sugar H1´ protons. Intra-residue base to sugar H1´ NOE’s are labeled with residue numbers.

The expanded NOESY contour plot (300 ms mixing time) correlating base and sugar H1´ protons of I15-modifed NG16 is plotted in Figure 5D, together with tracing of NOE connectivities between the base protons and their own and 5´-flanking sugar H1´ protons. The remaining sugar protons of I15-modified NG16 were assigned by through-bond COSY and TOCSY experiments, with chemical shifts listed in Table S3.

All residues of I15-modified NG16 show comparable intensities for their base to H1´ NOE´s at short 50 msec mixing time (data not shown), implying that all glycosidic torsions are anti. All T-residues, except at the T9-G10 step, do not show sequential connectivity to 5´-neighboring residues (Figure 5D).

Dimeric G-quadruplex Fold of NG16 pilE G4 Sequence

We have assigned guanines to specific G-tetrads by monitoring NOE’s between guanine imino and H8 protons around individual G-tetrad planes (Figures 6A, B, C) in the NOESY spectrum (mixing time 250 ms) of the dimeric I15-modified NG16 pilE G4 sequence. These studies allow identification of a G-quadruplex fold composed of G3•G7•G12•G16, G2•G6•G11•I15 and G1•G5•G10•G14 G-tetrads for each monomer within the dimer.

Figure 6. NOESY Contour Plots of I15-modified NG16 pilE G4 Sequence in Na+ Solution in H2O, Hydrogen-deuterium Exchange and Schematic Representation of 5’-end Stacked Dimeric pilE G-quadruplex Fold.

(A) Expanded NOESY contour plot (mixing time: 250 ms) showing imino to H8 connectivities of I15-modified NG16 sequence (3.5 mM strands) in 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na-phosphate buffer, pH 6.8 at 25 °C. Cross-peaks identifying connectivities within individual G-tetrads are color-coded, with each cross-peak framed and labeled with the residue number of imino proton in the first position and that of the H8 proton in the second position.

(B) Guanine imino-guanine H8 connectivities around a G-tetrad.

(C) Guanine imino-guanine H8 connectivities observed for G1•G5•G10•G14 (red), G2•G6•G11•G15 (green) and G3•G7•G12•G16 (orange) G-tetrads.

(D) Imino proton spectrum of I15-modified NG16 sequence dimeric form recorded 5 min and 30 hr following transfer from 2H2O (after lyophilization from 2H2O solution) to H2O solution. Assignments of fast exchanging imino protons are listed over the spectrum.

(E) Schematic representation of the 5’-end stacked all-parallel-stranded NG16 dimeric pilE G-quadruplex fold. Anti bases are indicated in cyan and connectivities shown by red and black lines for two monomers related by symmetry.

See also Figure S2.

We observed a very distinct proton to deuteron exchange pattern for the dimeric NG16 and I15-modified NG16 pilE G-quadruplexes. Four imino protons assigned to G3, G7, G12 and G16 exchanged rapidly upon dissolving a lyophylized NG16 sample into 2H2O, while the other eight protons remained inaccessible (Figure S2A) for several hours (data not shown). In a reverse experiment, after transfer of the deuterated I15-modified NG16 sample into H2O, we observed the rapid appearance of G3, G7, G12 and G16 imino proton signals (Figure 6D, top), with delayed gradual appearance of the remaining protons (Figure 6D, bottom) over a period of 6 hours, with protons fully substituting for deuterons after 30 hrs (Figure S2B).

The resulting dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex fold, which integrates electrophoretic mobility (Figure 1C), proton exchange (Figure 6D) and NMR spectral analysis (Figure 6A), is shown schematically in Figure 6E. Within this dimeric G-quadruplex, four imino protons of the outer G3•G7•G12•G16 G-tetrad (Figure 6E) exchange rapidly, while eight imino protons from the internal G2•G6•G11•G15 and inter-subunit stacked G1•G5•G10•G14 G-tetrads (Figure 6E) are protected from direct exchange with protons from the solvent.

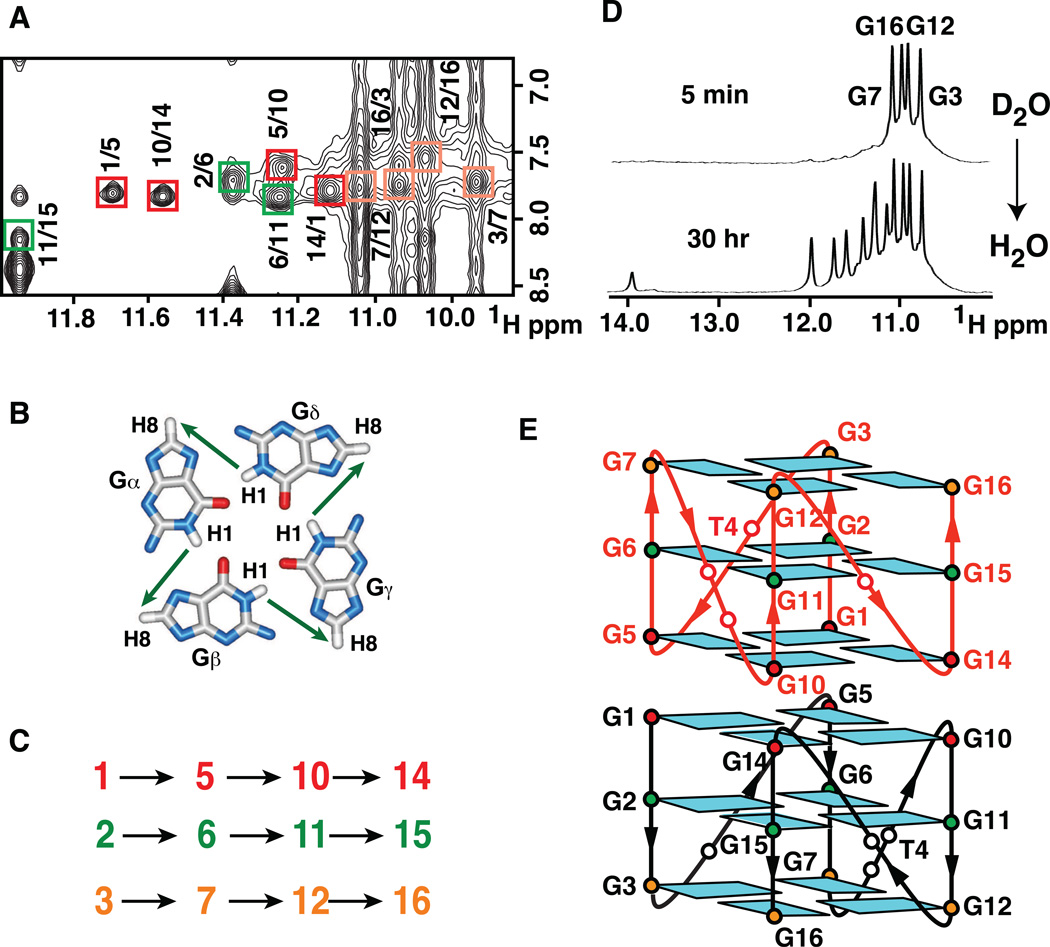

Solution Structure of the 5´-end-stacked Dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex

Initial distance-restrained and subsequent intensity-restrained molecular dynamics calculations of the solution structure of the dimeric I15-modified NG16 pilE G-quadruplex were guided by exchangeable and non-exchangeable proton restraints listed by category in Table S4. We observed good convergence within the 11 refined superpositioned structures (Figure 7A), with the ensemble exhibiting pairwise rmsd values in the 0.40 Å range for the stacked G-tetrad dimeric core component (Table S4). A representative refined structure of the dimeric G-quadruplex viewed in the same orientation is shown in Figure 7B and its surface representation is shown in Figure 7C.

Figure 7. Solution Structure of the NG16 Dimeric pilE G-quadruplex in Na+ Solution.

(A) Stereo view of 11 superpositioned refined structures of the 5’-end stacked dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex. Guanine bases in the G-tetrad core are colored cyan (anti). Bases in connecting loops are shown in brown, with the backbones of two individual monomers in grey and orange, sugar ring oxygens in red and phosphorus atoms in yellow.

(B) Ribbon representation of a representative refined structure of the 5’-end stacked dimeric pilE G-quadruplex.

(C) Surface representation of a representative refined structure of the 5’-end stacked dimeric pilE G-quadruplex.

(D) Stacking of two interfacial 5´-G-tetrads (G1•G5•G10•G14) between monomers in the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex.

(E) Side projection of the dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex, showing mutual alignment and twist of the T4-T4* residue-connected grooves.

We observe significant stacking overlap between guanines of the 5´-end stacked interfacial G1•G5•G10•G14 G-tetrads in the structure of the dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex (Figure 7D). In addition, T4 (Figures 7A, E) and T13 (Figure 7A) single linker residues are positioned in partially inward-pointing configurations and directed towards their grooves, with this orientation supported by observed NOE’s between loop residues (T4 or T13) and their neighboring residues.

The all-parallel-stranded stacked G-tetrad cores of individual monomeric units of the dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex (Figure 7A,B) are similar to their counterpart within the monomeric pilE NG22 G-quadruplex (Figure 4A,B).

Stacking Alignment of 5´-G-tetrads in the Dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex

We observe a set of NOE cross peaks between stacked interfacial G1•G5•G10•G14 G-tetrads that validate the 5´-end stacked arrangement of the two monomeric units that constitute the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex (Figure 7D). These include NOEs involving proton pairs G10(H1´)-G14(H1´), G1(H1´)-G5(H1´), G1(H1´)-G5(H8) and G5(H1´)-G1(H8) in the NOESY spectra of dimeric I15-modified NG16 G-quadruplex (Figure S2C).

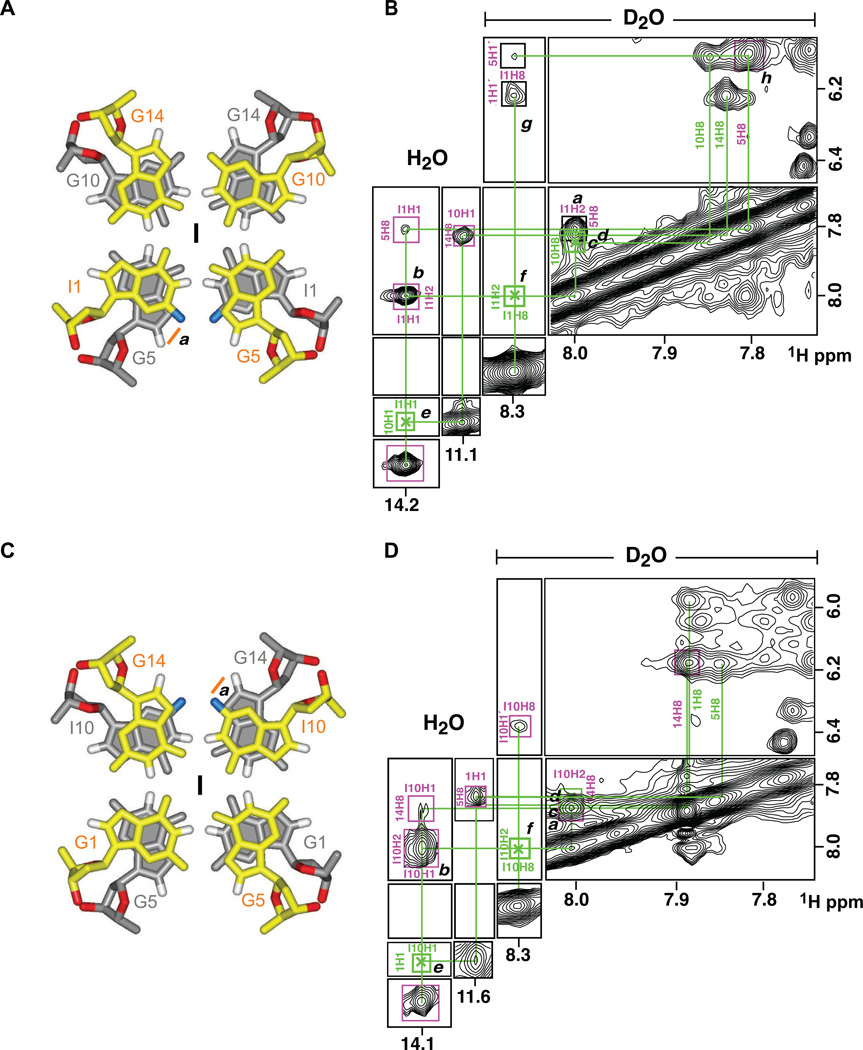

The unique 5´-stacking alignment of the dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex (Figure 7D) was further experimentally validated following analysis of NOE patterns for the dimeric I1- and I10-substituted NG16 pilE G-quadruplexes. Substitution of inosine (with its H2 proton) for guanine at the interfacial G1•G5•G10•G14 G-tetrad of NG16 result in characteristic NOE patterns that allow definitive differentiation between alternate stacking arrangements (Phan et al., 2005a). Because of the four-fold symmetry of the all-anti guanine tetrad, there are theoretically four rotational isomers involving stacked guanines possible at the dimeric interface.

For the I1 substituted NG16 dimeric pilE G-quadruplex, the H2 proton of I1 is predicted to show a NOE to the H8 proton of G5 in rotamer I (Figure 8A, labeled a), to the H8 proton of G10 in rotamer II (Figure S3A, labeled a), to the H8 proton of G14 in rotamer III (Figure S3B, labeled b) and the H8 proton of I1 in rotamer IV (Figure S3C, labeled c). Experimentally, we observe a strong NOE between the H2 proton of I1 and the H8 proton of G5 (peak a, Figure 8B), but not the H8 protons of G10, G14 and I1, strongly supporting the stacking alignment shown in rotamer 1 at the dimeric interface (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. Analysis of Interface Through NOE’s of Reporter Point Substitution of I1 for G1 and I10 for G10 for Rotamer I in the Dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex.

(A) Signature cross-peak of rotamer I in I1-substituted NG16 dimeric G-quadruplex marked a.

(B) Observed and expected NOE’s for four theoretically possible rotamers I to IV of I1-substituted NG16 dimeric G-quadruplex with NOE assignments listed in the contour plot.

(C) Signature cross-peak of rotamer I in I10-substituted dimeric NG16 .G-quadruplex marked b.

(D) Observed and expected NOE’s for four theoretically possible rotamers I to IV of I10-substituted dimeric NG16 G-quadruplex with NOE assignments listed in the contour plot.

Position of non-exchangeable H2 proton of I1 is colored blue in panel A and position of non-exchangeable H2 proton of I10 is colored blue in panel C. See also Figure S3.

For the I10 substituted NG16 dimeric pilE G-quadruplex, the H2 proton of I10 is predicted to show an NOE to the H8 proton of G14 in rotamer I (Figure 8C, labeled a), to the H8 proton of G1 in rotamer II (Figure S3D, labeled d), to the H8 proton of G5 in rotamer III (Figure S3E, labeled e) and the H8 proton of I10 in rotomer IV (Figure S3F, labeled F). Experimentally, we observe a strong NOE between the H2 proton of I10 and the H8 proton of G14 (peak a, Figure 8D), but not the H8 protons of G1, G5 and I10, strongly supporting the stacking alignment shown in rotamer 1 at the dimeric interface (Figure 8C).

The remaining cross peaks in the NOESY spectra of the I1-substituted (Figure 8B) and I10-substituted (Figure 8D) NG16 pilE G-quadruplexes have also been assigned and analyzed to insure that they are consistent with the stacking arrangement corresponding to rotamer I, and the exclusion of rotamers II, III and IV.

Alignment of Central TT Double-chain-reversal Loop

Loops containing G-tracts play critical roles in defining G-quadruplex topology (Guedin et al., 2010). Similar to what was observed in the monomeric pilE G-quadruplex fold (Figure 4A), the T8-T9 double chain reversal loop in the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex has the T9 residue positioned inside of the groove (Figure 7A), stabilized by hydrogen-bonding between the O2 atom of T9 and the aminoproton of G6. This alignment of T9 in the groove is supported by the following observed NOE´s: G10(H3´)-T9(H1´) (in I10-substituted spectrum), T9(H1´)-G10(H8, H2´, H1´) and T9(H4´)-G10(H5´) (in I15-substituted spectrum). The T8 residue is directed towards the 3´-neighboring groove (Figure 7A), similar to its counterpart in the monomeric pilE G-quadruplex structure.

Susceptibility of pilE G-Quadruplexes to S1 Nuclease

Current models of recombination mechanisms imply initial single- or double-strand breaks by nucleases and hence we were interested in the sensitivity to nuclease cleavage of connecting loops within G-quadruplex folds. Digestion of the monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex (in K+-cation containing solution) by S1 nuclease leads to formation of a ladder on a denaturing gel, with product lengths ranging between 16 and 22-nt (Figure S4A). After 30 min of reaction, the ladder clears out towards the product migrating as 16-nt, without observation of shorter products in the range of 8 to 12-nt . These results indicate that S1 nuclease digests single-stranded overhangs of the monomeric pilE G-quadruplex, but does not cut into its core composed of three stacked G-tetrads.

Surprisingly, digestion of the NG16 dimeric pilE G-quadruplex results in two oligonucleotide bands migrating approximately as 7-mers and 3-mers (Figure S4B). The intensity of the original 16-mer gradually decreases as a function of the reaction time at two tested (0.2 and 0.4 mM) DNA concentrations. Thus the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex serves as a substrate of S1 nuclease, and unexpectedly is digested within the G-tetrad core.

Binding of the Monomeric pilE G-Quadruplex to RecA

In N. gonorrhoeae, recombination events which occur at pilE and result in a new pilin antigenic variant are dependent on RecA (Koomey et al., 1987). Since pilin antigenic variation initiates at the pilE G4 sequence, we investigated whether RecA could bind to monomeric pilE G-quadruplex, thereby effectively catalyzing pilin antigenic variation in N. gonorrhoeae (Stohl et al., 2002). RecA has been shown to bind and assemble on ssDNA and dsDNA in filaments of 3-nucleotide unit increments (Figures 9A and S5A) (Chen et al., 2008). Because the monomeric G-quadruplex unit is composed of three stacked G-tetrads (Figure 3F), we postulated that the all-parallel-stranded monomeric pilE G-quadruplex might fit into the three-nucleotide binding site of a monomeric RecA unit (Chen et al., 2008). The amino acid sequences of RecA proteins from N. gonorrhoeae (RecANg) and E. coli (RecAEc) exhibit 81% similarity and 65% identity and the E. coli RecA can mediate pilin antigenic variation in N. gonorrhoeae (Stohl 2002) (Stohl et al., 2011). The RecA IGVMFGNP-motif, which constitutes the loop that separates DNA into three-nucleotide segments in RecAEc-DNA complex, is identical in both proteins, except for a single substitution of Asn (in RecAEc) by Ser (in RecANg). Therefore, the two proteins are expected to be rather similar in their structure and mechanism of action.

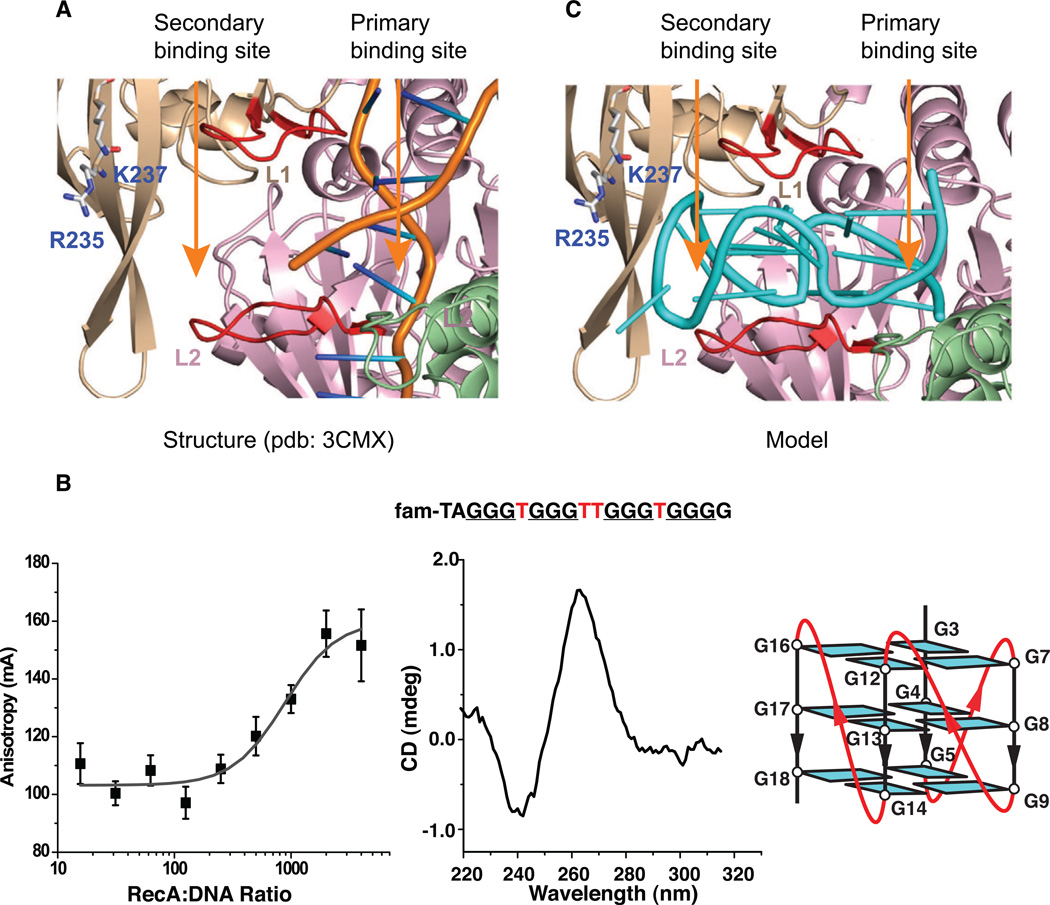

Figure 9. Ribbon Representations of X-ray Structure of RecA in Complex with DNA, and Binding Studies and Model of RecA bound by a Monomeric pilE G-quadruplex.

(A) Ribbon view of dsDNA bound after strand exchange in the primary binding site of RecA filament (PDB: 3CMU). Three bases of dsDNA are separated between two loops, L1 and L2, colored red.

(B) Left panel: Flourescence Anisotropy (FA) measurements of RecA binding to N. gonorrhoeae monomeric pilE G-quadruplex sequence in K+ solution with apparent Kd = 0.88 0± 0.31 µM. 5´-FAM-labeled pilE G-quadruplex sequence (top) with loop elements highlighted in red. Middle panel: Circular Dichroism (CD) spectrum of pilE G-quadruplex in K+ solution; Right panel: Schematic representation of the three-layered all-parallel-stranded monomeric pilE G-quadruplex with single residue loops.

(C) Ribbon view of model of monomeric pilE G-quadruplex bound to primary and secondary binding sites of RecA filament.

See also Figures S5 and S6.

Fluorescence anisotropy was used to measure the affinity of E. coli RecA for different G-quadruplex-forming G-rich DNA substrates. RecA binds NG19- like monomeric G-quadruplexes in monovalent cation solution with Kd = 0.88 + 0.31 µM (Figure 9B), with this binding affinitiy comparable to that for RecA binding to oligo dT16 (Kd = 0.64 + 0.26 µM) (Figure S6A). Interestingly, a three-layered G-quadruplex containing a single residue (minimal size) double-chain reversal loop (Figure 9B, right panel) is a prerequisite for binding in K+ solution, since three-layered G-quadruplexes containing two or three residue double-chain-reversal loops, formed by two other G-quadruplex sequences within the gonoccocal genome, do not bind RecA in K+ solution (Figure S6B and data not shown). These latter G-quadruplex forming sequences were not able to substitute for the pilE G4 sequence to restore pilin antigenic variation (Cahoon and Seifert, 2009). In addition, the number of stacked G-tetrads involved in G-quadruplex formation is also critical for binding, because a four-layered G-quadruplex (Smith et al., 1995; Wang and Patel, 1995) does not show affinity for RecA in K+ solution and cannot substitute for the pilE G4 sequence to restore pilin antigenic variation (Figure S6C and data not shown). In addition, the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex composed of six stacked G-tetrad layers (Fig. 6E), also does not bind RecA (Figure S6D).

Modeling studies based on the crystal structure of the RecA-dsDNA complex (Figures 9A and S5A) (Chen et al., 2008) establish that the three-layered all-parallel-stranded G-quadruplex containing single-residue double-chain-reversal loops (Figures 4A) can be positioned in a unique alignment within the RecA monomeric unit, with the no-residue groove and single-residue loops facing the enzyme-binding pocket, while the double-residue loop points outward (Figures 9C and S5B). By contrast, the same three-layered allparallel-stranded G-quadruplex with grooves connected by two or three residue double-chain-reversal loops (topology shown in Figure S6B, right panel), would clash with the RecA binding pocket, as would a four-layered G-quadruplex (Smith et al., 1995; Wang and Patel, 1995) (topology shown in Figure S6C, right panel). These data show that some but not all G-quadruplex structures can bind to RecA.

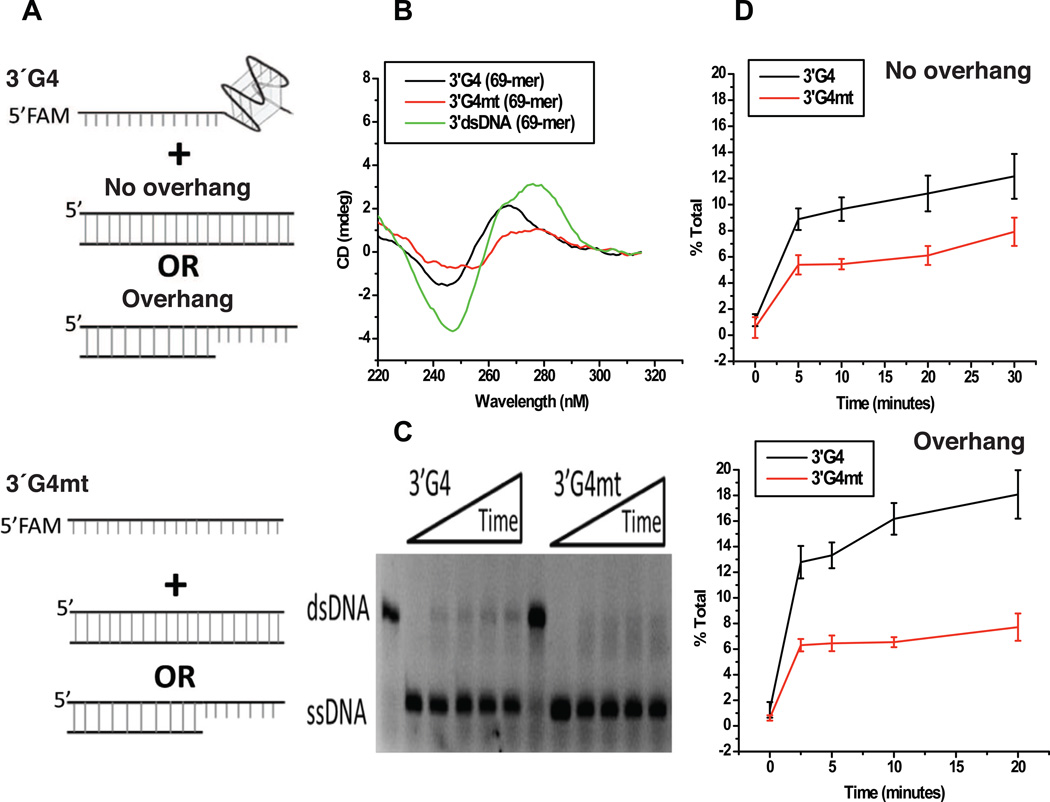

Strand Exchange Reaction Mediated by Monomeric pilE G-Quadruplex and RecA

The N. gonorrhoeae monomeric pilE G-quadruplex fits well in the space of the two DNA binding sites (Figures 9C and S5B). Once formed as a bead on a single-stranded DNA, the pilE G-quadruplex could perhaps produce a seeding point for RecA binding and increase the efficiency of RecA mediated strand exchange. To test this hypothesis, a series of oligonucleotides were synthesized (listed in Supplementary Table S5) either having the G-quadruplex (simplified designation as G4 in Figures 10 and S7) sequence or a mutated G4 sequence on either the 3’-end (Figure 10A) or 5’-end (Figure S7A). These oligomers were first determined to form ssDNA, dsDNA or G-quadruplex DNA by CD spectroscopy (Figures 10B and S7B) and were then tested for RecA-mediated strand exchange (Figures 10C and S7C). Oligomers having a G-quadruplex structure showed more efficient strand exchange than a version of the oligomer where that G-rich sequence was mutated and could not form the G-quadruplex structure (Figures 10D and S7D). These results suggest that the monomeric pilE G-quadruplex structure may recruit RecA and facilitate strand exchange during pilin antigenic variation.

Figure 10. A 3’pilEG4 Structure Promotes More Efficient RecA-mediated Strand Exchange.

(A) RecA strand exchange reaction schematic. A 5’FAM-labeled 69-mer containing a 3’ pilE G4 structure (3’G4) or the same 69-mer with a mutated pilE G4 sequence that can no longer form the structure (3’G4mt) was combined with dsDNA of the same length and sequence with or without an overhang containing the pilE G4 sequence.

(B) CD spectra of the 5’ FAM-labeled G4 (black) or G4 mutant sequence (red), and unlabeled dsDNA (green).

(C) RecA strand exchange. Shown is a representative 12% polyacrylamide gel of RecA strand exchange reactions performed with the 5’FAM-labeled 3’G4 or 3’G4mt sequence. (D) The percent total of RecA mediated strand exchange is plotted versus time. The 3’G4 (black) and 3’G4mt (red) combined with dsDNA without or with an overhang.

See also Figure S7.

DISCUSSION

All-parallel-stranded G-quadruplexes

The propensity of the pilE G4 sequence to adopt an all-parallel-stranded monomeric and dimeric G-quadruplexes highlights the importance of this all-parallel-stranded topology first identified for the human telomere by crystal structure determination (Parkinson et al., 2002) and in solution (Phan et al., 2007b) and subsequently observed for the c-myc sequence (Ambrus et al., 2005; Phan et al., 2004) in solution, as well as other sequences containing short linkers spanning G-tract segments [reviewed in (Burge et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2007)]. In addition, the identification of a 5´-end stacked all-parallel-stranded dimeric pilE G-quadruplex (Figure 6E) provides insights not only into the principles of G-tetrad stacking at dimeric interfaces, but also into the assembly of higher-order G-quadruplexes and the principles underlying their recognition.

Unique 5´- and 3´-End Features of the Monomeric pilE G-quadruplex

We have observed a two-residue overhang at the 5´-end that forms a T-A platform (Figures 4A, D), which caps the 5´ G-tetrad of the monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex. Previous structural studies have identified capped ends of G-quadruplexes, whereby T-A, C-A and A-A platforms form triads (Kuryavyi and Jovin, 1995) by a hydrogen-bonding interaction with a third base (Kettani et al., 2000a; Kettani et al., 1997; Kuryavyi et al., 2000). In the present work, the TA platform has no interacting hydrogen bonds to a third base, thus establishing that stacking between a platform and a G-tetrad constitutes an energetically stabilizing interaction. We postulate that the O2 atom of T1 could be involved in monovalent cation coordination in the center of the top G-tetrad, which could enhance the stability of unpaired residues T1 and A2 in a platform configuration. Further, formation of this platform prevents dimerization of two monomeric G-quadruplexes by stacking of their 5´-terminal G-tetrads, thereby explaining the role of the 5´-overhang in the observed switching between monomeric and dimeric pilE G-quadruplexes.

An unexpected snap-back topology was also observed at the 3´-end of the structure of the monomeric NG22 pilE G-quadruplex (Figure 4B), where the four-base single-stranded overhang (G19-A20-A21-T22) forms a reverse turn, such that its terminal T22 residue is positioned for stacking over the 3´-end G-tetrad (Figure 4E). We anticipate that potential involvement of T22 in cation coordination, together with the propensity for hydrogen bond formation between its O2 atom and amino proton of G19 and the hydrodynamic advantage of a compact 3´-end, most likely combine to define the structure of the ‘3´-hook’ configuration of the G19-A20-A21-T22 overhang segment (Figure 4E). This 3´-end topology contrasts with the snap-back feature observed for c-myc and c-kit1 monomeric G-quadruplexes whereby 3´-end G-residue(s) participate in completion of 3´-terminal G-tetrad(s) formation (Phan et al., 2007a; Phan et al., 2005a). The structure of the monomeric .pilE G-quadruplex illustrates how a G-quadruplex core could serve as a long-range coordination center for optimal positioning of a single-stranded overhang at the 3´-end.

A 5´-end Stacked Dimeric pilE G-quadruplex

A notable feature of the structure of the dimeric NG16 pilE G-quadruplex (Figures 7A, B) involves end-on-end stacking of two monomeric allparallel-stranded three-layered G-quadruplexes through their 5´-end G-tetrads. The purine six-membered rings overlap with each other, while the purine five-membered rings overlap with amino groups of guanine bases, thereby resulting in a very large stacking area at the interface (Figure 7D). For this interface overlap geometry, sugar residues are shifted by one step of helical twist, such as that observed in a side projection (Figure 7E), whereby the first G-tetrad tier residues G1/G1* become vertically aligned with residues G6*/G6 from the second G-tetrad tier of the symmetry-related monomer, with the same assignments also observed for the G5/G2* and G5*/G2 pairs.

The two monomeric components are positioned so as to achieve the overall second-order rotational symmetry of the resulting dimeric pilE G-quadruplex. There are four types of grooves associated with each monomeric G-quadruplex, with single-reside linkers spanning two of the grooves, a two-residue linker spanning a third groove, and no residue positioned within the remaining 5´–3´ groove (Figure 7B). In this symmetry-governed configuration of the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex, two-residue grooves continue into no-residue-containing 5´–3´ grooves, while single-residue grooves continue into single-residue grooves with similar T residues from the two monomers (Figure 7E, residues T4 and T4* are oriented in opposite directions). This alignment appears to be favored for positioning of the mass center, and likely reflects favorable solution hydrodynamic properties of the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex with looped out residues.

Comparison of Stacking Patterns Amongst Dimeric G-Quadruplexes

There have been several examples of end-on-end association to form dimeric G-quadruplexes that exhibit distinct characteristics from that observed in the current study on the 5´-end-stacked dimeric pilE G-quadruplex. The earliest examples involved dimeric G-quadruplex formation involving two-layered monomers that are mediated by 5´-end stacked A•(G•G•G•G)•A hexads (Figure S8A) (Kettani et al., 2000b), and heptads (Matsugami et al., 2003; Matsugami et al., 2001). Additional examples of 5´-end stacked G-tetrads involve formation of an interlocked 93del dimeric G-quadruplex targeted to HIV integrase, where the interfacial G-tetrads involve one G(syn) residue from one monomer aligned antiparallel to three G(anti) residues from the other monomer (Figure S8D) (Phan et al., 2005b), as well as an interlocked V-shaped dimeric G-quadruplex containing A•(G•G•G•G) pentads (Figure S8G) (Zhang et al., 2001).

The observed features of the overlap geometry of the interfacial G-tetrads in the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex include stacking between guanine six-membered rings, as well as between guanine amino groups and five-membered rings (Figure 7D). These overlap geometries are distinct from their counterparts in dimeric G-quadruplexes involving interfacial A•(G•G•G•G)•A hexads (Figures S8A, B), interlocked 93del (Figures S8D, E) and V-shaped (Figures S8G, H) topologies. For these three families of dimeric G-quadruplexes, the overlap pattern between junctional G-tetrads involves stacking between guanine five-membered rings and between guanine amino groups (Figures S8B, E and H).

In addition, sugar residues of the junctional G-tetrads do not stack over each other, but rather are twisted by one helical step, such that sugar of G1 projects vertically on the sugar of G6 rather than G5, in the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex (Figures 7D, E). By contrast, sugar residues of junctional G-tetrads either stack directly over each other as observed for the dimeric G-quadruplex involving interfacial A•(G•G•G•G)•A hexads (Figures S8B, C), or are twisted to a lesser extent in the interlocked 93del (Figures S8E, F) and V-shaped (Figures S8H, I) dimeric G-quadruplexes..

Comparison of Dimeric pilE and c-kit2 G-quadruplexes

For the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex elucidated in this work, two monomeric units associate through 5´-end stacking (Figure S9A). Recently, we have demonstrated that the G-rich sequence from intergenic region upstream of the c-kit oncogene promoter, termed c-kit2, forms a different and unique dimeric G-quadruplex in solution. In the ckit-2 dimeric G-quadruplex structure, two 5´-guanine tracts and two 3´-guanine tracts self-assemble in-register to form an all-parallel-stranded dimeric G-quadruplex scaffold (Figure S9B). Each of these two dimeric G-quadruplexes (Figures S9A, B) is composed of two three-layered subunits, but the pattern of their association exhibits distinct topologies. In the case of pilE G-quadruplex, two monomeric units self-associate through 5´-end stacking resulting in an anti-parallel orientation of outgoing DNA strands (Figure S9A), whereas in the ckit-2 G-quadruplex, the two three-layered monomeric units are covalently linked, and separated by a non-canonic A•A base pair, with a resulting parallel orientation of incoming and outgoing DNA strands (Figure S9B).

RecA is Targeted by the Monomeric pilE G-Quadruplex

The RecA family of ATPases catalyzes ATP-dependent strand exchange between single-stranded DNA and heterologous duplex DNA (Radding, 1981). The enzyme has two binding sites: a primary site, which binds single-stranded DNA and forms a RecA-ssDNA filament (pre-synaptic complex) and a secondary site, which binds a double stranded DNA target (site locations in Figure 9A). RecA binds ssDNA and dsDNA with differing affinities in these two sites (Mazin and Kowalczykowski, 1998). In the postsynaptic complex, the primary site is bound to double-stranded DNA, which is the product of recombination (Figure 9A) (Chen et al., 2008). Thus, although three strands are involved in strand exchange, RecA has enough space to simultaneously accommodate two DNA duplexes in the primary and secondary binding sites.

Two critical reaction residues in the secondary site, Arg235 and Lys237 (Kurumizaka et al., 1999) are separated from the primary site by a distance exceeding 24 Å, which is more than the diameter of a DNA double helix (Figure 9A) (Chen et al., 2008). Our fluorescence anisotropy measurements establish that RecA binds a monomeric three-layered all-parallel-stranded G-quadruplex containing single residue loops (Figure 9B), but not its counterpart containing three-residue loops (Figure S6B), nor does it bind to four-layered G-quadruplexes (Smith et al., 1995; Wang and Patel, 1995) (Figure S6C) or to the dimeric pilE G-quadruplex (Figure S6D). Our studies have identified a new higher order DNA substrate targeted to this important bacterial enzyme.

Potential Role for Monomeric pilE G-quadruplex in Recombination

The absolute requirement of RecA for pilin antigenic variation (Koomey et al., 1987) coupled with its reliance on the RecF-like recombination pathway (Mehr and Seifert, 1998), has implied that RecA could play a role in promoting strand exchange during recombination (Stohl et al., 2011). However, the finding that RecA binds the monomeric pilE G-quadruplex suggests that RecA may play additional roles in promoting pilin antigenic variation.

The G-quadruplex-forming pilE G4 DNA sequence is only present at one location in the gonococcal genome, upstream of pilE (Cahoon and Seifert, 2009). These data suggest that the monomeric pilE G-quadruplex could recruit RecA to the pilE locus to promote recombination between pilE and a pilS copy. Such a model should take into account the role of RecF-like pathway factors, RecQ, RecJ, RecO and RecR, that are all involved in pilin antigenic variation, and would have to act before or along with RecA (Mehr and Seifert, 1998; Sechman et al., 2005; Skaar et al., 2002).

We have outlined a proposed recombination mechanism based on a monomeric pilE G-quadruplex binding to RecA (Figure S10) in the Supplementary text. This proposed mechanism needs further validation, but has been put forward in the interest of stimulating further experiments.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protocols for sample preparation, NMR spectroscopy, gel electrophoresis, circular dichroism spectroscopy, fluorescence anisotropy, structure calculations, modeling of monomeric pile G-quadruplex into RecA, experiments outlining RecA-mediated strand exchange, and S1 nuclease digestion are presented in detail under Experimental Procedures in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by NIH Grant GM34504 to D.J.P. who is a member of the NY Structural Biology Center supported by NIH grant GM66354. This work was also supported by NIH grants RO1 AI044239 and R37 AI033493 to H.S.S. In addition, L.A.C. was partially supported by NIH grant T32GM08061.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Deposition: The coordinates of the NG22 monomeric (accession code: 2LXQ) and NG16 dimeric (accession code: 2LXV) G-quadruplexes have been deposited in the protein data bank.

Author Contributions: V.K. was responsible for the NMR-based structure determinations of the monomeric and dimeric pilE G-quadruplexes and proposed the recA binding hypothesis, under the supervision of D.J.P., while L.A.C. was responsible for the RecA-mediated binding and strand exchange experiments under the supervision of H.S.S.

Note Added in Proofs

While our manuscript was under revision, a paper was published on the J19 G-quadruplex, a potential inhibitor of HIV-integrase (Do et al., 2011). Similar to the dimeric pilE quadruplex reported in this study, the J19 G-quadruplex also forms a three-layered stacked dimeric G-quadruplex alignment (Figure S9C). Nevertheless, the two dimeric G-quadruplexes show distinct stacking patterns involving interfacial G-tetrads. In the pilE dimeric G-quadruplex reported in our study, the 5´-ends of the constitutive monomers are positioned on one side (Figure S9A), whereas the 5´-ends in J19 dimeric G-quadruplex are positioned diagonally on opposite sides (Figure S9C). The top projections reveal the importance of the mass center for selection of theoretically possible rotamers in these two dimeric G-quadruplex structures. The pilE dimeric G-quadruplex possesses four-fold pseudosymmetry so that the number of looped out residues stays equal to two on each axis (Figure S9D). By contrast, the J19 dimeric G-quadruplex contains all-single-residue loops and is characterized by an eightfold pseudosymmetry (Figure S9E), so that looped out elements (inclusive of single residues at 3´-ends) are distributed evenly along the perimeter of the dimeric scaffold.

REFERENCES

- Ambrus A, Chen D, Dai J, Jones RA, Yang D. Solution structure of the biologically relevant G-quadruplex element in the human c-MYC promoter. Implications for G-quadruplex stabilization. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2048–2058. doi: 10.1021/bi048242p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S, Hurley LH, Neidle S. Targeting G-quadruplexes in gene promoters: a novel anticancer strategy? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:261–275. doi: 10.1038/nrd3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge S, Parkinson GN, Hazel P, Todd AK, Neidle S. Quadruplex DNA: sequence, topology and structure. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:5402–5415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon LA, Seifert HS. An alternative DNA structure is necessary for pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Science. 2009;325:764–767. doi: 10.1126/science.1175653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate JH, Gooding AR, Podell E, Zhou K, Golden BL, Szewczak AA, Kundrot CE, Cech TR, Doudna JA. RNA tertiary structure mediation by adenosine platforms. Science. 1996;273:1696–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Yang H, Pavletich NP. Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature. 2008;453:489–484. doi: 10.1038/nature06971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criss AK, Kline KA, Seifert HS. The frequency and rate of pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Molecular microbiology. 2005;58:510–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JT. G-quartets 40 years later: from 5'-GMP to molecular biology and supramolecular chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:668–698. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedin A, Gros J, Alberti P, Mergny JL. How long is too long? Effects of loop size on G-quadruplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7858–7868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE. Mating-type gene switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annual review of genetics. 1998;32:561–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. Intragenic recombination leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature. 1985;315:156–158. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber MD, Lee DC, Maizels N. G4 DNA unwinding by BLM and Sgs1p: substrate specificity and substrate-specific inhibition. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:3954–3961. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettani A, Basu G, Gorin A, Majumdar A, Skripkin E, Patel DJ. A two-stranded template-based approach to G.(C-A) triad formation: designing novel structural elements into an existing DNA framework. J Mol Biol. 2000a;301:129–146. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettani A, Bouaziz S, Wang W, Jones RA, Patel DJ. Bombyx mori single repeat telomeric DNA sequence forms a G-quadruplex capped by base triads. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:382–389. doi: 10.1038/nsb0597-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettani A, Gorin A, Majumdar A, Hermann T, Skripkin E, Zhao H, Jones R, Patel DJ. A dimeric DNA interface stabilized by stacked A.(G.G.G.G).A hexads and coordinated monovalent cations. J Mol Biol. 2000b;297:627–644. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koomey M, Gotschlich EC, Robbins K, Bergstrom S, Swanson J. Effects of recA mutations on pilus antigenic variation and phase transitions in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Genetics. 1987;117:391–398. doi: 10.1093/genetics/117.3.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurumizaka H, Ikawa S, Sarai A, Shibata T. The mutant RecA proteins, RecAR243Q and RecAK245N, exhibit defective DNA binding in homologous pairing. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;365:83–91. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryavyi V, Kettani A, Wang W, Jones R, Patel DJ. A diamond-shaped zipper-like DNA architecture containing triads sandwiched between mismatches and tetrads. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:455–469. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryavyi V, Patel DJ. Solution structure of a unique G-quadruplex scaffold adopted by a guanosine-rich human intronic sequence. Structure. 2010;18:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryavyi V, Phan AT, Patel DJ. Solution structures of all parallel-stranded monomeric and dimeric G-quadruplex scaffolds of the human c-kit2 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6757–6773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryavyi VV, Jovin TM. Triad-DNA: a model for trinucleotide repeats. Nat Genet. 1995;9:339–341. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipps HJ, Rhodes D. G-quadruplex structures: in vivo evidence and function. Trends in cell biology. 2009;19:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Gilbert W. The yeast KEM1 gene encodes a nuclease specific for G4 tetraplex DNA: implication of in vivo functions for this novel DNA structure. Cell. 1994;77:1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maizels N. Dynamic roles for G4 DNA in the biology of eukaryotic cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1055–1059. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsugami A, Okuizumi T, Uesugi S, Katahira M. Intramolecular higher order packing of parallel quadruplexes comprising a G:G:G:G tetrad and a G(:A):G(:A):G(:A):G heptad of GGA triplet repeat DNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28147–28153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsugami A, Ouhashi K, Kanagawa M, Liu H, Kanagawa S, Uesugi S, Katahira M. An intramolecular quadruplex of (GGA)(4) triplet repeat DNA with a G:G:G:G tetrad and a G(:A):G(:A):G(:A):G heptad, and its dimeric interaction. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:255–269. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazin AV, Kowalczykowski SC. The function of the secondary DNA-binding site of RecA protein during DNA strand exchange. EMBO J. 1998;17:1161–1168. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehr IJ, Seifert HS. Differential roles of homologous recombination pathways in Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilin antigenic variation, DNA transformation and DNA repair. Molecular microbiology. 1998;30:697–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidle S. The structures of quadruplex nucleic acids and their drug complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeschke K, Simonsson T, Postberg J, Rhodes D, Lipps HJ. Telomere end-binding proteins control the formation of G-quadruplex DNA structures in vivo. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2005;12:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nsmb982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson GN, Lee MP, Neidle S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DJ, Kozlowski SA, Nordheim A, Rich A. Right-handed and left-handed DNA: studies of B- and Z-DNA by using proton nuclear Overhauser effect and P NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:1413–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.5.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DJ, Phan AT, Kuryavyi V. Human telomere, oncogenic promoter and 5'-UTR G-quadruplexes: diverse higher order DNA and RNA targets for cancer therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7429–7455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT. Long-range imino proton-13C J-couplings and the through-bond correlation of imino and non-exchangeable protons in unlabeled DNA. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;16:175–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1008355231085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Burge S, Neidle S, Patel DJ. Structure of an unprecedented G-quadruplex scaffold in the human c-kit promoter. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007a;129:4386–4392. doi: 10.1021/ja068739h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Gaw HY, Patel DJ. Small-molecule interaction with a five-guanine-tract G-quadruplex structure from the human MYC promoter. Nat Chem Biol. 2005a;1:234–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Luu KN, Patel DJ. Structure of two intramolecular G-quadruplexes formed by natural human telomere sequences in K+ solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007b;35:6517–6525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Ma JB, Faure A, Andreola ML, Patel DJ. An interlocked dimeric parallel-stranded DNA quadruplex: a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005b;102:634–639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406278102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Mody YS, Patel DJ. Propeller-type parallel-stranded G-quadruplexes in the human c-myc promoter. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:8710–8716. doi: 10.1021/ja048805k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Patel DJ. A site-specific low-enrichment (15)N,(13)C isotope-labeling approach to unambiguous NMR spectral assignments in nucleic acids. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:1160–1161. doi: 10.1021/ja011977m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Hurley LH. Structures, folding patterns, and functions of intramolecular DNA G-quadruplexes found in eukaryotic promoter regions. Biochimie. 2008;90:1149–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radding CM. Recombination activities of E. coli recA protein. Cell. 1981;25:3–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeyre C, Lopes J, Boule JB, Piazza A, Guedin A, Zakian VA, Mergny JL, Nicolas A. The yeast Pif1 helicase prevents genomic instability caused by G-quadruplex-forming CEB1 sequences in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudel T, van Putten JP, Gibbs CP, Haas R, Meyer TF. Interaction of two variable proteins (PilE and PilC) required for pilus-mediated adherence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to human epithelial cells. Molecular microbiology. 1992;6:3439–3450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechman EV, Rohrer MS, Seifert HS. A genetic screen identifies genes and sites involved in pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Molecular microbiology. 2005;57:468–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen D, Gilbert W. Formation of parallel four-stranded complexes by guanine-rich motifs in DNA and its implications for meiosis. Nature. 1988;334:364–366. doi: 10.1038/334364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissi C, Gatto B, Palumbo M. The evolving world of protein-G-quadruplex recognition: A medicinal chemist's perspective. Biochimie. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar EP, Lazio MP, Seifert HS. Roles of the recJ and recN genes in homologous recombination and DNA repair pathways of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:919–927. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.919-927.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FW, Schultze P, Feigon J. Solution structures of unimolecular quadruplexes formed by oligonucleotides containing Oxytricha telomere repeats. Structure. 1995;3:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Chen Q, Yatsunyk LA, Nicoludis JM, Garcia MS, Kranaster R, Balasubramanian S, Monchaud D, Teulade-Fichou MP, Abramowitz L, et al. Rudimentary G-quadruplex-based telomere capping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:478–485. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparling PF. Genetic transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to streptomycin resistance. Journal of bacteriology. 1966;92:1364–1371. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.5.1364-1371.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl EA, Blount L, Seifert HS. Differential cross-complementation patterns of Escherichia coli and Neisseria gonorrhoeae RecA proteins. Microbiology. 2002;148:1821–1831. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl EA, Gruenig MC, Cox MM, Seifert HS. Purification and characterization of the RecA protein from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the Tetrahymena telomeric repeat d(T2G4)4 G-tetraplex. Structure. 1994;2:1141–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the Oxytricha telomeric repeat d[G4(T4G4)3] G-tetraplex. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:76–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang M, Lauer P, Park HS, Brossay L, Hebert J, Koomey M. PilT mutations lead to simultaneous defects in competence for natural transformation and twitching motility in piliated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Molecular microbiology. 1998;29:321–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Shin-ya K, Brosh RM., Jr FANCJ helicase defective in Fanconia anemia and breast cancer unwinds G-quadruplex DNA to defend genomic stability. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:4116–4128. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02210-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Gorin A, Majumdar A, Kettani A, Chernichenko N, Skripkin E, Patel DJ. V-shaped scaffold: a new architectural motif identified in an A × (G × G × G × G) pentad-containing dimeric DNA quadruplex involving stacked G(anti) × G(anti) × G(anti) × G(syn) tetrads. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:1063–1079. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gostissa M, Hildebrand DG, Becker MS, Boboila C, Chiarle R, Lewis S, Alt FW. The role of mechanistic factors in promoting chromosomal translocations found in lymphoid and other cancers. Adv Immunol. 2010;106:93–133. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)06004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.