Abstract

Aim

Previous positron emission tomography (PET) [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) studies in Parkinson’s disease (PD) demonstrated that moderate to late stage patients display widespread cortical hypometabolism, whereas early stage PD patients exhibit little or no cortical changes. However, recent studies suggested that conventional data normalization procedures may not always be valid, and demonstrated that alternative normalization strategies better allow detection of low magnitude changes. We hypothesized that these alternative normalization procedures would disclose more widespread metabolic alterations in de novo PD.

Methods

[18F]FDG PET scans of 26 untreated de novo PD patients (Hoehn & Yahr stage I-II) and 21 age-matched controls were compared using voxel-based analysis. Normalization was performed using gray matter (GM), white matter (WM) reference regions and Yakushev normalization.

Results

Compared to GM normalization, WM and Yakushev normalization procedures disclosed much larger cortical regions of relative hypometabolism in the PD group with extensive involvement of frontal and parieto-temporal-occipital cortices, and several subcortical structures. Furthermore, in the WM and Yakushev normalized analyses, stage II patients displayed more prominent cortical hypometabolism than did stage I patients.

Conclusion

The use of alternative normalization procedures, other than GM, suggests that much more extensive cortical hypometabolism is present in untreated de novo PD patients than hitherto reported. The finding may have implications for our understanding of the basic pathophysiology of early-stage PD.

Keywords: Positron-emission tomography, Fluorodeoxyglucose F18, Parkinson disease

During the past decades, brain imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) and [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) has been increasingly used to evaluate cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRglc) in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD). Previous [18F]FDG PET studies in PD reported a metabolic pattern characterized by reduced CMRglc in several frontal and parietal areas and relative hypermetabolism in widespread subcortical regions, including the lentiform nucleus, thalamus, brainstem, white matter, and primary sensory-motor areas.1, 2 However, it was recently suggested that relative subcortical hypermetabolism in PD patients may be an artifact due to biased normalization procedures employed in analyses.3

The normalization of regional tracer uptake to a reference region is a mathematical transformation commonly employed in analyses of PET data. Normalization is mandatory without fully quantitative data. But even when quantitative data are available normalization reduces the considerable intra- and interindividual CMRglc variability associated with physiological and non-physiological noise, which limits the detection of statistically significant differences between patients and controls.4, 5 The most widely used normalization procedure of CMRglc computes the ratio of a voxel value to the global mean (GM) of all grey matter voxels (i.e., GM normalization). However, GM normalization has the fundamental prerequisite that no systematic between-groups differences in the CMRglc mean global values are present. In analyses of patients with neurodegenerative brain disorders such as PD, this requirement could easily be violated. The presence of global CMRglc reductions in PD, as reported in many studies,6-9 compromises the GM normalization procedure. Importantly, biased normalization occurs even if between-groups differences in mean global values do not reach statistical significance3. Therefore, since global CMRglc is probably decreased in PD patients, GM normalization is not applicable, as it would generate the impression of metabolic increases in regions, in which CMRglc is merely preserved.

Alternative useful reference regions for normalization include the white matter (WM), the pons, and the cerebellum. The WM has been demonstrated to be a reliable reference region,10 since no [18F]FDG studies in PD patients reported metabolic alterations in this area.6-8 In addition, Yakushev and colleagues recently proposed a method for data-driven a posteriori determination of the normalization reference region.11 The method was subsequently validated on simulated data. This type of data was specifically chosen since it represents a plausible pattern of perturbed metabolism in early PD – i.e. a pattern spatially similar to late-stage disease, but of lower magnitude. In this setting, Yakushev normalization recovered 5-20 times more of the true signal present in the data than was achieved by using GM normalization of the same data.12

It is a well-established fact that PD is characterized by progressive cortical hypometabolism as the disease advances from early to later stages.13 Studies of moderate to late-stage patients consistently reported widespread cortical hypoperfusion and metabolism.9 In contrast, previous studies of early-stage PD showed little or no decreases of cortical metabolism.1, 13-15 However, when alternative normalization procedures were applied to analyze early-stage PD, patients showed widespread cortical hypoperfusion in the same regions as seen at late-stage disease.9 These contrasting results obtained with different normalization procedures suggest that the validation of a normalization reference region should always be carefully considered, especially when analyzing early-stage PD patients. To this end, de novo untreated PD patients represent an ideal PD sample, since they not only are at early disease stages, but also offer the unique opportunity to study disease processes without modulatory effects due to pharmachological therapy.

The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate glucose metabolism changes in a group of de novo, untreated PD patients, as compared to normal age-matched controls. We assess metabolic differences between groups with voxel-based analysis using GM, WM, and Yakushev normalization procedures, in order to estimate potential consequences of different normalization methods especially at early-stage PD.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We included 26 consecutive de novo untreated PD patients (17 males, mean age: 65.3±6.4 years). The PD sample overlaps with previous work.16 The inclusion criteria were: 1) clinical diagnosis of possible PD according to Gelb criteria;17 2) decrease of striatal dopamine transporter density as measured with single photon emission computed tomography, 3) confirmed clinical diagnosis of PD at a 2-year follow-up after PET scanning. The exclusion criteria were: 1) present or past therapy with antiparkinsonian drugs; 2) presence of cognitive impairment (Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) <26); 3) presence of medical conditions or history of significant conditions that may affect brain structure or function; 4) white matter vascular disease and atrophy on brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Before initiation of specific therapy for PD, all patients underwent neurological examination and [18F]FDG PET within a period of one week at our University Institution. Clinical severity of disease was assessed with Hoehn &Yahr (H&Y) scores 18 and the motor part (part III) of the Unified PD Rating Scale (UPDRS III).19 The 26 de novo PD subjects were stratified according to the H&Y score in two subgroups: 17 H&Y score I (PDI) and 9 H&Y score II (PDII). Demographic data, UPDRS III scores, and H&Y scores are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical data of PD patients and normal controls.

| Demographic/clinical data | PD | NL |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects (number) | 26 | 21 |

| Age (years) | 65.3±6.4 | 62.4±9.0 |

| Gender (male/female) | 17/9 | 14/7 |

| MMSE score | 28.7±1.2 | 29.2±0.8 |

| H&Y score [range] | 1.6±0.4 [1-2] | - |

| UPDRS III score | 14.5±4.8 | - |

Values are mean±standard deviation. PD: Parkinson’s disease patients; NL: normal controls; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; H&Y: Hoehn and Yahr scale; UPDRS: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

Twenty-one healthy, unmedicated age-matched control subjects (14 males, mean age: 62.4±9.0 years) were enrolled at the Center for Brain Health of New York University. All normal control (NL) subjects received clinical, neurological, neuropsychological, MRI and [18F]FDG PET examinations, to exclude the presence of medical conditions or history of significant conditions affecting brain structure or function.

All subjects provided written informed consent and the study was approved by Ethical Committees of both Institutions.

MRI acquisition

MRI brain scan was performed on 1.5 T MRI scanner (Florence: Philips Gyroscan NT Intera; NYU: General Electric Signa imager) with T1-, and T2-weighted sequences (matrix 512×512, voxel size 0.49×0.49×6.60 mm). Images were reconstructed into 20 slices with 6mm slice thickness in axial, coronal and sagittal orientation.

[18F]FDG PET data acquisition

All subjects were injected with a dose of 370 MBq [18F]FDG, in resting state, in a dimly lighted room with minimal background noise. Thirty minutes after injection, a scan lasting 20 minutes was acquired on a GE PET scanner (Florence: GE Advance, New York University: LS Discovery; G.E. Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). All PET images were corrected for photon attenuation, scatter, and radioactive decay, and reconstructed by iterative algorithm into a 256×256 matrix with a pixel dimension of 2.15 mm and slice thickness of 4.25 mm.

Statistical parametric mapping

PET images were converted from DICOM into Analyze format using the MIPAV software and then processed using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London) running on Matlab 7.8 (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA). A 12- parameter linear affine transformation and a non-linear three-dimensional deformation were applied to each subject scan to realign and spatially normalize images to a reference stereotactic template (Montreal Neurological Institute -MNI-, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec). The normalized images were then smoothed with a Gaussian filter to a resultant resolution of 12 mm FWHM.

Image data were proportionally scaled using three different types of normalization: 1) GM normalization. The threshold was left at the SPM default 0.8. 2) WM normalization was carried out by using the WM mean as normalization value. The entire WM was segmented on individual MRI images using the SPM dedicated tool; a probabilistic map was subsequently generated and the final WM mask was produced including only voxels at a probability of 0.8 or higher. The WM mask included only core WM, so as to minimize spillover from the cortical grey matter. For the same reason, WM normalization was done prior to any additional Gaussian filtering of the PET data. 3) PET images were also analyzed with the Yakushev normalization method,11 which defines the normalization reference region a posteriori. The method’s first step is a standard GM normalized analysis. Then, the final normalization mask is defined on the basis of the output t-map from the first analysis. The t-map is thresholded so as to include only voxels showing relative CMRglc increase in the PD group with t-values>2 (P<0.05); it was demonstrated on simulated data that a t>2 mask minimizes the risk of false positive results.12 Importantly, since true hypermetabolism has been demonstrated in certain small basal ganglia and thalamic subnuclei in animal PD models,20-23 we excluded the entire basal ganglia/thalamus region from the normalization mask. Finally, the original data were normalized using the new mask and a subsequent voxel-based analysis was performed to produce the final results. The final Yakushev mask included several WM regions and the cerebellum.

Volumes of interest analysis

In the volumes of interest (VOI) analysis, four grey matter VOIs for frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes were created using WFU Pickatlas tool for SPM8.24 Mean voxel-wise values within the VOIs were extracted from SPM designs for all normalization procedures and expressed as normalized CMRglc (CMRglcnorm).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS 18 (SPSS inc., Chicago, IL). Differences in demographical and clinical measures between PD patients and NL were examined with independent sample Student t tests and χ2 tests, as appropriate. Differences in VOI measures between NL, PDI and PDII were examined with the General Linear Model (GLM) with post-hoc LSD tests. The GLM was used to examine the effects of other variables, such as age, gender and MMSE as covariates. Results were examined at P<0.05.

For SPM8 analysis, a two sample t-test was used to explore CMRglc differences between PD groups and NL. Age and MMSE were set as nuisance variables. The significance threshold was set to P<0.05, corrected for Family Wise Error (FWE) 25 and cluster extent was set >30 voxels. Coordinates of local maxima were converted from MNI to Talairach space using the “mni2tal” function (http://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/Imaging/Common/mnispace.shtml) and labeled according to the Talairach and Tournoux space26 by using the Talairach Daemon Client Version 2.0 (http://ric.uthscsa.edu/projects/talairachdaemon.html).27, 28

Results

Subjects

PD and NL groups were comparable for age, gender distribution and MMSE score (Table I). After stratification according to the H&Y score, the 26 de novo PD patients were divided into two subgroups: 17 H&Y score I (PDI) and 9 H&Y score II (PDII). There were no significant differences between the two subgroups concerning age, gender distribution, and MMSE score.

SPM analysis

Clusters of reduced metabolism detected in the comparison between the PD group and NL by the different types of normalization are illustrated in Figure 1 and listed in Table II.

Figure 1.

SPM clusters showing significant relative CMRglc reduction in the comparison between de novo PD patients and NL by different types of normalization (P<0.05, FWE corrected). Note that a separate t-value scale was used in the bottom row, due to the very extreme t-values found in the Yakushev analysis. Abbreviations. GM: global grey matter mean; WM: white matter.

Table II.

Brain regions showing significant differences between PD patients and NL by different types of normalization.

| Cluster extent | Coordinates* | Z † | Anatomical area | Brodmann area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM normalization: Relative hypometabolism in PD patients as compared to NL | ||||

| 1749 | −50 −70 5 | 6.09 | Left middle occipital gyrus | 37 |

| −55 −60 −4 | 5.93 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 37 | |

| −48 −55 18 | 4.66 | Left superior temporal gyrus | 22 | |

| 106 | −38 25 −11 | 5.36 | Left inferior frontal gyrus | 47 |

| 200 | −63 −35 39 | 5.32 | Left inferior parietal lobule | 40 |

| −57 −49 36 | 4.69 | Left supramarginal gyrus | 40 | |

| 67 | 50 5 26 | 4.56 | Right inferior frontal gyrus | 6 |

| 54 | −46 3 24 | 4.92 | Left inferior frontal gyrus | 6 |

| GM normalization: Relative hypermetabolism in PD patients as compared to NL | ||||

| 118 | −20 27 −3 | 5.87 | Left frontal lobe white matter | |

| −24 31 4 | 4.49 | Left frontal lobe white matter | ||

| 57 | 26 −15 41 | 4.86 | Right frontal lobe white matter | |

| 26 −27 40 | 4.16 | Right frontal lobe white matter | ||

| 617 | −6 −40 −18 | 4.82 | Left cerebellum (culmen) | |

| 14 −51 −16 | 4.49 | Right cerebellum (culmen) | ||

| 180 | 28 −15 12 | 4.72 | Right lentiform nucleus (putamen) | |

| 34 −23 −2 | 4.70 | Right caudate nucleus | ||

| WM normalization: Relative hypometabolism in PD patients as compared to NL | ||||

| 13350 | −40 25 −10 | 6.62 | Left inferior frontal gyrus | 47 |

| −46 −70 7 | 6.24 | Left middle occipital gyrus | 19 | |

| −46 35 −5 | 6.15 | Left middle frontal gyrus | 47 | |

| −63 −39 39 | 6.10 | Left inferior parietal lobule | 40 | |

| −48 −73 22 | 5.98 | Left middle temporal gyrus | 39 | |

| −57 −57 −4 | 5.90 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 37 | |

| −53 −7 −21 | 5.90 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 20 | |

| −55 −60 −4 | 5.90 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 37 | |

| −50 −40 28 | 5.81 | Left inferior parietal lobule | 40 | |

| 553 | 20 12 3 | 6.46 | Right lentiform nucleus (putamen) | |

| 385 | −16 12 3 | 6.24 | Left lentiform nucleus (putamen) | |

| 4232 | 51 35 −7 | 6.02 | Right inferior frontal gyrus | 47 |

| 51 3 24 | 5.88 | Right inferior frontal gyrus | 6 | |

| 51 27 28 | 5.76 | Right middle frontal gyrus | 9 | |

| 18 65 12 | 5.71 | Right superior frontal gyrus | 10 | |

| 992 | 48 −64 3 | 5.72 | Right middle temporal gyrus | 37 |

| 46 −78 −5 | 4.87 | Right inferior occipital gyrus | 19 | |

| 896 | 14 −72 44 | 5.34 | Right precuneus | 7 |

| 14 −90 27 | 5.00 | Right cuneus | 19 | |

| 332 | −10 61 14 | 5.18 | Left superior frontal gyrus | 10 |

| −8 52 36 | 4.52 | Left superior frontal gyrus | 9 | |

| −8 47 42 | 4.39 | Left superior frontal gyrus | 8 | |

| 165 | −8 −19 −1 | 5.02 | Left thalamus | |

| −18 −29 1 | 4.96 | Left thalamus | ||

| 201 | 14 −23 1 | 5.01 | Right thalamus | |

| 318 | 53 4 −29 | 4.94 | Right middle temporal gyrus | 21 |

| 57 −11 −20 | 4.79 | Right inferior temporal gyrus | 20 | |

| Yakushev normalization: Relative hypometabolism in PD patients as compared to NL | ||||

| 42086 | −50 1 22 | 7.64 | Left inferior frontal gyrus | 44 |

| −40 25 −11 | 7.25 | Left inferior frontal gyrus | 47 | |

| −46 −68 3 | 7.16 | Left middle occipital gyrus | 37 | |

| −57 −58 −2 | 6.99 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 37 | |

| −55 −62 −2 | 6.98 | Left middle temporal gyrus | 37 | |

| −42 −19 −26 | 6.72 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 20 | |

| −53 −7 −22 | 6.58 | Left inferior temporal gyrus | 20 | |

| −46 37 −7 | 6.28 | Left middle frontal gyrus | 47 | |

| −63 −35 37 | 6.28 | Left inferior parietal lobule | 40 | |

| −48 −43 28 | 6.27 | Left inferior parietal lobule | 40 | |

| −59 −47 37 | 6.21 | Left supramarginal gyrus | 40 | |

| 12772 | 55 15 24 | 7.17 | Right inferior frontal gyrus | 44 |

| 14 −72 46 | 6.48 | Right precuneus | 7 | |

| 50 −68 3 | 6.41 | Right middle occipital gyrus | 37 | |

| 51 28 24 | 6.23 | Right middle frontal gyrus | 46 | |

| 50 37 −7 | 6.09 | Right middle frontal gyrus | 47 | |

| 18 65 10 | 5.92 | Right superior frontal gyrus | 10 | |

| 38 32 28 | 5.87 | Right middle frontal gyrus | 9 | |

| 55 −11 −20 | 5.65 | Right inferior temporal gyrus | 20 | |

| 53 4 −29 | 5.32 | Right middle temporal gyrus | 21 | |

| 51 −27 3 | 5.18 | Right superior temporal gyrus | 22 | |

| 63 −31 38 | 4.83 | Right inferior parietal lobule | 40 | |

| 900 | −8 61 17 | 5.69 | Left superior frontal gyrus | 10 |

| −10 45 42 | 5.38 | Left superior frontal gyrus | 8 | |

| −6 40 16 | 5.06 | Left anterior cingulate | 32 | |

| 258 | −18 −29 | 0 6.37 | Left thalamus | |

| 253 | 16 −25 1 | 5.95 | Right thalamus | |

| 232 | −14 10 3 | 5.97 | Left caudate nucleus | |

| −20 8 1 | 5.91 | Left lentiform nucleus (putamen) | ||

| 245 | 25 10 3 | 6.20 | Right lentiform nucleus (putamen) | |

| 10 15 4 | 5.84 | Right caudate nucleus | ||

| 202 | 14 34 20 | 5.47 | Right anterior cingulate | 32 |

Coordinates (x, y, z) from Talairach and Tournoux

Z values at the peak of maximum significance at P<0.05, FWE corrected.

GM: global grey matter mean; NL: normal controls; PD: Parkinson’s disease patients; WM: white matter.

Using GM normalization, clusters of significant relative hypometabolism were detected in frontal lobe bilaterally (Inferior Frontal Gyrus) and in parietal (Inferior Parietal Lobule, Supramarginal Gyrus), temporal (Inferior and Superior Temporal Gyri) and occipital (Middle Occipital Gyrus) lobes of the left hemisphere of PD patients compared to NL (P’s<0.05, FWE corrected). Significant relative hypermetabolism in the PD group vs NL was observed in sub-gyral WM of bilateral frontal lobes, cerebellum and lentiform/capsula interna/thalamus intersections (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

SPM clusters of significant relative hypermetabolism in de novo PD patients compared to NL after GM normalization (P<0.05, FWE corrected).

Using WM normalization, larger clusters of relative metabolic decreases, reflecting more widespread hypometabolism, were detected in the PD group compared to NL, involving frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobes, putamen and thalamus of both hemispheres (P’s<0.05, FWE corrected). No relative hypermetabolism was detected in cortical or subcortical regions.

Using Yakushev normalization, yet larger clusters of relative hypometabolism were detected in the PD group compared to NL, involving frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobes, putamen, thalamus and cerebellar cortex of both hemispheres (P<0.05, FWE corrected). No relative hypermetabolism was detected in any region.

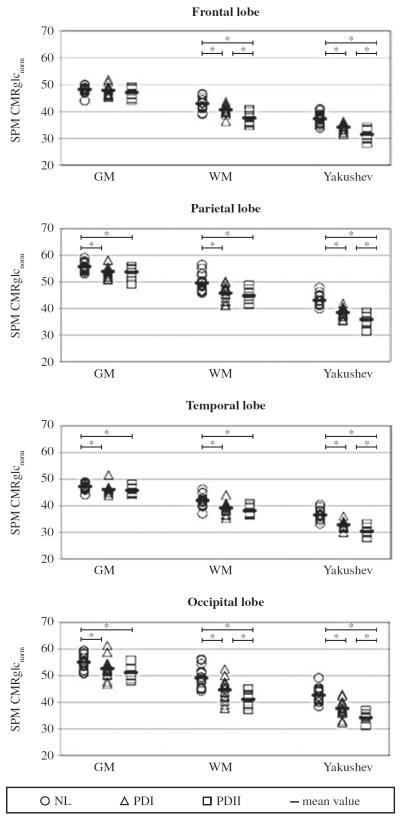

VOI analysis

Using GM normalization, the comparison of NL, PDI and PDII subgroups revealed significant group differences in parietal, temporal and occipital lobes (P<0.05). On post-hoc examination, both PDI and PDII subgroups showed reduced CMRglcnorm in parietal, temporal and occipital VOIs compared to NL (P<0.05), but there were no significant differences between PDI and PDII.

Using both WM and Yakushev normalization, the comparison between NL, PDI and PDII showed significant differences between groups in frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes (P<0.01).

Using WM normalization, there were significant differences in frontal and occipital VOIs between all the groups under examination (NL>PDI>PDII) (P<0.05), while in parietal and temporal VOIs there were no differences between PD subgroups (PDI and PDII).

Using Yakushev normalization, significant differences were detected in frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital VOIs between all the groups (NL>PDI>PDII) (P<0.05).

Figure 3 shows the normalized CMRglcnorm data for the four VOIs, using the three different types of normalization.

Figure 3.

Normalized CMRglc data for frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes, using the three different types of normalization. Abbreviations. GM: global grey matter mean normalization; NL: normal controls; PDI: Parkinson’s disease patients with H&Y score I; PDII: Parkinson’s disease patients with H&Y score II; SPM CMRglc-norm: normalized values of cerebral metabolic rate of glucose; WM: white matter normalization; Yakushev: Yakushev normalization; *: significant difference, P<0.05.

Discussion

This [18F]FDG PET study demonstrates the effect of different normalization procedures on the analysis of brain metabolic changes in untreated de novo PD patients compared to age-matched controls. In the voxel-based analysis, standard GM normalization produced small clusters of cortical hypometabolism and fairly widespread relative hypermetabolism in subcortical regions, mostly involving white matter. A comparable pattern of relative subcortical hypermetabolism was previously reported in GM normalized studies of moderate to late stage PD,9, 13, 29 as well as in a wide range of other brain conditions, such as Alzheimer’s, Lewy body dementia, schizophrenia, and hepatic encephalopathy.10 These data strongly suggest that relative hypermetabolism in regions known to be spared by pathology is a common artifact due to inappropriate GM normalization.

With respect to PD, this hypothesis is given further support by three lines of evidence. First, in a recent review of the PD animal model literature,23 there was no convincing evidence for the presence of hypermetabolism in any of these large subcortical regions, but only in small subcortical structures, such as external pallidum, peduncolopontine nucleus and ventrolateral and ventroanterior thalamic nuclei. However, these regions are below detection threshold by nearly all PET and single photon emission tomography (SPECT) devices in typical sample-sizes of 20-30 subjects. Second, in more than 25 published quantitative PET and SPECT studies, absolute cortical hypometabolism and hypoperfusion were often reported in PD patients, whereas absolute hypermetabolism was never robustly detected.3 Third, the largest quantitative perfusion study of PD was recently published30 (Melzer et al, Brain 2011 Mar;134(Pt 3):845-55). The authors analyzed perfusion MRI data with GM normalization, which disclosed the usual pattern of subcortical relative increases and quite small clusters of cortical relative decreases. However, when subsequently analyzing the quantitative values, the relatively decreased regions exhibited large absolute decreases, whereas the relatively increased subcortical regions displayed identical mean values between the PD and control group. The “in between” regions, which displayed neither increased, nor decreased relative changes, actually also exhibited significant absolute decreases. The study performed by Melzer et al. therefore provides independent confirmatory evidence for the physiological validity of the present findings, and more generally, for the use of Yakushev normalization in PD.

Our use of WM and particularly Yakushev normalization revealed a much more widespread pattern of cortical hypometabolism in de novo PD patients. This pattern is similar to that reported in moderate to late-stage PD.9, 31-34 Importantly, a nearly identical pattern of cortical hypoperfusion was also recently reported in medicated early stage (H&Y I-II) PD – but only when using Yakushev normalization.9 Together with previous reports,9 the present Yakushev normalized data set suggests that the characteristic pattern of decreased cortical perfusion and metabolism is not confined to advanced disease, but rather that this pattern is present at the early stages of PD.

In this study, we selected de novo unmedicated PD patients to demonstrate that the pattern of altered metabolism is characteristic of the disease process itself, and is not an effect of acute or chronic treatment. Interestingly, both WM and Yakushev normalizations also proved able to differentiate between PD patients at H&Y stage I and II, as demonstrated by the VOI analysis. This finding, that only the use of such alternative normalization procedures allows the correlation between cortical metabolism and disease severity, has a clinically important and meaningful implication, confirming the possible role of [18F]FDG PET as a biomarker of disease severity in PD patients. Future studies will be performed to demonstrate if the use of WM and Yakushev normalizations could detect metabolic alteration with a better cognitive correlate than GM normalization.

The presence of widespread cerebral hypometabolism in PD patients is consistent with known early degeneration of various neurotransmitter systems. It is well known that 50-70% or more of mesencephalic dopamine neurons are lost at debut of motor symptoms.35 Moreover, cortical hypometabolism may also be secondary to cortical cholinergic dysfunction resulting from the loss of afferent cholinergic cortical input.36 Two recent PET studies reported significant reductions of cortical cholinergic innervation in patterns similar to the pattern of hypometabolism detected in the PD patients in this study. This was reported in both early-stage,37 and in later-stage PD patients.31

Some limitations must be mentioned. The study contained a relatively small number of subjects. However, we considered crucial the selection of de novo unmedicated PD patients, since they represent an ideal PD sample, offering the opportunity to study disease processes without modulation effects due to pharmachological therapy. Second, we would have preferred an analysis of fully quantitative CMRglc data, since this has the potential to more conclusively clarify the extent and degree of metabolic alterations in PD. It is, however, unlikely that an analysis of quantitative data would have disclosed significant findings, due to the substantial data variation present in absolute CMRglc measures. Very substantial sample sizes are needed to detect biologically relevant differences of 10-20% in quantitative PET studies10. For this reason, continued efforts to determine optimal normalization strategies are still an important research topic.

Another critical point of this study is the use of two different PET scanners; however, acquisition and reconstruction methodologies were identical and the effect of possible differences in spatial resolution of PET scanners was minimized by spatial normalization and filtering procedures.38 Besides, it is important to note that the present pattern of cortical hypometabolism bears very close similarity to previously published patterns in GM normalized late-stage PD data and to the recently published pattern of hypoperfusion in Yakushev normalized early-stage PD data.9 It seems highly unlikely that such similarity among the patterns should arise by chance, indicating that the present pattern of hypometabolism reflects a real pathophysiological manifestation in de novo PD.

Conclusions

The present [18F]FDG PET study demonstrated that the choice of normalization procedures greatly impacts the results of voxel-based statistical analyses. Using validated, alternative normalization methods, we detected widespread cortical hypometabolism in untreated de novo PD patients. Furthermore, the method allowed differentiation between patients with H&Y stage I and II. The present findings indicate a more extensive cortical involvement in early-stage PD than previously reported, bearing implications for the general understanding of the pathophysiology of the disorder.

Acknowledgments

Funding.—NYU work was supported by NIH/NIA grants AG032554, AG13616 and NIH/NCRR grant M01-RR0096. University of Florence work was supported by Ministry of Health Funding 2007 “Development of ADNI-based imaging markers for use by the National Health System”.

Footnotes

This study has been presented at the Annual Congress of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, 2010, Wien.

Conflicts of interest.—The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Eidelberg D, Moeller JR, Dhawan V, Spetsieris P, Takikawa S, Ishikawa T, et al. The metabolic topography of parkinsonism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:783–801. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckert T, Barnes A, Dhawan V, Frucht S, Gordon MF, Feigin AS, et al. FDG PET in the differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorders. Neuroimage. 2005;26:912–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghammer P, Cumming P, Aanerud J, Gjedde A. Artefactual subcortical hyperperfusion in PET studies normalized to global mean: lessons from Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage. 2009;45:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friston KJ, Frith CD, Liddle PF, Dolan RJ, Lammertsma AA, Frackowiak RS. The relationship between global and local changes in PET scans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;19:458–66. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Brodie JD, Hitzemann RJ. Inter-subject variability of brain glucose metabolic measurements in young normal males. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1457–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berding G, Odin P, Brooks DJ, Nikkhah G, Matthies C, Peschel T, et al. Resting regional cerebral glucose metabolism in advanced Parkinson’s disease studied in the off and on conditions with [18F]FDG-PET. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1014–22. doi: 10.1002/mds.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohnen NI, Minoshima S, Giordani B, Frey KA, Kuhl DE. Motor correlates of occipital glucose hypometabolism in Parkinson’s disease without dementia. Neurology. 1999;52:541–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu MT, Taylor-Robinson SD, Chaudhuri KR, Bell JD, Labbè C, Cunningham VJ, et al. Cortical dysfunction in non-demented Parkinson’s disease patients: a combined (31)P-MRS and (18)FDGPET study. Brain. 2000;123:340–52. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borghammer P, Chakravarty M, Jonsdottir KY, Sato N, Matsuda H, Ito K, et al. Cortical hypometabolism and hypoperfusion in Parkinson’s disease is extensive: probably even at early disease stages. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:303–17. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borghammer P, Jonsdottir KY, Cumming P, Ostergaard K, Vang K, Ashkanian M, et al. Normalization in PET group comparison studies – The importance of a valid reference region. Neuroimage. 2008;40:529–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yakushev I, Hammers A, Fellgiebel A, Schnidtmann I, Scheurich A, Bchholz HG, et al. SPM-based count normalization provides excellent discrimination of mild Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment from healthy aging. Neuroimage. 2009;44:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borghammer P, Aanerud J, Gjedde A. Data-driven intensity normalization of PET group comparison studies is superior to global mean normalization. Neuroimage. 2009;46:981–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C, Tang C, Feigin A, Lesser M, Ma Y, Pourfar M, et al. Changes in network activity with the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:1834–46. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghaemi M, Raethjen J, Hilker R, Rudolf J, Sobesky J, Deuschl G, et al. Monosymptomatic resting tremor and Parkinson’s disease: a multitracer positron emission tomographic study. Mov Disord. 2002;17:782–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Y, Tang C, Moeller JR, Eidelberg D. Abnormal regional brain function in Parkinson’s disease: truth or fiction? Neuroimage. 2009;45:260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berti V, Polito C, Ramat S, Vanzi E, De Cristofaro MT, Pellicanó G, et al. Brain metabolic correlates of dopaminergic degeneration in de novo idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:537–44. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:181–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahn S, Elton RL, members of the UPDRS Development Committee . Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. In: Fahn S, Mardsen CD, Calne DB, Goldstein M, editors. Recent development in Parkinson’s disease. Macmillan Healthcare information; Florham Park, NJ: 1987. pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartzman RJ, Alexander GM. Changes in the local cerebral metabolic rate for glucose in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 1985;358:137–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezard E, Crossman AR, Gross CE, Brotchie JM. Structures outside the basal ganglia may compensate for dopamine loss in the presymptomatic stages of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2001;15:1092–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0637fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casteels C, Lauwers E, Bormans G, Baekelandt V, Van Laere K. Metabolic-dopaminergic mapping of the 6-hydroxydopamine rat model for Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:124–34. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borghammer P, Cumming P, Aanerud J, Forster S, Gjedde A. Subcortical elevation of metabolism in Parkinson’s disease – a critical reappraisal in the context of global mean normalization. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1233–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worsley KJ, Marret S, Neelin P, Vandal AC, Friston KJ, Evans AC. A unified statistical approach for determining significant signals in images of cerebral activation. Hum Brain Mapp. 1996;4:58–73. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1996)4:1<58::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.; New York, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lancaster JL, Summerln JL, Rainey L, Freitas CS, Fox PT. The Talairach Daemon, a database server for Talairach Atlas labels. Neuroimage. 1997;5:s633. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lancaster JL, Woldorff MG, Parsons LM, Liotti M, Freitas CS, Rainey L, et al. Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;10:120–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200007)10:3<120::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imon Y, Matsuda H, Ogawa M, Kogure D, Sunohara N. SPECT image analysis using statistical parametric mapping in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1583–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melzer TR, Watts R, MacAskill MR, Pearson JF, Rüeger S, Pitcher TL, et al. Arterial spin labelling reveals an abnormal cerebral perfusion pattern in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2011;134:845–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein JC, Eggers C, Kalbe E, Weisenbach S, Hohmann C, Vollmar S, et al. Neurotransmitter changes in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia in vivo. Neurology. 2010;74:885–92. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d55f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Laere K, Santens P, Bosman T, De Reuck J, Mortelmans L, Dierckx R. Statistical parametric mapping of (99m)Tc-ECD SPECT in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy with predominant parkinsonian features: correlation with clinical parameters. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:933–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mito Y, Yoshida K, Yabe I, Makino K, Hirotani M, Tashiro K, et al. Brain 3D-SSP SPECT analysis in dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moeller JR, Nakamura T, Mentis MJ, Dhawan V, Spetsieres P, Antonini A, et al. Reproducibility of regional metabolic covariance patterns: comparison of four populations. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114:2283–301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obeso JA, Marin C, Rodriguez-Oroz C, Blesa J, Benitez-Temino B, Mena-Segovia J, et al. The basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease: current concepts and unexplained observations. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:S30–S46. doi: 10.1002/ana.21481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimada H, Hirano S, Shinotoh H, Aotsuka A, Sato K, Tanaka N, et al. Mapping of brain acetylcholinesterase alterations in Lewy body disease by PET. Neurology. 2009;73:273–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herholz K, Salmon E, Perani D, Baron JC, Holthoff V, Frolich L, et al. Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. Neuroimage. 2002;17:302–16. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]