Abstract

Hibernoma is a rare tumor containing prominent brown adipocytes that resemble normal brown fat. Brown fat (versus white fat) is predominantly found in hibernating mammals and infants. Brown fat adipocytes contain a higher number of small lipid droplets and a much denser concentration of mitochondria. The tumor can occur in a variety of locations however the extremities, followed by the head and neck, have been the most common sights. All variants of hibernoma described have followed a benign course with the majority presenting as a small, lobulated, nontender lesions. We present a case of a giant hibernoma arising from the pleura which invaded the intra and extra-thoracic chest.

Keywords: Hibernoma, Lipoma, Thoracic wall, Pleural neoplasm, Thoracic neoplasms

Core tip: Hibernomas are rare tumors containing brown fat. They are uncommonly located on the chest or pleura. Differentiation for other malignant tumors requires histologic evaluation. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Treatment of large and symptomatic hibernomas is surgical excision. This is curative in the majority of patients with the exception of a rare case reported having recurrence after unclear resection margins.

INTRODUCTION

Hibernomas are a type of lipid tumor containing prominent brown adipocytes similar to the brown fat of hibernating animals[1-3]. The tumor can occur in a variety of locations however the extremities, followed by the head and neck, have been the most common sights[1-4]. Hibernomas are reported to follow a benign course with the majority presenting as a small, lobulated, nontender lesions[5,6]. We present a case of a giant hibernoma arising from the pleura which invaded the intra and extra-thoracic chest.

CASE REPORT

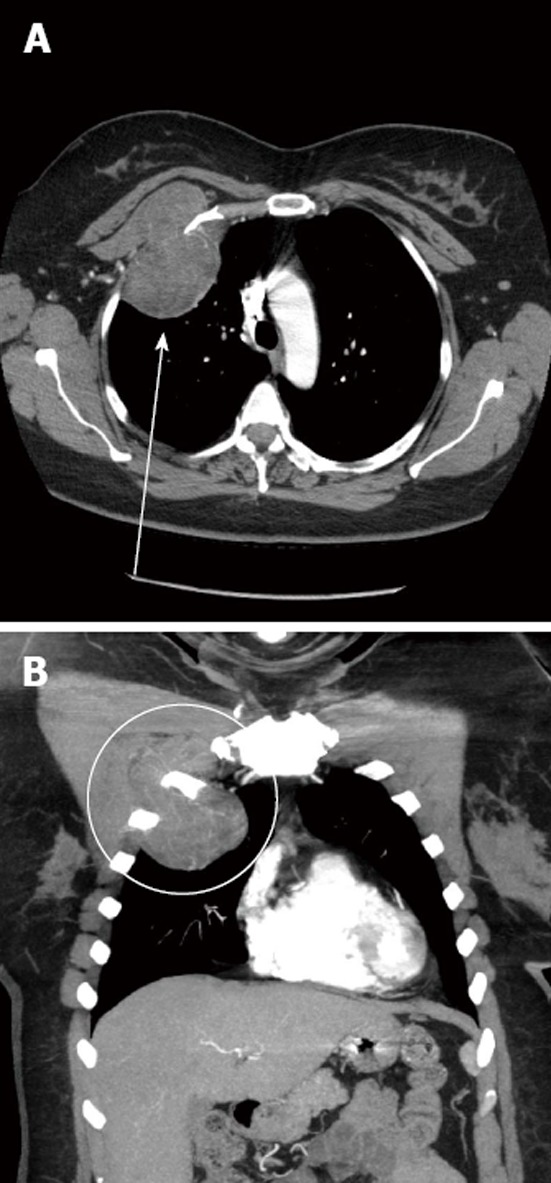

A 50-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a longstanding right anterior chest wall mass. She had vague sensation of “pressure” at the sight and believed that the mass had been there at least 5-6 years with gradual enlargement over time. A computerized tomography scan with intravenous contract was obtained of the chest (Figure 1). A circumscribed lobulated mass was seen arising from the upper anterior right pleura at the second intercostal space. The mass extended both intra thoracic and extra thoracic. The intrathoracic portion measured 9.3 cm × 5.0 cm and the extra thoracic component measured 6.6 cm × 2.9 cm. The extrathoracic component anteriorly displaced the upper portion of the pectoralis minor muscle. Subsequent needle biopsy showed features consistent with hibernoma.

Figure 1.

A computerized tomography scan with intravenous contract was obtained of the chest. A: A circumscribed lobulated mass was seen arising from the upper anterior right pleura at the second intercostal space. The mass extended both intra thoracic and extra thoracic; B: The extrathoracic component anteriorly displaced the upper portion of the pectoralis minor muscle (circle).

The patient underwent surgical excision of the mass. She was positioned with a roll under the shoulders and arms tucked at the side. The skin overlying the mass was incised and dissection taken down to the subcutaneous fat surrounding the mass. The pectus major was elevated off the chest wall on the right with careful preservation of its major blood supply. En-block resection including the pectus minor was then performed of the chest wall providing a 1 cm circumferential margin. A piece of Gore®Dualmesh® Biomaterial (WL Gore and Assoc Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, United States) was then cut to fill the defect in the chest wall which was approximately 8 cm × 11 cm. Interrupted suture was then used to attach the mesh to the edges of the chest wall defect. A chest tube was placed and the overlying pectoralis muscle flap secured to the sternum medially. A flat drain was placed between the mesh reconstruction and the muscle to prevent seroma. The wound was closed in layers and dressings placed. Compression wrapping was performed to help reduce the cavity and prevent fluid collection. The patient’s hospitalization was uncomplicated. She was discharged home on day 3 and has not evidence of recurrence.

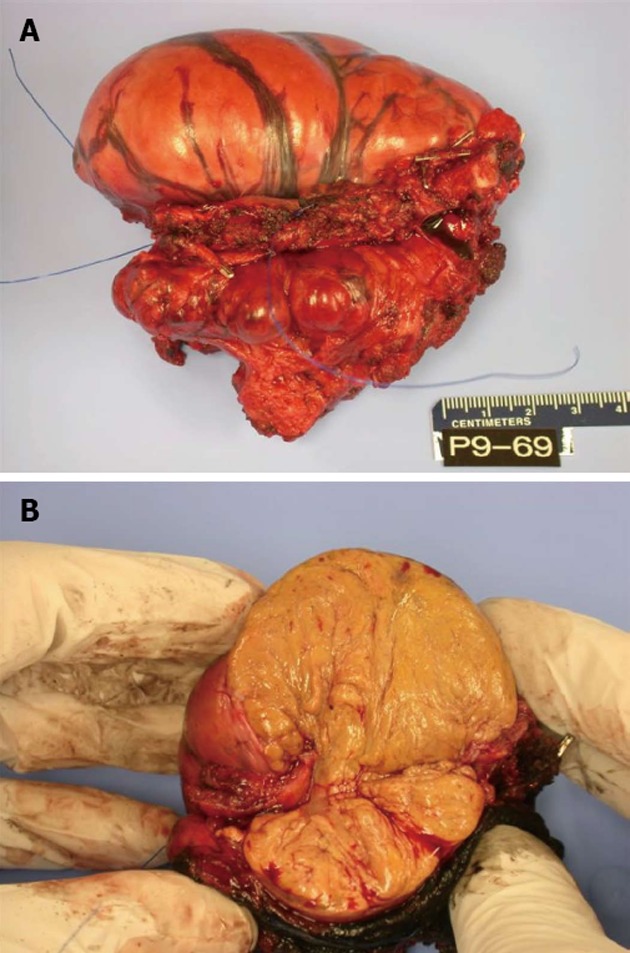

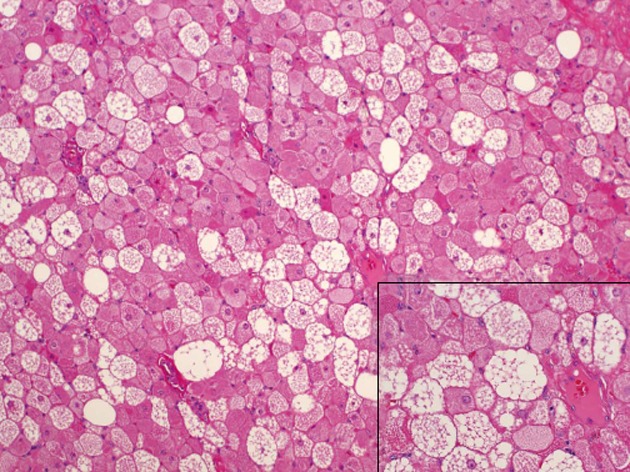

Pathology showed a specimen with dimensions 10.5 cm medial to lateral, 7.5 cm superior to inferior and 6 cm anterior to posterior (Figure 2A) containing lobular, brown fat (Figure 2B). The mass extended within the intercostal space creating bulging exophytic mass of the pleural aspect of the specimen. Immunohistochemical staining for S-100 was positive and CD34 negative. The pathologic exam of the tumor showed a well defined, solid, soft mass microscopically composed of lobules of cells with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and multivacuolated cells (Figure 3). Intermixed were also adipocyte with large single clear vacuole.

Figure 2.

Pathology showed a specimen with dimensions 10.5 cm medial to lateral, 7.5 cm superior to inferior and 6 cm anterior to posterior containing lobular, brown fat. A: The specimen with dimensions 10.5 cm medial to lateral, 7.5 cm superior to inferior and 6 cm anterior to posterior; B: Grossly the tumor contained lobular, brown fat.

Figure 3.

Microscopic evaluation of the hibernoma is characterized by vacuolated granular eosinophilic cells (hematoxylin-eosin, × 100). The inset (hematoxylin-eosin, × 400) shows a high power view of granular and multivacuolated cells in hibernoma.

DISCUSSION

Lipomas are common benign soft tissue tumors of white fat[3]. Hibernomas are a type of lipoid tumor that contain prominent brown adipocytes similar to the brown fat of hibernating animals[1,3,5-9]. The term “brown fat” was originally used by Gery[10]. They are traditionally regarded as benign tumors without the potential for malignant degeneration, however may cause symptoms as they increase in size and encroach upon other structures[6]. Clinically, hibernoma is indistinguishable from malignant tumors. As with other benign lipomatous tumors, they manifest typical cytogenetic aberrations. The most commonly reported is 11q13-21 without a common translocation partner[1,4]. Radiographically, these tumors can be difficult to distinguish from malignant tumors such as liposarcomas. Imaging can vary based upon the mixture of white versus brown fat contained in the mass[7,8]. Although magnetic resonance imaging can yield a differential diagnosis of lipomatous tumors, it cannot definitively rule out well-differentiated liposarcomas and other malignant variants[7].

The definitive diagnosis os the tumor is made by histologic confirmation. Microscopically the hibernoma is distinctive and readily differentiated from other tumors. The differential microscopic diagnosis includes adult rhabdomyoma (larger cells, glycogen rich cells with striations and crystals) and granular cell tumor (no lipid vacuoles). Hibernomas have large multi-vacuolated cells with abundant mature adipose cells, several small capillaries and no significant decomposition or adipocytic atypia[7]. Immunohistochemical staining should show S-100 positivity for lipidic cells. Oil red O-positive droplets of cytoplasmic lipid can be seen in most cases. CD34 which is seen in spindle cell and other lipoid component tumors is usually negative. Several histologic variations have been described based on the quality of hibernoma cells, nature of the stroma, and the presence of spindle cell components[3].

The majority of publications relating to hibernoma have been small series and case reports. A single clinicopathologic review from the Armed Forces Soft Tissue Registry assessed 170 cases of hibernoma confirming benign behavior and a spectrum of morphologic features[3]. The majority of tumors presented as slow growing, progressively enlarging, pain-free masses. The most common sites of occurrence were the thigh, shoulder, back and neck[3].

Treatment of large and symptomatic hibernomas is surgical excision[1,2,5,6]. This is curative in the majority of patients with the exception of a rare case reported having recurrence after unclear resection margins[4,6].

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Citak N, Deng B S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Yan JL

References

- 1.Enerbäck S. The origins of brown adipose tissue. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2021–2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr0809610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E444–E452. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigor VU, Goldstone SE, Jones J, Bernstein R, Gold MS, Weiner S. Hibernoma. A case report and discussion of a rare tumor. Cancer. 1986;57:2207–2211. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860601)57:11<2207::aid-cncr2820571122>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furlong MA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M. The morphologic spectrum of hibernoma: a clinicopathologic study of 170 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:809–814. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson SE, Schwab C, Stauffer E, Banic A, Steinbach LS. Hibernoma: imaging characteristics of a rare benign soft tissue tumor. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:590–595. doi: 10.1007/s002560100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeRosa DC, Lim RB, Lin-Hurtubise K, Johnson EA. Symptomatic hibernoma: a rare soft tissue tumor. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71:342–345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JC, Gupta A, Saifuddin A, Flanagan A, Skinner JA, Briggs TW, Cannon SR. Hibernoma: MRI features in eight consecutive cases. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dursun M, Agayev A, Bakir B, Ozger H, Eralp L, Sirvanci M, Guven K, Tunaci M. CT and MR characteristics of hibernoma: six cases. Clin Imaging. 2008;32:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gery L. In discussion of MF Bonnel’s paper. Bull Mem Soc Anat. 1914;89:111–112. [Google Scholar]