SUMMARY

Infectious mononucleosis is a clinical manifestation of primary Epstein–Barr virus infection. It is unknown whether genetic factors contribute to risk. To assess heritability, we compared disease concordance in monozygotic to dizygotic twin pairs from the population-based California Twin Program and assessed the risk to initially unaffected co-twins. One member of 611 and both members of 58 twin pairs reported a history of infectious mononucleosis. Pairwise concordance in monozygotic and dizygotic pairs was respectively 12·1% [standard error (s.e.)=1·9%] and 6·1% (s.e.=1·2%). The relative risk (hazard ratio) of monozygotic compared to dizygotic unaffected co-twins of cases was 1·9 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1·1–3·4, P=0·03], over the follow-up period. When the analysis was restricted to same-sex twin pairs, that estimate was 2·5 (95% CI 1·2–5·3, P=0·02). The results are compatible with a heritable contribution to the risk of infectious mononucleosis.

Keywords: Epstein–Barr virus, genetics, infectious mononucleosis, twins

INTRODUCTION

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous herpesvirus infection that persists indefinitely in the host. It is transmitted via close oral contact in the setting of childhood crowding, in which infection is common in young children and is typically asymptomatic [1]. Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is a clinical manifestation of primary EBV infection that occurs chiefly in adolescents and young adults who escaped infection as children [1].

Even when primary EBV infection occurs relatively late, symptomatic IM occurs in only a fraction of primary infections [2]. Prospective serological studies in college and military academy students in the USA, Scotland and Hong Kong show a consistent 12–13% seroconversion rate to EBV positivity in the first year of college, but the incidence of IM in the sero-converted varies greatly between institutions (range 28–74%), implying the existence of important risk factors other than age [3–7].

The extent to which genetic factors play a role in host response to initial infection, seroconversion, and manifestation of clinical symptoms of IM has been examined in a limited number of studies [8–11]. Some have reported that polymorphisms in genes coding for HLA [8] and cytokines [9–11] are associated with an increased risk of IM. However, none of these studies had enough power to adjust for other potential confounding factors.

Because identical (monozygotic; MZ) twins and fraternal (dizygotic; DZ) twins share 100% or, on average, 50% of the genotype, respectively, a comparison of twin concordance by zygosity can be used as a crude indicator of heritable susceptibility [12]. In addition, twins are matched on early childhood environment, important because early childhood EBV infection may mitigate risk of later IM. For this reason we sought to investigate the heritability of IM in twin pairs identified from a population-based registry of California-born twins.

METHODS

This study was conducted according to the guidelines set by the Declaration of Helsinki, and was completed without reference to any data that might personally identify the selected subjects. Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board.

Source of subjects and data instruments

The California Twin Program (CTP) is a population-based registry of twins born in California between 1908 and 1982, and described in detail elsewhere [13]. Briefly, twins were identified from California birth records and contact addresses were obtained by linkage with records of the California Department of Motor Vehicles. From 1991 to 2001, a 16-page screening questionnaire was sent to the 115 733 individual twins with verifiable addresses; 51 609 individual twins returned the completed questionnaire yielding a response rate similar to or better than those reported in similarly aged persons in other cohort studies [14, 15]. This study is based on the subset of 6926 double-respondent twin pairs born from 1957 to 1982 who received an updated questionnaire requesting more detailed information on medical conditions.

Each twin was asked whether either the respondent or their co-twin ever had one of several infectious diseases including IM, and if so, to indicate the age at onset. Information on zygosity, gender, race/ethnicity and education was also obtained. The twin pair constituted the unit of analysis, and the study was restricted to those twin pairs whose members agreed on their zygosity. Study variables included zygosity (MZ, DZ), sex of the pair (male-male, female-female, opposite-sex), race/ethnicity (White, Latino, African-American, Native American, Asian, Other), education level (less than college graduate, equal to or more than college graduate) and age at onset (continuous).

Statistical analysis

To determine the reliability of the proxy report from a twin about their co-twin, we assessed the percent agreement and the kappa statistic of the self-reported and proxy-reported occurrence of IM from the members of double-respondent pairs. The kappa statistic showed that the agreement between self and proxy reports was higher than predicted by chance (P<0·0001) but the magnitude was low (kappa=0·25–0·28). Although inclusion of proxy respondents produced similar results, we judged proxy reports to be insufficiently reliable and conservatively limited the formal analysis to self-reported IM from double-respondent pairs. Pairs from whom only one member reported IM were designated ‘discordant’, and those from which both members reported the same condition were designated ‘concordant’.

Pairwise concordance estimating the probability of disease occurring in both members of a pair given that one twin was affected with the disease was calculated as follows:

Asymptotic variance and standard errors (s.e.) were calculated using methods suggested by Witte et al. [16].

DZ twinning is associated with maternal age and parity [17, 18], and because large California families tend to be of lower socioeconomic status, it is a potential confounder. Pairwise concordance was reported separately by education level and sex. Because over 90% of the study population was white, we did not stratify by race.

The Cox proportional hazard function and survival curve modelling (χ2 test using phreg and lifetest procedures) were used to determine the rate of developing IM in the initially unaffected co-twin, conditioned on the age of diagnosis in the first diagnosed (index) case-twin, in MZ relative to DZ co-twins (hazard ratio). The interval of risk was defined as the time from the age of disease onset in the index case-twin to the onset of disease in the co-twin or the time of questionnaire completion (total 8257·3 person-years). We also evaluated whether the age of the index twin's onset of disease modified the risk to the co-twin. Age at disease onset was available for 87% of twins (n=585). Because males and females may have different social behaviour and therefore interpersonal contact and exposure, we repeated the analysis using only the same-sex twin pairs.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, USA) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and/or P values have been reported when applicable.

RESULTS

Of the 6926 double-respondent twin pairs who completed the updated version of the CTP questionnaire, at least one member of 669 pairs reported IM (Table 1). Twins were slightly more likely to be white but were otherwise demographically similar to the total twin population. Age at completion of the questionnaire ranged from 18 to 44 years and was similar in twins reporting IM and the total double respondent CTP twin population. With the exception of zygosity, IM-concordant and IM-discordant twin pairs were similar demographically.

Table 1.

Demographic information for California twin pairs born in 1957–1982

| Infectious mononucleosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All twins*n (%) | Concordant pairs† n (%) | Discordant pairs‡ n (%) | P value§ | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 5265 (76) | 56 (96) | 554 (91) | |

| Latino | 857 (12) | 1 (2) | 22 (4) | |

| Black | 186 (3) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | |

| Native American | 91 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | |

| Asian | 235 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (1) | |

| Other | 88 (1) | 0 (0) | 7 (1) | |

| Unknown¶ | 204 (3) | 1 (2) | 12 (2) | 0·82 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female-female | 3686 (53) | 36 (62) | 358 (59) | |

| Male-male | 1733 (25) | 11 (19) | 117 (19) | |

| Male-female | 1507 (22) | 11 (19) | 136 (22) | 0·84 |

| Zygosity | ||||

| Monozygotic | 2957 (43) | 35 (60) | 255 (42) | |

| Dizygotic | 3969 (57) | 23 (40) | 356 (58) | 0·006 |

| Zygosity – gender | ||||

| Monozygotic | ||||

| Female-female | 1994 (29) | 27 (46) | 190 (31) | |

| Male-male | 963 (14) | 8 (14) | 65 (11) | |

| Dizygotic | ||||

| Female-female | 1692 (24) | 9 (16) | 168 (27) | |

| Male-male | 770 (11) | 3 (5) | 52 (9) | |

| Male-female | 1507 (22) | 11 (19) | 136 (22) | 0·08 |

| Age (yr)∥ | 30·8 ± 6·9 | 32·3 ± 5·7 | 31·9 ± 6·4 | 0·65 |

| Total | 6926 | 58 | 611 | |

All twin pairs in whom both members completed the screening questionnaire.

Both members of the pair were diagnosed.

One member of the pair was diagnosed.

P values are based on χ2 test for the categorical variables and based on two-sample t test for the continuous variables.

Twin pairs in which members’ responses did not agree with each other.

Mean age at completion of the questionnaire ± standard deviation.

Pairwise concordance for IM was twice as high in MZ compared to DZ twins (Table 2, concordance ratio 2·0, 95% CI 1·2–3·3), and the difference was statistically significant (difference in concordance=6%, s.e. of difference=2%, P χ2=0·008). The higher concordance in MZ twins persisted when stratified by gender and education. Differences were stronger when compared to same-sex DZ twins (concordance ratio 2·3, 95% CI 1·2–4·4, difference in concordance=7%, s.e. of difference=3%, P χ2=0·008).

Age at data collection was normally distributed (data not shown). The overall mean age at onset for IM was 17±5 years. Generally, the age at onset for cases in discordant pairs was similar to the average of cases in concordant pairs (data not shown).

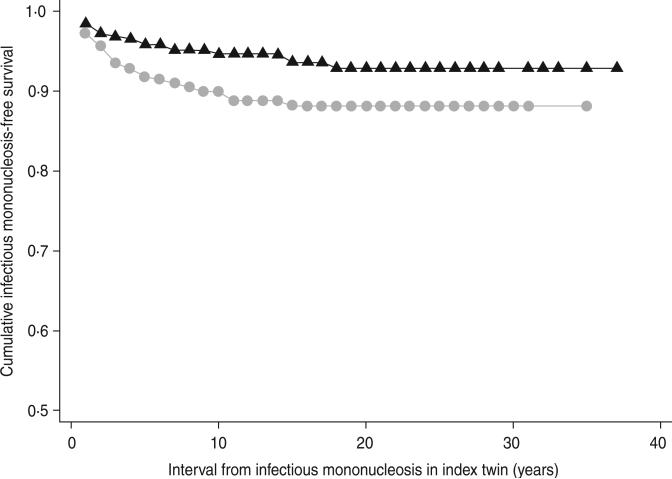

MZ co-twins of cases remained at consistently higher risk of IM over time relative to DZ twins (hazard ratio 1·9, 95% CI 1·1–3·4, P=0·03) (Fig. 1). MZ co-twins had an even higher risk compared to same-sex DZ co-twins (hazard ratio 2·5, 95% CI 1·2–5·3, P=0·02). Age at IM onset in the index case did not modify risk to the co-twin (Pinteraction=0·7, data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of freedom from infectious mononucleosis in co-twins of index cases by zygosity.  , Dizygotic,

, Dizygotic,  , monozygotic.

, monozygotic.

DISCUSSION

Concordance for IM in MZ twins was twice that of DZ twins when considered together and separately by sex and education level. Because age at exposure to EBV is a determinant of IM, it is possible that the higher MZ concordance could be due to more shared exposures in early childhood and adolescence in MZ compared to DZ twins. Exposure to infections transmitted by the oral or respiratory route requires person-to-person contact, and therefore the behavior of twins, parents and others plays a role. Critiques of twin studies have argued that MZ twins are treated more similarly by parents and peers, and thus have more similar early childhood exposures compared to DZ twins, which could contribute to higher trait concordance in MZ compared to DZ twins [19–22]. However, because IM concordance in MZ pairs was double that of DZ pairs, and because MZ twins share on average twice as many genetic characteristics as DZ twins, a genetic contribution to IM aetiology is also a plausible explanation [19, 20]. If concordance was based mainly on environmental factors (e.g. time of exposure, number of potential contacts), we might expect concordance to differ by sex, because male and female twin pairs have different levels of shared behaviour, including interpersonal contact, and therefore exposure [23]. Instead, we observed that the twofold higher concordance for MZ twin pairs was similar for both male and female pairs, consistent with an underlying sex-independent genetic susceptibility. The higher concordance in opposite-sex vs. same-sex DZ pairs is probably a reflection of chance variation.

The seroconversion rate during college age is consistent across surveyed groups, but the IM attack rate among seroconverters is variable [3–6], indicating that the rate of exposure to EBV remains consistent, but the rate of IM in the exposed shows individual variation. Crawford and colleagues have postulated that multiple exposures to sources of infection could be a risk factor for developing IM [24]. Another possible, but not mutually exclusive, explanation is that heritable factors play a role in host response and susceptibility.

Results from several studies of genetic susceptibility to primary EBV infection suggest that aheritable factor might produce differences in antigen recognition, immune response or the magnitude of cytokine production in response to infection [8–11]. The target cell of primary EBV infection is B cells and the symptoms of IM are a result of immune response to the EBV infection, including excessive production of inflamma-tory cytokines by T cells [25]. A genetic contribution to the variability in cytokine secretion in response to antigens has been demonstrated, this could also partially explain a heritable IM susceptibility [26]. Polymorphisms in genes encoding IL1-β and IL1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Rα) has been associated with EBV seropositivity and IM severity in children [9]. A haplotype in the IL10 promoter region has been linked to increased IL-10 levels in blood and protection against primary EBV infection and IM [11]. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that is also involved in cytotoxic T cell differentiation and induction [10, 11]. Variation in HLA epitopes could result in differential binding and activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against the lytic viral epitopes contributing to clinical disease [8, 27]. HLA class I polymorphisms are associated with EBV-positive Hodgkin's lymphoma [28, 29], and McAulay et al. found that these same polymorphisms are present more frequently in IM patients than in EBV-seronegative or asymptomatic EBV-seropositive individuals [8]. These findings suggest that genetic variation in antigen recognition and cytokine production may be important in IM susceptibility and support a biologically plausible mechanism for heritability.

One limitation of this study is reliance on self-reported disease status and zygosity. The validity of self-reported IM has been assessed several times with good results. Crawford and colleagues reported over 90% accuracy of self-reported IM compared to medical records of college students [24]. Self-reported zygosity is more than 95% predictive of molecular zygosity, based on studies including subjects from the present source population [13, 30]. Even if present, a minor non-differential misclassification of zygosity would slightly dampen, and not increase, the estimated concordance difference.

The unaffected co-twin of any recognized case might be scrutinized more carefully at time of presentation of the index case and thus produce a diagnostic bias, i.e. over-reporting of the IM in the second twin, which could lead to overestimation of concordance. However, such a bias is unlikely to vary much by zygosity.

We restricted our analysis to double respondent twins with disease status ascertained by self-report from each member of the pair. As expected, a higher proportion of MZ than DZ pairs responded in tandem. Although concordance is usually the most important motivating factor for twin participation, in this situation, response is not likely to be related to IM concordance because IM was one of many exposures queried and not the main focus of the questionnaire. Therefore, although a lower response rate for DZ (compared to MZ) twins in the CTP is likely, we would not expect it to affect the proportion of zygosity-specific IM concordance.

Twins in the CTP have been shown to be representative of the general California population with respect to age, sex, race and residential distribution [13]. The average age at IM diagnosis in both MZ and DZ twin cases is similar to that in IM cases in the general population [31].

Our results provide suggestive evidence for a genetic contribution to IM. Because IM has been linked to chronic conditions, such as EBV-positive Hodgkin's lymphoma [32] and multiple sclerosis [33], understanding the nature of this genetic susceptibility may provide valuable clues to the aetiology of these and other important chronic diseases.

Table 2.

Pairwise concordance for infectious mononucleosis

| All twin pairs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant* | Discordant† | % Pairwise concordance (s.e.) | |

| Infectious mononucleosis | |||

| Monozygotic twins | 35 | 255 | 12·1 (2) |

| Dizygotic twins | 23 | 356 | 6·1 (1) |

| Same-sex dizygotic twins‡ | 12 | 220 | 5·1 (2) |

| By gender | |||

| Monozygotic twins | |||

| Female-female | 27 | 190 | 12·4 (2) |

| Male-male | 8 | 65 | 11·0 (4) |

| Dizygotic twins | |||

| Female-female | 9 | 168 | 5·1 (2) |

| Male-male | 3 | 52 | 5·5 (3) |

| Male-female | 11 | 136 | 7·5 (2) |

| By education | |||

| Monozygotic twins | |||

| < 16 years of school | 20 | 134 | 13·0 (3) |

| ≥ 16 years of school | 15 | 121 | 11·0 (3) |

| Dizygotic twins | |||

| < 16 years of school | 13 | 204 | 6·0 (2) |

| ≥ 16 years of school | 10 | 152 | 6·2 (2) |

| Same-sex dizygotic twins‡ | |||

| < 16 years of school | 9 | 129 | 6·5 (2) |

| ≥ 16 years of school | 3 | 91 | 3·2 (2) |

Both members of the pair were diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis.

One member of the pair was diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis.

Subset of dizygotic twins who are male-male or female-female pairs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA110836, CA58839, P30AG0 17265) and the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (7RT-0134H, 8RT-0107H, 6RT-0354H).

The authors thank Alicia Nelson for her administrative assistance, and the twins for their continued participation in the California Twin Program.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannister BA. Upper respiratory track infections. In: Bannister BA, Begg NT, Gillespie SH, editors. Infectious Disease. Blackwell Science; Oxford: 1996. pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans AS, Niederman JC. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Evans AS, editor. Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. 3rd edn. Plenum Medical Book Company; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawyer RN, et al. Prospective studies of a group of Yale University freshmen. I. Occurrence of infectious mononucleosis. Journal of Infectious Disease. 1971;123:263–270. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.University Health Physicians and P.H.L.S. Laboratories Infectious mononucleosis and its relationship to EB virus antibody. A joint investigation by university health physicians and P.H.L.S. Laboratories. British Medical Journal. 1971;4:643–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallee TJ, et al. Infectious mononucleosis at the United States military academy. A prospective study of a single class over four years. Yale Journal Biology and Medicine. 1974;47:182–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford DH, et al. A cohort study among university students: identification of risk factors for Epstein-Barr virus seroconversion and infectious mononucleosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43:276–282. doi: 10.1086/505400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dan R, Chang RS. A prospective study of primary Epstein-Barr virus infections among university students in Hong Kong. American Journal Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1990;42:380–385. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAulay KA, et al. HLA class I polymorphisms are associated with development of infectious mononucleosis upon primary EBV infection. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:3042–3048. doi: 10.1172/JCI32377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurme M, Helminen M. Polymorphism of the IL-1 gene complex in Epstein-Barr virus seronegative and sero-positive adult blood donors. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 1998;48:219–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurme M, et al. IL-10 gene polymorphism and herpes-virus infections. Journal of Medical Virology. 2003;70(Suppl. 1):S48–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helminen ME, et al. Susceptibility to primary Epstein-Barr virus infection is associated with interleukin-10 gene promoter polymorphism. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;184:777–780. doi: 10.1086/322987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin N, Boomsma D, Machin G. A twin-pronged attack on complex traits. Nature Genetics. 1997;17:387–392. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cockburn MG, et al. Development and representativeness of a large population-based cohort of native Californian twins. Twin Research. 2001;4:242–250. doi: 10.1375/1369052012461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein L, et al. High breast cancer incidence rates among california teachers: results from the California teachers study (United States). Cancer Causes & Control. 2002;13:625–635. doi: 10.1023/a:1019552126105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolonel LN, et al. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:346–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witte JS, Carlin JB, Hopper JL. Likelihood-base-dapproach to estimating twin concordance for dichotomous traits. Genetic Epidemiology. 1999;16:290–304. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1999)16:3<290::AID-GEPI5>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnelykke B. Maternal age and parity as predictors of human twinning. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae. 1990;39:329–334. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000005237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoekstra C, et al. Dizygotic twinning. Human Reproduction Update. 2008;14:37–47. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans DM, Martin NG. The validity of twin studies. GeneScreen. 2000;1:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaves L, Foley D, Silberg J. Has the ‘equal environments’ assumption been tested in twin studies? Twin Research. 2003;6:486–489. doi: 10.1375/136905203322686473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendler KS. Overview: a current perspective on twin studies of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:1413–1425. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.11.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendler KS, et al. A test of the equal-environment assumption in twin studies of psychiatric illness. Behavior Genetics. 1993;23:21–27. doi: 10.1007/BF01067551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton AS, et al. Gender differences in determinants of smoking initiation and persistence in california twins. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2006;15:1189–1197. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawford DH, et al. Sexual history and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;186:731–736. doi: 10.1086/342596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell PJ. Role for HLA in susceptibility to infectious mononucleosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:2756–2758. doi: 10.1172/JCI33563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Craen AJ, et al. Heritability estimates of innate immunity: an extended twin study. Genes & Immununity. 2005;6:167–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hislop AD, et al. Cellular responses to viral infection in humans: lessons from Epstein-Barr virus. Annual Review of Immunology. 2007;25:587–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diepstra A, et al. Association with HLA class I in Epstein-Barr-virus-positive and with HLA class III in Epstein-Barr-virus-negative Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lancet. 2005;365:2216–2224. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hjalgrim H, et al. HLA-A alleles and infectious mononucleosis suggest a critical role for cytotoxic T-cell response in EBV-related Hodgkin lymphoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2010;107:6400–6405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915054107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson RW, et al. Determination of twin zygosity: a comparison of DNA with various questionnaire indices. Twin Research. 2001;4:12–18. doi: 10.1375/1369052012092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heath CW, Jr., et al. Infectious mononucleosis in a general population. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1972;95:46–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hjalgrim H, et al. Characteristics of Hodgkin's lymphoma after infectious mononucleosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:1324–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thacker EL, et al. Infectious mononucleosis and risk for multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Annals of Neurology. 2006;59:499–503. doi: 10.1002/ana.20820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]