Abstract

Although rare, male breast cancer (MBC) remains a substantial cause for morbidity and mortality in men. Based on age frequency distribution, age-specific incidence rate pattern, and prognostic factor profiles, MBC is considered similar to postmenopausal breast cancer (BC). Compared with female BC (FBC), MBC cases are more often hormonal receptor (estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor [ER/PR]) positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative. Treatment of MBC patients follows the same indications as female postmenopausal with surgery, systemic therapy, and radiotherapy. To date, ER/PR and HER2 status provides baseline predictive information used in selecting optimal adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy and in the selection of therapy for recurrent or metastatic disease. HER2 represents a very interesting molecular target and a number of compounds (trastuzumab [Herceptin®; F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland] and lapatinib [Tykerb®, GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK]) are currently under clinical evaluation. Particularly, trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody which selectively binds the extracellular domain of HER2, has become an important therapeutic agent for women with HER2-positive (HER2+) BC. Currently, data regarding the use of trastuzumab in MBC patients is limited and only few case reports exist. In all cases, MBC patients received trastuzumab concomitantly with other drugs and no severe toxicity above grade 3 was observed. However, MBC patients that would be candidate for trastuzumab therapy (ie, HER2+/ER+ or HER2+/ER− MBCs) represent only a very small percentage of MBC cases. This is noteworthy, when taking into account that trastuzumab is an important and expensive component of systemic BC therapy. Since there is no data supporting the fact that response to therapy is different for men or women, we concluded that systemic therapy in MBC should be considered on the same basis as for FBC. Particularly in male patients, trastuzumab should be considered exclusively for advanced disease or high-risk HER2+ early BCs. On the other hand, lapatinib (Tykerb), a novel oral dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets both HER2 and epidermal growth factor receptor, may represent an interesting and promising therapeutic agent for trastuzumab-resistant MBC patients.

Keywords: target therapy, trastuzumab, lapatinib

Introduction

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare disease compared with female breast cancer (FBC). However, its incidence is increasing. Similar to breast cancer (BC) in women, MBC is likely to be caused by the concurrent effects of different risk factors, including hormonal, environmental, and genetic risk factors. Compared with women, BC in men occurs later in life, is mostly represented by invasive ductal carcinoma with higher stage, lower grade and more likely expresses estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and less likely overexpresses human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). In general, MBC resembles postmenopausal hormone receptor positive FBC.1

Overall, MBCs are diagnosed with a more severe clinical presentation than in women and prognosis in male is worse than in female patients. BC mortality and survival rates have improved significantly over time for both male and female BC. Decline in MBC mortality rates would likely reflect the impact of adjuvant systemic treatments, since men did not receive screening mammography. Indeed, the improvement for male is smaller when compared with female patients, suggesting a delay or nonappropriate utilization of adjuvant therapy. To date, MBC treatment follows the same indications as female postmenopausal BC, with some minor variations.

Since its clinical introduction, trastuzumab (Herceptin®; F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), a monoclonal antibody which selectively binds the extracellular domain of HER2, has become an important therapeutic agent for women with HER2-positive (HER2+) BC and has changed, in particular, clinical management of HER2 overexpressing advanced BC patients. Thus far, only few data have been reported about the role of trastuzumab in MBC patients.

In this review, we described the available information on MBC, with particular regard to epidemiological, genetic, and clinicopathologic aspects, and the current use of trastuzumab in FBC in order to shed some light on the possible use of trastuzumab in male patients with HER2+ BC.

Male breast cancer

Epidemiology

In western countries, MBC makes up less than 1% of all cancers in men and its incidence seems to vary according to different geographical areas and ethnic groups.2–5 The worldwide variation of MBC resembles that of FBC, with higher rates in North America and Europe and lower rates in Asia. A substantial high incidence (from 5% to 15%) is reported in Africa6,7 where the relatively high rates have been attributed to endemic infectious diseases causing liver damage and leading to hyperestrogenisms. Jewish men are the ethnic group with a higher than average incidence (2/3 per 100,000 per year).8

Although rare, MBC appears to be increasing as reported by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and reviewed by the United Kingdom Association of Cancer Registries.1,9 Data from the SEER database indicate that the incidence of MBC has been increasing during the last 30 years, from about 1 per 100,000 to around 1.2 per 100,000. The incidence of MBC increases steadily with age and, differently from the bimodal age frequency distribution seen in women, the age frequency distribution in men is unimodal with peak incidence in the early seventh decade. Age-specific incidence patterns show that the biology of MBC may resemble that of late-onset postmenopausal FBC.10 Furthermore, similar BC incidence trends over time among men and women suggest that there are common BC risk factors that affect both sexes.11

MBCs are diagnosed at a more advanced age and with a more severe clinical presentation than in women, with greater tumor size, and a more frequent lymph nodes involvement.10 The mean age of BC presentation in males is mostly in late 60s, which is about 10 years greater than in female patients. The mortality and survival rates for MBC have improved in the general population over time.11 The overall 5- and 10-year survival rates of MBC patients are around 60% and 40%, respectively. No significant difference in terms of disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS) between female and male BC patients has been observed.11 BC mortality and survival rates have improved significantly over time for both male and female BC. However, the relative improvement was less significant for men compared with women. Decline in FBC mortality rates are attributed to adjuvant systematic therapy and screening mammography. Decline in MBC mortality would likely reflect just the impact of adjuvant systematic treatment since men do not receive screening mammography. Indeed, the improvement for male is smaller when compared with female BC patients, suggesting an underutilization or nonappropriate utilization of adjuvant therapy.

Risk factors

Similar to BC in women, MBC seems to be caused by the concurrent effects of different risk factors including clinical disorders relating to hormonal imbalances, specific occupational/environmental exposures, and genetic risk factors, particularly a positive family history (FH) of BC and mutations in BC predisposing genes, such as BRCA1/2 and possibly others genes.

Hormonal imbalance between an excess of estrogen and a deficiency of testosterone represents one of the major risk factors related to MBC. This imbalance may occur endogenously due to testicular abnormalities, liver disease, obesity, Klinefelter’s syndrome, and gynecomastia. Conditions increasing exposure to estrogen or decreasing exposure to androgen, such as the long-term use of antiandrogens and estrogens in the treatment of prostate cancer, the exogenous administration of estrogen to trans-sexuals or abuse of steroids for physical performances have also been implicated as causative factors for MBC.12–14

With regard to occupation and environmental risk factors, occupational exposure to heat and electromagnetic radiation seems to be associated with MBC risk. As in women, ionizing radiations have been considered as possible causal cofactors in the etiology of MBC.15 Overall, environmental factors, particularly occupational carcinogen exposure, might contribute to MBC risk by interacting with genetic factors. Indeed, we observed a strong association between a specific occupation (truck driving) and BC risk in male carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations.16

Similar to FBC, a positive FH of BC is associated with increased risk of MBC. About 20% of all MBC patients have a history of BC in first-degree female relatives. A positive FH of either female or male BC among first-degree relatives confers a 2- to 3-fold increase in MBC risk.17–23 The risk raises with increasing number of first-degree relatives affected and with early onset in affected relatives. A personal history of a second primary tumor is reported in more than 11% of MBC patients.24 Men diagnosed with a first primary BC have a 16% increased risk of developing a second primary cancer in comparison with the general male population.24 Data from the SEER program from the NCI show that a history of MBC is associated with a 30-fold increased risk of BC on the contralateral side, which is much higher than the 2- to 4-fold increase observed in women.25,26

The major genetic risk factor for MBC predisposition is represented by germ-line mutations in BRCA2 and with lower frequency, BRCA1 genes. The frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations is different in ethnically diverse population and clinically based MBC series, ranging from 4% to 40% for BRCA2 and up to 10% for BRCA1, resulting higher in the presence of founder effects.27,28BRCA1 and BRCA2 founder mutations have been identified in specific countries or ethnic groups, particularly in genetically isolated populations such as the Icelanders and Ashkenazi Jews. However, even in heterogeneous countries, such as Italy, there is evidence of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in regions that show microhomogeneity.29–35

Overall, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are more prevalent in men with a positive first-degree FH compared with those without.17,36,37 Although BRCA2 mutations are currently considered as the major genetic risk factor for MBC, there is no evidence for a correlation between the location of the mutation within the gene and MBC risk. Notably, the median age at BC diagnosis among BRCA2 mutation carriers is earlier (median, 58.8 years) than that of negative cases (median, 67.9 years).17

Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment

The predominant histological type of BC in men is invasive ductal carcinoma, which represents about 90% of all male breast tumors.38 Much rarer tumor types include invasive papillary and medullary carcinoma and Paget disease.32,39,40 Since the male breast lacks terminal lobules, unless it is exposed to high doses of endogenous and/or exogenous estrogens, the lobular histotype accounts only for about 2% of invasive cancers.27,38 The lobular histotype has been reported in association with Klinefelter’s syndrome and rarely, in genotypically normal men with no previous history of estrogen exposure or gynecomastia.41 Ductal carcinomas in situ are rare and comprise about 10% of BC in men, whereas lobular carcinoma in situ has only been reported in association with invasive lobular carcinoma.38,42

MBCs express high levels of hormone receptors. Compared with FBC, tumors in MBC are more likely to be ER (80%–90% vs 75%) and PR (73%–81% vs 65.9%) positive. The proportion of hormone-receptor-expressing tumors increases with age, as occurs in postmenopausal women.38 The expression of androgen receptors ranges from 39% to 95% according to various reports.43–45

Studies on HER2 expression in MBC are limited and with conflicting results, most likely due to different scoring systems and cut off values used. However, recent studies, performed by using both immunohistochemical (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses, indicate that about 15% of MBCs showed HER2 overexpression.46,47 Overall, overexpression of HER2 is less likely to be present in MBC than in FBC.48,49 Overexpression of HER2 is a well-known prognostic factor associated with poor survival in women with BC. However, data regarding the association between HER2 overexpression and survival are still limited and contrasting in MBC.

Compared with women, BCs in men occur later in life, are mostly invasive ductal carcinomas with higher stage, lower grade and are more often ER+ and HER2 negative (HER2–) tumors. In general, prognosis in male is worse than in female patients, probably because of advanced stage at diagnosis together with higher age of male patients, often leading to the coexistence of serious comorbidities.

Recently, IHC markers have been used to classify BC in five molecular classes: luminal A (ER+ and/or PR+, HER2–), luminal B (ER+ and/or PR+, HER2+), basal-like (ER–, HER2–, CK5/6+, or HER1+), HER2+/ER–, and unclassified (negative for all markers).50 The role and the relevance of these five BC subclasses in MBC patients are still largely unknown. A recent study, based on 42 MBC cases, showed that the luminal A subtype was the most common profile (83%) in MBC, whereas basal-like and HER2+/ER–BCs were not identified.46 Notably, the HER2+/ER–subtype associates with a worse prognosis in FBC. This may raise questions on the correlation in prognosis, as well as in response to therapy, of BC in males and females, since frequency of BC subtypes between FBC and MBC seems to be different. The luminal B subtype was observed in 17% of MBCs and tended to have high nuclear grade and more frequent epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression. Furthermore, BC patients with luminal B subtype showed nodal involvement more frequently.

Overall, due to age frequency distribution, age-specific incidence rate pattern, and prognostic factor profiles, MBC is considered similar to postmenopausal FBC51 and with some minor variations, MBC treatment follows the same indications as female postmenopausal BC.

To date, because there have been few clinical trials on treatment of MBC, most oncologists base their treatment recommendations on their personal experience with the disease and on the results of studies of BC in women. Particularly, tumor response for metastatic MBC has shown a similar behavior and similar predictive/prognostic factors as for postmenopausal FBC.27,52 As in females, BC in males can spread to the liver, lungs, and bones.

In men with hormone-dependent BC, tamoxifen and aromatese Inhibitors have been used and can increase survival to the same extent as in women with BC. Responses are generally similar to those seen in women with BC. Particularly, tamoxifen (standard treatment in ER+ disease) has shown its beneficial effect in visceral dominant, bone dominant, and soft tissue dominant metastasis and the response depends on ER% positivity.53,54

Systemic chemotherapy can be used in failed hormonal therapy or in ER–patients. In this setting, a study reported response rates of 67% for 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide; 55% for doxorubicin and vincristine; 53% for cyclophosphamide, 33% for cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; and 13% for 5-fluorouracil.55

HER2

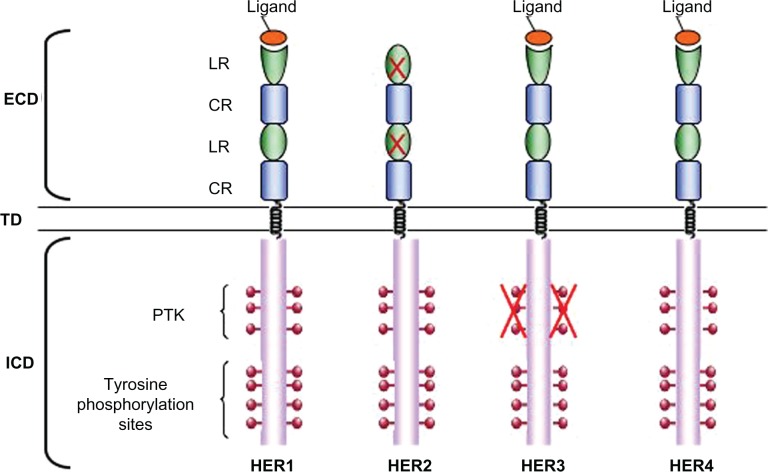

HER2 is a member of the epidermal growth factor family (ErbB family) that consists of four transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors: ErbB1 (EGFR/HER1), ErbB2 (HER2), ErbB3 (HER3), and ErbB4 (HER4). These transmembrane receptors are characterized by an extracellular ligand-binding domain, an α-helical transmembrane domain, and an intracellular tyrosine kinase regulatory domain that contains conserved sequences that are subject to autophosphorylation and phosphorylation by heterologous protein kinases (Figure 1).56,57

Figure 1.

HER family receptors. Epidermal growth factor family (ErbB) receptors are characterized by an extracellular domain (ECD), consisting of two Leu-rich ligand-binding subdomains (LR) and two Cys-rich subdomains (CR), a α-helical transmembrane domain and a intracellular domain (ICD), comprising the catalytic protein tyrosine kinase subdomain (PTK) and multiple regulatory tyrosine residues which become phosphorylated on receptor activation. The crosses on the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) ligand-binding domains indicate their lack of functionality and on HER3 protein tyrosine kinase subdomain indicate that it is catalytically inactive.

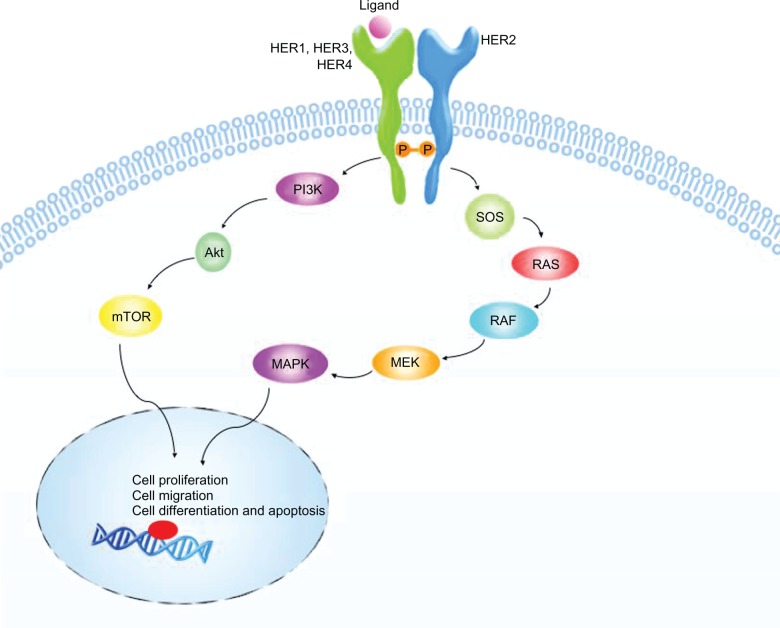

ErbB receptors normally exist as inactive monomers, ligand binding to the extracellular domain stabilizes the formation of active dimers (Figure 2). Dimerization can occur between two different ErbB receptors or between two domains of the same receptor and results in kinase domain activation, leading to transphosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the domains. Phosphorylation on tyrosine residues creates binding sites for adaptor or effector proteins containing Src-homology (SH2) and phosphotyrosine-binding domains.56,58 The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are two important signaling pathways activated by ErbB receptors (Figure 2). These pathways activate gene transcription resulting in proteins involved in cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis.58

Figure 2.

HER2 pathway. Ligand binding to the extracellular domain of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1/3/4) stabilizes the formation of active HER2 heterodimers. Transphosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the intracellular domains results in kinase domains activation. Phosphorylation creates binding sites for adaptor or effector proteins (SOS and PI3K) that activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathways. These pathways result downstream in transcription of genes driving cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis.

HER2 has an active tyrosine kinase domain but it has no known extracellular ligand. Rather, it is a coreceptor that heterodimerizes with other activated ErbB receptor. HER2 is the preferred heterodimerization partner of all other ErbB receptors, increasing their ligand binding affinity.59,60 Heterodimers containing HER2 are more stable than other heteromeric ErbB combinations, and consequently signaling from HER2 heterodimers is probably more powerful and enduring than from other ErbB combinations.61

Several types of human cancer, including BC, are associated with deregulation of ErbB signaling due to gene amplification and/or protein overexpression. Amplification of HER2 gene produces protein levels up to 100 times greater than the normal one and the increased overexpression of HER2 protein may lead to increased homodimers and heterodimers of HER2, causing constitutive activation.62 HER2 amplification and overexpression are reported in more than 25% of FBC.62–64 HER2 gene amplification and protein overexpression correlate with breast tumor size, high-tumor grade, lymph nodes involvement, high cell proliferation rate, aneuploidy, and lack of ER and PR.57 Furthermore, an inverse association between HER2 expression and long-term survival has been reported in women affected by BC.65

Somatic mutations of HER2 gene have been found in BC with an incidence of about 4%. The great majority of HER2 mutations occur in exons 18–23, particularly exons 19 and 22, encoding the kinase domain.63 Interestingly, a specific splicing variant of HER2 (ΔHER2), which causes loss of exon 16 encoding the extracellular domain, has been identified in 9% of BC overexpressing HER2 protein.66,67

HER2 is a well-known prognostic factor associated with poor survival in FBC; by contrast, the association between HER2 overexpression and survival is still debated in MBC.49,68,69 However, in MBC HER2 overexpression has been associated with specific phenotypic characteristics indicative of aggressive behavior, including high-tumor grade (G2, G3) and stages 3 and 4.39,40,69–71

To date, HER2 BC status provides baseline predictive information used in selecting optimal adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy and in the selection of therapy for recurrent or metastatic disease.

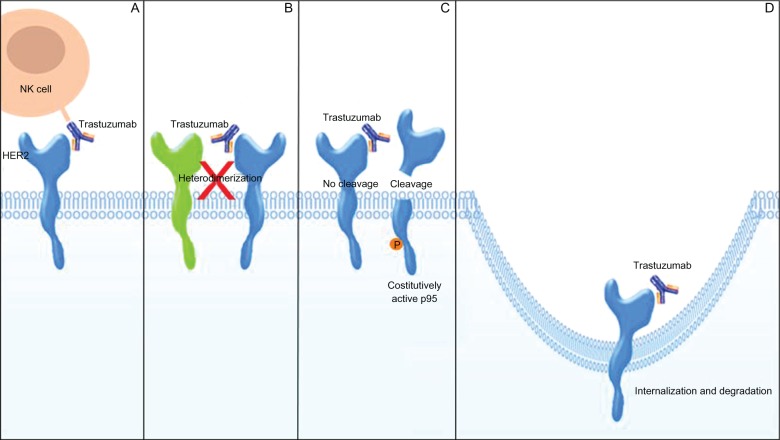

Targeting HER2: trastuzumab

Trastuzumab (Herceptin) is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) kappa monoclonal antibody, which consists of two antigen-specific sites that selectively bind, with high affinity, the extracellular domain of the human HER2 receptor.72 Trastuzumab, developed by the Genentech Corporation (South San Francisco, CA, USA), is produced by recombinant DNA technology in a mammalian cell (Chinese hamster ovary) culture.73,74 It inhibits the proliferation of BC cells that overexpress HER2 protein and mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity on HER2 overexpressing cells.72 There are several possible mechanisms, not completely understood, by which trastuzumab may act in decreasing HER2 signaling (Figure 3). Both preclinical and pilot clinical studies indicate a cytotoxic role for trastuzumab. The IgG1 Fc structure of the antibody may recruit Fc-competent immune effector cells, in particular natural killer cells, leading to the activation of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. This event causes the lysis of cancer cells bound to trastuzumab.75–77 Trastuzumab may reduce HER2 signaling by physically impeding either HER2 homodimerization or heterodimerization with other HER family partners and by inhibiting HER2 proteolytic cleavage that occurs when HER2 is overexpressed, thus preventing the formation of a truncated membrane-bound phosphorylated fragment (p95) which can constitutively activate signal-transduction pathways.78,79 Furthermore, trastuzumab may reduce the signaling from PI3K-Akt and MAPK pathways by the internalization and degradation of HER2 receptor.80 Trastuzumab specifically inhibits cell proliferation by reducing phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) tyrosine phosphorylation and increasing PTEN membrane localization and phosphatase activity and by inducing cell cycle arrest, during the G1 phase, by the accumulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27.81,82 Trastuzumab can also affect angiogenesis by down-regulating specific proangiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor α (TGFα), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and angiopoietin 1, and by upregulating antiangiogenic factors as thrombospondin 1.83

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of action of trastuzumab. A) Trastuzumab may cause immune activation by recruiting natural killer (NK) cells, leading to cancer cells lysis. B) Trastuzumab may physically block either human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) homodimerization or heterodimerization with other HER family partners. C) Trastuzumab may inhibit the shedding of HER2 extracellular domain, preventing the formation of p95. D) Trastuzumab may reduce the signaling from downstream pathways by the internalization and degradation of HER2.

The variety of mechanisms in which trastuzumab is involved may give rise to several mechanisms of resistance developed early or during treatment in HER2+ BCs. First, HER2 heterodimerization with other HER receptors can result in an incomplete inhibition and in an increased signaling. On the other hand, an excess of ligands of HER1, HER3, and HER4, including TGFα, can interfere with trastuzumab and lead to cell growth.84 Mutations in HER2 or in HER2 targets, such as PI3K, might also be involved in trastuzumab resistance. Mutations in exon 21 of HER2 seem to play a role in the development of therapeutic resistance to trastuzumab in metastatic BC.85 Mutated PI3K produces a complex disruption that does not inhibit Akt, thus explaining why trastuzumab may be ineffective in some tumors.86 In PTEN-deficient breast tumors, Akt remains constitutively active and efficacy of trastuzumab is impaired.87 Trastuzumab binds an epitope on HER2, which can be masked by MUC4, a membrane associated glycoprotein. Studies on trastuzumab-resistant cell line demonstrated that levels of MUC4 were inversely correlated with the trastuzumab binding capacity of single cells.88 Furthermore, Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) expression has been associated with an early progression of HER2+ BC and with a lower trastuzumab response rate compared with tumors without expression of IGF-1R.89 Preclinical studies showed that the presence of HER2/IGF1-R heterodimers makes trastuzumab unable to bind to HER2 and to block cell proliferation.90

Trastuzumab and clinical relevance

Since its clinical introduction, trastuzumab has become an important therapeutic agent for patients with HER2+ BC. In a prospective trial, woman with metastatic disease was randomized to receive either chemotherapy alone (doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide [AC] or paclitaxel [P]) or the same chemotherapy and trastuzumab. Patients treated with chemotherapy plus Herceptin had an OS advantage as compared with those receiving chemotherapy alone (25.1 months vs 20.3 months, P = 0.05).

Herceptin received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 1998 for use in women with HER2+ metastatic BC. In this setting, actually, it is indicated for treatment of patients both as a first-line therapy, in combination with chemotherapy (ie, paclitaxel), and as a single agent in second/third-line therapy.91

Recently, four large studies (HERA, BCIRG-006, NSABP B-31, and NCCTG N9831) have consistently demonstrated that Herceptin prolongs survival in woman with HER2 positive early BC.92–94

To date, Herceptin is the only targeted biologic agent approved for treatment of HER2+ BC in the adjuvant settings. Particularly, trastuzumab is used as adjuvant therapy for HER2+ (HER2 gene amplification by a FISH method or scored as 3+ by an IHC method) cancers to reduce the risk of recurrence when the tumor measures larger than 1 cm across or when the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

Trastuzumab in advanced breast cancer patients

Trastuzumab was able to change the clinical management of HER2 overexpressing metastatic BC. Both trials with trastuzumab alone or in combination with taxanes induced clinical benefit. To date, the gold standard for first-line treatment of HER2+ metastatic BC is represented by trastuzumab and chemotherapy (i.e. taxane combination).91–94 This statement is based on the evidences deriving from the pivotal randomized combination trials of trastuzumab (H0648g and M77001), which demonstrated a superior clinical benefit when trastuzumab plus a taxane is confronted with a taxane alone.

The H0648g trial enrolled 469 HER2+ metastatic BC women unpretreated for advanced disease. All clinical end points achieved improvement from the combination of trastuzumab with paclitaxel or with an anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide over paclitaxel or an anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide alone.93 Of patients receiving trastuzumab plus an anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide, 28% experienced a cardiac event, compared with only 9.6% receiving an anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide alone. Of patients receiving trastuzumab plus paclitaxel, 13% experienced a cardiac event, compared with 1% receiving paclitaxel alone. For this reason, the combination of trastuzumab with an anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide is not currently indicated for clinical use.95 If we only consider the trastuzumab plus paclitaxel combination, a higher objective response rate (49% vs 17%), longer time to progression (TTP), and response duration (6.9 months vs 3.0 months and 10.5 months vs 4.5 months) were observed.

In women showing HER2 3+ IHC expression, a median survival time of 25 months was reached with trastuzumab vs 18 months without trastuzumab.96 Outcomes were also improved by the addition of trastuzumab to paclitaxel in IHC HER2 3+ patients relative to the overall patient population (IHC 2+ and 3+).

The M77001 trial investigated, in the same setting of patients, the combination of weekly trastuzumab plus weekly or 3-weekly docetaxel. The median OS time was significantly higher with trastuzumab plus docetaxel than with docetaxel alone (31.2 months vs 22.7 months), even if 57% of patients documented crossover. All clinical outcomes investigated, including the median duration of response (11.4 months vs 5.1 months) and median time to disease progression (TTP; 10.6 months vs 5.7 months), were superior for trastuzumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone.92

Because other trastuzumab-containing regimens may be required for patients who are not candidates for taxane-based treatments, further combinations have been studied. Combinations of trastuzumab standard schedule with agents such as vinorelbine, gemcitabine, and capecitabine achieved interesting results.97

Currently, only few case reports exist about the use of trastuzumab in MBC patients, and in all cases, patients received Herceptin concomitantly with other drugs (chemotherapy or hormonal agents).98

A first case report, published in 2001, described a 52-year-old man with ER+, PR+, and HER2+ locally recurrent BC treated with radical mastectomy after three preoperative courses of epirubicin and cyclophosphamide. After surgery, he received radiotherapy and sequential chemotherapy with epirubicin and cyclophosphamide, finally the patient received tamoxifene. Experiencing progression for lung and bone metastases, the second-line chemotherapy included paclitaxel and trastuzumab, achieving a complete response of the lung metastases. A partial clinical response and good clinical benefit were obtained 9 months after the initiation of trastuzumab therapy.

Recently, Carmona-Bayonas99 reported a case of a metastatic MBC who achieved a complete response lasting >6 months with trastuzumab and anastrazole. The case was a 40-year-old man with ER+ and HER2+ BC treated with modified radical mastectomy. When he developed bone metas tases, received radiotherapy and sequential chemotherapy with epirubicin and cyclophosphamide, experiencing progression for lung and liver metastases after five courses. Second-line chemotherapy included docetaxel and trastuzumab, achieving a complete response of the lung metastases, and partial response of the liver lesions. Then, anastrozole and trastuzumab maintenance therapy was begun and continued until progression. A complete response lasting 11 months was obtained with an excellent quality of life. At further progression time, he received fulvestrant and trastuzumab for 4 months with stable disease.

Another recent study of Hayashi et al100 reported a case of advanced HER2+ MBC with lung metastases, which showed a good response to concomitant treatment of weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel. The case was a 78-year-old man with ER–, PR–, and HER2+ BC. The patient was treated with weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel. He experienced a partial response and trastuzumab was continued as maintenance therapy. His quality of life was improved and no severe adverse events above grade 3 were observed.100

Overall, in these case reports, no severe toxicity above grade 3 was observed.

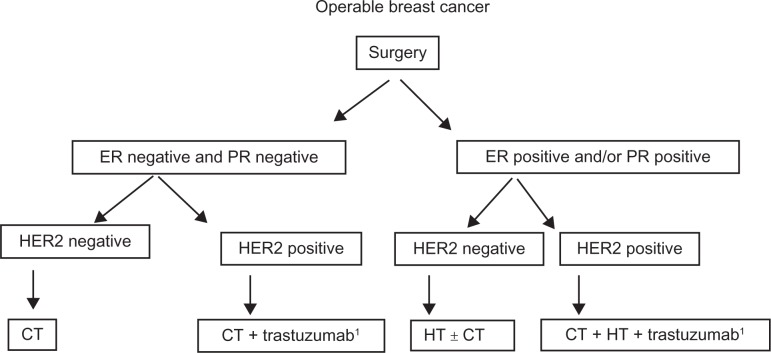

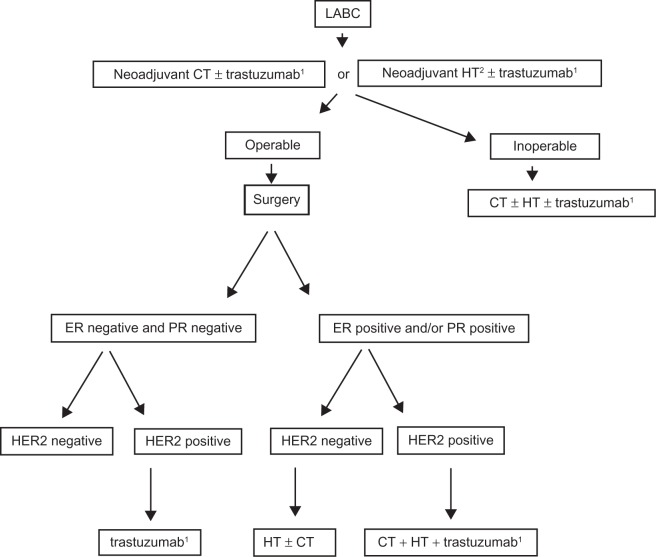

According to NCI and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines in MBC systemic therapy should be considered on the same basis as for a woman with BC since there is no data supporting the fact that response to therapy is different for men or women. Particularly, adjuvant trastuzumab should be considered exclusively for high-risk HER2+ MBC (Figures 4 and 5).101,102 However, patient preference is a major component of the decision-making process, especially in situations in which survival data are less among the available treatment options.

Figure 4.

Proposed algorithm for the treatment of operable male breast cancer.

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; CT, chemotherapy; HT, hormonal therapy.

Note: 1T ≥ 1 cm/N+; Levels of evidence, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of trastuzumab in early male breast cancer.

Figure 5.

Proposed algorithm for the treatment of locally advanced (inoperable) male breast cancer.

Abbreviations: LABC, locally advanced breast cancer; CT, chemotherapy; HT, hormonal therapy; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Note: 1HER2-positive tumors; 2ER positive and/or PR positive; Levels of evidence, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of trastuzumab or neoadjuvant CT in male breast cancer setting.

Trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy in early breast cancer patients

The clinical efficacy of trastuzumab in early BC was evaluated in four large randomized clinical trials and one smaller randomized Finnish trial: the Breast International Group Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA), Breast Cancer International Research Group (BCIRG)-006, the NSABP B-31, Intergroup N9831, and Finnish FinHer trial.103–105 All these trials included HER2+ invasive BC patients radically resected by lumpectomy or mastectomy. Both node positive or high-risk nodenegative patients were enrolled. All patients were to receive adjuvant chemotherapy and appropriate radiotherapy and hormonal therapy.

The HERA trial compared every-3-weeks trastuzumab for 1 year or 2 years with no trastuzumab in patients with HER2+ early BC who were radically resected and received at least four cycles of approved regimens of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. The patients treated with 1 year of trastuzumab vs observation showed a statistically significant 36% reduction in disease recurrence (HR = 0.64; 3-year DFS of 81% vs 74%). OS was also significantly improved by 1-year trastuzumab (HR = 0.66; 92% vs 90% in the trastuzumab and non-trastuzumab arms).104

The FinHer trial randomized patients to receive three cycles of docetaxel or vinorelbine followed by three cycles of fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide. The study was designed to compare docetaxel and vinorelbine. However, the HER2+ BC patients were further randomized to receive or not receive 9 weeks of trastuzumab during the delivery of docetaxel or vinorelbine. Significantly improved DFS was found among those who received trastuzumab (89% vs 78%; P = 0.01) with a trend toward better OS (96% vs 90%; P = 0.07).103

Updated results from these trials were presented at st Gallen consensus conference 2009 and continued to demonstrate the relevant role of trastuzumab-based treatment for patients with HER2+ disease.

The BCIRG-006 trial evaluated three regimens as adjuvant systemic therapy after radical surgery. Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab plus docetaxel chemotherapy (AC-TH), docetaxel and carboplatin plus trastuzumab (TCH), and AC followed by docetaxel alone (AC-T) as the control arm. An interim analysis of one-third of the required number of events showed that a significant improvement of DFS in both trastuzumab arms as compared with the control arm (HR = 0.49 and 0.61 for AC-TH and TCH, respectively). Results from the third analysis of BCIRG 006 showed that patients with HER2+ breast tumors assigned to trastuzumab had a DFS as good as, or better than, that of patients assigned to anthracycline-based chemotherapy. There were 214 DFS events in the TCH group (HR = 0.75; 95% CI: 0.63–0.90) vs 257 in the ACT group and 185 in the AC-TH group (HR = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.58–0.78). There were 113 deaths in the TCH group (HR = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.60–0.99) vs 141 in the ACT group and 94 in the AC-TH group (HR = 0.63; 95% CI: 0.48–0.81). However, no significant advantage was reported for DFS in the AC-TH arm compared with TCH; finally, 21 congestive heart failures (CHF) were reported in the AC-TH group vs four in the TCH group.

The NSABP B-31 trial compared four cycles of AC followed by four cycles of every-3-week paclitaxel (P; ACP) with the same regimen plus 1 year of weekly trastuzumab (H) beginning with the first cycle of P.105

The N9831 trial compared three arms: four cycles of AC followed by 12-weekly doses of paclitaxel with the same regimen plus 1 year of H beginning after P in the second arm and beginning with the first P cycle in the third arm. In an intent-to treat analysis, there was a highly significant 52% reduction in the risk of disease recurrence with sequential trastuzumab (3-year DFS, 87% vs 75%; HR = 0.48), and a 33% reduction in the risk of death (3-year OS, 94.3% vs 91.7%; HR = 0.67).105

Overall, data regarding the indications for trastuzumab in male patients is limited. In particular, the activity of trastuzumab in HER2 overexpressing metastatic MBC remains to be established, and in adjuvant setting, there is no data about the efficacy or safety of this drug.

Tolerability profile of trastuzumab

Herceptin is given as an injection into a vein (IV), usually once a week (loading dose, 4 mg/kg as a 90 minutes of infusion and maintenance dose, 4 mg/kg as a 30 minutes of infusion) or at a larger dosage once every 3 weeks (loading dose, 8 mg/kg as a 90 minutes of infusion and maintenance dose, 6 mg/kg as a 30 minutes of infusion). Trastuzumab follows a nonlinear but dose-dependent pharmacokinetic profile. Clearance decreases and T1/2 (28.5 days) increases with increasing dose.

The metabolism of trastuzumab is not fully understood, but it appears that the elimination of drug would involve clearance of IgG through the reticuloendothelial system. Trastuzumab was generally well tolerated in clinical trial for adjuvant treatment.105,106 Compared with other anticancer drugs, the side effects of trastuzumab are relatively mild. They may include fever and chills, weakness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and headache.107,108 During the first infusion with trastuzumab, fever and/or chills, up to 40%, are observed in patients. These side effects are less common after the next dose.

A more serious potential side effect is heart damage leading to CHF. Cardiotoxicity of any grade occurs in 4% (3% class 3/4) of patients who receive trastuzumab as a single agent. Symptoms of severe cardiotoxicity may include dyspnea, increased cough, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and peripheral edema. The risk of heart problems is higher when trastuzumab is given with certain chemotherapy drugs such as doxorubicin or epirubicin. Because of this increased frequency, combined therapy with an anthracycline is not recommended. The risk of cardiac dysfunction associated with trastuzumab therapy may be increased in older patients, patients with preexisting cardiac disease, and patients who have had prior cardiotoxic therapy or radiation therapy to the chest area. To date, cardiac assessment is mandatory at baseline and 3-monthly throughout treatment. The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence advises against the administration of trastuzumab to women with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≤55%, a history of documented CHF, high-risk uncontrolled arrhythmias, angina pectoris requiring medication, clinically significant valvular disease, evidence of transmural infarction on ECG or poorly controlled hypertension. Cardiotoxicity associated with trastuzumab typically responds to medical therapy (diuretic, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or digoxin) but may be severe and lead to cardiac failure with mural thrombi and stroke.109

The HERA trial highlighted the adverse effects of every-3-weeks trastuzumab for 1 year after adjuvant chemotherapy observed in ≥5% of patients. These effects included arthralgia (8%), back pain (5%), nasopharyngitis (8%), fatigue (8%), peripheral edema (5%), pyrexia (6%), chills (5%), diarrhea (7%), nausea (6%), headache (10%), and cough (5%).105 In the same trials, trastuzumab group patients experienced higher frequency of severe CHF, symptomatic CHF, and confirmed significant LVEF decline than in the observation group. Four percent of trastuzumab-treated patients needed to discontinue treatment because of cardiac disorders. Recovery of cardiac function was obtained within 6 months in most patients.110

A higher incidence of cardiac toxicity in the trastuzumab arm was also reported in the NSABP B-31 trial. At 3-year follow-up, the relative risk of a cardiac event in trastuzumab-treated patients was 5.9 (P < 0.0001). CHF was more frequent in older patients and those with a borderline LVEF following anthracycline therapy.111

The N9831 trial showed that cumulative incidences at 3 years of cardiac events (CHF or cardiac death) in the groups receiving trastuzumab with paclitaxel (n = 570), trastuzumab after paclitaxel (n = 710) or chemotherapy alone were 3.3% and 2.8% vs 0.3%, respectively. This study also found an increased risk of a cardiac event in patients with older age (≥60 years), the prior or current use of antihypertensive agents, and an LVEF of <55% at baseline.112

Emerging options in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer patients

HER2 represents a very interesting molecular target and a number of other compounds have been developed and are currently evaluated in clinical trials. Lapatinib (Tykerb®) is a novel oral dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets EGFR and HER2, both overexpressed in a considerable percentage of BCs. Results from recent studies in female metastatic BC showed that the combination of lapatinib plus letrozole as a first-line treatment regimen provided a significant improvement in delaying disease progression when compared with treatment with letrozole alone. Moreover, lapatinib therapy was shown to prolong the TTP and increase the rate of response to capecitabine in patients who had received anthracycline-based and taxane-based chemotherapy, and whose tumors had progressed on trastuzumab. However, to date, there is no data on the role of lapatinib in MBC setting. Taking into account the synergistic effect of lapatinib and hormone therapy and considering that EGFR may play a relevant role in MBC, this drug might represent an interesting and promising therapeutic agent for trastuzumab-resistant MBC patients.113 Pertuzumab is another recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that is specifically designed as a HER2 dimerization inhibitor. Since Pertuzumab and trastuzumab bind different subdomains of the HER2 extracellular domain, combinational therapy of these two antibodies may be proposed since they act synergistically in inhibiting BC cell growth.114

Conclusions

Monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab have become important yet expensive components of systemic BC therapy. Preoperative systemic therapy is commonly used in women with locally advanced BC. In particular, in HER2+ female locally advanced BC, trastuzumab should be offered as neoadjuvant treatment alongside chemotherapy and after surgery, continued as adjuvant treatment.

So far, there is no data regarding the neoadjuvant trastuzumab-based treatment in MBC setting. However, in neoadjuvant or metastatic setting, trastuzumab-based therapy can be considered on the same basis as for a woman with BC since there is no data supporting the fact that response to therapy is different for men or women.

With regard to adjuvant setting, to date, there is no established standard therapy for HER2+ MBC patients. Given the high cost and safety data, adjuvant trastuzumab should be considered investigational and exclusively for high-risk HER2+ MBC cases. In addition, particular attention should be used in older patients with preexisting cardiac disease and patients who have had prior cardiotoxic therapy or radiation therapy to the chest area.

From a practical point of view, considering the finite resources that most health systems face, it should be considered that trastuzumab-containing regimens are expensive. In this context, it is noteworthy that MBC represents a very rare disease taking into account that MBC patients candidate for trastuzumab therapy (ie, HER2+/ER+ or HER2+/ER–MBCs) would represent only a very small percentage of MBC cases (0.0015% of all BC). Thus, similar to other rare diseases that have specific reimbursement policies providing full medicine refund, trastuzumab can be considered an “orphan drug” for the treatment of HER2+ MBC.

Acknowledgments

Dr Ottini is supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC-IG 8713). Authors wish to thank Dr Mario Falchetti for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Korde LA, Zujewski JA, Kamin L, et al. Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: summary and research recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2114–2122. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer incidence in five continents. IARC Sci Publ. 1976:1–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss JR, Moysich KB, Swede H. Epidemiology of male breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stang A, Thomssen C. Decline in breast cancer incidence in the United States: what about male breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:595–596. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9882-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contractor KB, Kaur K, Rodrigues GS, Kulkarni DM, Singhal H. Male breast cancer: is the scenario changing. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhagwandeen SB. Carcinoma of the male breast in Zambia. East Afr Med J. 1972;49:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ojara EA. Carcinoma of the male breast in Mulago Hospital, Kampala. East Afr Med J. 1978;55:489–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mabuchi K, Bross DS, Kessler II. Risk factors for male breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;74:371–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speirs V, Shaaban AM. The rising incidence of male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:429–430. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0053-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN. Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:678–687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Tse J, Rosenberg PS. Male breast cancer: a population-based comparison with female breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:232–239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coard K, McCartney T. Bilateral synchronous carcinoma of the male breast in a patient receiving estrogen therapy for carcinoma of the prostate: cause or coincidence? South Med J. 2004;97:308–310. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000050686.54786.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganly I, Taylor EW. Breast cancer in a trans-sexual man receiving hormone replacement therapy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:341. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karamanakos P, Mitsiades CS, Lembessis P, Kontos M, Trafalis D, Koutsilieris M. Male breast adenocarcinoma in a prostate cancer patient following prolonged anti-androgen monotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1077–1081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DB, Rosenblatt K, Jimenez LM, et al. Ionizing radiation and breast cancer in men (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01830721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palli D, Masala G, Mariani-Costantini R, et al. A gene-environment interaction between occupation and BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in male breast cancer? Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2474–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basham VM, Lipscombe JM, Ward JM, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based study of male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4:R2. doi: 10.1186/bcr419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casagrande JT, Hanisch R, Pike MC, Ross RK, Brown JB, Henderson BE. A case-control study of male breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1326–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewertz M, Holmberg L, Tretli S, Pedersen BV, Kristensen A. Risk factors for male breast cancer – a case-control study from Scandinavia. Acta Oncol. 2001;40:467–471. doi: 10.1080/028418601750288181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson KC, Pan S, Mao Y. Risk factors for male breast cancer in Canada, 1994–1998. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:253–263. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenfant-Pejovic MH, Mlika-Cabanne N, Bouchardy C, Auquier A. Risk factors for male breast cancer: a Franco-Swiss case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:661–665. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palli D, Falchetti M, Masala G, et al. Association between the BRCA2 N372H variant and male breast cancer risk: a population-based case-control study in Tuscany, Central Italy. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenblatt KA, Thomas DB, McTiernan A, et al. Breast cancer in men: aspects of familial aggregation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:849–854. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.12.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satram-Hoang S, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Risk of second primary cancer in men with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R10. doi: 10.1186/bcr1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auvinen A, Curtis RE, Ron E. Risk of subsequent cancer following breast cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1330–1332. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.17.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broet P, de la Rochefordiere A, Scholl SM, et al. Contralateral breast cancer: annual incidence and risk parameters. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1578–1583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giordano SH. A review of the diagnosis and management of male breast cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10:471–479. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-7-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liede A, Narod SA. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in Asia: genetic epidemiology of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:413–424. doi: 10.1002/humu.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baudi F, Quaresima B, Grandinetti C, et al. Evidence of a founder mutation of BRCA1 in a highly homogeneous population from southern Italy with breast/ovarian cancer. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:163–164. doi: 10.1002/humu.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferla R, Calo V, Cascio S, et al. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Suppl 6):vi93–vi98. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malacrida S, Agata S, Callegaro M, et al. BRCA1 p.Val1688del is a deleterious mutation that recurs in breast and ovarian cancer families from Northeast Italy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:26–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottini L, Rizzolo P, Zanna I, et al. BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status and clinical-pathologic features of 108 male breast cancer cases from Tuscany: a population-based study in central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:577–586. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0194-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papi L, Putignano AL, Congregati C, et al. Founder mutations account for the majority of BRCA1-attributable hereditary breast/ovarian cancer cases in a population from Tuscany, Central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:497–504. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisano M, Cossu A, Persico I, et al. Identification of a founder BRCA2 mutation in Sardinia. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:553–559. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo A, Calo V, Bruno L, et al. Is BRCA1-5083del19, identified in breast cancer patients of Sicilian origin, a Calabrian founder mutation? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:67–70. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9906-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans DG, Bulman M, Young K, et al. BRCA1/2 mutation analysis in male breast cancer families from North West England. Fam Cancer. 2008;7:113–117. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miolo G, Puppa LD, Santarosa M, et al. Phenotypic features and genetic characterization of male breast cancer families: identification of two recurrent BRCA2 mutations in north-east of Italy. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN. Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer. 2004;101:51–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nahleh ZA, Srikantiah R, Safa M, Jazieh AR, Muhleman A, Komrokji R. Male breast cancer in the veterans affairs population: a comparative analysis. Cancer. 2007;109:1471–1477. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ottini L, Palli D, Rizzo S, Federico M, Bazan V, Russo A. Male breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez AG, Villanueva AG, Redondo C. Lobular carcinoma of the breast in a patient with Klinefelter’s syndrome. A case with bilateral, synchronous, histologically different breast tumors. Cancer. 1986;57:1181–1183. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860315)57:6<1181::aid-cncr2820570619>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stalsberg H, Thomas DB, Rosenblatt KA, et al. Histologic types and hormone receptors in breast cancer in men: a population-based study in 282 United States men. Cancer Causes Control. 1993;4:143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00053155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet. 2006;367:595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meijer-van Gelder ME, Look MP, Bolt-de Vries J, Peters HA, Klijn JG, Foekens JA. Clinical relevance of biologic factors in male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;68:249–260. doi: 10.1023/a:1012221921416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munoz de Toro MM, Maffini MV, Kass L, Luque EH. Proliferative activity and steroid hormone receptor status in male breast carcinoma. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;67:333–339. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ge Y, Sneige N, Eltorky MA, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of subtypes of male breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R28. doi: 10.1186/bcr2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rudlowski C, Friedrichs N, Faridi A, et al. Her-2/neu gene amplification and protein expression in primary male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;84:215–223. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000019953.92921.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bloom KJ, Govil H, Gattuso P, Reddy V, Francescatti D. Status of HER-2 in male and female breast carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;182:389–392. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00733-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muir D, Kanthan R, Kanthan SC. Male versus female breast cancers. A population-based comparative immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:36–41. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-36-MVFB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson WF, Althuis MD, Brinton LA, Devesa SS. Is male breast cancer similar or different than female breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;83:77–86. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000010701.08825.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Golshan M, Rusby J, Dominguez F, Smith BL. Breast conservation for male breast carcinoma. Breast. 2007;16:653–656. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimitrov NV, Colucci P, Nagpal S. Some aspects of the endocrine profile and management of hormone-dependent male breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:798–807. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giordano SH, Valero V, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN. Efficacy of anastrozole in male breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:235–237. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kraybill WG, Kaufman R, Kinne D. Treatment of advanced male breast cancer. Cancer. 1981;47:2185–2189. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810501)47:9<2185::aid-cncr2820470913>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baselga J, Swain SM. Novel anticancer targets: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrc2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uberall I, Kolar Z, Trojanec R, Berkovcova J, Hajduch M. The status and role of ErbB receptors in human cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;84:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli RR, et al. ErbB-2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: implications for breast cancer. Embo J. 1996;15:254–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. Embo J. 2000;19:3159–3167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Offterdinger M, Bastiaens PI. Prolonged EGFR signaling by ERBB2-mediated sequestration at the plasma membrane. Traffic. 2008;9:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ciampa A, Xu B, Ayata G, et al. HER-2 status in breast cancer: correlation of gene amplification by FISH with immunohistochemistry expression using advanced cellular imaging system. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006;14:132–137. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000150516.75567.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee JW, Soung YH, Seo SH, et al. Somatic mutations of ERBB2 kinase domain in gastric, colorectal, and breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:57–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meng S, Tripathy D, Shete S, et al. HER-2 gene amplification can be acquired as breast cancer progresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9393–9398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402993101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bianchi S, Palli D, Falchetti M, et al. ErbB-receptors expression and survival in breast carcinoma: a 15-year follow-up study. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:702–708. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Castiglioni F, Tagliabue E, Campiglio M, Pupa SM, Balsari A, Menard S. Role of exon-16-deleted HER2 in breast carcinomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:221–232. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwong KY, Hung MC. A novel splice variant of HER2 with increased transformation activity. Mol Carcinog. 1998;23:62–68. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199810)23:2<62::aid-mc2>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pich A, Margaria E, Chiusa L. Oncogenes and male breast carcinoma: c-erbB-2 and p53 coexpression predicts a poor survival. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2948–2956. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang-Rodriguez J, Cross K, Gallagher S, et al. Male breast carcinoma: correlation of ER, PR, Ki-67, Her2-Neu, and p53 with treatment and survival, a study of 65 cases. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:853–861. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000022251.61944.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fonseca RR, Tomas AR, Andre S, Soares J. Evaluation of ERBB2 gene status and chromosome 17 anomalies in male breast cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1292–1298. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213354.72638.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Honrado E, Osorio A, Palacios J, Benitez J. Pathology and gene expression of hereditary breast tumors associated with BRCA1, BRCA2 and CHEK2 gene mutations. Oncogene. 2006;25:5837–5845. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spector NL, Blackwell KL. Understanding the mechanisms behind trastuzumab therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5838–5847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Product monograph: HerceptinΔ (trastuzumab) Genetech Inc; USA: Mar, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Product monograph: HerceptinΔ (trastuzumab) Hoffmann-La Roche Limited; 2008. Nov 4, [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gennari R, Menard S, Fagnoni F, et al. Pilot study of the mechanism of action of preoperative trastuzumab in patients with primary operable breast tumors overexpressing HER2. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5650–5655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiner LM, Adams GP. New approaches to antibody therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19:6144–6151. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hudis CA. Trastuzumab – mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:39–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Molina MA, Codony-Servat J, Albanell J, Rojo F, Arribas J, Baselga J. Trastuzumab (herceptin), a humanized anti-Her2 receptor monoclonal antibody, inhibits basal and activated Her2 ectodomain cleavage in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4744–4749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Le XF, Lammayot A, Gold D, et al. Genes affecting the cell cycle, growth, maintenance, and drug sensitivity are preferentially regulated by anti-HER2 antibody through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2092–2104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Le XF, Claret FX, Lammayot A, et al. The role of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in anti-HER2 antibody-induced G1 cell cycle arrest and tumor growth inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23441–23450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nagata Y, Lan KH, Zhou X, et al. PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Izumi Y, Xu L, di Tomaso E, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumour biology: herceptin acts as an anti-angiogenic cocktail. Nature. 2002;416:279–280. doi: 10.1038/416279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Valabrega G, Montemurro F, Sarotto I, et al. TGFalpha expression impairs trastuzumab-induced HER2 downregulation. Oncogene. 2005;24:3002–3010. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prempree T, Wongpaksa C. Mutations of HER2 gene in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(Suppl 18) (Abstract 13118) [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hynes NE, Dey JH. PI3K inhibition overcomes trastuzumab resistance: blockade of ErbB2/ErbB3 is not always enough. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lu CH, Wyszomierski SL, Tseng LM, et al. Preclinical testing of clinically applicable strategies for overcoming trastuzumab resistance caused by PTEN deficiency. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5883–5888. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nagy P, Friedlander E, Tanner M, et al. Decreased accessibility and lack of activation of ErbB2 in JIMT-1, a herceptin-resistant, MUC4-expressing breast cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2005;65:473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y, Zi X, Zhao Y, Mascarenhas D, Pollak M. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1852–1857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.24.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, Kobayashi R, Esteva FJ. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11118–11128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, et al. Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2639–2648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marty M, Cognetti F, Maraninchi D, et al. Randomized phase II trial of the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab combined with docetaxel in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer administered as first-line treatment: the M77001 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4265–4274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:719–726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Suter TM, Cook-Bruns N, Barton C. Cardiotoxicity associated with trastuzumab (Herceptin) therapy in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Breast. 2004;13:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baselga J. Herceptin alone or in combination with chemotherapy in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: pivotal trials. Oncology. 2001;61(Suppl 2):14–21. doi: 10.1159/000055397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Amar S, Roy V, Perez EA. Treatment of metastatic breast cancer: looking towards the future. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rudlowski C, Rath W, Becker AJ, Wiestler OD, Buttner R. Trastuzumab and breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:997–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carmona-Bayonas A. Potential benefit of maintenance trastuzumab and anastrozole therapy in male advanced breast cancer. Breast. 2007;16:323–325. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hayashi H, Kimura M, Yoshimoto N, et al. A case of HER2-positive male breast cancer with lung metastases showing a good response to trastuzumab and paclitaxel treatment. Breast Cancer. 2009;16:136–140. doi: 10.1007/s12282-008-0060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Available from: http://www.nccn.org.

- 102.Cancer.gov. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/malebreast.

- 103.Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:809–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD, et al. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leyland-Jones B, Gelmon K, Ayoub JP, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of trastuzumab administered every three weeks in combination with paclitaxel. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3965–3971. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McEvoy G. AHFS Drug Information. 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 109.Mackey JR, Clemons M, Cote MA, et al. Cardiac management during adjuvant trastuzumab therapy: recommendations of the Canadian Trastuzumab Working Group. Curr Oncol. 2008;15:24–35. doi: 10.3747/co.2008.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Suter TM, Procter M, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac adverse effects in the herceptin adjuvant trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3859–3865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tan-Chiu E, Yothers G, Romond E, et al. Assessment of cardiac dysfunction in a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel, with or without trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy in node-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer: NSABP B-31. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7811–7819. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, et al. Cardiac safety analysis of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1231–1238. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Konecny GE, Pegram MD, Venkatesan N, et al. Activity of the dual kinase inhibitor lapatinib (GW572016) against HER-2-overexpressing and trastuzumab-treated breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1630–1639. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Scheuer W, Friess T, Burtscher H, Bossenmaier B, Endl J, Hasmann M. Strongly enhanced antitumor activity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination treatment on HER2-positive human xenograft tumor models. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24):9330–9336. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]