Abstract

Paraganglioma is a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm observed in patients of all ages, with an estimated incidence of 3/1,000,000 population. It has long been recognized that some cases are familial. The majority of these tumors are benign, and the only absolute criterion for malignancy is the presence of metastases at sites where chromaffin tissue is not usually found. Some tumors show gross local invasion and recurrence, which may indeed kill the patient, but this does not necessarily associate with metastatic potential. Here, we report a case of vertebral metastatic paraganglioma that occurred 19 months after the patient had undergone partial cystectomy for urinary bladder paraganglioma. We believe this to be a rarely reported bone metastasis of paraganglioma arising originally within the urinary bladder. In this report, we also provide a summary of the general characteristics of this disease, together with progress in diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

Keywords: Bone neoplasms, malignant paraganglioma, neuroendocrine peptide, neuroendocrine tumors, surgery, carcinoma

Paraganglioma (also known as extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma) is a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm observed in patients of all ages, with an estimated incidence of 3/1,000,000 population. It has long been recognized that some cases are familial. The majority of these tumors are benign, and the only absolute criterion for malignancy is the presence of metastases to sites where chromaffin tissue is not usually found[1]. We present here a case of malignant urinary bladder paraganglioma with bone metastasis after partial cystectomy. The patient was successfully treated with a second surgical excision. Based on a thorough review of the literature, we found that this case represents a seemingly rare occurrence of this disease. In this report, we describe the characteristics of this case in detail and review progress in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of paraganglioma.

Case Description

In September 2005, a 53-year-old woman complaining of odynuria over a week was admitted to the Department of Urinary Surgery at the Affiliated Zhongshan Hospital of Dalian University. The pain began as an odd sensation described as a pricking pain in the lower abdomen without radiating pain. This pricking pain happened suddenly, without any motivation or signs. There was no history of hematouria, pyuria, or low-back pain, and there was no precipitating trauma nor aggravating or alleviating factors.

The patient appeared healthy and had a blood pressure of 21.3/12.0 kPa (160/90 mmHg). In the following physical examination, there was no tenderness to palpation over the whole abdomen, nor were any other positive physical signs found. Abdominal sonography revealed a heteroplastic, hyperechoic mass in the right anterior wall of the urinary bladder, which was confirmed on subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan. The CT documented the presence of a hypervascularized mass approximately 4.7 cm in diameter with a homogeneous aspect.

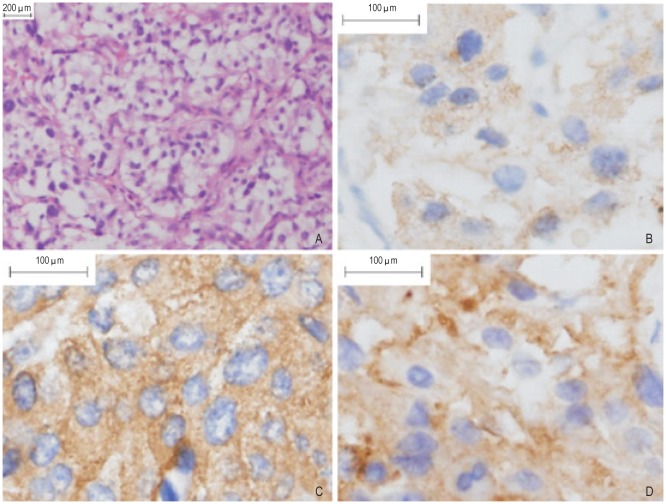

The patient underwent partial cystectomy for bladder tumor. During surgery, the tumor appeared as an intensely vascularized mass (6 cm × 5 cm × 4 cm) located in the right anterior wall of the urinary bladder. No apparent margin invasion and local metastasis were found, and these findings were confirmed by subsequent pathologic examination. The biopsy in the remaining proximal part of the urinary bladder revealed that there was no tumor tissue left. The tumor histology revealed an alveolar pattern with nests of neoplastic cells surrounded by vascularized connective tissue septa, and no vascular or capsular invasion was found. The tumor was composed of three cell types: epithelioid cells, surrounding spindle-shaped sustentacular cells, and scattered ganglion cells. The epithelioid cells were arranged in nests. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase, and synaptophysin (Figure 1) and negative for cytokeratin. No signs of necrosis were found. Based on the pathologic findings, the definite diagnosis was paraganglioma. The patient's postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged on the eighth day after surgery. No further therapy was thought to be indicated.

Figure 1. Microscopic appearance of urinary bladder paraganglioma.

Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with antibody or blocking buffer alone, as a negative control, using the avidin-biotin complex method, and signal was developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Positive staining for markers in the cytoplasm and stroma was indicated in brown. A, hematoxylin-eosin staining shows that epithelioid cells were arranged in nests in paraganglioma (100×). B, chromogranin A expression is positive in paraganglioma (400×). C, neurone-specific enolase expression is positive in paraganglioma (400×). D, synaptophysin expression is positive in paraganglioma (400×).

Follow-up at 1 year showed complete resolution of preoperative symptoms, and abdominal sonography revealed no evidence of local recurrence. However, at 19 months of follow-up, the patient came back to the hospital and reported a month-long history of increasing back pain radiating along the intercostal space. She got abrupt paralyzing numbness in both lower limbs as well. The patient reported that the pain was usually aggravated at night. She also reported a month-long history of night sweat and hectic fever. In the physical examination, there was apparent tenderness on palpation of the spinous process and the nearby area of the sixth and seventh thoracic vertebra. The measurement of muscle strength revealed grade 3/5 flexion at the hips and extension at the knees, and grade 4/5 dorsiflexion and plantar flexion at the ankles. Hypesthesia was present under the fourth lumbar nerve level in both lower limbs as well as in the saddle area.

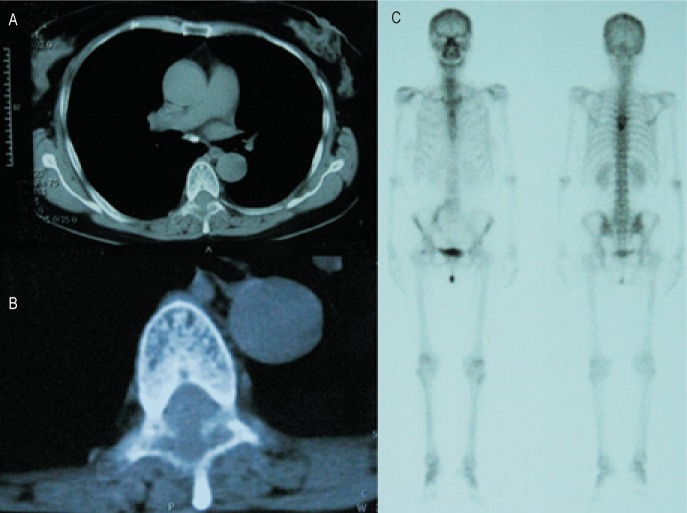

A thoracic CT scan showed bone damage with low density in the sixth thoracic vertebra, where there was a soft tissue mass protruding into the vertebral canal and compressing the spinal cord (Figures 2A, B). Total body Tc-99m bone scan revealed a well-circumscribed area of intense uptake in the same region (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. The radiological findings of the patient.

A thoracic CT scan shows bone damage in the sixth thoracic vertebra, where a soft tissue mass protrudes into the vertebral canal, compressing the spinal cord (A, B). Total body Tc-99m bone scan reveals a well-circumscribed area of intense uptake in the same region (C).

Because of the vertebral tumor, the patient underwent tumor excision together with allograft bone transplantation and spinal fusion. The surgery confirmed the tumor in the sixth thoracic vertebra. Pathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of vertebral metastasis of the malignant paraganglioma, which had the same histologic pattern and immunohistochemical findings as the paragangioma in her urinary bladder 19 months before. The patient's postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged on the 14th day after surgery. Follow-up at 1 year and 1.5 years showed complete resolution of preoperative symptoms and no local recurrence or metastasis according to CT scan and total body metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy.

Discussion and Conclusions

It is usually very difficult to clinically differentiate bladder paraganglioma from the overwhelmingly more common bladder urothelial carcinoma, but this rare tumor can be confirmed by pathologic examination. Microscopically, paragangliomas are composed of large, polyhedral, pleomorphic chromaffin cells that are usually arranged in nests. Histologically, paragangliomas are characterized by a honeycomb pattern in which well-circumscribed nests (Zellballen) of round-oval or giant multinucleated neoplastic cells with cytoplasmic catecholamine granules are surrounded by S-100–positive supratentorial cells. Pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and bizarre nuclear forms (which do not necessarily reflect a higher grade of malignancy) may also be seen. There are no standardized histologic criteria for differentiating malignant and benign paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Paragangliomas are considered malignant only when cells with neoplastic characteristics are found in areas in which paraganglionic tissue is normally absent. Moreover, tumors that contain a large number of aneuploid or tetraploid cells are more likely to recur[1],[2]. There are two types of paragangliomas: sympathetic and parasympathetic. The former arises from the sympathetic paraganglia that lie along the paravertebral and para-aortic axis in close relation to the sympathetic trunk, extending from near the superior cervical ganglion high in the neck to the abdomen and pelvis. These include the adrenal medulla and the organ of Zuckerkandl. A minority originate in tiny paraganglia lying in the connective tissue adjacent to pelvic organs. Parasympathetic paragangliomas are found in the head and neck close to vascular structures and branches of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves, and these include carotid body, aorticopulmonary, intravagal, and jugulotympanic tumors[3].

Paraganglioma cells are characterized by the presence of neuroendocrine markers, including neuron-specific enolase, S-100 protein, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, vimentin, PGP9.5, and CD56. Paragangliomas have multiple synthetic activities; however, in spite of tumor heterogeneity, chromogranin A and synaptophysin are the most common neuropeptides synthesized, as they are associated with the presence of neuroendocrine storage granules[4]. In the case reported here, we confirmed the presence of some of those markers in malignant paraganglioma. This suggests that immunophenotypic analysis could be useful in the diagnosis of this disease.

Biochemical measurements of urine/plasma catecholamines have proper sensitivity and specificity for detecting catecholamine-secreting functional paragangliomas. Among all tests studied, measurement of free metanephrines in the plasma was found to have the best predictive value for excluding or confirming a pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma[5]. For nonfunctional paragangliomas, which are a heterogeneous group of tumors, using a single test may not be reliable and a combination of tests may result in higher diagnostic accuracy. CT and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used as primary radiologic localization tools. These tests are sensitive and can identify tumors as small as 1 cm in diameter. Furthermore, scintigraphy with 131I-labeled MIBG (MIBG 131) is useful not only for noninvasive diagnosis of paragangliomas but also for palliative treatment in cases in which other types of treatment are unsuccessful[6]. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose, 11C-hydroxyephedrine, or 6-18F-fluorodopamine may help to identify conventionally undetectable tumors[7],[8].

Nevertheless, the clinical and histologic features predictive of paraganglioma malignancy are still poorly defined. The level of serum catecholamines does not necessarily associate with tumor malignancy. In a majority of past reports, immunohistochemistry has not been used to refine the diagnosis of malignant potential, though some malignant tumors may express fewer or different peptides than benign tumors. Although we discovered in our review that some of those markers, such as vimentin, may have potential value in differential diagnosis of malignant tumors[1],[3],[4],[7], further studies are needed to prove the value of those markers. S-100–positive sustentacular cells are often sparse in malignant tumors, although this is not 100% sensitive[1],[4]. The only absolute criterion for malignancy is the presence of metastases to sites where chromaffin tissue is not usually found. However, some other features of the tumor may indicate malignant characteristics, including recurrence, gross local invasion, vascular or capsular invasion, tumor necrosis, malignant histologic pattern, and cellularity[9]. Evidence also suggests that multifactorial scoring systems can help to histopathologically discriminate tumors that pose a significant risk of metastasis from those that do not. In 2002, Thompson[10] proposed the pheochromocytoma of adrenal scaled score (PASS) system, which scores multiple microscopic findings. A PASS of <4 accurately identified all histologically and clinically benign tumors, and a PASS of ≥4 correctly identified all tumors that were histologically malignant.

Surgical resection offers the only chance for a cure in these patients with paragangliomas and is associated with improved survival. Paragangliomas have a higher rate of malignancy and have been traditionally resected in an open operation, especially tumors with size greater than 8–10 cm and evidence of local invasion or recurrence[11]. In our previous study, tumor resection was performed via open operation in all 152 selected patients[12]. Laparoscopic resection can be performed if the paraganglioma is amenable to complete resection and exhibits no grossly malignant features at the time of surgery. For functional paragangliomas, preoperative pharmacologic therapy is necessary before surgical intervention. Adequate preoperative α-blockade and intravascular volume expansion is essential to decrease the complications of intraoperative hemodynamic effects caused by excess catecholamines[11]–[13]. For some malignant paragangliomas, especially those in which surgical extirpation is impossible, chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be used as therapeutic options. Such unresectable tumors may be treated with palliative chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, and vincristine, external beam radiotherapy for bony metastases, or 131I-labeled MIBG. The latter could also be used for symptom palliation in the late stage of the disease. These adjuvant therapies, together with surgical resection, may be the best curative option for patients with unresectable malignant paraganglioma, because this combined approach would target both the excisable portion of the tumor and any tissue that remains after surgery[14],[15].

For patients with benign tumors, most studies reported 5-year survival rates above 95%, with recurrences in less than 10% of patients[3],[6],[12]. The survival of patients with malignant tumous, however, is difficult to determine, because these patients are usually reported in single case studies rather than large, controlled, randomized studies. Nevertheless, the survival of patients with malignant paraganglioma is thought to be related to the familial circumstance, the stage of the disease at the diagnosis, the therapeutic methods, and the follow-up after surgery. However, more studies that focus on the neuroendocrine markers in paragangliomas, especially in the large sample analysis, are warranted in the future to determine these associations.

References

- 1.Tischler AS. Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1272–1284. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1272-PAEPU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonello M, Piazza M, Menegolo M, et al. Role of the genetic study in the management of carotid body tumor in paraganglioma syndrome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:517–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JA, Quan YD. Sporadic paraganglioma. World J Surg. 2008;32:683–687. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lori AE, Ricardo VL. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of endocrine tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2004;11:175–189. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000131824.77317.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuta N, Kiyota H, Yoshigoe F, et al. Diagnosis of pheo-chromocytoma using [123I]-compared with [131I]-metaiodoben- zylguanidine scintigraphy. Int J Urol. 1999;6:119–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.1999.06310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacek K, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS. Functional imaging of endocrine tumors: role of positron emission tomography. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:568–580. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilias I, Pacak K. Anatomical and functional imaging of metastatic pheochromocytoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:495–504. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.August C, August K, Schroeder S, et al. CGH and CD 44/MIB-1 immunohistochemistry are helpful to distinguish metastasized from nonmetastasized sporadic pheochromocytomas. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1119–1128. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson LD. Pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland scaled score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:551–566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang C, Bradley CL, John CC, et al. Paraganglioma of the urinary bladder. Cancer. 2000;88:844–852. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000215)88:4<844::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng N, Zhang WY, Wu XT. Clinicopathological analysis of paraganglioma with literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3003–3008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thapar PM, Dalvi AN, Kamble RS, et al. Laparoscopic Transmesocolic excision of paraganglioma in the organ of Zuckerkandl. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2006;16:620–622. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safford SD, Coleman E, Gockerman J, et al. Iodine-131 metaiodo-benzylguanidine is an effective treatment for malignant pheochro- mocytoma and paraganglioma. Surgery. 2003;134:956–962. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitiakoudis M, Koukourakis M, Tsaroucha A, et al. Malignant retroperitoneal paraganglioma treated with concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2004;16:580–581. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]