Abstract

Objective:

To present 2 cases of entrapment of the saphenous nerve at the adductor canal affecting the infrapatellar branch, and to provide insight into the utilization of nerve tension testing for the diagnosis of nerve entrapments in a clinical setting.

Rationale:

Saphenous nerve entrapments are a very rare condition within today’s body of literature, and the diagnosis remains controversial.

Clinical Features:

Two cases of chronic knee pain that were unresponsive to previous treatment. The patients were diagnosed with an entrapment of the saphenous nerve at the adductor canal affecting the infrapatellar branch using nerve tension techniques along with a full clinical examination.

Intervention and Outcome:

Manual therapy and rehabilitation programs were initiated including soft tissue therapy, nerve gliding techniques and gait retraining which resulted in 90% improvement in one case and complete resolution of symptoms in the second.

Conclusion:

Nerve tension testing may prove to be an aid in the diagnosis of saphenous nerve entrapments within a clinical setting in order to decrease time to diagnosis and proper treatment.

Keywords: nerve, saphenous, entrapment, adductor canal

Abstract

Objectif :

présenter 2 cas de compression du nerf saphène interne au niveau du canal adducteur affectant la branche sous-rotulienne, et donner un aperçu de l’utilisation des tests de tension nerveuse pour le diagnostic des compressions nerveuses dans un cadre clinique.

Justification :

les compressions du nerf saphène interne sont une affection très rare dans les documents scientifiques actuels, et le diagnostic reste controversé.

Caractéristiques cliniques :

deux cas de douleur chronique au genou qui ne répondaient pas au traitement précédent. Le diagnostic des patients souffrant d’une compression du nerf saphène interne au niveau du canal adducteur affectant la branche sousrotulienne a été réalisé grâce à des techniques de tension nerveuse et un examen clinique complet.

Intervention et résultat :

des programmes de thérapie manuelle et de réadaptation ont été lancés, y compris le traitement des tissus mous, les techniques de glissement nerveux et la rééducation de la démarche, qui se sont traduits par une amélioration de 90 % dans un cas et la disparition complète des symptômes dans le second.

Conclusion :

les tests de tension nerveuse peuvent s’avérer être une aide au diagnostic des compressions du nerf saphène dans un milieu clinique permettant de réduire le temps de diagnostic et de traitement.

Keywords: nerf, saphène, compression, canal adducteur

Introduction

Saphenous nerve entrapment affecting the infrapatellar branch can be a difficult diagnosis to make due to the intimate relationship of the nerve to many other pain generating structures in the knee. Saphenous nerve entrapment has been reported within the literature to be associated with or mimic a number of conditions including lumbar radiculopathy,1,2 patellofemoral disorders,2 suprapatellar plica,2 tear of medial meniscus,3 tibial stress fracture,4 pes anserine tendonopathy or bursitis,1,4 osteochondritis dissecans,2 nonspecific synovitis2 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,5–8

It has been reported that less than 1% of adults presenting with lower extremity pain suffer from saphenous neuropathy,9,10 however injury to the saphenous nerve is associated with a number of surgical interventions commonly utilized in today’s medical community. Depending on the technique utilized, the incidence of sensory disturbances in patients who undergo arthroscopic surgery has been reported as 0.06% – 77%.11–16 With regards to meniscal repairs specifically it has been reported that saphenous nerve injury occurs in 1–20% of patients.3,17 Those undergoing ACL repairs are at risk of damage to the saphenous nerve at a rate of 30% – 59% depending on the technique utilized.16,18–24 In patients undergoing treatment for varicose veins, it has been reported that damage to the saphenous nerve occurs in 0.5–5% of those undergoing endovenous laser ablation25 and in up to 58% of those undergoing stripping of the great saphenous vein.26 While cases of saphenous neuropathy following trauma do exist in the literature they are extremely rare despite the nerve’s superficial location in the body and vulnerability during sport.10,27 A potential reason for this may lie in the diagnosis of this condition.

The diagnosis of saphenous nerve entrapment is a difficult one to make and is met with controversy within the literature. Nerve conduction studies as well as diagnostic corticosteroid or anesthetic injections have been discussed in the literature as means to diagnose this pathology, however authors argue on the merits of either intervention for the diagnosis.28–32 Furthermore, there is currently no literature available on the reliability or accuracy of these tests in the case of a saphenous nerve entrapment. The use of MRI and diagnostic ultrasound have also been discussed in the literature.10 All of these diagnostic tests pose financial and time limitations in the clinical setting, particularly for the manual practitioner. The purpose of the current paper is to present 2 cases of saphenous nerve entrapment at the adductor canal and to highlight a nerve tension technique to aid in the clinical diagnosis of this condition.

Case 1 Presentation

A 29 year old recreational female baseball player and runner presented with right sided knee pain that had been increasing for 1 year in duration. The pain initially presented 15 years prior following a direct blow to the anteromedial patella from a line drive in a game of baseball. Radiographs were taken at this time and no fracture was reported. The initial pain from the trauma subsided, however a constant throbbing sensation was felt throughout the right leg. Physical therapy was performed over a 4 year period including ultrasound, interferential current, taping techniques and rehabilitative exercises which had no effect on the pain.

The pain was described as fullness in the knee with associated dull aching throughout the right leg and occasional stabbing sensations felt at the inferomedial aspect of the right knee. Aggravating factors included prolonged standing, running, climbing or descending stairs. Pain during running would increase at the 4 minute mark and last for 24 hours. The pain was relieved by ice applied over the painful areas. The patient was a recreational runner, averaging between 10–15 kilometers per week, as well as participating in weight lifting and yoga. Within the past year a diagnosis of fat pad irritation of the right knee had been made and there was treatment for 7 months using Graston and muscle release techniques to the retinaculum of the knee, and affected soft tissue structures surrounding the joint. This had no effect on the patient’s symptoms.

On June 21st, 2011 the patient’s numerical pain rating scale was 10/10 immediately at the onset of running and her Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) was 71/80.33

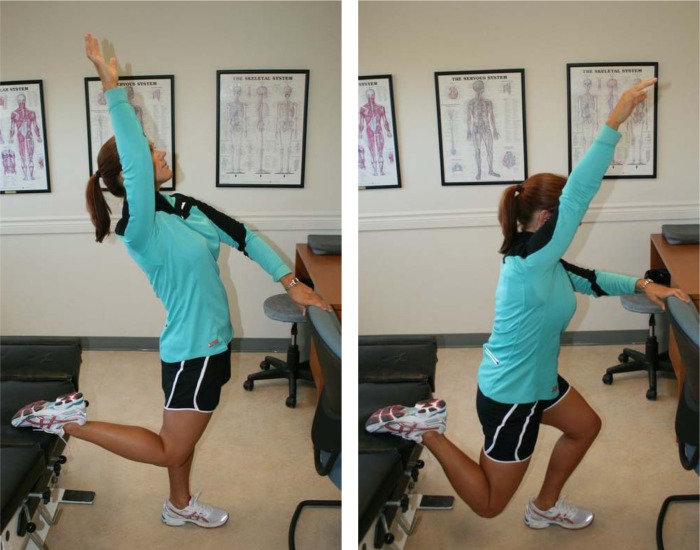

Physical examination revealed full and pain free range of motion in the right knee, hip and ankle. Palpation revealed pain and tenderness along the inferior pole of the patella, superomedial retinaculum of the patella, vastus medialis, adductor canal, sartorius and psoas muscles on the right. Ligament and meniscal testing of the knee was negative. The chief complaint was recreated when palpation of the medial thigh at the adductor canal was performed. The saphenous nerve was tensioned by placing the leg in hip extension and abduction with full knee flexion (Figure 1). In this position, palpation of the adductor canal as well as the femoral triangle was increasingly painful and recreated the patient’s chief complaint. During running gait analysis it was noted that the patient crossed midline resulting in an ‘egg beater’ gait pattern. The patient was diagnosed with saphenous nerve entrapment at the adductor canal affecting the infrapatellar branch.

Figure 1.

Position of neural tension for the saphenous nerve. Patient is placed in a side lying position with the hip extended and abducted and the knee flexed. In the present image the adductor canal is being palpated simultaneously in an attempt to recreat the patients chief complaint.

The patient was treated 2 times per week for 8 weeks using vibration therapy for the saphenous nerve, muscle release therapy to hypertonic musculature surrounding the saphenous nerve and nerve flossing (Figure 2 A&B). The patient was also advised to run on a marked track to help avoid crossing midline during running, as well as to avoid aggravating positions and activities.

Figure 2.

A & B Starting and finishing position for saphenous nerve gliding technique. Patient begins the motion in relative hip extension, abduction and slight knee flexion and progresses to increasing amounts of knee flexion while decreasing the amount of relative hip extension in an effort to maintain a constant amount of neural tension while gliding the nerve along its anatomical path.

At the end of the treatment plan the patient subjectively reported a 90% recovery to date and was able to run 50 minutes without pain and experienced no pain after running. On September 13th, 2011 numerical pain rating scale was 5/10 at 30 minutes of running and on December 10th, 2011 her score was 5/10 when running past 50 minutes duration. LEFS scores were 70/80 on September 13th, and 69/80 on December 10th.

Case 2 Presentation

A 55 year old recreational runner and triathlete presented with a complaint of chronic right medial knee pain. The pain began after the patient was climbing down from a shelf at work and felt a pull in the knee as she put her foot down onto the ground. She did not report any pops or snaps, swelling or any radiation or paresthesia into the leg, foot, hip or low back. The pain had quickly subsided however she went for a jog shortly after the initial pain for a distance of 4.5 km and felt pain return. The pain in the knee went away following the run. The patient had a previous history of similar knee pain due to her training regimen that included running, biking and swimming. She had previously been diagnosed with pes anserine bursitis secondary to lower kinetic chain dysfunction and had responded well to treatment including extremity manipulation, soft tissue therapy of the lower limb bilaterally and rehabilitation including stretches to the affected tissues.

Physical examination revealed point tenderness at the pes anserine insertion, tenderness of the muscle bellies and tendons of the gracilis, sartorius, and semitendinosus. A further assessment of her kinetic chain showed muscle tenderness in the psoas, gluteus medius and minimus, and at the border of her hamstring and adductor musculature. Joint restriction of her right ankle mortise and subtalar joints was also noticed. These findings were all consistent with her previous presentations and she was subsequently diagnosed with right pes anserine bursitis secondary to lower kinetic chain dysfunction.

The patient was treated 4 times over the course of 5 months and would report improvement following therapy but the pain would resume fairly soon after (sometimes within 2 hours of treatment). Her lack of progress was felt to be due to her continued training and her lack of consistent treatment. After 5 months of similar pain, the patient was increasingly frustrated with the lack of results and her inability to train at her expected level. A re-evaluation of her condition included a check of her femoral and saphenous nerves which were painful on palpation along their path including the medial border of the tibia, pes anserine insertion, the medial joint line at the sartorius and gracilis (just adjacent to the adductor hiatus), the adductor canal, femoral triangle and lateral border of psoas. The saphenous nerve was then placed in a position of tension (Figure 1) and palpation of the previously tender spots was increasingly painful. While in the position of tension, palpation of the adductor canal and medial joint line recreated the pain of chief complaint at the pes anserine insertion. The patient’s diagnosis was revised to peripheral entrapment of the saphenous nerve at the adductor canal.

The patient’s treatment plan was revised to include acupuncture of the right leg, myofascial release of the saphenous and femoral nerves, vibration therapy as needed and nerve flossing of the femoral and saphenous nerves (Figure 2 A&B). She felt a major improvement after the first visit and was treated twice more over a 2 week period. A follow up two months after the third visit revealed a complete resolution of the knee pain after the last visit. She reported being pain free for the two months even with training that included running, biking and swimming.

Discussion

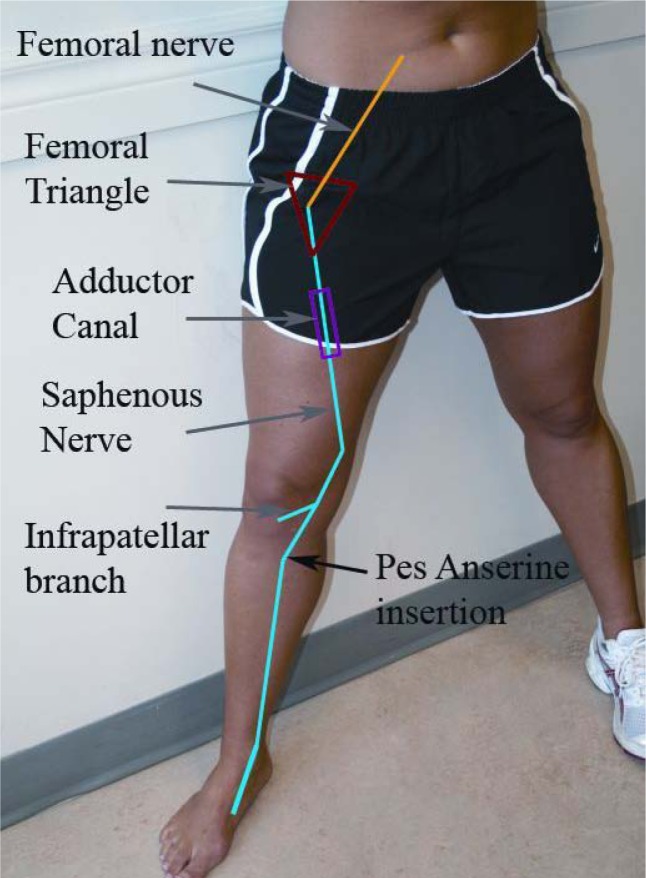

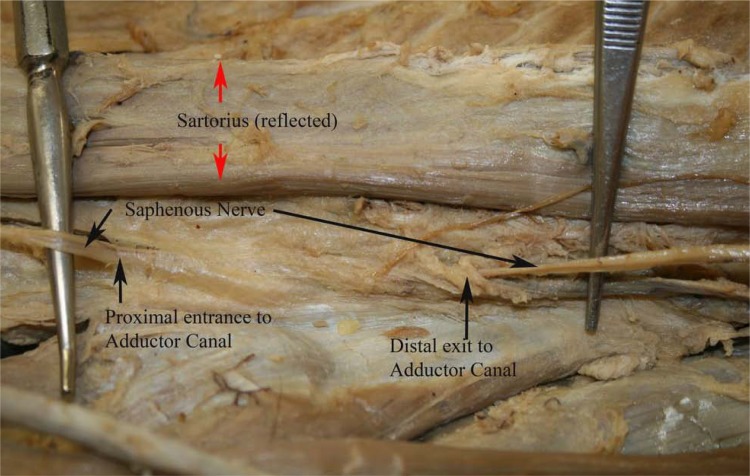

The saphenous nerve is a purely sensory nerve, and is the longest terminal branch of the posterior division of the femoral nerve, arising from the L3 and L4 nerve roots.10,34 From its origin below the level of the inguinal ligament, it travels within the thigh anteriorly with the femoral artery, until it becomes more superficial where it runs with the saphenous vein (Figure 3).34,35 During its entire course in the thigh, the saphenous nerve runs deep to the sartorious muscle.34–36 Within the proximal third of the thigh, the nerve enters the subsartorial, adductor or Hunter’s canal, which is formed by a fibrous band spanning between the vastus medialis and the adductor magnus and adductor hiatus (Figure 4).10,34,37 Here the saphenous nerve joins with the saphenous branch of the descending genicular artery and both structures pierce the roof of the subsartorial canal just proximal to the adductor hiatus.10,34,35,37 It is at this point as well as within the adductor canal where the saphenous nerve is most susceptible to entrapment.

Figure 3.

Anatomical course of the saphenous nerve

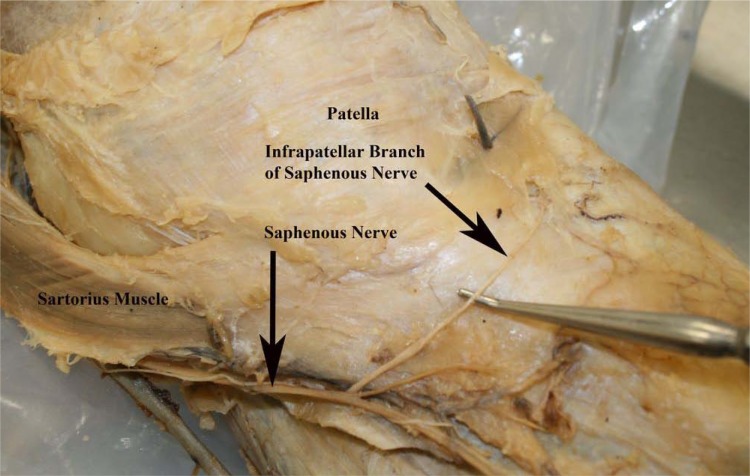

Figure 4.

Saphenous nerve entering and exiting the adductor canal deep to the reflected sartorius muscle.

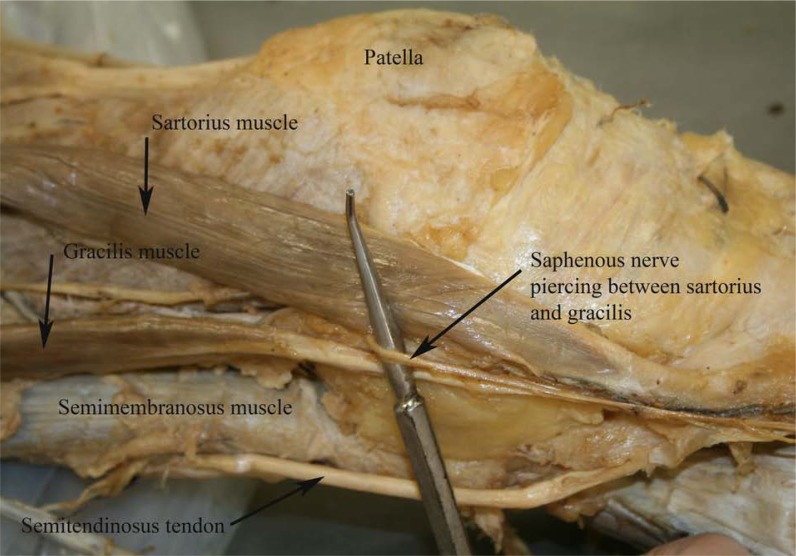

In addition to the saphenous nerve, contents of the subsartorial canal include the femoral vessels, the nerve to the vastus medialis, and other motor branches.37 After exiting the subsartorial canal, the saphenous nerve branches into its two terminal branches, the infrapatellar branch, which innervates the infrapatellar fat pad as well as the rest of the anteromedial knee, and the descending branch which provides the distal sensory innervation to the skin and fascia on the anteromedial aspect of the leg and foot to the first metatarsal (Figure 5), as well as articular branches to the knee and ankle.10,34–36

Figure 5.

Sensory distribution of the saphenous nerve

The descending branch pierces the sartorius muscle or the superficial fascia between the gracilis and sartorious muscles to enter the subcutaneous tissue and travel distally in the leg.10 The infrapatellar branch has also been described as piercing through the sartorious muscle to reach the subcutaneous layer.38 At the level of the knee, the infrapatellar branch is susceptible to entrapment between the prominent edge of the medial femoral condyle and the tendon of the sartorious muscle (Figure 6).10,39 The infrapatellar branch commonly presents with two terminal branches, superior and inferior, which have been identified as having two possibly variations in their orientation about the knee.10,12,28,39 In the first variation the infrapatellar branch traverses across the proximal tibia medial to the patellar tendon, while in the second variation, the nerve passes laterally across the joint line and does not pass over the proximal tibia (Figure 7).12

Figure 6.

Saphenous nerve after it has exited the adductor canal passing between the sartorius and gracilis muscles at the level of the knee

Figure 7.

Saphenous nerve distal to the level of the knee giving rise to the infrapatellar branch and continuing into the distal leg

A clinical examination of a patient with suspected saphenous nerve entrapment should include thorough history and physical examinations. On historical examination patients will typically present with complaint of medial knee and or leg pain,9,29–32,40 pain with kneeling,11,41 and there may be an associated trauma to the saphenous nerve via blunt trauma or previous surgical procedures.10,32,41 The distribution of pain in saphenous nerve entrapment patients has been reported as at the knee (90%), thigh (7%) and calf (3%),35 and it may also be present at night.32 Physical examination may elicit hypoesthesia or dysesthesia in the absence of any motor weakness and a positive Tinel’s test at the site of injury.10 Patients may also present with pain on gait30,32,40,41 and resisted adduction or flexion at the hip,10,32,40 as well as pain on palpation at the adductor canal or the medial femoral condyle where the saphenous nerve pierces or wraps around the sartorius muscle.35 Pain may also be elicited with prone hip extension (reversed Lasegue’s sign) due to an increase in neural tension along the saphenous nerve.10 Nerve tension testing is a technique utilized in aiding a number of diagnoses including cervical and lumbar radiculopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome and a number of peripheral nerve entrapments. By placing a patient with suspected saphenous nerve entrapment into a position of hip extension and abduction with full knee flexion (Figure 3), the clinician may be able to create further tension along the nerve in an attempt to recreate symptoms and assist clinicians with making a difficult clinical diagnosis. Our patients presented with knee pain which was reproduced in a position of neural tension for the saphenous nerve and increased in intensity upon palpation at the adductor canal and femoral triangle.

Once a clinical diagnosis of saphenous nerve entrapment has been made, further diagnostic testing such as nerve conduction studies, diagnostic injections or advanced imaging may be warranted. In the presented cases, this diagnosis was not confirmed using nerve conduction testing, diagnostic injections or imaging. In a paper by Pendergrass et al., they report that despite having nerve conduction studies, MRI and ultrasound imaging in a case involving trauma to the adductor canal, the diagnosis of saphenous nerve entrapment was only considered after a thorough follow up clinical examination.10 While nerve blocks are being performed as part of the diagnostic criterion for a number of case series in the literature,1,29,30,35 this may not always be practical in a clinical setting, particularly when a trial of conservative treatment is going to be employed.

Treatments cited within the literature for saphenous nerve entrapments typically include corticosteroid injection and surgical debridement of any fibrous tissue surrounding the nerve.9,10 To date there are no cases reported in the literature on manual therapy for the treatment of this condition. There is however a body of literature reporting on manual therapy for the treatment of a number of peripheral nerve entrapments including cubital tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, superficial fibular nerve entrapment and femoral nerve entrapment.42–48 Within this literature, techniques utilized to treat the entrapment include nerve gliding, joint manipulation, soft tissue techniques, taping techniques and rehabilitative exercises to address joint dyskinesis.42–46,48–50 In 2008, Coppieters et al. showed that an increase in nerve excursion of up to 30% can be seen in nerve gliding techniques versus nerve tensioning techniques, and showed up to 12.6mm of excursion of the median nerve using gliding techniques.50 This data provides insight into the utilization of nerve gliding, vibration and manual therapy techniques for saphenous nerve entrapments. Caution should be utilized what selecting conservative treatment techniques for nerve entrapments as the literature available on these techniques is largely comprised of case reports and clinical commentary which limit our understanding of the impact a given treatment may truly have and what role natural history plays in a patient’s recovery.

Due to the rarity of saphenous nerve entrapments, little is known on the prognosis or natural history for these patients. Difficulty in diagnosing this pathology warrants further research into its diagnosis, natural history and prognosis in a primary care setting. Diagnostic difficulties may be lessened through the systematic usage of nerve course palpation, nerve tensioning and palpation during neural tensioning, with the intent to recreate the patients chief complaint. The utilization of these techniques may provide a key clinical tool for clinicians to utilize in the early detection and treatment of saphenous nerve entrapments and should be explored in future research.

Conclusions

Saphenous nerve entrapments are a very rare condition within today’s body of literature. Difficulty in diagnosing this pathology may provide insight as to why there is such a limited body of evidence. Currently the main treatment options include surgical debridement and corticosteroid injections, however there is a body of evidence supporting the use of many manual therapy techniques for the treatment of various nerve entrapments throughout the body. Further insight into the utilization of palpation and nerve tension testing for the diagnosis of saphenous nerve entrapment in a clinical setting may pave the road for further insight into this rarely reported condition.

References

- 1.Ahadi T, Raissi GR, Togha M, Nejati P. Saphenous neuropathy in a patient with low back pain. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2010;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1749-7221-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saal JA, Dillingham MF, Gamburd RS, Fanton GS. The pseudoradicular syndrome. Lower extremity peripheral nerve entrapment masquerading as lumbar radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;13(8):926–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espejo-Baena A, Golano P, Meschian S, Garcia-Herrera JM, Serrano Jimenez JM. Complications in medial meniscus suture: a cadaveric study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(6):811–816. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peck E, Finnoff JT, Smith J. Neuropathies in runners. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(3):437–457. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poehling GG, Pollock FE, Jr, Koman LA. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the knee after sensory nerve injury. Arthroscopy. 1988;4(1):31–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(88)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan SS. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the knee. Treatment using continuous epidural anesthesia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(7):1110–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz MM, Hungerford DS. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy affecting the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(5):797–803. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B5.3680346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finsterbush A, Frankl U, Mann G, Lowe J. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the patellofemoral joint. Orthop Rev. 1991;20(10):877–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumenthaler M, Schlaick H. Peripheral Nerve Lesions, Diagnosis and Therapy. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pendergrass TL, Moore JH. Saphenous neuropathy following medial knee trauma. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(6):328–334. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueroa D, Calvo R, Vaisman A, Campero M, Moraga C. Injury to the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve in ACL reconstruction with the hamstrings technique: clinical and electrophysiological study. Knee. 2008;15(5):360–363. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mochida H, Kikuchi S. Injury to infrapatellar branch of saphenous nerve in arthroscopic knee surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(320):88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papastergiou SG, Voulgaropoulos H, Mikalef P, Ziogas E, Pappis G, Giannakopoulos I. Injuries to the infrapatellar branch(es) of the saphenous nerve in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with four-strand hamstring tendon autograft: vertical versus horizontal incision for harvest. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):789–793. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman OH, Fox JM, Snyder SJ, Del PW, Friedman MJ, Ferkel RD, et al. Arthroscopy--”no-problem surgery”. An analysis of complications in two thousand six hundred and forty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(2):256–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Small NC. Complications in arthroscopic surgery performed by experienced arthroscopists. Arthroscopy. 1988;4(3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(88)80030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portland GH, Martin D, Keene G, Menz T. Injury to the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of horizontal versus vertical harvest site incisions. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(3):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plasschaert F, Vandekerckhove B, Verdonk R. A known technique for meniscal repair in common practice. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(8):863–868. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kartus J, Movin T, Karlsson J. Donor-site morbidity and anterior knee problems after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autografts. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(9):971–980. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.28979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertram C, Porsch M, Hackenbroch MH, Terhaag D. Saphenous neuralgia after arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with a semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):763–766. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.4820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter LY, Louis DS, Ricciardi JR, O’Connor GA. The saphenous nerve: its course and importance in medial arthrotomy. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(4):227–230. doi: 10.1177/036354657900700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kartus J, Lindahl S, Stener S, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patellar tendon after harvesting its central third: a comparison between traditional and subcutaneous harvesting techniques. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(6):587–593. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.015058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kartus J, Magnusson L, Stener S, Brandsson S, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J. Complications following arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A 2-5-year follow-up of 604 patients with special emphasis on anterior knee pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7(1):2–8. doi: 10.1007/s001670050112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda A, Shino K, Horibe S, Nakata K, Buccafusca G. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with multistranded autogenous semitendinosus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(4):504–509. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sgaglione NA, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL, Gold DA, Panariello RA. Primary repair with semitendinosus tendon augmentation of acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(1):64–73. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veverkova L, Jedlicka V, Vlcek P, Kalac J. The anatomical relationship between the saphenous nerve and the great saphenous vein. Phlebology. 2011;26(3):114–118. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2010.010011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramasastry SS, Dick GO, Futrell JW. Anatomy of the saphenous nerve: relevance to saphenous vein stripping. Am Surg. 1987;53(5):274–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon GC. Traumatic prepatellar neuralgia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1952;34-B(1):41–44. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.34B1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.House JH, Ahmed K. Entrapment neuropathy of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve. Am J Sports Med. 1977;5(5):217–224. doi: 10.1177/036354657700500509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopell HP, Thompson WA. Knee pain due to saphenousnerve entrapment. N Engl J Med. 1960;263:351–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196008182630707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mozes M, Ouaknine G, Nathan H. Saphenous nerve entrapment simulating vascular disorder. Surgery. 1975;77(2):299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tranier S, Durey A, Chevallier B, Liot F. Value of somatosensory evoked potentials in saphenous entrapment neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(6):461–465. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.6.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worth RM, Kettelkamp DB, Defalque RJ, Duane KU. Saphenous nerve entrapment. A cause of medial knee pain. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12(1):80–81. doi: 10.1177/036354658401200114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther. 1999;79(4):371–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luerssen TG, Campbell RL, Defalque RJ, Worth RM. Spontaneous saphenous neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1983;13(3):238–241. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romanoff ME, Cory PC, Jr, Kalenak A, Keyser GC, Marshall WK. Saphenous nerve entrapment at the adductor canal. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(4):478–481. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore KL, Dalley AF. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horn JL, Pitsch T, Salinas F, Benninger B. Anatomic basis to the ultrasound-guided approach for saphenous nerve blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(5):486–489. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181ae11af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le CT, Lagier A, Pirro N, Champsaur P. Anatomical study of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve using ultrasonography. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(1):50–54. doi: 10.1002/mus.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tifford CD, Spero L, Luke T, Plancher KD. The relationship of the infrapatellar branches of the saphenous nerve to arthroscopy portals and incisions for anterior cruciate ligament surgery. An anatomic study. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):562–567. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280042001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartzman RJ, Maleki J. Postinjury neuropathic pain syndromes. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83(3):597–626. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon GC. Traumatic prepatellar neuralgia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1952;34-B(1):41–44. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.34B1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anandkumar S. Physical therapy management of entrapment of the superficial peroneal nerve in the lower leg: A case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3109/09593985.2011.653709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russell BS. A suspected case of ulnar tunnel syndrome relieved by chiropractic extremity adjustment methods. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26(9):602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Medina McKeon JM, Yancosek KE. Neural gliding techniques for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review. J Sport Rehabil. 2008;17(3):324–341. doi: 10.1123/jsr.17.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson LA, Pizzari T, Balster S. Thoracic outlet syndrome part 2: conservative management of thoracic outlet. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sucher BM. Ultrasonography-guided osteopathic manipulative treatment for a patient with thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111(9):543–547. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2011.111.9.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Robinson ME, Price DD, George SZ. Heightened pain sensitivity in individuals with signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome and the relationship to clinical outcomes following a manual therapy intervention. Man Ther. 2011;16(6):602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coppieters MW, Bartholomeeusen KE, Stappaerts KH. Incorporating nerve-gliding techniques in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(9):560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diers DJ. Medial calcaneal nerve entrapment as a cause for chronic heel pain. Physiother Theory Pract. 2008;24(4):291–298. doi: 10.1080/09593980701738392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coppieters MW, Butler DS. Do ‘sliders’ slide and ‘tensioners’ tension? An analysis of neurodynamic techniques and considerations regarding their application. Man Ther. 2008;13(3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]