SUMMARY

The global diversity of HIV-1 represents a critical challenge facing HIV-1 vaccine development. HIV-1 mosaic antigens are bioinformatically optimized immunogens designed for improved coverage of HIV-1 diversity. However, the protective efficacy of global HIV-1 vaccine antigens has not previously been evaluated. Here we demonstrate the capacity of bivalent HIV-1 mosaic antigens to protect rhesus monkeys against acquisition of heterologous challenges with the difficult-to-neutralize simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV-SF162P3. Adenovirus/poxvirus and adenovirus/adenovirus vector-based vaccines expressing HIV-1 mosaic Env, Gag, and Pol afforded a significant reduction in the per-exposure acquisition risk following repetitive, intrarectal SHIV-SF162P3 challenges. Protection against acquisition of infection was correlated with vaccine-elicited binding, neutralizing, and functional non-neutralizing antibodies. These data demonstrate the protective efficacy of HIV-1 mosaic antigens and suggest a potential strategy towards the development of a global HIV-1 vaccine. Moreover, our findings suggest that the coordinated activity of multiple antibody functions may contribute to protection against difficult-to-neutralize viruses.

INTRODUCTION

The extraordinary degree of HIV-1 sequence diversity worldwide represents one of the most daunting challenges for the development of a global HIV-1 vaccine (Barouch, 2008; Gaschen et al., 2002; Walker and Korber, 2001). The development of a vaccine that is immunologically relevant for multiple regions of the world is therefore a key research priority (Stephenson and Barouch, 2013). One possible solution would be to develop a different HIV-1 vaccine for each geographic region and that is tailored to local circulating isolates. However, a single global vaccine would offer important biomedical and practical advantages over multiple regional clade-specific vaccines.

Mosaic antigens (Fischer et al., 2007) and conserved antigens (Letourneau et al., 2007; Stephenson et al., 2012b) represent two potential strategies to address the challenges of global HIV-1 diversity. Mosaic antigens aim to elicit increased breadth of humoral and cellular immune responses for improved immunologic coverage of diverse sequences, whereas conserved antigens aim to focus cellular immune responses on regions of greatest sequence conservation. Immunogenicity studies in nonhuman primates have shown that mosaic antigens elicit increased cellular immune breadth and depth (Barouch et al., 2010; Santra et al., 2010) as well as augmented antibody responses (Barouch et al., 2010; Stephenson et al., 2012b) as compared with natural sequence and consensus antigens. However, no previous studies have assessed the protective efficacy of any global HIV-1 antigen concepts, and it has been unclear if the immune responses elicited by in silico derived synthetic antigens will exert biologically relevant antiviral activity. This question is of particular importance given the current plans for clinical development of these universal antigens.

It has also proven challenging to evaluate the preclinical efficacy of HIV-1 immunogens that do not have SIV homologs. This is relevant for HIV-1 mosaic antigens, since HIV-1 sequence diversity in humans is biologically substantially different from SIV sequence diversity in sooty mangabees. Moreover, SIV in natural hosts exhibits markedly decreased positive selection as compared with HIV-1 in humans, presumably as a result of the lower level of immune selection pressure and a much longer evolutionary history (Fischer et al., 2012). In addition, only limited numbers of SIV sequences are available to inform mosaic vaccine design (Fischer et al., 2012). It is currently not possible to develop SIV homologs of mosaic antigens that accurately recapitulate the biology of HIV-1 mosaic antigens, and we therefore opted not to assess the protective efficacy of SIV homologs of mosaic antigens in SIV challenge models. Instead, we evaluated the capacity of HIV-1 mosaic antigens to protect against stringent simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) challenges in rhesus monkeys.

In this study, we assessed the immunogenicity of bivalent HIV-1 mosaic Env/Gag/Pol immunogens (Barouch et al., 2010) delivered by optimized Ad/MVA or Ad/Ad prime-boost vector regimens (Barouch et al., 2012), and we evaluated the protective efficacy of these vaccines against repetitive, intrarectal challenges with the stringent, difficult-to-neutralize, heterologous virus SHIV-SF162P3 in rhesus monkeys. Since SHIVs incorporate HIV-1 Env and SIV Gag/Pol (Reimann et al., 1996a; Reimann et al., 1996b), this study primarily evaluated the ability of the HIV-1 Env components of these vaccines to block acquisition of infection. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first evaluation of the protective efficacy of a candidate global HIV-1 antigen strategy in nonhuman primates. We demonstrate that binding, neutralizing, and non-neutralizing antibody responses all correlate with protection, suggesting that the coordinated activity of multiple antibody functions may contribute to protective efficacy.

RESULTS

Evaluation of a Global HIV-1 Mosaic Vaccine in Rhesus Monkeys

We immunized 36 Indian-origin rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that did not express the class I alleles associated with spontaneous virologic control (Mamu-A*01, Mamu-B*08, and Mamu-B*17) (Loffredo et al., 2007; Mothe et al., 2003; Yant et al., 2006) with Ad prime, MVA boost (Group 1; N=12) or Ad prime, Ad boost (Group 2; N=12) vector regimens expressing bivalent M mosaic Env/Gag/Pol immunogens or with sham vaccines (Group 3; N=12). In Group 1, half the animals received the Ad26 prime, MVA boost regimen, and half received the Ad35 prime, MVA boost regimen. In Group 2, half the animals received the Ad26 prime, Ad35 boost regimen, and half received the Ad35 prime, Ad26 boost regimen. One animal in Group 1 died for reasons unrelated to the study prior to the boost immunization and thus was excluded from the analysis. Groups were balanced for animals with susceptible and resistant TRIM5α alleles (Letvin et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2010). The Ad vectors expressing HIV-1 mosaic Env/Gag/Pol have been described previously (Barouch et al., 2010). The MVA vectors were constructed by inserting the HIV-1 mosaic Env and Gag/Pol expression cassettes into two distinct regions of the MVA backbone (Earl et al., 2004) (L.A.E., P.L.E., B.M., manuscript in preparation). At week 0, monkeys were primed by the i.m. route with a total dose of 4×1010 vp Ad26 or Ad35 vectors. At week 12, animals were boosted i.m. with 4×1010 vp Ad26 or Ad35 vectors or 108 pfu MVA vectors.

Binding, Neutralizing, and Non-Neutralizing Antibody Responses

Binding antibody responses were detected in all vaccinated animals by ELISA (Nkolola et al., 2010) at week 4 after the priming immunization and increased substantially following the boost immunization (Figure 1A). Binding antibodies with mean log titers of 3.3–4.9 were detected at week 16 against diverse Envs from multiple clades (Barouch et al., 2010) (92UG037, UG92/29, CN54, ZA/97/003, 92UG021, 93BR029) as well as against one of the homologous mosaic Envs (Mos1) included in the vaccine. Antibody titers declined 1–2 logs from peak to mean log titers of 2.0–3.0 by week 32, and titers were then stable through week 52 (data not shown). Antibody responses against the Env V2 loop (Haynes et al., 2012) were also detected against multiple clades (92TH023, B_MN, ConC, Mos1, Mos2) using surface plasmon resonance assays with cyclic peptides (Figure 1B) and gp70-V1V2 fusion proteins (data not shown). No significant immunologic differences were observed among the different vector regimens.

Figure 1. Vaccine-Elicited Humoral Immune Responses.

(A) Env-specific ELISAs using a diversity of Envs from multiple clades, including 92UG037 (UG37; clade A), UG92/29 (UG92; clade A), CN54 (clade C), ZA/97/003 (ZA97; clade C), 92UG021 (UG21; clade D), 93BR029 (BR29; clade F), and mosaic (Mos1; clade M) at weeks 0, 4, 16, and 32. Mean log endpoint ELISA titers +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(B) V2-specific binding assays by surface plasmon resonance using cyclic V2 peptides from multiple clades, including 92TH023 (TH23; clade AE), MN (clade B), ConC (clade C), Mos1 (clade M), and Mos2 (clade M) at weeks 0, 4, 16, and 24. V2-specific binding assays were not run with the TH23 and MN cyclic V2 peptides at week 24. Mean response units +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(C) HIV-1 tier 1 TZM-bl neutralization assays against DJ263 (clade A), SF162 (clade B), and MW965 (clade C) at weeks 0, 4, 16, and 32. Mean ID50 titers +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(D) HIV-1 tier 2 A3R5 neutralization assays against SC22 (clade B), 1086 (clade C), and DU422 (clade C) at weeks 0 and 16. Mean ID50 titers +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(E) HIV-1 tier 2 TZM-bl neutralization assays against the SHIV-SF162P3 challenge stock at weeks 0, 16, and 32. Mean ID50 titers are shown.

(F) Antibody-dependent complement deposition (ADCD) assays with YU2 (clade B) and SF162 (clade B) Env gp120. Mean % C3b deposition responses +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(G) Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) assays with SF162 (clade B) Env gp120. Mean phagocytic score responses +/− s.e.m. are shown.

Neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) against easy-to-neutralize tier 1 viruses were detected by TZM-bl virus neutralization assays (Montefiori, 2004). Mean titers of 69–153 were detected at week 16 against SF162 (clade B) and MW965 (clade C), and low mean titers of 21–31 were observed against DJ263 (clade A) (Figure 1C). Low but clear mean titers of 37–99 were also detected against 3 of 4 difficult-to-neutralize tier 2 viruses by A3R5 assays, including SC22 (clade B), 1086 (clade C), and DU422 (clade C) (Figure 1D). Moreover, low NAb titers were observed against the difficult-to-neutralize tier 2 SHIV-SF162P3 challenge virus by TZM-bl assays (Figure 1E).

Non-neutralizing functional antibody-dependent complement deposition (ADCD) (Figure 1F) and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) (Figure 1G) (Ackerman et al., 2011) responses were also observed at week 16. ADCD assays evaluated antibody-mediated C3b deposition on Env-pulsed CEM target cells, and ADCP assays assessed antibody-mediated phagocytosis of Env-pulsed fluorescent beads by THP-1 cells. Low levels of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) were also detected (data not shown) (Gomez-Roman et al., 2006). These data demonstrate that the Ad/MVA and Ad/Ad regimens expressing the mosaic Env immunogens elicited a diversity of binding, neutralizing, and non-neutralizing antibody responses.

Breadth and Depth of Cellular Immune Responses

Robust cellular immune responses against HIV-1 Env, Gag, and Pol were detected by IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (Liu et al., 2009). The magnitude and breadth of cellular immune responses (Figures 2A and 2B) were comparable for the various vector regimens tested and were similar to our previously reported findings (Barouch et al., 2010; Stephenson et al., 2012b). Detailed epitope mapping was performed using both homologous mosaic and heterologous global potential T cell epitope (PTE) peptides, and the minimal number of epitope-specific responses was determined for each animal (Supplementary Table S1). There were significantly more CD8+ than CD4+ T lymphocyte responses per animal (P=0.0006, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) (Figures 2C and 2D). Most epitope-specific responses were detected using both peptide sets, but certain epitopes were detected uniquely with either the mosaic peptides or the PTE peptides (Figure 2D). Individual epitope-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte responses showed substantial animal-to-animal variability (Supplementary Figure S1) but nevertheless appeared to cluster in immunologic hotspots (Supplementary Data S1), despite the outbred nature of the monkeys.

Figure 2. Vaccine-Elicited Cellular Immune Responses.

(A) IFN-γ ELISPOT assays using global PTE peptide pools at weeks 0, 4, and 16. Mean spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 PBMC +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(B) Numbers of reactive subpools of 10–16 peptides using PTE and mosaic peptide sets. Mean subpools +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(C) Numbers of mapped individual CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte epitopes. Mean epitopes +/− s.e.m. are shown.

(D) Individual CD8+ and CD4+ epitope-specific immune responses mapped with heterologous PTE and vaccine-matched mosaic peptide sets. 83 responses were detected by both PTE and mosaic peptides, 58 by only mosaic peptides, and 27 by only PTE peptides. Box-and-whisker plots are shown.

See also Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Table S1, and Supplementary Data S2.

Protective Efficacy, Immunologic Correlates of Protection, and Clinical Disease

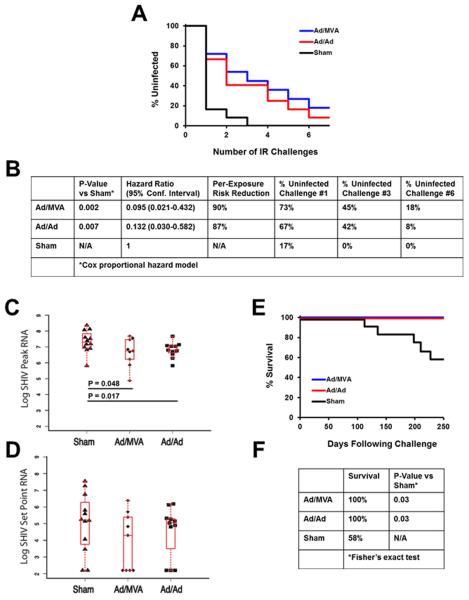

To assess the protective efficacy of the vaccines, we challenged all animals beginning at week 52 (9 months following the boost immunization) 6 times with a 1:100 dilution of our SHIV-SF162P3 challenge stock (GenBank #KF042063; Supplementary Data S2). The SHIV-SF162P3 Env had 13% amino acid sequence differences compared with Mos1 Env from the vaccine and 26% amino acid sequence differences compared with Mos2 Env. After the first challenge, 8 of 11 (73%) Ad/MVA and 8 of 12 (67%) Ad/Ad vaccinated animals remained uninfected as compared with only 2 of 12 (17%) controls (Figures 3A and 3B; P=0.03, Fisher's exact test). After the third challenge, 5 of 11 (45%) Ad/MVA and 5 of 12 (42%) Ad/Ad vaccinated animals remained uninfected as compared with 0 of 12 (0%) controls (Figures 3A and 3B; P=0.03, Fisher's exact test). As expected, absolute protection declined with additional challenges, and after the sixth and final challenge, only 2 of 11 (18%) Ad/MVA and 1 of 12 (8%) Ad/Ad vaccinated animals remained uninfected. These data reflected a 90% (P=0.002, Cox proportional hazard model using the number of challenges as a discrete time scale) and 87% (P=0.007) reduction, respectively, in the per-exposure relative risk of acquisition of infection (Figures 3A and 3B) (Hudgens and Gilbert, 2009; Hudgens et al., 2009). Thus, the mosaic HIV-1 vaccines afforded partial protection against acquisition of infection following repetitive, intrarectal, heterologous SHIV-SF162P3 challenges. No differences in protective efficacy were observed between Ad26 versus Ad35 priming in each group (data not shown).

Figure 3. Protective Efficacy Against SHIV-SF162P3 Challenges.

(A) Number of challenges required for acquisition of infection in each vaccine group.

(B) Statistical analyses include hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI), the per-exposure reduction in acquisition risk, and the absolute percentage of uninfected animals in each group after 1, 3, and 6 challenges. P-values reflect Cox proportional hazard model.

(C) Log peak SIV RNA copies/ml are depicted for each group. P-values represent Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Box-and-whisker plots are shown.

(D) Log setpoint SIV RNA copies/ml are depicted for each group at day 70. Box-and-whisker plots are shown.

(E) Clinical survival curve.

(F) Statistical analyses of survival at 250 days following challenge. P-values reflect Fisher's exact tests comparing the vaccinated groups to the control group.

We next evaluated the immunologic correlates of protection against acquisition of infection in the vaccinated animals, defined as the number of challenges required for infection. We assessed 47 humoral and cellular immunologic parameters for potential correlation with protection (Supplementary Table S2). Three parameters were significantly associated with protection after Bonferroni multiple comparison adjustments. Protection was most strongly correlated with week 16 ELISA binding antibody titers against the homologous Mos1 Env immunogen (P=1.2×10−7, Spearman rank-correlation test; Figure 4A). Protection was also correlated with ELISA binding antibody titers against other Env immunogens, although these associations were less robust (Supplementary Table S2; Supplementary Figure S2). In addition, protection was significantly correlated with NAb titers against SF162 (P=7.2×10−4; Figure 4B), which is a neutralization-sensitive virus that is related to the challenge virus SHIV-SF162P3. NAb titers against other tier 1 viruses also showed trends toward correlation with protection (Supplementary Table S2; Supplementary Figure S3). In addition, protection was correlated with functional non-neutralizing ADCP phagocytic score (P=3.0×10−4; Figure 4C), and a trend was observed with ADCD C3b complement deposition (Figure 4D). We did not, however, observe significant correlations of protection with surface plasmon resonance binding to cyclic V2 peptides or gp70-V1V2 fusion proteins or any measure of CD8+ T lymphocyte responses.

Figure 4. Immunologic Correlates of Protection.

(A) Correlation of log Mos1 ELISA titers at peak immunogenicity with the number of challenges required to establish infection.

(B) Correlation of log SF162 NAb titers at peak immunogenicity with the number of challenges required to establish infection.

(C) Correlation of SF162 ADCP phagocytic score at peak immunogenicity with the number of challenges required to establish infection.

(D) Correlation of SF162 ADCD % C3b deposition at peak immunogenicity with the number of challenges required to establish infection.

For all panels, correlates analyses included only the vaccinated monkeys that became infected and did not include the sham controls. P-values reflect uncorrected Spearman rank-correlation tests.

See also Supplementary Figures S2 and S3 and Supplementary Table S2.

Peak viral loads were modestly lower in the vaccinated animals as compared with the controls. Median peak viral loads in the Ad/MVA and Ad/Ad vaccinated monkeys were 0.50 (P=0.048, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) and 0.55 (P=0.017) logs lower, respectively, than in the controls (Figure 3C). Setpoint viral loads trended 1.14 and 0.55 logs lower in the vaccine groups, respectively, than in the controls (Figure 3D). The HIV-1 mosaic Gag and Pol immunogens in the vaccine had no detectable immunologic cross-reactivity with SIVmac239 Gag and Pol in the challenge virus by pooled peptide IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (data not shown). Thus, the modest virologic control likely reflected Env-specific immune responses, although the magnitude and breadth of Env-specific T lymphocyte responses were not clearly correlated with virologic control (Supplementary Table S2). This is consistent with our previous observations that virologic control following challenge is primarily mediated by Gag-specific cellular immune responses (Stephenson et al., 2012a), and thus it is not surprising that the observed virologic control was only modest in this study. In contrast, similar Ad/MVA and Ad/Ad vector regimens expressing SIVsmE543 antigens afforded >2 log reductions of setpoint viral loads following heterologous SIVmac251 challenges (Barouch et al., 2012).

We observed substantial clinical disease progression and AIDS related mortality in the controls. At 250 days following challenge, all of the vaccinated animals survived, as compared with only 7 of 12 (58%) of controls (Figures 3E and 3F; P=0.03, Fisher's exact test). These data confirm the stringency of our SHIV-SF162P3 challenge stock and demonstrate a survival advantage of the mosaic vaccines in this model.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates for the first time the protective efficacy of a global HIV-1 vaccine candidate in nonhuman primates. In particular, bivalent mosaic HIV-1 Env/Gag/Pol delivered by Ad/MVA or Ad/Ad vector regimens afforded substantial partial protection against repetitive, intrarectal, heterologous SHIV-SF162P3 challenges in rhesus monkeys. Although most vaccinated animals became infected by the end of the challenge series, we observed 87–90% reduction in the per-exposure probability of infection. This protective effect was likely mediated by Env-specific immune responses, since the challenge virus contained SIVmac239 Gag/Pol. These findings suggest that mosaic HIV-1 immunogens should be evaluated in clinical trials.

The majority of HIV-1 vaccine candidates have to date only demonstrated protective efficacy against low stringency, easy-to-neutralize virus challenges. For example, DNA/Ad5 vaccines afforded partial protection against acquisition of the easy-to-neutralize virus SIVsmE660 but failed to protect against the difficult-to-neutralize virus SIVmac251 (Letvin et al., 2011). Moreover, HIV-1 Env vaccines have typically only been tested for protective efficacy against easy-to-neutralize viruses, such as SHIV-SF162P4 or SHIV-BaL (Barnett et al., 2010; Barnett et al., 2008), rather than against the difficult-to-neutralize virus SHIV-SF162P3. The recent failure of the DNA/Ad5 vaccine in humans suggests that preclinical evaluations of HIV-1 vaccine candidates should be tested in difficult-to-neutralize challenge models with higher stringency. The protection observed in the present study is therefore important, since SHIV-SF162P3 exhibits a tier 2 difficult-to-neutralize phenotype that is typical of a primary virus isolate (Seaman et al., 2010). Moreover, SHIV-SF162P3 resulted in moderate to high viral loads and substantial clinical disease progression and AIDS related mortality in the controls (Figure 3).

Importance of Vaccine-Elicited Antibody Responses

Consistent with previous data in the SIVmac251 challenge model (Barouch et al., 2012), we observed that Env-specific binding antibodies correlated most strongly with protection. Binding antibodies were detected as immune correlates in the RV144 clinical vaccine trial (Haynes et al., 2012; Rerks-Ngarm et al., 2009), although we did not detect V2-specific correlates for protection in the present study, perhaps reflecting different vaccine vectors, challenge viruses, or V2 scaffolds utilized in the immunologic assays. Vaccine-elicited NAbs against SF162 also correlated with protection, and low levels of NAbs were detected against the heterologous, difficult-to-neutralize SHIV-SF162P3 challenge virus. In addition, non-neutralizing ADCP responses also correlated with protection. These data demonstrate that immunologic correlates of protection were complex and involved vaccine-elicited binding, neutralizing, and non-neutralizing antibody responses. It is therefore possible, in the absence of high titers of broadly neutralizing antibodies, that the coordinated activity of multiple antibody functions may contribute to affording protection against difficult-to-neutralize viruses. We also speculate that the mosaic Env immunogens elicited broad Env-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses that may have facilitated the induction and durability of antibody responses.

Implications for HIV-1 Vaccine Development

Mosaic antigens represent a potential strategy to improve humoral and cellular immunologic coverage of global HIV-1 diversity as compared with conventional natural sequence antigens, and they are therefore promising for HIV-1 vaccine development. Mosaic antigens may also offer a practical strategy for achieving comparable immunologic coverage utilizing fewer vaccine antigens than would be required with cocktails of natural sequence antigens. Clinical evaluation of the bivalent mosaic antigens in humans is therefore planned.

The present findings demonstrate for the first time that the immune responses elicited by these synthetic antigens can afford protection in vivo. Moreover, the correlation of multiple antibody parameters with protection suggests that both neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies may contribute to protection. A limitation of the present study, however, is that we were only able to evaluate protective efficacy against a single clade B challenge virus. Ideally, global HIV-1 antigens could be assessed for protective efficacy against a panel of diverse SHIVs. However, SHIV challenge stocks from multiple clades do not yet exist, with the exception of a limited number of clade C SHIVs (Ren et al., 2013; Siddappa et al., 2011; Siddappa et al., 2010). Thus, future studies could evaluate the protective efficacy of global mosaic HIV-1 antigens against a diversity of virus isolates after additional challenge stocks are developed.

The clinical implications of our data remain unknown and will require efficacy trials in humans. However, it is worth noting that the viral challenge in the present study was approximately 100-fold more infectious than typical sexual HIV-1 exposures in humans. Moreover, future studies are planned utilizing purified recombinant Env trimers to boost the antibody responses elicited by these mosaic vector regimens. In summary, this study demonstrates the initial proof-of-concept protective efficacy of synthetic HIV-1 mosaic antigens in rhesus monkeys and provides important new insights into the correlates of protection against stringent virus challenges.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals, Immunizations, and Challenges

36 Indian-origin, outbred, young adult, male and female, specific pathogen-free (SPF) rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that did not express the class I alleles Mamu-A*01, Mamu-B*08, and Mamu-B*17 associated with spontaneous virologic control (Loffredo et al., 2007; Mothe et al., 2003; Yant et al., 2006) were utilized for this study. Groups were balanced for susceptible and resistant TRIM5α alleles (see also Supplementary Table S3) (Letvin et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2010). Immunizations were performed by the i.m. route in the quadriceps muscles with 4×1010 vp Ad35 vectors (Vogels et al., 2003), 4×1010 vp Ad26 vectors (Abbink et al., 2007), or 108 pfu MVA vectors expressing bivalent M mosaic Env/Gag/Pol antigens (Barouch et al., 2010). Monkeys were primed at week 0 and boosted at week 12. To evaluate for protective efficacy, all monkeys were challenged repetitively beginning at week 52 with six intrarectal inoculations of the heterologous virus SHIV-SF162P3 utilizing a 1:100 dilution of our challenge stock. This virus stock was produced by expansion of the NIAID SHIV-SF162P3 stock in rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) followed by titration by the intrarectal route in rhesus monkeys and full genome sequencing (see also Supplementary Data S2). Following challenge, monkeys were bled weekly for viral loads (Siemans Diagnostics), and the date of infection was defined as the last challenge timepoint prior to the first positive SIV RNA level. Animals were followed to determine setpoint viral loads. All animal studies were approved by the appropriate Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Humoral Immune Assays

ELISA

HIV-1-specific humoral immune responses were assessed by Env ELISAs (Nkolola et al., 2010) using antigens produced in stably transfected 293 cells or commercially purchased (Polymun). V2 binding assays were performed by surface plasmon resonance with a Biacore T100 or T200 using a 1:50 serum dilution and cyclic V2 peptides containing an N-terminal biotin tag and immobilized on streptavidin-coated CM5 chips (Barouch et al., 2012).

Neutralizing antibody (NAb) assays

TZM-bl luciferase-based virus neutralization assays (Montefiori, 2004) were performed with tier 1 viruses and the tier 2 SHIV-SF162P3 challenge stock. A3R5 virus neutralization assays were conducted with tier 2 viruses.

Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP)

Functional non-neutralizing antibody responses utilized IgG purified from serum using Melon Gel columns (Thermo Scientific) and quantitated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). ADCP assays were performed as previously described (Ackerman et al., 2011). SF162 gp120 biotinylated antigen was incubated with 1 μm yellow-green fluorescent neutravidin beads (Invitrogen) overnight. The beads were then washed and resuspended at a final dilution of 1:100 in PBS-BSA. Antibodies and 9×105 antigen-labeled beads were mixed in a round bottom 96-well plate, and the plate was incubated for 2 hours. THP-1 cells (2×104 cells) were then added to each well in a final volume of 200 μL, and the plate was incubated overnight. The next day, half the culture volume was removed and replaced with 100 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde before the plates were analyzed on a BD LSR II equipped with an HTS plate reader. For analysis, the samples were gated on live cells, and the proportion of THP-1 cells phagocytosing beads was determined. A phagocytic score was calculated as follows: (% bead positive × MFI bead positive).

Rapid fluorometric antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (RF-ADCC)

The rapid fluorometric ADCC (RFADCC) assay was performed as previously described (Gomez-Roman et al., 2006). Briefly, 1×106 CEM.NKr cells (AIDS Reagent Program) were pulsed with 6 μg of recombinant SF162 gp120 for 1 hour and then washed twice in cold media. Uncoated CEM.NKr cells were used as a negative control. Both the coated and uncoated target cells were stained with 1.5 μM PKH26 (Sigma) and 100 nM 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE). After staining, the cells were resuspended at a concentration of 4×105 cells/mL, and 2×104 cells were added to each well. Purified antibodies were added (50 μg/mL), and the plates were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2 to allow the binding of the antibodies to the target cell. NK cells were isolated directly from healthy donor whole blood by negative selection using RosetteSep (Stem Cell Technologies) and added to each well at an effector:target ratio 10:1. The plates were then incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, after which the cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. ADCC activity was determined using flow cytometry and was based on the loss of CFSE on PKH+ CEM.NKr cells. The data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the percentage of CFSE loss within the PKH+ CEM.NKr population was determined.

Antibody-dependent complement deposition (ADCD)

Antibody-dependent complement activation was determined by C3b deposition on gp120-pulsed target cells. Briefly, 1×106 CEM.NKr cells were pulsed with 6 μg of recombinant gp120 (YU-2 or SF162) for 1 hour at room temperature and then washed twice in cold media. Uncoated CEM.NKr cells were used as a negative control. Plasma was utilized as a source of complement for the assay. 25 ug purified antibodies were added to 105 CEM.NKr cells in the presence of plasma diluted 1:10 in veronal buffer supplemented with 0.1% gelatin for 20 minutes at 37 degrees. Cells were washed and stained with a FITC-conjugated C3b antibody for 15 minutes, washed and fixed in 4% PFA. HIVIG was used a positive control for this assay, and heat inactivated plasma as well as antibodies from naïve controls were utilized as negative controls.

Cellular Immune Assays

HIV-1-specific cellular immune responses were assessed by IFN-γ ELISPOT assays as previously described (Liu et al., 2009). ELISPOT assays utilized pools of HIV-1 PTE or mosaic peptides. Analyses of cellular immune breadth utilized subpools of 10–16 peptides covering each antigen followed by epitope mapping using individual peptides, essentially as we have previously reported (Barouch et al., 2010). Epitope-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte responses were determined by cell depletion studies.

Statistical Analyses and Immunologic Correlates

Protection against acquisition of infection was analyzed using Cox proportional hazard models based on the exact partial likelihood for discrete time. The number of challenges was used as a discrete time scale. The hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the per-exposure relative reductions of acquisition risk were calculated for the Ad/MVA and Ad/Ad groups as compared to the control group (Hudgens and Gilbert, 2009; Hudgens et al., 2009). Absolute protection against acquisition of infection after 1, 3, and 6 challenges was quantitated as the percentage of uninfected animals as compared to the control group. Mortality at 250 days following challenge in the vaccine groups were compared to the control group by Fisher's exact tests. Analyses of virologic and immunologic data were performed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. For these tests, P<0.05 was considered significant. Immunologic correlates were evaluated by Spearman rank-correlation tests, and P<0.001 was considered significant to adjust for multiple (47) comparisons.

Supplementary Material

-

-

A global HIV-1 mosaic vaccine afforded partial protection against SHIV in monkeys

-

-

Protection correlated with binding, neutralizing, and non-neutralizing antibodies

-

-

These data suggest a strategy towards the development of a global HIV-1 vaccine

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank M. Pensiero, S. Blackmore, R. Bradsky, C. Cabral, A. Cheung, J. Goudsmit, R. Hamel, B. Hibl, S. Howell, M. Iampietro, K. Kelly, D. Lynch, M. Marovich, C. Miller, J. Nkolola, A. O'Sullivan, L. Parenteau, J. Perry, W. Rinaldi, J. Sadoff, A. SanMiguel, N. Simmons, J. Smith, F. Stephens, D. van Manen, G. Westergaard, and L. Wyatt for generous advice, assistance, and reagents. The HIV-1 PTE peptides were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. We acknowledge support from the U.S. Military Research and Material Command and the U.S. Military HIV Research Program (W81XWH-07-2-0067); the National Institutes of Health (AI052074, AI060354, AI078526, AI084794, AI095985, AI096040, AI100645); the NIAID Division of Intramural Research; the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard; and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1033091, OPP1040741).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS D.H.B., M.G.P., H.S., M.L.R., J.H.K., B.T.K., and N.L.M. designed the study and interpreted data. K.E.S., E.N.B., K.S., and A.G.M. performed the cellular immunogenicity assays. K.S., M.S., A.S.D., G.A., E.A.B., and M.R. performed the humoral immunogenicity assays. P.A., L.F.M., P.L.E., B.M., L.A.E., M.W., and M.G.P. prepared the vaccine constructs. J.L., S.T., E.S., and J.H.K. prepared and sequenced the challenge virus. M.F. led the clinical care of the rhesus monkeys. W.L., E.E.G., J.J.S., and B.T.K. performed the data and statistical analyses. D.H.B. led the study and wrote the paper with all co-authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interests. M.W., M.G.P., and H.S. are employees of Crucell.

The opinions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

REFERENCES

- Abbink P, Lemckert AA, Ewald BA, Lynch DM, Denholtz M, Smits S, Holterman L, Damen I, Vogels R, Thorner AR, et al. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J Virol. 2007;81:4654–4663. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02696-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman ME, Moldt B, Wyatt RT, Dugast AS, McAndrew E, Tsoukas S, Jost S, Berger CT, Sciaranghella G, Liu Q, et al. A robust, high-throughput assay to determine the phagocytic activity of clinical antibody samples. J Immunol Methods. 2011;366:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SW, Burke B, Sun Y, Kan E, Legg H, Lian Y, Bost K, Zhou F, Goodsell A, Zur Megede J, et al. Antibody-mediated protection against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus challenge of macaques immunized with alphavirus replicon particles and boosted with trimeric envelope glycoprotein in MF59 adjuvant. J Virol. 2010;84:5975–5985. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02533-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SW, Srivastava IK, Kan E, Zhou F, Goodsell A, Cristillo AD, Ferrai MG, Weiss DE, Letvin NL, Montefiori D, et al. Protection of macaques against vaginal SHIV challenge by systemic or mucosal and systemic vaccinations with HIV-envelope. Aids. 2008;22:339–348. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3ca57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature. 2008;455:613–619. doi: 10.1038/nature07352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, Liu J, Li H, Maxfield LF, Abbink P, Lynch DM, Iampietro MJ, SanMiguel A, Seaman MS, Ferrari G, et al. Vaccine protection against acquisition of neutralization-resistant SIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2012;482:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, O'Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, Sun YH, La Porte A, Riggs AM, Lynch DM, et al. Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat Med. 2010;16:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nm.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl PL, Americo JL, Wyatt LS, Eller LA, Whitbeck JC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Hartmann CJ, Jackson DL, Kulesh DA, et al. Immunogenicity of a highly attenuated MVA smallpox vaccine and protection against monkeypox. Nature. 2004;428:182–185. doi: 10.1038/nature02331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Apetrei C, Santiago ML, Li Y, Gautam R, Pandrea I, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Letvin NL, Nabel GJ, et al. Distinct evolutionary pressures underlie diversity in simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus lineages. J Virol. 2012;86:13217–13231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01862-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, Bhattacharya T, Yusim K, Funkhouser R, Kuiken C, Haynes B, Letvin NL, Walker BD, et al. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat Med. 2007;13:100–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaschen B, Taylor J, Yusim K, Foley B, Gao F, Lang D, Novitsky V, Haynes B, Hahn BH, Bhattacharya T, et al. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science. 2002;296:2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Roman VR, Florese RH, Patterson LJ, Peng B, Venzon D, Aldrich K, Robert-Guroff M. A simplified method for the rapid fluorometric assessment of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol Methods. 2006;308:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Evans DT, Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Sutthent R, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1275–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgens MG, Gilbert PB. Assessing vaccine effects in repeated low-dose challenge experiments. Biometrics. 2009;65:1223–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgens MG, Gilbert PB, Mascola JR, Wu CD, Barouch DH, Self SG. Power to detect the effects of HIV vaccination in repeated low-dose challenge experiments. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:609–613. doi: 10.1086/600891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau S, Im EJ, Mashishi T, Brereton C, Bridgeman A, Yang H, Dorrell L, Dong T, Korber B, McMichael AJ, et al. Design and pre-clinical evaluation of a universal HIV-1 vaccine. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letvin NL, Rao SS, Montefiori DC, Seaman MS, Sun Y, Lim SY, Yeh WW, Asmal M, Gelman RS, Shen L, et al. Immune and Genetic Correlates of Vaccine Protection Against Mucosal Infection by SIV in Monkeys. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:81ra36. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SY, Rogers T, Chan T, Whitney JB, Kim J, Sodroski J, Letvin NL. TRIM5alpha Modulates Immunodeficiency Virus Control in Rhesus Monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000738. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, O'Brien KL, Lynch DM, Simmons NL, La Porte A, Riggs AM, Abbink P, Coffey RT, Grandpre LE, Seaman MS, et al. Immune control of an SIV challenge by a T-cell-based vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2009;457:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature07469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffredo JT, Maxwell J, Qi Y, Glidden CE, Borchardt GJ, Soma T, Bean AT, Beal DR, Wilson NA, Rehrauer WM, et al. Mamu-B*08-positive macaques control simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 2007;81:8827–8832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montefiori D. Current Protocols in Immunology. Vol 12.11. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mothe BR, Weinfurter J, Wang C, Rehrauer W, Wilson N, Allen TM, Allison DB, Watkins DI. Expression of the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule Mamu-A*01 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J Virol. 2003;77:2736–2740. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2736-2740.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkolola JP, Peng H, Settembre EC, Freeman M, Grandpre LE, Devoy C, Lynch DM, La Porte A, Simmons NL, Bradley R, et al. Breadth of neutralizing antibodies elicited by stable, homogeneous clade A and clade C HIV-1 gp140 envelope trimers in guinea pigs. J Virol. 2010;84:3270–3279. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02252-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann KA, Li JT, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park IW, Karlsson GB, Sodroski J, Letvin NL. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996a;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann KA, Li JT, Voss G, Lekutis C, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Lin W, Montefiori DC, Lee-Parritz DE, Lu Y, et al. An env gene derived from a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate confers high in vivo replicative capacity to a chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996b;70:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3198-3206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W, Mumbauer A, Gettie A, Seaman MS, Russell-Lodrigue K, Blanchard J, Westmoreland S, Cheng-Mayer C. Generation of lineage-related, mucosally transmissible subtype C R5 simian-human immunodeficiency viruses capable of AIDS development, induction of neurological disease, and coreceptor switching in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2013;87:6137–6149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00178-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, Premsri N, Namwat C, de Souza M, Adams E, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2209–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra S, Liao HX, Zhang R, Muldoon M, Watson S, Fischer W, Theiler J, Szinger J, Balachandran H, Buzby A. Mosaic vaccines elicit CD8+ T lymphocyte responses that confer enhanced immune coverage of diverse HIV strains in monkeys. Nat Med. 2010;16:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nm.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MS, Janes H, Hawkins N, Grandpre LE, Devoy C, Giri A, Coffey RT, Harris L, Wood B, Daniels MG, et al. Tiered categorization of a diverse panel of HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses for assessment of neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2010;84:1439–1452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02108-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddappa NB, Hemashettar G, Wong YL, Lakhashe S, Rasmussen RA, Watkins JD, Novembre FJ, Villinger F, Else JG, Montefiori DC, et al. Development of a tier 1 R5 clade C simian-human immunodeficiency virus as a tool to test neutralizing antibody-based immunoprophylaxis. J Med Primatol. 2011;40:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddappa NB, Watkins JD, Wassermann KJ, Song R, Wang W, Kramer VG, Lakhashe S, Santosuosso M, Poznansky MC, Novembre FJ, et al. R5 clade C SHIV strains with tier 1 or 2 neutralization sensitivity: tools to dissect env evolution and to develop AIDS vaccines in primate models. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson KE, Barouch DH. A global approach to HIV-1 vaccine development. Immunol Rev. 2013;254:295–304. doi: 10.1111/imr.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson KE, Li H, Walker BD, Michael NL, Barouch DH. Gag-specific cellular immunity determines in vitro viral inhibition and in vivo virologic control following simian immunodeficiency virus challenges of vaccinated rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2012a;86:9583–9589. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00996-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson KE, SanMiguel A, Simmons NL, Smith K, Lewis MG, Szinger JJ, Korber B, Barouch DH. Full-length HIV-1 immunogens induce greater magnitude and comparable breadth of T lymphocyte responses to conserved HIV-1 regions compared with conserved-region-only HIV-1 immunogens in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2012b;86:11434–11440. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01779-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels R, Zuijdgeest D, van Rijnsoever R, Hartkoorn E, Damen I, de Bethune MP, Kostense S, Penders G, Helmus N, Koudstaal W, et al. Replication-deficient human adenovirus type 35 vectors for gene transfer and vaccination: efficient human cell infection and bypass of preexisting adenovirus immunity. J Virol. 2003;77:8263–8271. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8263-8271.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BD, Korber BT. Immune control of HIV: the obstacles of HLA and viral diversity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:473–475. doi: 10.1038/88656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yant LJ, Friedrich TC, Johnson RC, May GE, Maness NJ, Enz AM, Lifson JD, O'Connor DH, Carrington M, Watkins DI. The high-frequency major histocompatibility complex class I allele Mamu-B*17 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J Virol. 2006;80:5074–5077. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5074-5077.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.