Abstract

Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells (iPSC-MSCs) are a promising choice of patient-specific stem cells with superior capability of cell expansion. There has been no report on bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2) gene modification of iPSC-MSCs for bone tissue engineering. The objectives of this study were to: (1) genetically modify iPSC-MSCs for BMP2 delivery; and (2) to seed BMP2 gene-modified iPSC-MSCs on calcium phosphate cement (CPC) immobilized with RGD for bone tissue engineering. iPSC-MSCs were infected with green fluorescence protein (GFP-iPSC-MSCs), or BMP2 lentivirus (BMP2-iPSC-MSCs). High levels of GFP expression were detected and more than 68% of GFP-iPSC-MSCs were GFP positive. BMP2-iPSC-MSCs expressed higher BMP2 levels than iPSC-MSCs in quantitative RT-PCR and ELISA assays (p < 0.05). BMP2-iPSC-MSCs did not compromise growth kinetics and cell cycle stages compared to iPSC-MSCs. After 14 d in osteogenic medium, ALP activity of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 1.8 times that of iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05), indicating that BMP2 gene transduction of iPSC-MSCs enhanced osteogenic differentiation. BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were seeded on CPC scaffold biofunctionalized with RGD (RGD-CPC). BMP2-iPSC-MSCs attached well on RGD-CPC. At 14 d, COL1A1 expression of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 1.9 times that of iPSC-MSCs. OC expression of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 2.3 times that of iPSC-MSCs. Bone matrix mineralization by BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was was 1.8 times that of iPSC-MSCs at 21 d. In conclusion, iPSC-MSCs seeded on CPC were suitable for bone tissue engineering. BMP2 gene-modified iPSC-MSCs on RGD-CPC underwent osteogenic differentiation, and the overexpression of BMP2 in iPSC-MSCs enhanced differentiation and bone mineral production on RGD-CPC. BMP2-iPSC-MSC seeding on RGD-CPC scaffold is promising to enhance bone regeneration efficacy.

Keywords: bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), bone tissue engineering, calcium phosphate cement (CPC), gene transduction, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), RGD immobilization

1. Introduction

Bone defects occur frequently as a result of trauma, tumor ablative surgery, congenital defects, infectious conditions and other causes of loss of skeletal tissue [1,2]. The supply of bone grafts to treat critical-sized bone defects remains a major challenging health issue worldwide [3]. Failure of bone defect repair often leads to severe functional and esthetic deformities. Bone tissue engineering methods using stem cells and scaffolds provide new promising approaches for bone repair [4–11]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are progenitor cells for bone regeneration, and bone marrow derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) were extensively investigated [2,12]. However, because of the invasive harvest procedure of BM-MSCs and their decreased potency in senior patients with diseases, alternative sources of MSCs have been investigated including adipose tissue, deciduous tooth, umbilical cord and many other tissues [13].

Recently, a groundbreaking approach by Yamanaka and colleagues generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from adult somatic cells using reprogramming techniques, yielding cell proliferation and differentiation potential similar to embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [14–16]. iPSCs provide a promising method for obtaining patient-specific stem cells for tissue regeneration. However, iPSCs have the potential to be expanded indefinitely and may result in tumor formation after transplantation [16]. Therefore, Lian et al. further derived MSCs from human iPSCs, which were referred to as iPSC-MSCs [17]. The biosafety of iPSC-MSCs was improved when compared with the direct use of iPSCs [16]. iPSC-MSCs have superior potential for cell expansion, which is critically important because large numbers of expanded stem cells are needed for cell transplantation and regenerative medicine therapy [18]. Despite of these advantages, only a few investigations have investigated iPSC-MSCs for bone regeneration [19].

Local and sustained delivery of osteoinductive growth factors is an effective approach to promote bone regeneration. Gene therapy strategy has been used for this purpose because it has advantages over direct growth factor delivery, such as low cost and sustained long-term release [20]. Bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2), a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily, has a remarkable capability of inducing bone formation [21–23]. Preclinical and clinical investigations have successfully applied BMP2 in the therapy of bone defects [24]. Various vectors have been tested to deliver BMP2 by gene therapy, such as liposome-mediated plasmid DNA delivery, adenoviral vectors, and lentiviral vectors [21–23]. Lentiviral vectors with minimal immunogenicity and improved biosafety after a series of modifications could transduce BM-MSCs with high efficiency and long-term stability, which were used to repair bone defect with superior mechanical quality [22,25,26]. However, to date there has been no report on BMP2 gene modification of iPSC-MSCs for bone tissue engineering.

Among various scaffolds for bone regeneration, calcium phosphate (CaP) scaffolds are important for bone repair because they are bioactive, mimic bone minerals and can bond to neighboring bone [27–31]. Calcium phosphate cements (CPCs) can set in situ at the body temperature and conform to complex-shaped bone defects [32–36]. CPC used tetracalcium phosphate and dicalcium phosphate anhydrous, and was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of USA in 1996 [32,37–39]. CPC exhibited excellent osteoconductive properties and was resorbed and replaced by new bone in vivo [37–40]. Attempts were made to improve the mechanical properties of CPC, for example, by incorporation of chitosan [41]. To enhance the biocompatibility of CPC, immobilization of Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) on chitosan was recently performed before mixing the chitosan with CPC. This yielded RGD-CPC which significantly improved cell attachment when compared to traditional CPC [41]. However, to date there has been no report on human iPSC-MSC seeding on RGD-CPC scaffold.

The objectives of this study were to genetically modify human iPSC-MSCs for BMP2 delivery, and to seed BMP2 gene-modified iPSC-MSCs on chitosan-CPC scaffold immobilized with RGD for bone tissue engineering. The following hypotheses were tested: (1) BMP2 delivery by gene therapy will promote osteogenic differentiation of iPSC-MSCs while having no significant adverse effect on cell growth; (2) BMP2 gene-modified iPSC-MSCs will attach to chitosan-CPC scaffold with RGD immobilization, survive well and result in enhanced osteogenic differentiation and bone mineral production.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. iPSC culture

The culture of human iPSCs was approved by the University of Maryland Baltimore Institutional Review Board (HP-00046649). Human iPSC BC1 line was derived from adult bone marrow CD34+ cells as described recently, and the cells were kindly provided by Dr. Linzhao Cheng of the Johns Hopkins University [43,44]. Human primary mononuclear cells (MNCs) from a healthy adult marrow donor (code: BM2426) were isolated using a standard gradient protocol by Ficoll-Paque Plus (p = 1.077). CD34+ cells were then purified using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) system and cultured with hematopoietic cytokines for 4 days (d) before being reprogrammed by a single episomal vector pEB-C5 [43,44]. iPSCs were expanded on a feeder layer of mitotically-inactivated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) as ESCs [41]. Mitotically-inactivated MEFs as feeder cells were mixed with iPSCs. The iPSC colonies were dissociated into clumps through treatment with 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV for 6 min, followed by mechanical scraping while avoiding the detachment of the MEF layer from the plate surface. Then, the iPSCs were induced to form embryoid bodies (EBs) in suspension culture with ultra-low-attachment plates (Corning, Corning, NY) for 10 d [41]. If residual inactivated MEFs were present, they would attach to the bottom of the flask in the first few days. Once the attached inactivated MEFs were observed, the floating EBs were transferred to a new flask, thereby avoiding the adherent MEFs [42]. In this way, after suspension culture for 10 d, any residual inactivated MEFs had been removed from the EBs. The EB formation medium was composed of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (serum-free; Life Technologies), 1% MEM non-essential amino acids solution (Life Technologies), 1 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and changed every 2 d. The EBs were transferred and cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated plates for 10 more d. The iPSC-MSCs migrated out from the EBs and were then isolated by cell scrapers. iPSC-MSCs were expanded using growth medium composed of low glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies), 10% hMSC screened fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine (Life Technologies). A preliminary investigation characterized the expression of surface markers of iPSC-MSCs using flow cytometry. More than 90% of the cells expressed MSC surface markers CD29, CD44, CD166, CD73. iPSC-MSCs were positive for characteristic MSC markers CD105 and HLA-class I (HLA-ABC). The endothelial marker (CD31), hematopoietic linage marker (CD34), or the iPSC pluripotency markers (TRA-1–81 and Oct3/4) were negative. The preliminary study concluded that iPSC-MSCs expressed surface markers characteristic of MSCs, and were negative for typical hematopoietic and endothelial cell markers. Passage 3 iPSC-MSCs were subjected for lentiviral gene transduction in the present study.

2.2 Lentivirus production and gene transduction

Lentivirus, expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) or human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), was produced commercially (GenTarget Inc., San Diego, CA), as previously described [22,45]. Briefly, GFP or BMP2 gene sequence was sub-cloned into a third generation of human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1)-based expression lentivector under the transcriptional control of EF-1α promoter. The third generation lentiviral vector system with 3'-LTR self-inactivation mechanism only generates replication-incompetent lentivirus. The inserted sequence was verified by sequencing analysis. Expression lentiviral particles were produced in 293T cells by co-transfection with both the lentivectors and lentiviral packaging plasmids (GenTarget). Virus titers were measured in TH1080 cells via HIV-1 p24 ELISA assay (Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Rockville, MD).

iPSC-MSCs at passage 3 were seeded on a CytoOne 24-well tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) plate (USA Scientific, Ocala, FL). Upon 50% confluence, iPSC-MSCs were infected with the GFP or BMP2 lentivirus with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 15 for 3 d according to the manufacturer’s instructions, which were referred to as GFP-iPSC-MSCs or BMP2-iPSC-MSCs, respectively. The MOI of 15 was adopted because a high expression of GFP (more than 68% positive) was observed when iPSC-MSCs were infected with GFP lentivirus using this MOI in preliminary experiment. Then GFP-iPSC-MSCs or BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were expanded in growth medium. Up to passage 8 of gene-modified iPSC-MSCs were examined to determine the stability of target gene transduction. Passage 6 cells were seeded on CPC scaffold.

GFP-iPSC-MSCs were used to evaluate the transduction efficiency and stability. Passage 5 to 8 GFP-iPSC-MSCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (USB, Cleveland, OH) for 10 min at room temperature and then washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS; Life Technologies). Cells were stained with 4’,6-Diamidine-2’-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Roche, Germany; 2 μg/mL) in D-PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min, washed with D-PBS, and immediately subjected for fluorescent assay using epifluorescence microscopy (Eclipse TE2000-S; Nikon, Melville, NY). The transduction efficiency was analyzed by a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) to count the number of GFP-positive cells, using untransducted iPSC-MSCs as negative control.

2.3 BMP2 gene expression and protein secretion

To detect the success and stability of BMP2 gene transduction, passage 5 to 8 BMP2-iPSC-MSCs cultured on 24-well TCPS were harvested. BMP2 gene expression was analyzed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR, 7900HT, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the 2−ΔΔCt method [46]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent and the PureLink RNA Mini Kit and reverse-transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). PCR was carried out using TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix with No AmpErase UNG (Life Technologies). The PCR-primers and TaqMan probes (Taqman Gene Expression Assay Mix, Life Technologies) included human BMP2 (Hs00154192_m1) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Hs99999905_m1; reference gene).

The BMP2 protein secretion from iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (passage 5 to 8) was evaluated by measuring BMP2 amount in the conditioned medium, as described previously [23]. Briefly, cells were cultured on 75 cm2 TCPS flasks and the cell supernatants were collected during a 24-hour culture. The cell number was determined using a hemocytometer counting chamber (Lumicyte, Propper Manufacturing Company, Long Island, NY). The supernatants were centrifuged at 3000 rcf and 4 °C for 10 min to remove cellular debris and particulate and stored in aliquots at −80 °C. BMP2 concentration was measured using a human BMP2 Immunoassay kit (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The secreted BMP2 amount was reported as ng/day/million cells [23].

2.4 Growth kinetics and cell cycle analysis

The growth kinetics of three consecutive passages (passage 4 to 6) of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was evaluated by calculation of average population doubling time (PDT), as described previously [47]. Briefly, cells were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells per cm2 on 24-well TCPS. The number of cells was determined for 5 consecutive days and the values in the exponential growth phase were used. PDT was calculated using the formula PDT = t/log2(Nf / Ni), where t = culture time in hours, Nf = final cell number, and Ni = initial cell number.

iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (passage 5 and 6) were subjected for cell cycle analysis. Two million iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were collected by trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies) treatment and centrifugation at 180 rcf for 5 min, washed with D-PBS twice, and fixed in cold 70% ethanol at 4 °C overnight. Cells were washed and incubated with 1 mg/mL RNase A (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in D-PBS at 37 °C for 30 min. After that, cells were incubated in the dark in a solution containing 100 µg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.9% NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 30 min and then subjected to cell-cycle analysis using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

2.5 Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity staining and quantification

The activity of ALP, a crucial component for initiating mineralization, was detected to evaluate the effect of BMP2 gene transduction on iPSC-MSC osteogenesis [48]. The preliminary study demonstrated that weak ALP activity was detected when BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were cultured on TCPS in growth medium for up to 14 d. Therefore, for osteogenic induction, iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (passage 6) were cultured on 24-well TCPS plates in osteogenic medium consisted of the growth medium plus 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.05 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). After 7 and 14 d incubation, ALP activity was determined by both staining and colorimetric quantification. For ALP staining, cells were fixed for 30 seconds using citrate-acetone-formaldehyde fixative. Staining was performed using a leukocyte alkaline phosphatase kit (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The ALP-positive cells were stained blue.

For quantification of ALP activity, cells were lysed using 250 µL of M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Fisher), centrifuged at 12,000 rcf and 4 °C for 10 min, and then stored in aliquots at −80 °C. ALP activity was determined colorimetrically using a LabAssay ALP kit (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) with p-Nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) as a substrate. The amount of DNA in the same cell lysate was measured using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Life Technologies). ALP activity was normalized to the DNA amount and reported as mM pNPP/min/µg DNA.

2.6 Scaffold fabrication

Tetracalcium phosphate (TTCP; Ca4(PO4)2O) was produced using equimolar amounts of anhydrous dicalcium phosphate (DCPA; CaHPO4) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) (J.T. Baker, Philipsburg, NJ), as described previously [49]. The CPC powder was prepared by mixing TTCP and DCPA at a 1: 1 mole ratio. Water-soluble chitosan (chitosan lactate; Halosource Inc., Redmond, WA) was covalently conjugated with a G4RGDSP oligopeptide (Peptides International, Louisville, KY) as described previously [41,46,50]. The reaction product, RGD-immobilized chitosan, was incorporated into the CPC scaffold (referred to as RGD-CPC) [41]. Briefly, chitosan was dissolved in 0.1M MES buffer to produce a 1% solution (pH 6.5, containing 0.5 M NaCl). 1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC; Thermo Fisher), sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS; Thermo Fisher), and G4RGDSP peptide were added to the chitosan solution (molar ratio of G4RGDSP / EDC / NHS = 1 / 1.2 / 0.6). The weight ratio of chitosan / G4RGDSP / EDC / NHS was 1000 / 12.4 / 3.8 / 2.1). After 24 h, the reaction was quenched by adding hydroxylamine. The solution was dialyzed with distilled water for 4 d and then lyophilized.

To fabricate CPC disk, the RGD-chitosan solution was used as the CPC liquid and a powder to liquid mass ratio of 2:1 was used [41]. RGD-chitosan was dissolved in distilled water with a mass fraction of 8% at 37 °C. The mixed paste was filled into a disk mold with a diameter of 12 mm and a thickness of 1.5 mm and incubated at 37°C in a humidor for 24 h. The RGD-CPC disks were sterilized in an ethylene oxide sterilizer (Anprolene AN 74i, Andersen, Haw River, NC) for 12 h and then degassed for 7 d.

2.7 Cell attachment and viability on RGD-chitosan-CPC

A live/dead assay (Life Technologies) was used to compare the viability of iPSC-MSCs with BMP2-iPSC-MSCs seeded on RGD-chitosan-CPC disks [46]. Each disk was placed in a well of a 24-well plate and immersed in DMEM medium for 1 day before cell seeding. Then 1.5×105 cells in growth medium was added to each well. The medium was changed three times a week. After 1, 4, and 7 d, the disks were washed with D-PBS and stained with 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1) and 2 μM calcein-AM in D-PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Disks were examined using epifluorescence microscopy (Eclipse TE2000-S, Nikon, Melville, NY). Five randomly-chosen images for each sample were analyzed for four disks, yielding 20 images per group. The live (green) and dead (red) cells were counted. The percentage of live cells and the live cell density were calculated [51].

2.8 Osteogenic differentiation assay of cells on RGD-CPC

iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were suspended in osteogenic medium and seeded on RGD-CPC disks which were placed in 24-well plates (each well with one disk and 1.5×105 cells). The osteogenic medium was changed three times a week and the disks were collected at 1, 7, and 14 d. qRT-PCR assay was performed to compare the osteogenic differentiation of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs. The method of qRT-PCR assay was described in section 2.3. The information of PCR-primers and TaqMan probes (Taqman Gene Expression Assay Mix, Life Technologies) for the osteogenic genes detected in the present study was as follows: collagen type 1 alpha 1 (COL1A1, Hs00164004_m1), osteocalcin (OC, Hs00609452_g1), and GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1; reference gene). iPSC-MSCs (passage 6) cultured on TCPS in the growth medium for 1 d served as the calibrator [52].

2.9 Cell mineralization on RGD-chitosan-CPC

Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used to determine the mineralization of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs. After 7, 14 and 21 d in osteogenic medium, the constructs were collected, fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with ARS at room temperature for 30 min. The time points were chosen because a large accumulation of calcium content happened from 14 d to 21 d during osteogenesis of MSCs in vitro in a previous study [53]. The constructs were washed with deionized water for five times and the calcium-rich minerals were stained red. Using an osteogenesis assay kit (Millipore), the stained deposits were extracted according to the manufacture’s instructions. ARS concentration was measured on a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 405 nm, using ARS standards to create a standard curve. RGD-CPC disks with no cell seeding were also examined, and their mean value was subtracted for each sample with cells, to yield the net mineralization value by the cells [54].

To evaluate the significant effects of the variables, one-way and two-way ANOVA were performed, and Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were adopted with a p value of 0.05.

3. Results

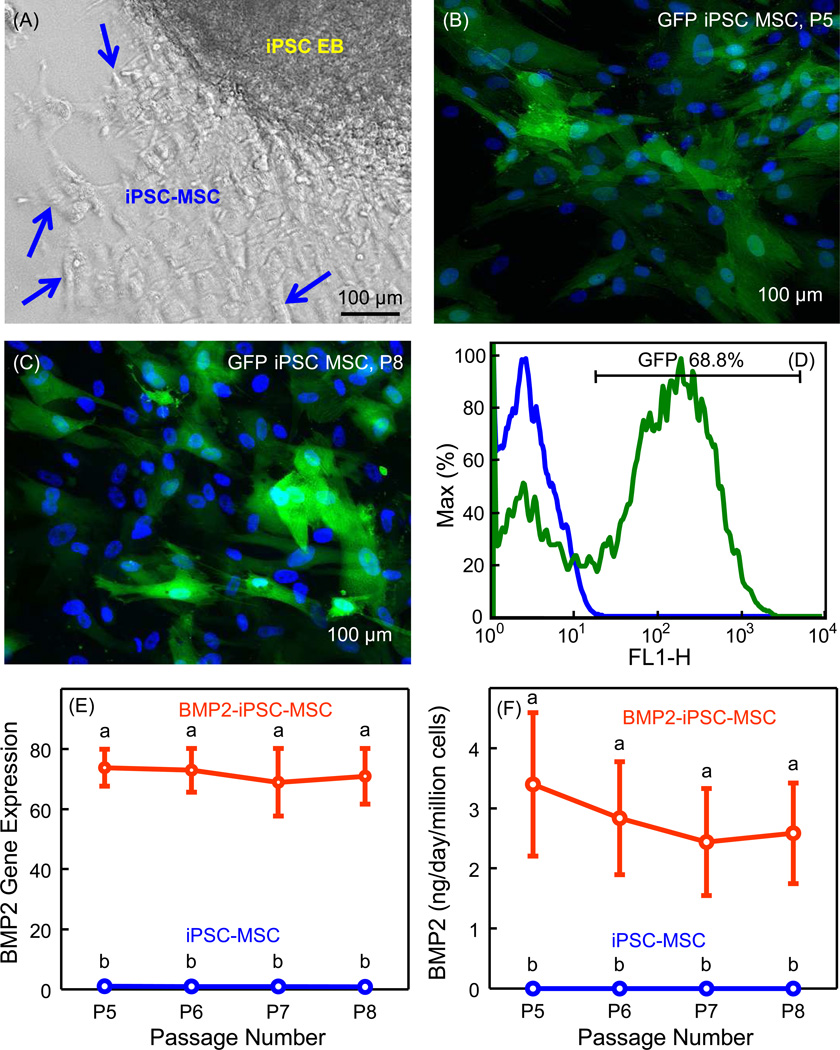

When deriving MSCs from iPSC EBs, cells with a fibroblast-like morphology were observed to migrate out of the EBs, which were the iPSC-MSCs (Fig. 1A). The homogeneity of cell morphology improved with higher passage numbers. The derived cells became relatively uniform in size and shape after passage 3. To examine lentiviral transduction efficiency and stability, GFP-iPSC-MSCs were examined using epifluorescence microscopy. No green fluorescence was detected in iPSC-MSCs. In contrast, high level of GFP expression was constantly detected in passage 5 to 8 GFP-iPSC-MSCs (Fig. 1B and 1C). The flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that more than 68% of GFP-iPSC-MSCs were GFP positive cells. Fig. 1D shows a representative graph of the flow cytometry analysis. Thus, the lentivector under the transcriptional control of EF-1α promoter was successfully selected for gene transduction of iPSC-MSCs with stability and high efficiency.

Fig. 1.

Derivation of iPSC-MSCs and lentiviral transduction. (A) MSCs migrated out of the iPSC embryoid bodies (EBs). Arrows indicate the iPSC-MSCs, which were later harvested and expanded for the experiments. (B and C) GFP-iPSC-MSCs were examined using epifluorescence microscopy. GFP was green and cellular nuclei were blue. Green fluorescence was constantly detected in passage 5 to 8 GFP-iPSC-MSCs. (D) Flow cytometry of GFP lentivirual-transducted iPSC-MSCs compared with untransducted iPSC-MSCs. The graph is a representative of 4 independent experiments in duplicate (iPSC-MSCs, blue line; GFP-iPSC-MSCs, green line). (E) BMP2 gene expressions in iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs from passage 5 to 8 (mean ± sd; n = 5). BMP2-iPSC-MSCs expressed higher BMP2 than iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). (F) ELISA assay of BMP2 production of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs from passage 5 to 8 (mean ± sd; n = 5). BMP2-iPSC-MSCs released more BMP2 than iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). In (E) and (F), values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

In Fig. 1E, BMP2-iPSC-MSCs from passage 5 to 8 stably expressed higher BMP2 gene levels than iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). BMP2 gene expression of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was approximately 70 times that of iPSC-MSCs. In Fig. 1F, higher BMP2 protein levels were determined in BMP2-iPSC-MSCs than that in iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). At passage 5 to 8, a million BMP2-iPSC-MSCs secreted approximately 3 ng of human BMP2 per day. These results demonstrated that the lentiviral-mediated BMP2 gene transduction of iPSC-MSCs was successful and stable.

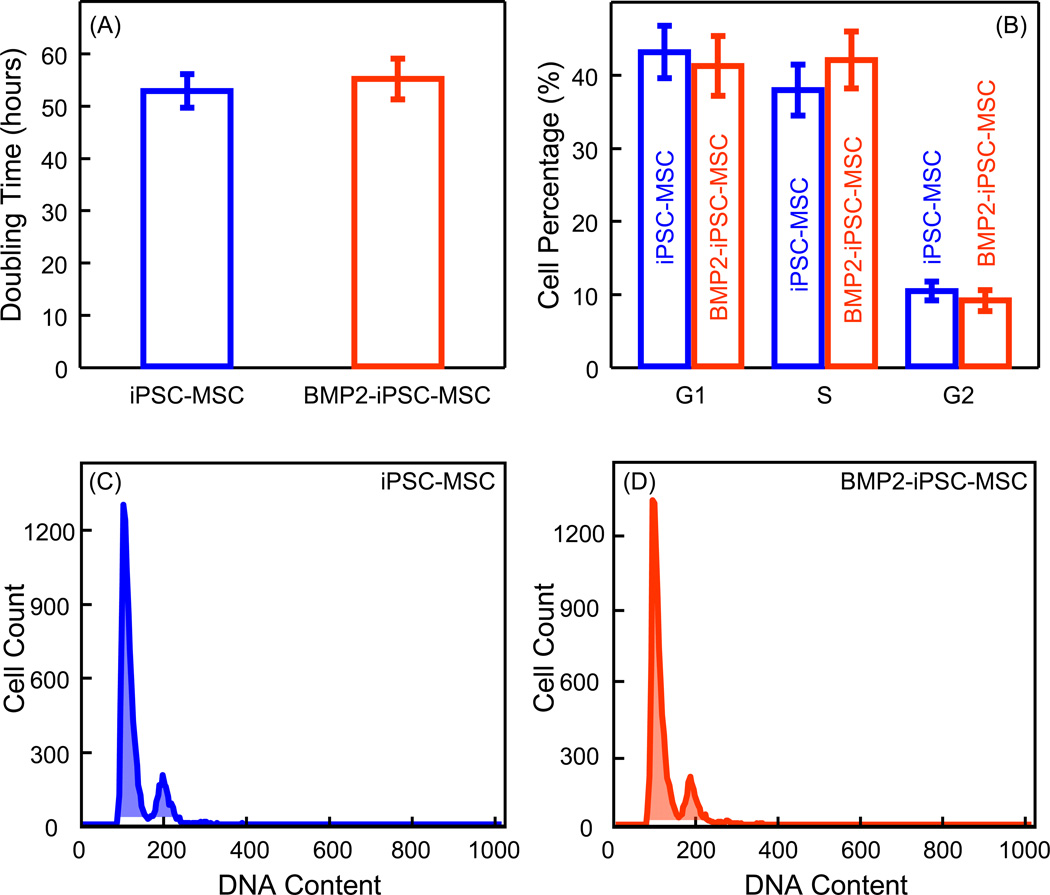

To determine whether the BMP2 gene transduction of iPSC-MSCs influenced cell growth, the growth kinetics and cell cycle stages were analyzed. There was no significant difference of PDT between iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, there was no significant difference of percentages of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs in G1, S, and G2 phages (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2B). Fig. 2C and 2D show representative graphs of cell cycle analysis of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs, respectively. These results showed that there was no difference in growth kinetics and cell cycle stages between iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs.

Fig. 2.

Growth kinetics and cell cycle analysis. (A) The average population doubling times (PDT) (mean ± sd; n = 5). There was no significant difference between iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (p > 0.05). (B) Cell cycle analysis (mean ± sd; n = 4). There was no significant difference of percentages of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs in G1, S, and G2 phages (p > 0.05). (C and D) Representative graphs of cell cycle analysis of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs using a flow cytometer. There was no statistical difference in growth kinetics and cell cycle stages between iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs.

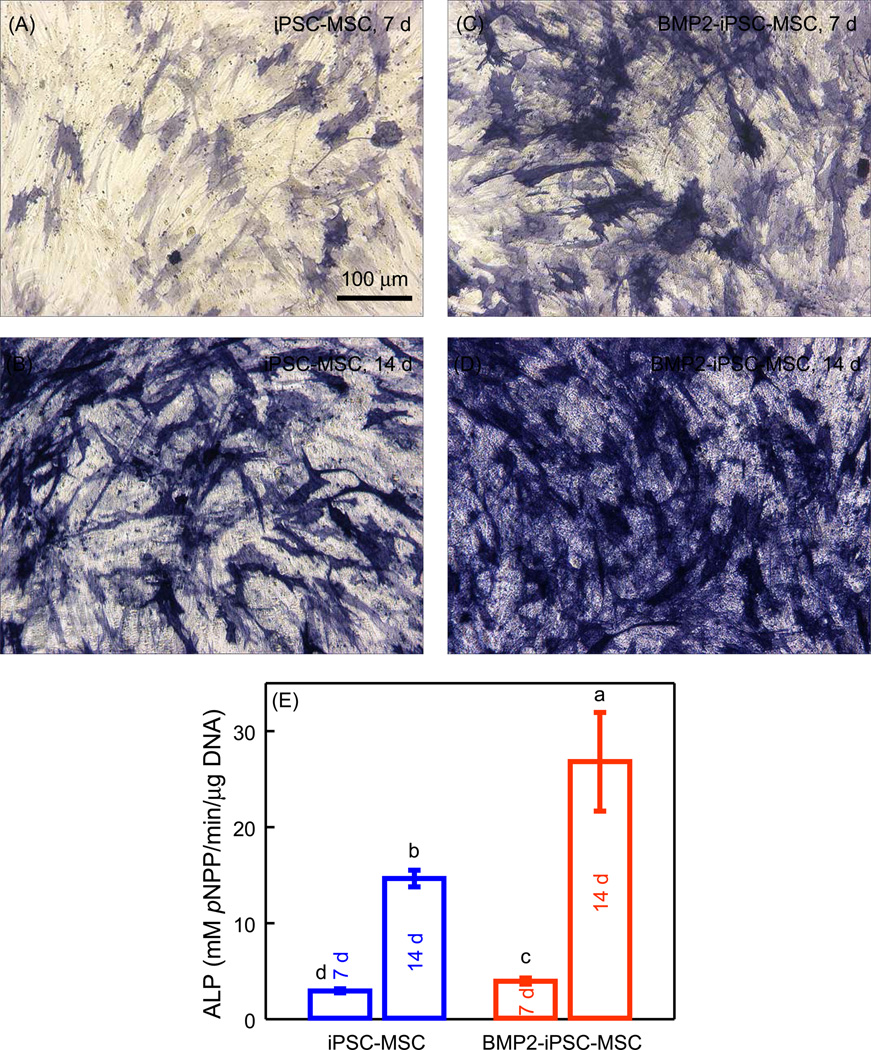

The ALP staining of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was more intense compared with iPSC-MSCs at 7 d and 14 d (Fig. 3A–D). The quantitative ALP activity of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was higher than iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3E). ALP activity of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 1.8 times that of iPSC-MSCs at 14 d. These results showed that BMP2 gene transduction of iPSC-MSCs led to enhanced osteogenic differentiation.

Fig. 3.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. ALP staining of (A and B) iPSC-MSCs and (C and D) BMP2-iPSC-MSCs cultured in osteogenic medium on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) at 7 and 14 d. (E) Quantification of ALP activity (mean ± sd; n = 4). The ALP activity was significantly higher in BMP2-iPSC-MSCs, compared with iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). In (E), values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

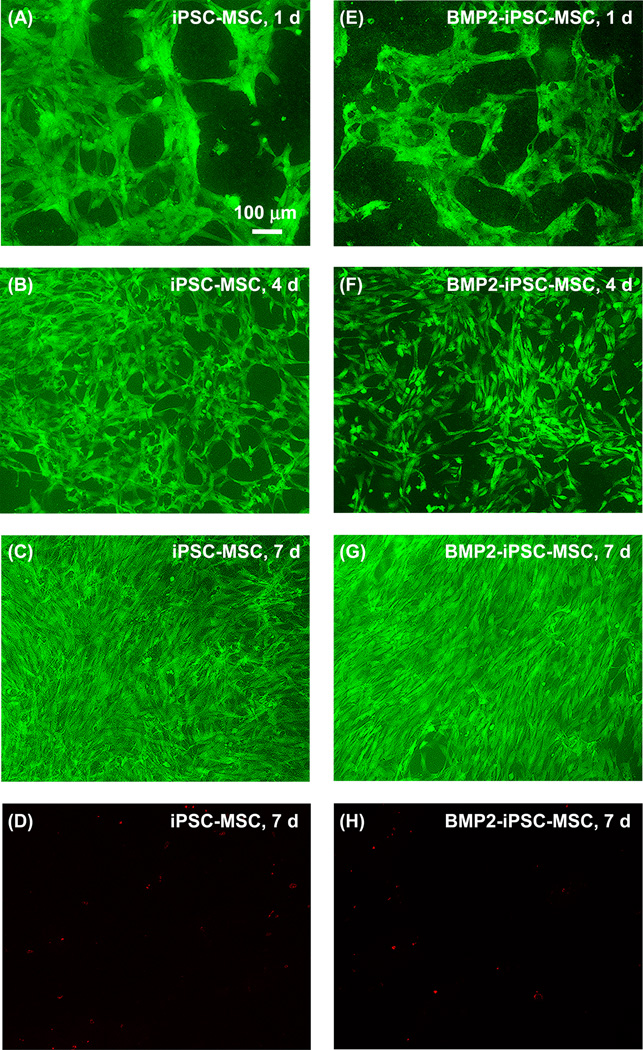

Live and dead assay was used to determine cell attachment and viability on RGD-CPC (Fig. 4). Most iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were alive and gradually reached confluence on from 1 to 7 d. Few cells were dead and the example at 7 d was shown in Fig. 4D and 4H.

Fig. 4.

Live and dead assay of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs on RGD-CPC. Live cells were shown green and dead cells were stained red. Most iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were alive and gradually reached confluence at 7 d. Only few cells were dead. Examples at 7 d are shown in (D) and (H).

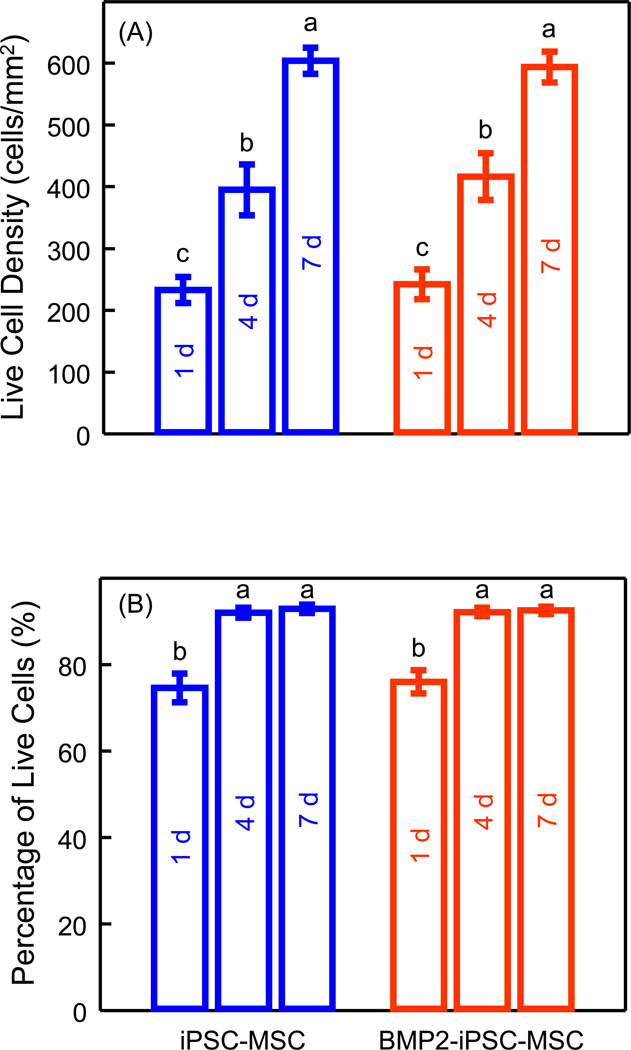

The live cell density and percentages of live cells were quantified (Fig. 5). The density of live iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs increased with culture time. There was no significant difference between iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (p > 0.05). At 7 d, both the percentages of live iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were approximately 93%. Therefore, BMP2-iPSC-MSCs attached and survived on RGD-CPC as well as iPSC-MSCs.

Fig. 5.

Quantification of live cell density (A), and percentages of live cells (B). Each value is mean ± sd; n = 5. There was no significant difference in both live cell density and percentages of live cells between iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs (p > 0.05). In both plots, values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

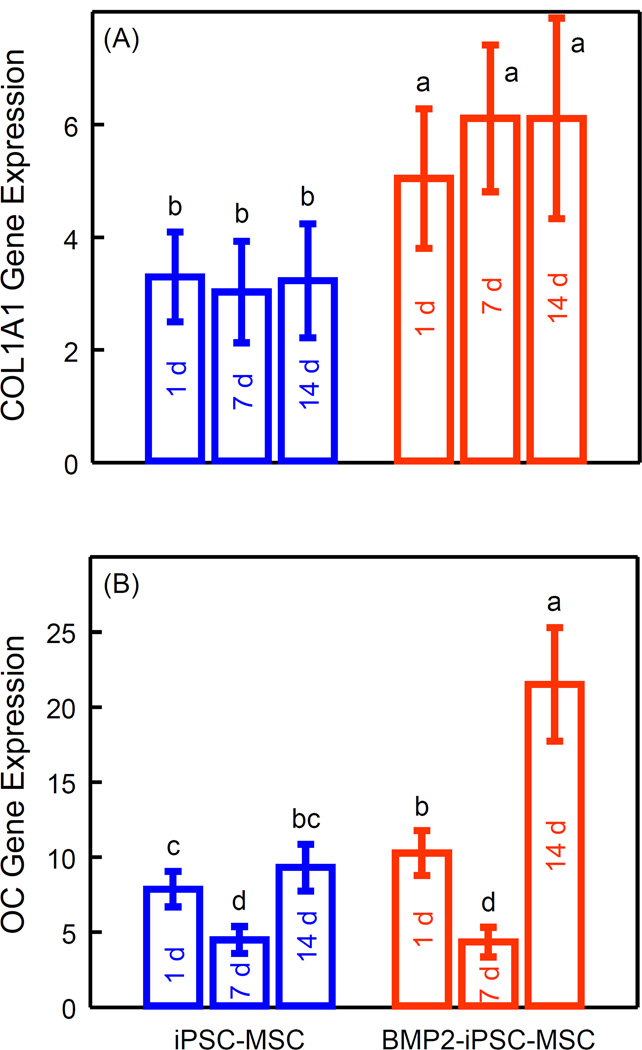

Osteogenic differentiation of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 6). COL1A1 and OC expression were up-regulated in both groups (p < 0.05). Hence, both iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs differentiated into the osteogenic lineage. Moreover, COL1A1 expression of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was higher than that of iPSC-MSCs at 1 d, 7 d and 14 d (p < 0.05). At 14 d, COL1A1 expression of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 1.9 times that of iPSC-MSCs. At 14 d, OC expression of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 2.3 times that of iPSC-MSCs. These results indicate that osteogenic differentiation of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs on RGD-CPC was enhanced, compared to that of iPSC-MSCs.

Fig. 6.

Gene expression assay of osteogenic differentiation of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs on RGD-CPC. The constructs were cultured in osteogenic medium. Data were demonstrated as mean ± sd (n = 5). Both (A) collagen type 1 alpha 1 (COL1A1) and (B) osteocalcin (OC) expression were up-regulated in both groups (p < 0.05), indicating that iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs differentiated into the osteogenic lineage. Moreover, COL1A1 expression was significantly higher in BMP2-iPSC-MSCs at 1 d, 7 d, and 14 d, compared with iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). OC expression was significantly higher in BMP2-iPSC-MSCs at 1 d and 14 d, compared with iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). In both plots, values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

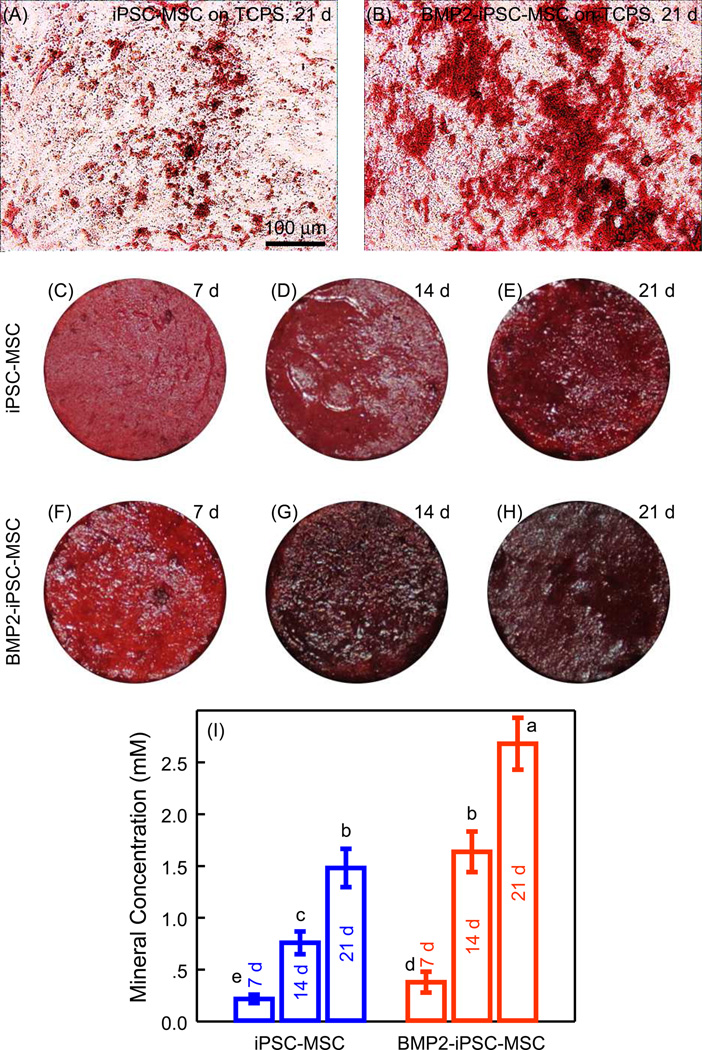

First, iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were seeded on TCPS and cultured in ostegenic medium to examine mineralization. At 21 d, ARS staining of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was more pronounced than iPSC-MSCs (Fig. 7A and 7B). Then, iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs were cultured on RGD-CPC (Fig. 7C–7H). Mineralization of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was denser and appeared to be thicker than iPSC-MSCs. Quantification in Fig. 7I showed that BMP2-iPSC-MSCs produced more mineralization than iPSC-MSCs (p < 0.05). At 21 d, the mineralization concentration of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was 1.8 times that of iPSC-MSCs.

Fig. 7.

Mineralization of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs. Cells were cultured in osteogenic medium for up to 21 d, and stained red using Alizarin Red S (ARS). (A and B) Representative images of ARS staining of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs cultured on TCPS at 21 d. More bone minerals were synthesized by BMP2-iPSC-MSCs, compared with iPSC-MSCs. (C–H) ARS staining of iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs cultured on RGD-CPC. For both iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs, the mineralization staining became thicker and darker from 7 d to 21 d. Mineralization of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs was denser and thicker than that of iPSC-MSCs. (I) Quantification of mineralization produced by iPSC-MSCs and BMP2-iPSC-MSCs on RGD-CPC (mean ± sd; n = 5). Values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Previous investigations genetically modified BM-MSCs or MSCs derived from adipose tissue (AT-MSCs) for overexpressing BMP2 [21–23,25]. BMP2 gene modified BM-MSCs or AT-MSCs were used for bone regeneration with high efficiency compared with BM-MSCs or AT-MSCs without gene modification [21–23,25]. For the first time, the present study demonstrated that BMP2 gene transduction of human iPSC-MSCs enhanced osteogenic differentiation and produced more mineral. Meanwhile, BMP2 delivery by gene therapy had no adverse effect on iPSC-MSC growth and attachment to CPC scaffold. Therefore, BMP2 gene modified iPSC-MSCs were promising progenitor cells for bone tissue engineering.

Despite of their outstanding advantages such as donor specificity and high expansion potential, only a few studies examined iPSC-MSCs for tissue engineering [17–19]. iPSC-MSCs were used to treat severe hind-limb ischemia and promote vascular and muscle regeneration, which were superior to BM-MSCs [17]. In addition, iPSC-MSCs exhibited strong self-renewal potential and were promising for autologous cardiac repair with low cost and high efficiency [18]. In another study, the potential of iPSC-MSCs to regenerate bone was evaluated by transplanting iPSC-MSCs into calvaria defects in immunocompromised mice [19]. De novo bone formed in the calvaria defects, and the transplanted human iPSC-MSCs were confirmed to have participated in bone regeneration. A major concern for clinical application of iPSC-MSCs was their safety because they were derived from pluripotent iPSCs which might lead to tumorigenesis [16]. Our preliminary investigation using the same method to derive MSCs form iPSCs showed that TRA-1–81 or Oct3/4 (the iPSC pluripotency markers) was negative for iPSC-MSCs using flow cytometry. This indicated that there were no iPSCs in the derived iPSC-MSCs. Furthermore, iPSC-MSCs did not cause tumor formation and remained as a normal karyotype after cell expansion [18]. Therefore, iPSC-MSCs are promising candidate cells for regeneration medicine.

BMP2 is one of the most effective growth factors for bone repair [55,56]. BMP2 is a soluble glycoprotein that induces osteogenic differentiation. BMP2 initiates a signal transduction cascade when it encounters the target cells, for example, MSCs [55]. First, BMP2 binds its receptor at the cell membrane, which is a heterodimeric complex of type I and type II serine/threonine kinases. The activation of the receptor then leads to phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Smad proteins. Then, the osteogenic transcription factor Runx2 is increased and osteogenic proteins are synthesized [55]. Besides the capability of osteogenic induction, BMP2 had no significant side effect on MSC proliferation [57,58]. Clinical investigations demonstrated that recombinant human BMP2 (rhBMP2) was safe and effective for bone repair [59]. rhBMP2 has received approval of the FDA for clinical use in certain spinal fusion and facial defect applications [22,56]. Therefore, BMP2 is an ideal candidate growth factor for promoting bone regeneration.

When BMP2 was applied directly in vivo for bone defect repair, the cost was high because a large dose of BMP2 was needed. Furthermore, the locally delivered BMP2 was instable and the half-life of the protein was short [22]. A highly-promising alternative method for BMP2 delivery was to have BMP2 overexpressed in certain cells by the gene therapy technology. This allows a sustained release of BMP2 for high efficacy with a low cost. The selection of vectors which are used to carry foreign genetic material into other cells may influence the BMP2 expression. The plasmids and viral vectors are two most frequent choices [60]. Regarding the efficacy of gene therapy, the plasmid gene delivery is not as efficient as the viral method [21]. Gene therapy by viral vectors may ensure that a large amount of cells are infected without significant effects on cell viability. In addition, some viruses can integrate into the cell genome and enables stable expression of target gene. The most common viral vectors include adenovirus, retrovirus, and lentivirus [61]. Generally, the adenoviruses cannot be integrated into the host chromosomes and therefore only cause transient infection. The retroviral vectors have the capability of stable infection by integrating the exogenous gene into the host genome [62]. Lentiviruses, belonging to the large family of retroviruses and most of which are derived from HIV, can efficiently transduce both non-dividing and dividing cells, while the other retroviruses can only transduce dividing cells [61–63]. Recent advances in the safety and efficacy of lentiviral vectors make them a promising choice for gene therapy [63,64]. Clinical studies using lentiviral vectors for gene transfer have been effectively carried out [61,63]. In the present study, the lentiviral vector was used to transduce iPSC-MSCs to express BMP2 stably for the first time. BMP2-iPSC-MSCs produced significant level of BMP2 protein constantly. A million BMP2-iPSC-MSCs produced approximately 3 ng of human BMP2 daily, comparable to a previous BMP2 transgene study [23]. Osteogenic differentiation was verified via great increases in ALP, collagen I and OC expressions, as well as bone mineral synthesis by the cells. In each case, the increase was greater for the BMP2-iPSC-MSC group than the iPSC-MSC group, indicating successful BMP2 gene modification. It should be noted that the OC expression decreased from 1 d to 7 d, and then increased from 7 d to 14 d. A similar trend was observed in previous studies [41, 53]. A possible reason for this trend was that the osteogenic supplements in culture medium may trigger a rapid but transient high OC expression in the first day or two, which would then gradually fall to a lower level. This could result in a higher but transient OC peak at 1 d and a lower OC expression at 7 d. Then, persistent osteogenic differentiation would eventually lead to a substantial increase in OC from 7 d to 14 d.

Efforts were made to biofunctionalize CPC scaffold to enhance cell function [41,51]. Compared with traditional CPC, incorporation of biofunctional agents, such as the cell-adhesive RGD peptide, improved cell attachment, osteogenic differentiation, and bone mineral synthesis [41,51]. For this purpose, RGD peptide was immobilized on chitosan via a carbodiimide reaction, which was then incorporated into CPC. The modified CPC could greatly promote the attachment and osteogenesis of MSCs derived form human ESCs [41]. In the present study, iPSC-MSCs were seeded on RGD-CPC scaffold for the first time. iPSC-MSCs attached and survived well on RGD-CPC scaffold. BMP2 gene-modification did not cause significant difference on cell viability on RGD-CPC. Therefore, the combined use of BMP2-iPSC-MSCs and RGD-CPC may be a promising approach for bone regeneration. However, CPC scaffold properties such as porosity, pore size and interconnections are critical factors for cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation. Therefore, whether or not this BMP2-iPSC-MSC/RGD-CPC construct is a promising approach for bone regeneration needs to be tested in vivo. Hence, further investigations are required to evaluate the BMP2-iPSC-MSC/RGD-CPC construct in an animal model.

5. Conclusions

This study genetically modified human iPSC-MSCs for BMP2 release, and investigated BMP2 gene-modified iPSC-MSC seeding on RGD-CPC scaffold. BMP2-iPSC-MSCs stably expressed high BMP2 levels by lentiviral vector-mediated gene transduction. BMP2 gene modification enhanced osteogenic differentiation, without compromising cell growth kinetics and cell cycle stages. In addition, BMP2 delivery by gene therapy had no adverse effect on iPSC-MSC attachment and growth on RGD-CPC scaffolds. The overexpression of BMP2 greatly increased the osteogenic differentiation and bone mineral production of iPSC-MSCs on RGD-CPC. Therefore, BMP2 gene modified iPSC-MSCs are promising candidate cells for bone tissue engineering, and the BMP2-iPSC-MSC/RGD-CPC constructs have potential for bone regeneration in a wide range of orthopedic and craniofacial applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. Linzhao Cheng of the Johns Hopkins University for kindly providing the iPSCs, and Drs. Michael D. Weir, Laurence C. Chow, Carl G. Simon and Xuedong Zhou for help. This study was supported by NIH NIDCR R01 DE14190 and R21 DE22625 (HX), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Grant No. 81030034 (ZZ), and University of Maryland School of Dentistry bridge funding (HX).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhao L, Weir MD, Xu HH. Human umbilical cord stem cell encapsulation in calcium phosphate scaffolds for bone engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3848–3857. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marolt D, Knezevic M, Novakovic GV. Bone tissue engineering with human stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;1:10. doi: 10.1186/scrt10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meinel L, Karageorgiou V, Fajardo R, Snyder B, Shinde-Patil V, Zichner L, et al. Bone tissue engineering using human mesenchymal stem cells: effects of scaffold material and medium flow. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:112–122. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000007796.48329.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao JJ, Giannobile WV, Helms JA, Hollister SJ, Krebsbach PH, Longaker MT, et al. Craniofacial tissue engineering by stem cells. J Dent Res. 2006;85:966–979. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao JJ, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Mikos AG, Atala A. Regenerative medicine: Translational approaches and tissue engineering. Boston, MA: Artech House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson PC, Mikos AG, Fisher JP, Jansen JA. Strategic directions in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2827–2837. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikos AG, Herring SW, Ochareon P, Elisseeff J, Lu HH, Kandel R, et al. Engineering complex tissues. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3307–3339. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvidson K, Abdallah BM, Applegate LA, Baldini N, Cenni E, Gomez-Barrena E, et al. Bone regeneration and stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:718–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsberg E, Kong HJ, Hirano Y, Smith MK, Albeiruti A, Mooney DJ. Regulating bone formation via controlled scaffold degradation. J Dent Res. 2003;82:903–908. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao J, Radin S, Reilly G, Leboy PS, Ducheyne P. Solution-mediated effect of bioactive glass in poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)-bioactive glass composites on osteogenesis of marrow stromal cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;75:794–801. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanti RM, Li WJ, Nesti LJ, Wang X, Tuan RS. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: biological properties, characteristics, and applications in maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1640–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao Y, Mareddy S, Crawford R. Clonal characterization of bone marrow derived stem cells and their application for bone regeneration. Int J Oral Sci. 2010;2:127–135. doi: 10.4248/IJOS10045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baksh D, Yao R, Tuan RS. Comparison of proliferative and multilineage differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from umbilical cord and bone marrow. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1384–1392. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung Y, Bauer G, Nolta JA. Concise review: Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: progress toward safe clinical products. Stem Cells. 2012;30:42–47. doi: 10.1002/stem.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lian Q, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhang HK, Wu X, Zhang Y, et al. Functional mesenchymal stem cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells attenuate limb ischemia in mice. Circulation. 2010;121:1113–1123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei H, Tan G, Manasi, Qiu S, Kong G, Yong P, et al. One-step derivation of cardiomyocytes and mesenchymal stem cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2012;9:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villa-Diaz LG, Brown SE, Liu Y, Ross AM, Lahann J, Parent JM, et al. Derivation of mesenchymal stem cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells cultured on synthetic substrates. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1174–1181. doi: 10.1002/stem.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blau HM, Springer ML. Gene therapy--a novel form of drug delivery. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1204–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J, Ries J, Gelse K, Kloss F, von der Mark K, Wiltfang J, et al. Bone regeneration in critical size defects by cell-mediated BMP-2 gene transfer: a comparison of adenoviral vectors and liposomes. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1089–1098. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu C, Chang Q, Zou D, Zhang W, Wang S, Zhao J, et al. LvBMP-2 gene-modified BMSCs combined with calcium phosphate cement scaffolds for the repair of calvarial defects in rats. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:1965–1973. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira E, Potier E, Vaudin P, Oudina K, Bensidhoum M, Logeart-Avramoglou D, et al. Sustained and promoter dependent bone morphogenetic protein expression by rat mesenchymal stem cells after BMP-2 transgene electrotransfer. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;24:18–28. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v024a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors. 2004;22:233–241. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu WK, Sugiyama O, Park SH, Conduah A, Feeley BT, Liu NQ, et al. Lentiviral-mediated BMP-2 gene transfer enhances healing of segmental femoral defects in rats. Bone. 2007;40:931–938. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virk MS, Conduah A, Park SH, Liu N, Sugiyama O, Cuomo A, et al. Influence of short-term adenoviral vector and prolonged lentiviral vector mediated bone morphogenetic protein-2 expression on the quality of bone repair in a rat femoral defect model. Bone. 2008;42:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.12.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ducheyne P, Qiu Q. Bioactive ceramics: the effect of surface reactivity on bone formation and bone cell function. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilliar RM, Filiaggi MJ, Wells JD, Grynpas MD, Kandel RA. Porous calcium polyphosphate scaffolds for bone substitute applications -- in vitro characterization. Biomaterials. 2001;22:963–972. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foppiano S, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW, Saiz E, Tomsia AP. The influence of novel bioactive glasses on in vitro osteoblast behavior. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71:242–249. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reilly GC, Radin S, Chen AT, Ducheyne P. Differential alkaline phosphatase responses of rat and human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells to 45S5 bioactive glass. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4091–4097. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deville S, Saiz E, Nalla RK, Tomsia AP. Freezing as a path to build complex composites. Science. 2006;311:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.1120937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown WE, Chow LC. A new calcium phosphate water setting cement. In: Brown PW, editor. Cements research progress. Westerville, OH: Am Ceram Soc.; 1986. pp. 352–379. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barralet JE, Gaunt T, Wright AJ, Gibson IR, Knowles JC. Effect of porosity reduction by compaction on compressive strength and microstructure of calcium phosphate cement. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohner M, Baroud G. Injectability of calcium phosphate pastes. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1553–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Link DP, van den Dolder J, van den Beucken JJ, Wolke JG, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. Bone response and mechanical strength of rabbit femoral defects filled with injectable CaP cements containing TGF-β1 loaded gelatin microparticles. Biomaterials. 2008;29:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ginebra MP, Driessens FC, Planell JA. Effect of the particle size on the micro and nanostructural features of a calcium phosphate cement: a kinetic analysis. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3453–3462. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shindo ML, Costantino PD, Friedman CD, Chow LC. Facial skeletal augmentation using hydroxyapatite cement. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:185–190. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880140069012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman CD, Costantino PD, Takagi S, Chow LC. BoneSource hydroxyapatite cement: a novel biomaterial for craniofacial skeletal tissue engineering and reconstruction. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;43:428–432. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199824)43:4<428::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon CG, Jr, Guthrie WF, Wang FW. Cell seeding into calcium phosphate cement. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:628–639. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bohner M, Gbureck U, Barralet JE. Technological issues for the development of more efficient calcium phosphate bone cements: a critical assessment. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6423–6429. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen W, Zhou H, Weir MD, Tang M, Bao C, Xu H. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cell seeding on calcium phosphate cement-chitosan-RGD scaffold for bone repair. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:915–927. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metallo CM, Ji L, de Pablo JJ, Palecek SP. Retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein signaling synergize to efficiently direct epithelial differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:372–380. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chou BK, Mali P, Huang X, Ye Z, Dowey SN, Resar LM, et al. Efficient human iPS cell derivation by a non-integrating plasmid from blood cells with unique epigenetic and gene expression signatures. Cell Res. 2011;21:518–529. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng L, Hansen NF, Zhao L, Du Y, Zou C, Donovan FX, et al. Low incidence of DNA sequence variation in human induced pluripotent stem cells generated by nonintegrating plasmid expression. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kutner RH, Zhang XY, Reiser J. Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:495–505. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, Zhou H, Weir MD, Xu HH, Chen Q, Trotman CA. Fast-degradable microbeads encapsulating human umbilical cord stem cells in alginate for muscle tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:2303–2314. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D'Amario D, Fiorini C, Campbell PM, Goichberg P, Sanada F, Zheng H, et al. Functionally competent cardiac stem cells can be isolated from endomyocardial biopsies of patients with advanced cardiomyopathies. Circ Res. 2011;108:857–861. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.241380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balcerzak M, Hamade E, Zhang L, Pikula S, Azzar G, Radisson J, et al. The roles of annexins and alkaline phosphatase in mineralization process. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:1019–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu HH, Quinn JB, Takagi S, Chow LC, Eichmiller FC. Strong and macroporous calcium phosphate cement: Effects of porosity and fiber reinforcement on mechanical properties. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57:457–466. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20011205)57:3<457::aid-jbm1189>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park K, Joung Y, Park K, Lee S, Lee M. RGD-Conjugated chitosan-pluronic hydrogels as a cell supported scaffold for articular cartilage regeneration. Macromol Res. 2008;16:517–523. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thein-Han W, Liu J, Xu HH. Calcium phosphate cement with biofunctional agents and stem cell seeding for dental and craniofacial bone repair. Dent Mater. 2012;28:1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu J, Xu HH, Zhou H, Weir MD, Chen Q, Trotman CA. Human umbilical cord stem cell encapsulation in novel macroporous and injectable fibrin for muscle tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:4688–4697. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou H, Xu HHK. The fast release of stem cells from alginate-fibrin microbeads in injectable scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7503–7513. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thein-Han W, Xu HH. Collagen-calcium phosphate cement scaffolds seeded with umbilical cord stem cells for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2943–2954. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith DM, Cooper GM, Mooney MP, Marra KG, Losee JE. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 therapy for craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:1244–1259. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181843312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Razzouk S, Sarkis R. BMP-2: biological challenges to its clinical use. N Y State Dent J. 2012;78:37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meinel L, Hofmann S, Betz O, Fajardo R, Merkle HP, Langer R, et al. Osteogenesis by human mesenchymal stem cells cultured on silk biomaterials: Comparison of adenovirus mediated gene transfer and protein delivery of BMP-2. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4993–5002. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raida M, Heymann AC, Gunther C, Niederwieser D. Role of bone morphogenetic protein 2 in the crosstalk between endothelial progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:735–739. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.18.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin X, Zamora PO, Albright S, Glass JD, Pena LA. Multidomain synthetic peptide B2A2 synergistically enhances BMP-2 in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:693–703. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yla-Herttuala S, Alitalo K. Gene transfer as a tool to induce therapeutic vascular growth. Nat Med. 2003;9:694–701. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage FH, et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kay MA. State-of-the-art gene-based therapies: the road ahead. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:316–328. doi: 10.1038/nrg2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matrai J, Chuah MK, VandenDriessche T. Recent advances in lentiviral vector development and applications. Mol Ther. 2010;18:477–490. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]