Abstract

Seed extracts of Carthamus tinctorius L. (Asteraceae), safflower, have been traditionally used to treat coronary disease, thrombotic disorders, and menstrual problems but also against cancer and depression. A possible effect of C. tinctorius compounds on tryptophan-degrading activity of enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) could explain many of its activities. To test for an effect of C. tinctorius extracts and isolated compounds on cytokine-induced IDO activity in immunocompetent cells in vitro methanol and ethylacetate seed extracts were prepared from cold pressed seed cakes of C. tinctorius and three lignan derivatives, trachelogenin, arctigenin and matairesinol were isolated. The influence on tryptophan breakdown was investigated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Effects were compared to neopterin production in the same cellular assay. Both seed extracts suppressed tryptophan breakdown in stimulated PBMC. The three structurally closely related isolates exerted differing suppressive activity on PBMC: arctigenin (IC50 26.5 μM) and trachelogenin (IC50 of 57.4 μM) showed higher activity than matairesinol (IC50 >200 μM) to inhibit tryptophan breakdown. Effects on neopterin production were similar albeit generally less strong. Data show an immunosuppressive property of compounds which slows down IDO activity. The in vitro results support the view that some of the anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer and antidepressant properties of C. tinctorius lignans might relate to their suppressive influence on tryptophan breakdown.

Keywords: Carthamus tinctorius; Asteraceae; Safflower; Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase; Neopterin

Introduction

The first and rate limiting step of the tryptophan catabolism in mammals is regulated by the enzymes tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which catalyze the conversion of tryptophan to N-formyl kynurenine. Whereas TDO is mainly located in the liver, IDO is more widely distributed in the organism (Chen and Guillemin 2009). During immune activation and inflammation IDO is mainly up-regulated by Th1-type cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and this is detectable locally and systemically (Schroecksnadel et al. 2006), whereas in healthy conditions, the expression and activity of IDO in humans is low.

Tryptophan breakdown due to IDO activity is involved in several physiological and pathophysiological conditions which are associated with immune activation. Decreased levels of tryptophan lead, together with the effect of some of its catabolites, to immune tolerance via dendritic cells due to increased generation of regulatory T cells. Thus, tryptophan breakdown by IDO appears to be deeply involved in immunoregulatory processes (Chen et al. 2008) and inactivation of effector T cells (Soliman et al. 2010). Additionally, the catabolites of tryptophan, such as 3-hydroxykynurenine, kynurenic acid and quinolinic acid, are neuroactive and are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of the AIDS-dementia complex, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, complex partial seizures, depression, anorexia and schizophrenia (Stone 2001). Tryptophan is also the substrate of the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) pathway and its breakdown leads to reduced synthesis of serotonin which is related to depression, as observed, e.g., in cancer patients during treatment with IFNs (Byrne et al. 1986; Schroecksnadel et al. 2006). Therefore, IDO is a highly relevant target for the treatment of several diseases: in tumor therapy, IDO inhibitors are considered to be useful as effective adjuvants (Muller et al. 2005). In neurological disorders, IDO inhibition can reduce the production of the neurotoxic tryptophan metabolites (Takikawa 2005).

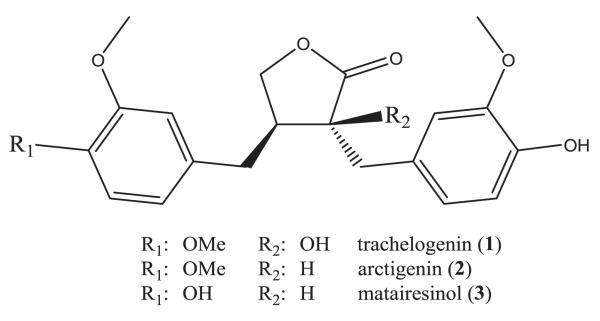

The herbaceous plant Carthamus tinctorius (Safflower), belonging to the Asteraceae family, has been used in traditional Chinese medicine to invigorate the blood and release stagnation, to promote circulation and menstruation (Pharmacopoeia of PRC 2010) and to treat neuropsychological disorders such as major depression (Zhao et al. 2009). In the Mediterranean area, it plays a role in the treatment of cancer and is known for its antihelmintic, antiseptic, diuretic and febrifugal properties (von Bruchhausen 2007). Previously, a methanolic extract of safflower seeds and lignans thereof were reported to exhibit cytotoxicity against three cancer cell lines (Bae et al. 2002). Based on these previous findings and the ethnopharmacological use of Safflower, the three major lignans trachelogenin, arctigenin, and matairesinol (Fig. 1) were isolated and pharmacologically investigated for their ability to interfere with activation of IDO in freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Jenny et al. 2011). Using this assay, extracts of Hypericum perforatum (Winkler et al. 2004a) and alkaloid compounds of Uncaria tomentosa (Winkler et al. 2004b) have already been demonstrated to suppress PBMC responses, and as a consequence IDO activity and neopterin production were diminished.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of compounds trachelogenin (1), arctigenin (2) and matairesinol (3).

Material and methods

Isolation of compounds

The cold-pressed seeds of C. tinctorius were donated from Stöger GmbH, 2164 Neuruppersdorf 65, Austria. A.o. Prof. Dr. J. M. Rollinger identified the plant material according to the monograph 6.4/2386 in the European Pharmacopoeia (European Pharmacopeia 2008). A voucher specimen (JR-20091002-A1) is deposited at the herbarium of the Institute of Pharmacy/Pharmacognosy, Leopold Franzens University, Innsbruck, Austria.

Cold-pressed seed oil cake of Carthamus tinctorius (1 kg) was macerated while shaking (100 moves/min) at room temperature with 2 l of methanol five times for 15 h each time. Obtained extracts were combined, evaporated to 400 ml, and extracted with 100 ml hexane. The methanol layer was dried, suspended in water and extracted with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. For further purification, the ethyl acetate layer (18.03 g) was subjected to a silica gel column (9 × 18 cm, 434.7 g). As mobile phases, petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, and methanol were used as a stepwise gradient yielding twelve fractions (A1–A12). The eluates were analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) with toluol, ethyl acetate, formic acid 3:1:0.2 (v:v:v) and detection by UV 254 nm, UV 366 nm, vanillin/sulfuric acid reagent).

Fraction A3 (649 mg) was subjected to a second silica gel column (2.8 × 40 cm, 301.2 g), using a stepwise gradient of petroleum ether, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and methanol, yielding 15 fractions (B1–B15). The analysis of eluates was performed by TLC (dichloromethane, acetone, formic acid 7:2:0.1 (v:v:v); detection by UV 254 nm, UV 366 nm, vanillin/sulfuric acid reagent).

Over a preparative LOBAR system (LiChroprep RP-18, 240 × 10 mm, 40–63 μm), trachelogenin could be isolated from fraction B8 (77.1 mg) using water (A) and methanol (B) as mobile phases applying the following gradient: from 26% B to 50% B in 192 min, to 80% B in 80 min, to 98% B in 12 min for another 36 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The separation was monitored by UV detection at 221 nm (Agilent HP UV detector series 1100, Böblingen, Germany). Arctigenin and matairesinol could be isolated from fraction B7 (150.3 mg) over the same LOBAR system. All three lignans were finally cleaned up by Sephadex® LH-20 CC (mobile phase acetone) resulting in 21.8 mg of trachelogenin, 4.2 mg arctigenin and 5.8 mg matairesinol, respectively.

The identity of the isolated compounds was determined by 1- and 2-D NMR spectroscopy, LC–MS and the measurement of the optical rotation in comparison with literature values (Boldizsar et al. 2010; Fischer et al. 2004). Purity was determined by HPLC and found to be ≥95%. All reagents were of purissimum or analytical quality and purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) unless otherwise specified. Purissimum grade solvents were distilled before use.

Column materials: Silica gel 60, 40–63 μm, Merck 1.09385.2500; Sephadex LH-20, Pharmacia Biotech, Nr. 17-0090-02; Optical rotation: Perkin-Elmer 341 polarimeter; NMR: 1- and 2-D measured at a Bruker UltraShield 600 MHz; using acetone-d6 (Euriso-Top, Saint-Aubin, France); Mass spectrometry: Bruker Esquire 3000plus iontrap (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany); LC–MS: LC-parameters for isolation of lignans and LC–MS measurement: 1100 Agilent system, equipped with column oven, photodiode array detector and auto sampler; stationary phase: Max RP 80 A column (150 × 4.6 mm, 3.5 μm particle size, Phenomenex); mobile phase: water bidest. (A) and methanol (B); flow rate: 1.0 ml/min; detection wavelength: 221 nm; composition: start 74% A, 26% B; 40 min 50% A, 50% B; 42 min 2% A, 98% B; stop 47 min; post time 10 min, oven temperature: 40 °C. MS-parameters: ESI (in alternating mode): LC flow spitted 1:5; spray voltage 4.5 kV; nebulizer: He, 30 psi, dry gas: N2, 10 l/min; 350 °C; scanning range: 100–1500 m/z. LOBAR: Perkin-Elmer, Series 3 Liquid Chromatograph connected to an Agilent HP UV detector series 1100 (Böblingen, Germany) set to 221 nm; LOBAR® column, size A (240 × 10 mm) LiChroprep RP-18, 40–63 μm (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

In vitro experiments with freshly isolated human PBMC

PBMC were isolated from whole blood of healthy voluntary donors by density centrifugation as described (Jenny et al. 2011). These cells were washed three times in phosphate buffered saline containing 1 μM EDTA. After that, cells were kept in RPMI 1640 enriched with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 2 mM glutamine (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) and 0.1% gentamicin (50 mg/ml, Bio-Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) in a moisturized atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 h. For incubation, the isolated cells were plated in supplemented culture medium RPMI 1640 at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml.

The lyophilized methanol and ethylacetate seed extracts were dissolved in ethanol and tested in unstimulated and stimulated PBMC for an influence on tryptophan breakdown and neopterin production. Because lignans trachelogenin, arctigenin and matairesinol were considered to be of major relevance for the observed effects of these extracts, in a next step, three stock solutions of each of the three compounds were prepared in DMSO being equivalent to 644 μM, 602 μM, and 782 μM. Four dilutions in culture medium were applied at the PBMC: 1:100, 1:50, 1:10 and 1:4. 1-methyl-d-tryptophan (D-1MT) (Sigma–Aldrich, 95% purity) was used as a positive control for inhibition of IDO. After 30 min of preincubation with compounds, PBMC were stimulated or not with 10 μg/ml of mitogen PHA. After incubation for 48 h, cell viability was measured by CellTiterBlue assay (Promega, Germany) while the supernatants were gained by centrifugation. All experiments were run in triplicates with minimum of two parallels.

Tryptophan breakdown and neopterin formation were assayed in unstimulated PBMC as well in cells triggered by stimulation with 10 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), a mitogen which preferentially activates IFN-γ releasing Th1-type lymphocytes (Weiss et al. 1999).

HPLC determinations of tryptophan and kynurenine concentrations in supernatants

The extent of tryptophan breakdown estimating the activity of IDO was calculated as the ratio of the concentrations of kynurenine and tryptophan (KYN/TRP) (Fuchs et al. 1990), which were measured by HPLC (Widner et al. 1997). The HPLC system consisted of a Prostar 210 solvent delivery system (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). Sample injection was controlled by a Prostar 400 autosampler configured for 96 samples. Separation was accomplished at room temperature using a reverse-phase LiChroCART 55-4 cartridge (Merck), 55 mm in length, filled with Purosphere STAR RP18 (3 μm grain size, Merck) together with a reverse-phase C18 pre-column (Merck). Mobile phase was 15 mM KH2PO4. Analytes were eluted at a flow rate of 0.9 ml/min. Injection volume was 30 μl. Tryptophan concentrations were detected by a Varian Prostar fluorescence detector (ProStar 360) at 210 nm excitation and 302 nm emission wavelengths. Concentrations of kynurenine and of the internal standard 3-nitro-l-tyrosine were detected by a ultraviolet detector (ProStar 325) at 360 nm wavelength. One single chromatographic run was completed within 7 min. Concentrations of compounds were calculated according to peak heights. For peak quantification, Prostar and MicroSoft Excel software were used.

In parallel, neopterin production in culture supernatants was measured by a commercially available competitive enzyme immunoassay (BRAHMS Diagnostica, Hennigsdorf, Germany) following the instructions of the manufacturer. The wells of the microtitre plate are coated with polyclonal sheep anti-neopterin antibodies. After addition of the enzyme neopterin/alkaline phosphatase conjugate to standards, the neopterin of specimens competes with the neopterin/enzyme conjugate for the binding sites of these antibodies, thus forming an immune complex bound to the solid phase. Upon addition of the 4-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate solution the enzyme reaction starts and develops yellow 4-nitrophenol which is measured at an absorption wavelength of 405 nm. The enzymatic reaction is stopped by alkalinization with sodium hydroxide. The results are calculated by plotting against a standard curve.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as percent of unstimulated and PHA-stimulated control and were shown as means ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values) were calculated according to Chou and Talalay (1984). Comparison of Emax values was done with ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test. Other group comparisons were performed using non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis-, Mann–Whitney-test for comparisons of groups and Spearman rank test for regression analyses), because not all the data sets showed normal distribution; p-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. For statistical evaluation of the data, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS 15.0 was used.

Results

Effect of PBMC stimulation

As compared with resting cells, the stimulation of PBMC with PHA led to a significant increase of tryptophan breakdown (KYN/TRP: 54.1 ± 13.6 μmol/mmol in unstimulated vs. 3852 ± 1092 in stimulated PBMC; p < 0.05) manifested in the decline of tryptophan (25.2 ± 2.5 μmol/l in unstimulated vs. 4.6 ± 0.68 in stimulated PBMC; p < 0.05) and a concomitant increase of kynurenine concentrations (1.21 ± 0.20 μmol/l in unstimulated vs. 14.5 ± 2.5 in stimulated PBMC; p < 0.05). In parallel, neopterin production increased (11.2 ± 2.6 nmol/l in stimulated vs. unstimulated PBMC (4.3 ± 1.4 nmol/l; p < 0.05).

Influence of seeds extracts and of test compounds

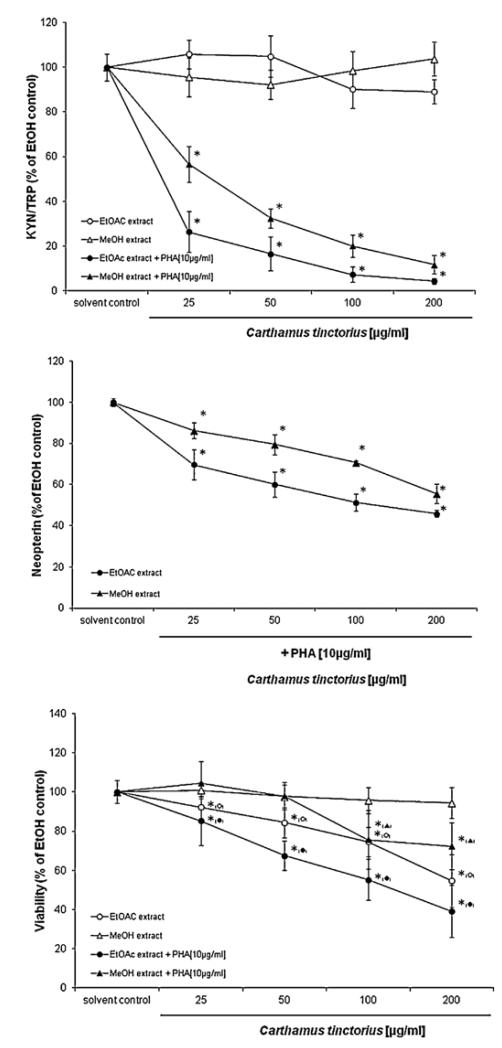

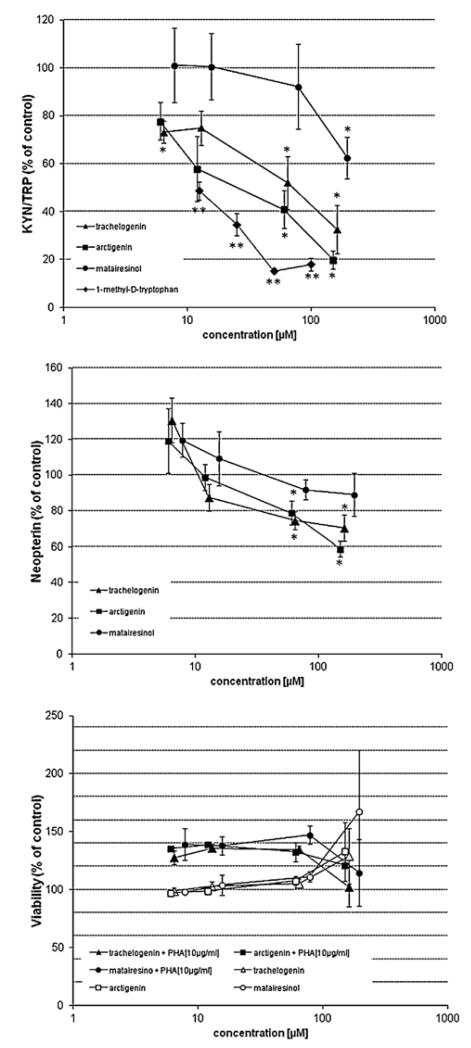

Methanol and ethylacetate seed extracts exerted a concentration-dependent influence on tryptophan breakdown in PBMC stimulated with PHA (Fig. 2). There were also suppressive effects on neopterin production but they were less marked as compared with KYN/TRP. There was no such influence on unstimulated cells. At the higher concentrations of extracts, cell viability declined and this was especially true for the ethylacetate extract. However, the influence on tryptophan breakdown was much stronger, and so we decided to continue with further investigations of isolated lignans. The compounds trachelogenin, and arctigenin concentration-dependently reduced tryptophan breakdown and decreased kynurenine production. As a consequence, KYN/TRP declined as compared with the PHA-stimulated PBMC without added compounds (Fig. 3). Arctigenin showed the highest activity with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50 value) of 26.5 μM (95% confidence interval: 18.2–38.7 μM), followed by trachelogenin (IC50 = 57.4 μM; 95% confidence interval: 33.2–101 μM). Matairesinol showed only weak suppressive effects, decreasing KYN/TRP significantly only at a concentration of 193 μM but still 50% suppression was not observed with this concentration (Fig. 3). At the highest concentrations tested the suppression of tryptophan breakdown was significantly stronger for arctigenin (t = 4.537, p < 0.01) and trachelogenin (t = 3.616, p < 0.02) as compared with maitaresinol. There was no significant difference between the effects of arctigenin and trachelogenin. IC50 concentration of arctigenin was only approximately 2.5-fold higher than that of the classical IDO inhibitor D-1MT with an IC50 of 9.3 μM (confidence interval: 4.3–20.2 μM) which served as a positive control. As the seed extracts, also the pure compounds had no significant effects on tryptophan breakdown in unstimulated cells (details not shown).

Fig. 2.

Concentration-dependent influence of the methanol and ethylacetate extracts of Carthamus tinctorius seeds on tryptophan breakdown indicated by the kynurenine to tryptophan ratio (KYN/TRP; upper graph), on neopterin production (middle graph) and on cell viability (lower graph) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with 10 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA). Shown data represent the mean of three independent double experiments ± S.E.M. in percent of control.*p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 (Kruskal–Wallis- and Mann–Whitney-test).

Fig. 3.

Effect of Carthamus tinctorius compounds trachelogenin (▲), arctigenin (■), and matairesinol (●), and the positive control 1-methyl-d-tryptophan (◆) on the kynurenine to tryptophan ratio (KYN/TRP; upper graph), on neopterin production (middle graph) and on cell viability (lower graph) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin. Shown data represent the mean of three independent double experiments ± S.E.M. in percent of control (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; Kruskal–Wallis- and Mann–Whitney-test).

The influence of lignans on neopterin-production rates of stimulated cells was less impressive and it was only affected at the two higher concentrations of trachelogenin and arctigenin (Fig. 3). A slight but not significant stimulation of neopterin production and IDO activity was observed at lower concentrations of compounds trachelogenin and arctigenin (details not shown). Neopterin production rates and KYN/TRP correlated significantly when concentrations in supernatants of each experiment were compared (trachelogenin: rs = 0.686, p < 0.001; arctigenin: rs = 0.658, p < 0.001; matairesinol: rs = 0.541, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our study shows that the methanol and the ethylacetate extracts of C. tinctorius suppress the mitogen-induced tryptophan breakdown (kynurenine to tryptophan breakdown; KYN/TRP) in a concentration-dependent way. The methanol extract contains the lowest concentration of lignans (approximately 0.05%). The ethylacetate extraction achieved an enrichment of lignans to approx. 0.2%. The in vitro testing revealed a somewhat stronger suppressive effect of the ethylacetate extract as compared with the methanol extract and thus would agree with the higher content of lignans in this extract (Fig. 2). Although cell viability was affected especially with the ethylacetate extracts, the influence of the extracts on KYN/TRP was much stronger and could be observed already at lower concentrations where viability still was above 80% of baseline (Fig. 2). Notably, the vehicle in all cell culture experiments was always ethanol, when the primary solvent for the extraction procedure was lyophilized (see Methods section). Subsequent experiments show that C. tinctorius compounds trachelogenin and arctigenin suppress the mitogen-induced tryptophan breakdown in a concentration-dependent way, and there was no influence of compounds on cell viability. Matairesinol was only suppressive at the highest concentration. Data imply that the tested lignans at least partly contribute to the effects observed with the crude extracts. In parallel, to KYN/TRP, C. tinctorius compounds suppressed neopterin production of stimulated PBMC. Results are comparable to earlier studies when plant extracts and alkaloids were found to have a similar effect on tryptophan breakdown and neopterin production. Arctigenin at 26.5 μM and trachelogenin at 57.4 μM concentrations suppressed mitogen-induced KYN/TRP by 50%, whereas 200 μM of matairesinol was needed for a comparable effect. Significant correlations were observed between neopterin concentrations and KYN/TRP in the culture supernatants. Results suggest an influence of compounds on cytokine cascades which are elicited by the mitogen PHA and are involved in the induction of IDO with the breakdown of tryptophan as well as the formation of neopterin. Because, neopterin production and tryptophan breakdown in PHA stimulated PBMC is mainly due to the effects of IFN-γ released from activated T-cells, data suggest that the major influence of the lignans is the suppression of T-cell activation cascades including IFN-γ formation.

Interestingly, the activity of maitaresinol in the in vitro assay was different from trachelogenin and arctigenin (Fig. 3), though the chemical structures of all three compounds are closely related. Matairesinol, which differs from arctigenin by the substitution of one methoxy group by a hydroxyl group, had a significant effect only at the highest concentration tested. Such results suggest that there might be a more direct effect of the other two compounds on IDO activity, which could be in addition to their immunomodulatory property. Still, there is no obvious structural similarity between arctigenin and tryptophan or D-1MT which could explain this effect. Neopterin production and tryptophan breakdown were demonstrated earlier in the myelomonocytic cell line THP-1 to correlate closely with induction of NF-κB (Schroecksnadel et al. 2010). One can conclude that the similar effects of all three compounds on neopterin production and tryptophan breakdown are typical for a suppression of T-cell/macrophage activation cascades in the PBMC. Certainly further studies are needed to clarify this point.

Effective concentrations of trachelogenin and arctigenin with IC50 in the 10–50 μM range compare well with other earlier tested compounds in the same PBMC assay system, e.g., significant suppression of tryptophan breakdown and neopterin production was observed for the stilbene derivative resveratrol and the cannabinoids Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol at concentrations >10 μM (resveratrol) and 1 μg/ml (cannabinoids) respectively (Wirleitner et al. 2005; Jenny et al. 2009). Similar inhibition was observed also for alkaloid compounds of Uncaria tomentosa (Winkler et al. 2004b) and for extracts of Hypericum perforatum (Winkler et al. 2004a). The seeds of Carthamus tinctorius contain only small quantities of the active lignan-derivatives, e.g., 3.7–6.6 mg% matairesinol and 14.3–21.7 mg% trachelogenin, the content of the corresponding glycosides was found to be 5 to 10 times higher (Kim et al. 2007). Interestingly, it was recently shown that tracheloside can be converted by fecal bacterial mixture of rats to the corresponding aglycon (Jin et al. 2012) and might be therefore still bioavailable after oral intake of a safflower preparation. Particularly in the gut the concentrations of the active compounds can reach high enough concentrations to influence cell metabolism and modulate cytokine profiles in cells of the gastrointestinal tract.

In earlier studies applying the same PBMC assay, the antioxidant character of compounds was found to be an important feature for their anti-inflammatory properties (Jenny et al. 2011). This could be also of some relevance for the findings in this study, although it is unclear how the introduction of hydroxyl groups (R1 or R2; Fig. 1) might influence the redox properties of the compounds. Still results would be plausible when any antioxidant character of compounds neutralizes reactive oxygen species which play an important role in the forward-regulation of Th1-type immune response (Jenny et al. 2011), and it is well establishes that reactive oxygen species drive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Naik and Dixit 2011).

As tryptophan breakdown was found to be enhanced in patients suffering from chronic inflammatory disease such as HIV-1 infections or colorectal cancer and during interferon-α therapy and has been demonstrated to relate to neuropsychiatric disturbances (Schroecksnadel et al. 2006; Haroon et al. 2012), the applications of safflower in Traditional Chinese Medicine to alleviate pain and increase circulation (von Bruchhausen 2007; Pharmacopoeia of PRC 2010) could relate to the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory capacity of compounds and especially on the tryptophan metabolism found in this study. Trachelogenin and arctigenin might be useful immunomodulators for, e.g., adjuvant cancer therapy and might improve the course of neurological disorders. At least it seems plausible that the lignans trachelogenin and acrtigenin could be responsible for most if not all the anti-inflammatory activity of C. tinctorius extracts in our test system.

In summary, in a pilot experiment with the crude methanolic extract of C. tinctorius we observed significant effects on immunobiochemical pathways which were most impressive in a dose-dependent suppression of IDO activity. In a next step we decided to isolate three major lignans. Thereby it was of particular interest to note that they were as well dose-dependently suppressive but effects were quite distinct although structurally very similar. From the data we conclude that two lignans, namely trachelogenin and arctigenin exert a dominant influence on PBMC that could explain the effects seen with the whole extracts although synergism might exist. Other plant lignans may possess similar properties but this is the first study in which we investigated the effects of such compounds. Therefore, we cannot extrapolate but would assume that there will be other plant lignans with comparable effects.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the TWF (“Tiroler Zukunftsstiftung”), the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science and Research, the Federal Ministry of Health (Sino-Austrian TCM project) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; DNTI S10703, S10711 and 25150-B13).

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bae SJ, Shim SM, Park YJ, Lee JY, Chang EJ, Choi SW. Cytotoxicity of phenolic compounds isolated from seeds of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) on cancer cell lines. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2002;11:140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Boldizsar I, Kraszni M, Toth F, Noszal B, Molnar-Perl I. Complementary fragmentation pattern analysis by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry confirmed the precious lignan content of Cirsium weeds. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217:6281–6289. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bruchhausen F. Carthamus tinctorius L. In: Blaschek W, Ebel S, Hack-enthal E, Holzgrabe U, Keller K, Reichling J, Schulz V, editors. Hagers Enzyklopädie der Arzneistoffe und Drogen (4) 6th ed vol. 3. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; Stuttgart: 2007. pp. 880–883. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne GI, Lehmann LK, Kirschbaum JG, Borden EC, Lee CM, Brown RR. Induction of tryptophan degradation in vitro and in vivo, a gamma-interferon-stimulated activity. Journal of Interferon Research. 1986;6:389–396. doi: 10.1089/jir.1986.6.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Liang X, Peterson AJ, Munn DH, Blazar BR. The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathway is essential for human plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced adaptive t regulatory cell generation. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:5396–5404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Guillemin GJ. Kynurenine pathway metabolites in humans, disease and healthy states. International Journal of Tryptophan Research. 2009;2:1–19. doi: 10.4137/ijtr.s2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose–effect relationships, the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Pharmacopeia. 6. ed. 4. addendum. Verlag Österreich GmbH; Wien: 2008. p. 6211. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J, Reynolds AJ, Sharp LA, Sherburn MS. Radical carboxyarylation approach to lignans. Total synthesis of (−)-arctigenin, (−)-matairesinol, and related natural products. Organic Letters. 2004;6:1345–1348. doi: 10.1021/ol049878b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Möller AA, Reibnegger G, Stöckle E, Werner ER, Wachter H. Decreased serum tryptophan in patients with HIV-1 infection correlates with increased serum neopterin and with neurologic/psychiatric symptoms. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1990;3:873–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon E, Raison CL, Miller AH. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology, translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:137–162. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny M, Santer E, Pirich E, Schennach H, Fuchs D. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol modulate mitogen-induced tryptophan degradation and neopterin formation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2009;207:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny M, Klieber M, Zaknun D, Schroecksnadel S, Kurz K, Ledochowski M, Schennach H, Fuchs D. In vitro testing for anti-inflammatory properties of compounds employing peripheral blood mononuclear cells freshly isolated from healthy donors. Inflammation Research. 2011;60:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00011-010-0244-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JS, Tobo T, Chung MH, Ma CM, Hattori M. Transformation of trachelogenin, an aglycone of tracheloside from safflower seeds, to phytoestrogenic (−)-enterolactone by human intestinal bacteria. Food Chemistry. 2012;134:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim EO, Oh JH, Lee SK, Lee JY, Choi SW. Antioxidant properties and quantification of phenolic compounds from safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) seeds. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2007;16:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Muller AJ, DuHadaway JB, Donover PS, Sutanto-Ward E, Prendergast GC. Inhibition of indoleamie 2,3-dioxygenase, an immunoregulatory target of the cancer supression gene Bin 1, potentiates cancer chemotherapy. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:312–319. doi: 10.1038/nm1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik E, Dixit VM. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species drive proinflammatory cytokine production. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011;208:417–420. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Cui L, editors. Pharmacopoeia of Peoples’ Republic of China. English ed vol. 1. China Medical Science and Technology Press; Beijing: 2010. pp. 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schröcksnadel K, Wirleitner B, Winkler C, Fuchs D. Monitoring tryptophan metabolism in chronic immune activation. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2006;364:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroöksnadel S, Jenny M, Kurz K, Klein A, Ledochowski M, Ueberall F, Fuchs D. LPS-induced NF-kappaB expression in THP-1Blue cells correlates with neopterin production and activity of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;399:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman H, Mediavilla-Varela M, Antonia S. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: is it an immune supressor? Cancer Journal. 2010;16:354–359. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eb3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone TW. Kynurenines in the CNS, from endogenous obscurity to therapeutic importance. Progress in Neurobiology. 2001;64:185–218. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takikawa O. Biochemical and medical aspects of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-initiated l-tryptophan metabolism. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;338:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G, Murr C, Zoller H, Haun M, Widner B, Ludescher C, Fuchs D. Modulation of neopterin formation and tryptophan degradation by Th1-and Th2-derived cytokines in human monocytic cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1999;116:435–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widner B, Werner ER, Schennach H, Wachter H, Fuchs D. Simultaneous measurement of serum tryptophan and kynurenine by HPLC. Clinical Chemistry. 1997;43:2424–2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C, Wirleitner B, Schroecksnadel K, Schennach H, Fuchs D. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) counteracts cytokine-induced tryptophan catabolism in vitro. Biological Chemistry. 2004a;385:1197–1202. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C, Wirleitner B, Schroecksnadel K, Schennach H, Mur E, Fuchs D. In vitro effects of two extracts and two pure alkaloid preparations of Uncaria tomentosa on peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Planta Medica. 2004b;70:205–210. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirleitner B, Schroecksnadel K, Winkler C, Schennach H, Fuchs D. Resveratrol suppresses interferon-gamma-induced biochemical pathways in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Immunology Letters. 2005;100:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Gai Y, Chu WJ, Qin GW, Guo LH. A novel compound N(1) N(5)-(Z)-N(10)-(E)-tri-p-coumaroylspermidine isolated from Carthamus tinctorius L. and acting by serotonin transporter inhibition. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19:749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]