Abstract

How insulin binds to its receptor is unknown despite decades of investigation. Here, we employ chiral mutagenesis–comparison of corresponding d and l amino acid substitutions in the hormone–to define a structural switch between folding-competent and active conformations. Our strategy is motivated by the T → R transition, an allosteric feature of zinc-hexamer assembly in which an invariant glycine in the B chain changes conformations. In the classical T state, GlyB8 lies within a β-turn and exhibits a positive ϕ angle (like a d amino acid); in the alternative R state, GlyB8 is part of an α-helix and exhibits a negative ϕ angle (like an l amino acid). Respective B chain libraries containing mixtures of d or l substitutions at B8 exhibit a stereospecific perturbation of insulin chain combination: l amino acids impede native disulfide pairing, whereas diverse d substitutions are well-tolerated. Strikingly, d substitutions at B8 enhance both synthetic yield and thermodynamic stability but markedly impair biological activity. The NMR structure of such an inactive analogue (as an engineered T-like monomer) is essentially identical to that of native insulin. By contrast, l analogues exhibit impaired folding and stability. Although synthetic yields are very low, such analogues can be highly active. Despite the profound differences between the foldabilities of d and l analogues, crystallization trials suggest that on protein assembly substitutions of either class can be accommodated within classical T or R states. Comparison between such diastereomeric analogues thus implies that the T state represents an inactive but folding-competent conformation. We propose that within folding intermediates the sign of the B8 ϕ angle exerts kinetic control in a rugged landscape to distinguish between trajectories associated with productive disulfide pairing (positive T-like values) or off-pathway events (negative R-like values). We further propose that the crystallographic T → R transition in part recapitulates how the conformation of an insulin monomer changes on receptor binding. At the very least the ostensibly unrelated processes of disulfide pairing, allosteric assembly, and receptor binding appear to utilize the same residue as a structural switch; an “ambidextrous” glycine unhindered by the chiral restrictions of the Ramachandran plane. We speculate that this switch operates to protect insulin–and the β-cell–from protein misfolding.

Insulin, a small globular protein containing three disulfide bridges, plays a central role in the regulation of vertebrate metabolism. The hormone is stored in the pancreatic β cell as a zinc hexamer and functions in the bloodstream as a zinc-free monomer. The functional surface of insulin has long been the object of speculation. Despite decades of investigation by mutagenesis and X-ray crystallography (1, 2), structures of insulin and insulin analogues do not consistently predict relative potencies (3–5). Such anomalies suggest that a change in structure occurs on receptor binding. Here, chiral mutagenesis–comparison of corresponding d and l amino acid substitutions of an invariant glycine–is employed to investigate the interrelation of structure and function in the B chain.1 Experimental design is motivated by the classical T → R transition, an allosteric feature of zinc-insulin hexamers (6–8).2 Remarkably, chiral stabilization of the native T state (the predominant conformation in solution; refs 9 and 10) markedly impairs its binding to the insulin receptor (IR).3 Because the extent of impairment exceeds that ordinarily encountered in studies of mutant insulins (1, 2, 11), we suggest that the d substitution impairs an R-like conformational switch required for high-affinity receptor binding.

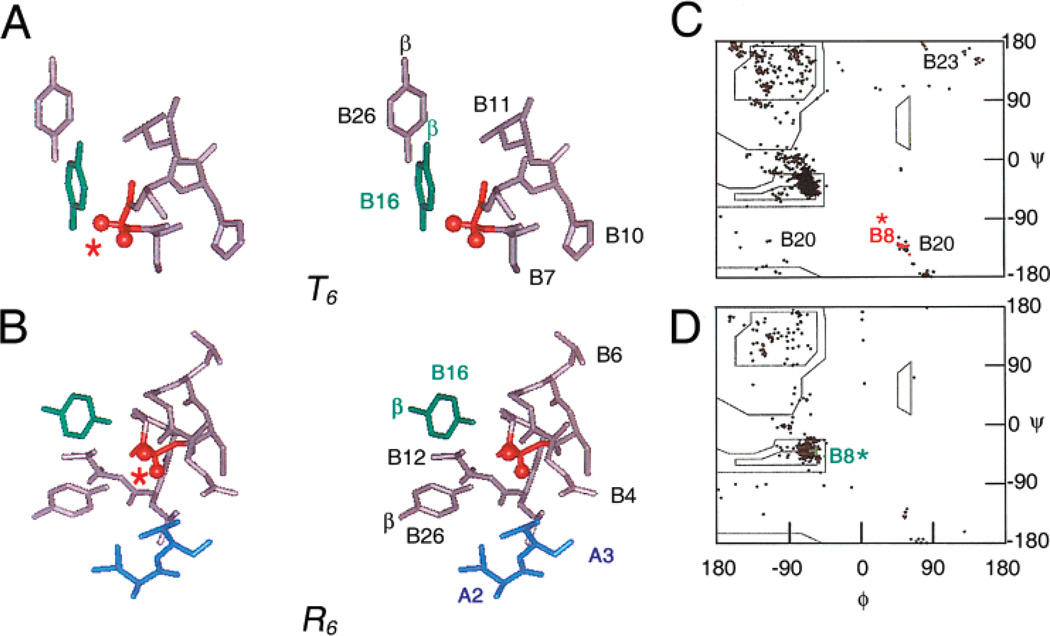

We focus on an invariant glycine in the B chain (GlyB8; arrow in Figure 1A). This glycine follows a motif-specific cysteine (CysB7) and is broadly conserved among vertebrate insulin-like polypeptides (Figure 2). The environment of GlyB8 differs between the two classes of crystallographic protomers, T and R (Figure 1B). Whereas residues B7–B10 form a type II′ β turn in the T state (Figure 1C; ref 1), the same residues lie within an extended α helix in the alternative R state (Figure 1D; refs 6 and 7). GlyB8 lies at the junction of this chameleon segment (12) and the central α helix (B9–B19). Although the B8 junction is exposed on the surface of the T and R state protomers, local packing schemes thus differ among crystal forms (Figure 3A,B). These contrasting environments are associated with different B8 ϕ dihedral angles (Figure 3C,D): positive in the T state (like a d amino acid; 56.4° ± (4.1 among multiple crystal structures) and negative in the R state (like an l amino acid; −63.0° ± 3.2) (see Supporting Information). Such Ramachandran relationships motivate investigation of whether d and l amino acid substitutions would induce stereospecific perturbations of folding or function. In particular, because the structure of the insulin monomer in solution closely resembles the crystallographic T state (4, 10, 13), would d substitutions at B8 stabilize the β turn, and if so, would such a chiral “lock” enhance or impair biological activity? Conversely, what would be the effects of l substitutions? Molecular modeling suggests that in a T-like protomer d or l side chains would project into solvent (Figure 1E); in a putative R-like protomer, l substituents would be exposed, whereas d side chains would be buried (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Overview of insulin structure. (A) Sequence of human insulin indicating invariant glycine in B chain (GlyB8; arrow). Substitutions in monomeric DKP-insulin template are shown in magenta. Disulfide bridges are indicated by lines. (B) Cylinder model of insulin showing the T state (left) and R state (right) in the crystallographic dimer. Black balls indicate positions of GlyB8. (C and D) Ribbon models of T6 (C) and R6 (D) zinc hexamers. Asterisks indicate positions of GlyB8; the variable B1–B8 segment is highlighted in silver. The central zinc ions are coordinating side chains of HisB10 and are also shown. (E and F) Molecular surfaces of T state (E) and R state (F) protomers indicating B8 site (boxes) and model of d-AlaB8 substitution (methyl group in white and Hα in yellow). Also shown are LeuA13 (magenta) and LeuB6 (green). The A and B chains are otherwise shown in red and blue, respectively. 4INS (1) and 1EV3 (39) were used in panels C and D.

Figure 2.

Glycine is invariant at position B8 among insulin sequences and also conserved among insulin-like growth factors (IGF–I and IGF–II). Comparison of representative B chain or B domain sequences is shown; B8 residues are boxed (asterisk).

Figure 3.

Structural relationships in crystal structures of insulin surrounding GlyB8. (A and B) In T state protomers GlyB8 participates in a β turn (red asterisk in A) whereas in R state protomers, B8 is part of an α-helix (red asterisk in B). In the T state protomer, B8 is near TyrB26 of same molecule (B8 Cα–Oζ B26 distance 5.3 Å) and dimer-related TyrB16 (green); in the R state protomer, B8 is near these residues and in addition ValB12 (an (i, i +4) contact in α-helix) and A chain of adjoining molecule in hexamer (IleA2 and ValA3; blue). For clarity, Cβ atoms of aromatic side chains are as indicated. Coordinates were obtained from T3R3f zinc hexamer (Protein Databank 1TYL; ref 75). (C and D) Ramachandran maps derived from crystal structures (Protein Databank 4INS (1), 1TYL (75), and 1TRZ (36)). Whereas in T state protomers GlyB8 has ϕ dihedral angles (red; C), in the R state protomers, GlyB8 belongs to an extended α-helix and so exhibits negative ϕ values (green; D).

To address these questions, we first employ combinatorial peptide chemistry to compare effects of l and d amino acid substitutions on insulin foldability. A novel in vitro selection is designed based on chain combination (14); mass spectrometry (MS) is used to distinguish between allowed and disallowed B chain sequences 15). Respective peptide libraries containing mixtures of d or l substitutions at B8 exhibit a stereospecific perturbation of insulin chain combination: l amino acids impede native disulfide pairing, whereas diverse d substitutions are well-tolerated. We then extend these findings to characterize representative diastereomeric pairs of B8 analogues. d Substitutions enhance the thermodynamic stability of insulin but markedly impair its biological activity, whereas unstable l analogues can be highly active.4 Remarkably, a single d methyl group attached to the surface of insulin is shown to stabilize the native structure of insulin in solution (ΔΔGu > 1 kcal/mol) but impair its receptor binding by 1000-fold. Because this decrement far exceeds effects of mutations on the protein surface at neighboring sites (1, 11), these observations suggest that the canonical T state of insulin represents an inactive conformation: the introduced d methyl group acts as a spanner in the works to block an R-like change in B8 conformation on receptor binding. We propose that this invariant glycine in the B chain functions as a Ramachandran switch between folding-competent and active conformations, mirroring aspects of the classical T → R allosteric transition (6, 7). We thus envisage that the flexibility of GlyB8 both protects the β-cell from toxic protein misfolding and enables high-affinity hormone-receptor recognition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Human insulin was provided by Eli Lilly and Co. (Indianapolis, IN). Isolated A chain tetra-S-sulfonate derivatives were obtained by oxidative sulfitolysis of insulin followed by separation of S-sulfonated A and B chains as described (16). B chain analogues were prepared (16) using solid-phase synthesis 17, 18). Chain combination (19) was effected by interaction of the S-sulfonated derivative of the A chain (1.25 mM) and B chain (0.5 mM) in 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 10.6, 4 mL) in the presence of dithiothreitol (4.5 mM) (15, 18). Each analogue was purified by a combination of size-exclusion chromatography (Bio-Gel P-4 in 3 M acetic acid) and preparative rp-HPLC (C18). DKP analogues each contain three DKP substitutions to prevent self-association of insulin (HisB10 → Asp, ProB28 → Lys, and LysB29 → Pro; refs 13 and 20). Nonstandard analogue d-p-amino-PheB8-B1-biotinyl-amidocaproyl-DKP-insulin (21) was kindly provided by P. G. Katsoyannis. Two-disulfide analogues of insulin containing pairwise substitution of cystine A7–B7 by serine were likewise synthesized as described (22). Fidelity of synthesis was in each case verified by MS.

Peptide Libraries

Mixtures of Fmoc-protected d or l amino acids were prepared by mixing equimolar solutions of each residue type except cysteine, glycine, and proline. Respective B chain libraries were synthesized using Fmoc chemistry by dividing, coupling, and recombining peptide resins to ensure equimolarity of the 17 B chain analogues within each peptide pool. The predicted diversity of the libraries was verified by MALDI-TOF MS. Respective libraries were combined with the native A chain (in S-sulfonate form); chain combination was initiated on addition of dithiothreitol and monitored by MALDI-TOF MS (Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems). Similar efficiencies of MS detection were verified in control studies of representative d and l analogues obtained by conventional synthesis (d-AlaB8-insulin and l-AlaB8-insulin). Proper disulfide pairing in a representative d analogue (d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin) was verified by NMR spectroscopy and in a representative l analogue (l-SerB8-insulin) by X-ray crystallography (J. Whittingham and G. G. Dodson, personal communication).

Receptor-Binding Assays

Relative activity is defined as the ratio of analogue to wild-type human insulin required to displace 50 % of specifically bound 125I-human insulin. A human placental membrane preparation containing the IR was employed as described (23). In all assays, the percentage of tracer bound in the absence of competing ligand was less than 15% to avoid ligand-depletion artifacts.

Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation equilibrium and sedimentation velocity measurements were conducted at 22 °C using a Beckman analytical ultracentrifuge (model XLI) as described (24). The proteins were made 0.4 mM in 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) and 50 mM KCl. Sedimentation equilibrium studies were conducted at 16 000 and 30 000 rpm. Molecular-weight values were calculated using a partial specific volume of 0.73 mL/g and density 1 g/cm3. Sedimentation velocity studies were conducted at 60 000 rpm, and results were fitted with the program DCDT Plus. The dimerization-defective analogue KP-insulin (ProB28 → Lys and LysB29 → Pro; Humalog (24)) was employed as a control.

Visible Absorption Spectroscopy

To probe the TR transition of Co2+-substituted insulin hexamers, the d–d optical absorption bands of Co2+ (a characteristic feature of a tetrahedral complex) were monitored as described (25–27). Solutions contained 0.2 mM insulin or insulin analogue in a buffer consisting of 0.07 mM CoCl2 and 50 mM phenol in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8). Spectra were obtained in the presence and absence of 0.8 M NaSCN.

CD Spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were obtained using a thermister-controlled Aviv spectropolarimeter equipped with an automated titration unit for guanidine denaturation studies. CD samples for wavelength spectra contained 25–50 µM insulin analogue in 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) and 50 mM KCl. For equilibrium denaturation studies, samples were diluted to 5 µM; guanidine-HCl was employed as denaturant as described (28). Data were obtained at 4 °C. Guanidine denaturation data were fitted by nonlinear least squares to a two-state model (29).

NMR Spectroscopy

High-resolution studies of insulin as a monomer in aqueous solution have been made possible by substitutions that destabilize dimer- and hexamer-forming surfaces but do not hinder receptor binding (10, 13, 20, 30). DKP-insulin is employed here as a template for study of B8 analogues (substitutions are shown in magenta in Figure 1A). Spectra were obtained at 600 MHz as described (13, 28, 30) at pH 7.0 and 25 °C; pH 8.0 and 32 °C; and in 20% v/v deuterioacetic acid, pH 1.9 and 25 °C. Resonance assignment was based on homonuclear 2-D NOESY (mixing times 80 and 200 ms), total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY; mixing time 55 ms), and double-quantum filtered correlated spectroscopy (DQF–COSY) spectra. Helix-related hydrogen bonds were inferred from the pattern of protected amide resonances as observed in D2O solution containing 20% deuterioacetic acid (31).

Crystallization Trials

Crystals of variant zinc-insulin hexamers containing d-AlaB8 substitutions were sought by hanging-drop vapor diffusion using well-established T6 and ostensible R6 conditions (7, 32) as follows.

(i) T6 Conditions

Under a series of conditions permitting growth of well-ordered single crystals of native insulin over two weeks at room temperature, the d-AlaB8 variant exhibited unusually rapid growth of multiple small crystals leading in 2 days to clusters unsuitable for X-ray diffraction studies. For these trials, the proteins were made 10 mg/mL in 0.02 M HCl and mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution consisting of 100 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.4–8.9), 10–15% acetone, and 0.08–0.12% zinc acetate.

(ii) Ostensible R6-Like Conditions

Crystals of d-AlaB8-insulin suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained under conditions resembling those that ordinarily lead to growth of wild-type crystals containing R6 hexamers. The crystals were grown in the presence of a 1:2.5 ratio of Zn2+ to protein monomer and a 3.7:1 ratio of phenol to protein monomer in Tris-HCl buffer as described (33). Drops consisted of 1 µL of protein solution (10 mg/mL in 0.02 M HCl) mixed with 1 µL of reservoir solution (0.02 M Tris-HCl, 0.05 M sodium citrate, 5% acetone, 0.03% phenol, and 0.01% zinc acetate at pH 8.8). Each drop was suspended over 1 mL of reservoir solution. Crystals were obtained at room temperature after 2 weeks. Preliminary diffaction data from 17.4 to 2.5 Å resolution were collected at room temperature using an Raxis II area detector with CuKα radiation, located in the Department of Biochemistry, University of Chicago. Data were processed with programs DENZO (version 1.9.6) and SCALEPACK (version 1.9.6). Crystals belong to space group R3 with equivalent hexagonal unit-cell dimensions a = b = 80.84 Å and c = 38.84 Å, corresponding to one dimer per asymmetric unit. These dimensions are characteristic of a T3R3f hexamer (see Results). Control crystallization trials of wild-type human insulin under the same conditions yielded crystals belonging to the same space group but containing R6 hexamers as expected. Crystals of l-AlaB8-insulin were not sought due to low synthetic yields.

Molecular Modeling

Distance-geometry/simulated annealing calculations (DG/SA) were performed using the program DG-II as described (5); restrained molecular dynamics (RMD) calculations were performed using X-PLOR (34).

RESULTS

Our results are presented in three parts. The use of d- and l B chain libraries is described in part I and extended to characterize representative (d, l) B8 analogues. Their structures, stabilities, and receptor-binding activities are investigated in part II. Pairwise substitution of a key cystine by serine is employed in part III to explore the coupling between B8 chirality and disulfide pairing. In addition to the B8 peptide libraries, the present study employs ten B8 analogues obtained by individual syntheses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Receptor–Binding Affinities of B8 Analoguesa

| analogue | rel. affinity (%) | analogue | rel. affinity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| human insulin (HI) | 100 (7) | DKP-insulin (DKP-Ins) | 160 ± 15 (2) |

| l-AlaB8-HIb | 1.0 ± 0.4 (3) | l-SerB8-DKP-Insc | 90 ± 6 (3) |

| d-AlaB8-HI | 0.11 ± 0.02 (4) | d-SerB8-DKP-Ins | 1.1 ± 0.1 (3) |

| l-AlaB8-DKP-Ins | 3.6 ± 0.6 (4) | d-PmpB8-DKP-Insd | 0.52 ± 0.11 (3) |

| d-AlaB8-DKP-Ins | 0.17 ± 0.04 (5) | d-ArgB8-DKP-Ins | 0.054 ± 0.002 (3) |

| [SerA7, SerB7]-DKP-Inse | <0.01 | d-AlaB8-[SerA7, SerB7]-DKP-Ins | <0.01 |

| l-AlaB8-[SerA7, SerB7]-DKP-Ins | <0.01 |

The dissociation constant for native human insulin is 0.4–0.5 nM. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of replicates.

Kristensen and colleagues reported that AlaB8-insulin binds to the isolated receptor ectodomain with relative affinity 3 ± 2%.

Similar but lower values have recently been obtained by Feng and colleagues in studies of a l-AlaB8-HI analogue (35, 86).

Pmp designates para-amino-Phe. The analogue also contains an N-terminal biotinyl-amidocaproyl modification at B1, which is associated itself with a small decrement in activity (21). Correction for this effect predicts a relative affinity of 0.63 ± 0.13% for the B8 modification.

Value obtained from ref 22.

I. Combinatorial Chain Combination

Chain combination provides a functional selection for foldable B chain variants as outlined in Figure 4A. Allowed substitutions enable pairing with wild-type A chains to yield a two-chain product with characteristic molecular mass (ca. 5.8–6.0 kDa); disallowed substitutions cannot. Two libraries of B chains were synthesized, one containing diverse d amino acids at B8 and the other, l amino acids. Each contains 17 variants. Cysteine was excluded to avoid confounding disulfide bridges; proline was excluded due to its anomalous conformation properties. Neither library contained glycine, the wild-type residue. The peptides were protected by S-sulfonate modification; their diversity was verified by MS. Following addition of a 2:1 molar excess of the wild-type S-sulfonate-protected A chain, the chain combination was initiated by the addition of dithiothreitol and allowed to proceed under air oxidation for 24 h at 4 °C. The resulting d and l reaction mixtures were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 4D,E) in relation to a control reaction employing the wild-type B chain. Whereas the B8 l amino acid library yielded only a trace amount of insulin analogues (empty insulin region in Figure 4D), the d library by contrast resulted in native or enhanced foldability (Figure 4E). The d reaction mixture was subjected to gel filtration and partial rp-HPLC purification. All possible d-amino acid substitutions were detected by MS (Supporting Information). Among these substitutions, the polar side chain at B8 (such as d-Lys and d-Arg) was obtained at higher yield than nonpolar or aromatic side chains (such as d-Ala and d-Trp). All fractions exhibit very low affinity for the IR (<0.5% relative to insulin). Stereospecific interference with chain combination was verified in single syntheses of d-AlaB8 and l-AlaB8 insulin analogues (Figure 4B,C). The d-Ala88 substitution is associated with a 3-fold increase in the efficiency of chain combination. By contrast, following prolonged reaction times (48–72 h), the l-AlaB8 analogue was obtained and purified with a yield >30-fold lower than that of the d analogue. Native disulfide pairing was verified in part by peptide mapping following Staphylococcus aureus V8 protease digestion.5 Native disulfide pairing in a representative d analogue (d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin) was explicitly demonstrated by 2-D NMR spectroscopy. MALDI-TOF MS spectra of the purified d-AlaB8 and l-AlaB8 analogues indicated similar efficiencies of detection, suggesting that the original MS characterization of the d and l libraries faithfully reflects relative yields.

Figure 4.

Foldability as probed by combinatorial peptide synthesis with MS read out. (A) Functional-selection scheme based on insulin chain combination. B chain analogue or library of analogues is mixed with wild-type A chain to initiate specific disulfide pairing. Products are detected by mass. (B–E) MALDI-TOF MS spectra of the chain-combination reactions following 24 h at 4 °C. (B and C) Control reactions of l-AlaB8 (B) and d-AlaB8 (C) B chains. (D and E) Combinatorial reactions of l and d libraries at B8, respectively. Whereas l analogues undergo inefficient chain combination, productive pairing is observed to yield multiple diverse d substitutions at B8. MS spectra also detect oxidized A and B chains and A chain dimers (d).

II. Biochemical Characterization of Representative Analogues

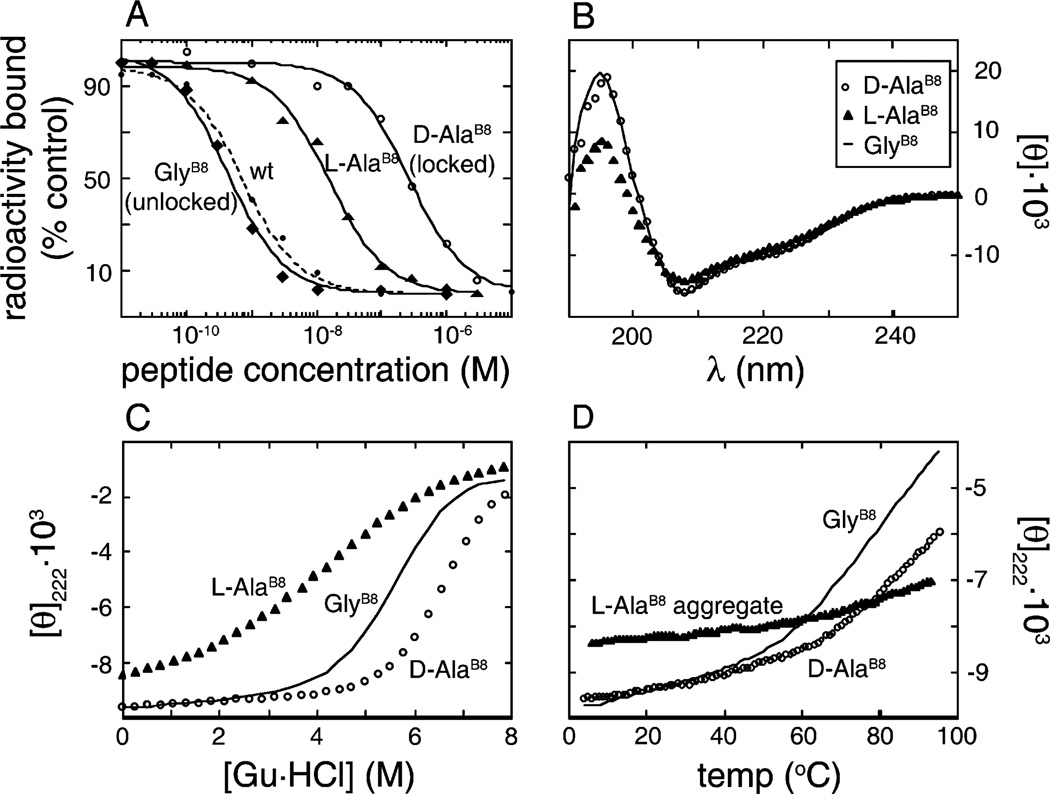

Both d and l AlaB8-insulin exhibit low receptor-binding activities (0.11 ± 0.02 and 1.0 ± 0.4%, respectively; Figure 5A and Table 1). The low activity of l-AlaB8-insulin is consistent with prior studies (11, 35). Both d and l-AlaB8-insulin are able to undergo the T → R transition in phenol-stabilized Co2+-insulin hexamers as probed by observation of phenol-dependent d–d transitions characteristic of the R state-specific tetrahedral metal-binding site (26, 27). The concentration of phenol was made 50 mM to favor formation of the R state (Materials and Methods). Although the spectral line shape of the d–d transitions in the d-AlaB8 hexamer is similar to that of wild-type Co2+-substituted R6 hexamers, their intensity is nevertheless reduced by about 2-fold (Supporting Information), suggesting predominant formation of T3R3f hexamers as the octahedral metal-binding site of a T3 trimer would not appreciably contribute to the d–d band. In accord with this observation, preliminary crystallographic studies of phenol-stabilized Zn2+-coordinated d-AlaB8-insulin hexamers grown under such conditions, although expected to form R6 hexamers, instead exhibit unit cell dimensions similar to those of T3R3f hexamers in the same crystal form (Supporting Information). In a given space group, these dimensions provide an empirical fingerprint of the hexamer type. The a and b dimensions (80.84 Å), for example, are similar to those of T3R3f PDB 1TRZ (80.64 Å; ref 36) and 1QJ0 (80.94 Å; ref 37), whereas rhombohedral crystals containing R6 hexamers exhibit distinct unit-cell dimensions (PDB 1ZEG, 1ZEH, and 1EV3; refs 38 and 39). As expected, preliminary analysis of the present crystals by molecular replacement is consistent with formation of a nativelike T3R3f containing three bound phenol molecules (Z.-l Wan and M. A. Weiss, unpublished results). Together, these spectroscopic and crystallographic observations suggest that the d substitution partially impairs the TR transition, arresting the hexamer at an intermediate stage of structural organization. Our results do not exclude formation of d-AlaB8 R6 hexamers at higher concentrations of phenol.

Figure 5.

Activity and stability of B8 analogues. (A) Receptor-binding titrations of DKP-insulin analogues relative to native human insulin (dashed line): GlyB8 (diamonds), l-AlaB8 (triangles), and d-AlaB8 (open circles). Relative affinities of these and other analogues are given in Table 1. (B) Far-UV CD spectra of DKP insulin analogues: GlyB8 (solid line), l-AlaB8 (triangles), and d-AlaB8 (open circles). (C and D) Guanidine (C) and thermal (D) denaturation studies of DKP-insulin analogues (symbols as in panel B). l-AlaB8 aggregates exhibit an anomalous thermal signature. Extent of folding was monitored by ellipticity at 222 nm. Receptor-binding and CD studies were conducted at 4 °C.

Wild-type insulin in solution undergoes self-association to yield dimers, tetramers, hexamers, and higher-order oligomers, which may be differently affected by d- or l substitutions at B8. To avoid such potentially confounding effects and to facilitate spectroscopic studies, d-AlaB8 and l-AlaB8 analogues were resynthesized in the context of DKP-insulin, an engineered monomer of high activity (13, 20, 30). The previous stereospecific difference in efficiency of chain combination was unaffected by the DKP substitutions, leading to enhanced yield of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin and more than tenfold lower yield of l-AlaB8-DKP-insulin. CD spectroscopy demonstrates that the d analogue retains native secondary structure (circles in Figure 5B), whereas the l analogue is perturbed: helical features at 222, 208, and 195 nm are attenuated (triangles in Figure 5B). Since GlyB8 does not reside in an α-helix in the native (T-like) structure in solution, the attenuated helix content of l-AlaB8-insulin implies nonlocal changes in conformation or dynamics. The d and l substitutions effect opposite changes in protein stability: l-AlaB8-insulin is more sensitive to denaturant-induced unfolding, whereas d-AlaB8-insulin is more robust (Figure 5C). Respective free energies of unfolding are given in Table 2. The thermodynamic changes are marked: respective ΔΔGu values are 1.5 ± 0.2 kcal/mol (d-AlaB8; “locked” in the native state) and −2.1 ± 0.3 kcal/mol (l-AlaB8). These ΔΔGu values are larger than those ordinarily encountered in studies of single amino acid substitutions in insulin (5, 23, 40, 41). Inversion of Cα chirality at B8 (i.e., comparison of d-AlaB8 and l-AlaB8 analogues) is thus associated with an extraordinary 4.1 ± 0.3 kcal/mol difference in stability. d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin also exhibits greater thermal stability than DKP-insulin (Figure 5D). Comparison of d-SerB8- and l-SerB8-DKP-insulin analogues yields similar trends in efficiency of chain combination, helix content, and stability (Table 2 and Supporting Information). d- and l-SerB8 analogues differ in stability by 3.9 ± 0.2 kcal/mol.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic Stabilities of B8 Analogues

| analogue | ΔGu (kcal/mol)a | Cmid (M)b | m (kcal/mol/M)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 0.84 ± 0.01 |

| DKP-insulin | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 0.84 ± 0.01 |

| l–AlaB8-DKP-Insd | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 0.95 ± 0.02 |

| d–AlaB8-DKP-Ins | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 0.66 ± 0.05 |

| l–SerB8-DKP-Ins | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 0.89 ± 0.02 |

| d–SerB8-DKP-Ins | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 0.51 ± 0.01 |

ΔGu indicates apparent change in free energy on denaturation in guanidine-HCL as extrapolated to zero denaturant concentration by a two-state model (29).

Cmid is defined as that concentration of guanidine-HCl at which 50% of the protein is unfolded.

The m value provides the slope in plotting unfolding free energy ΔGu versus molar concentration of denaturant; this slope is proportional to the protein surface area exposed on unfolding.

Abbreviation for DKP-insulin template.

d-AlaB8- and d-SerB8-DKP-insulin each exhibit low activities (0.17 ± 0.04 and 1.1 ± 0.1%, respectively; Table 1). Because of the favorable HisB10 → Asp substitution in the DKP template (20), the affinity of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin is almost 2-fold higher than that of d-AlaB8-insulin (0.11 ± 0.02%). Surprisingly, l-SerB8-DKP-insulin exhibits substantial receptor-binding activity (90% relative to human insulin), suggesting that the low activity of l-AlaB8 analogues is not a general property of l amino acid substitutions. The 1H NMR spectrum of l-AlaB8-DKP-insulin (Figure 6C) exhibits resonance broadening relative to spectra of DKP-insulin or d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin (Figure 6A,B). Studies of protein aggregation by equilibrium ultracentrifugation and sedimentation velocity indicate that (like DKP-insulin) the d-AlaB8 analogue is monomeric, whereas l-AlaB8-DKP-insulin forms predominantly dimers and higher-order oligomers at a protein concentration of 75 µM. Because self-association occurs despite the presence of the DKP substitutions (20), it is presumably mediated by non-native protein surfaces (see Discussion). By contrast, the quality of the 1H NMR spectrum of l-SerB8-DKP-insulin is similar to that of DKP-insulin and its d analogues (Supporting Information), indicating an initial absence of aberrant self-association. (Unlike DKP-insulin and d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin, whose NMR spectra remain unchanged after two weeks in solution, l-SerB8-DKP-insulin undergoes slow but progressive aggregation over several days at 25 °C, leading likewise to resonance broadening.) These findings suggest that the low activity of l-AlaB8 analogues is due to confounding aggregation and not directly related to B8 stereochemistry. Aggregation of the l-AlaB8 analogue is also associated with an anomalous thermal CD signature (Figure 5D).

Figure 6.

1H NMR studies of DKP-insulin analogues at 600 MHz at 25 °C (pH 7.4). (A) GlyB8, (B) d-AlaB8, and (C) l-AlaB8. Asterisk in panel B indicates position of d-AlaB8 methyl resonance (see Figure 7). The spectrum of the GlyB8 and d-AlaB8 analogues are similar whereas the l-Ala analogue undergoes aberrant aggregation.

The 1H NMR spectrum of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin is tractable by homonuclear NMR methods (42), permitting complete resonance assignment (Supporting Information). Chemical shifts are essentially identical to those observed in DKP-insulin; significant changes (magnitude >0.1 ppm) are observed only at neighboring residues CysB7 and SerB9 (Supporting Information). The novel d-AlaB8 spin system is well-resolved (Figure 7). The pattern of interresidue NOEs is likewise similar to that of DKP-insulin, in each case consistent with structures of T-state crystallographic protomers.6 Maintenance of T state-specific long-range interactions by the N-terminal arm of the B chain is demonstrated by the retention of interchain NOEs between the B1–A13 and B5–A10 side chains. The orientation of the B9–B19 α-helix relative to the A chain, as probed by a network of long-range NOEs in the hydrophobic core (Supporting Information), is also unaffected by the d-AlaB8 substitution. NOEs involving the β protons of the six cysteines are essentially identical to those observed in the spectrum of DKP-insulin, indicating maintenance of native disulfide pairing. As expected based on native models (Figures 1E and 3A), NOEs are observed from the β-CH3 group of d-AlaB8 to the amide protons of B11 and B12, one methyl resonance of ValB12, and the H∊ aromatic protons of TyrB26. The methyl group of d-AlaB8 is also likely to be near the methyl groups of ValA3 and LeuB11, but such cross-peaks are difficult to resolve in homonuclear 2-D NOESY spectra at 600 MHz.

Figure 7.

1H NMR TOCSY spectra of (A) DKP-insulin and (B) d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin highlighting novel d-Ala methyl resonance in analogue (asterisk in panel B). Spectra were acquired at 600 MHz at 32 °C and pD 7.6 (direct meter reading) with a TOCSY mixing time of 55 ms.

DG/RMD calculations verify that the solution structure of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin (Figure 8C) is similar to the native T state (Figure 8A) and essentially identical to that of DKP-insulin (Figure 8B) with the exception of the d-methyl group at B8 (yellow). The structure was calculated on the basis of 389 NOEs, 42 dihedral restraints, and 36 hydrogen-bond-related restraints (Supporting Information). The B8 Ramachandran angles in the DG/RMD ensemble are ϕ = 22.1 ± 5.2 and ψ = −103.5 ± 4.6; these values are similar but not identical to those characteristic of GlyB8 in crystallographic T state protomers. The positive ϕ value for d-AlaB8 stands in contrast to the classical α-helical conformation of l-AlaB14 in the NMR ensemble (ϕ −67.7 ± 3.6, ψ –39.0 ± 3.0). d-AlaB8 is shielded in part by the side chains of ValA3 (nearby despite the absence of explicit A3–B8 constraints), ValB12, and TyrB26. The solvent accessibility of the B8 methyl group (28 ± 13%) is lower than what would be predicted based on the wild-type crystallographic T state (ca. 70%) due to a small adjustment in the position of TyrB26. Because the C-terminal segment of the B chain appears to reorganize on receptor binding (see Discussion), this adjustment is unlikely to be of functional significance. The conserved side chains of ValA3, LeuB11, ValB12, and TyrB26 create a local nonpolar cup that partially surrounds d-AlaB8 (Figure 9). B11 is a critical component of the hydrophobic core (15), whereas the side chains of A3, B12, and B26 contribute to receptor binding (1, 18, 43); their spatial relationships in this or wild-type structures may be reorganized on receptor binding (2). Restraint information and statistical parameters are given in the Supporting Information. The nativelike structure of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin is in accord with its efficient folding (as probed by the increased yield of chain combination) and enhanced stability but stands in contrast to its 1000-fold decrement in receptor-binding activity relative to DKP-insulin (Table 1).

Figure 8.

d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin exhibits nativelike solution structure. (A) Collection of crystal structures showing superimposition of T state protomers (Protein Databank 4INS (1), 1TYL (75), 1PID (76), 1TRZ (36), and 1TYM (75)). The position of GlyB8 is highlighted in yellow. The B chain is otherwise shown in blue, and the A chain is red. Structure of truncated analogue des-pentapeptide[B26–B30]-insulin (DPI) is indicated by d’s at positions B1 and B25. (B) Solution structure of DKP-insulin (PDB 1LNP; ref 28). (C) Ensemble of DG/RMD structures of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin showing position of d-Ala side chain (yellow). The coloring scheme in panels B and C corresponds to that in panel A.

Figure 9.

Environment of d-AlaB8 side chain at protein surface. (A and B) Ribbon and space-filling models of representative structure of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin showing position of d-AlaB8 methyl group (tawny; sphere in panel A at 0.7 van der Waals radius) relative to side chains of ValA3 (red), ValB12 (dark blue), and TyrB26 (black). LeuB11 (magenta) lies behind B8 in core. The A chain is otherwise shown in gray and the B chain otherwise in blue. (C) Stereopair showing spatial relationships among residues A3, B8, B11, B12, and B26. The ensemble was aligned on these side chains to illustrate B8 pocket. Color scheme is the same as in panels A and B.

III. Importance of Cystine A7–B7

It is possible that the very low yields encountered in syntheses of l-AlaB8-insulin and other l variants are due to either (a) the low thermodynamic stabilities of the final products (Table 2) or (b) a kinetic block to disulfide pairing. In an effort to distinguish between these mechanisms, we investigated the role of neighboring cystine A7–B7. Pairwise substitution of A7 and B7 by serine has previously been shown to lead to a molten globule of marginal stability (ΔΔGu < 2 kcal/mol) but not impairment of specific pairing of the remaining four cysteines (22). Because the stability of the two-disulfide analogue is lower than that of l-AlaB8-DKP-insulin and yet efficient disulfide pairing is maintained, relative yields are unlikely to be under thermodynamic control. Substitution of GlyB8 by d or l-Ala in the context of [SerA7, SerB7]-DKP-insulin likewise enables analogous disulfide pairing without significant differences in yield. Specific pairing of cystines A20–B19 and A6–A11 was achieved in each case with yields 70–80% of that observed in wild-type chain combination. The absence of a stereospecific block to disulfide pairing indicates that the folding defect associated with l-AlaB8 is overcome by removal of the A7–B7 disulfide bridge. Conversely, the absence of stereospecific augmentation of disulfide pairing indicates that d-AlaB8 does not facilitate formation of noncontiguous cystines A6–A11 and A20–B19. Together, these findings suggest that in the wild-type pathway of disulfide pairing the B8 dihedral angle is critical in allowing or hindering formation of the A7–B7 disulfide bridge.7 In accord with past studies (22), the two disulfide analogues are essentially devoid of biological activity (relative affinities <0.01%; Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Glycine can be conserved at key sites in proteins because of its small size. The interior of the collagen triple helix, for example, can accommodate only glycine, rationalizing the conserved Gly–X–Y triplet repeat (44). Similarly, in myoglobin and hemoglobin, the close approach of the B and E helices leads to broad conservation of glycine at helix position B6 (45). The absence of a side chain also enables glycine to adopt either positive or negative ϕ dihedral angles and thus occupy regions of the Ramachandran plot unfavorable to the other amino acids. Insulin and insulin-like growth factors contain an invariant glycine in the B chain (GlyB8; asterisk in Figure 2) whose conformation switches as part of the T → R transition (Figure 3; refs 6 and 7). Although the physiological significance of this transition is unknown (as the R state has only been observed in zinc insulin hexamers and not among structures of IGFs or engineered insulin monomers; ref 8), we propose that this glycine is conserved to make possible a structural switch between folding-competent and active conformations of the hormone. Thus, impairment of the TR transition in a variant insulin hexamer by substitution of GlyB8 by d-Ala also impairs binding to the insulin receptor. The substitution nonetheless preserves the structure and enhances the stability of an engineered insulin monomer. We discuss these results from the complementary perspectives of stability, folding and function.

Stereospecific Stabilization of a Protein

Respective d and l substitutions at B8 give rise to large and opposite changes in thermodynamic stability (ΔΔGu; see Table 2). Why do d or l substitutions so markedly enhance or perturb stability? d-AlaB8 and d-SerB8 enhance the stability of DKP-insulin by 1.5 ± 0.2 and 0.9 ± 0.2 kcal/mol, respectively. We suggest that this gain in free energy has four sources. First, the d substitution may decrease the entropy of the unfolded state and hence the entropic penalty of folding. The extent of stabilization is greater than RT ln(2) (∼0.5 kcal/mol), the expected entropic effect of restricting a single glycine’s ϕ angle to half of the accessible Ramachandran plane. It is possible that a d substitution at B8 stabilizes a nascent β turn in the unfolded state, biasing the values of multiple dihedral angles and so increasing the resulting entropic benefit. Second, local interactions of the d side chain in the folded state may be favorable (or unfavorable). van der Waal contacts between d-AlaB8 and the neighboring side chains of ValA3, LeuB11, ValB12, and TyrB26, for example (Figure 9), may contribute to stability; this environment may be less favorable in the polar SerB8 analogue and so account for its lower stability. Third, possible damping of fluctuations elsewhere in the protein, presumed to be coupled to changes in the B8 dihedral angles, may strengthen multiple weak interactions; such an effect may be offset by an entropic penalty. Finally, a change in the topography and polarity of the B8-associated protein surface may alter its solvation properties. Of these four potential mechanisms, only the first–chiral restriction of the unfolded state–would be expected to be independent of the details of the folded state and to circumvent entropy–enthalpy compensation. Accordingly, it would be of interest in the future to test whether chiral substitution of a β turn in a globular protein may provide a general strategy for protein stabilization, and if so, whether the mechanism is primarily entropic. Such a strategy would extend established principles of medicinal chemistry widely employed in the stabilization of cyclic peptides.

The decrement in stability associated with l-AlaB8 or l-SerB8 substitutions (ΔΔGu 2.6 ± 0.3 and 3.0 ± 0.3 kcal/mol, respectively) is also likely to have complex origins. We imagine that a distorted local structure of the B7–B10 β turn is accompanied by transmitted perturbations in the helical structure of the protein. It is not clear from CD where the perturbations occur in the protein (i.e., in the neighboring B chain R-helix or in the A chain) and whether the attenuated CD signature reflects a discrete structural change (foreshortening of an R-helix) or a distributed dynamic destabilization without a change in helical endpoints. The CD spectrum of KP-insulin (containing substitutions ProB28 → Lys and LysB29 → Pro; ref 24), an analogue in clinical use as a rapid-acting insulin formulation (46), also exhibits an apparent attenuation of helix content even though crystallographic and NMR studies have demonstrated nativelike secondary structure (13, 47, 48). A molecular understanding of l-SerB8 analogues will require high-resolution NMR or crystallographic analysis of these distorted structures. It is noteworthy that the unfavorable l-amino acids are not accommodated at B8 (as might be imagined) simply by propagation of the B9–B19 α helix into the N-terminal segment (i.e., adoption of an extended R-like conformation). This possibility is excluded by the CD perturbations implying attenuation (rather than enhancement) of helix-related features. It would be intriguing if l-SerB8 is nevertheless accommodated in a high-affinity hormone–receptor complex by an R-like conformational change.

Protein Stability and Stereospecific Modulation of the TR Transition

Although the present study has focused on the insulin monomer, the biologically active species, our experimental design is stimulated by the extensive foundation of crystallographic studies of zinc-insulin hexamers. Such assemblies are remarkable for a ligand-dependent equilibrium among T6, T3R3f, and R6 hexamers (8). The TR transition is characterized by long-range conformational changes associated with a switch in the Ramachandran position of GlyB8. d Substitutions at B8 significantly stabilize the T-like conformation of an insulin monomer and would hence be expected to shift the equilibrium among T6, T3R3f, and R6 hexamers toward the T state. Such a shift is in accord with our observation of attenuated Co2+ d–d transitions, which are diagnostic of the R state-specific tetrahedral metal-binding site in phenol-stabilized hexameric complexes (25–27). These results suggest that–although d-AlaB8-insulin can indeed form an R state–the variant R state is less stable than the variant T state under conditions (high phenol concentration) in which wild-type insulin is almost entirely in the R6 conformation. The d-AlaB8 substitution thus impedes (but does not entirely prevent) both binding of an insulin monomer to the IR and the hexameric TR transition.

Crystallization trials of d-AlaB8-insulin zinc hexamers under conditions that ordinarily give rise to a wild-type R6 lattice instead yield T3R3f crystals. This result rationalizes the ca. 2-fold attenuation of the previous Co2+ d–d transitions and demonstrates that the TR transition has been interrupted at an intermediate stage. Although the molecular details of this structure have not been determined, the overall ability of d-AlaB8 to be accommodated within an Rf state-specific α helix would be consistent with studies of model helicogenic peptides by W. DeGrado and co-workers in which a single d-Ala was shown to be energetically well-tolerated within an α helix (49). Although local conformational adjustments may occur, such accommodation incurs only a modest cost in free energy (ΔΔGu 1 kcal/mol relative to l-Ala and 0.2 kcal/mol relative to glycine at the same peptide position). The ability of a canonical α-helix to accommodate one or more d amino acids has been elegantly demonstrated by Karle and co-workers in crystallographic studies of model peptides in helicogenic solvents (84). Impairment of the TR transition by d-AlaB8 is thus likely to have two mechanisms: marked chiral stabilization of the T state and modest chiral destabilization of the R state.

The crystal structure of d-AlaB8-insulin as a T3R3f hexamer promises to extend prior peptide studies (84) to define how a d amino acid is accommodated in an α helix within a large protein assembly. Substitution of GlyB8 by l-Ser is likewise compatible with either T or Rf conformation in crystallographic hexamers (J. Whittingham and G. G. Dodson, personal communication). We would expect such an l substitution to shift the equilibrium among T6, T3R3f, and R6 hexamers toward the R state. Although the Ramachandran plot is often interpreted in terms of forbidden regions, these considerations emphasize that d or l substitutions influence the relative thermodyamic stabilities of competing conformations rather than provide covalent locks to tether or exclude specific structures.

Because the solution structure of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin closely resembles the parent monomer and in turn the crystallographic T state, we initially sought to obtain crystals of d-AlaB8-insulin under a range of conditions suitable for growth of wild-type T6 crystals. Surprisingly, the analogue exhibited crystallization properties different from those of wild-type insulin: anomalously rapid growth of clusters of small crystals. Suitable T6 crystals of the analogue were therefore not obtained despite extensive trials. Accelerated crystallization, although a practical impediment to obtaining highly ordered single crystals, suggests that the d substitution enhances lattice growth either by stabilizing intermolecular contacts or damping structural fluctuations that otherwise retard the growth of wild-type crystals. It is possible that in the future suitable single T6 crystals of d-AlaB8-insulin can be obtained under conditions that are less favorable for wild-type crystallization, retarding the rate of crystallization to permit orderly growth of single crystals. Because the wild-type T6 crystal form has been found to diffract to atomic resolution (1, 50), such crystals would be of interest to enable comparative analysis of anisotropic B values and alternative side-chain conformations as probes of protein dynamics. It is also possible that at higher concentrations of phenol, d-AlaB8-insulin can be driven into the R6 state as the free energy of ligand binding compensates for chiral destabilization of the R-state-specific α-helix.

Insulin Chain Combination and the Folding of Proinsulin

In vivo insulin is the product of a larger single-chain precursor, designated proinsulin (86 residues; ref 51). Native disulfide pairing (A6–A11, A7–B7, and A20–B19) occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In vitro studies suggest that such pairing is directed exclusively by sequences in the A and B domains (14); the connecting peptide (35 residues) provides a passive tether. Combination of the isolated A and B chains has thus been studied as a peptide model of proinsulin-folding intermediates (28, 52). The present study of chain-combination efficiency exploits peptide libraries to demonstrate a stereospecific preference for d amino acids at B8. In fact, d-AlaB8 enhances the yield of chain combination by 3-fold; to our knowledge, such enhancement is without precedent in the literature of insulin synthesis. It is likely that even higher yields would be conferred by other members of the d library. Equally striking, the corresponding l library yields no productive sequences. Use of libraries containing all possible d or l side chains (exclusive of cysteine and proline) thus indicates that the key feature is the chirality of the α carbon (and hence preferred sign of the ϕ dihedral angle) rather than the size or chemical features of individual side chains. Representative l analogues can nonetheless be prepared in very low yield. The relevance of the peptide libraries to proinsulin is suggested by studies of the expression of a foreshortened single-chain analogue (porcine insulin precursor; 52 residues) in Saccharomyces cerevisciae: substitution of GlyB8 by l-Ala markedly impairs productive folding and secretion (35). It would be of future interest to extend these results to the folding and secretion of human proinsulin analogues by a transfected mammalian neuroendocrine cell line.

Together, our results suggest that the B8 conformation plays a critical role in the mechanism of disulfide pairing. Because d substitutions stabilize a native T-like fold (the structure of an isolated insulin monomer; refs 10 and 13), exclusion of l substitutions suggests that local nativelike structures are populated in the relevant protein-folding intermediates and serve to guide disulfide pairing. Although these intermediates are not well-characterized (53), pairwise substitution of cystine A7–B7 by serine leads to rescue of chain combination and essentially complete attenuation of stereospecific interference by l-AlaB8. This finding suggests that the B8 conformation is coupled to productive orientation of the adjoining CysB7. We speculate that a kinetic block to formation of the A7–B7 disulfide bridge leads to competing off-pathway events. The yield of insulin chain combination (like that of proinsulin folding; ref 54) is well-known to be limited by aberrant aggregation of partially folded species (28). Analogous partial unfolding, even in the presence of the three native disulfide bridges, may underlie the unexpected self-association of l-AlaB8-DKP-insulin and the slow aggregation of the l-SerB8-DKP-insulin NMR sample. Such aggregation is ordinarily mediated by the B chain (or B domain) and can lead to irreversible cross-β assembly of fibrils. It would be of future interest to investigate whether B8 l substitutions in proinsulin lead to formation of pathological electron-dense deposits in the endoplasmic reticulum in cell culture or accelerated aggregation or fibrillation in vitro. Such features are characteristic of a mutant proinsulin in a murine model of diabetes mellitus (the Akita mouse; ref 55).

The marked enhancement in the efficiency of chain combination associated with the d-AlaB8 substitution is unlikely simply to reflect the greater stability of the end product (the insulin analogue). Past syntheses of unrelated insulin variants of enhanced stability (such as AspB10-insulin and HisA8-insulin; 60, 68, 85) have exhibited only modest increases in yield (<20%). The magnitude of the increase in yields of AlaB8-insulin and AlaB8-DKP-insulin (3-fold) therefore suggests favorable kinetic control of the reaction. It is possible that the d substitution biases the conformation of a protein-folding intermediate to facilitate A7–B7 disulfide pairing (an example of on-pathway control). It is also possible that the d substitution impairs competing side reactions, such as formation of cyclic B chains, covalent B-chain dimers, or B-chain fibrils (off-pathway control). We speculate that both of these mechanisms are operative. On the one hand, because d substitutions stabilize disulfide pairing in the native state, it is reasonable to suppose that they also stabilize the productive orientation of CysA7 and CysB7 in a transition state. On the other hand, it is also plausible that d substitutions at B8 impede cross-β assembly of B chains. Such a unique combination of on- and off-pathway effects may account for the extraordinary stereospecific augmentation of yields observed in the present d-AlaB8 syntheses.

Induced Fit and the Active Conformation of Insulin

How insulin binds to the insulin receptor has long been the subject of speculation (1, 2). That classical structures represent inactive conformers has been suggested by studies of an inactive single-chain analogue (mini-proinsulin) in which a peptide bond tethers the C-terminal β strand of the B chain (LysB29) to the N-terminal α helix of the A chain (GlyA1; refs 3 and 56).8 On receptor binding, the β strand presumably detaches from the core to contact the receptor (4) and expose an otherwise hidden functional surface in the A chain (30, 33). The present study exploits chiral stabilization of the B7–B10 β turn by d-amino acid substitutions at B8 to provide a complementary example of an inactive analogue with nativelike structure. Substitution of GlyB8 by d-Ala or d-Ser enhances the thermodynamic stability of insulin but markedly impairs its binding to the insulin receptor (Table 2). As in mini-proinsulin (56), the extent of impairment is highly unusual among mutant insulins (1, 11). The solution structure of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin resembles wild-type insulin (and the parent DKP-insulin monomer; ref 13) with the exception of the protruding methyl group at B8. Although we cannot exclude that d side chains at B8 themselves introduce a steric clash at the receptor interface (see below), we propose that the severe decrement in binding reflects a chiral impediment to induced fit: the analogues are locked into an inactive T-like conformation. This model thus envisages that both the N- and the C-terminal segments of the B chain reorganize on receptor binding.9 Such reorganization would in each case expose nonpolar side chains that are otherwise inaccessible in the T state and so make possible a more extensive hormone–receptor interface. Whereas displacement of the C-terminal segment of the B chain would expose IleA2 and ValA3 (3, 4, 30, 33, 43, 65), reorganization of the B1–B8 segment may likewise enable IleA10, LeuA13, and LeuB6 to contact the receptor (Figure 1E,F; 2, 27, 69).

Why is steric clash unlikely to account for the inactivity of B8 d analogues? This model seems implausible for several reasons. First, single amino acid substitutions on the surface of insulin generally affect receptor binding by less than 100-fold. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the protein surface, for example, yields a range of relative receptor-binding affinities between 30% (LeuA13 → Ala) and 405% (ArgB22 → Ala) (11). Even at presumed sites of van der Waals contact between insulin and the IR, enlarging the size of a side chain by one methyl group typically has only modest effects. Examples are provided by critical conserved valines in α helices: ValA3 and ValB12. Substitution of valine by isoleucine or allo-isoleucine leads to a one-methyl protrusion of one branch or the other. In each case, the respective receptor binding affinities are decreased by less than 10-fold (see Supporting Information; refs 18 and 43). Similarly, substitution of ValA3 or ValB12 by t-leucine (which substitutes Hβ by a third methyl group) perturbs receptor binding by less than tenfold (18, 43).10 Accommodation of additional methyl substituents at B12 is of particular interest in light of its proximity to B8 (in both T and R states; Supporting Information). Other sites near B8 also tolerate marked changes in side-chain volume as follows. (i) Only modest changes in affinity are observed on substitution of SerB9 by the larger side chains of Asn or Asp (57). (ii) Substitution of HisB5 (near B8 in the structure of DPI; refs 58 and 59) by Asn or Ala is similarly well-tolerated. (iii) Substitution of HisB10 by Asn or Leu leads to 2- and 3-fold decrements in receptor binding; AspB10 enhances binding whereas LysB10 impairs binding by 7-fold, presumably due to favorable or unfavorable long-range electrostatic interactions (60, 61). Given these quantitative trends, the 1000-fold decrement in activity caused by d-AlaB8 seems anomalous and unlikely to be due to rigidity of packing near this part of the insulin surface. Indeed, whereas the steric-clash model envisages a snug fit between GlyB8 and the insulin receptor, we instead imagine that this site adjoins a cavity between respective protein surfaces. This model would rationalize the relative affinities of d-SerB8-DKP-insulin: although serine is larger than alanine, the residual binding of the d-SerB8 analogue is 10-fold higher than that of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin. Such enhancement, difficult to reconcile with the steric-clash model, might arise from the introduction of a new interaction between the serine side chain and an otherwise uncontacted wall of the cavity, partially offsetting the d-associated chiral impairment. Similarly, the bulky side chain of d-p-amino-Phe (Pmp) is accommodated at B8 with less impairment than that caused by d-AlaB8 (Table 1), presumably due to favorable interactions in the putative B8-associated cavity.

Insulin analogues of extremely low activity ordinarily fall into two classes. The first are substitutions that lead to transmitted structural perturbations, presumably impairing both local and nonlocal hormone–receptor contacts. Examples include substitution of α helical contact residues ValA3 or ValB12 by glycine (relative affinities 0.1–0.2 and 0.32%; refs 18, 43, and 62), expected to destabilize the helical segment (40, 62). Substitution of a framework aromatic side chain in the hydrophobic core (TyrA19 → Ala), expected to disrupt tertiary structure, likewise impairs receptor binding by 1000-fold (11). Similarly, pairwise substitution CysA7 and CysB7 by serine (hence removing the A7–B7 disulfide bridge) leads to a molten partial fold whose activity is reduced by at least 5000-fold (13). The present NMR studies demonstrate that d-AlaB8 analogues do not fall into this class as the solution structure of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin is essentially identical to that of the parent monomer (13). The observed confluence of native structure and very low activity is reminiscent of single-chain insulin analogues in which the C-terminus of the B chain is connected to the N-terminus of the A chain directly or by a short linker (3, 56, 63, 64). This topological constraint is envisaged to hinder induced fit rather than impose a local steric clash. We propose an analogy between such a topological restraint and chiral restriction of the flexibility of GlyB8 by a d substitution. Consistent with the previous discussion of the thermodynamics of the TR transition, also impaired by d-AlaB8, we imagine that the 1000-fold decrement in binding of d-AlaB8 analogues arises in two ways: from chiral stabilization of the initial inactive T state and from the cost of accommodating d-AlaB8 in an induced R-like α helix (49). In essence, induced fit is impaired because the initial state is harder to leave and the final state is less favorable to enter.

The induced-fit hypothesis at the C-terminal region of the B chain is supported by the high activities of analogues that exhibit structural perturbations of the B chain. Substitution of PheB24 (which anchors the C-terminal β strand to the core; ref 1) by glycine leads to an altered segmental structure with near-native activity (4, 65).11 Further, the activity of insulin is enhanced by chiral substitution of PheB24 by d-Phe or d-Ala (20, 66); these substitutions appear to be incompatible with native structure. The present study has yielded analogous findings at B8, which suggest a second site of conformational change in the N-terminal region of the B chain. Whereas the nativelike d-AlaB8-stabilized T state is essentially inactive, the l-SerB8-distorted structure exhibits high activity despite its attenuated α helix content and lower stability. We imagine that structural distortions associated with d substitutions at B24 or l substitutions at B8 facilitate induced fit of the respective C- or N-terminal segments of the B chain and so are compatible with high activity. It would be of future interest to investigate the solution structures of these analogues.

Limitations of Conventional Mutagenesis

The present study illustrates a limitation of alanine scanning mutagenesis. The low activity of l-AlaB8-insulin (ref 11 and present results) is likely to reflect aberrant aggregation rather than local structural changes. Because l-SerB8-DKP-insulin is initially monomeric but exhibits a similar decrement in stability and CD-detected helix content, rapid aggregation is a particular feature of the AlaB8 analogue. Such aggregation was unanticipated as the DKP substitutions disallow classical self-association: inversion of B28–B29 destabilizes the dimer-related β sheet, whereas the substitution HisB10 → Asp destabilizes the hexamer-forming interface (20, 24, 48, 67). That these substitutions do not prevent self-association of AlaB8-DKP-insulin implies that aggregation is mediated by distorted protein surfaces. Interestingly, l-SerB8 is compatible with nativelike assembly of zinc-insulin hexamers and crystallization (J. Whittingham and G. G. Dodson, personal communication). Native zinc-mediated assembly presumably protects l-SerB8-insulin from the slow aggregation observed in NMR samples of l-SerB8-DKP-insulin. With respect to the different properties of l-Ala and l-Ser analogues, it may be relevant that generally among protein crystal structures serine is more likely than alanine to exhibit positive ϕ angles.

Confounding effects of structural distortion have previously been encountered in alanine scanning mutagenesis of insulin (11). At some sites, Ala variants could not be expressed, presumably due to misfolding and degradation in the yeast expression system (11). Kinetic barriers to disulfide pairing in vitro can also block synthetic chain combination (16, 68). Of particular interest, substitution of invariant side chain IleA2 by Ala permits robust expression (11) but leads to segmental unfolding of the A1–A8 α helix (5). In this case, substitution by allo-IleA2 enabled the specific contribution of this side chain to be resolved (30, 33). Detachment or reorganization of the C-terminal segment of the B chain, as envisaged previously, would expose IleA2 to engage the receptor. Analogous reorganization of the B1–B8 segment would likewise expose the central surface of the A chain (A10–A13) to provide an additional contact surface (2, 69). The total chemical synthesis of insulin permits use of nonstandard amino acids to extend the ordinary repertoire of site-directed mutagenesis. The use of stereoisomers such as allo-Ile (30, 43) and d amino acids, as exemplified here, may be of general utility in studies of synthetic proteins (70).

CONCLUSION

Important insight into the informational content of protein sequences has been obtained through genetic analysis of allowed and disallowed substitutions (71, 72). Application of random cassette mutagenesis to peptide libraries, pioneered by Kent and co-workers (15), provides a chemical approach to dissecting determinants of foldability. In the present study, the ability of B chain variants to combine with the wild-type A chain provides a functional selection. Advances in both synthetic methodologies and MS sequencing methods may enable this approach to be extended to multiple sites in the A and B chains. Such studies are motivated by the hypothesis that the evolution of insulin sequences is constrained in part by foldability: complementary requirements for specific disulfide pairing and against toxic misfolding. The present study has established that l and d substitutions at position B8 exhibit striking stereospecific modulation of synthetic yields and thermodynamic stabilities. We speculate that the flexibility of GlyB8 serves to protect proinsulin from misfolding and aberrant aggregation in the β-cell.

The functional implications of the present study transcend our initial goals pertaining to combinatorial chain combination and protein folding. AlaB8-DKP-insulin provides a novel example of an insulin analogue with native structure but very low activity. Previous examples include mini-proinsulin (whose structure is tethered by a peptide bond between the A and B chains; ref 3), a nonstandard main-chain analogue containg an ester linkage at B25 (26, 73), and the chiral analogue allo-IleA2-insulin (30, 33). Each of these structures provides evidence for induced fit in receptor binding. We propose that GlyB8 functions as a structural switch to enable both specific disulfide pairing and high-affinity receptor binding. The proposed switch recapitulates a key aspect of the classical T → R transition (8): a ligand-dependent reorganization of the insulin hexamer remarkable for a change in the ϕ angle of GlyB8 from positive (as preferred by d amino acids) to negative (as preferred by l amino acids). It would be of future interest to address whether other features of the R state (such as its extended B1–B19 α helix or change in conformation of cystine A7–B7) would also be induced on receptor binding. Although the receptor-bound conformation of insulin is likely to be neither completely T-like nor completely R-like, we anticipate that similar sites of conformation change will be utilized. If so, future cocrystal structures of insulin–receptor complexes will validate the prescient vision of Dorothy Hodgkin and colleagues, whose studies of zinc insulin crystals provided a model of conformational change (74). The pioneering perspective of the Hodgkin school (1) thus suggests that d amino acid substitutions at B8 act as a chiral spanner in the works of receptor recognition.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank P. G. Katsoyannis for support and advice regarding peptide synthesis; M. DeFelippis (Eli Lilly and Co.) for ultracentrifuge studies and the gift of human insulin; B. H. Frank, Y.-M. Feng, and J. Whittingham for communication of results prior to publication; and P. Arvan, T. L. Blundell, P. De Meyts, G. G. Dodson, A. Fersht and D. F. Steiner for helpful discussions. M.A.W. thanks C. M. Dobson and M. Karplus for encouragement. This article is a contribution from the Cleveland Center for Structural Biology. These studies were stimulated in part by historical remarks of Prof. Dorothy C. Hodgkin on the 20th anniversary of the determination of the crystal structure of insulin (The University of York, York, England, 1989). We dedicate this article to her memory.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Diabetes Research and Training Center at the University of Chicago (S.H.N. and M.Z.) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health to P. G. Katsoyannis (DK56673) and M.A.W. (DK409049 and DK069764).

The coordinates of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin will be deposited on acceptance in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession number pending).

Chiral mutagenesis of an invariant side chain in the A chain (IleA2) has previously been employed to investigate a hidden functional surface (30, 43). An allo-IleA2 analogue (in which the chirality of the β carbon is inverted) exhibits native structure but low activity (30, 33). The present study extends this approach to the polypeptide main chain.

The crystallographic T → R transition is characterized by a change in the secondary structure of the B1–B8 segment from extended (T state) to α-helix (R state). This reorganization is coupled to a change in the conformation of GlyB8 and handedness of cystine A7-B7. The sulfur atoms of the latter are exposed in the T state but buried in a nonpolar crevice in the R state. Whereas the structure of an isolated insulin in solution resembles the T state (10, 13), R state features have been observed only in zinc (and cobalt-substituted) hexamers. In particular, minor helix-related NOEs in the B1–B8 segment diagnostic of a subpopulation of R state conformers have not been detected in an insulin monomer in solution (10, 13, 33). The relevance of the T → R transition to the function of insulin as a monomer is unknown (7).

Abbreviations: CD, circular dichroism; DG, distance geometry; DKP-insulin, insulin analogue containing three substitutions in B chain (AspB10, LysB28, and ProB29); DQF–COSY, double-quantum-filtered correlated spectroscopy; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; IGF–I, insulin-like growth factor I; IR, insulin receptor; kDa, kilo-Dalton of mass; MALDI, matrix assisted laser desorption ionization; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; MS, mass spectrometry; NOEs, nuclear Overhauser enhancements; NOESY, NOE spectroscopy; RMD, restrained molecular dynamics; rp-HPLC, reverse-phase HPLC; SA, simulated annealing; RMSD, root-mean-square deviation; rpm, revolutions per minute; TOCSY, total correlation spectroscopy; TOF, time-of-flight; and UV, ultra-violet. Amino acids are designated by standard one- and three-letter codes.

A preliminary description of d and l B8 libraries was presented at the 1997 American Peptide Symposium (77). l-Alanine has also been introduced at B8 by biosynthetic expression of a single-chain precursor in yeast (11, 86). l-AlaB8 was associated with lower yield and impaired receptor binding by ∼30-fold in accord with the present results.

This protocol verifies the presence of cystine A20-B19 but does not distinguish between potential bridges A6–A11 or A7–A11. The MS read-out (Figure 4A) does not distinguish between native pairing and possible disulfide isomers.

The NOESY spectrum of d-AlaB8-DKP-insulin contains some additional interresidue contacts that are very weak or not observed in DKP-insulin but consistent with crystal structures of wild-type insulin (Supporting Information). The increased intensity of these NOEs may reflect damping of fluctuations by the d side chain. Stabilization of the protein is not accompanied by accentuated dispersion of 1H NMR chemical shifts.

The kinetic hypothesis is in accord with prior studies indicating that chain combination is in part under kinetic control (28) and that pairing of cystine A7–B7 plays a critical role in the oxidative folding pathway of insulin-like polypeptides (78, 79).

Mini-proinsulin refolds more efficiently than does proinsulin to achieve native disulfide pairing (80). Its enhanced foldability mirrors a loss of biological activity (64): the tethered native state is presumably constrained from reorganizing on receptor binding (3). Analogous (but less stringent) tethering has been described in an analogue containing a chemical cross-link between the ∊-amino group of LysB29 and the α-amino group of GlyA1 (63).

The T → R transition is also characterized by a small displacement of the C-terminal B chain β strand away from the A chain, breaking the B25 NH••••O=C A19 hydrogen bond observed in the T state (1). The two modes of induced fit proposed to occur in the N- and C-terminal segments of the B chain, although spatially separated in the protein, may in part be correlated (G. G. Dodson, personal communication).

Whereas substitution of ValB12 by Leu likewise impairs receptor binding by only less than 20-fold (16), LeuA3-insulin exhibits an unusual 500-fold decrease (43, 81), indicating limited flexibility around the presumed A3-binding pocket (82). A site of clinical mutation causing diabetes mellitus (83), ValA3 is largely buried in a crevice between chains that is distant from the B8-associated surface. The crystal structure of LeuA3-insulin (as an R6 zinc hexamer) is essentially identical to that of wild-type insulin (82).

Two structural models of GlyB24 analogues have been proposed in which the C-terminal segment is either detached from the core (4) or aberrantly attached via non-native contacts by PheB25 (65). Reassessment of these models suggests that the unanchored segment is primarily disordered but able to make transient contacts with the core (Q.-x. Hua and M. A.Weiss, manuscript in preparation).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Nine figures illustrating disulfide pairing and structural relationships in insulin crystals, visible absorption spectra of cobalt-substituted hexamers, additional CD and NMR spectra, diagonal plot of NOEs, and summary of NMR sequential assignment. Nine tables providing B8 dihedral angles, summary of mutations at sites neighboring B8, crystallographic unit-cell dimensions, NMR resonance assignments, statistical information pertaining to DG/RMD ensemble, and restraints. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker EN, Blundell TL, Cutfield JF, Cutfield SM, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Hodgkin DM, Hubbard RE, Isaacs NW, Reynolds CD. The structure of 2Zn pig insulin crystals at 1.5 Å resolution. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. London Ser. 1988;319:369–456. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1988.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Meyts P, Whittaker J. Structural biology of insulin and IGF–I receptors: implications for drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2002;1:769–783. doi: 10.1038/nrd917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derewenda U, Derewenda Z, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Bing X, Markussen J. X-ray analysis of the single chain B29-A1 peptide-linked insulin molecule. A completely inactive analogue. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;220:425–433. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hua QX, Shoelson SE, Kochoyan M, Weiss MA. Receptor binding redefined by a structural switch in a mutant human insulin. Nature. 1991;354:238–241. doi: 10.1038/354238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu B, Hua QX, Nakagawa SH, Jia W, Chu YC, Katsoyannis PG, Weiss MA. A cavity-forming mutation in insulin induces segmental unfolding of a surrounding α-helix. Protein Sci. 2002;11:104–116. doi: 10.1110/ps.32102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley G, Dodson E, Dodson G, Hodgkin D, Mercola D. Structure of insulin in 4-zinc insulin. Nature. 1976;261:166–168. doi: 10.1038/261166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derewenda U, Derewenda Z, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Reynolds CD, Smith GD, Sparks C, Swenson D. Phenol stabilizes more helix in a new symmetrical zinc insulin hexamer. Nature. 1989;338:594–596. doi: 10.1038/338594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brader ML, Dunn MF. Insulin hexamers: new conformations and applications. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1991;16:341–345. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90140-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua QX, Narhi L, Jia W, Arakawa T, Rosenfeld R, Hawkins N, Miller JA, Weiss MA. Native and non-native structure in a protein-folding intermediate: spectroscopic studies of partially reduced IGF-I and an engineered alanine model. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;259:297–313. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen HB, Ludvigsen S, Kaarsholm NC. Solution structure of an engineered insulin monomer at neutral pH. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8836–8845. doi: 10.1021/bi960292+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristensen C, Kjeldsen T, Wiberg FC, Schaffer L, Hach M, Havelund S, Bass J, Steiner DF, Andersen AS. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:12978–12983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minor DL, Jr., Kim PS. Measurement of the β-sheet-forming propensities of amino acids. Nature. 1994;367:660–663. doi: 10.1038/367660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua QX, Hu SQ, Frank BH, Jia W, Chu YC, Wang SH, Burke GT, Katsoyannis PG, Weiss MA. Mapping the functional surface of insulin by design: structure and function of a novel A chain analogue. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;264:390–403. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsoyannis PG, Tometsko A. Insulin synthesis by recombination of A and B chains: a highly efficient method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1966;55:1554–1561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.6.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muir TW, Dawson PE, Fitzgerald MC, Kent SBH. Probing the chemical basis of binding activity in an SH3 domain by protein signature analysis. Chem. Biol. 1996;3:817–825. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu SQ, Burke GT, Schwartz GP, Ferderigos N, Ross JB, Katsoyannis PG. Steric requirements at position B12 for high biological activity in insulin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2631–2635. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barany G, Merrifield RB. In: The Peptides. Gross E, Meienhofer J, editors. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa SH, Tager HS, Steiner DF. Mutational analysis of invariant valine B12 in insulin: implications for receptor binding. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15826–15835. doi: 10.1021/bi001802+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chance RE, Hoffman JA, Kroeff EP, Johnson MG, Schirmer WE, Bormer WW. In: Peptides: Synthesis, Structure, and Function; Proceedings of the Seventh American Peptide Symposium. Rich DH, Gross E, editors. Rockford, IL: Pierce Chemical Co.; 1981. pp. 721–728. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoelson SE, Lu ZX, Parlautan L, Lynch CS, Weiss MA. Mutations at the dimer, hexamer, and receptor-binding surfaces of insulin independently affect insulin–insulin and insulin–receptor interactions. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1757–1767. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu B, Hu SQ, Chu YC, Nakagawa SH, Whittaker J, Katsoyannis PG, Weiss MA. Diabetes-associated mutations in insulin: consecutive residues in the B chain contact distinct domains of the insulin receptor. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8356–8372. doi: 10.1021/bi0497796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua Q-X, Nakagawa SH, Jia W, Hu SQ, Chu Y-C, Katsoyannis PG, Weiss MA. Hierarchical protein folding: asymmetric unfolding of an insulin analogue lacking the A7–B7 interchain disulfide bridge. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12299–12311. doi: 10.1021/bi011021o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss MA, Hua Q-X, Jia W, Nakagawa SH, Chu Y-C, Hu S-Q, Katsoyannis PG. Activities of monomeric insulin analogues at position A8 are uncorrelated with their thermodynamic stabilities. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40018–40024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeFelippis MR, Bakaysa DL, Bell MA, Heady MA, Li S, Pye S, Youngman KM, Radziuk J, Frank BH. Preparation and characterization of a cocrystalline suspension of [LysB28,ProB29]-human insulin analogue. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 1998;87:170–176. doi: 10.1021/js970285m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]