Abstract

Pituitary metastasis from renal cell carcinoma is rare and has never been reported for renal cell carcinoma primarily treated with sorafenib. Herein, we present a case of an advanced clear-cell renal cell carcinoma in which pituitary metastasis progressed but extracerebral metastases showed partial response to sorafenib treatment.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, pituitary metastasis, sorafenib

Metastasis to the pituitary gland is an infrequent complication typically seen in elderly patients with diffuse malignant disease. In large autopsy studies, the incidence of pituitary metastasis was 1% to 4% in all cancer patients[1] and occurred most commonly in patients with neoplasms of the breast (49.8%), lung (20.2%), and gastrointestinal tract (6.4%)[2]. Pituitary metastasis from renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is rare, and the response of pituitary metastasis from RCC to new targeted drugs like sorafenib (Nexavar, BAY 43-9006) and sunitinib is unknown. Here, we describe a case of pituitary and extracerebral metastases from clear-cell RCC treated with sorafenib.

Case Report

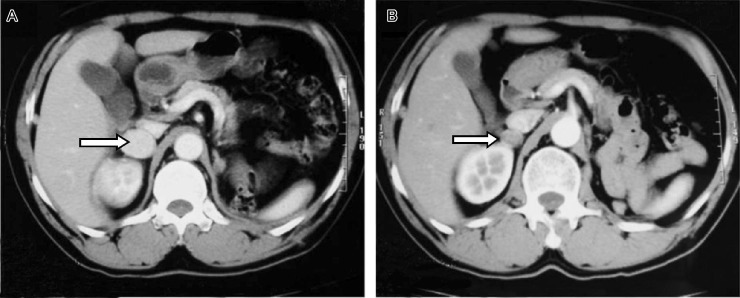

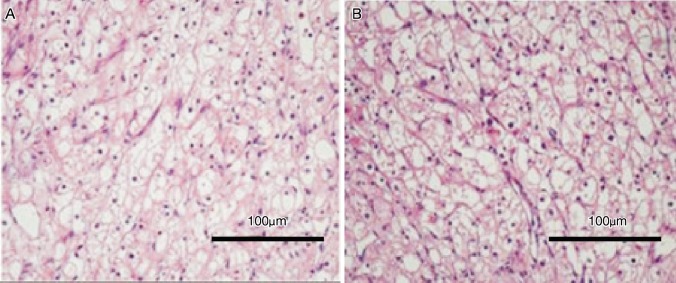

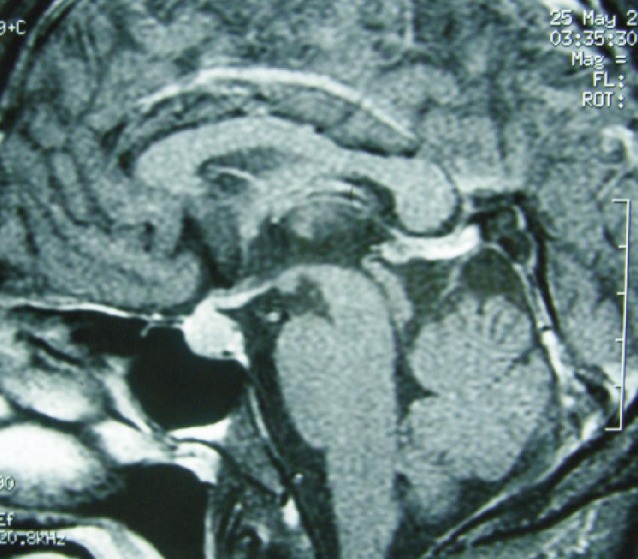

A 51-year-old man originally presented with an asymptomatic tumor in his left kidney revealed by a routine abdomen ultrasonography in October 2005. His medical history was unremarkable except for 11 years of hypertension, which was controlled well with calcium antagonist. Radical nephrectomy was then undertaken and pathologic examination showed clear-cell RCC (Figure 1), staged T3N0M0. He underwent cytokine therapy with interleukin-2 for 3 months after surgery and felt well. However, in subsequent routine examinations, a computed tomographic (CT) scan suggested metastases to bilateral adrenal glands (Figure 2), retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and multiple bones. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was then performed and showed diffuse enlargement of the pituitary gland (Figure 3), which was considered pituitary nonfunctional adenoma or pituitary hyperplasia. In June 2006, the patient began treatment with sorafenib, taking 400 mg orally twice daily. Treatment was interrupted in the third week and then between the 12th and 16th week because of grade 3 hand-foot reaction syndrome and aggravated hypertension accompanied by grade 2 alopecia and arthralgia according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0. After the interruption, the dose of sorafenib was reduced to 400 mg orally once daily. After 8 weeks of sorafenib treatment, CT scan of the abdomen showed tumor shrinkage and partial response (Figure 2), which was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). This partial response status was verified 4 weeks later. In the 20th week, the patient felt rapid deterioration with blurry vision. Physical examination revealed left-sided temporal hemianopia, ptosis of the left upper lid, left sixth nerve palsy, and diplopia. Hormonal evaluation suggested adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) deficiency and hyperprolactinemia (Table 1). Additional brain CT scan showed a Sellar mass with suprasellar extension compressing the optic chiasm and eroding the Sellar base (Figure 4). In November 2006, transsphenoidal surgery revealed a vascular tumor that invaded the Sellar base and the normal pituitary gland. Only biopsy was performed, and pathologic examination showed clear-cell carcinoma consistent with pituitary metastasis of RCC (Figure 1B). Treatment with sorafenib was stopped when disease progression was detected. The patient underwent conformal radiotherapy to the pituitary tumor bed at a dose of 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions and then 600 cGy in 3 fractions. After radiotherapy, his visual acuity and visual field recovered partially. One month later, multiple bilateral lung nodules were suggested by chest CT scan. In September 2007, the patient died due to dyspnea. Survival time was 23 months from nephrectomy, 16 months from initial diagnosis of metastases and use of sorafenib, and 9 months from diagnosis of symptomatic pituitary metastasis.

Figure 1. Both histologic images (HE staining) of the primary tumor in kidney (A) and the metastatic tumor in the pituitary (B) showed clear-cell renal carcinoma.

Figure 2. Metastasis in the patient's right adrenal gland dwindled notably after sorafenib treatment.

A, computed tomography before sorafenib treatment. B, computed tomography after 8 weeks of sorafenib treatment.

Figure 3. Magnetic resonance image shows diffuse enlargement of the pituitary gland before treatment with sorafenib.

Table 1. Results of hormonal evaluation in the patient with pituitary metastasis from renal cell carcinoma.

| Hormone | Normal range | The current case |

| TSH (mU/L) | 0.3–5.5 | 0.36 |

| Free T4 (ng/L) | 0.089–0.200 | 0.075 |

| Free T3 (ng/L) | 2.0–4.1 | 2.63 |

| ACTH (ng/L) | 7.5–58.0 | 2.2 |

| GF (µg/L) | <10 | 0.86 |

| Prolactin (µg/mL) | 2.1–17.7 | 66.31 |

TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; T4, tetraiodothyronine; T3, triiodothyronine; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; GF, growth factor.

Figure 4. The lesion in the patient's pituitary enlarged notably after 20 weeks of sorafenib treatment.

Computed tomography shows a 2.0-cm Sellar mass with suprasellar extension compressing the optic chiasm and eroding the Sellar base.

Discussion

Symptomatic metastases to the pituitary from RCC are rare. To our knowledge, only 28 cases have been reported in the literatures, among which only 3 patients received targeted drugs including sorafenib and sunitinib after pituitary surgery and/or radiotherapy[3],[4]. Using targeted drugs as the initial course of treatment in patients with pituitary metastasis from RCC has never been reported before.

In the case reported here, the patient was initially asymptomatic, and brain MRI was performed when metastases to his extracerebral sites were identified according to the previous recommendations[5]. Diffuse enlargement of the pituitary gland was mistaken as pituitary nonfunctional adenoma or pituitary hyperplasia, as pituitary adenoma has much higher incidence than pituitary metastasis, even in patients with known systemic malignancy. In clinical terms, preoperative diagnosis of metastases to the pituitary is difficult[6]. The rapidity of symptom development and rapidly growing sellar tumor may contribute to the diagnosis of metastases to the pituitary from RCC.

There is limited information on the proper treatment for the metastases to the pituitary from RCC. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommended traditional surgery, stereotactic radiotherapy, and whole brain irradiation in RCC patients with brain metastases[7]. As the lesions of pituitary metastases from RCC tend to be firm, diffuse, invasive, vascular, and hemorrhagic, total resection is considered impossible[6]. However, local radiotherapy improves symptom control and survival, but long-term local control has been poor[8].

Targeted therapy is now widely used in metastatic RCC. As patients with brain metastases from RCC were frequently excluded from most clinical trials, their effects on RCC patients with brain metastases are unclear. Some small clinical trials and cases were reported, but these results are controversial.

In the current case, extracerebral lesions showed partial response during sorafenib treatment, while pituitary metastasis progressed rapidly. This suggests a difference in pharmacokinetic behavior and less activity of sorafenib within the brain. Data from an expanded access trial, including 321 patients with brain metastases out of 4,371 patients with RCC, revealed that sunitinib was effective and safe in subgroups of patients with brain metastases[8]. However, no data was provided on prior central nervous system radiation. Helgason et al.[9] reported that sunitinib does not influence the incidence of brain metastases. We propose that, as sole treatments, targeted drugs like sorafenib are inadequate for control of brain metastases, including metastases to the pituitary from RCC.

This case illustrates two important points. First, metastases to the pituitary from RCC is extremely rare, but it should be considered when rapidly developing symptoms and a rapidly growing sellar tumor occur. Also, asymptomatic abnormality in pituitary images should be monitored regularly to diagnose metastases to the pituitary at an early stage. Second, patients diagnosed with metastases to the pituitary should receive local, pituitary-specific treatment, including surgery or radiotherapy, before initiation of systematic treatment. Primary treatment with targeted drugs, like sorafenib, might not be adequate for control of metastases to the pituitary from RCC. Studies of far more aggressive treatment strategies, like new drugs for new targets, are needed.

References

- 1.Kovacs K. Metastatic cancer of the pituitary gland. Oncology. 1973;27:533–542. doi: 10.1159/000224763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick PC, Post KD, Kandji AD, et al. et al. Metastatic carcinoma to the pituitary gland. Br J Neurosurg. 1989;3:71–79. doi: 10.3109/02688698909001028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamoshima Y, Terasaka S, Hamauchi S, et al. et al. A case of symptomatic pituitary metastases from renal cell carcinoma. No Shinkei Geka. 2011;39:999–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopan T, Toms SA, Prayson RA, et al. et al. Symptomatic pituitary metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Pituitary. 2007;10:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s11102-007-0047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shuch B, La Rochelle JC, Klatte T, et al. et al. Brain metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: presentation, recurrence, and survival. Cancer. 2008;113:1641–1648. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komninos J, Vlassopoulou V, Protopapa D, et al. et al. Tumors metastatic to the pituitary gland: case report and literature review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:574–580. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012. Kidney cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gore ME, Hariharan S, Porta C, et al. et al. Sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with brain metastases. Cancer. 2011;117:501–509. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helgason HH, Mallo HA, Droogendijk H, et al. et al. Brain metastases in patients with renal cell cancer receiving new targeted treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:152–154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]