Background

One important reason patients consult primary care professionals, including general practitioners and chiropractors, is for musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions.1 Musculoskeletal conditions (spinal pain, consequences of injuries, osteoporosis, and arthritis) result in an enormous social, psychological, and economic burden to society1–8, and are the leading cause of physical disability.9 Chiropractic is a regulated health profession (serving approximately 10% of the population)10 that has contributed to the health and well-being of North Americans for over a century.

Despite available evidence for optimal management of back and neck pain11–13, poor adherence to clinical practice guidelines and wide variations in services have been noted.12,14,15 Utilization of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) is an important way to help implement research findings into clinical practice. Guidelines aim to describe appropriate care based on the best available scientific evidence and broad consensus while promoting efficient use of resources.16,17 These tools have the potential to improve the quality and safety of healthcare.18,19

Over a decade ago, the Canadian Chiropractic Association (CCA) and the Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory and Education Accrediting Boards (CFCREAB or Federation) launched the CPG project to develop clinical practice guidelines in order to improve chiropractic care delivery in Canada. Guidelines developed by the CPG project include the management of neck pain due to whiplash injuries20, headaches21, and neck pain not due to whiplash22,23 (an update of which is expected by the end of 2013).

Recent advances in methods to conduct knowledge synthesis24, derive evidence-based recommendations25, adapt high quality guidelines26, and increase the uptake of Clinical Practice Guidelines27,28 have prompted an update of the DIER (development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision) Plan published in the JCCA (Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association) in 2004.29 The 140 page report was submitted to the stakeholders of the Guideline Initiative for consideration. The report updates the structure, methods and procedures for the development, dissemination and implementation of clinical practice guidelines in chiropractic. It is anticipated that new updates will be necessary as the art and science of guideline development, dissemination and implementation continue to evolve and new standards are established. The Full Report will be available on the new Guideline Initiative website, expected to be up and running in the first quarter of 2014.

This is the first paper of a two part presentation of the Guideline Initiative and its expected deliverables. The second paper will present the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation framework which will be the foundation of the Initiative. We intend to engage clinicians, leaders and decision makers in the profession right from the beginning as integral participants of the overall strategy to enhance patient care.

Overall purpose of the Guideline Initiative:

The overall purpose is to develop evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines and to facilitate the utilization of these and existing guidelines among chiropractors. Further, it aims to enhance academic, clinical and research partnerships to help close the gap between research knowledge and its implementation in clinical practice in order to improve health outcomes.

Scope:

The scope of the Guideline Initiative is limited to non-specific MSK conditions commonly seen by chiropractors including adult spinal and extremity disorders, headaches, pediatric conditions (scoliosis), and pre-specified objectives (e.g., assessment and/or treatment of low back pain). Studies on musculoskeletal disorders resulting from destructive and progressive pathologies affecting the spine will be excluded. However, diagnostic and assessment studies related to ruling out fractures, dislocations and other pathologies will be included in the scope of the Guideline Initiative.

Fundamental principles and values:

Principles and values behind the process are as follows:

Guidelines produced by the Guideline Initiative will be developed using the best available evidence and involving stakeholders in a transparent and collaborative manner. Stakeholders include professional organizations, health care professionals, consumers, and organizations that fund or carry out research. CPGs should address multiple dimensions of decision making. Providing open access to products developed by the Guideline Initiative (e.g., technical reports, guidelines, practitioner guides, and tools to facilitate dissemination and implementation) is one of the primary principles.

Despite significant challenges related to the management of chronic MSK conditions and associated comorbidities, a large proportion of chiropractors are solo practitioners. Management of these complex conditions requires inter-professional collaborations to improve the probability of favorable patient outcomes. Work undertaken by the Initiative will reflect the fact that an increasing number of chiropractors practice in multidisciplinary environments in the private sector, and more recently in the public setting as well.

The Institute of Medicine (2011) recently revised the definition of Clinical practice guidelines as: ‘Statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harm of alternative care options’.30

Primary objectives of the Guideline Initiative:

-

To identify existing best practices for the management of patients with MSK conditions in the area of primary care AND to identify clinical areas where there is a need to develop best practice guidelines.

Sub-objectives

To complete systematic searches and critical reviews of the scientific literature on MSK conditions, including the epidemiology, assessment/diagnosis, prognosis, economic costs when possible, and treatment of MSK disorders;

To identify and compare the relative risks of treatments (harm) of MSK conditions;

To develop guideline recommendations using a process that is scientifically sound and takes into account the views of end users (clinicians and patients), leaders/decision makers, and third party payers.

To integrate the evidence on harm/benefit trade-off with patient preferences.

-

To promote the use of best available evidence and expert consensus to inform clinical decision making in order to improve the quality of care of patients with MSK conditions.

Sub-objectives

To develop knowledge translation strategies and to help disseminate and implement these to increase guideline utilization, thus improving patient care and health.

To complete original Knowledge Translation (KT) research to assess the level of uptake of CPG recommendations.

Target audience:

The primary audience for the use of the guidelines are chiropractors (and their patients). The Guideline Initiative acknowledges that a secondary audience may take considerable interest in the recommendations, including other health disciplines, third party payers, attorneys and expert witnesses.

Structure of the Guideline Initiative:

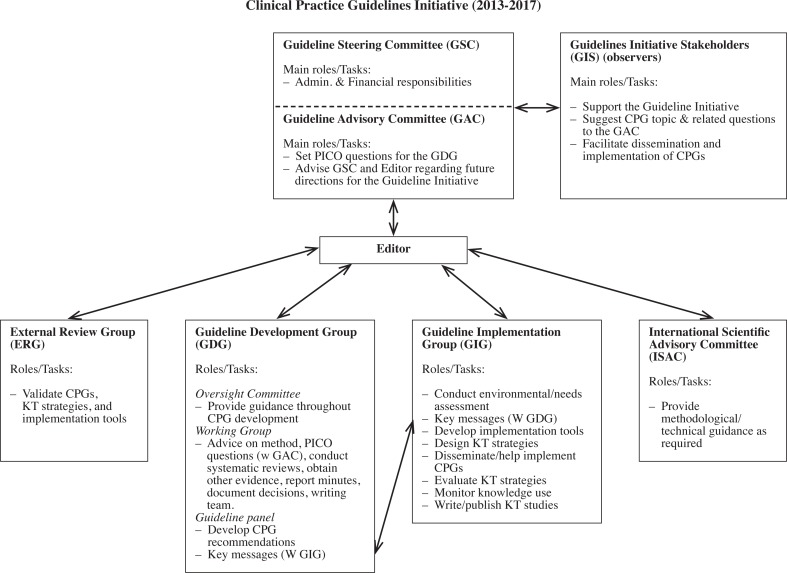

Diagram 1 illustrates the structure of the Initiative.

Diagram 1.

Structure of the Guideline Initiative

Composition of the Guideline Initiative working groups:

There is consistent empirical evidence that the composition of guideline development groups influence the resulting recommendations. Further, the Institute of Medicine recommends developing patient-centered guidelines using multidisciplinary and international collaborations (IOM, 2011). The Guideline Initiative includes individuals from all relevant professional groups, and has established a partnership, the North-Atlantic Research Consortium (NARC), uniting researchers from four other countries (Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, UK) to help develop, disseminate and implement CPGs among chiropractors.

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs):

Since the first LBP guideline was released in 1987 by the Quebec Task Force, there has been a steady worldwide interest, resulting in the publication of numerous CPGs in several countries over the past decades. More recent published CPGs are of better quality, although there remain areas of discrepancy between available guidelines that need to be resolved. Few guidelines created for chiropractors currently exist, and some of these are now outdated. Topics covered include: Neck pain with and without whiplash, Headaches, Diagnostic imaging, and Low back pain. CPGs should address multiple dimensions of decision making, including: effectiveness; harm; quality of life; health-service delivery issues (i.e., dissemination and implementation), provider and patient compliance, and resources, use and cost. Guidelines produced by the Guideline Development Group (GDG) will be developed using the best available evidence and involving stakeholders and health disciplines in a transparent and collaborative manner. Stakeholders include professional organizations, clinicians, consumers, and organizations that fund or carry out research.

Knowledge Translation: Despite available evidence for optimal management of MSK conditions, poor adherence to guidelines and wide variations in services have been noted across spine care providers.31, 32 Similar gaps (between what works and what is done in daily practice) have been observed for other conditions across the health care system in industrialized countries.33–35 Closing the research-practice gap involves modifying clinical practice, a complex and challenging endeavour of Knowledge Translation (KT). Putting knowledge into practice is a dynamic, iterative, and complex process. Success requires an integrated approach where all involved parties work together to select, tailor, and implement KT procedures.

Knowledge Translation Research:

KT research is the scientific study of the determinants, processes and outcomes of dissemination and implementation.36 The Guideline Dissemination/Implementation Group (GIG) will aim to regularly publish its work in peer reviewed journals.

Deliverables of the Guideline Initiative:

Deliverables of the Guideline Initiative during the next 4 years will include:

the dissemination and assisting with the implementation of the new Neck Pain Guideline,

the development of a clinical practice guideline on treatment-based classification systems for low back pain, and

updating an existing CCA-Federation CPG.

It is important to acknowledge that completion of projects undertaken by the Guideline Initiative is to a large extent contingent on both the work produced by a number of collaborators of the Guideline Initiative and ongoing funding from stakeholders.

Already, work is underway to ensure that these objectives are met. Progress made on projects undertaken by the Initiative will be regularly monitored. The Strategic work plan will be formally reviewed at the end of 2013 to identify areas of risk and modify the plan accordingly. The Strategic work plan will be assed annually thereafter.

It should be noted that both the Strategic Work Plan and the Full Report of the Guideline Initiative are living documents and continue to be updated regularly. A Gantt Project Management model will be used to help manage the various projects of the Initiative.

Questions regarding the Guideline Initiative, supporting documents and projects may be directed to Dr. André Bussières DC, PhD, FCCS(C), Editor-In–Chief of the Guideline Initiative at: andre.bussieres@mcgill.ca.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Francine Denis DC for reviewing this manuscript.

References

- 1.McBeth J, Jones K. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:403–425. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari R, Russell AS. Regional musculoskeletal conditions: neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(02)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, Côté P, Haldeman S, Ammendolia C, Carragee E, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S39–51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asche C, Kirkness C, McAdam-Marx C, Fritz J. The societal costs of low back pain: data published between 2001 and 2007. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J. 2008;8:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäkelä M, Heliövaara M, Sievers K, Knekt P, Maatela J, Aromaa A. Musculoskeletal disorders as determinants of disability in Finns aged 30 years or more. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:549–559. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90128-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Guzman J, Peloso P, Nordin M, Hurwitz E, van der Velde G, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S52–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643ece. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun S, Liu G, L H: Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29:79–86. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000105527.13866.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs J, Andersson G, Bell J, Weinstein S, Dormans J, Furman M, Lane N, Puzas J, St. Clair E, Yelin E. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. Prevalence, societal and economic costs. The Bone and Joint Decade. http://www.boneandjointburden.org/chapter_downloads/index.htm. 2008.

- 10.McManus E, Mior S. Impact of provincial subsidy changes on chiropractic utilization in Canada. Chiropr Educ. 2013;27:73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koes B, van Tulder M, Lin C-W, Macedo L, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. European Spine J. 2010;19:2075–2094. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, Caroll LJ, Nordin M, Guzman J, Peloso PM, Holm LW, Côté P, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Treatment of Neck Pain: Noninvasive Interventions Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S123–S152. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181644b1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordin M, Carragee EJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Weiner SS, Hurwitz EL, Peloso PM, Guzman J, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ, Holm LW, et al. Assessment of neck pain and its associated disorders: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S101–122. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181644ae8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haldeman S, Dagenais S. A supermarket approach to the evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2008;8:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurwitz E, Chiang L-M. A comparative analysis of chiropractic and general practitioner patients in North America: Findings from the joint Canada/United States survey of health, 2002-03. BMC Health Services Research. 2006;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field M, Lohr K. National Academy Press. 1990. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program; p. 38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ Clinical Research Ed. 1999;318:527–530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:385–392. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimshaw J, Russell I. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–1322. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw L, Descarreaux M, Bryans R, Duranleau M, Marcoux H, Potter B, Ruegg R, Watkin R, White E. A systematic review of chiropractic management of adults with Whiplash-Associated Disorders: recommendations for advancing evidence-based practice and research. Work. 2010;35:369–94. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryans R, Descarreaux M, Duranleau M, Marcoux H, Potter B, Ruegg R, Shaw L, Watkin R, White E. Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Chiropractic Treatment of Adults With Headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34:274–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CCA•CFCREAB-CPG GDC. Anderson-Peacock E, Blouin JS, Bryans R, Danis N, Furlan A, Marcoux H, Potter B, Ruegg R, Gross Stein J, White E. Chiropractic clinical practice guideline: evidence-based treatment of adult neck pain not due to whiplash. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005;49(3):158–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CCA•CFCREAB-CPG GDC. Anderson-Peacock E, Bryans R, Descarreaux M, Marcoux M, Potter B, Ruegg R, Shaw L, Watkin R, White E. A Clinical Practice Guideline Update from The CCA•CFCREAB-CPG. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2008;52(1):7–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Moher D. The art and science of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GRADE WG Grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations (GRADE) Available at: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/. Accessed Oct 20, 2013.

- 26.The ADAPTE Collaboration The ADAPTE Manual and Resource Toolkit. 2009. The ADAPTE Collaboration Version 2.0. ; Available from: http://www.gi-n.net/activities/adaptation/introduction-g-i-n-adaptation-wg. Accessed October 20 2013.

- 27.Collaboration D. Developing and Evaluating Communication Strategies to Support Informed Decisions and Practice Based on Evidence (DECIDE) Available at: http://www.decide-collaboration.eu/. Accessed Oct 20, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Lavis J, Hill S, Squires J. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implementation Sci. 2012;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CCA_CFCRB The Canadian Chiropractic Association and the Canadian Federation of Chiropractic RegulatoryBoards Clinical Practice Guidelines Development Initiative (The CCA/CFCRB-CPG) development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision (DevDIER) plan. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2004;48:56–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham G, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Institute of Medicine, Shaping the Future for Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, Caroll LJ, Nordin M, Guzman J, Peloso PM, Holm LW, Côté P, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Treatment of Neck Pain: Noninvasive Interventions Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33:S123–S152. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181644b1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haldeman S, Dagenais S. A supermarket approach to the evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2008;8:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care. 2001;39:1146–1154. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuster MA, Elizabeth A, McGlynn R, Brook H. How Good Is the Quality of Health Care in the United States? Milbank Q. 1998;76:517–563. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curran JA, Grimshaw JM, Hayden JA, Campbell B. Knowledge translation research: The science of moving research into policy and practice. J Continuing Edu Health Pro. 2011;31:174–180. doi: 10.1002/chp.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]