Abstract

Acculturative stress negatively impacts the physical and mental health of Latino immigrants. Little is known about the pre-immigration resources that may influence the acculturative stress of Latino immigrants. Religion plays a prominent role in Latino culture and may prove to be an influential resource during difficult life transitions, such as those experienced during the immigration process. The present study examines the association between religious coping resources prior to immigration and acculturative stress after immigration within a multiethnic sample of 527 adult Latinos who have lived in the United States for less than 1 year. Path analyses revealed that pre-immigration external religious coping was associated with high levels of post-immigration acculturative stress. Illegal immigrant status was associated with high levels of pre-immigration religious coping as well as post-immigration acculturative stress. These findings expand scientific understanding as to the function and effect of specific religious coping mechanisms among Latino immigrants. Furthermore, results underscore the need for future research, which could serve to inform culturally relevant prevention and treatment programs.

Keywords: acculturation, Latinos, immigrant, religious coping, religiosity

INTRODUCTION

The Latino population in the United States has experienced remarkably rapid growth over the past three decades. Statistics from the 2010 U.S. Census placed Latinos at approximately 50.5 million people, accounting for 16% of the total U.S. population. More than half of the growth in the total U.S. population between 2000 and 2010 was due to the increase in the Latino population. Specifically, within the past decade the number of Latinos in the United States grew by 43%, which was four times the growth in the total population (U.S. Census, 2011a). A distinctive characteristic of the Latino population in the United States is its large number of immigrants. Today, the majority of immigrants gaining entry into the United States are Latino (Caplan, 2007). It is anticipated that the population of the United States will rise to 438 million in 2050, from 296 million in 2005, and 82% of the increase will be due to immigrants arriving from 2005 to 2050. The Latino population, already the largest minority group, will triple in size and will account for most of the nation’s population growth from 2005 to 2050 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2009).

Although the visibility of Latino immigrant experiences appears to be growing in the social science literature, there is an apparent gap in knowledge concerning the pre-immigration experiences of Latino immigrants. The majority of the literature focuses on the immigrant experience within the United States. Yet, Latino immigrants bring with them a wide array of resources or capital (obtained through pre-immigration experiences) including values, assets, social connections, and coping styles. According to Nee and Alba (2004), pre-immigration experiences considerably influence immigrants’ adaptation patterns to the United States. The lack of information in the literature on pre-immigration experiences hinders our capacity to fully understand Latino immigrants’ acculturation experience in the United States. Thus, in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding on the scope of the immigrant experience, the social work field should begin to examine immigrants’ experiences within their country of origin. This knowledge may offer not only a richer contextual understanding of the lives of Latino immigrants, but can provide important background information that can be utilized in assessing social functioning and mental health. In this regard, an understanding of pre-immigration experiences can assist social workers in developing service delivery models that are more suitable in meeting the needs of Latino immigrants (Drachman & Paulino, 2004).

Based on Cabassa’s (2003) study on acculturation, the present study takes pre-immigration factors into consideration in order to explain the negative experiences related to the acculturation process, namely, acculturative stress. As noted by Cabassa (2003), an understanding of preimmigration context is essential when studying how individuals are learning to deal with a new cultural situation. By pre-immigration context, Cabassa refers to both society-of-origin factors (e.g., political, economic, and social environment) and individual-level factors (e.g., social support networks, reason for immigration, role in the immigration decision). Our study focuses on the individual-level pre-immigration factors, specifically religious coping resources, and their influence on the acculturative stress of recent Latino immigrants in the United States.

LITERATURE REVIEW

One of the most prominent factors attributed to declining physical and mental health patterns among Latino immigrants has been the acculturation process (Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Hayes Bautista, 2005). Acculturation has been defined as the manner by which immigrants’ attitudes and behaviors merge with those of the predominant cultural group as a result of exposure to the new culture (Berry, 1997). A common experience among recent immigrants is feelings of stress as a result of the acculturation process. This form of stress consists of psychological or social stressors encountered by an individual due to an incongruence of beliefs, values, and other cultural norms between their country of origin and their host country (Cabassa, 2003). Acculturative stress is usually brought about by factors such as legal status; language barriers; difficulties assimilating to beliefs, values, and norms of the dominant culture; perceived feelings of inferiority; and discrimination (Berry, 1997). Feelings of acculturative stress have been linked to greater incidences of anxiety, depression (Crockett et al., 2007; Mejia & McCarthy, 2010), post-traumatic stress disorder (Pole, Best, Metzler, & Marmar, 2005), as well as a variety of other conditions that lead to poor physical and mental health outcomes among Latinos (Finch & Vega, 2003; Vega & Amaro, 1994).

Extensive evidence suggests that religion comes to the forefront as a way to deal with stress for many individuals (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Chatters, 2000; Ellison & Levin, 1998; Pargament, 1997, 2002a,b). Religious coping can be defined as “the use of cognitive and behavioral techniques, in the face of stressful life events, that arise out of one’s religion or spirituality” (Tix & Frazier, 1998, p. 411). Pargament’s (1997) review of the psychology of religion revealed that religious coping styles are conceptually distinct from nonreligious coping styles and uniquely influence psychosocial health above and beyond the effects of nonreligious coping. Furthermore, religious coping styles have been found to be better predictors of mental health outcomes of stressful situations than measures of religiosity alone (e.g., frequency of church attendance, involvement in church-related activities, frequency of prayer).

These coping styles may be particularly applicable for many in the Latino culture, where religiosity is considered to be a central value (Magaña & Clark, 1995; Mausbach, Coon, Cardenas, & Thompson, 2003; Menjivar, 2003; Plante, Manuel, Menendez, & Marcotte, 1995; Steffen & Merrill, 2011). Not only is religion an important aspect of Latino culture, but Latinos have been found to use religious coping mechanisms more frequently than their non-Latino white counterparts (Valle, 1994) to deal with stressful conditions (Coon et al., 2004) and illness such as arthritis (Abraido-Lanza, Vasquez, & Echeverria, 2004).

Given previous findings it stands to reason that the frequent use of religious coping by Latinos may serve as a protective factor against acculturative stress. Less acculturated Latinos use religious coping more often than their more acculturated counterparts (Mausbach et al., 2003). Yet little is known about the extent to which religious coping styles Latino immigrants bring with them from their home countries influence the acculturative stress experienced after arrival to the United States. Because religious coping styles have been found to remain relatively constant through time (Pargament, 1997), it is anticipated that the religious coping resources used prior to immigration will have a distinct impact on the acculturative stress experienced by recent Latino immigrants post-immigration.

Historically, studies examining the effects of religious resources on the stress and health outcomes of minorities have focused on African-Americans (Szymanski & Obiri, 2011; Molock, Purl, Matlin, & Barksdale, 2006; Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004). Previous research suggests that religious resources such as prayer and religious service attendance appear to temper the effects of discrimination, and other forms of psychological stress among African-Americans (Holt, Lewellyn, & Rathweg, 2005; Reid & Smalls, 2004; Wallace & Bergeman, 2002). The few studies that have explored these relationships among U.S. Latinos (Ellison, Finch, Ryan, & Salinas, 2009; Finch & Vega, 2003) report conflicting findings. Finch and Vega (2003) investigated Mexican-origin adults and found that participants who engaged in religious support-seeking behaviors experienced less acculturative stress, and were less likely to report being in poor health. In a more recent study using the same data set, Ellison and colleagues (2009) reported that religious involvement appeared to exacerbate the effects of acculturative stress on depressive symptoms of Mexican-origin adults.

As noted, previous research on the relationship between acculturative stress and religious resources has led to inconclusive findings. Therefore, the pathways by which religious coping affects acculturative stress still remain unclear. In past studies (Finch & Vega, 2003; Ellison et al., 2009), samples have consisted specifically of Latinos of Mexican or Puerto Rican descent and have included both U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinos. The ways in which religion functions in the coping process among other Latino subgroups, and specifically in recent Latino immigrants, is virtually unknown. The recency of immigration is of prominent concern when looking at levels of acculturative stress among Latinos, as the highest rates of acculturative stress are usually experienced within the first two years of immigration (Gil & Vega, 1996). Furthermore, an extensive review of literature revealed that no investigations have studied the effects that religious coping styles brought by Latinos from their country of origin have on the acculturative stress of recent Latino immigrants (Dunn & O’Brien, 2009).

The Present Study

The present study seeks to investigate the relationship between pre-immigration religious coping styles and postimmigration acculturative stress among recent Latino immigrants. The study focuses on internal and external religious coping mechanisms. Internal religious coping primarily involves cognitive/private coping strategies such as engaging in contemplative prayer or looking toward a higher power to facilitate cognitive restructuring of the meaning of a stressful event (Boudreaux, Catz, Ryan, Amaral-Melendez, & Brantley, 1995). Internal religious coping may encourage a reevaluation of the meaning of problematic conditions, reframing them as opportunities for spiritual growth or learning, and being part of a broader divine plan (Hill & Pargament, 2008). External religious coping involves social behavioral strategies such as seeking assistance from religious leaders or becoming involved with church activities. This style of coping facilitates an individual’s ability to tap into external religious resources such as pastoral counseling and church programs (Chatters, 2000; Hill & Pargament, 2008). External religious coping has been found to provide individuals with access to social support, social integration, instrumental aid (e.g., goods and services) (Chatters, 2000), and socio-emotional assistance (Ellison & Levin, 1998).

Given the inconclusive findings regarding the association between religious coping and acculturative stress among Latinos, the current study aims to contribute knowledge concerning the direction and magnitude of this relationship among recent immigrants. We acknowledge the importance of context in the immigration experience by statistically accounting for participant education, income, legal status (legal or illegal immigrant), and time in the United States when examining relations between pre-immigration religious coping styles and post-immigration acculturative stress.

METHODS

Procedures

Analyses for this cross-sectional study utilized baseline data from a longitudinal investigation of the influence of pre-immigration factors on health behavior trajectories of recent Latino immigrants in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Inclusion criteria for the parent study included 18- to 34-year-old Latinos who have recently (less than 1 year) immigrated to the United States from a Latin American country. For longitudinal retention purposes, participants were required to provide names and contact information for two people in the United States and one person in their country of origin that would know how to reach them if they moved.

Participants were recruited through announcements posted at several community-based agencies providing legal services to refugees, asylum seekers, and other documented and undocumented immigrants in Miami-Dade County. Information about the study was also disseminated at Latino community health fairs and neighborhood activity locales (e.g., domino parks in the Little Havana section of Miami). Announcements were also posted in Latino communities and on Web sites such as www.craigslist.org and an employment Web site that Latinos access to find work in Miami-Dade County (see De La Rosa, Babino, Rosario, Valiente, & Aijaz, 2012, for a comprehensive description of recruitment efforts).

Respondent-driven sampling was the primary recruitment strategy for this investigation. This technique is an effective strategy in recruiting participants from hidden or difficult-to-reach populations (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2003). For instance, undocumented Latino immigrants are often a hidden population due to the sensitivity of their legal status in the United States. Given that approximately 25% of the U.S. Latino population consists of undocumented immigrants (Passel & Cohn, 2008), and that 30% of the present sample were undocumented immigrants, respondent-driven sampling was considered to be the most feasible sampling approach. This technique involved asking each participant (the seed) to refer three other individuals in their social network who met the eligibility criteria for the study and consented to be interviewed. Those participants were then asked to refer three other individuals. The procedure was followed for seven legs for each initial participant (seed), at which point a new seed would begin, thus limiting the number of participants that were socially interconnected. This process was undertaken in an effort to avoid skewing the respondent sample (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2003).

Participants were given the option to have the interview administered in English or Spanish. All interviews were conducted in Spanish. Interviews were completed in a location agreed upon by both the interviewer and participant. Most interviews were administered either in a participant’s home (61%), or a restaurant/coffee shop (25%). The remaining interviews (14%) were completed at the participants’ work, school, or other public location. Interviews were audio-recorded and reviewed by research assistants for quality control purposes.

There were a total of eight interviewers: five females and three males. All interviewers were bilingual Latinos of South American or Caribbean ethnicities. Ages of interviewers ranged from 23 to 48 years of age (M = 33.38, SD = 7.23). All interviewers held college degrees (four undergraduate and four graduate degrees). Interviewers were fluent in both English and Spanish. They received four days of training covering general interviewing techniques and procedures, safety, cultural competence, and human subject issues, administration of the interview protocol, and practice of interview protocol, including role-playing. Each interviewer was then sent out to administer one interview and shadow another interview for quality control. These interviews were audio-recorded and reviewed by experienced research staff to ensure adequate quality.

Sample

The present study used a sample of 527 recent Latino immigrants (45.7% females and 54.3% males). The sample used for the present study is unique in various ways. The sample consists of a distinctive and understudied sample of newly arrived Latino immigrants. The recent immigration status of the sample is an important element of the research design as religious coping has been found to be used more readily among less acculturated Latinos than in acculturated Latinos (Mausbach et al., 2003). Finally, the diverse Latino ethnic makeup of the study population is characteristic of the South Florida population (United States Census, 2011b).

Participants’ average length of time in the United States ranged between 1 and 12 months (M = 6.74 months, SD = 3.11). The primary motive for immigration reported by participants was economic reasons (58.8%), followed by reuniting with family members (23%), political (8.1%), and other (10.3%). The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 34 years (M age = 26.88, SD = 4.99). The education levels were as follows: 19% college degrees, 34% some college, 29% high school or equivalent degree, and 18% less than high school. The sample consisted of relatively low-income participants. The average total household income in the past 3 months reported by participants was $5,265.11 (SD = $5,148.32)—approximately $21,000 annually.

In terms of ethnic classification, the most prominent ethnic group was Cubans at 42%, followed by Colombians (18%), Hondurans (13%), and Nicaraguans (9%). Guatemalans, Venezuelans, and Peruvians each comprised approximately 3% of the sample. Bolivians, Uruguayans, Argentines, Chileans, Costa Ricans, Dominicans, Ecuadorians, El Salvadorians, Mexicans, and Panamanians each represented 2% or less of the sample. Approximately 70% of participants were legal immigrants, while 30% were undocumented illegal immigrants.

Measures

Demographics

A demographics form assessed, in part, participant time in the United States, total household income during the three months after immigration, and level of education (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school, 3 = some training/college after high school, 4 = bachelor’s degree, 5 = graduate/professional studies).

Legal Status

Legal status was measured by immigration category. Participants were asked to report their current legal status in the United States. A total of 14 possible categories were provided, including temporary or permanent resident; tourist, student, temporary work visa; undocumented or expired visa; other. These categories were then recoded into a dichotomous variable of legal (1) or illegal (0) immigration status.

Religious Coping

The Ways of Religious Coping Scale (WORCS) was used to measure the extent to which participants used religious coping throughout their lives prior to immigration. This instrument is a 25-item questionnaire measuring internal and external religious coping cognitions and behaviors (Boudreaux et al., 1995). Items are divided into two subscales, internal/private and external/social religious coping. The internal subscale contains 15 items, including

I found peace by sharing my problems with God,

I prayed for strength,

I worked with God to solve problems,

I counted my blessings, and

I based life decisions on my religious beliefs.

The external subscale contains 10 items, including

I asked my religious leader for advice,

I got help from clergy,

I got involved with church/mosque/temple activities,

I talked to church/mosque/temple members, and

I donated time to a religious cause or activity.

In an effort to ensure pre-immigration religious coping was being reported by the participants, each person was read a script prior to scale administration emphasizing the following questions were related to how they handled stress before coming to the United States. The WORCS was initially validated with predominantly non-Latino white Christian college students (Boudreaux et al., 1995). Although the scale has been used with ethnic and racial minority groups, these samples have consisted largely of African-American respondents (Bishop, 2007; Boudreaux et al., 1995). As a means of making the WORCS more culturally sensitive to our sample, three items were expanded in an effort to broaden it from the Judeo-Christian perspective. The three items were expanded by adding “or other religious scripture” and “or other religious leader.”

Spanish translation of this measure was developed by the current authors. Specifically, the English version of the WORCS went through a process of (1) translation/back translation, (2) modified direct translation, (3) and checks for semantic and conceptual equivalence to ensure accurate conversion from English to Spanish. In an effort to account for any within-group variability, a review panel for the modified direct translation consisted of individuals from various Latino subgroups representative of the Miami-Dade county population. This process generated some slight modifications in question wording for a small number of items. Reliability estimates for the version of the WORCS used in the present study were favorable [internal scale (α = 0.95); external scale (α = 0.94)] and consistent with estimates yielded in past studies [internal scale (α = 0.95); external scale (α = 0.94)] (Boudreaux et al., 1995).

Given previous national survey results on the religious orientations of Latinos in the United States (Pew Research Center, 2007), use of the WORCS appears to be an appropriate measure. In regard to religious affiliation among Latinos in the United States: 68% are Catholic (68% of which are foreign born), 15% are Evangelical (55% foreign born), 5% are Mainline Protestant (35% foreign born), 3% Other Christians (57% foreign born), and 8% Secular (51% foreign born) (Pew Research Center, 2007). Therefore, this measure, along with the minimal alterations made to some items, appears to be in line with the overall religious perspectives of this population.

Acculturative Stress

The validated Spanish version of the immigration stress subscale of the Hispanic Stress Inventory Scale–Immigrant Version (Cervantes, Padilla, & Salgado de Snyder, 1990) was used to measure acculturative stress. This scale is a measure of psychosocial stress-event experiences for Latino immigrants. It has been widely used with this population (Ellison et al., 2009; Loury & Kulbok, 2007). The instrument is in a 5-point Likert scale format and the subscale used contains 18 questions. The participant reports whether or not he or she experienced a particular stressor. If the stressor was experienced, then a subsequent follow-up question is asked regarding the appraisal of how stressful that particular event was to the respondent (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). Example items are as follows: (1) “I felt guilty about leaving my family and friends in my home country”; (2) “Because of my poor English, it has been difficult for me to deal with day-to-day situations”; (3) “Because I am Latino, I have had difficulty finding the type of work I want.” Test-retest reliability coefficient for the Immigration Stress scale has been reported as .80 (p < .0001) with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to .85 (Cervantes et al., 1990). Given the very high correlation between frequency and appraisal of stress in the current sample (r = .91), the sum of the immigration stress frequency and immigration stress appraisal scores was used to measure overall acculturation stress.

Data Analytic Plan

Preliminary data analyses included calculating frequency distributions for all continuous variables to determine if they violated the assumption of normality. According to Kline (2005), variables were deemed non-normal if they yielded absolute skewness and kurtosis values greater than 3.0 and 8.0, respectively. Bivariate correlations were conducted involving all variables in the main analytic model to assess discriminant validity estimates among the predictor variables in the model for each sample.

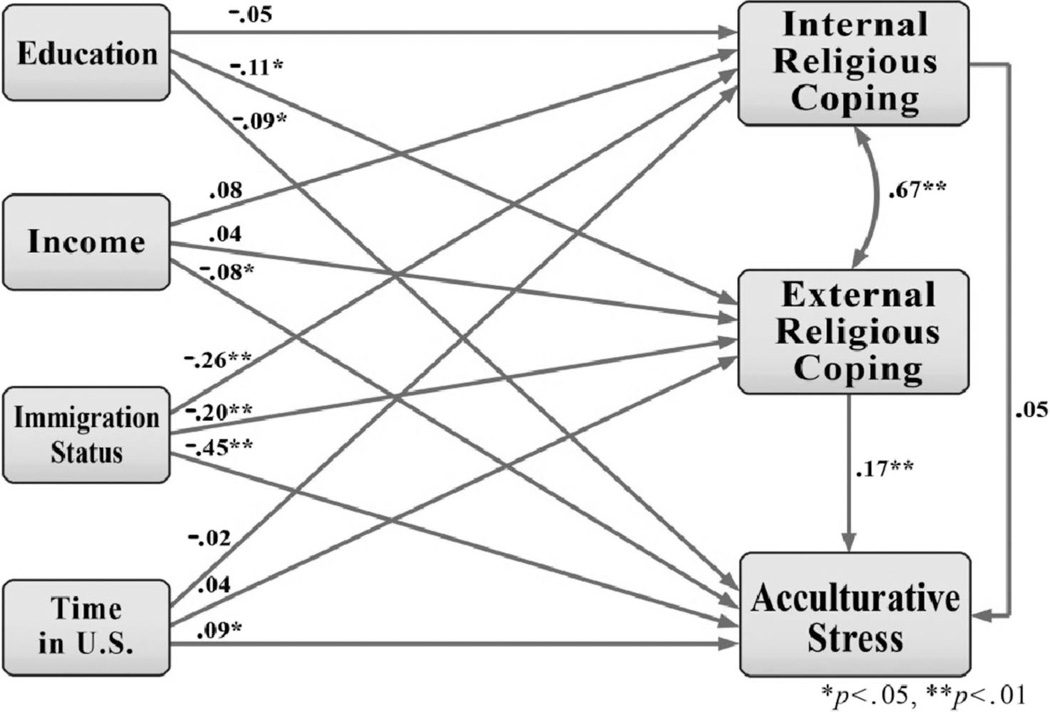

A path model analysis was conducted to examine the association between acculturative stress and internal/external religious coping while controlling for the potential influence of education, income, legal status, and time in the United States (see Figure 1). We first tested a saturated model using Multiple Indicators, Multiple Causes (MIMIC; Bollen, 1989) modeling to control for all hypothesized covariates. Through MIMIC modeling, the independent variables (internal and external religious coping) and the dependent variable (acculturative stress) were all regressed on the covariates (education, income, legal status, and time in the United-States) in the path model.

FIGURE 1.

A path model of acculturative stress.

The hypothesized model is just-identified or saturated. This type of fit occurs when the number of free parameters exactly equals the number of known values; therefore, it is a model with zero degrees of freedom. Thus path coefficients for the hypothesized model were examined, and insignificant paths were deleted one by one to seek the most parsimonious model that best fit the data. Model fit statistics and magnitude of associations between hypothesized variables for the subsequent models were compared in an effort to find the most parsimonious model that best fit the data (see Table 1). We evaluated the adequacy of the hypothesized and trimmed models using a variety of global fit indices including the following: the comparative fit index (CFI), for which values above .90 reflect adequate fit (Kline, 2005) and values above .95 represent excellent fit (Tomarken & Waller, 2005); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), for which values below .08 represent adequate fit (Quintana & Maxwell, 1999) and values below .05 represent excellent fit (Hancock & Freeman, 2001); and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), for which values below .08 represent adequate fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999) and values below .05 reflect excellent fit (Byrne, 1998).

TABLE 1.

Model Fit Comparisons of Trimmed Models (N = 527)

| Fit Indices | Saturated Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| CFI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .99 | .99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RMSEA | 0.00 | 0.00 | .02 | .05 | .03 | .01 | <.01 |

| SRMR | 0.00 | 0.00 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .02 | .02 |

Notes. Stepwise paths removed from each model as follows: Model 1 (internal religious coping → acculturative stress); Model 2 (education → internal religious coping); Model 3 (income → internal religious coping); Model 4 (income → external religious coping); Model 5 (time in the United States → internal religious coping); Model 6 (time in the United States → external religious coping).

FINDINGS

Preliminary Results

Frequency distributions for continuous variables determined that all continuous variables appeared to be normally distributed, except for income. The distribution of income scores was found to be positively skewed. Therefore, a square root transformation was conducted with participants’ income responses. This transformed value was used in subsequent analyses that require normally distributed variables. Descriptive statistics for the non-transformed income responses are reported in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Variables in Path Model

| Measures | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internal Religious Coping | 49.579 | 17.519 | 1 | .682** | .281** | −.263** | −.157** | .040 | .000 |

| 2. External Religious Coping | 21.034 | 10.878 | .682** | 1 | .321** | −.229** | −.173** | −.019 | .032 |

| 3. Acculturation Stress | 9.460 | 4.988 | .281** | .321** | 1 | −.544** | −.309** | −.108* | .108* |

| 4. Immigration Statusa | 0.694 | 0.461 | −.263** | −.229** | −.544** | 1 | .417** | .067 | −.044 |

| 5. Education Level | 2.567 | 1.059 | −.157** | −.173** | −.309** | .417** | 1 | .019 | .005 |

| 6. Income | 5265.11 | 5148.322 | .040 | −.019 | −.108* | .067 | .019 | 1 | −.006 |

| 7. Time in the U.S. | 6.741 | 3.110 | .000 | .032 | .108* | −.044 | .005 | −.006 | 1 |

Notes. Non-transformed mean and standard deviation values for income are presented

0 = illegal immigrant 1 = legal immigrant

p < .01.

Path Model

A bivariate correlation matrix, including means and standard deviations for variables involved in the path model, is presented in Table 2. Results from the hypothesized path model are shown in Figure 1. As expected, the path model controlling for all hypothesized covariates provided a just-identified or saturated model fit to the data, CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00.

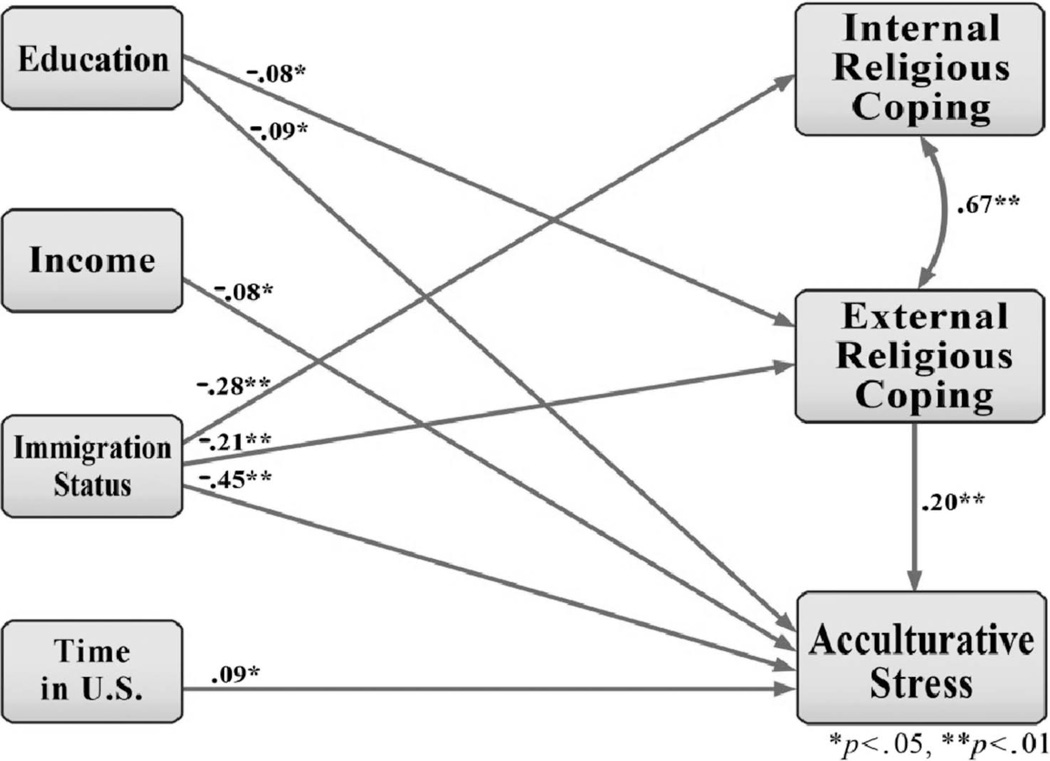

Next, we examined path coefficients for the hypothesized model and removed insignificant paths one at a time to find the most parsimonious model. Table 1 presents fit index comparisons between the hypothesized and alternative models, and lists each path that was removed in each model. The final trimmed model (Model 6) with all insignificant paths removed is presented in Figure 2. The final trimmed model indicated good model fit (CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .003, SRMR = .02). None of the significant (p < .05) path coefficients in the saturated model were impacted by trimming. All path coefficients were statistically significant before trimming and remained statistically significant after trimming.

FIGURE 2.

Final trimmed path model of acculturative stress.

Results from the final trimmed model were interpreted because they represented the most parsimonious model. Predictor variables (internal and external religious coping) and covariates (education, income, legal status, and time in the United States) in the final model accounted for 36% of variability in acculturative stress (p < .001). After controlling for participant covariates, high rates of pre-immigration external religious coping were associated with high levels of post-immigration acculturative stress. Participants with lower levels of education also reported higher rates of external religious coping. Undocumented legal status was associated with more post-immigration acculturative stress, and more pre-immigration internal and external religious coping. Lower levels of education and income were associated with more acculturative stress. Longer length of time in the United States was also associated with higher rates of acculturative stress. Finally, participants who reported more internal religious coping also reported high levels of external religious coping.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the association between pre-immigration religious coping and post-immigration acculturative stress among recent Latino immigrants. Findings indicated that recent Latino immigrants who used higher levels of pre-immigration external religious coping reported higher levels of post-immigration acculturative stress. Results also suggested that along with experiencing higher rates of acculturative stress, undocumented immigrants used more pre-immigration internal as well as external religious coping in comparison to their documented counterparts. Latino immigrants reporting lower levels of income and education also suffer from more acculturative stress than more affluent and educated immigrants. Acculturative stress also appeared to escalate as time in the United States increased.

Extant research has found religious coping to have protective effects on the health of Latinos (Hovey & Magaña, 2000; Finch & Vega, 2003; Coon et al., 2004). In contrast, the present results suggest that the use of pre-immigration external coping was associated with higher levels of acculturative stress. These findings may be due in part to the uniqueness of the current sample. Unlike previous studies, which have investigated associations between post-immigration religious behaviors and acculturative stress (Finch & Vega, 2003; Ellison et al., 2009), this study was apparently the first to investigate the pre-immigration religious coping resources that recent Latino immigrants bring with them from their country of origin. External religious coping primarily involves social support from a religious community. It may be that a dramatic loss of these valuable resources, soon after immigration, could make recent immigrants more vulnerable to experiencing acculturative stress. Hence, those immigrants who have used the church or religious leaders as a means of coping in the past may find themselves at a loss when those resources are no longer readily available to them in their host country. This potential explanation falls in line with past studies which have found acculturative stress to be lower among immigrants who establish and maintain support systems such as those found in church settings (Garcia, 2005).

Another explanation for religious coping and acculturative stress being positively related in the present study involves a religious orienting system known as negative religious coping. According to Pargament (2002b), negative religious coping styles emphasize passive or deferential responses to stress, where difficulties are viewed as punishment or abandonment from a higher being (God). The literature has linked this form of religious coping to feelings of guilt, shame, and overall poor mental health outcomes (Chatters, 2000). Studies have found individuals who use these coping styles tend to view the world as threatening, express a less secure relationship with a higher power, and demonstrate a sense of spiritual struggle (Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998).

The utilization of negative religious coping has demonstrated significant mental health implications. Such coping styles may negatively impact mental health by fostering feelings of guilt and shame; eroding feelings of competence, worth, and hopefulness; and distracting persons from more productive coping responses (Pargament, 2002b). Psychologically, these coping styles have been associated with increased rates in feelings of shame and guilt and anxiety, higher rates of depression, lower quality of life, and decreased sociability (Chatters, 2000). It may be possible that negative religious coping styles were at play in those individuals who demonstrated higher rates of acculturative stress in the current study. Future research with assessment tools that specifically measure negative religious coping styles, such as the Brief RCOPE (Pargament et al., 1998), are necessary in order to adequately decipher these effects.

Furthermore, no associations were found between pre-immigration internal religious coping and post-immigration acculturative stress. In contrast to external religious coping, internal religious coping is primarily a cognitive and private coping strategy involving prayer and cognitive reframing of a stressful event. It may be that this reframing and reevaluation, thought to be the mechanism by which internal religious coping is beneficial, are not fully captured by the internal religious coping scale. That is, reframing and reevaluation of the meaning of a stressful situation could be mechanisms to moderate stress, yet the scale used for the present study may not directly measure these mechanisms. In this case, the internal behaviors measured by the current study’s scale may not be linked with acculturative stress; however, other internal religious coping behaviors could potentially be associated with it. As previously mentioned, future investigations may benefit from the use of other religious coping scales, such as the Brief RCOPE, which measures other aspects of religious coping (i.e., positive and negative religious coping) that may be utilized in this population.

Consistent with past studies (Finch & Vega, 2003), undocumented immigrants experienced higher levels of acculturative stress. Although the effects were small, Latino immigrants (both documented and undocumented) with lower levels of income and education reported higher rates of acculturative stress. Latino immigrants with increased time in the United States also reported higher rates of acculturative stress. It should be noted that time in the United States ranged from 1 to 12 months in the present sample. These results are consistent with past research that has found acculturative stress to be at its highest levels during the first two years of immigration (Gil & Vega, 1996). In addition, there is ample literature documenting fear of deportation and strained economic circumstances as being longstanding sources of stress for Latino immigrants (Cabassa, 2003; Caplan, 2007; Moyerman & Forman, 1992; William & Berry, 1991; Yakushko, Watson, & Thompson, 2008). Findings from the current study are important, as acculturative stress has been found to influence health outcomes among Latinos (Finch & Vega, 2003). As such, acculturative stress is a factor that may influence health disparities among recently arrived Latinos. Future research is needed not only to understand the role that acculturative stress plays in health disparities affecting recent Latino immigrants, but also to develop interventions that aim to alleviate this stress. Particularly essential are interventions to reduce stress-related health disparities among those who appear to be most susceptible to this form of stress, namely undocumented and low socioeconomic status Latino immigrants.

Implications for Social Work

The social work profession recognizes immigration as a complex social, cultural, and political process (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2010). Social workers have historically been instrumental in assisting immigrants’ transition into American society. Amid the current political context of U.S. immigration policy and as the number of Latinos residing in the United States grows, the need to assist these individuals in making smooth transitions into American society is increasingly imperative. Religion represents a valuable cultural resource for many Latino immigrants who are struggling with the loss of a homeland and separation from family and friends. As social workers, it is critical to evaluate to what degree these resources may be accessed as a means of assisting immigrants in coping with the strains of the acculturation process.

Social work practice recommendations with individuals and families include greater attention to religiosity as a Latino cultural value in the service delivery process. As such, social workers should enhance their skills in navigating religious and/or spiritual issues within the clinical process. Based on Miller’s (1999) recommendation this may include the following:

an openness and willingness to understand the client’s religion/spirituality as it relates to issues of mental health;

some familiarity with culturally related values, beliefs, and practices that are common among the client populations that are likely to be served,

comfort in asking and talking about religious/spiritual issues with clients, and

a willingness to seek information from appropriate professionals and coordinate care concerning clients’ religious/spiritual traditions.

Service delivery implications of the current findings include the possible benefits of linking recent immigrants who have used external religious coping resources in their country of origin to similar religious centers in the host country. These resources may provide Latino immigrants with social support, which could prove to have a protective influence against acculturative stress along with all of its negative outcomes (Finch & Vega, 2003; Vega & Amaro, 1994). Furthermore, these centers of worship may provide familiarity to Latino immigrants entering into a new culture and environment as well as a means to accessing tangible services such as counseling, legal aid, and English and Spanish literacy programs. Religious centers may be viewed as a safe haven for immigrants who find themselves struggling to adjust to a new society with a different language and customs (Pew Hispanic Center, 2009). Social workers should assess recent Latino immigrants’ past and present social and cultural resources as well as coping strategies, and facilitate connections to religious resources if and when appropriate. Future research directions should also include investigating how linking recent Latino immigrants to such resources affects their levels of acculturative stress.

On a community level, fostering effective partnerships between the social work and religious communities may lead to beneficial physical and mental health outcomes among Latino immigrants. Social workers and religious leaders may be able to effectively work together in mediating the stressors involved in the acculturation process of recent Latino immigrants. This can take the form of interdisciplinary teams working together with religious community leaders in capacity building among centers of worship in immigrant-receiving communities. As such, these partnerships can lead to the development of faith-based outreach teams and pastoral counseling programs.

Current policies can make it difficult to deliver effective services to immigrants. Social workers should be informed about current immigration policies and advocate for fair and just immigration laws. Social workers can also help ensure that current policies which facilitate effective service delivery among Latino immigrants are adequately employed. For instance, the Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health provides national guidelines for the provision of culturally sensitive care (Hoffman, 2011). As such, CLAS encourages providers to become familiar with and integrate cultural and spiritual beliefs and practices into treatment plans when applicable. When working with recent Latino immigrants, issues of cultural competency can be particularly important. Advocating that these principles be implemented at an optimum capacity can lead to culturally sensitive practice. The ability of social workers to put CLAS standards into effect by offering culturally sensitive services that take into account cultural values and beliefs can likely have a beneficial impact on the quality of services provided to recent Latino immigrants.

Furthermore, broader investigations into the use of negative religious coping as a whole among this population are needed. Future research on religious coping styles among Latinos should include studies that expand scientific understanding of the function and effects of negative religious coping among this population. Gaining better insight into these coping mechanisms would provide valuable insight into targeting cognitions and behaviors that may need to be addressed when providing mental health prevention and intervention services to Latino immigrants.

There is also an existing demand to better understand the distinct acculturative stressors experienced by Latino immigrants across a variety of receiving communities. There may be unique acculturative stressors across new and well-established receiving communities (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). Acculturative stress studies with Latino immigrants have predominantly been conducted in areas of the United States with high Latino immigrant populations (Finch & Vega, 2003; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007). There is a notable shortage of research for Latinos in new/monocultural receiving communities. However, recent census data indicate that Latino populations are undoubtedly rapidly growing in traditionally non-Latino states such as North Carolina and Georgia (U.S. Census, 2011c). The immigration experience of Latinos into these states may be plagued with increased obstacles and struggles related to the acculturation process. This is predominantly due to the lack of available supports, unavailability of culturally or linguistically congruent services, and discrimination by receiving communities unfamiliar with the Latino population (e.g., Bender, Clawson, Harlan, & Lopez, 2004; Prado, Szapocznik, Maldonado-Molina, Schwartz, & Pantin, 2008). Gaining knowledge in this area could lead to enhanced theoretical models of acculturative stress that take into account the context of the receiving community. This knowledge can also lead to culturally based intervention work in areas of the United States where Latinos are newly immigrating, proving to be especially valuable in ameliorating the acculturative stress of recent Latino immigrants in these communities.

Limitations

The present results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The most evident limitation is the use of a sample of convenience. The nature of the sample consisted partially of a hidden population—undocumented immigrants. Therefore, the use of respondent-driven sampling, a method that has been widely successful in recruiting hidden populations, was implemented. Given that this population is difficult to access, this study provided a unique opportunity to examine this understudied group. Second, the use of self-report measures makes the design susceptible to socially desirable responses. Care was taken, however, to use psychometrically appropriate measures and include experienced Latino interviewers who were extensively trained in culturally appropriate interviewing techniques. Cultural adaptations in research with Latinos, such as employing culturally informed interviewers and devising well-adapted questionnaires, have been found to increase participant satisfaction and provide more accurate data (De La Rosa, Rahill, Rojas, & Pinto, 2007). The investigation also utilized self-report measures of retrospective religious coping styles prior to immigration, making the responses susceptible to errors in recollection. Furthermore, participants’ recollection of pre-immigration religious coping behaviors may have been influenced by the experience of present acculturative stress. Third, the expansion of three items of the WORCS in an effort to make it more culturally sensitive to our sample could have potentially altered the meaning of the items. Fourth, the study was conducted with a fairly young sample (ages 18–34). As such, these findings cannot be generalized to other Latino age groups as generational differences have been found to play a role in frequency and quality of religious coping styles (Koenig, 2006). Fifth, it should be noted that although there was a small (.20) significant relationship between external religious coping and acculturative stress, external religious coping only explained a limited amount of variance in acculturative stress. Future research is needed to elucidate additional determinants of variance in stress among Latino immigrants. Finally, the research design is cross-sectional, rather than longitudinal, not allowing for examination of causal inferences and changes in behavior patterns over time. Future longitudinal studies are needed to continue to shed light on the relationship between religious coping and acculturative stress among Latino immigrants.

CONCLUSION

The primary contributions of this study to the literature appear to be at least threefold. First, the use of an ethnically diverse sample of recent Latino immigrants is an important advance in research with ethnic minority populations. The rise of immigration to the United States from a wide array of Latin American countries makes gaining better insight and understanding of this population a critically important social welfare concern. Second, the investigation focuses on the largely understudied construct of religious coping among Latinos. Religion is a central cultural value among Latinos, thus it is important to expand our awareness as to how its use affects the mental and physical well-being of this population. Finally, the present study contributes to the limited knowledge on how pre-immigration factors affect the stress levels of Latino immigrants. Gaining a better understanding of the stress and coping processes in the lives of recent immigrants can help inform public policy and tailor prevention and intervention programs through targeting the specific needs of this population. Moreover, this knowledge can assist social workers in adequately empowering Latino immigrants in fully becoming healthy members of their host societies (Yakushko et al., 2008).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by award number P20MD002288 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and a predoctoral fellowship award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), award number 1F31 DA029400-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

REFERENCES

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Vasquez E, Echeverria SE. En las Manos de Dios [in God’s Hands]: Religious and other forms of coping among Latinos with arthritis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:91–102. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:461–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender DE, Clawson M, Harlan C, Lopez R. Improving access for Latino immigrants: Evaluation of language training adapted to the needs of health professionals. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2004;6:197–209. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000045257.83419.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46:5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. Adult religious education as transformative learning: The use of religious coping strategies as a response to stress. Dissertation Abstract International Section A. Humanities and Social Sciences. 2007;68:6–6A. 2278. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equation with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux E, Catz S, Ryan L, Amaral-Melendez A, Brantley PJ. The ways of religious coping scale: Reliability, validity, and scale development. Assessment. 1995;2:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan S. Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice. 2007;8:93–106. doi: 10.1177/1527154407301751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. The Hispanic stress inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1990;3:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM. Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW, Rupert M, Solano N, Mausbach B, Kraemar H, Argulles T, Gallagher-Thompson D. Well-being, appraisal, and coping in Latina and Caucasian female dementia caregivers: Findings from the REACH study. Aging and Mental Health. 2004;8:330–345. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001709683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Torres Stone RA, McGinely M, Raffaelli M, Carlo G. Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:347–355. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, Babino R, Rosario A, Valiente N, Aijaz N. Challenges and strategies in recruiting, interviewing, & retaining recent Latino immigrants in substance abuse and HIV epidemiologic studies. American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, Rahill GJ, Rojas P, Pinto E. Cultural adaptations in data collections: Field experiences. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6:163–180. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman D, Paulino A. Thinking beyond the United States borders. Journal of Immigration and Refugee Services. 2004;291:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M, O’Brien K. Psychological health and meaning in life. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009;31:204–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Finch BK, Ryan DN, Salinas JJ. Religious involvement and depressive symptoms among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:171–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory and future directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BF, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C. Buscando trabajo: Social networking among immigrants from Mexico to the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Vega WA. Two different worlds: Acculturation stress and adaptation among Cuban and Nicaraguan families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13:435–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Freeman MJ. Power and sample size for the root mean square error of approximation test of not close fit in structural equation modeling. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:741–758. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2008;1:3–17. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman NA. The requirements for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. Journal of Nursing Law. 2011;14:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CI, Lewellyn LA, Rathweg MJ. Exploring religion-health mediators among African American parishioners. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:511–527. doi: 10.1177/1359105305053416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, Magana C. Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican farm workers in the Midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2000;2:119–131. doi: 10.1023/A:1009556802759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality and aging. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10:1–3. doi: 10.1080/13607860500308132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Hayes Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loury S, Kulbok P. Correlates of alcohol and tobacco use among Mexican immigrants in rural North Carolina. Family Community Health. 2007;30:247–256. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000277767.00526.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña A, Clark NM. Examining a paradox: Does religiosity contribute to positive birth outcomes in Mexican American populations. Health Education & Behavior. 1995;22:96–109. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Coon DW, Cardenas V, Thompson LW. Religious coping among Caucasian and Latina dementia caregivers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2003;9:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia OL, McCarthy CJ. Acculturative stress, depression, and anxiety in migrant farmwork college students of Mexican heritage. International Journal of Stress Management. 2010;17:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar C. Religion and immigration in comparative perspective: Catholic and Evangelical Salvadorans in San Francisco, Washington DC, and Phoenix. Sociology of Religion. 2003;64:21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Integrating spirituality into treatment: Resources for practitioners. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Molock S, Purl R, Matlin S, Barksdale C. Relationship between religious coping and suicidal behaviors among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:366–389. doi: 10.1177/0095798406290466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyerman DR, Forman BD. Acculturation and adjustment: A meta-analytic study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1992;14:163–200. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. Immigration and refugee resettlement. 2010 Aug; Retrieved from http://www.naswdc.org/pubs/news/2006/02/desilva.asp.

- Nee V, Alba R. Toward a definition. In: Jacoby T, editor. Reinventing the melting pot: The new immigrants and what it means to be American. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2004. pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Is religion nothing but …? Explaining religion versus explaining religion away. Psychological Inquiry. 2002a;13:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The bitter and sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Psychological Inquiry. 2002b;13:168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D. Trends in unauthorized immigration: Undocumented inflow now trails legal inflow. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. U.S. population projections 2005–2050. 2009 Retrieved from http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report-php?RepostID=85.

- Pew Research Center. Changing faiths: Latinos and the transformation of American religion. 2007 Retrieved from http://pewforum.org/uploadedfiles/Topics/Demographics/Race/hispanics-religion-07.pdf.

- Plante TG, Manuel G, Menendez A, Marcotte D. Coping with stress among Salvadoran immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Best S, Metzler T, Marmar C. Why are Hispanics at greater risk for PTSD? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11(2):144–161. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Szapocznik J, Maldonado-Molina MM, Schwartz S, Pantin H. Drug use/abuse prevalence, etiology, prevention, and treatment in Hispanic adolescents: A cultural perspective. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Maxwell SE. Implication of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist. 1999;27:485–527. [Google Scholar]

- Reid TL, Smalls C. Stress, spirituality, and health promoting behaviors among African American college students. Western Journal of Black Studies. 2004;28:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2003;34:193–240. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger J, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga B, Jarvis LH. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behavior, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen P, Merrill R. The association between religion and acculturation in Utah Mexican immigrants. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2011;14:561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Obiri O. Do religious coping styles moderate or mediate the external and internal racism-distress link? The Counseling Psychologist. 2011;39:438–462. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tix AP, Frazier PA. The use of religious coping during stressful life events: Main effects, moderation, and mediation. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:411–422. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:31–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census. The Hispanic population: 2010 Census briefs. 2011a Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- United States Census. Decennial Census 2000 and 2010. Miami, FL: Miami Dade County Department of Planning and Zoning; 2011b. Retrieved from http://www.miamidade.gov/redistricting/library/district-demographics.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census. The newly arrived foreign born population of the United States: 2010. American Community Survey Briefs; 2011c. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acsbr10-16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Valle R. Culture-fair behavioral symptom differential assessment and intervention in dementing illness. Alzheimer Disease & Associates Disorders. 1994;8(Suppl. 3):21–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Amaro H. Latino outlook: Good health, uncertain prognosis. Annual Review in Public Health. 1994;15:39–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace KA, Bergeman CS. Spirituality and religiosity in a sample of African American elders: A life story approach. Journal of Adult Development. 2002;9:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- William CL, Berry JW. Primary prevention of acculturative stress among refugees: Application of psychological theory and practice. American Psychologist. 1991;46:632–641. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.6.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakushko O, Watson M, Thompson S. Stress and coping in the lives of recent immigrants and refugees: Consideration for counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling. 2008;30:167–178. [Google Scholar]