Abstract

Background and Purpose

Elevation of intracellular calcium was traditionally thought to be detrimental in stroke pathology. However, clinical trials testing treatments which block calcium signaling have failed to improve outcomes in ischemic stroke. Emerging data suggest that calcium may also trigger endogenous protective pathways following stroke. CaMKK (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase) is a major kinase activated by rising intracellular calcium. Compelling evidence has suggested that CaMKK and its downstream kinase CaMK IV are critical in neuronal survival when cells are under ischemic stress. We examined the functional role of CaMKK/CaMK IV signaling in stroke.

Methods

We utilized middle cerebral artery occlusion model in mice.

Results

Our data demonstrated that pharmacological and genetic inhibition of CaMKK aggravated stroke injury. Additionally, deletion of CaMKK β, one of the two CaMKK isoforms, reduced CaMK IV activation and CaMK IV deletion in mice worsened stroke outcome. Finally, CaMKK β or CaMK IV KO mice had exacerbated BBB (blood brain barrier) disruption evidenced by increased hemorrhagic transformation rates and activation of matrix metalloproteinase. We observed transcriptional inactivation including reduced levels of BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) and HDAC4 (histone deacetylase 4) phosphorylation in those KO mice after stroke.

Conclusions

Our data has established that the CaMKK/CaMK IV pathway is a key endogenous protective mechanism in ischemia. Our results suggest that this pathway serves as important regulator of BBB integrity and transcriptional activation of neuroprotective molecules in stroke.

Keywords: Cerebral ischemia, CaMKK β, CaMK IV

Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of disability worldwide.1 Calcium signaling plays a critical role in the pathology of cerebral ischemia.2 Limits in the available blood supply lead to energy depletion and uncontrolled release of glutamate, exacerbated by impaired reuptake, and ultimately leads to increased calcium influx through the hyperactivation of the NMDA receptor.3 Increased neuronal free calcium activates numerous molecules which can participate in signal transduction pathways leading to cell survival and/or cell death.4 Many of these secondary effects of Ca2+ are mediated through the ubiquitous Ca2+ sensing protein, calmodulin (CaM). Calcium overload was traditionally believed to be detrimental in stroke.2 However clinical trials testing treatments that block calcium failed to show neuroprotection in ischemic stroke. One possible explanation is that those approaches non-specifically targeted calcium signaling. It has become increasingly recognized that enhancing calcium signaling may also play an important protective role after injury by triggering endogenous neuroprotective pathways. 5

A critical upstream kinase directly activated by calcium/calmodulin signaling is CaMKK, a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase. This kinase has two isoforms α and β, both of which are expressed in the nervous system and hematopoietic cells.6 A very early study implicated CaMKK in neuronal cell survival pathways. In this study, CaMKK-mediated phosphorylation of Akt protected neurons from apoptosis induced by serum withdrawal in neuroblastoma cells.7 Once activated, CaMKK phosphorylates its two main downstream targets, CaMK I and CaMK IV. CaMK IV is expressed primarily in cells of nervous system, the hematopoietic system, and the gonads. CaMK IV resides in both the nucleus and cytosol but the active form of CaMK IV (phosphorylated) is predominantly nuclear, due to facilitated transportation by importin α.8 Once CaMK IV is phosphorylated, it enhances the pro-survival B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (BCL-2) gene via actions on CREB.10 CaMK IV also actively regulats gene transcription by phosphorylating HDAC4 (histone deacetylase 4). When neurons are under stress, HDAC4 translocates from cytosol into nucleus, then represses the expression survival gene such as MEF2a (myocyte specific enhancer factor 2). Phosphorylation of HDAC4 by CaMK IV promotes HDAC4 nuclear exports in neurons, resulting in neuroprotection in excitotoxic glutamate condition,9 a major cell death mechanism in cerebral ischemia. Therefore, CaMKK and its downstream pathways may be endogenous neuroprotective mechanisms in stroke. In the present study, we investigated the role of CaMKK signaling in stroke and its downstream mediators in the ischemic brain.

Methods

Animals

The present study was conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of animals in research and under protocols approved by the Center for Laboratory Animal Care of University of Connecticut Health Center. Both CaMKK β KO mice and CaMK IV knockout mice were provided by Dr. Anthony Means at Duke University and were backcrossed to C57BL/6J background.10 Control mice for both null lines were generated from F1 heterozygous mattings and backcrossed to C57BL/6J backgrounds.10 All studies used male animals age- and weight-matched (21 to 25 g, 10 to 12 weeks of age).

Middle cerebral artery occlusion

Focal transient cerebral ischemia (90 min MCA occlusion) was induced in WT, CaMKK β KO or CaMK IV KO mice followed by reperfusion as described previously.11 At the end of ischemia, the animal was briefly re-anesthetized, and reperfusion was initiated by filament withdrawal. During the ischemic period, animal body temperatures were controlled at 37 °C using a heating pad with feedback thermo-control system (FST). In separate cohorts of CaMK IV KO and WT animals, as well as the STO-609 (an inhibitor of CaMKK)/vehicle treated animals (n=4 p/g), physiological measurements including femoral arterial blood pressure, pH, pO2, pCO2, and blood glucose, were obtained. In those separate cohorts, cortical perfusion using Laser Doppler Flowmetry was evaluated throughout MCAO and early reperfusion as described previously.11 Animals were randomized into stroke and surgical sham cohorts. Investigators who performed the procedures were blinded to drug treatment and genotype.

Drug treatment

STO-609, a pan CaMKK inhibitor (2 μl, 1.5mg/ml, dissolved in DMSO) was injected intracerebroventricularly (icv) to male WT mice at the coordinates (From bregma; −0.9 mm lateral, −0.1 mm posterior, −3.1 mm deep) 30 mins prior to the onset of MCAO. Control animals were injected with equal amount of vehicle (DMSO).

Methods for Infarct measurement11/Edema formation12/Behavior measurement11/Subcellular fractionation13/Western blots13/Gelatinase activity assay14/Statistics analysis

Please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org and refer to supplemental materials for methods.

Results

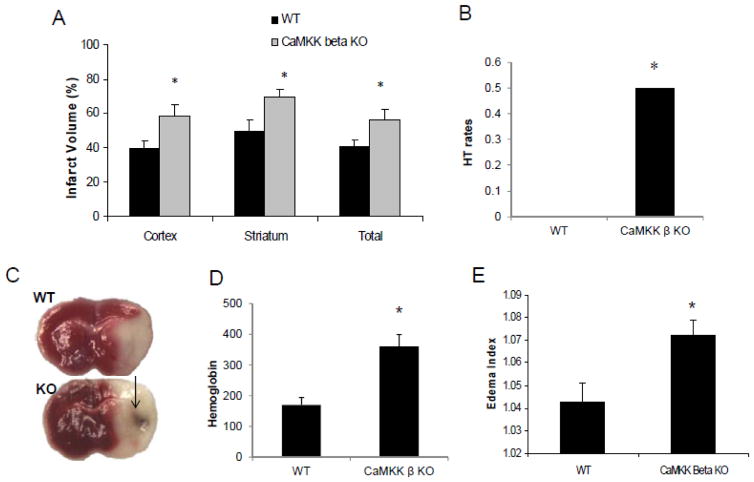

Genetic deletion of CaMKK β aggravated stroke infarction, hemorrhagic transformation and edema

Infarct volumes (percentage of contralateral structure) were significantly higher in CaMKK β knockout mice compared to WT controls 24 hours after stroke (cortex: KO 58.0±7.1% versus WT 39.5±4.0% p=0.036, striatum: KO 69.6±3.9% versus WT 49.0±6.8% p=0.016, total: KO 56±5.7% versus WT 40.6±3.8% p=0.039, n=7 WT/8 KO/pg) (Figure 1A & B). Interestingly, we observed increased rates of hemorrhagic transformation in CaMKK β KO mice after stroke. Macroscopic hemorrhagic transformation was visually identified in brains after TTC staining (Figure 1B). Higher HT rates were seen in CaMKK β KO mice (KO 50% versus WT 0%, n=7–8 p/g, p=0.029).

Figure 1. CaMKK β KO mice had larger infarcts and greater edema formation than the WT control.

A. CaMKK β gene deletion increased infarct volume assessed 24 hours after stroke. Cortical, striatal and total hemisphere infarction volumes were calculated (percentage of non-ischemic hemisphere). n=7 WT group, n=8 KO group; arrow: HT. B. representative TTC stained brain slices from WT control and CaMKK β KO mice. C. Exacerbated edema formation was observed in CaMKK β KO mice after stroke. n=6 p/g. The tissue water content was calculated as % H2O = (1 − dry wt/wet wt) × 100%. *p < 0.05 vs. control (Student’s t-test); Data were presented as Mean±Sem.

We measured edema formation at 24 hours after stroke using wet/dry weights then calculated the edema index. CaMKK β mice had significantly higher edema formation than WT control (1.0722 ± 0.0068 versus 1.0426±0.0084, p=0.021 n =6 p/g) (Figure 1C).

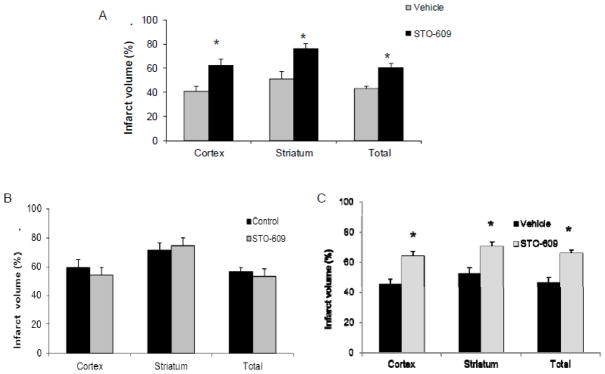

Pharmacological CaMKK inhibition with STO-609 exacerbated stroke infarct size

To confirm the effects of the detrimental effects of CaMKK genetic inhibition, we treated mice with the pharmacological CaMKK inhibitor STO-609. Treatment of WT mice with STO-609 (i.c.v) exacerbated stroke outcome when compared to vehicle treatment 24 hours after stroke (cortex: drug 61.9± 5.9% versus vehicle 40.8 ± 4.2% p=0.014, striatum: drug 75.9 ±4.2% versus vehicle 51.2±4.2% p=0.046, total: drug 59.9± 4.2% versus vehicle 42.9±1.9 % p=0.047, n=8–9/pg) (Figure 2A). There were no differences in mean arterial pressure, pO2, pCO2, or pH between the STO-609-treated and vehicle-treated groups. In addition, local cerebral blood flow as measured by Laser Doppler Flow was equivalently reduced during ischemia (drug 13.3±1.0% versus vehicle 12.8±1.2%, n=4/pg) and was restored equally in early reperfusion (drug 86.9 ±4.8% versus vehicle 83.1±5.1%, n=4/pg) (ST1).

Figure 2. STO-609 increased the stroke infarct volumes in WT mice.

A. STO-609 treatment exacerbated stroke injury in WT mice assessed 24 hours after stroke. CaMKK inhibitor was injected introcerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) to male WT mice 30 mins prior to the onset of MCAO. Control animals received the equal amount of vehicle. Cortical, striatal and total hemisphere infarction volumes were calculated (percentage of non-ischemic hemisphere). n= 8 vehicle group, n=9 STO-609 treated group. B. CaMKK pan-inhibitor STO-609 did not change the stroke outcome in CaMKK β KO mice after 90-min MCAO. n=5p/g. STO-609/vehicle were injected to CaMKK β KO mice. *p < 0.05 vs. control (Student’s t-test); Data were presented as Mean±Sem.

To verify the mechanism and specificity of STO-609, we administered STO-609 (i.c.v.) to CaMKK β KO mice prior to stroke. STO-609 had no effect on infarct size in CaMKK β KO mice (Cortical STO 54.2±5.1 versus 59.4 ±5.6, Striatum STO-609 74.5±5.5 versus control 71.6±4.8, Total 53.4±5.0 versus control 56.9±2.7, n=5 p/g) (Figure 2B), suggesting that STO609 conferred its deleterious effects in stroke at least in part through CaMKK β inhibition.

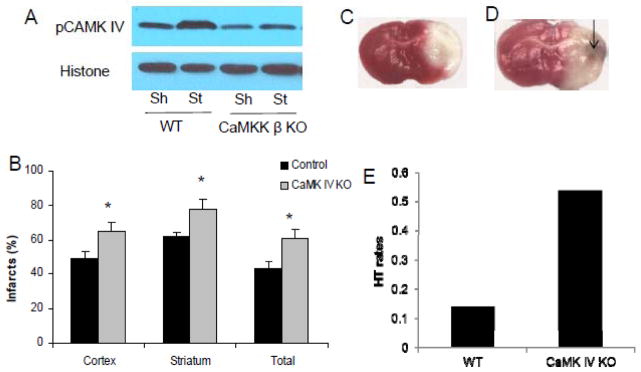

CaMKK β deletion reduced nuclear pCaMK IV levels after stroke

To determine mechanisms behind the increased ischemic damage in CaMKK β KO mice after stroke, we then examined CaMK IV, a major downstream molecule activated by CaMKK β. As active CAMK IV (pCaMK IV) presents in the nucleus, we examined nuclear pCaMK IV levels. pCaMK IV levels increased in WT mice after stroke, however, CaMKK deletion reduced pCaMK IV levels in the nucleus after stroke (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. CaMK IV genetic deletion is detrimental in stroke.

A. CaMKK β deletion reduced nuclear pCaMK IV levels in mice after stroke 6 hours after the onset of ischemia. Sh, sham; St: stroke. Each band represents two mice brains (pooled for nuclear subcellular fractionation). B, C and D: CaMK IV gene deletion increased infarct volume after stroke. Arrow: HT; CaMK IV KO and WT control mice were subject to 90 min MCAO. Cortical, striatal and total hemisphere infarction volumes (24 hours after stroke) were calculated (percentage of non-ischemic hemisphere). *p < 0.05 vs. control (Student’s t-test); Data were presented as Mean±Sem. n=7 per group.

CaMK IV KO mice had larger infarcts than WT mice

To determine if CaMK IV plays protective roles in stroke, we investigated effect of genetic deletion of CaMK IV in mice in stroke. CaMK IV genetic deletion significantly increased infarct volumes in cortical (KO 64.9 ± 4.9% vs. WT 48.9±4.1%, p=0.029), striatal (KO 77.8±5.8% vs. WT 62.2±2.5%, p=0.032) and total (KO 61.0±5.1% vs. WT 43.4±3.7%, p=0.018) (n=7/pg) compared to WT controls 24 hours after stroke (Figure 3B,C,D). This detrimental effect was reflected in the exacerbated neurological deficits of the KO mice (KO 3.1±0.3 vs. WT 2.3±0.2, p=0.041). Stroke-induced mortality was seen in 6 out of 13 in CaMK IV KO mice whereas no mortality was seen in the WT controls (p=0.031). Macroscopic cerebral hemorrhagic transformation was visually identified in brains after TTC staining or with post mortem inspection in mice that died prematurely after stroke. There is a trend towards statistical significance in HT rates in CaMK IV KO mice when compared to WT controls (KO 53.8% versus WT 14.2%, n=13 in KO, n=7 in WT, p=0.09).

There were no differences in mean arterial pressure, pO2, pCO2, or pH between CaMK IV KO and WT groups. In addition, local cerebral blood flow as measured by Laser Doppler Flow was equivalently reduced during ischemia (KO 11.2±1.1% versus WT 12.3±1.1%, n=4/pg) and was restored equally in early reperfusion (KO 77.5 ± 1.0% vs. vehicle 83.4±2.0%, n=4/pg) (ST1, please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org).

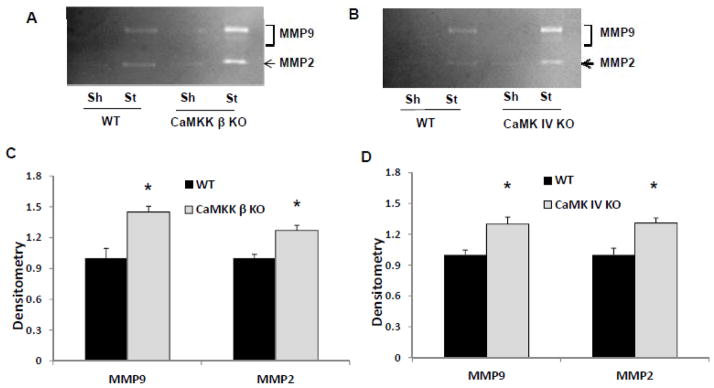

Gelantinase activity increased in both CaMKK β KO and CaMK IV KO mice 6 hours after stroke

To determine the mechanism underlying the increased HT rates seen in both the CAMMK strains ask why KOs had increased HT rates, we examined the activity of MMPs following stroke. MMPs are known to cleave BBB proteins and responsible for BBB disruption following stroke. CaMKK β deletion significantly enhanced MMP-9 and MMP-2 activity 6 hours after stroke when compared to WT controls (Figure 4A&C, n=3 per stroke group, p=0.042 and 0.029 for MMP-9 and MMP-2 data respectively). Similar results were observed in the CaMK IV KO mice (Figure 4B & D, n=3 per stroke group, p=0.047 and 0.048 for MMP-9 and MMP-2 data respectively).

Figure 4. CaMKK β and CaMK IV gene deletion aggravated gelatinase activity in stroke.

A & B. Representative gelatin zymograpy showing increased MMP 9 and MMP 2 activity in both CaMKK β and CaMK IV KO mice after stroke. CaMK IV KO, CaMKK β KO and their corresponding WT control mice were subject to 90 min MCAO. Six hours after the onset of stroke, mice brains were removed and lysed for zymography. C. Quantification of MMP 9 and MMP 2 activity in the stroke hemispheres by densitometry of gelatin zymography. Data were normalized to corresponding WT control stroke mice in each genotype. *p < 0.05 vs. control (Student’s t-test); Data were presented as Mean±Sem. n=3 stroke per stroke group.

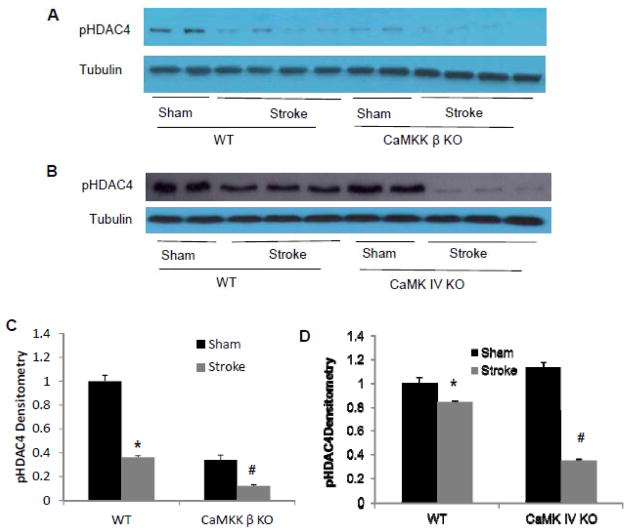

CaMKK β KO and CaMK IV KO mice had reduced pHDAC4 levels

HDAC4 nuclear translocation has been shown to be detrimental for neuronal survival.9 CaMK IV inhibits HDAC4 translocation in neurons under stress via phosphorylation of HDAC4.9 We observed that stroke significantly reduced pHDAC4 levels in WT controls (Figure 5, p=0.000). This reduction was further exacerbated in both CaMKK β KO (p=0.048 KO stroke vs. WT stroke, n=2 in sham, n=4 in stroke) and CaMK IV KO mice (p=0.000 KO stroke vs. WT stroke, n=2 in sham, n=3 in stroke) 6 hours after stroke when compared to WT controls (Figure 5).

Figure 5. CaMKK β KO and CaMK IV KO mice further exacerbated the reduction of pHDAC4 levels 6 hours after stroke.

A&C: CaMKK β deletion reduced pHDAC4 levels in mice. B&D: CaMK IV deletion reduced pHDAC4 levels in mice. Brains were collected 6 hours after onset of MCAO or sham-operation. pHDAC4 levels were assessed with Western blot. Each band represents one mouse brain. * p<0.05: sham vs. stroke; #p<0.05: KO vs. WT (one-way ANOVA).

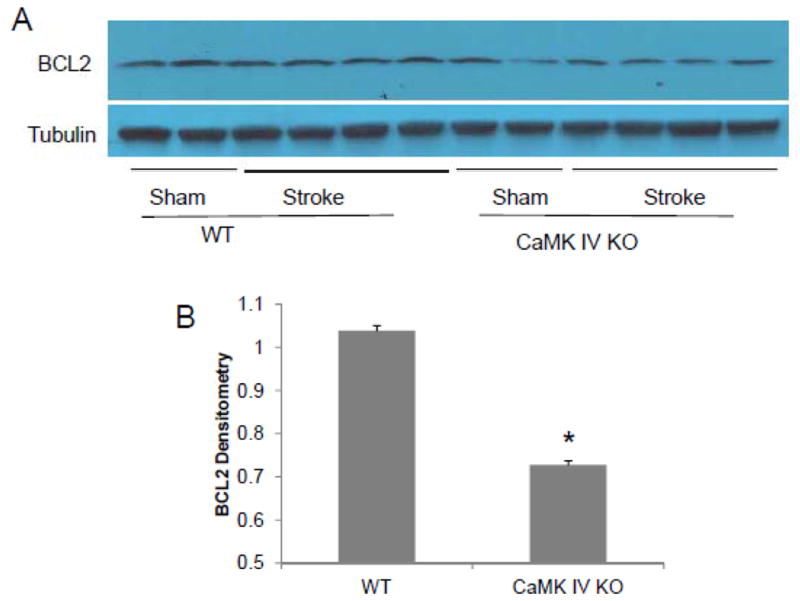

CaMK IV KO mice had reduced BCL2 levels 6 hours after stroke

Expression of BCL2 is regulated by HDAC4 and is neuroprotective in stroke models. We examined BCL2 levels in CaMK IV KO mice. In stroke mice, BCL2 levels were significantly lower in CaMK IV KO mice when compared to WT controls (Figure 6, n=2 in sham, n=4 in stroke, P=0.001 KO stroke vs. WT stroke).

Figure 6. CaMK IV gene deletion reduced BCL2 levels in mice after stroke.

Brains were collected 6 hours after onset of MCAO or sham-operation. A: Actual Western blots; B: Densitometry analysis of the stroke samples using tubulin as controls. BCL2 levels were assessed with Western blot. Each band represents one mouse brain. * p<0.05: KO stroke vs. WT stroke.

CAMKK β inhibition with STO-609 had no effects on pAMPK levels

CaMKK is a known upstream kinase for AMPK,15 a kinase implicated in pathology of stroke.15 We examined the effect of CaMKK inhibition on pAMPK levels 4 hours after stroke. Stroke led to an increase in the levels of pAMPK, however, STO-609 treatment did not change pAMPK levels (SS1, please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org), n=3 p/g) suggesting CaMKK signaling in stroke may be independent of AMPK.

Discussion

This study made the following significant novel findings. First, we found inhibition of CaMKK either pharmacologically or genetically was detrimental in cerebral ischemia and identified CaMKK as a novel biological target for stroke treatment. Second, we showed that CaMKK β deletion reduced phosphorylation of nuclear CaMK IV, a major downstream molecule of CaMKK. In addition, we found that CaMK IV deletion also exacerbated infarct size. Third, loss of either CaMKK β or CaMK IV perturbed BBB integrity after stroke as reflected by a significant increase in edema formation and MMP activation. Fourth, CaMKK/CaMK IV pathway inhibition resulted in transcriptional inactivation as indicated by changes in pHDAC4 and BCL2 levels in KO mice after stroke. Finally, our work demonstrated that inhibition of CaMKK did not affect AMPK phosphorylation, indicating CaMKK operates independently of AMPK signaling in cerebral ischemia.

The exacerbated stroke outcome in CaMKK β KO mice and in STO-609 treated WT mice suggested that CaMKK normally mediates neuroprotective signaling. CaMKK resides in both the cytosol and the nucleus where it responds to changes in Ca2+ levels and signals CaM-kinase. CaMKK is held in an inactive state by its autoinhibitory domain, which interacts with the catalytic domain to prevent kinase activity. Binding of Ca2+/CaM releases this autoinhibitory domain, thus activating the kinase. CaMKK then activates its two primary downstream targets CaMK I and CaMK IV through phosphorylation.8 The neuroprotective actions of CaMKK signaling seen in our study may be mediated in part through CaMK IV as loss of CaMK IV aggravated stroke injury and led to a significant increase in mortality rate. Deletion of CaMK IV led to an exacerbation in stroke injury to a greater degree than CaMKK inhibition, as CaMK IV KO mice had increased mortality rate in addition to significantly larger infarcts. It is likely CaMKK inhibition with selective deletion of the β isoform or STO-609 treatment did not completely block the downstream CaMK IV activity, therefore its effect on stroke outcome was less than the complete loss of CaMK IV. CaMK IV promotes neuronal survival and inhibits apoptosis in cell models possibly through enhancing Creb phosphorylation.19 Loss of CaMKK β or CaMK IV results in decreased CREB phosphorylation (pCREB), a neuronal survival factor, in cerebellar granule cell neurons and reexpression of CaMKK β or CaMKIV in granule cells that lack CaMKK β or CaMK IV, respectively, restores pCREB wild-type levels.10 Over expression of CaMK IV reduced mouse cortical neuronal injury after OGD (oxygen glucose deprivation) in vitro while knockdown CaMK IV aggravated cell injury and the effect of CaMK IV was attributed to subsequent regulation on pCreb.16 The results were consistent with our in vivo study. Chen et al. conducted the first in vivo study to examine the functional role of CaMK IV in brain ischemia and demonstrated that KN-93 (a CaMK inhibitor) enhanced global ischemic injury in rats.17 However, the data has to be interpreted with caution as KN-93 is not a specific CaMK IV inhibitor, but instead a more selective inhibitor of CaMK II,18 which appears to have no direct interaction with CaMKK or CaMK IV.

A novel, but likely critical function of CaMK IV signaling has recently been identified. CaMK IV regulates the function of HDAC4 a newly identified contributor to cell death.9 HDAC4 is usually “trapped” in the cytosol, possibly due to its binding to the 14-3-3 protein family.19 However, active shuttling of HDAC4 between the cytosol and nucleus can be induced. Once in the nucleus, HDAC4 deacetylates histone, making it inaccessible to the transcriptional machinery thus reducing gene transcription.20 Phosphorylation of HDAC4 recruits 14-3-3 protein resulting in nuclear exportation,9 thereby inhibiting its own effects on transcriptional repression. It is hypothesized that HDAC4 represses the transcription of key endogenous survival factors including MEF2a and CREB, which increases transcription of a variety of pro-survival genes, including Bcl-2.21 HDAC4 accumulates in nucleus after toxic glutamate exposure. Interestingly, CaMK IV phosphorylates HDAC4, efficiently exporting this protein from nucleus.9 To the best of our knowledge, we were the first to report a stroke-reduced HDAC4 phosphorylation, indicating a compromise in gene transcription of survival factor under ischemic condition. The HDAC4 phosphorylation reduction was further exacerbated in both CaMKK β KO and CaMK IV KO mice. BCL2, a downstream molecule of HDAC4/Creb was also reduced in CaMK IV KO mice after stroke. Therefore regulating HDAC4 activity may be a mechanism by which CaMK IV contributes to endogenous neuroprotection in stroke.

The CaMKK complex has also been implicated in blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity, a disruption of which is one of the important contributing factors to edema development, brain injury, and hemorrhagic transformation.22 Interestingly, the activation CaMKK inhibits the maturation and retards the differentiation of neutrophils in mouse myeloid cell lines.23 As neutrophils are a major source of MMP-9 in the ischemic brain,24 CaMKK may be an important endogenous protector of the BBB by reducing neutrophil egress and MMPs into the brain parenchyma. Additionally, HDAC inhibition, a capacity which CaMKK/CaMK IV appears to possess, is also thought to be able to inhibit MMPs in ischemia brain via a NF-κB dependent mechanism.25 Therefore inhibition of CaMKK/CaMK IV may exacerbate MMPs activity in stroke. Indeed, in our studies, we found that mice with deletion of the CaMKK β isoform or CaMK IV had greater MMPs activity as early as 6 hours after stroke. Of note, the observed MMPs activity change is more likely being mechanistic than merely being correlating with infarct size as at this early time point stroke is not yet mature. We additionally saw greater degree edema formation in CaMKK β KO mice which is a consequence of BBB breakdown and important contributor to patient mortality.24 We also observed high hemorrhagic transformation rates in mice lacking CaMKK β (statistically significant) or CaMK IV (a trend towards significance). This suggests that CaMKK/CaMK IV signaling may protect the BBB from injury after stroke. Future studies to investigate MMPs, neutrophil activation and egress and CaMKs in stroke are warranted.

We initially thought that loss of CaMKK may reduce stroke injury due to its potential inhibition of AMPK activation, as it is a major upstream activator (via phosphorylation) of AMPK.15 We have previously found that activation of AMPK is deleterious in stroke, and inhibition, either with genetic or pharmacological methods, reduced injury.15 However it appears that loss of CaMKK signaling leads to significant damage, and this is independent of AMPK signaling as stroke-induced activation of AMPK was unchanged in mice treated with STO-609. During ischemia, other AMPK upstream kinases such as LKB115 may function as regulators for AMPK activity.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the detrimental effects of inhibition of CaMKK after stroke. Our data showed that CaMK IV may be an important mediator of CaMKK’s effect in cerebral ischemia. Our work suggests CaMKK/CaMK IV are potential therapeutic targets for stroke treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R01 NS050505 (L.D.M.), R01 NS078446 (J. L.) and American Heart Association grant 09SDG2261435 (J.L.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Judge SI, Smith PJ, Stewart PE, Bever CT., Jr Potassium channel blockers and openers as cns neurologic therapeutic agents. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2007;2:200–228. doi: 10.2174/157488907782411765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horn J, Limburg M. Calcium antagonists for ischemic stroke: A systematic review. Stroke. 2001;32:570–576. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pivovarova NB, Andrews SB. Calcium-dependent mitochondrial function and dysfunction in neurons. Febs J. 277:3622–3636. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tauskela JS, Morley P. On the role of ca2+ in cerebral ischemic preconditioning. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zundorf G, Reiser G. Calcium dysregulation and homeostasis of neural calcium in the molecular mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases provide multiple targets for neuroprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal. 14:1275–1288. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Means AR. The year in basic science: Calmodulin kinase cascades. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2759–2765. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yano S, Tokumitsu H, Soderling TR. Calcium promotes cell survival through cam-k kinase activation of the protein-kinase-b pathway. Nature. 1998;396:584–587. doi: 10.1038/25147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wayman GA, Lee YS, Tokumitsu H, Silva AJ, Soderling TR. Calmodulin-kinases: Modulators of neuronal development and plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:914–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolger TA, Yao TP. Intracellular trafficking of histone deacetylase 4 regulates neuronal cell death. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9544–9553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1826-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokubo M, Nishio M, Ribar TJ, Anderson KA, West AE, Means AR. Bdnf-mediated cerebellar granule cell development is impaired in mice null for camkk2 or camkiv. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8901–8913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0040-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Benashski SE, Venna VR, McCullough LD. Effects of metformin in experimental stroke. Stroke. 41:2645–265. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F, Akella P, Benashski SE, Xu Y, McCullough LD. Expression of na-k-cl cotransporter and edema formation are age dependent after ischemic stroke. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venna VR, Weston G, Benashski SE, Tarabishy S, Liu F, Li J, Conti LH, McCullough LD. Nf-kappab contributes to the detrimental effects of social isolation after experimental stroke. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:425–438. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0990-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Z, Cui J, Brown S, Fridman R, Mobashery S, Strongin AY, Lipton SA. A highly specific inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-9 rescues laminin from proteolysis and neurons from apoptosis in transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6401–6408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1563-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, McCullough LD. Effects of amp-activated protein kinase in cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 30:480–492. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki T, Takemori H, Yagita Y, Terasaki Y, Uebi T, Horike N, Takagi H, Susumu T, Teraoka H, Kusano K, Hatano O, Oyama N, Sugiyama Y, Sakoda S, Kitagawa K. Sik2 is a key regulator for neuronal survival after ischemia via torc1-creb. Neuron. 69:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen SD, Lin TK, Lin JW, Yang DI, Lee SY, Shaw FZ, Liou CW, Chuang YC. Activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase iv and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha signaling pathway protects against neuronal injury and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in the hippocampal ca1 subfield after transient global ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 88:3144–3154. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wayman GA, Tokumitsu H, Davare MA, Soderling TR. Analysis of cam-kinase signaling in cells. Cell Calcium. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Ito A, Kane CD, Liao TS, Bolger TA, Lemrow SM, Means AR, Yao TP. The modular nature of histone deacetylase hdac4 confers phosphorylation-dependent intracellular trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35042–35048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bardai FH, D’Mello SR. Selective toxicity by hdac3 in neurons: Regulation by akt and gsk3beta. J Neurosci. 31:1746–1751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5704-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitagawa K. Creb and camp response element-mediated gene expression in the ischemic brain. Febs J. 2007;274:3210–3217. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durukan A, Marinkovic I, Strbian D, Pitkonen M, Pedrono E, Soinne L, Abo-Ramadan U, Tatlisumak T. Post-ischemic blood-brain barrier leakage in rats: One-week follow-up by mri. Brain Res. 2009;1280:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaines P, Lamoureux J, Marisetty A, Chi J, Berliner N. A cascade of ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases regulates the differentiation and functional activation of murine neutrophils. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9451–9462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2674-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Leng Y, Tsai LK, Leeds P, Chuang DM. Valproic acid attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia: The roles of hdac and mmp-9 inhibition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:52–57. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.