Abstract

This study examined processes of change associated with the positive preschool and kindergarten outcomes of children who received the Head Start REDI intervention, compared to “usual practice” Head Start. In a large-scale randomized-controlled trial (N = 356 children, 42% African American or Latino, all from low-income families), this study tests the logic model that improving preschool social-emotional skills (e.g., emotion understanding, social problem solving, and positive social behavior) as well as language/emergent literacy skills will promote cross-domain academic and behavioral adjustment after children transition into kindergarten. Validating this logic model, the present study finds that intervention effects on three important kindergarten outcomes (e.g., reading achievement, learning engagement, and positive social behavior) were mediated by preschool gains in the proximal social-emotional and language/emergent literacy skills targeted by the REDI intervention. Importantly, preschool gains in social-emotional skills made unique contributions to kindergarten outcomes in reading achievement and learning engagement, even after accounting for the concurrent preschool gains in vocabulary and emergent literacy skills. These findings highlight the importance of fostering at-risk children's social-emotional skills during preschool as a means of promoting school readiness.

The REDI (Research-Based, Developmentally-Informed) enrichment intervention was designed to complement and strengthen the impact of existing Head Start programs in the dual domains of language/emergent literacy skills and social-emotional competencies. REDI was one of several projects funded by the Interagency School Readiness Consortium, a partnership of four federal agencies (the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Administration for Children and Families, the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services in the Department of Education). The projects funded through this partnership were designed to assess how integrative early interventions for at-risk children could promote learning and development across multiple domains of functioning. In addition, the projects were charged with examining processes of change and identifying mechanisms of action by which the early childhood interventions fostered later school adjustment and academic achievement.

This study examined such processes of change, with the goal of documenting hypothesized cross-domain influences on kindergarten outcomes. In particular, this study tested whether gains in the proximal language/emergent literacy and social-emotional competencies targeted during Head Start would mediate the REDI intervention effects on kindergarten academic and behavioral outcomes. In addition, it tested the hypothesis that gains in social-emotional competencies during preschool would make unique contributions to intervention effects on both academic and behavioral outcomes, even after accounting for the effects of preschool gains in language and emergent literacy skills.

The Importance of Preschool Interventions for At-Risk Children

In recent years, concerns about children's academic readiness for kindergarten have intensified, based upon longitudinal research linking kindergarten academic skill deficits with long-term underachievement and school failure (Duncan et al, 2007; Lonigan, Burgess & Anthony, 2000; Ryan, Fauth, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). Developmental research has shown that delays in oral language and emergent literacy skills, such as letter recognition and phonemic awareness, impair kindergarten readiness to read, suggesting they are important targets for preschool enrichment (Lonigan, 2006). Children growing up in poverty are at particularly high risk for delayed language and emergent literacy skill development; this risk reflects the diminished resources and reduced language stimulation that characterize the children's social environments (Lengua, Horonado, & Bush, 2007; Ryan et al., 2006).

In addition to language and emergent literacy skills, preschool social-emotional skills play an important role in school readiness. Such skills are linked directly with children's behavioral adjustment in kindergarten, and they facilitate learning. Social-emotional skills, including emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, and positive social behavior, promote peer acceptance and facilitate positive relationships with teachers (Denham, 2006; Downer, Sabol, & Hamre, 2010; Garner & Waajid, 2008). At school entry, learning engagement, reflected in behaviors such as listening, following directions, and persisting at challenging cognitive tasks, is closely related to social-emotional competence and highly related to positive peer and teacher relationships in the classroom (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999).

It appears that social-emotional development fosters both learning engagement and positive social behavior in the classroom (Ladd et al., 1999), as well as facilitating academic performance (McClelland et al., 2006; Miles & Stipek, 2006). For example, Ladd et al. (1999) found that higher levels of social participation and learning engagement at the beginning of kindergarten predicted higher achievement test scores at the end of the academic year, even controlling for initial achievement test scores.

Focusing Preschool Interventions on Academic and Social-Emotional School Readiness

Head Start was founded to enrich early learning opportunities and promote the school readiness of children growing up in poverty. A primary goal was to reduce educational disparities associated with socioeconomic status (Zhai, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2011). Although Head Start was designed to provide comprehensive support services, the predominant pressure on Head Start in recent years has been to improve children's academic skills (Konold & Pianta, 2005).

A number of rigorous evaluation studies suggest that Head Start can enhance its impact on children's language and emergent literacy skills by using evidence-based teaching strategies and curriculum materials that promote oral language, phonological awareness, and print knowledge (Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 1999; Lonigan, 2006). For example, dialogic reading programs, which encourage teachers to read interactively and engage children in active discussions, accelerate gains in children's vocabulary and oral comprehension skills (Wasik, Bond, & Hindman, 2006; Whitehurst et al., 1994). In addition, carefully sequenced learning activities during the preschool years have proven effective at boosting children's phonological awareness and letter knowledge, thereby facilitating their readiness to learn to read (Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler, 1998; Lonigan, Farver, Phillips, & Clancy-Menchetti, 2011).

Although less well-studied, recent research suggests that Head Start also can improve its impact on children's social-emotional school readiness by using evidence-based curricula (Domitrovich, Moore, Thompson, & Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, in press). For example, in a rigorous randomized-controlled trial in Head Start classrooms, Preschool PATHS (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies; Domitrovich, Greenberg, Kusche, & Cortes, 2005), which featured classroom lessons and extension activities, enhanced children's social-emotional competence (Domitrovich, Cortes, & Greenberg, 2007).

Integrated, Dual-Focus Efforts to Enrich Head Start with Evidence-Based Practices

Responding to the Interagency School Readiness Consortium's call to synthesize preschool intervention components that targeted the joint promotion of academic and social-emotional school readiness, the REDI program took advantage of the growing research base and purposefully integrated evidence-based language/emergent literacy and social-emotional interventions into one comprehensive model. In addition to the explicit curriculum and learning activities, REDI provided teachers with enhanced professional development support so they could implement the program with fidelity.

At the end of the Head Start year, children in the REDI classrooms displayed more advanced language and emergent literacy skills as well better adjustment on a broad range of social-emotional skills (see Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008, for a summary of these findings). Recent analyses revealed there were sustained effects of the REDI intervention after children transitioned to kindergarten (Bierman et al., in press).

The Present Study

The present study utilized data collected during the preschool intervention year and at the kindergarten follow-up assessment. It put the developmental model underlying REDI to a test. It sought to determine whether growth in the proximal skills targeted by the intervention during the Head Start year mediated program effects on kindergarten outcomes. It was expected that change in vocabulary, emergent literacy skills, emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, and positive social behavior during Head Start would predict reading achievement, learning engagement, and positive social behavior in kindergarten.

Given developmental theory and prior research suggesting that social-emotional school readiness may support both social and academic adjustment in kindergarten, it was further hypothesized that there would be “cross-domain” effects over time. Specifically, it was hypothesized that proximal gains in social-emotional skills during preschool might contribute to kindergarten reading skills, as well as learning engagement and positive social behavior, even after accounting for the contribution of preschool gains in vocabulary and emergent literacy skills.

Method

Forty-four Head Start classrooms in 25 centers in two primarily rural counties and one primarily urban county of Pennsylvania were stratified on location, length of program day, and student demographic characteristics. They then were randomized into REDI intervention or “usual practice” classrooms. All 4-year-old children in participating classrooms were invited to join a longitudinal development study that served as an evaluation of the REDI intervention trial. The families of 86% of eligible children consented to do so.

Participants

Over two successive cohorts, 356 4-year-old children (17% Latino, 25% African American, 54% girls) were enrolled in the REDI intervention study during their final preschool year. Reflecting their Head Start eligibility, most of the children came from families with incomes below the federal poverty limit. Children were followed after they made the transition into 202 kindergarten classrooms in 82 schools in 33 school districts.

Follow-up data were collected for 97% of the original sample at the end of Head Start and 95% of the sample at the end of kindergarten. Analyses comparing children who were and were not retained in the sample revealed few significant differences. There was not a significant difference in retention rates across the intervention and control conditions.

The Head Start REDI Intervention

Head Start REDI included evidence-based curriculum components with the goal of enhancing impact on the preschool acquisition of language/emergent literacy skills and social-emotional skills that were most central to later success (Blair, 2002). These components were designed to be integrated with the curricula already being used in the Head Start centers: High/Scope or Creative Curriculum. REDI also provided teachers with professional development support.

To strengthen children's language and emergent literacy skills, REDI facilitated daily dialogic reading (Wasik et al., 2006; Whitehurst et al., 1994) in which teachers used scripted questions and toy props to improve children's understanding of narrative, grammatical syntax, and vocabulary for words they would encounter when learning to read. To promote phonological awareness (Adams et al., 1998), REDI developed a series of sound games that exposed children to pre-reading concepts such as listening, rhyming, alliteration, phonemes, syllables, words, and sentences at a developmentally-appropriate pace. The games were organized developmentally, so that the degree of challenge and difficulty increased slowly over time. To promote print knowledge (Lonigan et al., 2000), teachers were provided with a developmentally-sequenced set of hands-on activities and materials to be used in their alphabet centers, including letter stickers, a letter bucket, materials to create a “Letter Wall,” and craft materials for various letter-learning activities. Head Start teachers were asked to complete at least four dialogic reading activities each week, three sound games each week, and three sessions at the alphabet center with each child each week; on average, they reported implementing 6.08 dialogic reading activities, 2.57 sound games, and 3.56 alphabet center activities.

To enhance children's social-emotional development, REDI implemented the Preschool PATHS curriculum (Domitrovich et al., 2005), which focuses on promoting social competence (e.g., sharing, being a good friend), emotion regulation (e.g., recognizing emotions in oneself and others), and competent social problem solving (e.g., self-control and peaceful, non-aggressive conflict management). Head Start teachers were asked to complete one PATHS lesson and one extension activity each week; on average, they reported implementing 1.77 PATHS lessons and extension activities.

In addition to the curriculum materials, REDI sought to support teaching practices associated with children's school readiness (Mashburn et al., 2008). It provided teachers with three days of inservice training in August, prior to the beginning of the intervention study, and one day of inservice training in January. REDI also provided teachers with ongoing mentoring: REDI coaches spent an average of three hours per week in the classrooms, observing teachers and demonstrating techniques, and they spent one more hour per week meeting with the lead and assistant teacher to review how the lessons from the past week had gone and to prepare for the lessons of the upcoming week. Professional development support included instruction in the use of the new curriculum materials as well as positive classroom management practices, emotion coaching, and speaking to children in ways that foster language development (e.g., questions, reflections, and expansions).

Assessments of implementation quality documented moderate to strong fidelity to the REDI program, according to teacher reports and observations by REDI coaches (Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008). Observations at the end of the year conducted by research assistants who were naïve to study condition documented that REDI teachers, compared to their counterparts in the control condition, created more nurturing and supportive emotional climates, relied on more positive behavior management practices, and used more complex language when interacting with their children (Domitrovich et al., 2009).

Data Collection Procedures

This study utilized data collected at three time points: (1) baseline assessments at the start of the preschool year, (2) post-intervention assessments at the end of the preschool year, and (3) one-year follow-up assessments in the spring of the kindergarten year. At each time point, trained research assistants conducted individual child assessments. During the preschool year, assessments were conducted at the Head Start centers in two sessions, each lasting between 30 and 45 minutes. In kindergarten, a single assessment was conducted at the child's school, lasting 45 to 60 minutes.

At the end of the preschool year, research assistants completed observations of children's peer interactions. Research assistants organized 12- to 15-minute play sessions, involving three children randomly selected from classroom rosters, in which novel and exciting toys were provided. Each child participated in a play session on two separate days. During each session, each child was observed by his/her own research assistant, who completed a series of ratings immediately afterwards. Inter-rater reliability was assessed for 23% of the play sessions (one-way random effects intraclass correlation coefficient > .70).

At the end of the preschool year and at the end of kindergarten, a trained research assistant delivered and explained the rating forms to children's teachers. After completing the ratings on their own, teachers mailed the packets to the research office. During the preschool year, lead and assistant Head Start teachers completed the rating forms independently, and their ratings were averaged.

At each time point, research assistants visited the homes of the participants and conducted individual interviews with their parents. Research assistants read all questions to parents and recorded the parents' answers to avoid any problems with low levels of literacy.

Measures of Preschool Intervention Effects

To assess the impact of intervention on the proximal skills that were targeted by REDI, we assessed change over the course of the final preschool year on constructs representing vocabulary, emergent literacy skills, emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, and positive social behavior. When possible, we tried to include measures within each construct that were based on multiple different methods of assessment or multiple different informants, so that, together, the measures comprised a broader survey of a theoretically-meaningful higher-order domain (Bollen & Lennox, 1992; Borsboom, Mellenberg, & van Heerden, 2003). All measures except teacher and observer ratings of positive social behavior were collected at the beginning and end of the preschool year.

Vocabulary

The 170-item Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (Brownell, 2000), administered with a 6-consecutive failure ceiling, was used to assess children's vocabulary. For each item, children were required to produce a word that described pictures they were shown (α = .94).

Emergent literacy skills

The 21-item Blending and 18-item Elision subscales from the Test of Preschool Early Literacy (TOPEL; Lonigan, Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 2007) were used to assess children's emergent literacy skills. The Blending subscale required children to point to the picture that best captured the combination of two words or sounds, such as “hot” and “dog” (α = .86). The Elision subscale required children to point to the picture that represented part of a deconstructed word, such as “snowshoe” without “shoe” (α = .83). Scores on the two subscales (r = .50, p < .001) were standardized and averaged together.

Emotion understanding

Two measures assessed emotion understanding. On the Assessment of Children's Emotion Skills (Schultz, Izard, & Bear, 2004), children determined whether the facial expressions in 12 photographs reflected happy, mad, sad, scared, or neutral feelings (α = .57). On the Emotion Recognition Questionnaire (Ribordy, Camras, Stafani, & Spacarelli, 1988), children listened to 16 stories describing boys or girls in emotionally evocative situations, and identified feelings by pointing to pictures of happy, mad, sad, or scared faces (α = .63). Scores on the two subscales (r = .42, p < .001) were standardized and averaged.

Competent social problem solving

An open-ended version of the Challenging Situations Task (Denham, Bouril, & Belouad, 1994) was used to assess children's competent social problem solving. Children were presented with four vignettes describing peer problems and asked how they would respond. Sample items were “What would you do if someone hit you?” and “If you wanted to play Legos and someone said ‘No,’ what would you do?” Responses were assigned to broad categories at the time of the interview (e.g., competent, aggressive, or inept), and were later re-coded by a second research assistant to establish inter-rater reliability (κ = .94). The number of competent solutions, reflecting appropriate assertion or calm negotiation, were summed across the four scenarios (α = .68).

Positive social behavior

Two measures, rated by observers (after the structured play sessions), teachers, and parents, were used to assess children's positive social behavior. The Social Competence Scale (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995) included 13 items about prosocial behavior and emotion regulation, such as sharing, helping others, and resolving peer problems independently. Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “never” to “almost always” (α = .88, .94, and .87 for observers, teachers, and parents, respectively). An adapted version of the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation-Revised (Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991) included seven items about aggressive and oppositional behavior, such as stubborn, yells, and fights.1 Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “never” to “almost always” (α = .92, .95, and .86 for observers, teachers, and parents, respectively). At the beginning of the preschool year, parent ratings of social competence and aggressive behavior, reverse scored, (r = .68, p < .001) were standardized and averaged to form a composite measure of positive social behavior. At the end of preschool, observer, teacher, and parent ratings of social competence and aggressive behavior, reverse scored, (α = .71) were standardized and averaged to form the composite measure.

Measures of Academic and Behavioral Outcomes in Kindergarten

To assess the indirect effect of the REDI intervention on distal outcomes, we assessed functioning across the domains of academic and social-emotional skills, focusing on reading achievement, learning engagement, and positive social behavior. All distal outcomes were assessed at the end of kindergarten, one year after the REDI intervention had ended.

Reading achievement

Three measures were used to assess children's reading achievement. The 36-item Print Knowledge subscale of the TOPEL (Lonigan et al., 2007) assessed children's ability to identify and name letters and words (α = .97). The 63-item Phonemic Decoding subscale of the Test of Word Reading Efficiency (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999), which evaluated phonemic knowledge and word attack skills, required children to sound out as many non-words as they could in 45 seconds. The 100-item Story Recall subscale from the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement III – R (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001), administered and scored according to standard protocols, assessed listening skills and comprehension of narrative structure by asking children to repeat back increasingly complex stories. These three tests (α = .60) were standardized and averaged to provide a general assessment of the literacy skills underlying reading achievement in kindergarten.

Learning engagement

Two measures, based on teacher reports, were used to assess children's learning engagement at school. The School Readiness Questionnaire, developed for the REDI intervention trial, included 14 items about children's intellectual curiosity and self-discipline, such as “Seems enthusiastic about learning new things” and “Can follow rules and routines.” Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (α = .96). The Inattention subscale of the ADHD Rating Scale (DuPaul, 1991) included eight items about children's difficulty concentrating on their school work, such as “Is easily distracted” and “Has trouble following directions.” Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale with response options ranging from “not at all” to “very much” (α = .93). After the Inattention subscale was reverse scored, the two measures (r = .78, p < .001) were standardized and averaged.

Positive social behavior

The same rating scales of social competence and aggressive behavior that were used to assess positive social behavior during the preschool year were used to assess positive social behavior in kindergarten. At this time point, however, only teachers and parents completed the two sets of ratings (α = .76).

Results

As reported previously (Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008), extensive comparisons of children in the Head Start REDI and Head Start control conditions revealed no statistically significant baseline differences. The randomization process appeared to create comparable groups of children prior to the intervention period.

Means and standard deviations for the variables included in this study are presented separately for children in the REDI intervention and control conditions in Table 1. To achieve one value that represented how much change had occurred during the Head Start year for each domain of child functioning, we computed residualized gain scores. Each end-of-Head Start outcome variable (e.g., vocabulary, emergent literacy skills, emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, and positive social behavior) was regressed on the baseline beginning-of-Head Start assessment of the same construct. Simple t-tests indicated statistically significant differences in group means across the REDI intervention and control conditions for change in vocabulary, emergent literacy skills, emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, and positive social behavior during Head Start. In each case, the children in the REDI intervention showed more positive adaptation than children in the “usual practice” Head Start control group. There was also a significant difference in group means for positive social behavior at the end of kindergarten.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables.

| N | Head Start-As-Usual | Head Start REDI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Change During Head Start | |||

| Vocabulary | 332 | -.12 (1.01) | .11 (.98)* |

| Emergent Literacy Skills | 335 | -.26 (.97) | .22 (.98)*** |

| Emotion Understanding | 335 | -.19 (1.02) | .16 (.96)** |

| Competent Social Problem Solving | 332 | -.19 (.86) | .17 (1.08)*** |

| Positive Social Behavior | 345 | -.17 (1.07) | .15 (.91)** |

| Kindergarten Outcomes | |||

| Reading Achievement | 334 | .01 (1.00) | -.01 (1.00) |

| Learning Engagement | 322 | -.10 (.98) | .10 (1.01) |

| Positive Social Behavior | 338 | -.14 (.97) | .12 (1.01)* |

Note: Because almost all measures were composites of multiple other measures, they all have been standardized with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Thus, a negative score does not necessarily indicate that children got worse. It could mean that they did not improve as much as other children in the sample. Asterisks represent statistically significant mean differences between children in the REDI intervention and control conditions:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Correlations among study variables, reflecting within-domain coherence in growth processes, are presented in Table 2. Growth in vocabulary was significantly associated with growth in emergent literacy skills, but not with growth in the indices of social-emotional development. Likewise, growth in emotion understanding and competent social problem solving was significantly associated with growth in positive social behavior. In a few cases, cross-domain associations were evident. For example, growth in emergent literacy skills was significantly associated with growth in emotion understanding and competent social problem solving.

Table 2. Correlations Among Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change During Head Start | |||||||

| 1 Vocabulary | |||||||

| 2 Emergent Literacy Skills | .21*** | ||||||

| 3 Emotion Understanding | .07 | .18*** | |||||

| 4 Competent Social Problem Solving | .02 | .14** | .10 | ||||

| 5 Positive Social Behavior | .07 | .08 | .15** | .14** | |||

| Kindergarten Outcomes | |||||||

| 6 Reading Achievement | .22*** | .22*** | .26*** | .19*** | .13* | ||

| 7 Learning Engagement | .14* | .19*** | .18*** | .14* | .29*** | .40*** | |

| 8 Positive Social Behavior | .09 | .08 | .13* | .08 | .36*** | .19*** | .59*** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Modeling Processes of Intervention-Facilitated Change

A central goal of this study was to examine the process of change and to determine the extent to which gains in the proximal language/emergent literacy and social-emotional skills targeted during the Head Start year accounted for improvements in children's kindergarten outcomes. To do so, we followed procedures appropriate for situations in which there are multiple possible mediators and data are nested (MacKinnon, 2008). Full information maximum likelihood was used in estimating all models to minimize any biases that might result from missing data.

Intervention effects on Head Start outcomes

The first stage of data analyses involved estimating the effect of the REDI intervention on each of the five residualized gain scores that represented the proximal targeted outcomes. These multilevel models in which children were nested within their Head Start classrooms and child sex and race served as covariates, were similar but not identical to models estimated previously (Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008). They served to demonstrate that the REDI intervention had a positive impact on child functioning across the academic and social-emotional domains.

Results from this stage of data analyses confirmed that children in the REDI intervention condition, relative to children in the “usual practice” control group, experienced greater growth in vocabulary, β = .25, p < .05; emergent literacy skills, β = .49, p < .001; emotion understanding, β = .36, p < .01; competent social problem solving, β = .36, p < .01; and positive social behavior, β = .33, p < .01. Because all residualized gain scores were standardized with a mean of 0.00 and a standard deviation of 1.00, the parameter estimates can be interpreted as approximate effect sizes. These initial analyses confirm that the REDI intervention fostered accelerated growth in a wide range of both academic and social-emotional skills during the preschool year. Tests of robustness revealed no significant differences in parameter estimates across European American, African American, or Latino American children.

Relations between change in Head Start and functioning in kindergarten

In the second stage of data analyses, we estimated the unique effects of growth in those academic and social-emotional skills during Head Start on child functioning in kindergarten. These multilevel models in which children were again nested within their Head Start classrooms, and child sex and race served as covariates, included an indicator of treatment status to control for the direct effect of the REDI intervention, in addition to the five residualized gain scores representing growth in academic and social-emotional skills during Head Start.

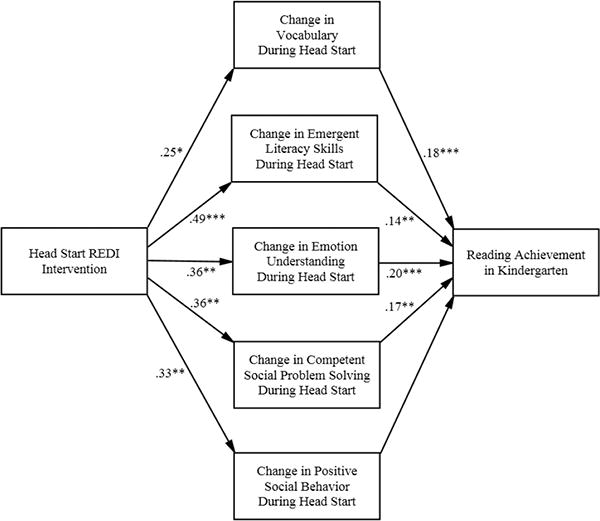

The multilevel model predicting kindergarten reading achievement is summarized and depicted in Figure 1. Four of the five residualized gain scores assessing growth during Head Start emerged as statistically significant and unique predictors of reading achievement in kindergarten: growth in vocabulary during Head Start, β = .18, p < .001; growth in emergent literacy skills, β = .14, p < .01; growth in emotion understanding, β = .20, p < .001; and growth in competent social problem solving, β = .17, p < .01. Gains in each of these proximal intervention targets during Head Start made independent predictions to kindergarten reading achievement, controlling for the effects of the other proximal intervention targets. Tests of mediation with asymmetric confidence intervals (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007) indicated that the REDI intervention had a significant indirect effect on reading achievement in kindergarten as a result of its initial effect on change in vocabulary during Head Start, μ = .05, p < .05, 95% asymmetric confidence interval for the mediated effect (CI) = .002 - .10; its effect on emergent literacy skills during Head Start, μ = .07, p < .01, CI = .02 - .13; its effect on emotion understanding during Head Start, μ = .07, p < .01, CI = .02 - .14; and its effect on competent social problem solving during Head Start, μ = .06, p < .01, CI = .02 - .12. Tests of robustness revealed no significant differences in relations for European American, African American, or Latino American children.

Figure 1. Mediated Intervention Effects on Reading Achievement.

The multilevel model predicting kindergarten learning engagement is summarized and depicted in Figure 2. In this case, three of the five residualized gain scores emerged as statistically significant and unique predictors: growth in emergent literacy skills during Head Start, β = .14, p < .01; growth in emotion understanding, β = .11, p < .05; and growth in positive social behavior, which was the most powerful predictor of learning engagement in kindergarten, β = .26, p < .001. Tests of mediation indicated that the REDI intervention had a significant indirect effect on learning engagement in kindergarten as a result of its initial effect on growth in these targeted skills during Head Start: emergent literacy skills, μ = .07, p < .01, CI = .02 - .13; emotion understanding, μ = .04, p < .05, CI = .003 - .09; and positive social behavior, μ = .09, p < .05, CI = .02 - .17. Tests of robustness revealed that growth in emergent literacy skills during Head Start uniquely predicted learning engagement in kindergarten for European American children but not African American children, whereas growth in emotion understanding uniquely predicted learning engagement for African American children but not European American children.

Figure 2. Mediated Intervention Effects on Learning Engagement.

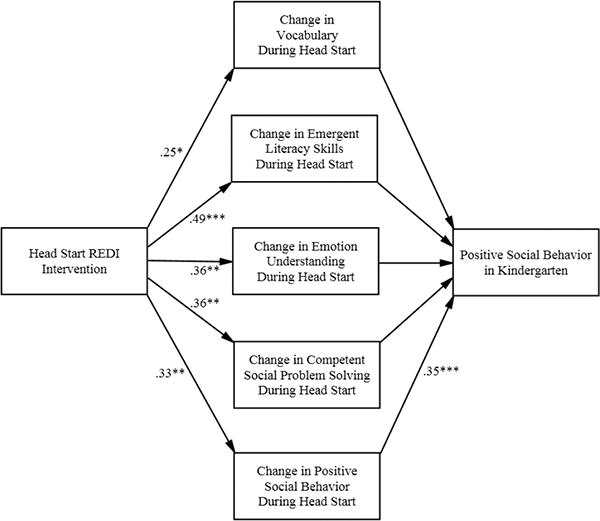

Finally, the multilevel models predicting kindergarten positive social behavior are summarized and depicted in Figure 3. In contrast to the results for reading achievement and learning engagement, in this case, only one residualized gain score emerged as a statistically significant and unique predictor of positive social behavior: change in positive social behavior during Head Start, β = .35, p < .001. The test of mediation indicated that the REDI intervention had a significant indirect effect on positive social behavior in kindergarten as a result of its initial effect on change in positive social behavior during Head Start, μ = .12, p < .05, CI = .03 - .22. Tests of robustness revealed no significant differences in relations for European American, African American, or Latino American children.

Figure 3. Mediated Intervention Effects on Positive Social Behavior.

Discussion

Funded by the Interagency School Readiness Consortium, the REDI program's central goal was to test the viability and impact of an integrated school readiness intervention targeting the dual domains of language/emergent literacy skills and social-emotional competencies. A related goal was to explore processes of change and identify mechanisms of action by which the preschool intervention fostered later academic achievement and school adjustment. Addressing these goals, this study examined links between gains in the proximal skills targeted by REDI during preschool and sustained effects on children's functioning in kindergarten.

The results document that the gains children made during preschool continued to predict their functioning one year later, after they had transitioned from Head Start to elementary school. Within-domain effects were evident: Gains in children's vocabulary and emergent literacy skills during Head Start predicted reading achievement in kindergarten, and gains in positive social behavior during Head Start predicted positive social behavior in kindergarten. In addition, cross-domain effects emerged. Specifically, Head Start gains in emotion understanding and competent social problem solving uniquely predicted reading achievement in kindergarten, adding to the concurrent gains in vocabulary and emergent literacy skills. Similarly, preschool gains in both cognitive skills (e.g., emergent literacy skills) and social-emotional skills (e.g., emotion understanding and positive social behavior) each uniquely predicted learning engagement in kindergarten.

The mediation analyses document the mechanisms of action by which the REDI preschool intervention fostered later school adjustment and attainment. They indicate that REDI contributed to kindergarten gains in reading achievement, learning engagement, and positive social behavior largely by accelerating preschool gains in the proximal skills that were targeted by the intervention (e.g., vocabulary, emergent literacy skills, emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, and positive social behavior).

These findings validate the logic model of the Head Start REDI program (Bierman, Domitrovich et al., 2008) and the approach to early childhood education promoted by the Interagency School Readiness Consortium (Griffin, 2010). They demonstrate that evidence-based social-emotional curricula, implemented with high quality and integrated with lessons promoting language/emergent literacy skills, foster later social adjustment and learning engagement in kindergarten and also accelerate the development of academic skills.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that promoting language and emergent literacy skills alone, without attending to the social-emotional competencies of children from low income families, would be less effective than the integrated approach used by REDI. Gains in language and emergent literacy skills alone did not predict improved behavioral adjustment in kindergarten; positive social behavior in kindergarten was associated specifically with gains in positive social behavior that occurred during preschool.

These findings, which validate the inclusion of high quality, evidence-based social-emotional programming in preschools serving economically-disadvantaged children, are consistent with the findings from the meta-analysis conducted by Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, and Schellinger (2011). Across 35 individual studies implemented in school settings, the provision of universal social-emotional learning programs resulted in substantial improvements in children's academic achievement, with effect sizes ranging from .15 to .39, and positive social behavior. The present study extends downward those findings, suggesting that a curriculum that integrates social-emotional learning during preschool can have similar wide-ranging effects on children's adaptation.

Cross-Domain Effects: The Value of Targeting Specific Social-Emotional Skills

The present findings also provide validation for the particular social-emotional skills targeted in the Preschool PATHS program: emotion understanding, competent social problem solving, prosocial behavior, and self-control of aggressive impulses. These proximal targets of PATHS made unique predictions to children's kindergarten adjustment.

From a theoretical perspective, there are multiple reasons to anticipate that gains in these particular social-emotional skills during preschool could affect subsequent functioning in kindergarten. For example, Preschool PATHS specifically targets emotion understanding based upon developmental research linking the capacity to recognize and label feelings with the capacity for empathy and emotional self-regulation (Bierman & Erath, 2006; Denham, 2006; Izard, 2002). To help children gain emotion understanding, the program includes lessons that present photographs and stories to illustrate and describe different feelings and associated causes. Teachers are encouraged to model and reflect emotions (e.g., emotion coaching), and children are encouraged to use small cards illustrating emotions (e.g., feeling faces) to assist them in describing their own feelings and recognizing the feelings of others.

In the REDI program, the language and understanding of emotion was also reinforced in the dialogic reading stories that were selected to parallel PATHS content. The capacity to use language to describe internal affective states allows children to redirect emotional arousal into adaptive activity, and thus inhibit reactive aggressive behavior (Izard, 2002). Naming emotions facilitates cognitive control by changing the location of neural processing from the amygdala to the prefrontal cortex (Lieberman et al., 2007). In addition, the capacity to share feelings verbally allows children to better understand the feelings of others, fostering interpersonal sensitivity and peaceful conflict management (Denham, 2006; Domitrovich et al., 2007).

To foster prosocial behavior and competent social problem solving, Preschool PATHS lessons introduce core friendship themes (e.g., lessons on caring and sharing), along with explicit training in self-control (e.g., “When upset, take a deep breath to calm down, then say the problem and how you feel”) and competent social problem solving (Domitrovich et al., 2005). Teachers were coached to help children calm down and use social problem-solving dialogue during naturally-occurring peer interactions in the classroom (Domitrovich, Gest, Gill, Jones, & DeRouise, 2009). Prosocial skills (e.g., helping, sharing, taking turns), inhibitory control of aggressive impulses, and competent social problem solving support children as they initiate and sustain positive peer interactions during the preschool years (Bierman & Erath, 2006; Coolahan, Fantuzzo, Mendez & McDermott, 2000).

Positive peer engagement, in turn, fosters enhanced learning engagement and constructive classroom participation (Coolahan et al., 2000; Ladd et al., 1999). Conversely, aggressive behavior problems in kindergarten disrupt and impair learning (Campbell, 2006; Vaughn, Hogan, Lancelotta, Shapiro, & Walker, 1992). When children experience rejection by their peers or conflict with their teachers as a result of aggressive or oppositional behavior, they are less likely to work independently and comply with classroom rules and responsibilities, creating low levels of participation that attenuate academic achievement.

The development of the executive regulatory system during the preschool years may also account for some of the cross-domain effects linking the social-emotional skills targeted by PATHS with improved cognitive readiness for school (Blair, 2002). During the preschool years, executive function skills, including working memory, inhibitory control, and attention set-shifting, show accelerated development, and function to modulate emotional arousal and regulate attention and impulse control (Blair, 2002; Riggs, Greenberg, Kusche, & Pentz, 2006). Functionally, these skills enhance children's capacity for goal-oriented learning and flexible problem solving, and support the acquisition of emergent literacy and math skills (Welsh, Nix, Blair, Bierman & Nelson, 2010). Developmental research suggests reciprocal relations among emotion understanding, emotion control, cognitive understanding, and cognitive control during the preschool years (Leerkes, Paradise, O'Brien, Calkins, & Lange, 2008). In one of the other studies funded by the Interagency School Readiness Consortium, an intervention focused on providing Head Start teachers with positive behavioral support affected children's self-regulation skills, which partially mediated gains in academic skills (Raver et al., 2011). This lends further credence to the possibility that the development of executive function skills accounts for some of the cross-domain effects linking social-emotional skill acquisition to gains in academic achievement.

The Developmental Context of Poverty and Integrated Preschool Interventions

Children growing up in poverty are particularly vulnerable to delays in the skills needed for school readiness: Over 40% of children in Head Start demonstrate delayed language skills and social skills, and over 20% exhibit high rates of disruptive behavior problems that undermine school adjustment (Macmillan, McMorris, & Kruttschnitt, 2004; Kaiser, Hancock, Cai, Foster, & Hestor, 2000; Ritsher, Warner, Johnson, & Dohrenwend, 2001). Up to 30% of children in Head Start have clinically significant behavior problems (Qi & Kaiser, 2003), and more than 10% display aggressive and antisocial behavior at least once a day (Kupersmidt, Bryant, & Willoughby, 2000).

Compared to children from higher-income families, children growing up in poverty often experience lower-quality learning opportunities within the home and in early child-care and preschool settings. They also tend to have more negative interpersonal relationships (Hart & Risley, 1995; Lengua et al., 2007). Exposure to early adversity has a negative impact on the development of the executive regulatory system. Children who experience extreme adversity in their early years, such as maltreatment or severe neglect, show increased levels of attention problems, emotion dysregulation, and language delays (Cicchetti, 2002). For these reasons, programs like Head Start REDI that integrate evidence-based curriculum components and teaching practices to promote social-emotional, as well as language/emergent literacy skill development, are particularly important.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Several features of the Head Start REDI study design enhanced our capacity to explore the preventive intervention mechanisms of action. First, the study included a large sample of children who were diverse in terms of ethnicity and the rural and urban contexts in which they lived. Second, most of the children lived in poverty and therefore were more likely to display low levels of academic and social-emotional school readiness, enhancing the potential effects of a preventive intervention. Third, this study utilized a randomized-controlled design and evaluated the impact of an intervention that was delivered in real-world settings. Because the control group included children in similar Head Start classrooms using standard High/Scope or Creative Curriculum, there is increased confidence that study findings can be attributed to the specific REDI program, rather than to more general features associated with the Head Start preschool experience. Fourth, multiple measures were used to assess gains in child skills and kindergarten outcome (e.g., direct assessments as well as teacher, parent, and observer ratings). Importantly, most of these measures were unbiased: Although Head Start teachers knew the intervention status of particular children, neither research assistants nor kindergarten teachers had access to this information. Fifth, because we examined how simultaneous changes in multiple domains of child functioning during the Head Star year affected kindergarten outcomes, the relations we identified statistically controlled for most related constructs and thus were unique.

Despite those strengths, this study also had limitations. First, as evident from Table 1, there was not a statistically significant difference in means for children in the REDI intervention and control conditions on the measures of reading achievement and learning engagement in kindergarten. More nuanced assessments of the kindergarten outcomes of children who received REDI show sustained intervention effects on some specific literacy skills (e.g., phonemic decoding) and some specific learning behaviors in kindergarten (Bierman et al., in press), but those effects were not broad enough to emerge as significant differences in the composite measures examined in the present study. Although such differences are not necessary to test for mediated or intervening variable effects (MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002), the lack of differences complicates interpretation and may indicate the presence of moderation. Although we know most results did not vary by child race, prior analyses suggest that sustained REDI intervention effects on kindergarten learning engagement may be specific to children who matriculated at lower-quality elementary schools (Bierman et al., in press). Second, the experimental design of our intervention trial does not allow claims of causation regarding how changes in functioning during Head Start might be related to kindergarten outcomes; other changes during Head Start that were not assessed in this study could be responsible for the kindergarten outcomes (Lynch, Cary, Gallop, & Ten Have, 2008). Third, the effect sizes in this study were often small.2 Finally, the relations among measures within some higher-order constructs were lower than ideal.

Summary and Implications

This study found that gains in social-emotional skills during preschool uniquely predicted reading achievement and learning engagement at the end of kindergarten, even after accounting for concurrent preschool gains in academic skills. The blending of intervention strategies to promote language/emergent literacy skills and social-emotional competencies had additive and synergistic effects on kindergarten adjustment.

In general, integrating proven practices that target multiple risk and protective factors into coherent models may increase the impact of universal prevention strategies (Domitrovich et al., 2010). A well-specified, evidence-based preschool curriculum that fosters language/emergent literacy and social-emotional skills in an intentional and integrated manner can have beneficial effects for economically-disadvantaged children across domains of functioning.

Acknowledgments

Authors' Note: This project was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants HD046064 and HD43763. The authors thank the REDI research and clinical staff members, our Head Start partners, and all of the parents, teachers, and children who made this study possible. Celene Domitrovich is an author of the Preschool PATHS curriculum, has a royalty agreement with Channing Bete, Inc., and receives income from PATHS Training, LLC. All potential conflicts of interest have been reviewed and managed by the Individual Conflict of Interest Committee at Penn State.

Footnotes

The version of this measure for teachers also included six items about relational aggression (Crick, Casas, & Mosher, 1997).

It is important to note, however, that these effect sizes represented the difference between children in Head Start REDI and Head Start-as-usual and, therefore, have no bearing on the magnitude of change that occurs from providing high-quality preschool programs to children living in poverty.

References

- Adams MJ, Foorman BR, Lundberg I, Beeler T. Phonological sensitivity in young children: A classroom curriculum. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Nix RL, Gest SD, Welsh JA, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Nelson K, Gill S. Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI program. Child Development. 2008;79:1802–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Erath SA. Promoting social competence in early childhood: Classroom curricula and social skills coaching programs. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. Blackwell Handbook on Early Childhood Development. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Domitrovich CE. Executive functions and school readiness intervention: Impact, moderation, and mediation in the Head Start REDI Program. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:821–843. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Nix RL, Heinrichs BS, Domitrovich CE, Gest SD, Welsh JA, Gill S. Effects of Head Start REDI on children's outcomes one year later in different kindergarten contexts. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12117. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of child functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K, Lennox R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equationperspective. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;110:305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, Mellengergh GJ, van Heerden J. The theoretical status of latentvariables. Psychological Review. 2003;110:203–219. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test Manual. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Maladjustment in preschool children: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. The Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development. London: Blackwell; 2006. pp. 358–378. [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Fey ME, Zhang X, Tomblin JB. Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading. 1999;3:331–361. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. The impact of social experience on neurobiological systems: Illustration from a constructivist view of child maltreatment. Cognitive Development. 2002;17:1407–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Coolahan K, Fantuzzo J, Mendez J, McDermott P. Preschool peer interactions and readiness to learn: Relationships between classroom peer play and learning behaviors and conduct. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:458–465. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Mosher M. Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:579–588. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. The emotional basis of learning and development in early childhood education. In: Spodek B, Saracho O, editors. Handbook of research on the education of young children. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Denham S, Bouril B, Belouad F. Preschoolers' affect and cognition about challenging peer situations. Child Study Journal. 1994;24:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Bradshaw CP, Greenberg MT, Embry D, Poduska JM, Ialongo NS. Integrated models of school-based prevention: Logic and theory. Psychology in the Schools. 2010;47:71–88. doi: 10.1002/pits.20452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Cortes R, Greenberg MT. Improving young children's social and emotional competence: A randomized trial of the preschool PATHS curriculum. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:67–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Gest SD, Gill S, Bierman KL, Welsh J, Jones D. Fostering high-quality teaching in Head Start classrooms: Experimental evaluation of an integrated curriculum. American Education Research Journal. 2009;46:567–597. doi: 10.3102/0002831208328089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Gest SD, Gill S, Jones DJ, DeRouise RS. Teacher factors related to the professional development process of the Head Start REDI intervention. Early Education and Development. 2009;20:402–430. doi: 10.1080/10409280802680854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT, Kusche C, Cortes R. The preschool PATHS curriculum. Channing Bete Publishing Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Moore JE, Thompson R . CASEL. Interventions that promote social-emotional learning in young children. In: Pianta R, editor. Handbook of Early Education. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Downer J, Sabol TJ, Hamre B. Teacher-child interactions in the classroom: Toward a theory of within- and cross-domain links to children's developmental outcomes. Early Education and Development. 2010;21:699–723. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul G. Parent and teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms: Psychometric properties in a community-based sample. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991;20:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development. 2011;82:405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Waajid B. The associations of emotion knowledge and teacher-child relationships to preschool children's school related developmental competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JA. Research on the implementation of preschool intervention programs: Learning by doing. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25:267–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore; Brookes: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. Translating emotion theory and research into preventive interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:796–824. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP, Hancock TB, Cai X, Foster EM, Hester PP. Parent-reported behavioral problems and language delays in boys and girls enrolled in Head Start classrooms. Behavioral Disorders. 2000;26:26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Konold TR, Pianta RC. Empirically-derived, person-oriented patterns of school readiness in typically-developing children: Description and prediction to first-grade achievement. Applied Developmental Science. 2005;9:174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Bryant D, Willoughby MT. Prevalence of aggressive behaviors among preschoolers in Head Start and community child care programs. Behavioral Disorders. 2000;26:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children's social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Paradise M, O'Brien M, Calkins SD, Lange G. Emotion and cognition processes in preschool children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2008;54:102–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI, Crockett MJ, Tom SM, Pfeifer JH, Way BM. Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychological Science. 2007;18:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ. Development, assessment, and promotion of preliteracy skills. Early Education and Development. 2006;17:91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Burgess SR, Anthony JL. Development of emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent-variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:596–613. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Farver JM, Phillips BM, Clancy-Menchetti J. Promoting the development of preschool children's emergent literacy skills: A randomized evaluation of a literacy-focused curriculum and two professional development models. Reading and Writing. 2011;24:305–337. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Wagner, Torgesen JK, Rashotte CA. TOPEL: Test of Preschool Early Literacy. Austin, TX: PRO-ED, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KG, Cary M, Gallop R, Ten Have TR. Causal mediation analyses for randomized trials. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2008;8:57–76. doi: 10.1007/s10742-008-0028-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R, McMorris BJ, Kruttschnitt C. Linked lives: Stability and change in maternal circumstances trajectories of antisocial behavior in children. Child Development. 2004;75:205–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Pianta RC, Hamre BK, Downer JT, Barbarin OA, Bryant D, Howes C. Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children's development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development. 2008;79:732–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Acock AC, Morrison FJ. The impact of kindergarten learning-related skills on academic trajectories at the end of elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2006;21:471–490. [Google Scholar]

- Miles SB, Stipek D. Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of low-income elementary school children. Child Development. 2006;77:103–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison FJ, Connor CM. The transition to school: Child-instruction transactions in learning to read. In: Sameroff AJ, editor. Transactions in development. Washington DC: American Psychological Association Books; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Qi CH, Kaiser AP. Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2003;23:188–216. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining CP, Zhai F, Bub K, Pressler E. CSRP's impact on low-income preschoolers' pre-academic skills: Self-regulation and teacher-student relationships as two mediating mechanisms. Child Development. 2011;82:362–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribordy S, Camras L, Stafani R, Spacarelli S. Vignettes for emotion recognition research and affective therapy with children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1988;17:322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Greenberg MT, Kusche CA, Pentz MA. The meditational role of neurocognition in the behavioral outcomes of a social-emotional prevention program in elementary school students: Effects of the PATHS Curriculum. Prevention Science. 2006;7:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher J, Warner EB, Johnson JG, Dohrenwend BP. Inter-generational longitudinal study of social class and depression: A test of social causation and social selection models. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:84–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.40.s84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH, Miller LJ. Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R) manual. Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Fauth RC, Brooks-Gunn J. Childhood poverty: Implications for school readiness and early childhood education. In: Spodek B, Saracho ON, editors. Handbook of research on the education of children. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Izard CE, Bear G. Children's emotion processing: Relations to emotionality and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:371–387. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA. Test of Word Reading Efficiency. Austin, TX; PRO-ED Publishing, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Hogan A, Lancelotta G, Shapiro S, Walker J. Subgroups of children with severe and mild behavior problems: Social competence and reading achievement. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik BA, Bond MA, Hindman A. The effects of a language and literacy intervention on Head Start children and teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JA, Nix RL, Blair C, Bierman KL, Nelson KE. The development of Cognitive skills and gains in academic school readiness for children from low income families. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0016738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam S, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Epstein JN, Angell AC, Payne AC, Crone DA, Fischel JE. Outcomes of an emergent literacy intervention in Head Start. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:542–555. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather NM. Woodcock-Johnson III: Tests of Cognitive Abilities. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai F, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Head Start and Urban Children's School Readiness: A Birth Cohort Study in 18 Cities. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:134–152. doi: 10.1037/a0020784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]