Abstract

Background

Blood-derived circulatory angiogenic cells (CACs) and resident cardiac stem cells (CSCs) have both been shown to improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. The superiority of either cell type has long been an area of speculation with no definitive head-to-head trial. In this study, we compared the effect of human CACs and CSCs, alone or in combination, on myocardial function in an immunodeficient mouse model of myocardial infarction.

Methods and Results

CACs and CSCs were cultured from left atrial appendages and blood samples obtained from patients undergoing clinically indicated heart surgery. CACs expressed a broader cytokine profile than CSCs, with 3 cytokines in common. Coculture of CACs and CSCs further enhanced the production of stromal cell–derived factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor (P≤0.05). Conditioned media promoted equivalent vascular networks and CAC recruitment with superior effects using cocultured conditioned media. Intramyocardial injection of CACs or CSCs alone improved myocardial function and reduced scar burdens when injected 1 week after myocardial infarction (P≤0.05 versus negative controls). Cotransplantation of CACs and CSCs together improved myocardial function and reduced scar burdens to a greater extent than either stem cell therapy alone (P≤0.05 versus CAC or CSC injection alone).

Conclusions

CACs and CSCs provide unique paracrine repertoires with equivalent effects on angiogenesis, stem cell migration, and myocardial repair. Combination therapy with both cell types synergistically improves postinfarct myocardial function greater than either therapy alone. This synergy is likely mediated by the complimentary paracrine signatures that promote revascularization and the growth of new myocardium.

Keywords: blood cells, heart failure, myocardial infarction, stem cells

The search for cell products capable of myocardial repair has yielded a variety of candidates. In the past 10 years, circulatory angiogenic cells (CACs or early outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells) have emerged as the most promising subtype of blood-derived stem cells for myocardial repair, given their capacity to form new blood vessels (vasculogenesis) while stimulating existing blood vessels to expand (angiogenesis) through paracrine stimulation.1 As a result, this promising cell candidate is under investigation in a variety of clinical trials.2,3

Cardiac stem cells (CSCs) have also emerged as an attractive cell candidate for myocardial repair because they offer an autologous cell product genetically preprogrammed to form heart tissue.4 When injected into animal models of cardiac damage, CSCs differentiate into new working heart tissue and provide functional improvements.5 Data from phase 1 studies confirm preclinical experience and have provided the impetus for recently started phase 2 trials.6,7 But despite clear evidence of benefit after cell transplantation, long-term retention of cells is modest (<5% at 3 weeks), regardless of persistent functional benefits.8 These data hint that a sizable portion of myocardial repair is mediated by paracrine stimulation of endogenous repair or myocardial salvage mechanisms.9

Although both CAC and CSC transplantation provide myocardial repair, speculation remains as to which cell source is superior. To provide a real-world context, this study will compare the effect of primary cultured human CACs and CSCs on myocardial function after delayed injection into an immunodeficient mouse model of myocardial ischemia. Both cell sources will be cultured from cardiac patients undergoing clinically indicated procedures and reflect the target population currently enrolled in clinical trials. The fundamental mechanisms underlying cell-mediated benefits will be contrasted by comparing angiogenic and paracrine profiles. Given the disparate ontogeny and possible mechanism of benefit, the effects of combination therapy will be explored to discover whether coadministration of both cell types is detrimental, ineffectual, or synergistic.

Methods

See the expanded methods section (online-only Data Supplement) for more details.

Cell Culture and Conditioned Media

Human CACs and CSCs were cultured from tissue samples obtained from patients undergoing clinically indicated heart surgery after informed consent. All protocols were approved by the University of Ottawa Heart Institution Research Ethics Board. CSCs were cultured using standard culture techniques described previously.10 CACs were isolated from peripheral blood samples using standard techniques.2,11 Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDFs) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells were cultured according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Conditioned media was obtained from CSCs, CACs, and NHDFs after 48 hours of culture in low serum basal media under hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen) to simulate the environment of the infarcted myocardium. Cocultures of CACs and CSCs were seeded at 3 confluency ratios (CSClow/CAChigh; CSChigh/CAClow; CSChigh/CAChigh) to examine the relationship between CACs and CSCs under coculture conditions.

In Vitro Cytokine Expression

Cytokine secretion in conditioned media was screened using a custom protein array (RayBiotech, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Cytokines of interest were confirmed using ELISA. All immunosorbent measures were normalized to the protein content and media volume.

In Vitro Angiogenic Differentiation and Cell Migration

The capacity of CACs and CSCs to stimulate angiogenic growth was assessed using a growth factor–depleted matrigel assay (Millipore) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Six random fields were analyzed, and cumulative tubular growth was determined. The ability of conditioned media to recruit CACs was assessed using transwell plates (3.0 μm pores; Corning). CACs that had successfully migrated through the polycarbonate membrane were fixed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich). Fluorescent microscopy was used to determine the average number of cells per random field.

Myocardial Infarction, Cell Injection, and Functional Evaluation

Myocardial infarctions were performed in male NOD-SCID mice by permanent ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. Seven days after ligation, stem cells and controls were injected into the myocardium along the infarct border and at the cardiac apex using transthoracic echocardiographic guidance (VisualSonics). Left ventricular ejection fraction was evaluated 21 and 28 days after LAD ligation to assess the functional effects of each cell therapy. Long-term effects of cell therapy were evaluated in a subset of mice from each group (n=4). All functional evaluations were conducted and analyzed by investigators blinded to the animal’s treatment group. After the last assessment of myocardial function, the mice were euthanized and hearts excised for histology or quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

Quantitative PCR Analysis

Myocardial retention of transplanted cells was assessed in a subset of mice (n=3/group) using quantitative PCR for noncoding human alu repeats.12 Left ventricular genomic DNA was extracted, and quantitative PCR was performed with transcript-specific hydrolysis primer probes.

Histology

Tissue viability was assessed after staining with Masson trichrome (Invitrogen). Stem cell engraftment, capillary density, and differentiation were assessed through immunohistochemistry. For these measures, 3 sections were analyzed per animal and averaged with ≥3 animals per group.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean±SEM. To determine whether differences existed within groups, data were analyzed by a 1-way or repeated-measures ANOVA (SPSS v20.0.0); if such differences existed, Bonferroni-corrected t test was used to determine the groups with the differences. In all cases, variances were assumed to be equal, and normality was confirmed before further post hoc testing. Differences in categorical measures were analyzed using a χ2 test. A final value of P≤0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Baseline Demographics

Fifty-three patients (69% men; age, 68±2 years; body mass index, 29±1 kg/m2; Table I in the online-only Data Supplement) were enrolled in the study. All patients had a history of stable cardiac disease with numerous cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes mellitus (37%), hypertension (74%), and dyslipidemia (65%). The majority of patients had a history of coronary artery disease (75%), myocardial infarction (22%), valvular heart disease (31%), and congestive heart failure (31%). The majority of patients underwent elective cardiac surgery for coronary bypass alone (65%), with the remainder undergoing valve repair/replacement alone (25%) or coronary bypass with valve repair/replacement (10%). No patient had experienced an acute coronary syndrome or admission for congestive heart failure for 6 months before sample collection. All patients were on stable cardiac medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (82%), antiplatelet therapy (75%), β-blockers (69%), and statins (61%) for ≥6 months before surgery. Although the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients were similar, notable exceptions included a tendency for better renal function (1.2±0.1 versus 0.9±0.1 mL/min; P≤0.05) and worse chronic stable angina (Canadian Cardiovascular Society class 1.2±0.1 versus 0.3±0.2; P≤0.05) in patients who donated samples for the in vivo study.

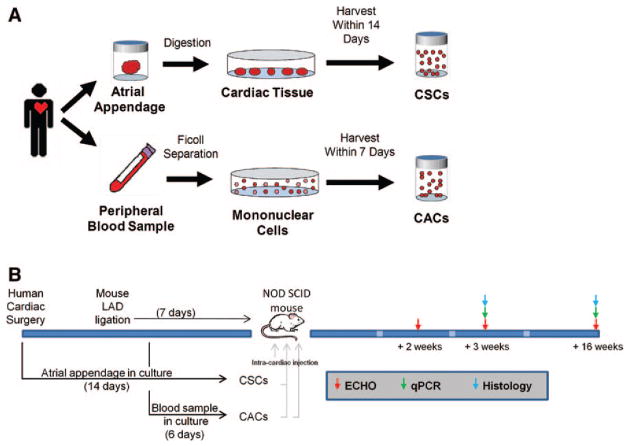

Atrial appendage specimens were collected at the time of cardiac surgery and began processing within 1 hour of harvest. To provide an unbiased comparison of CAC and CSC efficacy, blood samples for in vitro testing were collected at the time of cardiac surgery (Figure 1). In deference to a clinically translatable protocol and the different times required for stem cell culture (6 versus 14 days), blood samples for in vivo testing were collected 8 days after cardiac surgery. Flow cytometry of representative collections of both cell types demonstrated characteristic proportions of CAC and CSC identity markers (Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement). Age and other comorbidities were not found to influence overall culture yield.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. A, Schematic representation of the culture protocol for circulatory angiogenic cells (CACs) and cardiac stem cells (CSCs). B, Schematic outlining the timing of the cell culture with animal surgeries, cell transplantation, and outcome measures. LAD indicates left anterior descending; and qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Human CACs Express a Broader Cytokine Profile Than Human CSCs

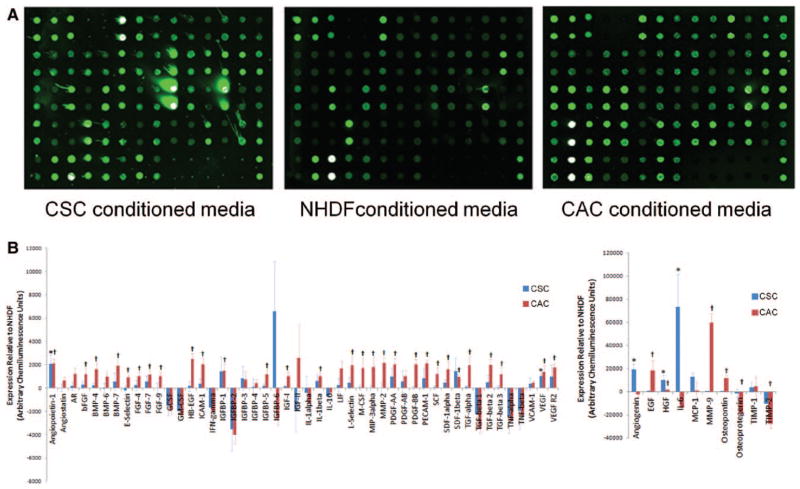

The paracrine profile of human CSCs, CACs, and NHDFs was screened using conditioned media with a custom protein array. This array returned a proportional fluorescent signal for the 59 cytokines tested with 2 technical repeats (Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement). Figure 2 demonstrates 3 representative blots from human CSCs, CACs and NHDFs. As shown in Figure 2B, both CACs and CSCs produced a large number of growth factors in excess to NHDF (36 and 5 cytokines; P≤0.05 versus cytokine levels detected within NHDF-conditioned media). Interestingly, the paracrine profile of CACs was significantly broader than CSCs (χ2 value, 3.93; P≤0.05 versus the expected frequency of cytokines elevated in stem cell–conditioned media), with rare instances of the same growth factor being overexpressed by both cell types (angio-poetin-1, hepatocyte growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor).

Figure 2.

Growth factors produced by circulatory angiogenic cells (CACs), cardiac stem cells (CSCs), and normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDFs) under hypoxic culture conditions. A, Representative images of the custom protein array used to screen conditioned media from CACs, CSCs, and NHDFs. Densitometry values were run in duplicates on the same array (Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement). B, Densitometry analysis of growth factors produced by CACs (n=6) and CSCs (n=8) compared with NHDF (n=7). *P≤0.05 for CSCs vs NHDF; †P≤0.05 for CACs vs NHDF. AR indicates androgen receptor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GCSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HB-EFG, heparin binding epidermal growth factor; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; IFN, interferon; IGFBP, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IL, interleukin; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PECAM, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule; SCF, stem cell factor; SDF, stromal cell-derived factor; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; and VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

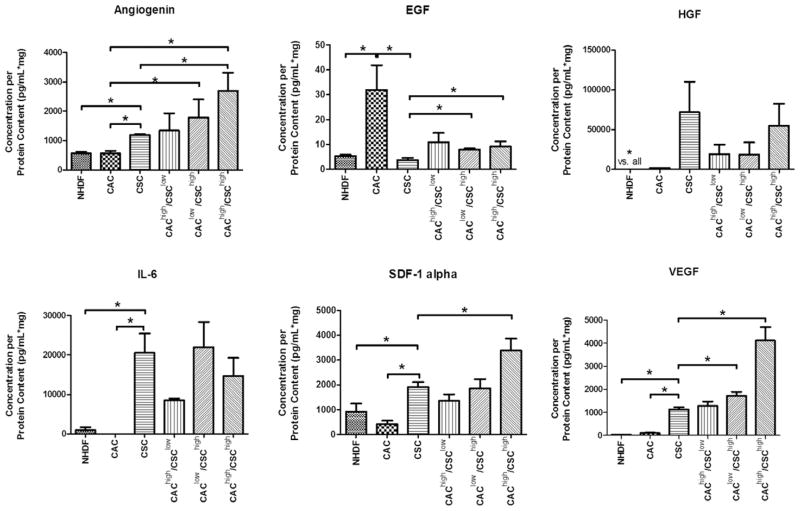

Confirmatory ELISA analysis was performed on select cytokines based on high levels of expression or literature supporting a key role in postinfarct repair (Figure 3). These assays confirmed that CSCs produced greater amounts of angiogenin, hepatocyte growth factor, interleukin-6, stromal cell–derived factor-1α, and vascular endothelial growth factor, whereas CACs produced greater amounts of epidermal growth factor. The possibility that different combinations of cell types may interact to influence growth factor secretion was analyzed using cocultures at different confluency ratios. These combination cocultures corresponded to half the number of cells used in either single stem cell system (CSClow/CAChigh 5.0×104/1.5×106; CSChigh/CAClow 1.0×105/7.5×105; CSChigh/CAChigh 1.0×105/1.5×106). Combination culture did not provide additional production of epidermal growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor under all 3 coculture conditions (P≤0.05 versus single cultures), whereas angiogenin, stromal cell–derived factor-1α, and vascular endothelial growth factor were all produced in an incremental fashion (P≤0.05 versus single cultures). These data suggest that important costimulation occurs between the different cell types, which may increase the potency of combination therapy when CACs and CSCs are administered together.

Figure 3.

Influence of circulatory angiogenic cell (CAC) and cardiac stem cell (CSC) coculture on growth factor production under hypoxic conditions. The effect of varying CSC/CAC populations was investigated using different confluency ratios that corresponded to half the number of cells used in either single stem cell system. *P≤0.05; n=4 samples per assay. EGF indicates epidermal growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IL, interleukin; NHDF, normal human dermal fibroblasts; SDF, stromal cell-derived factor; and VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

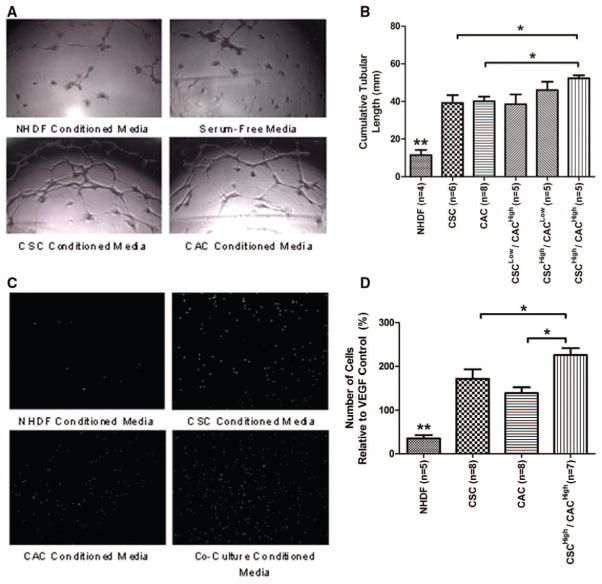

Human CACs and CSCs Increase Angiogenesis and Cell Migration

The capacity of human CACs and CSCs to form blood vessels was assessed by exposing umbilical vein endothelial cells to stem cell–conditioned media within a growth factor–depleted matrigel assay (Figure 4). Media conditioned from CAC and CSC cultures stimulated vessel formation to a similar extent (P=ns). Conditioned media from cocultures demonstrated an additive effect with more tubule formation (P≤0.05). Conditioned media from CAC and CSC cultures attracted CACs to a similar extent (P=ns), whereas conditioned media from CSC/CAC cocultures showed a greater capacity to attract CACs than either single culture alone (P≤0.05). These results suggest that CSC and CACs have a similar capacity to support angiogenesis, whereas coculture further enhances this effect.

Figure 4.

Proangiogenic effects of circulatory angiogenic cells (CACs) and cardiac stem cells (CSCs). A, Representative images of matrigel-cultured umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) exposed to conditioned media from CACs, CSCs, normal human dermal fibroblast (NHDF), and serum-free controls. B, Cumulative tubular length analysis demonstrates greater vessel formation in stem cell–conditioned media compared with the negative cellular control. Conditioned media from the coculture of CACs and CSCs further enhanced HUVEC vessel formation. C, Representative images of CACs after migration through the transwell filter when exposed to conditioned media from CACs, CSCs, NHDF, and CSC/CAC cocultures. D, Analysis of the number of cells that migrated through the transwell filter after exposure to conditioned media and normalized to unbiased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)–alone stimulation. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.05 compared with all other cell cultures.

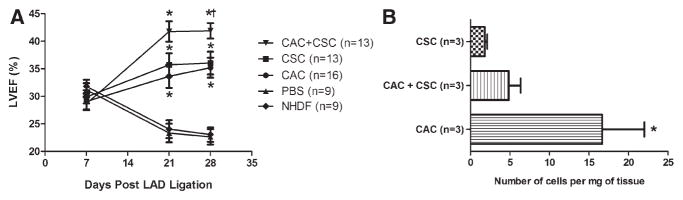

Human CACs and CSCs Provide Equivalent Myocardial Repair With Superior Benefits Using Combination Therapy

The effect of human CACs and CSCs alone or in combination was assessed after intramyocardial injection into an immuno-deficient mouse model of myocardial ischemia. As shown in Figure 5A, animals treated with CACs or CSCs alone had a greater ejection fraction (37±2% and 36±2%, respectively) 3 weeks after LAD ligation than animals treated with NHDF or PBS (22±2% and 23±1%, respectively; P≤0.05). These benefits were maintained in both individual treatment groups 3 months after LAD ligation (37±2% and 36±2%, respectively; Table II in the online-only Data Supplement). In a manner consistent with the in vitro data, cotransplantation of CACs and CSCs provided greater myocardial repair 3 weeks after LAD ligation compared with injection with either cell type alone (Figure 5A). Long-term data from a subset of mice (n=4) suggest that these effects are sustained (P=ns, +28 days versus +16 weeks after LAD ligation left ventricular ejection fraction) compared with the progressive marked decline in the PBS treatment group (+16-week ejection fraction P≤0.05 compared with CAC or CSC-alone treatment; Figure IIIA in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 5.

Effects of circulatory angiogenic cell (CAC) and cardiac stem cell (CSC) treatment on myocardial repair and survival. A, Comparison of the effect of cell treatment on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). *P≤0.05 vs normal human dermal fibroblast (NHDF) or PBS controls using repeated ANOVA; †P≤0.05 vs CAC or CSC alone using repeated ANOVA. B, Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for human alu sequences demonstrating modest long-term engraftment of transplanted cells. *P≤0.05 vs CSC alone. LAD indicates left anterior descending.

These functional benefits occurred despite modest retention of injected cells (Figure 5B). Furthermore, despite equivalent degrees of myocardial repair, fewer CSCs were found 21 days after intramyocardial injection compared with CACs (0.5±0.1% versus 3.6±1.1%; P<0.05). Combination therapy with both CACs and CSCs did not enhance engraftment or cell retention 21 days after injection (P=ns), although superior effects on myocardial repair were observed. Long-term engraftment data demonstrated that although human CSCs continued to persist in the mouse myocardium CAC retention dwindled to comparable numbers by 16 weeks after transplantation (Figure IIIB in the online-only Data Supplement). Taken together, these data hint that the benefits observed with first-generation CAC and CSC products are independent of long-term myocardial retention and reflect the contribution of growth factors delivered in the first weeks after cell injection.

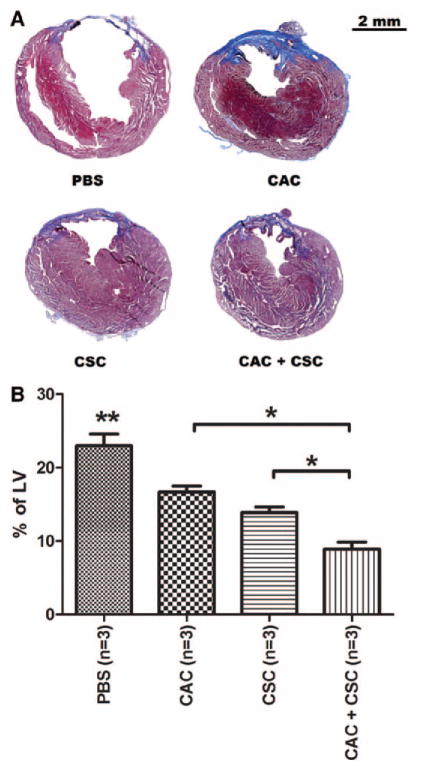

Transplantation of Human CAC and CSCs Reduce Ventricular Scar Burden With Superior Effects Using Combination Therapy

Scar formation and tissue viability within the infarct zone were analyzed using Masson trichrome–stained sections 21 days after stem cell injection (Figure 6). Both CAC and CSC transplantation reduced scar formation compared with PBS-treated animals (16.7±1.0% and 13.9±0.8% versus 23.0±1.6%, respectively; P≤0.05). CSC therapy alone prevented scar formation to a greater degree compared with CAC-treated animals (P≤0.05), despite equivalent effects on myocardial function. Transplantation of both cell types in combination reduced ventricular scar burden to a greater degree compared with either cell type alone (8.9±1.0%; P≤0.05). Cell-mediated effects on ventricular scarring were sustained over long-term follow-up (Figure IV in the online-only Data Supplement). CAC- and CSC-treated animals demonstrated a significantly higher capillary density within the peri-infarct region compared with PBS-treated controls (27.8±3.2% and 22.2.9±2.1% versus 15.1±2.2%, respectively; P≤0.05). Although single-cell therapies yielded comparable capillary densities, combination cell therapy improved capillary density over all treatment groups (42.6±2.2%; P≤0.05; Figure V in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 6.

Effects of circulatory angiogenic cell (CAC) and cardiac stem cell (CSC) transplantation on ventricular scar burden after left anterior descending ligation. A, Representative histology images from each stem cell treatment 28 days after myocardial infarction demonstrating scar burden using Masson trichrome satin. B, Quantification of the scar tissue present in the left ventricle (LV) 28 days after myocardial infarction. *P≤0.05 vs single-cell therapies; **P≤0.05 vs CACs or CSCs or CAC+CSCs.

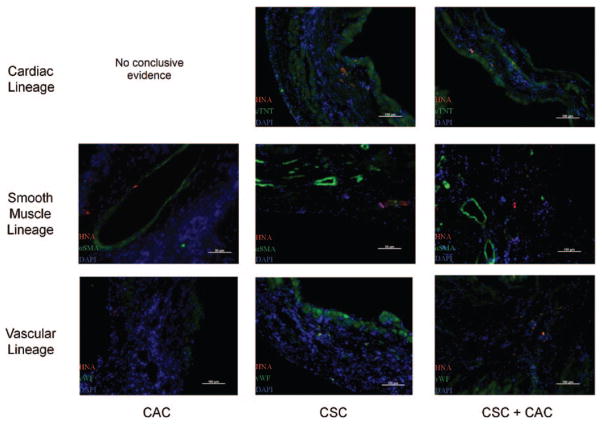

Small Clusters of Differentiated Human Cells Persist Within the Infarct and Peri-infarct Regions

To evaluate stem cell engraftment and differentiation, histological sections were labeled with human nuclear antigen in conjunction with cardiac lineage markers (smooth muscle [α-smooth muscle actin], vascular [Von Willebrand factor], and myocyte [cardiac troponin T]; Figure 7). Small clusters of human cells were identified 21 days after stem cell transplantation in each treatment group within the peri-infarct region, as well as the infarct itself. This indicated that each stem cell treatment provided cells capable of engrafting and differentiating into functional cells within the damaged myocardium, albeit at a modest degree. Animals transplanted with human CACs alone had only human cells of vascular identity found on follow-up histology (Figure VI in the online-only Data Supplement). In contrast, animals treated with either CSCs alone or combination of CACs+CSCs had human cells of all 3 lineages found, demonstrating the inherent multilineage potential of CSCs

Figure 7.

Clusters of differentiated human cells persist within the peri-infarct and infarct regions. Representative images of each stem cell–treated group demonstrating human cells that cosegregate with markers of cardiac lineage. αSMA indicates α-smooth muscle actin; CAC, circulatory angiogenic cell; CSC, cardiac stem cell; cTnT, cardiac troponin; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HNA, human nuclear antigen; and vWF, Von Willebrand factor.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the 2 leading clinical candidates for cell-mediated cardiac repair provide unique paracrine repertoires with equivalent effects on angiogenesis, stem cell migration, and myocardial repair. Combination therapy with both first-generation cell products synergistically improved postinfarct myocardial function greater than either therapy alone. This synergy is likely mediated by the complimentary paracrine signatures that promote revascularization, tissue salvage, and the growth of new myocardium.

Given that these 2 cell types represent the 2 leading autologous cell sources in phase 1 and 2 cardiac repair trials, we chose to contrast cell products from patients undergoing clinically indicated cardiac surgery, precisely the same patients enrolled in current trials and in need of cellular cardiomyoplasty in the future. To provide an unbiased comparison of stem cell potency, in vitro experiments contrasted CACs and CSCs acquired at the time of cardiac surgery. The in vivo study was designed such that atrial appendages were acquired at the time of cardiac surgery, whereas CAC blood draws were performed 9 days after surgery. This strategy reflects the logistical realities inherent in cell culture and the administration of an autologous cell product soon after myocardial infarction. Although this approach may have favored CAC function and viability,11,13 this bias is tempered by the observation that (1) the effects of vascular damage on CAC function are very transient, (2) the results observed in both the in vivo and in vitro experiments are consistent, and (3) the phenotypic profile of both injected cells sources is consistent with those used in clinical trials (Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement). The CSC product used in this study represents the ultimate simplification of CSC culture before antigenic selection4 or subculture.5,14 This product has been shown to provide equivalent repair to established cell products with hints of superiority.10,15

The current work extends previous studies by providing the first unambiguous head-to-head comparison of autologous CACs and CSCs from clinical patients. Although earlier work from our laboratory demonstrated that expanded populations of CSCs from human cardiac samples secrete significant quantities of vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and hepatocyte growth factor, we used a wide-ranging cytokine protein array to show that CSCs also secrete significant amounts of angiopoietin-1, angiogenin, and inter-leukin-6.9,10 Interestingly, the CSC paracrine signature had few overlap cytokines with the more elaborate CAC paracrine profile. Despite these differences, the angiogenic response to conditioned media was similar between the 2 cells types, suggesting this plays an important role in cardiac repair. Although CSCs differentiated more readily into a cardiac phenotype, effects on cardiac repair were equivalent. This result may be explained by the PCR engraftment data demonstrating modest long-term retention (<1% of transplanted cells detected 3 weeks after injection). Despite this finding, long-term (+16 weeks after LAD ligation) benefits are sustained notwithstanding low numbers of injected cells. These data suggest that the benefits after CAC and CSC transplantation occur immediately on injection, and the persistence of large numbers of injected cells may not be necessary for sustained effects on myocardial repair, but this requires further testing to fully validate.

Given the number of CSC candidates of dissimilar ontogeny, it follows that treatment with complimentary cell types may provide synergistic benefits. The limited published data to date support this notion because treatment with nonclinically relevant cell types (ie, angiogenic cells+skeletal myoblasts or epicardium-derived cells+cardiac progenitor cells) demonstrates superior effects when combination cell products are injected.16,17 This report confirms this notion and provides direct evidence that application of the 2 leading preclinical agents for myocardial repair provides synergistic benefits when applied after myocardial infarction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Operating Grant 229694). Dr Davis is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Clinician Scientist Award).

Footnotes

Presented at the 2012 American Heart Association meeting in Los Angeles, CA, November 3–7, 2012.

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://circ.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000374/-/DC1.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Cho HJ, Lee N, Lee JY, Choi YJ, Ii M, Wecker A, Jeong JO, Curry C, Qin G, Yoon YS. Role of host tissues for sustained humoral effects after endothelial progenitor cell transplantation into the ischemic heart. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3257–3269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taljaard M, Ward MR, Kutryk MJ, Courtman DW, Camack NJ, Goodman SG, Parker TG, Dick AJ, Galipeau J, Stewart DJ. Rationale and design of Enhanced Angiogenic Cell Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction (ENACT-AMI): the first randomized placebo-controlled trial of enhanced progenitor cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2010;159:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BAMI. The effect of intracoronary reinfusion of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNC) on all cause mortality in acute myocardial infarction. [Accessed April 2, 2012];ClinicalTrials.gov. 2 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK, Hare JM, Messina E, Giacomello A, Abraham MR, Marbán E. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation. 2007;115:896–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LE, Berman D, Czer LS, Marbán L, Mendizabal A, Johnston PV, Russell SD, Schuleri KH, Lardo AC, Gerstenblith G, Marbán E. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): a prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D’Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, Beache GM, Wagner SG, Leri A, Hosoda T, Sanada F, Elmore JB, Goichberg P, Cappetta D, Solankhi NK, Fahsah I, Rokosh DG, Slaughter MS, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Terrovitis J, Lautamäki R, Bonios M, Fox J, Engles JM, Yu J, Leppo MK, Pomper MG, Wahl RL, Seidel J, Tsui BM, Bengel FM, Abraham MR, Marbán E. Noninvasive quantification and optimization of acute cell retention by in vivo positron emission tomography after intra-myocardial cardiac-derived stem cell delivery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li TS, Gerstenblith G, Messina E, Giacomello A, Marbán E. Relative roles of direct regeneration versus paracrine effects of human cardiosphere-derived cells transplanted into infarcted mice. Circ Res. 2010;106:971–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis DR, Kizana E, Terrovitis J, Barth AS, Zhang Y, Smith RR, Miake J, Marbán E. Isolation and expansion of functionally-competent cardiac progenitor cells directly from heart biopsies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruel M, Suuronen EJ, Song J, Kapila V, Gunning D, Waghray G, Rubens FD, Mesana TG. Effects of off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting on function and viability of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz JR, Stoutenger BR, Robinson AP, Spees JL, Prockop DJ. Human stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow promote neurogenesis of endogenous neural stem cells in the hippocampus of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18171–18176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508945102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill M, Dias S, Hattori K, Rivera ML, Hicklin D, Witte L, Girardi L, Yurt R, Himel H, Rafii S. Vascular trauma induces rapid but transient mobilization of VEGFR2(+)AC133(+) endothelial precursor cells. Circ Res. 2001;88:167–174. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, Morrone S, Chimenti S, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, Battaglia M, Latronico MV, Coletta M, Vivarelli E, Frati L, Cossu G, Giacomello A. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:911–921. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li TS, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Smith RR, Zhang Y, Sun B, Matsushita N, Blusztajn A, Terrovitis J, Kusuoka H, Marbán L, Marbán E. Direct comparison of different stem cell types and subpopulations reveals superior paracrine potency and myocardial repair efficacy with cardiosphere-derived cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:942–953. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guarita-Souza LC, Carvalho KA, Woitowicz V, Rebelatto C, Senegaglia A, Hansen P, Miyague N, Francisco JC, Olandoski M, Faria-Neto JR, Brofman P. Simultaneous autologous transplantation of cocultured mesenchymal stem cells and skeletal myoblasts improves ventricular function in a murine model of Chagas disease. Circulation. 2006;114(1 suppl):I120–I124. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter EM, van Oorschot AA, Hogers B, van der Graaf LM, Doevendans PA, Poelmann RE, Atsma DE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Goumans MJ. A new direction for cardiac regeneration therapy: application of synergistically acting epicardium-derived cells and cardiomyocyte progenitor cells. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:643–653. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.843722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.