Abstract

Transplantation of ex vivo proliferated cardiac stem cells (CSCs) is an emerging therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy but outcomes are limited by modest engraftment and poor long-term survival. As such, we explored the effect of single cell microencapsulation to increase CSC engraftment and survival after myocardial injection. Transcript and protein profiling of human atrial appendage sourced CSCs revealed strong expression the pro-survival integrin dimers αVβ3 and α5β1- thus rationalizing the integration of fibronectin and fibrinogen into a supportive intra-capsular matrix. Encapsulation maintained CSC viability under hypoxic stress conditions and, when compared to standard suspended CSC, media conditioned by encapsulated CSCs demonstrated superior production of pro-angiogenic/cardioprotective cytokines, angiogenesis and recruitment of circulating angiogenic cells. Intra-myocardial injection of encapsulated CSCs after experimental myocardial infarction favorably affected long-term retention of CSCs, cardiac structure and function. Single cell encapsulation prevents detachment induced cell death while boosting the mechanical retention of CSCs to enhance repair of damaged myocardium.

Keywords: Heart failure, Myocardial infarction, Encapsulation, Cell therapy

1. Introduction

While mechanical interventions and pharmaceuticals have reduced the mortality associated with myocardial infarction, survivors are often left with significant damage and chronic heart failure [1]. Recently, transplantation of ex vivo proliferated cardiac stem cells (CSC) has garnered attention as a promising means of improving left ventricle function while reducing infarct size [2,3]. Despite these developments, the full capacity of CSCs to repair myocardium is limited by modest retention immediately after transplant into the vascular heart which, in part results in very low long term survival [4,5]. This notion is supported by several recent papers demonstrating early CSC engraftment predicts later cardiac recovery from myocardial infarction while methods targeted towards boosting the early retention of transplanted cells enhance cells-mediated cardiac repair [6–9]. These measures address the challenge to acutely retain injected cells within a vascular organ by reducing mechanical extrusion from the myocardium and clearance through lymphatic or venous drainage [10,11]. But once cells are acutely retained in damaged myocardium, ongoing cell death ensues as the suspended cells have lost vital integrin-dependent attachments to the extracellular matrix (ECM)(12) which reduces stimulation of pro-survival pathways and results in detachment-induced programmed cell death (or anoikis) [13,14].

The objective of this work is to increase the survival of ex vivo proliferated CSCs during the suspension period that precedes cardiac transplantation to boost acute engraftment. Molecular profiling of the CSC adhesion molecules will permit the rationale design of a supportive three-dimensional hydrogel capsule to increase acute retention of transplanted cells and militate against anoikis. We hypothesize that encapsulation will improve acute retention of CSCs by preventing mechanical clearance from the heart while protecting against anoikis. Ultimately, our goal is to provide cocooned cells with the opportunity to survive, mobilize and repair infarcted myocardium.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients and cell culture

Human CSCs were cultured from the atrial appendages obtained from patients undergoing clinically-indicated surgery using established methods (Fig. 2A) [15]. Briefly, tissue sections were minced and digested prior to being placed in cardiac explants media (CEM; Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Invitrogen), 20% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), 2 mmol/l L-glutamine (Invitrogen) and 0.1 mmol/l 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen). After seven days in culture, the heterogeneous population of cells that spontaneously emigrated from the plated tissue was harvested using mild trypsinization (0.05% trypsin; Invitrogen). Circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) were isolated from peripheral blood samples donated by patients undergoing clinically indicated coronary angiography as previously described [16]. Using density-gradient centrifugation (Histopaque 1077; Sigma–Aldrich), mononuclear cells were isolated and cultured in endothelial media (EBM-2, 2% FBS, 50 ng/ml human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), 50 ng/ml human insulin-like growth factor-1 and 50 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor; Clonetics). One week later, CACs were harvested and used for experimentation. Cell viability was quantified using a colorimetric WST-8 dehydrogenase assay (CCK-8; Dojindo). A trypan blue stain was used to identify cell death (Sigma–Aldrich).

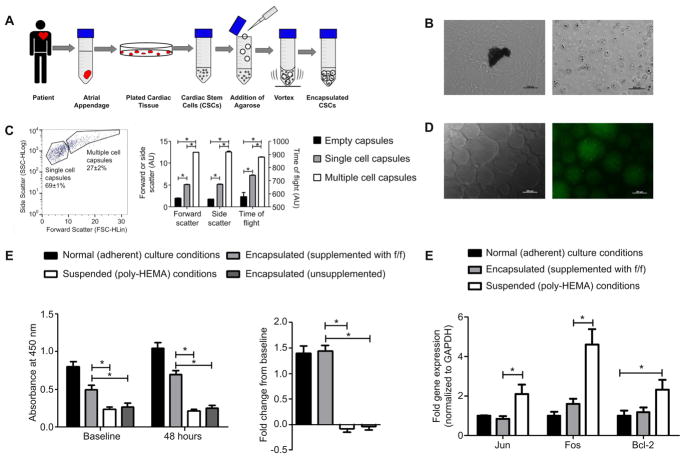

Fig. 2.

Method of encapsulation and in vitro characterization. (A): Atrial appendages obtained from patients undergoing clinically indicated cardiac surgery. (B): After 7 days in culture, CSCs were harvested from the spontaneous outgrowth surrounding the plated cardiac tissue (left) and encapsulated CSCs in a matrigel cocoon (right) (C): FACS analysis of capsule size (D): fluorescent microscopy of empty matrigel capsules supplemented with Oregon-green fibrinogen. (E): CSC viability using CCK-8 at baseline (16 h) and after 48 h in culture; n = 3 (left) and proliferation of CSCs represented by the fold change after 48 h in culture; n = 3 (right) (F): qPCR analysis of the expression patterns of pro-survival transcripts (Jun, Fos and Bcl-2) after 48 h in culture; data expressed as the relative gene expression normalized to Gapdh; n = 3/gene.

2.2. Cell encapsulation

Human CSCs were harvested and suspended in media and mixed with low melt agarose (Sigma–Aldrich). The agarose was supplemented with human fibronectin (Sigma–Aldrich) or human fibrinogen (Sigma–Aldrich) as indicated. To form capsules, the cell/matrigel mixture was added drop-wise to agitated dimethylpolysiloxane (Sigma–Aldrich) and then rapidly cooled using a combination of cold HBSS and ice. The mixture was then centrifuged and capsules were filtered from the coalesced hydrogel using a 100 μm filter (Fischer Scientific) and were re-suspended in appropriate media for testing. The capacity of immobilized matrix proteins to incorporate into matrigel capsules was verified using Oregon-green conjugated fibrinogen (Invitrogen). Fibrinogen was visualized in empty capsules under the fluorescent microscope (Zeiss Observer.A1 Axio) at 470 nm to demonstrate protein localization (Fig. 2D).

2.3. Integrin profile expression

The admixture of CSCs harvested from the plated tissue was sorted using a FAC-SAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with isotype matched immunoglobulin antibodies used as controls (c-kit, 9816-11, Southern Biotech; CD90 (BD Biosciences). Total RNA was extracted using PARIS™ RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen) and treated with 2U DNase I (Invitrogen) for 15 min at room temperature to eliminate genomic DNA. From 0.5 μg total RNA, first strand cDNA synthesis was performed using GoScript™ reverse transcriptase (Promega) and 0.5 μg random hexamer primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) for 1 h at 40 °C. With gene specific primers designed using DNAMAN software (Lynnon Biosoft) and primer3 (v.0.4.0; Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000), target gene mRNA levels were assessed by RT-qPCR using BRYT Green GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) and a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system (Roche). Relative changes in mRNA expression of target genes were determined using the Δ-ΔCt method normalized against 18S and Gapdh [17]. Western blot analysis was used to look at protein expression of integrins in c-Kit+/CD90-, c-Kit-/CD90- and c-Kit-/CD90- sub-populations. Representative bands shown were traced from different blots; densitometry was normalized to the corresponding Gapdh from each blot.

2.4. Pro-survival gene expression

RNA was extracted from CSCs after 48 h of culture in adherent, encapsulated or suspended conditions using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Activation of attachment mediated pro-survival pathways (AKT, ERK, and JNK) was quantified by RT-qPCR expression of downstream targets (BCL-2, FOS, and JUN) using qPCR Master Mix (Roche) and a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system (Roche). Relative changes in mRNA expression of target genes were determined using the Δ – ΔCt method normalized to Gapdh [17].

2.5. Conditioned media for angiogenesis, CAC migration and paracrine profiling

Conditioned media was obtained from adherent, encapsulated and suspended CSCs after 48 h of culture in hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen). Cells were seeded at 90% confluency in low serum basal media (Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium, 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mmol/l L-glutamine and 0.1 mmol/l 2-mercaptoethanol) on 6-well plates (Corning). The influence of single cell encapsulation upon the paracrine signature of CSC was verified by comparing conditioned media using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assays (R&D Systems, USA; angiogenin (DAN00), interleukin-6 (IL-6; D6050), stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α; DSA00) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; DVE00)). The capacity of encapsulated CSCs to promote angiogenesis assessed using a growth factor depleted matrigel assay (ECM625, Millipore) as directed by the manufacturer’s instructions. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were seeded on matrigel with stem cell conditioned media (adherent, encapsulated or suspended) or serum free DMEM supplemented with 100 μM VEGF (positive media control). After 18 h of incubation, random fields (10× magnification, 5 random fields) were sampled using phase contrast microscopy. Cumulative tubular growth was determined using Image J software plug-in, NeuronJ (National Institutes of Health (NIH); http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). The effects of single cell encapsulation upon stem cell recruitment was assessed using fibronectin coated trans-well plates (24 wells, 3.0 μm pores; Corning) with 3.0 × 104 CACs plated in the upper well in serum-free DMEM while conditioned media (adherent, encapsulated or suspended) was placed in the bottom well. Serum free DMEM containing 100 ng VEGF was used as an unbiased control to normalize individual variations in CAC migration. After 24 h of normoxic incubation, the inserts and the remaining upper compartment CACs were removed. CACs that had successfully migrated through the polycarbonate membrane were fixed (4% para-formaldehyde) and stained with DAPI (Sigma–Aldrich). Fluorescent microscopy (10× magnification, 6 random fields) was used to determine the average number of cells per random field (Image J, ICTN plug-in, Center for Bio-Image).

2.6. Myocardial infarction, cell injection, and functional evaluation

The ability of encapsulated human CSC to promote myocardial retention and influence cardiac repair was assessed using male NOD-SCID mice (8–9 weeks old) after left anterior descending artery ligation. One week after LAD ligation, mice were injected with 1 × 105 encapsulated CSCs (3% agarose), 1 × 105 suspended (non-encapsulated) CSCs, or the negative vehicle control (PBS) with injections split between the cardiac apex and lateral infarct border zone. Twenty one and 28 days after LAD ligation, the effect of cell therapy was evaluated from the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; VisualSonics V1.3.8, VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada). The myocardial retention of transplanted cells was assessed 1 h and 28 days after LAD ligation in a subset of mice using qPCR for non-coding human ALU repeats. Genomic DNA was extracted (DNeasy kit; Qiagen) from the excised heart and qPCR was performed using transcript specific hydrolysis primer probes. Cell number was derived from standard curves normalized to the mass sampled and was expressed as a percentage of the cell count delivered or the number of cells detected 1 h after injection.

2.7. Histology

After the final assessment of myocardial function, the hearts were excised, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in OCT and sectioned. Tissue viability within the infarct zone was calculated from Masson’s trichrome (Invitrogen) stained sections by tracing the infarct borders manually and then using ImageJ software to calculate the percent of viable myocardium within the overall infarcted area. CSC engraftment was confirmed by staining sections for human nuclear antigen (HNA; SAB4500768, Sigma–Aldrich) and differentiation to a cardiac lineage was identified by staining with α-SMA (ab125266; Abcam), cTnT (ab66133; Abcam) and vWF (11778-1-AP; Proteintech Group).

2.8. Statistical analysis

All data is presented as mean ± SEM. To determine if differences existed within groups, data was analyzed by a one-way ANOVA; if such differences existed, Bonferroni’s corrected t-test was used to determine the group(s) with the difference(s) (SPSS v20.0.0). Differences in categorical measures were analyzed using a Chi Square test. A final value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. All probability values reported are 2-sided.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline patient demographics

Nineteen patients (79% male; age 65 ± 10 years; BMI 28 ± 5 kg/m2, Supplement Table S1) were enrolled in the study. All patients had a history of stable cardiac disease with several cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes (32%; HbA1c 6.0 ± 0.1%), hypertension (68%), dyslipidemia (68%) and ongoing smoking (58%). The majority of patients underwent elective cardiac surgery for coronary bypass alone (68%) with the remainder undergoing valve repair/replacement alone (11%) or coronary bypass with valve repair/replacement (21%). The patients who donated atrial appendages for the in vivo study tended to have fewer co-morbidities (less ongoing smoking and peripheral vascular disease) while requiring less cardiac medications. All patients were on stable cardiac medications for at least six months prior to surgery. Atrial appendage specimens were collected at the time of cardiac surgery and were processed within 1 h of harvest. After one week, CSCs were harvested from the spontaneous outgrowth of plated tissue and used directly for experimentation.

3.2. CSC expression of adhesion molecules

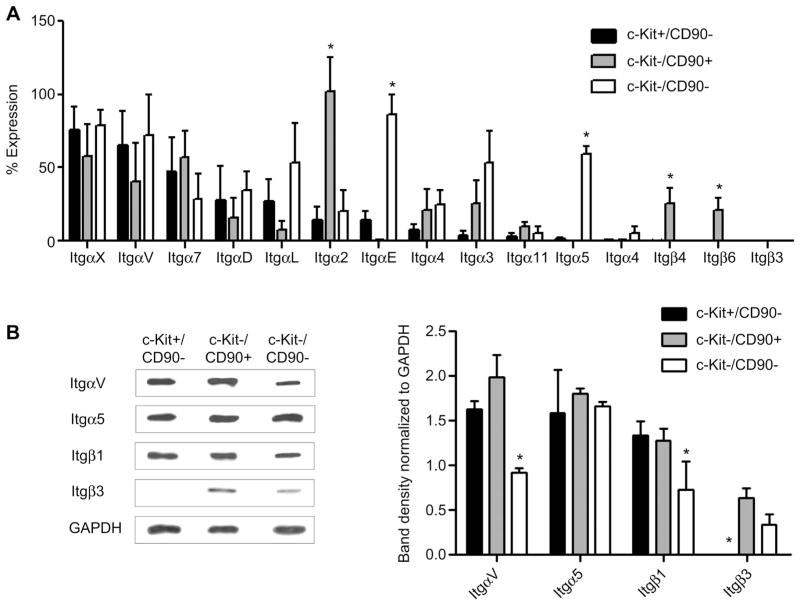

To identify the optimal ECM milieu for CSC proliferation and survival, the integrin expression profile of CSCs was profiled using quantitative PCR. Flow separation of the various sub-populations within CSCs permitted the direct comparison of cardiac progenitor cells (c-Kit+) with mesenchymal progenitor cells (CD90+). Profiling demonstrated that 13 integrin subunits α2-7, α11, αD, αE, αL, αV, αX and β1-8 were variably expressed within CSCs in culture (Fig. 1A). Amongst the 25 integrins profiled, none were differentially expressed by c-Kit+ cells alone while 5 subunits (αM, β2, β3, β7 and β8) were below qPCR detection. The CD90+ sub-fraction demonstrated strong expression of the α2, β1and β6 subunits (p ≤ 0.05 vs. c-Kit+ or c-Kit-/CD90- cells) while β3, β4 and β7 were not detected. The c-Kit-/CD90- subpopulation was distinguished by strong expression of αE and α5 (p ≤ 0.05 vs. c-Kit+ or CD90+ cells) while the β7 and β8 sub-units were not detected. This data demonstrates that while CSCs are spontaneously migrating in culture from the plated tissue biopsy important pro-survival integrins are selectively up-regulated within the sub-populations that comprise CSCs with discreet integrins that define the c-Kit- sub-fractions but not c-Kit+ cells.

Fig. 1.

Surface expression of CSCs integrin. (A): qPCR analysis of integrin expression on relevant sub-populations within the CSC admixture. Data is presented as the percent of total gene expression of CSC integrins normalized to Gapdh; n = 3. (B): Western Blot analysis with corresponding densitometry graph; n = 3.

Given that dimerization between alpha and beta subunits is required for integrin binding to ECM, we profiled the expression of operative integrin proteins that would maintain CSC survival signaling [13,14]. We identified two such integrin dimers are αVβ3 and α5β1, binding partners to fibronectin and fibrinogen–proteins that mediate cell growth and migration [18–20]. These four subunits are present on the surface of the CSCs and rationalize the use of fibronectin and fibrinogen as ideal candidates to customize the hydrogel capsule to support CSCs (Fig. 1B) [21].

3.3. Assessment of CSC viability in capsules

CSCs were encapsulated within low-melt agarose through drop-wise addition to agitate dimethylpolysiloxane prior to rapid cooling and filtration through a 100 μm filter (Fig. 2A). Flow cytometry confirmed that single cell capsules were smaller in size (decreased time of fiight and decreased forward scatter) compared to capsules containing multiple cells (Fig. 2C). ECM proteins were added in the initial agarose/CSC slurry and were efficiently incorporated into the cocoon (Fig. 2D).

The effects of single cell encapsulation on CSC viability were explored by contrasting the proliferation and survival of CSCs in culture after encapsulation with standard adherent and suspended (Poly-HEMA) culture conditions. To provide ECM signals, matrigel capsules were supplemented with both fibrinogen (0.15 mg/mL) and fibronectin (0.25 mg/mL). Using a colorimetric dehydrogenase activity assay, cell viability was assessed 16 h after plating and compared to readings performed at 48 h. Encapsulation significantly improved the viability of CSCs at baseline (0.5 ± 0.06 vs. 0.2 ± 0.05, respectively; p = 0.04) and after 48 h (0.7 ± 0.05 vs. 0.2 ± 0.06; p = 0.002) (Fig. 2E). When accounting for the differences in cell retrieval, CSCs cultured in adherent conditions or matrix supplemented capsules proliferated to an equivalent degree (1.3 ± 0.1 vs.1.4 ± 0.1 fold increase over 24 h; p = 0.7) whereas CSCs cultured in suspended conditions or unsupplemented capsules declined 0.96 ± 0.07 and 0.91 ± 0.06 fold over 24 h (p < 0.05 vs. adherent or matrix supplemented capsules) (Fig. 2E). A trypan blue stain indicated a 19.9% increase in cell death in the suspended culture vs. the normal adherent after 48 h (p = 0.001, data not shown).

The attachment of extracellular matrix to cell integrins is vital to maintain CSC proliferation and viability. The ability of cell encapsulation to mimic adherent cell culture was assessed by comparing the expression of downstream transcripts within the AKT, ERK and JNK pathways in CSCs cultured under adherent, encapsulated and suspended conditions. Expression of Jun, Fos and Bcl-2 was similar in CSCs cultured for 48 h under adherent and encapsulated conditions (p > 0.2; Fig. 2F). CSC culture under suspended conditions uniformly increased the expression of Jun, Fos and Bcl-2 reflecting the apoptotic stresses applied to the cells with loss of vital integrin-dependent attachments to the ECM (p = 0.01, p = 0.04, p = 0.03 vs. adherent, respectively; and p = 0.04, p = 0.05, p = 0.09 vs. encapsulated culture conditions, respectively).

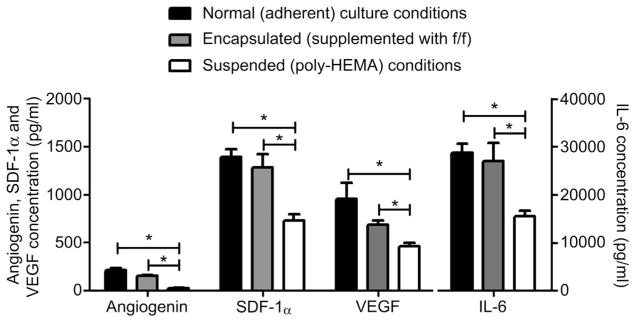

3.4. Paracrine profile analysis of encapsulated CSCs

While direct differentiation into working heart tissue provides a small portion of CSC-mediated benefits, emerging evidence suggests that the local production of cardio-protective and pro-angiogenic cytokines plays an important role in the transplant associated outcomes [6,22,23]. To ensure that the production of cytokines was not inhibited in encapsulated CSCs, a representative panel of cytokines was profiled within conditioned media collected under stress conditions (1% oxygen tension and low serum media) from adherent, encapsulated and suspended CSCs. The angiogenin, SDF-1, VEGF and IL-6 content within conditioned media was maintained in adherent and encapsulated culture conditions (p = 0.3, p = 0.7, p = 0.4, p = 0.6, respectively; Fig. 3). Suspension culture resulted in a uniform decrease in the cytokine content of conditioned media (p = 7E-04, p = 6E-04, p = 1E-04, p = 8E-07 vs. adherent and p = 5E-07, p = 0.02, p = 0.04, p = 0.004 vs. encapsulated culture conditions, respectively).

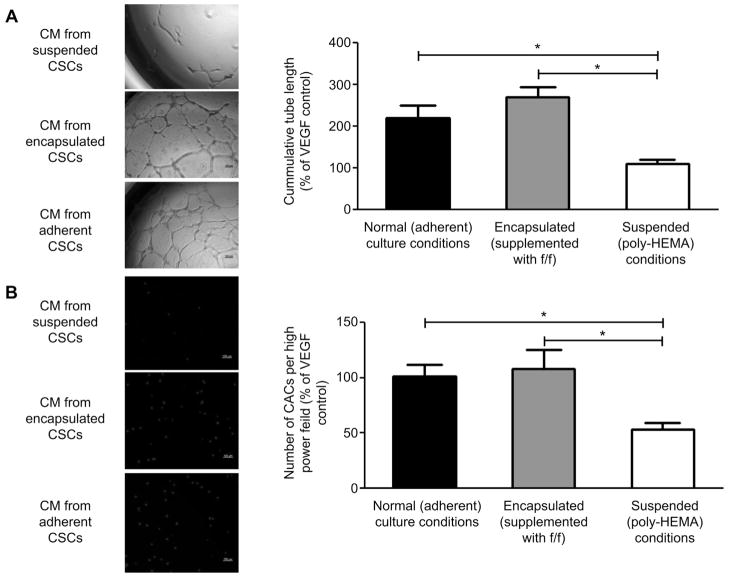

Fig. 3.

ELISA analysis of conditioned media from adherent encapsulated and suspended CSCs culture for 48 h in hypoxic serum restricted conditions.

The effect of CSC encapsulation upon vascular repair was assessed by comparing the ability of conditioned media from adherent, encapsulated and suspended CSCs to promote vascular networks in culture (Fig. 4A). To ensure results were represented on a cell-per-cell basis, all results using the CM from the suspended cell culture were normalized by 19.9% to account for cell death over 48 h as indicated by trypan blue staining. The tubule lengths of HUVECs exposed to conditioned media from encapsulated CSCs were equivalent to tubule lengths cultured in media conditioned from standard adherent culture conditions (286 ± 26% vs. 220 ± 31% of VEGF control tubule formation, p = 0.2). In contrast, the HUVEC tubule length of both adherent and encapsulated conditioned media was significantly longer than media conditioned under suspended culture conditions (112 ± 12%, p = 0.005 and p = 2E-05 respectively).

Fig. 4.

Angiogenesis and migration assays performed on CSC conditioned media. (A): Representative images of matrigel plated HUVECs after 18 h of culture in conditioned media from adherent, encapsulated and suspended CSCs (left) and quantified tubule lengths (right, n = 3). (B): Representative images of migrated CACs through the transwell membrane (left) and quantified number of migrated cells (right, n = 3).

The ability to attract circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) was compared in the conditioned media from adherent, encapsulated and suspended CSCs (Fig. 4B). The number of CACs attracted was maintained by the adherent and encapsulated conditioned media (100 ± 11% vs. 108 ± 17% of positive control; p = 0.7). Fewer CACs were attracted by the conditioned media from suspended cells (53 ± 6%, p = 0.002 and p = 0.009, respectively).

3.5. Effects of capsule components on CSC migration

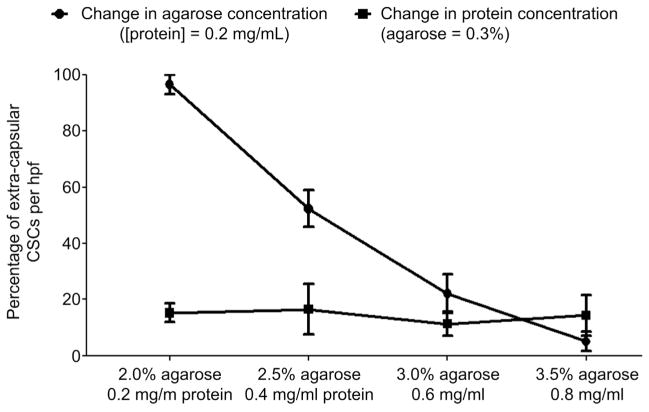

Given that the biophysical properties of the capsule may alter the capacity of CSCs to emerge from injected capsules, we examined the influence of variable capsular ECM protein and matrigel content on the capacity of CSCs to spontaneously migrate from the capsule after 48 h in culture (Fig. 5). Alterations in the capsule ECM content did not influence the ability of CSCs to emerge from the capsules (p = 0.6). Under fixed protein conditions, reducing the matrigel content promoted the spontaneous migration of CSCs from the capsule to cover the culture area (p ≤ 2E-04 between all groups). This in vitro data confirms the notion that increasing the rigidity of the capsule limits the spontaneous migration of CSCs may influence the kinetics of CSC delivery to the myocardium after intra-myocardial injection.

Fig. 5.

Spontaneous migration of CSCs out of the capsule. Random field analysis demonstrating the effects of variable capsular matrigel and protein content on extra-capsular CSC migration after 24 h of culture (n = 3).

3.6. Effects of encapsulation on CSC engraftment and myocardial repair

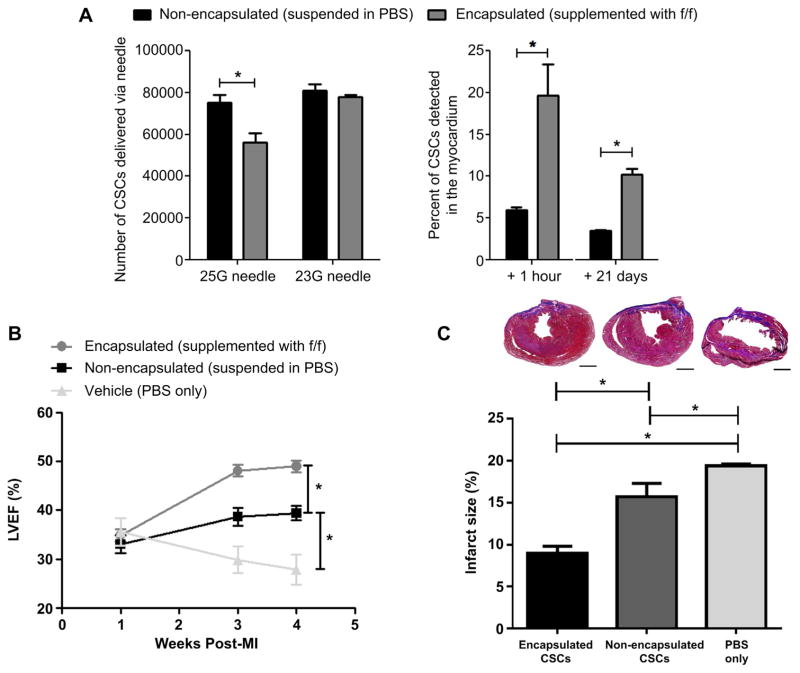

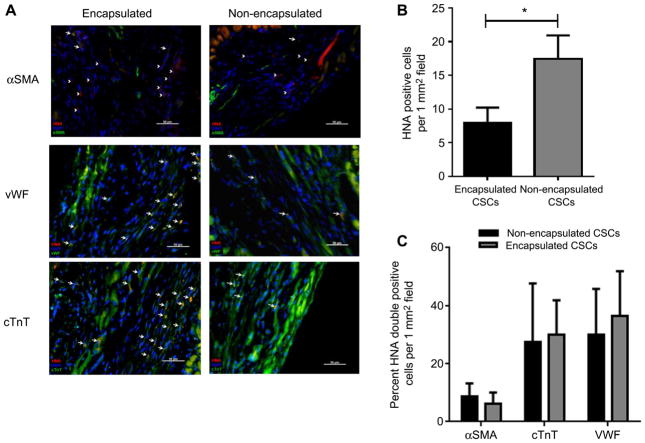

The effect of CSC encapsulation on cell engraftment was compared to isovolume CSC vehicle (PBS) suspensions (Fig. 6). Administration of encapsulated CSCs required the use of 23G needles as the added encapsulation bulk reduced product delivery. Intra-myocardial injection of encapsulated CSCs into immunodeficient mice 1 week after experimental myocardial provided a 3 ± 1 fold enhanced acute retention when compared to delivery of non-encapsulated CSCs (20 ± 4% vs. 6 ± 1% CSCs retained after delivery from the 23G needle, respectively; p = 0.006). Although encapsulation did not completely eliminate ongoing cell loss, long-term retention and survival was greatest in animals treated with encapsulated CSCs as compared to the non-encapsulated CSCs (10 ± 1% vs. 4 ± 1% CSCs retained after 3 weeks, respectively; p ≤ 0.03). Long-term engraftment was confirmed by screening histological sections for the presence of HNA (Fig. 7A, B). HNA positive cells were typically found in the peri-infarct and infarct region of animals. Treatment of animals with encapsulated CSCs provided a two-fold increase in the number of engrafted human CSCs as compared transplant of non-encapsulated CSCs (17.4 ± 3 vs. 7.8 ± 2 HNA+ cells per 1 mm2 random field, respectively; p = 3E-06). Co-localization of HNA+ cells with markers of cardiac identity (α-SMA, cTnT and vWF) demonstrated that encapsulation of CSCs did not influence the fate of injected CSCs (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 6.

Cell retention and post-ischemic cardiac function. (A): qPCR analysis of the number of non-encapsulated cells in standard vehicle or encapsulated cells delivered from a 23G and 25G needle (n = 3/group) and percent of delivered cells detected 1 h (n = 3/group) and 21 days (n = 4/group) after injection into the ischemic myocardium of a SCID mouse. (B): left ventricular ejection fraction measurements of SCID mice injected with standard vehicle only (n = 4), non-encapsulated cells in standard vehicle (n = 7) or encapsulated cells in standard vehicle (n = 7) at week 1, 3 and 4 week post-myocardial infarction. (C): Masson’s trichrome staining and infarct size quantification in SCID mice injected with standard vehicle only (n = 3), non-encapsulated cells in standard vehicle (n = 3) or encapsulated cells in standard vehicle (n = 3) at 3 weeks post-injection. Scale bar = 1000 μm.

Fig. 7.

Staining for human nuclear antigen (HNA) and cardiac lineage markers α-SMA, cTnT and vWF. (A): Random field fluorescent microscopy images (40× magnification). Arrow represents double positive cell, arrow head represents HNA+ cell. (B): Number of HNA+ cells located per random field (1 mm2 section) in animals injected with non-encapsulated cells (n = 3) vs. encapsulated cells (n = 4). (C): Percent of HNA + + cells also expressing markers of cardiac lineage in animals injected with non-encapsulated cells (n = 3) vs. encapsulated cells (n = 4).

Echocardiography (+2 and +3 weeks post-transplant) was used to examine the effects of encapsulation on CSC-mediated cardiac repair (Fig. 6). Baseline LVEF one week after experimental myocardial infarction were similar in the vehicle, non-encapsulated and encapsulated treated animals (36 ± 3 vs. 35 ± 1 vs. 33 ± 2%, respectively; p = 0.9); suggesting similar infarct sizes in all animals. Progressive post-infarct remodeling resulted in a gradual decline in LVEF within the group of control animals treated with vehicle (PBS) only (final LVEF 28 ± 3%; p = 0.05 vs. baseline). Three weeks after delivery of non-encapsulated CSCs, transplant recipients demonstrated a 6 ± 1% (p = 0.02) and 11 ± 3% (p = 0.005) increase in LVEF when compared to baseline or vehicle treatment, respectively. Intra-myocardial injection of encapsulated CSCs enhanced the LVEF three weeks after transplant by 15 ± 2% (p = 7E-05), 10 ± 2% (p = 1E-04) and 22 ± 3% (p = 6E-04) when compared to baseline, transplant of non-encapsulated CSCs and vehicle treatment, respectively. Infarct size measurements from Masson’s trichrome sections demonstrated that treatment with encapsulated CSCs significantly reduced the final scar burden as compared to animals treated with non-encapsulated CSCs or PBS only (9.0 ± 0.8 vs. 15.5 ± 1.6 or 19.4 ± 0.2% scarring of the left ventricle 4 weeks LAD ligation; p = 2E-04 and 4E-06, respectfully).

Taken together, this data suggests that encapsulation boosts the acute retention of CSCs, while a larger initial population and prevention of post-transplant anoikis provides greater long-term retention and CSC-mediated post-infarct cardiac repair.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigate the effect of cocooning CSCs in a hydrogel microcapsule supplemented with integrin-binding proteins on cardiac recovery after myocardial infarction. We demonstrate that encapsulation of CSCs improves cell viability and proliferation; indicating that capsules supplemented with key ECM binding proteins re-establish vital cell-matrix attachments lost during mobilization for transplant. Restoring cell-ECM attachments maintain pro-survival signaling to militate against anoikis and preserve the paracrine signature of CSCs that promote the indirect cardiac repair (i.e., formation of new blood vessels and recruitment of circulating angiogenic cells) that underlies the bulk of CSC-mediated benefits. Upon injection into the border zone of ischemic myocardium, encapsulation promoted engraftment, long-term retention and significantly boosted the degree of cardiac repair observed after CSC treatment.

Remarkable progress has been made towards the design of biomaterials that promote tissue repair and regeneration [5,7]. In recent years, it has become possible to design smart, multi-functional structures that provide bioactive signaling factors that interact with the surrounding tissue environment to facilitate tissue repair and salvage [8,24]. Combining bioactive materials with stem cell products represents a natural extension of these approaches given recent meta-analyses demonstrating only modest persistence of injected stem cell products alone (approx. 1–2%) beyond 12 months [5,12,25,26]. As such, a variety of biomaterials have entered active development with the intent of providing a supportive scaffold that improves both acute cell retention and long-term cell viability [8,13,27].

As compared to similar strategies developed to boost retention of CSCs, cell encapsulation is an attractive candidate for clinical translation given the use of simple general public license-compatible materials (i.e., human fibrinogen/fibronectin and inert matrigel) that permits the ready exchange of nutrients and waste while providing the necessary pro-survival attachment signals. When compared to other biomaterial-based approaches, cell encapsulation avoids delivery of exogenous pro-thrombotic materials (e.g., delivery of excess exogenous collagen [8] or fibrin glue plugging of the injection site) [5], intrinsic modification of the CSCs (e.g., magnet-based retention of iron labeled CSCs) [7,28] or intra-coronary implant of pro-thrombotic metal stents [29]. Importantly, cell encapsulation restricts the use of foreign materials resulting in a significantly lower biomaterial to cell ratio that is gelled prior to transplantation and remains gelled at physiological temperature for straightforward clearance following the integration of CSCs into the myocardium.

Although encapsulation significantly preserved LV function when administered soon after myocardial infarction, progressive loss of transplanted cells still occurs and likely reflects: 1) ongoing clearance via lymphatic or mechanical extrusion, 2) the reduced intra-capsular oxygen tension after transplantation into the ischemic border zone, 3) CSCs damaged during or prior to transplant, and 4) the harsh conditions into which the CSCs encounter after migration out of the capsule. Mechanistically, this improvement is likely in part mediated by the increase of pro-angiogenic and cardioprotective cytokines being released in the post-transplant period due to improved acute retention. However direct differentiation of engrafted CSCs also plays an important role as demonstrated by the greater amount of engrafted working myocardium in animals treated with encapsulated CSCs. But the obvious on-going cell loss provides support for the notion that additional buffers against apoptosis or necrosis will be needed to fully exploit the advantages conferred by enhanced acute retention of CSCs. Future methods to be explored include: 1) enhanced customization of intra-capsular ECM constituents to promote CSC proliferation, 2) impregnation of capsules with supportive cytokines to pre-condition CSCs for survival and to promote indirect cardiac repair, 3) delayed delivery of encapsulated CSCs to permit the establishment of integrin-ECM attachments and survival cell signaling.

Finally, the CSC encapsulation method has some important limitations. Although the process is rapid and uncomplicated, ongoing cell loss occurs during encapsulation as one attempts to regulate capsule size. As a result, the final cell product yield approximates 20% of the initial starting product. Using a microfluidics approach would be beneficial as single cells are successively surrounded by the desired hydrogel/protein mixture, leading to a reproducible final cell product yield near 100%. Furthermore, we anticipate that microcapsule design may benefit from further engineering to improve the acute retention of injected cells. Further enhancements include the addition of extra-capsular proteins (such as proteoglycans) to aid in capsular binding to the host ECM, or cross-linking proteins (such as transglutaminase) to covalently fix capsules to the host ECM proteins.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrate that encapsulation within matrix-supplemented hydrogel capsules improves CSC viability, proliferation and maintains pro-survival pathways through the reintroduction of important cell-matrix attachments. When compared to cells in suspension, encapsulated CSCs have superior secretion of cardio-protective and pro-angiogenic cytokines, which translated to enhanced blood vessel formation and circulating progenitor cell attraction in vitro. In an in vivo model of myocardial infarction, we demonstrate that CSC encapsulation boosts the acute engraftment and long-term survival after injection, translating to enhanced cardiac function compared to non-encapsulated CSCs. In conclusion, CSC encapsulation provides an easy, fast and non-toxic way to treat the cells prior to injection through a clinically acceptable means.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Bin Ye, Ms. Isabelle Gilbert and Dr. Catherine Cheng for assistance with developing the encapsulation protocol. We also thank Mr. Rick Seymour for his help with animal surgery. D.D. is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinician Scientist Award (Phase 2). This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Operating Grant 229694).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

D.J.S. and D.C. are named inventors on a patent application detailing the technology described in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LE, Berman D, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): a prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D’Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, et al. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9806):1847–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4.Bonios M, Terrovitis J, Chang CY, Engles JM, Higuchi T, Lautamaki R, et al. Myocardial substrate and route of administration determine acute cardiac retention and lung bio-distribution of cardiosphere-derived cells. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18(3):443–50. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9369-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terrovitis J, Lautamaki R, Bonios M, Fox J, Engles JM, Yu J, et al. Noninvasive quantification and optimization of acute cell retention by in vivo positron emission tomography after intramyocardial cardiac-derived stem cell delivery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(17):1619–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Narsinh KH, Lan F, Wang L, Nguyen PK, Hu S, et al. Early stem cell engraftment predicts late cardiac functional recovery: preclinical insights from molecular imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:481–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.969329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng K, Li TS, Malliaras K, Davis DR, Zhang Y, Marban E. Magnetic targeting enhances engraftment and functional benefit of iron-labeled cardiosphere-derived cells in myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;106(10):1570–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng K, Blusztajn A, Shen D, Li TS, Sun B, Galang G, et al. Functional performance of human cardiosphere-derived cells delivered in an in situ polymerizable hyaluronan-gelatin hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2012;33(21):5317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng K, Malliaras K, Shen D, Tseliou E, Ionta V, Smith J, et al. Intra-myocardial injection of platelet gel promotes endogenous repair and augments cardiac function in rats with myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(3):256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng K, Shen D, Xie Y, Cingolani E, Malliaras K, Marban E. Brief report: mechanism of extravasation of infused stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(12):2835–42. doi: 10.1002/stem.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terrovitis JV, Smith RR, Marban E. Assessment and optimization of cell engraftment after transplantation into the heart. Circ Res. 2010;106(3):479–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinecke H, Murry CE. Taking the death toll after cardiomyocyte grafting: a reminder of the importance of quantitative biology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(3):251–3. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karoubi G, Ormiston ML, Stewart DJ, Courtman DW. Single-cell hydrogel encapsulation for enhanced survival of human marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5445–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossmann J. Molecular mechanisms of “detachment-induced apoptosis– anoikis”. Apoptosis. 2002;7(3):247–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1015312119693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis DR, Kizana E, Terrovitis J, Barth AS, Zhang Y, Smith RR, et al. Isolation and expansion of functionally-competent cardiac progenitor cells directly from heart biopsies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49(2):312–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruel M, Suuronen EJ, Song J, Kapila V, Gunning D, Waghray G, et al. Effects of off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting on function and viability of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(3):633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pankov R, Yamada KM. Fibronectin at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 20):3861–3. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowlton AA, Connelly CM, Romo GM, Mamuya W, Apstein CS, Brecher P. Rapid expression of fibronectin in the rabbit heart after myocardial infarction with and without reperfusion. J Clin Invest. 1992;89(4):1060–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI115685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takagi J, Strokovich K, Springer TA, Walz T. Structure of integrin alpha5beta1 in complex with fibronectin. EMBO J. 2003;22(18):4607–15. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstandin MH, Toko H, Gastelum GM, Quijada P, De La Torre A, Quintana M, et al. Fibronectin is essential for reparative cardiac progenitor cell response after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2013;113(2):115–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis DR, Ruckdeschel SR, Marban E. Human cardiospheres are a source of stem cells with cardiomyogenic potential. Stem Cells. 2010;28(5):903–4. doi: 10.1002/stem.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chimenti I, Smith RR, Li TS, Gerstenblith G, Messina E, Giacomello A, et al. Relative roles of direct regeneration versus paracrine effects of human cardiosphere-derived cells transplanted into infarcted mice. Circ Res. 2010;106(5):971–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng K, Shen D, Smith J, Galang G, Sun B, Zhang J, et al. Transplantation of platelet gel spiked with cardiosphere-derived cells boosts structural and functional benefits relative to gel transplantation alone in rats with myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2012;33(10):2872–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeevanantham V, Butler M, Saad A, Abdel-Latif A, Zuba-Surma EK, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow cell therapy improves survival and induces long-term improvement in cardiac parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;126(5):551–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delewi R, Andriessen A, Tijssen JG, Zijlstra F, Piek JJ, Hirsch A. Impact of intracoronary cell therapy on left ventricular function in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled clinical trials. Heart. 2013;99(4):225–32. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J, Du KT, Fang Q, Gu Y, Mihardja SS, Sievers RE, et al. The use of human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in RGD modified alginate microspheres in the repair of myocardial infarction in the rat. Biomaterials. 2010;31(27):7012–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng K, Malliaras K, Li TS, Sun B, Houde C, Galang G, et al. Magnetic enhancement of cell retention, engraftment, and functional benefit after intracoronary delivery of cardiac-derived stem cells in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(6):1121–35. doi: 10.3727/096368911X627381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klomp M, Beijk MA, de Winter RJ. Genous endothelial progenitor cell-capturing stent system: a novel stent technology. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6(4):365–75. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.