Abstract

Bone metastasis in breast cancer is a significant clinical problem. It not only indicates incurable disease with a guarded prognosis, but is also associated with skeletal-related morbidities including bone pain, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia. In recent years, the mechanism of bone metastasis has been further elucidated. Bone metastasis involves a vicious cycle of close interaction between the tumor and the bone microenvironment. In patients with bone metastases, the goal of management is to prevent further skeletal-related events, manage complications, reduce bone pain, and improve quality of life. Bisphosphonates are a proven therapy for the above indications. Recently, a drug of a different class, the RANK ligand antibody, denosumab, has been shown to reduce skeletal-related events more than the bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid. Other strategies of clinical value may include surgery, radiotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals, and, of course, effective systemic therapy. In early breast cancer, bisphosphonates may have an antitumor effect and prevent both bone and non-bone metastases. Whilst two important Phase III trials with conflicting results have led to controversy in this topic, final results from these and other key Phase III trials must still be awaited before a firm conclusion can be drawn about the use of bisphosphonates in this setting. Advances in bone markers, predictive biomarkers, multi-imaging modalities, and the introduction of novel agents have ushered in a new era of proactive management for bone metastases in breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, bone metastases, bisphosphonates, denosumab, biomarkers, optimal management

Background

Bone is the most common site of recurrence in metastatic breast cancer. Before the era of bisphosphonates, the incidence of bone as the site of metastasis in metastatic breast cancer was as high as 65%–75%,1,2 with a mean skeletal morbidity rate of 2.2–4.0 events per year.3 In patients with operable disease, the cumulative incidence of bone metastases was 8% at two years and 27% at 10 years. In early breast cancer, the presence of high-risk features, such as age <35 years, tumor size >2 cm, more than four lymph nodes involved, and estrogen receptor-negative status, further increases the risk of developing bone metastases, with nodal disease showing the highest cumulative incidence of 15% at two years and 41% at 10 years.4 Bone-only metastases have a better outcome than visceral metastases, with a median survival of 20 months after first bone relapse compared with three months after first liver recurrence.5 However, the morbidity associated with bone metastases cannot be underestimated. More than 50% of these patients develop skeletal-related events, and this necessitates radiotherapy to bone in 41% and surgical intervention in 10%.6 Given the enormous burden that skeletal-related events have on breast cancer patients and our society, there has been much research on the pathophysiology, prevention, and management of bone metastases in the last 20 years. This paper aims to summarize the key issues in this area.

Pathophysiology of breast cancer bone metastases

Normal bone physiology

Normal bone formation is a coordinated dynamic process of active bone production by osteoblasts and bone remodeling by osteoclasts. Osteoblasts arise from mesenchymal stem cells after stimulation by transcription factor core-binding factor alpha-1.7 There are a variety of local growth factors, eg, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), insulin growth factor (IGF), bone morphogenic protein, and systemic factors (platelet-derived growth factor, prostaglandins, and parathyroid hormone) that stimulate osteoblasts to differentiate into mature osteocytes, producing alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and calcified bone matrix.8 Recent research suggests that Wnt/β-catenin is a major regulator of osteoblastogenesis, such that antagonism of this signaling pathway (eg, by Dickkopf-1) has been implicated in osteopenia in animal models.9 Osteoclasts, on the other hand, arise from monocyte precursor cells with the major role of bone resorption by expressing high concentrations of cathepsin K on collagen type 1 in the bone matrix.8 While osteoclasts are also stimulated by local factors within the bone microenvironment, such as interleukin-6, interleukin-1, prostaglandins, and colony-stimulating factors from osteoblasts, the key factor for osteoclast production is the receptor activator of nuclear factor (NF)-κB ligand (RANK-L).8 Normally, osteoblasts, stromal cells, and, to a lesser extent, activated T cells release RANK-L upon stimulation by osteotrophic factors, such as parathyroid hormone, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and thyroxine.9 RANK-L binds to RANK on the surface of osteoclasts and activates the transcription factor, NF-κB, which is essential for the generation and survival of the osteoclast.7 To maintain this equilibrium, osteoprotegerin acts as the decoyreceptor for RANK-L and inhibits osteoclast function and differentiation.8,10 Recently, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand was found to be the second ligand of osteoprotegerin. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand normally initiates cell apoptosis by activating caspase receptors. Binding of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand to osteoprotegerin may paradoxically enhance cell survival.11 Whilst RANK-L/RANK is one crucial pathway that maintains the homeostasis of bone metabolism, there are other ways by which osteoblasts interact with osteoclasts to achieve this balance. One nonredundant alternate pathway involves membrane bound-colony stimulating factor-1. Membrane bound-colony stimulating factor-1 is produced by osteoblasts and also acts on the target receptor expressed by osteoclast progenitors.7 Membrane bound-colony stimulating factor-1 is a survival factor for osteoclasts, and also appears to induce their differentiation.12 Thus, osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis are normally tightly regulated by paracrine factors within the bone microenvironment, as well as by hormonal factors, and it is likely that the levels of these factors, such as the RANKL/osteoprotegerin/TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand ratio, are crucial to normal bone metabolism.

Organized and multistep process of tumor migration

Bone metastasis is not a random event, but an organized and multistep process that involves tumor intravasation, survival of cells in the blood circulatory system, extravasation into the surrounding tissue, initiation and maintaining growth, and vascularization/angiogenesis.13 To execute this complex operation, there has to be an interplay of multiple gene mutations, protein expression, and signaling of aberrant pathways. In a landmark study, a multigenic examination of breast cancer bone metastases identified key gene expression signature involved in this process early. These genes include C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), fibroblast growth factor 5, connective tissue-derived growth factor, interleukin-11, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1, folistatin, ADAMTS1, and proteoglycan-1, all of which are overexpressed by at least four-fold when compared with the same cell line that has not metastasized to bone.14 Whilst much remains to be learnt about this diverse group of genes, it is understood that they encode for proteins with specific functions (eg, connective tissue growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 5 in angiogenesis, and interleukin-1 and osteopontin in osteolysis) that cooperatively promote successful cancer metastasis.14

Two of the many classes of proteins crucial for metastatic breast cancer in transit to bone are MMP and chemokines. MMP is a superfamily of at least 28 zinc-dependent proteinases that disintegrate the extracellular matrix.15 MMP-2 is the most studied in metastatic breast cancer. It cooperates with adhesion molecules, such as E-cadherin, resulting in invasion of the basement membrane.15 MMP-2 is also significantly increased in patients with HER2/neu gene-amplified tumors, suggesting MMP-2 as one signaling pathway for this aggressive tumor phenotype.15 Both MMP-2 and MMP-9 are associated with a poor prognosis in breast cancer when found at high levels.16,17 Chemokines, on the other hand, are small molecular cytokines essential for inducing chronic inflammation, tumor angiogenesis, and homing of tumor cells to target end-organs.18 Among the chemokine family, CXCR4 and C-C chemokine receptor type 7 are particularly important for breast cancer migrating to bone. CXCR4 and C-C chemokine receptor type 7 are receptors normally found on lymphocytes and stem cells, which enable these cells to transport high levels of their respective ligands, CXCL12 (also known as stromal cell-derived factor-1) and CCL21, to the organs, namely the liver, lung, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.18–20 In the same way, breast cancer cells also adopt this system by overexpressing CXCR4 and CCR7 receptors on their cell surfaces, thereby allowing them to “home in” on these end organs for metastasis.20 In fact, the CXCR4/SDF and CCR7/CCL21 axes are commonly manipulated by breast cancer bone metastases. CXCR4 receptor is expressed in 67% of breast cancer bone metastases with immunohistochemistry compared with 26% of nonbone metastases, whereas CCR7 is expressed exclusively in breast cancer bone metastases (27% versus 0%).21 Moreover, CXCR4 activation results in stimulation of the downstream mitogenic pathway (ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK]) and contributes to estrogen independence of the tumor.22 The connection between CXCR4, breast cancer proliferation, and bone metastasis has made CXCR4 an attractive therapeutic target. Multiple preclinical studies have now demonstrated the efficacy of CXCR4 antagonists in inhibiting bone metastases of breast cancer,23,24 and a recent Phase I/II clinical trial has also demonstrated preliminary signs of efficacy.25

Another pair of chemokine receptors exploited by breast cancer cells is CCR2 and CCR5, with their respective ligands, CCL-2 (also known as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 [MCP-1]) and CCL5, also known as RANTES (“regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted”). MCP-1 and RANTES are highly expressed in breast cancer cells, especially in the more advanced stages.26 They are responsible for recruiting deleterious tumor-associated macrophages, promote tumor-bone interactions, and angiogenesis (mainly via MCP-1).26 In addition, both bone marrow-derived and local stem cells can produce CCL5 in the bone microenvironment, further adding fuel to fame the effect of bone metastases.27,28 In short, cancer metastasis to bone is a structured and coordinated process that requires multiple steps, gene expression, and protein interactions. Therefore, it is likely that multiple pathways need to be targeted to reduce the occurrence of bone metastasis.

“Seed and soil” model of tumor engraftment

Although hematogenous dissemination and extravasation of cancer cells to secondary sites are efficient processes, the initiation and persistence of growth is relatively inefficient.13 Hence, optimal conditions for tumor cells to resettle are paramount after they have lodged in the bone microenvironment. Bone certainly has some unique qualities that favor tumor engraftment. Firstly, bone is a highly vascular organ. The axial skeleton contains large amounts of red marrow, which is demonstrated to have high blood flow.29 Secondly, bone susceptible to metastases is dysregulated in its acidity, intramedullary oxygen, and extracellular calcium levels. Thirdly, bone also harbors an abundance of growth factors, including TGF-β, IGF, hypoxic-inducing factor, interleukins, and chemokines, all of which are vital to cancer cell survival and proliferation. In essence, both the tumor and the host microenvironment contribute to the successful tumor engraftment from primary site to bone. Over 100 years ago, Paget described this phenomenon as the “seed and soil” model, where “the seeds (tumor) can only live and grow if they fall on congenial soil (an optimal microenvironment)”.30 Recently, Psaila and Lyden further expand on Paget’s original concept, and postulate the “metastatic niche” model, where the primary tumor prepares a “premetastatic niche” (the eventual site of bone metastases) by secreting a plethora of growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, placental growth factor, TGF-β, S100 chemokine, and serum amyloid A3, even before tumor migration.31 Once tumor has engrafted on the “metastatic niche”, a continuing supply of growth factors, particularly vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor, from the microenvironment, loss of death signals, and recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells, are necessary for the evolution of a tumor population from micrometastasis to macrometastasis.31 Thus, the symbiotic relationship between tumor and bone is pivotal to the settlement of metastases in new distant sites.

Osteolytic and osteoblastic metastases in bone

In cancer with bone metastases, the delicate balance between bone formation and resorption is disrupted. In osteolytic lesions, the bone resorption rate exceeds that of bone formation, whereas in osteoblastic lesions, the bone formation rate is faster. However, this occurs at the cost of quality of bone formation and organization, so the bone is flawed and fragile. Traditionally, breast cancer was recognized as the prototypic osteolytic tumor. However, this is a gross oversimplification. Only about 48% of bone metastases from breast cancer are purely osteolytic, with 38% being mixed osteoblastic and osteolytic, and 13% being purely osteoblastic.32 In fact, in bone metastases, both lytic and blastic processes are often accelerated. Histologically, there is evidence of resorption cavities even within sclerotic lesions. Biochemically, it has been observed that specific bone resorption markers are increased in bone metastases, irrespective of lytic or blastic radiological appearance.33 Therefore, osteolytic and osteoblastic changes are not opposing processes, but rather two distinct pathologies that frequently coexist.

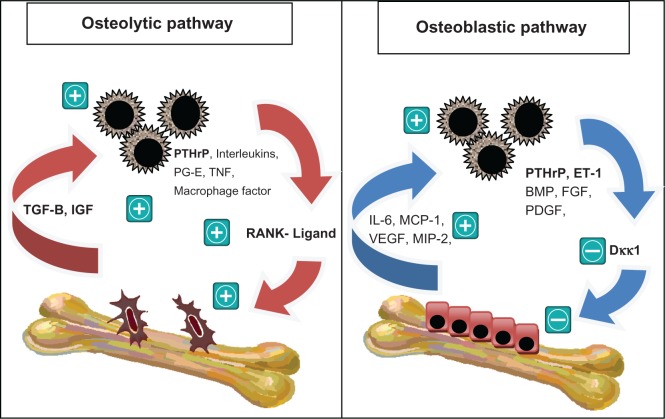

In the osteolytic tumor, tumor cells secrete parathyroid hormone-related protein and other factors, such as interleukins, prostaglandin E, TNF-β, and IGF-1, all of which are potent stimulators of osteoclastogenesis8,9 (see Figure 1). Parathyroid hormone-related protein is a crucial factor in breast cancer metastasis, with expression of 92% of breast cancer metastases in bone, compared with 60% of primary breast cancer, and only 17% of metastases at non-bone sites.34 Parathyroid hormone-related protein mediates its effect through the receptors on osteoblasts, which respond by upregulating RANK-L and macrophage-colony stimulating factor.35 This is accompanied by a downregulation of osteoprotegerin, resulting in a tilting of the RANK-L/osteoprotegerin ratio in favor of osteoclastogenesis.36 Indeed, breast cancer patients with bone metastases are more likely to express RANK in tumor cells and osteoclasts, and RANK-L in stromal cells and osteoblasts, compared with patients who do not have bone metastases or have been on bisphosphonates.37 Once osteoclasts are activated, they produce TGF-β, IGF-1, and other growth factors. TGF-β has a particularly significant role in tumorigenesis, because it is a potent stimulator of parathyroid hormone-related protein via Smad and the p38 MAPK signaling pathway.38 In addition, TGF-β activates signaling pathways similar to those of hypoxia by upregulating the CXCR4 and vascular endothelial growth factor gene pathway via hypoxic-inducing factor, to promote the feedforward metastatic cycle.39,40 In this way, the loop of bone destruction is complete, and it becomes a self-perpetuating cycle where the tumor and osteoclasts provide fuel for each other. There is certainly in vivo evidence that parathyroid hormone-related protein and TGF-β are crucial players in bone osteolysis.38,41 Targeted treatment, such as SD-208, a TGF-β receptor kinase I inhibitor, is being developed based on these models.42

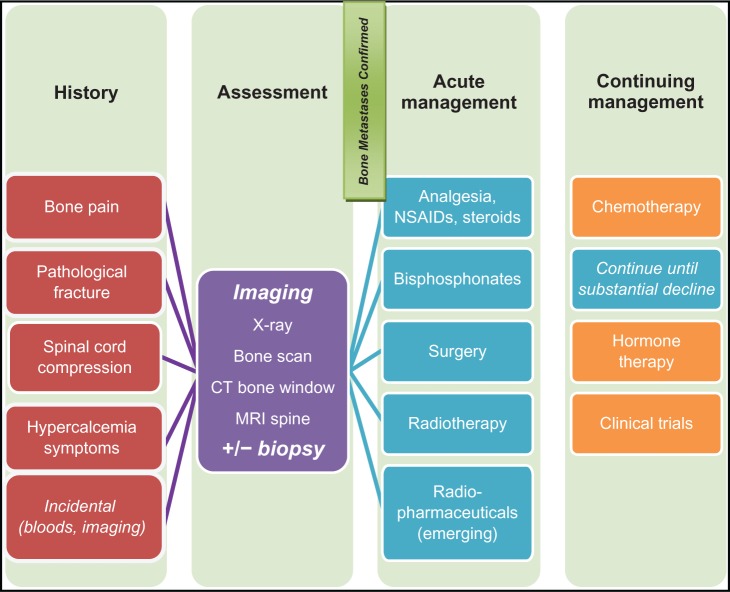

Figure 1.

The vicious cycle of bone metastases in the osteoblastic pathway, in which tumor cells secrete other factors (interleukins, prostaglandin e, tumor necrosis factor, and macrophage-stimulating factor). Parathyroid hormone-related protein induces osteoclastogenesis by upregulating the RANK ligand. The activated osteoclasts in turn produce transforming growth factor-beta and insulin growth factor which promote cancer cell growth. in the osteoblastic vicious cycle, breast cancer cells produce osteoblast-stimulating factors, such as bone morphogenic protein, fibroblast growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is also overexpressed. it activates endothelin-1, which downregulates Dickkopf-1, a negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis. The activated osteoblasts in turn produce factors including interleukin-6, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, vascular endothelial growth factor, MIP-2, which facilitate breast cancer cell colonization and survival upon arrival in the bone microenvironment. In reality, there is a complex interplay between the two cycles.8,9,42,43

Abbreviations: BMP, bone morphogenic protein; IGF, insulin growth factor; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; ET-1, endothelin-1; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; IL-6, interleukin-6; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; PG-E, prostaglandin E; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; MCP, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; TGF-B, transforming growth factor beta; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The osteoblastic pathway is less well studied, with research mostly focused on prostate cancer. Tumors produce many factors that stimulate osteoblasts, including endothelin-1, bone morphogenic protein, fibroblast growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor.43 The key factor appears to be endothelin-1 which, upon binding to the endothelin A receptor, suppresses Dickkopf-1, a negative regulator of the Wnt pathway.9 Studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between expression of Dickkopf-1 and osteoblastogenesis, which is independent of osteoclastogenesis.44,45 Parathyroid hormone-related protein is also paradoxically overexpressed in osteoblastic metastases. The theory is that parathyroid hormone-related protein is cleaved by various proteases, and the resulting NH2-terminal fragments also activate the endothelin A receptor42 (see Figure 1). The activated osteoblasts in turn produce factors, including interleukin-6, MCP-1, vascular endothelial growth factor, and MIP-2, which probably facilitate breast cancer cell colonization and survival upon arrival in the bone microenvironment.46 There is certainly in vivo evidence supporting a vicious osteoblastic cycle. Treatment with atrasentan, a selective endothelin-1A receptor antagonist (with no intrinsic antitumor properties), decreased osteoblastic metastasis and tumor burden in an animal model, suggesting that osteoblasts and tumor cells are closely linked.47 Further studies are required to elucidate this pathway.

In summary, bone metastasis formation involves a vicious cycle between tumor and bone, where one stimulates the other in a perpetual spiral of bone matrix distortion. This certainly occurs in osteolytic metastases, but probably also in osteoblastic metastases. In reality, there is a complex interplay between osteoblastic and osteolytic pathways. This is supported by the observation of 38% mixed osteolytic/osteoblastic lesions in breast cancer with bone metastases, as well as the evidence that bisphosphonates, which are potent osteoclast inhibitors, are effective in both osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions. Understanding the steps involved in the complex pathophysiology of bone metastases has helped to develop specific drug targets to break this vicious cycle.

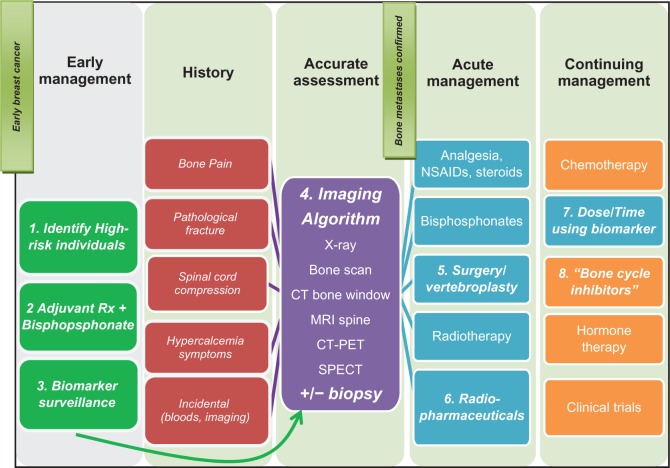

Optimal management of bone metastases in metastatic breast cancer

Preventing skeletal related events from established bone metastases

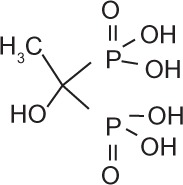

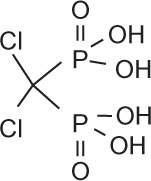

Bisphosphonates are an important class of therapeutics in reducing the frequency of skeletal-related events (30%–40%) and improving bone pain (50%),48 as well as being a recognized treatment for malignant hypercalcemia. Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclasts by inducing apoptosis of osteoclasts, and are therefore potent inhibitors of bone resorption. Once administered, bisphosphonates are rapidly cleared from the circulation and selectively bind to bone surfaces.49,50 Simple bisphosphonates, including clodronate, are converted intracellularly into methylene-containing analogs of ATP. This metabolite accumulates within macrophages and osteoclasts and causes direct apoptosis. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, including pamidronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid, inhibit farnesyl diphosphate synthase, a rate-limiting enzyme of the mevalonate pathway. Inhibition of farnesyl diphosphate synthase prevents protein prenylation of small GTPases, such as Ras, Rho, and Rab, which are important signaling proteins that regulate cell survival in osteoclasts.51,52 In vitro, at higher concentrations, nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates also inhibit osteoblasts, epithelial and endothelial cells, and breast, myeloma, and prostate tumor cells.52 This may explain, in part, the antitumor properties of potent nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, such as zoledronic acid. The potency, structure, and dosage of the bisphosphonates for metastatic breast cancer are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

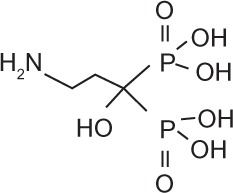

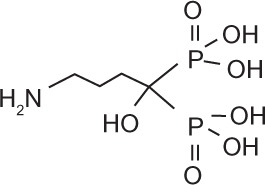

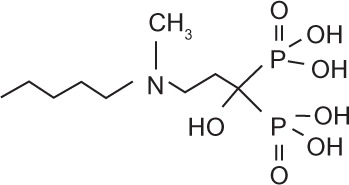

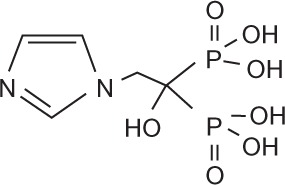

Bisphosphonates are defined by their P-C-P conformation, which renders them high affinity to the hydroxyapatite in bone mineral. Bisphosphonates contain two side chains, R1 being the variable structure that determines the potency of the compound (top left of each structure), and R2 being the short addition that increases the bone affinity (bottom left of each structure). Nitrogen-containing R1 improves the potency by at least 100-fold, and OH-containing R2 significantly increases the affinity to bone.

| Class | Simple bisphosphonate | Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Generic name | Etidronate | Clodronate | Pamidronate | Alendronate | Ibandronate | Zoledronic acid |

| Product name | Didronel® | Bonefos® | Aredia® | Fosamax® | Brondronat® | Zometa® |

| Relative Potency | 1 | 10 | 100 | 1000 | 10,000 | 100,000 |

| Dosage in MBC | Not indicated | 1600–3200 mg daily in single/divided dose | IV 90 mg 3–4 weekly |

Not indicated | PO 50 mg daily IV 6 mg monthly |

IV 4 mg 3–4 weekly |

Abbreviations: MBC, metastatic breast cancer; IV, intravenous; PO, oral.

Bisphosphonates have been clearly shown to reduce skeletal-related events in metastatic breast cancer. There have been in excess of 30 randomized controlled trials in the last 20 years evaluating clodronate, pamidronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid against placebo or against each other. The interpretation of an overall drug class effect by meta-analysis has proved challenging (see Figure 2), and is limited to studies reporting incidence rates. One of the problems has been in the definition of skeletal-related events, an aggregate endpoint, that encompasses complications of new bone metastases, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, irradiation of or surgery on bone, and development or progression of bone pain. In many of these trials, hypercalcemia was also included in the definition of a skeletal-related event.53 Because bisphosphonates are a well proven and highly effective treatment for malignant hypercalcemia, including this in the pooled skeletal-related event endpoint may bias results in favor of a positive treatment effect. Another problem has been the inconsistency in methodology chosen for reporting skeletal-related events. Some trials measured skeletal-related events using a surrogate endpoint of skeletal morbidity rate, defined as the mean number of skeletal-related events per year,54,55 or as the skeletal morbidity period rate, defined as the number of 12-week periods with new skeletal complications.56,57 Skeletal morbidity rate and skeletal morbidity period rate assume a constant event rate per patient in a given time period, and have been criticized because of failure to take into account the timing of events, resulting in unduly narrow confidence intervals (CI) and inflated false positive rates in treatment comparisons.58 More sophisticated models, such as the multiple event analyses model, could be used because this accounts for both timing and events.59 Given the limitations of these studies, pooled analysis of bisphosphonate trial data has proved an arduous task.

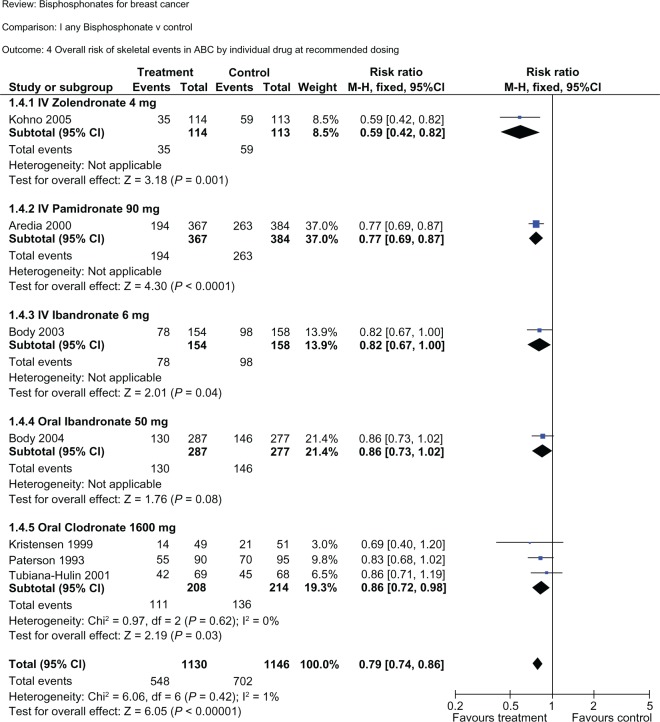

Figure 2.

Subgroup analysis of each bisphosphonate versus controls in reduction of the overall risk of skeletal-related events. All bisphosphonates decreased the overall risk of skeletal-related events, with a risk reduction of 41% for intravenous zoledronic acid, 23% for intravenous pamidronate, 18% for intravenous ibandronate, 14% for oral ibandronate, 16% for oral clodronate, resulting in a mean 21% risk reduction for all bisphosphonates combined. Note that in each subgroup the included trials are different. Therefore, conclusions about the relative efficacy between bisphosphonates cannot be extrapolated from this table. Note also that two intravenous pamidronate studies (Conte, Hultborn) were excluded from this subgroup analysis because they used less than the standard recommended dose of 90 mg. Reproduced with permission from © Cochrane Collaboration.53

To evaluate the role of bisphosphonates in metastatic breast cancer, data from 18 randomized controlled trials including in excess of 5600 patients were integrated in a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis.53 For women with advanced breast cancer and clinically evident metastases, bisphosphonates reduced the risk of developing skeletal-related events (excluding hypercalcemia) by 15% (95% CI 0.79–0.91, P < 0.00001). Bisphosphonates also significantly delayed time to skeletal events by 3–6 months. However, they did not reduce the incidence of new metastases (hazards ratio [HR] 0.99, 95% CI 0.67–1.47), nor affect survival in women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.93–1.05). Efficacy was demonstrated for both the oral and parenteral routes of administration, with a relative risk (RR) of 0.83 for intravenous bisphosphonate (95% CI 0.78–0.89) and 0.84 for oral bisphosphonate (95% CI 0.74–0.86). Individual drug effects on the RR of a skeletal-related event were 0.59 (intravenous zoledronic acid), 0.77 (intravenous pamidronate), 0.82 (intravenous ibandronate), 0.84 (oral clodronate), and 0.86 (oral ibandronate) compared with placebo (see Figure 2).

So which bisphosphonate is better? Rosen et al published a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial with a head-to-head comparison between 4 mg or 8 mg zoledronic acid and 90 mg pamidronate every 3–4 weeks for up to two years in metastatic breast cancer patients with bone metastases (n = 1130).60 Following a protocol modification due to concerns about renal toxicity with 8 mg zoledronic acid, the trial demonstrated noninferiority of 4 mg zoledronic acid to 90 mg pamidronate, with the on-study skeletal-related event rate (excluding hypercalcemia) being 43% for zoledronic acid and 45% for pamidronate. Using the multiple-event analysis model, this difference was shown to be significant for zoledronic acid (HR 0.801, P = 0.037). Within the lytic metastases subgroup (47% of patients), zoledronic acid yielded a significant prolongation of time to first skeletal-related event (310 versus 174 days, P = 0.013), significant reduction in skeletal morbidity rate (1.2 versus 2.4 events, P = 0.008), and a significant reduction in skeletal-related event rate of 30% (P = 0.010).61 Interestingly, the skeletal morbidity rate was significantly lower when zoledronic acid was combined with radiotherapy (0.47 versus 0.71 events, P = 0.018) or with hormone therapy (0.33 versus 0.58 events, P = 0.015), suggesting synergism between zoledronic acid and other antitumor therapies in preventing skeletal complications.60

Oral ibandronate has also been compared with intravenous zoledronic acid in a randomized Phase III study. Metastatic breast cancer patients with bone metastases were randomized 1:1 to receive oral ibandronate 50 mg daily versus intravenous zoledronic acid 4 mg monthly (n = 275).62 This was a biomarker study, with serum cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide type 1 collagen being the primary endpoint. Both bisphosphonates significantly reduced serum cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide type 1 collagen, with a 76% reduction in the ibandronate arm and a 73% reduction in the zoledronic acid arm. There was a similar reduction in other bone turnover markers with the two treatments. There were fewer adverse events in the ibandronate arm, with less treatment-related pyrexia (0% versus 16.8%), influenza-like symptoms (0.7% versus 5.1%), musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (11% versus 20.4%), and headaches (2.2% versus 11%). Importantly, there was no evidence of deterioration in renal function in either group. Skeletal-related events were not measured as an endpoint in this study. A Phase III trial comparing zoledronic acid and ibandronate (Zoledronic acid versus oral Ibandronate Comparative Evaluation [ZICE]), with skeletal-related events as the primary endpoint, is underway in the UK and scheduled for completion in 2011.63

Current treatment guidelines are summarized in Table 2. Selecting which bisphosphonate to use needs to be individualized, and the decision is likely to be influenced by the additional benefit of some bisphosphonates in reducing bone pain, their convenient administration, toxicity profiles, and drug accessibility (Table 3).

Table 2.

Existing guidelines/recommendations for bisphosphonates regarding use in metastatic breast cancer patients with bone metastases

| When to start? | Which bisphosphonate? | When to stop? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASCO guidelines 201170 | Breast cancer + radiographic evidence of bone destruction: • Lytic disease on x-ray • Abnormal bone scan with CT/MR showing bone destruction Starting bone modifying agents in women with abnormal bone scan in the absence of bone destruction in X-ray/CT/MR is not recommended. |

• IV PAM 90 mg every 3–4 weeks OR • IV ZOL 4 mg every 3–4 weeks OR • SC DMB 120 mg every 4 weeks |

Once initiated, to continue until evidence of substantial decline in patient’s general performance status |

| International expert panel guidelines 200866 | MBC + first sign of radiographic evidence of bone metastases, even if patient is asymptomatic | Nitrogen-bisphosphonate • IV preferable (ZOL, IBA, PAM) • PO for patients who cannot or need not attend hospital care (CLO, IBA) |

Continue beyond 2 years but always based on individual risk assessment; should not discontinue treatment once SRE occurs |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MR, magnetic resonance; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; PO, oral; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; SRE, skeletal-related event; ZOL, zoledronic acid; IBA, ibandronate; PAM, Pamidronate; CLO, clodronate; DMB, denosumab.

Table 3.

Individualizing bisphosphonate for the patient. Consideration of both benefits and adverse effects are both important in decision-making

| PO clodronate | PO ibandronate | IV Pamidronate | IV ibandronate | IV zoledronic acid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevents SRE53,61 | ↓16% (heterogeneity in 3 trials P = 0.021) | ↓14% | ↓23% | ↓18% | ↓4l%(ZOL>PAM) |

| Manages bone pain71 | – | ++ Sustained >96 weeks Better QOL (↑30%) |

++ Sustained >96 weeks QOL = placebo |

++ Sustained >96 weeks Better QOL (↑20%) |

++ Sustained >52 weeks Better QOL (↑5%) as Second-line agent |

| Treats hypercalcemia72 | – | – | ++ (duration of effect 3–4 weeks) | – | ++ (duration of effect 4–6 weeks) |

| Convenience73 | Oral daily | Oral daily | 90 minutes monthly | 1–2 hours monthly | 15 minutes monthly |

| Esophagitis56,74 | Not reporteda | 2.1% vs 0.7% (ibandronate vs placebo)b | Not related to IV bisphosphonate | Not related to IV bisphosphonate | Not related to IV bisphosphonate |

| Renal toxicity56,60,73,75 | Not reporteda | Noneb (Not significantly different to placebo) |

8.2%d CrCI 30–60: infuse over 4 hourse CrCI < 30: No PAMe |

Nonec (Not significantly different to placebo) |

8.9%d CrCI 50–60: 3.5 mge CrCI 40–49: 3.3 mge |

| Dose adjustment for renal toxicity | CrCI 30–50: 6 mg alternate daysc CrCI < 30: 6 mg weeklyc |

CrCI 30–50: 4 mge CrCI < 30: 2 mge |

CrCI 30–39: 3 mge CrCI < 30: No ZOLe |

||

| ONJ(~1%)Δ68 | Not reporteda | Largely unknown; 0.3% of ONJ due to oral ibandronatef | Cumulative risk 0% 1st year, 4% 3rd year; 31% of reported ONJ due to Pamidronatef | Largely unknownf | Cumulative risk 1% 1st year, 21% 3rd year; 35% of reported ONJ due to zoledronatef |

Notes:

Early studies between oral clodronate and placebo not informative of specific GIT toxicities, and the best data come from the adjuvant trial by Powles et al74 where there is no significant difference in nausea and vomiting between clodronate and placebo, but significandy higher rate of diarrhea (16%) in clodronate arm versus placebo arm (7%, P < 0.001). Oesophagitis, renal toxicity or ONJ were not studied in the clodronate trials, metastatic or adjuvant;

Study between PO ibandronate and placebo: esophagitis reported in 2.1% in 50 mg PO ibandronate vs 0.7% in placebo arm, dyspepsia in 7.0% in ibandronate arm vs 4.7% in placebo arm., renal toxicity 5.2% in ibandronate arm versus 4.7% in placebo arm (NS);56

Study between IV ibandronate and placebo, renal toxicity defined by Cr > 300 mM reported in 2.6% in 6 mg IV ibandronate, 0.7% in 2 mg IV ibandronate and 1.3% in placebo arm (NS);75

Study between Pamidronate and zoledronic acid, renal toxicity rate similar after amendment from 8 mg zoledronic acid to 4 mg, renal impairment is defined by at least twice the baseline value, or ≥0.5 mg/dL change from baseline for patients with baseline Cr ≤ 1.4 mg/dL, or ≥ 1.0 mg/dL change from baseline for patients with baseline Cr ≥ 1.4 mg/dL;60

The following recommendations are from the package insert information from MIMS Australia;73

Osteonecrosis of the jaw is rare (< 1%). It is associated not only with the specific bisphosphonate, but also the cumulative dose, as well as recent dental surgery, dental pathology, and trauma. Pamidronate and zoledronate is well studied as a trigger for ONJ, but there is a paucity of data on ibandronate and ONJ. Dark grey: most effective or preferred; Grey: most harmful or highest risk.68

Abbreviations: PO, oral; IV, intravenous; ZOL, zolendronic acid; CrCI, creatinine clearance; PAM, Pamidronate; QOL, quality of life; SRE, skeletal-related events; ONJ, osteonecrosis of the jaw.

When to start a bisphosphonate and when to stop? There is controversy in both areas due to a paucity of data specifically addressing this question. In the exploratory retrospective analysis of the Rosen et al trial of pamidronate versus zoledronic acid, patients who already had one prior skeletal-related event were found to be at significantly higher risk of developing an on-study skeletal-related event than patients with no prior skeletal-related event, with an HR of 2.08.64 This suggests that waiting for a skeletal-related event to occur may be detrimental for patients with bone metastases. As such, both the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines and the International Expert Panel guidelines recommend starting bisphosphonates at the first radiographic sign of cancer in bone.65,66 As for the duration of bisphosphonate treatment, there are currently few data on the efficacy and safety of bisphosphonates beyond two years. There are certainly some concerns about prolonged use of bisphosphonates, regarding their overall cost-effectiveness, impact on quality of life (particularly with monthly infusions), and the theoretical concept of “frozen bone”, where prolonged use of high-dose bisphosphonates in animal models has been found to increase microdamage and decrease bone toughness.67 This pathology is thought to be the underlying mechanism of osteonecrosis of the jaw, the risk of which increases with the cumulative dose of bisphosphonate, especially with zoledronic acid and pamidronate.68 Currently, the bone tumor response to therapies is assessed by imaging at the discretion of the treating oncologist every 2–6 months, with changes on bone scan and x-ray seen within 3–6 months, and changes on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging seen within two months.69 In the future, new biochemical markers may detect changes earlier, and help to select patients for dose adjustment and continuation beyond two years.

Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANK-L, has been shown preclinically and in clinical trials to inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone destruction.76 In a Phase II trial that randomized breast cancer, prostate cancer, and multiple myeloma patients to zoledronic acid or denosumab, denosumab demonstrated superior suppression of the bone turnover marker, urinary N-telopeptide, compared with zoledronic acid (71% versus 29%, with a urinary N-telopeptide < 50 nM).77 A recently published controlled Phase III trial included 2064 breast cancer patients from 322 centers with bone metastases who were randomized to subcutaneous denosumab 120 mg or intravenous zoledronic acid 4 mg every four weeks. This noninferiority trial actually established superiority of denosumab in delaying the time to first on-study skeletal-related event over zoledronic acid (HR 0.82, P = 0.01), as well as reducing the risk of developing multiple skeletal-related events (RR 0.77, P = 0.001). While the total rate of side effects was similar between both groups, denosumab was associated with less renal toxicity (4.9% versus 8.5%, P = 0.001) and fewer acute-phase reactions (10.4% versus 27.3%). The rate of osteonecrosis of the jaw was not significantly different between denosumab and zoledronic acid (2.0% versus 1.4%, P = 0.39).78 This improved efficacy with denosumab, along with the convenience of administration and the more favorable renal effect profile, is expected to result in the addition of denosumab to the armamentarium of treatment for breast cancer with bone metastases.

Managing bone pain as an established skeletal related complication

Intractable bone pain occurs in 50%–90% of metastatic breast cancer patients with bone metastases, with up to 54% receiving short-term pain relief with treatment.79,80 The pathophysiology of bone pain is unique when compared with inflammatory pain or neuropathic pain, in that there is substantial spinal cord astrocytosis, enhanced neuronal activity through c-Fos expression, and sensitization of the central dorsal horn of the spinal cord mediated by dynorphin, a prohyperalgesic peptide.81 It is believed that both tumor-induced damage (bone destruction, pathological fracture, tissue infiltration, secondary muscle spasm, nerve compression) as well as tumor-produced factors (endothelin-1) have important roles in the generation of bone pain.43 Bone pain is generally poorly localized, with a deep boring and aching quality, and episodes of stabbing discomfort. It is particularly worse at night, and is not necessarily helped by lying down or sleeping.33,79 Current therapies focus on adequate pain control using anti-inflammatory corticosteroids and opioids, slowing down osteolysis with bisphosphonates, reducing tumor burden with radiotherapy, and stabilizing bones surgically, or with radiopharmaceuticals in selective cases.81,82

There are several trials that have examined the use of bisphosphonates to treat bone pain, but interpretation of the trial results for bone pain has been difficult, because of inconsistency in pain definition, its measurement and timing, and lack of standardized recording of analgesic use.83 A meta-analysis specifically examining bisphosphonate effects on bone pain was published in 2002.84 It included 30 well conducted trials that encompassed breast, prostate, lung, multiple myeloma, and cancer of unknown primary. The bisphosphonates studied were etidronate, pamidronate, and clodronate. The pain relief benefit is certainly appreciated in metastatic breast cancer patients (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.11–3.04). In the subgroup analysis, the response is significant for oral clodronate (HR 3.26, 95% CI 1.80–5.09), but not for intravenous pamidronate (HR 2.35, 95% CI 0.77–7.15), and the trend is unfavorable for etidronate (HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.01–7.67). However, Lipton analyzed two pivotal trials (one with chemotherapy, another with hormone therapy, total n = 751), where pamidronate significantly reduced the pain score (−0.07, P = 0.015) and the analgesia score (−0.06, P = 0.001) at 24 months.55 Other new potent nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates also show promise in this field. There are at least three randomized studies that substantiate the significant and sustained pain relief afforded by zoledronic acid, and one study also improved quality of life.71 Furthermore, a Phase II study has demonstrated the feasibility of using zoledronic acid as a second-line agent for patients who have failed on pamidronate or clodronate.85 Ibandronate is probably the best studied in the bone pain literature, having utilized the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire, pain scale (0–4) and analgesia consumption questionnaire (0–5) in all three studies (two oral and one intravenous). Both oral and intravenous ibandronate were shown to reduce bone pain, peaking within 8–12 weeks and persisting for at least 96 weeks. In addition, patients on intravenous ibandronate had improved quality of life.86,87 Thus far, oral clodronate, intravenous pamidronate, intravenous zoledronic acid, and oral/intravenous ibandronate have all demonstrated bone pain relief, with ibandronate showing the longest time of sustained pain relief (96 weeks). Intravenous zoledronic acid also showed an advantage as a second-line agent in a Phase II trial, whilst oral/intravenous ibandronate has the best evidence for improvement of quality of life.

Radiotherapy is an established treatment for bone pain from metastases, and is also used to treat pathological fractures and neurological complications. External beam radiotherapy can achieve pain relief within 4–6 weeks, and retreatment is possible if pain recurs.88 Multiple fractions (20 Gy/5 fractions) were equivalent to a single fraction (8 Gy/1 fraction) in achieving an overall response (59% versus 58%, 95% CI 0.95–1.03), but the retreatment rate was 2.5-fold higher in the single fraction arm (P < 0.00001).89 For patients with multifocal bone metastases, half-body irradiation has been shown to produce prompt pain relief (1–4 weeks) at the cost of acute toxicity (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea in first 24–48 hours), although there was no correlation between field size and pain relief.90 The analgesic mechanism of radiotherapy is incompletely understood. Whilst radiotherapy certainly mediates some analgesic effect via tumor debulking, there is also evidence pointing towards osteoclast inhibition.91 Given the potential overlap of the mechanisms of radiotherapy and bisphosphonates, and availability of in vivo evidence, there is growing interest in combining the two treatments for synergistic effect.88,91 More recently, bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals have been developed for palliation of refractory bone pain. These are thought to act as a substitution for the hydroxyapatite of bone, with more uptake in osteoblastic metastases where new reactive bone is formed. The response takes 2–3 weeks to develop after administration and lasts for 3–6 months, with response rates of 55%–95% and complete relief in 5%–20%. The main toxicity is flare reaction in 10% of patients and Grade 2 or less myelosuppression.92 Whilst the evidence is more established in metastatic prostate cancer, there have been a few small relevant studies in metastatic breast cancer.93 One study involving 100 patients (60 with metastatic prostate cancer, 40 with metastatic breast cancer) randomized to strontium or samarium shows improvement in Karnofsky status (+20) and reduction in pain by visual analog scale (−4), with more favorable results for osteoblastic than mixed metastases.94

Managing other established skeletal-related complications

Other skeletal-related complications are equally important, because pathological fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression occur in 35%, 19%, and 8% of cases, respectively.95 A team approach with experienced surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and palliative care physicians is often necessary. Spinal cord compression, in particular, is a medical emergency. Symptoms include motor weakness (96%), pain (94%), sensory disturbance (79%), and sphincter disturbance (61%).96 The key to management is high-dose steroids, urgent radiology (magnetic resonance imaging), and prompt referral for surgical decompression and/or radiotherapy. In the randomized landmark trial by Patchell et al, surgery followed by radiotherapy demonstrated a significantly better post-treatment ambulatory rate (84% versus 57%, P < 0.001) compared with radiotherapy alone, with a significant prolonged continence rate (odds ratio [OR] 0.47, P = 0.016), functional ability (OR 0.24, P = 0.0006), and motor strength (OR 0.28, P = 0.001). In fact, survival time is also significantly better in the combined modality group (126 days versus 100 days, OR 0.60, P = 0.033).97 That being said, patients with very radiosensitive tumors, multiple areas of spinal cord compression, or total paraplegia for longer than 48 hours, were excluded from the study. Given the selection bias of this trial and the controversy concerning the optimal radiotherapy regimen, surgery should be offered as upfront treatment for fit and functional patients with spinal cord compression, while radiotherapy is best reserved for the unfit, already incapacitated, or those with poor prognosis.

Role of effective systemic endocrine and chemotherapy

Effective systemic treatment is paramount not only for breast cancer bone metastases, but also for metastatic breast cancer in general. Chemotherapy is certainly an important part of systemic treatment, with good clinical evidence supporting anthracyclines and taxanes as key initial treatments, ie, capecitabine + docetaxel, liposomal doxorubicin, aza-epothilone B (ixabepilone), and various other chemotherapies reserved for after failure on anthracyclines and/or taxanes.98–103 Evidence is mounting for the role of endocrine therapy, specifically for breast cancer with bone metastases. It has been observed that, among patients with recurrent breast cancer, those who previously had estrogen receptor-positive tumors are twice as likely to develop bone metastases than those who had estrogen receptor-negative tumors.104 Microarray studies in breast cancer patients have provided further proof that bone metastases occur far more frequently in estrogen receptor-positive tumors (luminal types A and B, 68%), compared with HER2-positive tumors (20%), basal tumors (7%), and normal molecular subtypes (6%).105 Of note, the genes upregulated for estrogen receptor-positive bone metastases are entirely different from those for HER2-positive or basal subtype bone metastases.105 This suggests that the estrogen receptor is involved in distinct molecular pathways that endow estrogen receptor-positive tumors with the ability to metastasize to bone. Indeed, estrogen receptor signaling has now been shown to coactivate with various cofactors, such as steroid receptor coactivator 1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor binding protein, induce a myriad of micro-RNAs at the nuclear level, and cross-talk with other tyrosine kinase receptors, including epidermal growth factor, HER2, and the IGF-1 receptor.106 While endocrine therapy is already a well established treatment for metastatic breast cancer patients in multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses,107–113 understanding the relevant pathways involved may provide a further rationale for its use, particularly in the setting of bone metastases. In fact, current guidelines recommend endocrine therapy in preference to chemotherapy for women with hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer, except in the presence of rapidly progressive visceral disease, given the lower toxicity of endocrine therapy, similar overall survival when compared with chemotherapy, and slower progression of cancer in patients with endocrine-responsive disease.114,115 Therefore, for the majority of patients with new bone metastases who have estrogen receptor-positive HER2-negative luminal-type breast cancer, it may be reasonable to start with endocrine therapy (a third-generation aromatase inhibitor over tamoxifen for postmenopausal women, given the higher overall response and longer progression-free survival) and a bisphosphonate, particularly if the patient has had a long disease-free interval (more than two years), limited visceral recurrence, and slowly progressive disease.114,116

Preventing bone metastases in early breast cancer

Preclinical evidence of antitumor properties of bisphosphonates

The antitumor properties of bisphosphonates have been examined in vitro, with bisphosphonates shown to inhibit tumor adhesion and invasion, induce tumor apoptosis, and exert an antiangiogenic effect. This evidence is especially strong for nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates.117 In vivo, bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce tumor burden and prevent new bone metastases, in a dose-dependent fashion.118 Some bisphosphonates (predominantly zoledronic acid) exhibit extraskeletal antitumor activity. Repeated injection of zoledronic acid was shown to decrease liver and lung metastases, as well as to improve survival in a murine model. The mechanism of this effect is thought to relate to its inhibition of cell migration and invasion, and induction of apoptosis in breast cancer cells.119 Bisphosphonates may also have immunomodulatory effects, given that continuing activation of γδ effector T cells has been demonstrated after a single dose of zoledronic acid in an ex vivo model of disease-free breast cancer patients.120 The synergism between zoledronic acid and chemotherapy may also be sequence-specific and schedule-specific. Zoledronic acid causes a 10-fold increase in tumor apoptosis in vitro when administered 24 hours after doxorubicin, mediated by inhibition of the mevalonate pathway, possibly because cells sensitized by chemotherapy facilitate uptake of bisphosphonates, leading to G2/M phase cell cycle arrest.121 This hypothesis is being tested in a neoadjuvant setting in the randomized Phase II ANZAC (zoledronic acid 24 hours after 5-fluorouracil-epirubicin-cyclophosph-amide) study, and it may have important implications for dose scheduling of bisphosphonates in the future.117

Clinical evidence in adjuvant breast cancer trials

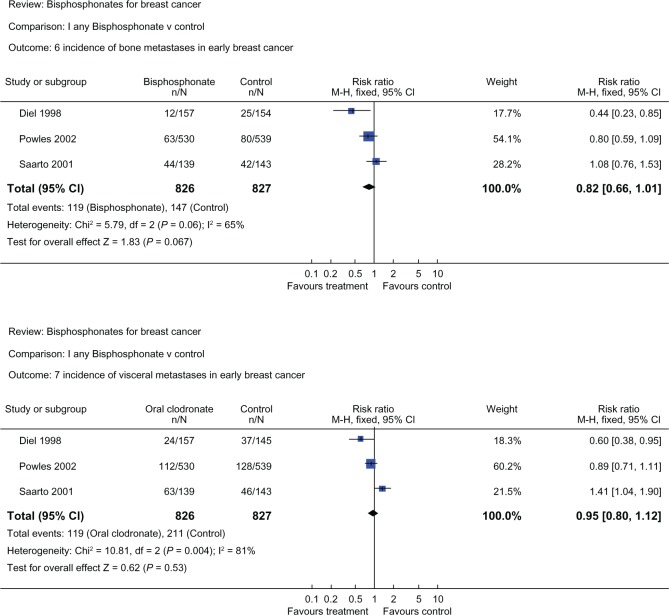

Three randomized trials commenced in the 1990s explored the use of clodronate in the adjuvant setting for early breast cancer patients. Diel et al randomized 302 patients with detectable tumor cells in bone marrow to 1600 mg clodronate daily for two years or to no clodronate treatment,122 Saarto et al evaluated the use of clodronate for three years in 299 high-risk node-positive patients,123 and Powles et al published the largest cohort involving 1069 patients randomized to two years of clodronate or placebo.74 The study endpoints were incidence of distant metastases (bone, visceral, local, nonskeletal) and overall survival. The comparison of the three trials is illustrated in Table 4. These trials produced quite discordant results. Bone metastasis-free survival and nonskeletal-free survival were most favorable for clodronate in the Diel et al study, less favorable in the Powles et al study, and unfavorable in the Saarto et al study. Similarly, for patients on clodronate, overall survival was considerably improved for the Diel et al study (HR0.50, P = 0.049),124 was improved in the Powles et al study (HR 0.74, P = 0.041),125 and was worse in the Saarto et al study (HR 1.33, P = 0.13).123 The discrepancy in these trials may be explained by variability in sample size, study populations, and study methodology. In the Saarto et al trial, there is imbalance of baseline characteristics between treatment arms, including estrogen receptor-negative subgroup (35% in clodronate group and 23% in control group) and postmenopausal women (52% in the clodronate group and 43% in the control group). Also, post-menopausal women were given endocrine therapy but not chemotherapy in this study.126 Although heterogenous, these trials, when analyzed together, produce a nonsignificant trend favoring clodronate for bone and visceral metastases (Figure 3).53 In an updated meta-analysis in 2007, the overall survival (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.31–1.82), bone metastasis-free survival (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.38–1.23), and nonskeletal metastasis-free survival (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.40–1.98) remain favorable but nonsignificant for clodronate.127 Results from the large National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project 34 (NSABP-B34) trial (3323 Stage I–III breast cancer patients on chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy, randomized to adjuvant clodronate or placebo for three years) are eagerly awaited.

Table 4.

Comparison of the three clodronate trials. Although all three trials tested two years of clodronate 1600 mg/day against placebo, the study populations are quite different. This may result in variability in the results

| Diel et al124 | Powles et al125 | Saarto et al123 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 302 | 1069 | 299 |

| Age | 51 | 53 | 52 |

| Menopausal status | Pre- and post- | Pre- and post- | Pre- and post- |

| Nodal status | N0 and N+ | N0 and N+ | N+ |

| Adjuvant therapy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bone marrow micromets | Yes | No | No |

| Clodronate dose | 1.6 g PO | 1.6 g PO | 1.6 g PO |

| Duration of treatment | 2 years | 2 years | 3 years |

| Follow-up time to-date | 8.5 years | 5.6 years | 10 years |

| Intent-to-treat analyses | ?Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bone recurrence (HR)a | 0.90 (P = 0.770) | 0.692 (P = 0.043) | 1.23 (P = 0.35) |

| Visceral recurrence (HR)a | 0.95 (P = 0.222) | 0.84 (P = 0.241) | 1.61 (P = 0.015) |

| Death (HR)a | 0.50 (P = 0.049) | 0.743 (P = 0.041) | 1.33 (P = 0.13) |

Notes:

Hazard ratio (HR) less than 1 is in favor of treatment for preventing the specified outcome. HR more than 1 is against the treatment preventing the specified outcome. P value of less than 0.05 (in bold) is considered statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of clodronate trials. Overall, clodronate shows a trend in decreasing bone metastases, and less so for visceral metastases. Both results are nonsignificant and there is a high level of heterogeneity (l2 = 65% and 81%, P = 0.06 and 0.004 for bone and visceral metastases respectively). Reproduced with permission from © Cochrane Collaboration.53

Adjuvant zoledronic acid has also been evaluated for early breast cancer. The first report came from the Austrian Breast Cancer Study Group (ABCSG-12). In this study, 1803 premenopausal patients with Stage I or II hormone-positive breast cancer and on monthly goserelin were randomized in a two by two factorial design to receiving either tamoxifen or anastrazole, with or without zoledronic acid 4 mg every six months, for a duration of three years and a median follow-up of four years.128 Whilst the study was underpowered to demonstrate a disease-free survival or recurrence-free survival difference between the endocrine therapies tamoxifen and anastrazole (P = 0.59 and P = 0.53, respectively), there was in fact a 36% improvement in disease-free survival (absolute difference 3.2%) for patients on zoledronic acid (P = 0.01). Overall survival was not significantly different, but there was a trend favoring zoledronic acid (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.32–1.11, P = 0.11). Of note, the benefit was not limited to skeletal events, but applied to all distant metastatic sites and locoregional recurrence rates. A direct antitumor effect of zoledronic acid seems an unlikely explanation for this, given the infrequent six-monthly dosing. A more plausible explanation may be the inhibitory effect of zoledronic acid on dormant tumor cells in the bone marrow.129 Furthermore, the ABCSG-12 bone mineral density (BMD) sub-study (n = 404) shows that 2 years after completion of treatment, patients who received zoledronic acid had increased BMD (+4% at lumbar spine, P = 0.02), whereas patients who had not received zoledronic acid still had decreased BMD (−6.3% at lumbar spine, P = 0.001).130 Another intriguing trial is the parallel Zometa®-Femara® bone loss prevention research (Z-FAST, ZO-FAST), where 2195 postmenopausal women receiving five years of letrozole are randomized to early zoledronic acid (beginning of the study) or delayed zoledronic acid (when T score is ≤ 2.0 or an osteoporotic fracture had occurred). When commenced, zoledronic acid was given every six months for up to five years. Likewise, in both Z-FAST and ZO-FAST, BMD improved in the early treatment group and decreased in the delayed treatment group, with the absolute difference in mean lumbosacral and total hip BMD of +6.7% and +5.2% favoring the early treatment group at a 36 month follow up in Z-FAST (P < 0.001), and mean L2-L4 BMD of +9.29% also favoring the early treatment group at 36 months in ZO-FAST (P < 0.001).131,132 Moreover, in a combined interim analysis of Z-FAST and ZO-FAST at 12 months, disease recurrence was less in the early treatment group than in the delayed treatment group (7 events vs 17 events, P = 0.0401).133 This difference was upheld in the ZO-FAST study at 36 months (26 versus 43 events, P = 0.0314), corresponding to a relative risk reduction of 41% and an absolute difference of 3.2% disease-free survival improvement.131 The benefit, like in the ABCSG-12 trial, was seen in both local recurrence (0.4% versus 1.9%) and distant recurrence (3.8% versus 5.6%). The Z-FAST study also reports a smaller number of disease recurrence rate between early and delayed treatment group (3.0% vs 5.3%) at 36 months follow up, but the result is not significant (P = 0.127).132

AZURE (the Adjuvant Zoledronic Acid to redUce Recurrence trial) is one of the largest zoledronic acid trials, and randomized 3360 patients from 174 centers to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy ± zoledronic acid 4 mg intravenously every 3–4 weeks for six doses, then three-monthly × 8 and 6-monthly × 5 to complete five years of treatment. In an exploratory analysis of the AZURE trial, comprising neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without an intensive zoledronic acid schedule (n = 205), there was a significantly improved pathological complete remission rate (10.9% versus 5.8%, P = 0.033) and residual invasive tumor size (28.2 mm versus 42.4 mm, P = 0.002) in the zoledronic acid chemotherapy combination.134

However, in the second interim analysis of the AZURE trial, with a median follow-up of 59 months, there was equivalent disease-free survival in both the zoledronic acid and control groups (377 versus 375 events, HR = 0.98, P = 0.79).135 It is difficult to understand the conflicting results between the ABCSG-12 and AZURE trials, but there are differences in the trial designs (Stage I/II in ABCSG-12 versus Stage II/III in AZURE), additional adjuvant treatments (no adjuvant chemotherapy in ABCSG-12 versus 96% patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy in AZURE) and in patient selection (all premenopausal in ABCSG-12 versus only 35% premenopausal in AZURE) that may help explain the disparate results.128,136 Interestingly, in the AZURE trial, in a subgroup of women (n = 1101) who had more than five years of menopause, overall survival was improved by 21% (HR 0.71, P = 0.017). In general, subgroup analyses need to be interpreted cautiously, but this does generate the interesting hypothesis that zoledronic acid may manifest higher antitumor activity in a microenvironment with a low estrogen level. This may explain why the trial result was positive in the ABCSG-12 trial, which involved premenopausal women, all with menopause artificially induced by goserelin.136 That said, given the negative result in the AZURE trial, zoledronic acid currently cannot be recommended as a standard adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. The results from the SUCCESS trial (3754 Stage I–III breast cancer patients on sequential third-generation chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy, randomized to zoledronic acid for two years or five years) may shed some light on the role of adjuvant zolendronate in the near future.129

New advances in management of breast cancer bone metastases

From the 1990s to the last decade, there has been a transformation in both our perception and approach to treatment of bone metastases in breast cancer. It has changed from a very high prevalence of skeletal-related events of 80% (1975–1991) to 50% (1999–2007).95,137 It has also changed from a much feared comorbidity to a manageable complication, and it has changed from reactive palliative management with analgesia, surgery, and radiotherapy, to pre-emptive management with bisphosphonates to prevent skeletal-related complications. In the last 10 years, there has been an explosion of knowledge about the pathophysiology of bone metastases in breast cancer, particularly through a plethora of preclinical studies and translational research. The next 10 years is going to witness an evolution in the management of bone metastases, heading towards therapies focusing specifically on the very mechanism of bone metastases, as well as utilization of biomarkers to guide therapy.

Novel “bone cycle” inhibitors

Gene expression profiling and subculturing of cell lines that metastasize to bone have paved the way for understanding the pathophysiology of bone metastases.138 Having discovered the “vicious cycle” of bone metastases, scientists have started to design novel agents specifically targeting these pathways. Many of these compounds are already being tested in clinical trials (Table 5). The first of this class of drugs to succeed in Phase III randomized controlled trials is denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against the key factor, RANK-L, in an osteoclast-mediated vicious cycle.139 Recently, denosumab has shown superiority over zoledronic acid in delaying skeletal-related events in both metastatic breast cancer (HR 0.82, P = 0.01) and prostate cancer (HR 0.82, P = 0.0002).78,140 Denosumab is administered subcutaneously 120 mg once a month. As discussed previously, it has fewer acute-phase reactions, such as fever, myalgia, or arthralgia, and does not need renal monitoring, although hypocalcemia occurs more frequently than for zoledronic acid.78

Table 5.

Novel agents in development with specific targets on the “vicious cycle” of bone metastases. Some of these agents have entered the Phase III trial setting8,42,138,140,143,144,148–150

| Drug | Target | Mechanism of action (of target) | Stage of development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor of osteoclast differentiation | |||

| Denosumab (AMG 162) | Humanized AB to RANK-L | Osteoclast activation and survival | Phase III positive (breast CA) Phase III positive (prostate CA) |

| Inhibitor of osteolytic “vicious cycle” | |||

| CAL | Antibody to PTHrP | Tumor activation of osteoclast | Phase I |

| GC-1008 | Inhibitor of TGF-β R1, 2, 3 | Osteoclast activation of tumor | Phase II (mesothelioma) ongoing Observational (renal, melanoma) |

| AP-12009 (trabedersen) | Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide specifically directed against TGF-β2 mRNA | Osteoclast activation of tumor | Phase I/II (pancreatic, melanoma, CRC) completed Phase III anaplastic astrocytoma ongoing |

| Inhibitor of osteoclast signal transduction | |||

| SB203580 | Inhibitor of P38 MAPK | Produces IL-1 and TNF which activates osteoclast | In vivo data completed |

| Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibitor | Promotes osteoclast differentiation through nuclear NF-κB | In use in multiple myeloma |

| Inhibitor of enzymatic activity | |||

| Saracatinib (AZD-0530) | Dual Src/abl kinase inhibitor | Form ruffled border of osteoclast; crosstalk with multiple pathways (HER2, ER) | Phase II (breast and prostate CA) ongoing |

| Dasatinib | Non-specific inhibitor of Src (also inhibits Bcr-abl, c-kit, PDGFR-beta, ephA2) | Form ruffled border of osteoclast; cross-talk with multiple pathways (HER2, ER) | Phase II (breast CA): 2 completed, 3 ongoing, in use in CML |

| Odanacatib (MK-0822) | Inhibitor of cathepsin K | Breakdown of collagen in bone | Phase II (breast CA), completed |

| Inhibitor of cell-matrix interaction | |||

| SC56631 | Vitronectin receptor, an αvβ3 integrin | Allows osteoclasts adhere to bone surface | Phase I |

| Chemokine inhibitor | |||

| CTCE-9908 | Inhibitor of CXCR4 | Prevents tumor migration to bone | Phase I/II completed |

| Endothelin inhibitor | |||

| Atrasentan (ABT-627) | Inhibitor of endothelin A receptor | Stimulates osteoblast proliferation | Phase III (prostate CA) |

| Chemotherapy: microtubule stabilizer | |||

| Sagopilone | Microtubule stabilizer/epothilones (like taxane) | Inhibits tumor growth and bone resorption | In vivo, ex vivo completed Phase II (breast CA) completed |

Abbreviations: AB, antibody; CA, carcinoma; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; ER, estrogen receptor; IL-1, interleukin-1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta.

Another important class is the TGF-β inhibitors. Approximately 55% of breast cancers may exhibit TGF-β activity via a 153-gene TGF-β response signature.141 Whilst a global reduction in the TGF-β receptor can exert a potent suppressive effect on tumor proliferation, there is an overproduction of this multifunctional cytokine in the setting of breast cancer bone metastases. This then induces osteolysis and angiogenesis via Smad 3, and drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor invasion via multiple signaling pathways (eg, HER2 and ras).142,143 In preclinical studies, TGF-β antagonism is shown to suppress tumor growth and reduce lung/bone metastases by 40% in vivo. The effect appears to be most potent in basal-like (triple-negative) breast cancer cell lines.143 Currently, many TGF-β antagonists have been entered into early phases of clinical development, including antisense oligodeoxynucleotide AP 12009 (Phase I/II for melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and colorectal cancer completed, and Phase III for anaplastic astrocytoma ongoing), monoclonal antibody GC1008 that targets all three isoforms of TGF-β (Phase I for melanoma and renal cell carcinoma completed, and Phase II for mesothelioma ongoing) and the TGF-β type I receptor kinase inhibitor, LY2157299 (Phase I in combination with temozolomide and radiotherapy for glioma to commence, and Phase II in hepatocellular carcinoma to commence).63,143

Src is a prototype of the nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that promote cellular proliferation, differentiation, motility and survival, having mediated signaling via the endothelial growth factor receptor, IGF-1 receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor.144 In breast cancer, high levels of Src are implicated in increased osteoclast activity by forming ruffled borders, growth and survival via endothelial growth factor receptor, HER2, and PI3-kinase/Akt pathways, and hormone resistance.145 Dasatinib is a multitargeted Src inhibitor used in chronic myelogenous leukemia, which also inhibits Bcr-abl, c-kit, platelet-derived growth factor R-beta, and ephA2.144 In vitro, it is shown to cause maximal inhibition on triple-negative breast cancer cell lines, particularly in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy.145 In vivo, dasatinib inhibits osteoclast differentiation and activity, and rapidly lowers calcium levels.145 Two trials researching dasatinib in the setting of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer have now been completed. Several ongoing Phase II trials include one comparing once-daily versus twice-daily dosing, another combining dasatinib and weekly paclitaxel, and a third comparing dasatinib versus zoledronic acid.63 A dual specific Src/abl inhibitor, saracatinib, has also commenced a Phase II trial in breast and prostate cancer with bone metastases, after demonstrating decreased levels of bone resorption markers in serum and urine in a Phase I study, suggesting a potential effect on osteoclasts.63,144

Cathepsin K is a cysteine protease predominantly responsible for osteoclast-mediated degradation of collagen I in the extracellular matrix, indirectly stimulated by RANK-L and TGF-β via NFATc1.138 High expression of cathepsin K is found on immunohistochemistry in primary breast tumor and bone metastases, but not in liver metastases. This is, in turn, associated with higher stage and negative estrogen receptor status, two poor prognostic factors in breast cancer.146 In a Phase II trial of breast cancer patients with bone metastases, odanacatib, a highly selective cathepsin K inhibitor, was shown to suppress urinary N-telopeptide and urinary deoxypyridinoline markers of bone resorption after four weeks of treatment to similar levels when compared with zoledronic acid.147 There are as yet no reports on its effect on skeletal-related events or quality of life.

CXCR4 is the most abundantly expressed chemokine receptor on a breast cancer cell. This “attracts” the cancer cell to the bone, where there is a high level of stromal cell-derived factor-1, the only ligand of CXCR4.20 As mentioned previously, CXCR4 is important in tumor migration, but it also has a positive role in tumor detachment from the primary site, tumor extravasation into secondary sites, and possibly in angiogenesis.148 CXCR4 antagonists, be it small molecules, peptides, antibodies, or small interfering RNAs, consistently reduce bone metastases in all animal models of different cancers.148 CTCE-9908, a peptide analog of stromal cell-derived factor-1 that acts as a competitive antagonist of CXCR4, has been studied in a Phase I/II clinical trial. It showed some preliminary signs of activity, with five patients having stable disease among the 30 patients who received the drug (including eight patients with breast cancer).25 Other options for the development of this drug include combination with chemotherapy or combination with zoledronic acid.138

Many other novel “bone cycle” inhibitors have only entered the early phase of clinical development. It is anticipated that there will be a surge of clinical trial data in the next few years. The significant results in the denosumab trials bear witness to the potential efficacy with these specific targeted therapies, and they are likely to become a crucial part of the armamentarium in the battle against bone metastases in the future.

Predictive biomarkers and bone markers

Biomarkers are a fundamental feature of the strategy of “personalizing medicine”. A biomarker assay with high sensitivity and specificity may potentially help clinicians to screen high-risk patients for bone metastases, to select the right therapy for these patients, and to monitor treatment. To this end, various groups have performed specific (eg, immunohistochemistry, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) or global (eg, proteomic studies, gene microarray) analyses on a large collection of breast cancer tissues and correlated these with clinical outcome in order to discover gene or protein sets that will best predict bone recurrence or skeletal-related events.14,105,151,152 Bohn et al assessed the difference between 64 primary breast cancer and 16 breast cancer bone metastases using tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry, but they were only able to identify HER-2 (18.5% versus 9%, P = 0.016) and tumor size >2 cm (68.75% versus 40.6%, P = 0.042) as predictive markers for bone metastases. There was no significant difference in the protein expression of the trefoil peptide, TFF-1, CXRC4, matrix metalloproteinase-1, parathyroid hormone-related protein, CD44, FGFR3, interleukin-11, and estrogen receptors/progesterone receptors between bone metastases and primary breast cancer.151 Using gene microarray and bioinformatics analysis, Smid et al found that tumors with a luminal subtype gene signature were more likely to develop bone metastases (P = 0.0031).105 Moreover, their group has developed a 31-gene signature that can predict bone metastases with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 50%. This compares favorably with estrogen receptor status (sensitivity 74% and specificity 63%), which is the clinical marker most closely related to bone metastases at this stage.153 Within this gene signature, the key gene sets include trefoil protein-encoding genes (TFF1 and TFF3), genes related to the fibroblast growth factor receptor-MAPK signaling pathway, and cell adhesion.153 Other groups have utilized surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization-assisted or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight for mass protein profiling of serum and plasma, particularly because serum assays are convenient for patients and therefore appealing as a simple diagnostic test. Although multiple protein peaks have been observed in the serum of breast cancer patients (not specifically with bone metastases), the results are hampered by only a small percentage of reported peaks having been structurally identified, and the results being not entirely reproducible with validation studies.154 Thus, the definitive value of proteins identified through proteomic technology is questionable at this stage, and the 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines state that “… there is insufficient evidence to recommend use of proteomic patterns for management of patients with breast cancer”.155

Aside from protein and gene markers, the many clinical trials that have amassed over time have allowed multivariate analysis to detect clinical parameters that may predict skeletal-related events whilst patients are on treatment for bone metastases. For example, using the datasets from a large randomized Phase III trial comparing zoledronic acid and pamidronate, Brown et al have identified multiple baseline clinical parameters that significantly multiply the risk of skeletal-related events whilst on zoledronic acid treatment, including age ≥60 years (HR 1.7), Brief Pain Inventory score >3 units (HR 2), history of skeletal-related events before study entry (HR 1.6), and predominance of osteolytic versus osteoblastic lesions (HR 1.8).156 To summarize, advances in science and translational research have produced a surge in potential biomarkers. Whilst many of these candidate markers still require validation in large clinical studies, it is anticipated that, in the future, there will be more sensitive and specific biomarkers than estrogen receptor positivity alone.