Abstract

We establish the first transcription-based binary gene expression system in C. elegans using the recently developed Q system. This system, derived from genes in Neurospora crassa, uses the transcriptional activator QF to induce the expression of target genes. Activation can be efficiently suppressed by the transcriptional repressor QS, and suppression in turn can be relieved by the non-toxic small molecule, quinic acid (QA). We used QF/QS and QA to achieve temporal and spatial control of transgene expression in various tissues in C. elegans. We further developed a Split Q system, in which we separated QF into two parts encoding its DNA-binding and transcription-activation domains. Each domain shows negligible transcriptional activity when expressed alone, but co-expression reconstitutes QF activity, providing additional combinatorial power to control gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

The capability to regulate the expression of engineered transgenes has revolutionized the study of biology in multicellular genetic model organisms. One popular and powerful strategy is using a binary expression system such as the tetracycline-regulated tTA/TRE system in mammals1 and the GAL4/UAS/GAL80 system in Drosophila2, 3. Despite its success in Drosophila, so far there is no transcription-based binary expression system reported in the nematode C. elegans.

An alternative method in C. elegans is to use DNA recombinase systems such as FLP/FRT4 or Cre/LoxP5 to remove regulatory elements in transgene constructs to control gene expression. However, the action of the recombinases is not reversible or repressible, and the expression pattern integrates the developmental history of the promoter that drives recombinase expression. Another strategy is to combine heat-shock control and a tissue-specific promoter; in an hsf-1 mutant background that is defective for the heat-shock response, the combination of cell autonomous rescue of hsf-1 and a heat-shock promoter-driven transgene can achieve spatial and temporal control of gene expression6. While this method has many advantages, it requires the transgenes to be expressed in the hsf-1 mutant background. In addition, because worms cannot tolerate extended heat-shock, this method can only achieve gene expression with transient onset and offset.

Recently, a repressible binary expression system, the Q system, was established in Drosophila and mammalian cells based on regulatory genes from the Neurospora crassa qa gene cluster7. The transcriptional activator QF binds to a 16 bp sequence (named QUAS hereafter) and activates expression of target genes under the control of QUAS sites. Expression can be efficiently suppressed by its transcriptional repressor QS and the transcriptional suppression in turn can be relieved by feeding animals quinic acid, a non-toxic small molecule (Fig. 1a). Here we adapted the Q system to the nematode C. elegans, and demonstrated its utility for controlling transgene expression with temporal and spatial precision. We also developed the “Split Q system” by separating the transcriptional activator QF into two parts, to achieve intersectional control of gene expression.

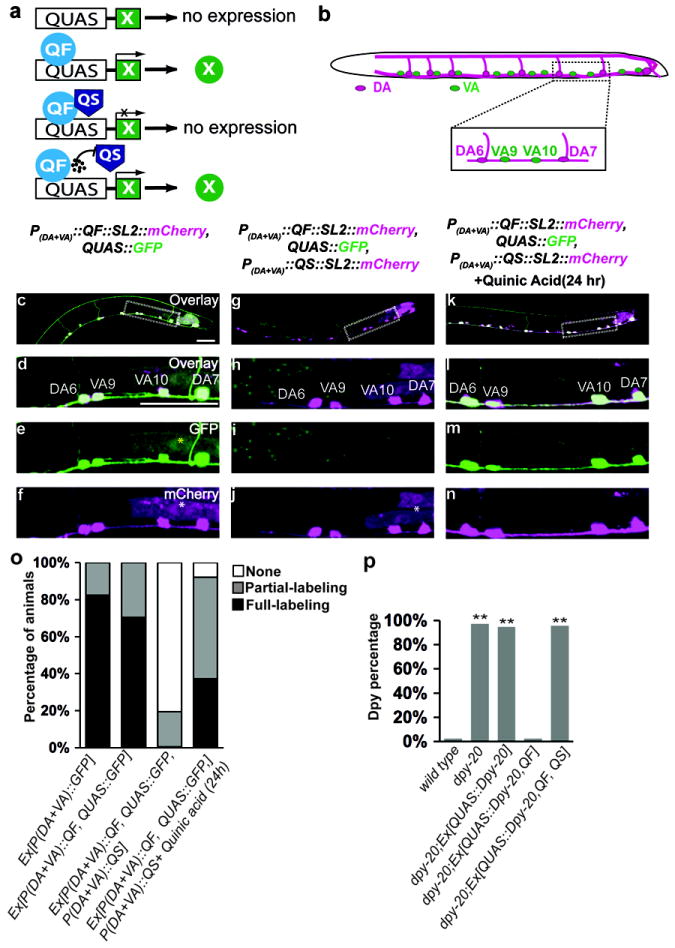

Fig. 1. The repressible Q binary system functions effectively in C. elegans.

(a) Schematic of the Q system. X indicates transgene. Black circles at the bottom indicate quinic acid.

(b) Schematic diagram of VA and DA motor neurons in the ventral nerve cord (VNC). The boxed region is magnified to show VA9 and VA10 neurons in green and DA6 and DA7 in magenta. (c-n) The micrographs show transgenic worms (L3 larvae) expressing the indicated transgenes, with or without treatment with quinic acid for 24h. An overview of the VNC (c, g, k) and magnification of the boxed region (d-n) are shown. GFP expression is shown green, mCherry expression is shown in magenta. P, promoter; SL2, trans-spliced leader sequence. White asterisks denote ectopic gut fluorescence caused by SL2∷mCherry cassette (X. Wei and K. Shen, unpublished results). Yellow asterisks denote occasional ectopic gut fluorescence due to QUAS∷GFP. Scale bars, 20 μm. (o) Quantification of labeling efficiency in (c-n). Late L3 or early L4 stage larvae were scored (n>200 for each strain). Animals are divided into 3 categories: None (no A-type neurons labeled), Full-labeling (all A-type neurons labeled) and Partial-labeling (between None and Full-labeling). (p) Quantification of Dpy rescue efficiency with Q system in Supplementary Figure 4. n =40 for each group; **P ≤0.0001 (versus wild type animals), χ2 test. Animals with a body length longer than 972 μm are scored as wild type. Animals with a body length shorter than 972 μm are scored as Dpy mutants.

RESULTS

Characterization of the Q system in C. elegans

We used the Q system to label A-type motor neurons in C. elegans. A-type motor neurons (DAs and VAs) are cholinergic, excitatory and responsible for backward movement8. The cell bodies of both DAs and VAs are located in the ventral nerve cord, and DA neurons send their axonal commissures to the dorsal nerve cord, while VA neurons extend their axons exclusively in the ventral nerve cord (Fig. 1b). We used the unc-4 promoter (expressed in both DA and VA neurons)9 to drive the expression of QF and monitored expression of QF with a SL2∷mCherry cassette. The trans-spliced leader sequence SL2 permits the bicistronic expression of QF and mCherry under the control of the unc-4 promoter in a manner similar to the Internal Ribosomal Entry Site (IRES) in the vertebrate system10.

The transcriptional machinery of C. elegans requires a minimal promoter to initiate transcription. After trying several such sequences (data not shown), we found that the Δpes-10 minimal promoter11 supports strong expression with the Q system in C. elegans. We created a transgenic strain (wyEx3661) that co-express the QF construct together with the QUAS∷Δpes-10∷GFP (shortened as QUAS∷GFP hereafter) construct. As expected, GFP was robustly expressed in DA and VA neurons in co-expressing lines (Fig. 1c-1f) but not in lines expressing the constructs individually (Supplementary Figure 1a-1d). The fraction of animals showing expression with the QF system is comparable to that seen with direct promoter fusion (Fig. 1o). When the two single-expressing transgenic strains were crossed together, we also obtained robust GFP expression in both DAs and VAs in animals bearing both transgenes (Supplementary Figure 1e-1f), excluding the possibility that GFP fluorescence is due to recombination between the unc-4 promoter and QUAS∷GFP during the generation of the extrachromosomal array12.

To test whether the action of QF is repressible, we generated a transgenic line (wyEx4048) coexpressing QS, QF and QUAS∷GFP in A-type neurons. In these animals, the expression of GFP in DA and VA neurons was efficiently suppressed (Fig. 1g-1j and Fig. 1o). Finally, to test if quinic acid can de-repress the QS inhibition of QF, we applied the drug to the same QS transgenic strain. Transgenic larvae fed on quinic acid showed detectable GFP signal after 6 hr, which increased over time (Supplementary Figure 2) and was saturated after 24 hr of drug application (Fig. 1k-1o). The effective concentration of quinic acid (7.5 mg/ml, similar to the doses used in Drosophila and Neurospora crassa) does not cause noticeable abnormalities of animals (Online Methods), and is lower than the concentration of quinic acid naturally present in cranberry juice (>1%)13. Interestingly, the de-repression effect of quinic acid in C. eleagns is more rapid than in flies7 and may be useful for temporally regulating QF-driven transgene expression.

Application of Q system in various tissues

We expressed QF in body wall muscles of QUAS∷GFP transgenic worms using the myo-3 promoter, and it robustly activated the expression of GFP in this tissue (Supplementary Figure 3a). GFP expression was effectively suppressed by co-expressing QS in body wall muscles and the suppression was relieved when animals were fed with quinic acid (Supplementary Figure 3b,c).

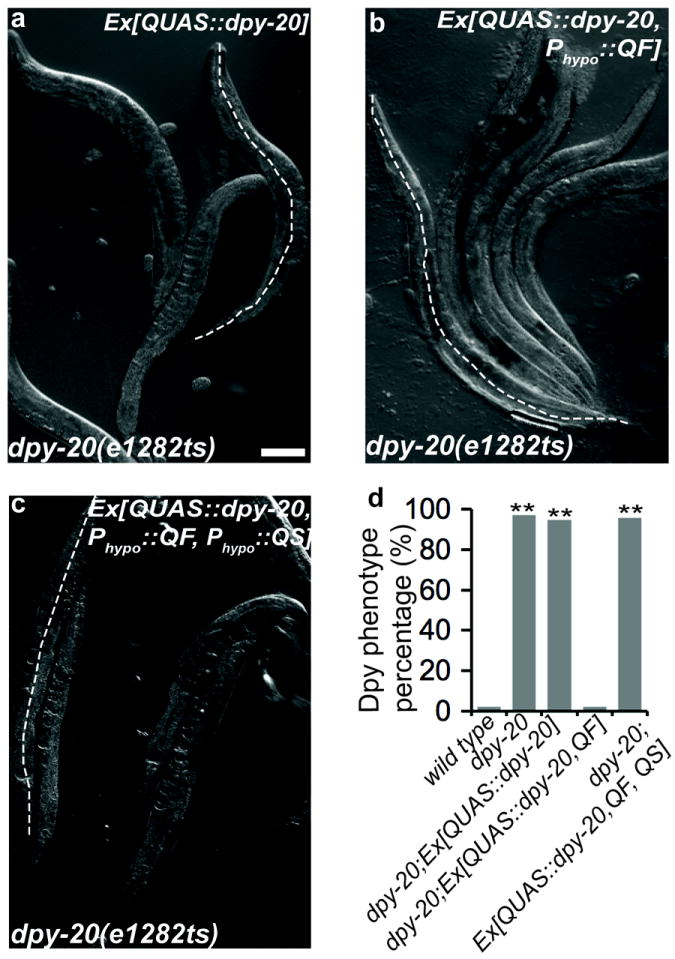

We investigated whether we could use this system to express non-fluorescent transgenes. The dpy-20 gene encodes a nematode specific zinc finger protein, which is expressed and required in hypodermal cells for normal body morphology14. dpy-20 (e1282ts) mutant animals raised at restrictive temperature (25°C) exhibit a Dpy (shortened body length) phenotype (body length: wild-type 1052±40 μm, dpy-20 922±14 μm; n =40)14. dpy-20 (e1282ts) mutants carrying only the QUAS∷dpy-20 transgene still showed the Dpy phenotype (Supplementary Figure 4a; body length: 920±17 μm; n =40), but co-expression of QF in hypodermal cells using dpy-7 promoter rescued the phenotype (Supplementary Figure 4b; body length: 1085±94 μm). Furthermore, rescue was suppressed when QS was expressed in hypodermal cells (Supplementary Figure 4c and Fig. 1p; body length: 917±25 μm) and the suppression was relieved when the animals were allowed to develop in the presence of quinic acid (data not shown).

Refining expression patterns with a NOT gate

In addition to permitting precise spatial and temporal control of transgene expression in various tissues, the Q system can also be utilized to refine spatial control. In C. elegans, while some promoter elements are highly specific for a single cell or few cells, most promoters are expressed in many cells15. It is desirable to develop specific labeling schemes for the reproducible marking of small subsets of cells. The repressible Q system can meet this need by combining QF and QS into a NOT gate. For instance, for A-type motor neurons, DA and VA neurons are both labeled by the unc-4 promoter while a truncated unc-4 promoter (unc-4c) is expressed only in DA neurons in the ventral nerve cord (M. Vanhoven and K. Shen, unpublished results; Supplementary Figure 5). However, there is no available promoter to only label VA neurons (Fig. 2a). To achieve specific expression in VA neurons, we created transgenic strains that coexpress unc-4∷QF (VA + DA neurons), unc-4c∷QS (DA neurons only) and QUAS∷GFP simultaneously. In the same line, we also used a SL2∷mCherry cassette fused with QF and QS to label both the DA and VA neurons. In 96% (98/102) animals of these transgenic stains, we found that GFP could only be detected in the VA neurons, evident from the lack of commissures in the GFP channel, while the mCherry signals could be detected in both VA and DA neurons (Fig. 2b-2d). Therefore, expression of the QS in DA neurons limited activity of QF to only VA neurons.

Fig. 2. Refining expression patterns in VA motor neurons with a NOT gate.

(a) Schematic diagram of VA and DA motor neurons in the posterior region of the VNC. DA neurons extend axonal commissures (magenta arrowheads) to the dorsal nerve cord. The unc-4 promoter is expressed in VA and DA neurons while the unc-4c promoter is only expressed in DA neurons. (b-d) The micrographs show the same region as schematically depicted in (a) in an early L4 larva expressing the indicated transgenes. Magenta shows mCherry expression and green shows GFP expression. White arrowheads indicate the commissures of DA neurons. The asterisk denotes ectopic gut fluorescence caused by SL2∷mCherry cassette. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Refining expression patterns with an AND gate

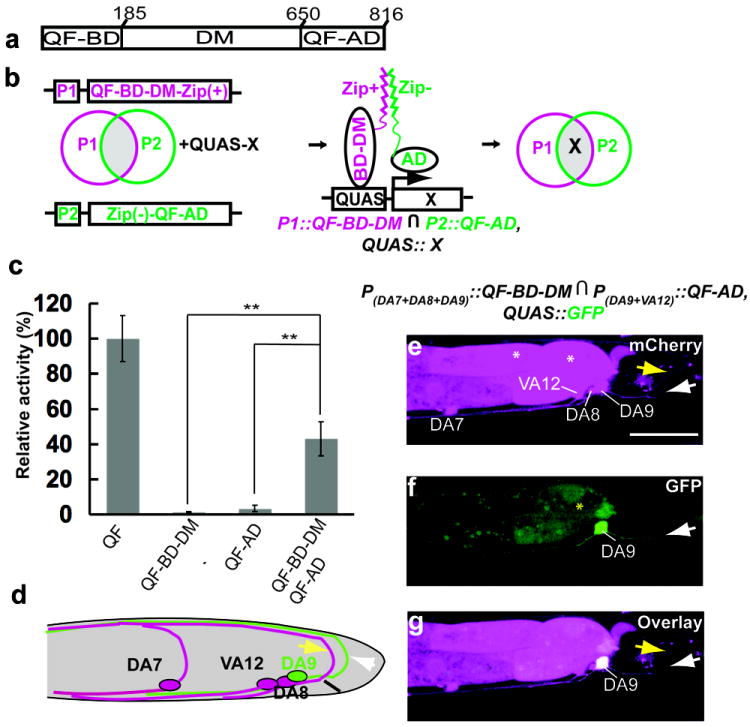

In Drosophila, the DNA binding (BD) and transcription activation (AD) domains from GAL4 can be independently expressed using different promoters, and transcriptional activity can be reconstituted within the intersectional subset of two promoters16. QF has an analogous organization and contains a DNA binding (BD) domain, a putative dimerization (DM) domain and a transcription activation (AD) domain17 (Fig. 3a). We tested whether QF can be similarly divided into two modules that can be used for intersectional labeling (Fig. 3b). We fused a heterodimerizing leucine zipper fragment with each domain to enhance the reconstitution efficiency of active QF18. We found that the putative dimerization domain (DM) is required for reconstituted activity (Supplementary Table 1). The reconstituted activity of the optimal pair is 42% of intact QF driven by the same promoter, measured as the expression level of QUAS∷GFP in these transgenic strains. Transgenic lines only expressing the individual domains of QF displayed minimal transcriptional activity (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. The Split Q system.

(a) Schematic showing the DNA binding domain (QF-BD), the putative dimerization domain (DM) and the transcription activation domain (QF-AD) of QF. The amino acid positions for each domain are indicated. (b) Schematic depiction of the Split Q system. The QF-BD-DM and QF-AD are driven using different promoters (P1 and P2). Zip+ and Zip- are a pair of heterodimerization leucine zippers. The transgene X is expressed only at the intersection of P1 and P2 promoters (gray area). ∩ denotes the intersection of P1 and P2. (c) Relative transcriptional activities (measured as GFP fluorescence intensity) of the indicated Split Q constructs, normalized to the activity measured in strains containing intact QF. All constructs were driven by the same promoter (mig-13). Error bars, S.E.M. **P<0.01, n=40, one-tailed t-test. (d) Schematic diagram of DA and VA neurons in the tail region (left view). The mig-13 promoter is expressed in DA9 and VA12 neurons while the unc-4c promoter is expressed in DA7, DA8 and DA9 neurons. The yellow and white arrows indicate the commissures of DA8 and DA9 respectively. (e-g) The micrographs show an early stage 4 larva expressing the indicated transgenes. Green shows GFP fluorescence, magenta shows mCherry fluorescence. The yellow and white arrows indicate the commissures of DA8 and DA9 respectively. White asterisks denote ectopic gut fluorescence caused by SL2∷mCherry. The yellow asterisk denotes occasional ectopic gut fluorescence due to QUAS∷GFP. Scale bar, 20 μm.

To test whether the Split Q system can be applied to label the intersectional group of two different promoters, we expressed QF-AD from the mig-13 promoter and QF-BD-DM from the unc-4c promoter (wyEx4355). In the tail region, the mig-13 promoter is expressed in DA9 and VA12 neurons19 while the unc-4c promoter is expressed in DA7, DA8 and DA9 neurons (Fig. 3d). All the neurons were labeled by the SL2∷mCherry cassette fused with the two halves of QF. We found that QUAS∷GFP was only expressed in the DA9 neuron (61%, 62/103 in this line), which is at the intersection of the expression patterns of mig-13 and unc-4c promoters (Fig. 3e-3g), and no animals (0/103) show GFP labeling in other tail neurons. Transgenic lines only expressing mig-13∷QF-AD displayed no GFP signal in DA9 (data not shown). Moreover, the reconstituted activity of QF was suppressed completely in 98% of animals (202/207) by co-expressing unc-4c∷QS introduced by sequential injection (wyEx4355;wyEx4409).

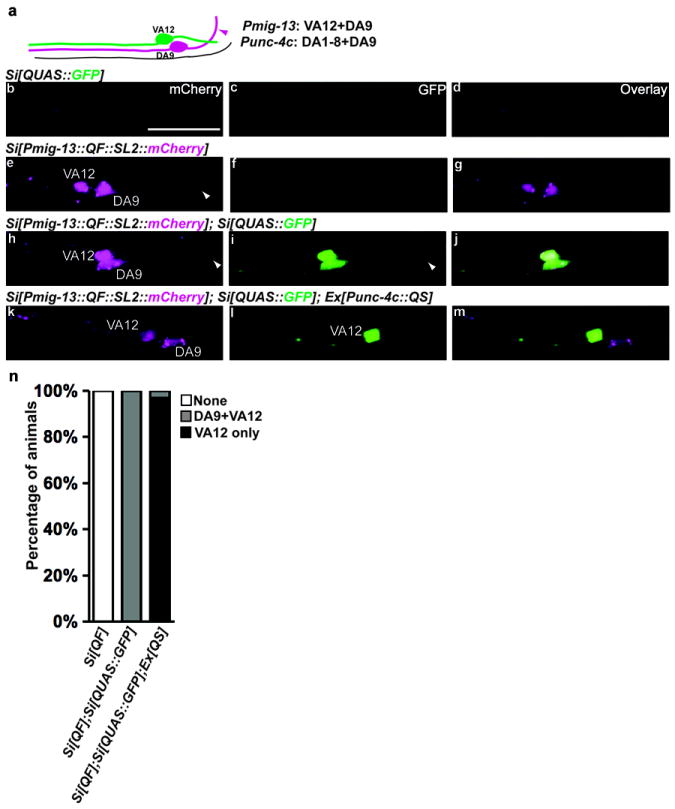

The Q system functions effectively with single copy transgenes

Standard transgenic technique in C. elegans involves microinjection of exogenous DNA into the gonad, which results in complex extrachromosomal arrays containing high copy number transgenes. While this method is convenient and frequently used, it does not provide stable transgenes or reliable expression levels due to silencing effects20. An alternative transgenic method, Mos1 mediated Single Copy Insertion (MosSCI), uses the transposon Mos1 to introduce a single-copy, stably inherited transgene21. We tested whether the Q system was functional when its components were integrated as single copy MosSCI transgenes. We created two MosSCI transgenes that contain QUAS∷GFP(wySi374) and Pmig-13∷QF∷SL2∷mCherry (wySi377), respectively. Neither transgene alone yielded a GFP signal (Fig. 4b-4g and Fig. 4o). However, animals carrying both transgenes consistently showed robust expression of GFP in VA12 and DA9 neurons (100%, 120/120), reflecting the promoter activity of Pmig-13 (Fig. 4h-6j and Fig. 4o). In addition, when QS driven by unc-4c promoter (expressed in all DA neurons including DA9) was introduced into this strain, the transcriptional activation in DA9 neuron was specifically suppressed by QS, leaving VA12 neuron as the only GFP positive neuron in 97% animals (126/130) (Fig. 4k-4o). These results demonstrate that Q system components are functional when expressed from both array transgenes as well as integrated, single-copy transgenes.

Fig. 4. The Q system functions effectively with single copy transgene.

(a) Schematic diagram of DA9 and VA12 neurons in the tail region. The mig-13 promoter expresses in DA9 (in magenta) and VA12 (in green) neurons while the unc-4c promoter expresses in the DA9 neuron. The magenta arrowhead indicates the commissure of DA9. (b-m) The images show the same region as schematically depicted in (a) in transgenic worms (L4 larvae) containing the indicated transgenes. GFP expression is shown green and mCherry expression is shown in magenta. Si, single insertion. The white arrowheads indicate the commissures of DA9. Scale bar, 20 μm. (n) Quantification of labeling efficiency in (b-m). Late L3 or early L4 stage larvae were scored (n>100 for each strain). Animals are divided into 3 categories: None (neither DA9 nor VA12 neurons are labeled by GFP), DA9+VA12 (both neurons are labeled), VA12 only (only VA12 neuron is labeled).

DISCUSSION

Here we show that the Q repressible binary expression system functions efficiently in the nematode C. elegans, similar to its application in the mammalian cells and Drosophila. It enables greatly improved spatial and temporal control of transgene expression in various tissues. Compared to transgene expression driven directly by promoters, the repressible Q binary system offers several advantages. First, it is difficult to “turn off” or “turn down” gene expression by direct promoter fusion methods. In contrast, QS expression provides an efficient approach to suppress gene expression. With the regulatory role of quinic acid, the Q system can “turn on” gene expression at any desired time point, and combines spatial and temporal control. Second, using combination of promoters, the Q system can refine transgene expression to more specific subsets of cells. Third, although it is routine to generate transgenic C. elegans lines with direct promoter-fusion methods, using new promoters or effectors in each case necessitates that the transgenes must be transformed (and possibly integrated) again. By comparison, a library of single copy insertion strains containing transgenes expressing various QF drivers and/or QUAS effectors can be systematically combined by genetic crosses to generate reproducible expression patterns. The Q system could become a significant pillar of the C. elegans toolbox as more and more strains containing QF and QUAS-effector transgenes become available.

Finally, our newly introduced Split Q system affords a higher degree of control and can achieve expression even at single cell resolution. Due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the nervous system, one bottleneck in understanding neural circuits and behavior is genetic access to specific neurons or groups of neurons, such that one can reproducibly label them with anatomical or developmental markers, express genetically-encoded indicators of activity, or selectively silence or activate specific neurons22. The Split Q system should greatly increase the precision of genetic access to specific neuronal populations. This system could also be applied to other model organisms to achieve more precise control of transgene expression.

ONLINE METHODS

Expression constructs

Expression clones were made in the pSM vector, a derivative of pPD49.26 (A. Fire) with extra cloning sites (S. McCarroll and C. I. Bargmann, personal communication). gpd-2 SL2∷mCherry was PCR amplified from pBALU1223 in which the kanamycin cassette and N-terminus nuclear localization sequence (NLS) were removed. The QF was amplified from pCaSpeR4, the QS was amplified from pACPL-QS and 5xQUAS was amplified from pQUAS-CD8-GFP7. Δpes-10 minimal promoter was amplified from pPD97.78 and myo-3 promoter was from pPD122.66 (A. Fire). The unc-4 promoter (4kb)9, the unc-4c promoter (bashed unc-4 promoter, ~1 kb, M. Vanhoven and K. Shen, unpublished results), mig-13 promoter (3.4kb)19 and dpy-7 promoter (218bp)24 were amplified from N2 genomic DNA. The dpy-20 genomic DNA (3kb, including the whole dpy-20 gene from initial ATG to stop codon) was amplified from fosmid WRM0616CH07. QF-AD was the C-terminus part (650-816aa) of QF17, adding GSGSGSGSGSGT linker sequence at 5’ and SV40 NLS at 3’. The sequence of Zip(-) antiparallel leucin zipper (AQLEKKLQALEKKLAQLEWKNQALEKKLAQ) was amplified from CZ-CED-3 (a gift from M. Chalfie)25, and was fused with QF-AD fragment by overlapping PCR, adding NheI sites at 5’ and 3’ends. QF-BD-DM was the N-terminus part (1-650aa) of QF, adding SV40 NLS at 5’ and GSGSGSGSGSGSA linker sequence at 3’. The sequence of Zip(+) antiparallel leucin zipper (ALKKELQANKKELAQLKWELQALKKELAQ) was amplified from CED-3-NZ (a gift from M. Chalfie)25, and was fused with QF-BD-DM fragment by overlapping PCR, adding NheI sites at 5’ and 3’ ends. Details about primer sequences and constructs are available in Supplementary Note 1. All plasmids are available upon request.

Strains and transformation

Wild-type animals were C. elegans Bristol strain N2. All mutants used in the paper were provided by Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. Strains were maintained using standard methods26, and animals were grown at 20°C except lines containing Split Q constructs and dpy-20 (e1282ts), which were grown at 25°C. Normal transgenic lines were made using standard protocols12. Transgenic arrays were generated in N2 background except dpy-20 (e1282ts) used for Dpy rescue experiments. For each transformation, at least two transgenic lines were obtained showing similar results. MosSCI transformation was performed based on the protocol described in http://sites.google.com/site/jorgensenmossci/21. The Mos1 insertion strains EG4322 or EG5003 were used for injection. These single copy insertions were verified by following the protocol of long-fragment PCR provided by Michael Nonet. (http://thalamus.wustl.edu/nonetlab/ResourcesF/PCR%20of%20MosSCI%20transgenes.pdf) Strains information in detail is available in Supplementary Note 2.

Quinic acid de-suppression treatment

The fresh quinic acid stock solution (300 mg/ml) was prepared from D- (–)-quinic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%, Catalog # 138622) in sterile Milli-Q water. The stock can be kept in 4°C for at least one month. Neutralized with 5M NaOH to pH 6-7, the quinic acid stock solution can be added into NGM agar medium (7.5 mg/ml) before pouring into petri plates or onto NGM plates seeded with OP50 directly (per 60 mm × 15 mm petri dish, 40 μl M9 buffer with ~300 μl quinic acid stock solution, adding ~60-70 μl 5M NaOH to pH 6.0-7.5. pH is tested by EMD pH-indicator strips, pH 5.0-10.0, Cat.9588). Animals were synchronized by hypochlorite bleaching and were cultured on NGM plates with OP50. They were transferred onto quinic acid plates with OP50 6 hr, 12 hr, 24 hr or 30 hr before taking images. Animals kept on seeded NGM plates containing quinic acid for five generations exhibited no noticeable abnormalities of morphology, development, brood size, egg-laying behavior, and touch response.

Confocal imaging and image quantification

Images of fluorescent proteins were captured in live animals using Plan-Apochromat 40X/1.3NA objective except Fig. 3e-3g (using Plan-Apochromat 63X/1.4NA objective), and Supplementary Figure 3-4 (Plan-Apochromat 10X/10.47NA objective) on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Animals were immobilized on 2% agarose pad using 10 mM levamisole (Sigma-Aldrich) and oriented anterior to the left and dorsal up. For imaging and measuring body length 0.3 M 2,3-butanedione monoxime (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. Supplementary Figure 3 are overlays of single fluorescent single plane image and DIC image, and Supplementary Figure 4 are DIC images. All images were taken using Zen2009 (Carl Zeiss) and confocal images were rendered in three dimensions by maximum intensity projection method. Images were adjusted as necessary in Photoshop (Adobe) using cropping and thresholding tools, and assembled into figures using Illustrator (Adobe). For quantification of fluorescence intensity in Fig. 3c, fluorescence images of ventral nerve cord neurons labeled by mig-13 promoter (DD and DA neurons) were captured using the same parameters across groups with a 40X objective. The total fluorescence intensity of GFP in each cell body was determined using Image J (NIH) and Excel (Microsoft) by integrating pixel intensity across the cell body region. 40 neurons from 20 early L4 larvae were used to calculate the average fluorescence intensity for each group. The activity was normalized to the percentage of the activity measured in strains containing intact QF (wyEx4212).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1 Both QF and QUAS are required for binary expression.

Supplementary Figure 2 The time course (6 hr and 12 hr) of derepression of QS by quinic acid.

Supplementary Figure 3 Q system functions in C. elegans body wall muscles.

Supplementary Figure 4 Q system for functional rescue in hypodermal cells.

Supplementary Figure 5 The expression pattern of the unc-4c promoter.

Supplementary Figure 6 Vector maps containing components of Q system and Split Q system with available cloning sites.

Supplementary Table 1 Relative transcriptional activities of primary Split Q constructs tested during design optimization.

Supplementary Note 1 Constructs information.

Supplementary Note 2 Strains information.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank Miri Vanhoven for the unc-4c promoter and the transgene wyEx1817, Erik Jorgensen lab for the MosSCI technique and protocol, Michael Nonet for long fragment PCR protocol, Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for providing strains, C. Gao, T. Boshika and Y. Fu for technical assistance, and members of the Shen Lab for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

X.W. and K.S. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. X.W. performed all experiments and data analysis. L.L and C.J.P. provided unpublished information on the Q system and guided experimental design.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight Control of Gene-Expression in Mammalian-Cells by Tetracycline-Responsive Promoters. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted Gene-Expression as a Means of Altering Cell Fates and Generating Dominant Phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee T, Luo LQ. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macosko EZ, et al. A hub-and-spoke circuit drives pheromone attraction and social behaviour in C. elegans. Nature. 2009;458:1171–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature07886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis MW, Morton JJ, Carroll D, Jorgensen EM. Gene activation using FLP recombinase in C. elegans. Plos Genet. 2008;4:e1000028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacaj T, Shaham S. Temporal control of cell-specific transgene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;176:2651–2655. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.074369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter CJ, Tasic B, Russler EV, Liang L, Luo LQ. The Q System: A Repressible Binary System for Transgene Expression, Lineage Tracing, and Mosaic Analysis. Cell. 2010;141:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The Structure of the Nervous-System of the Nematode Caenorhabditis-Elegans. Philos T Roy Soc B. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller DM, Niemeyer CJ. Expression of the Unc-4 Homeoprotein in Caenorhabditis-Elegans Motor-Neurons Specifies Presynaptic Input. Development. 1995;121:2877–2886. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spieth J, Brooke G, Kuersten S, Lea K, Blumenthal T. Operons in C-Elegans - Polycistronic Messenger-Rna Precursors Are Processed by Transsplicing of Sl2 to Downstream Coding Regions. Cell. 1993;73:521–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90139-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seydoux G, Fire A. Soma-Germline Asymmetry in the Distributions of Embryonic Rnas in Caenorhabditis-Elegans. Development. 1994;120:2823–2834. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mello C, Fire A. DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:451–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nollet LML. Food analysis by HPLC. Vol. 100. CRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DV, Suleman DS, Beckenbach KA, Gilchrist EJ, Baillie DL. Molecular cloning and characterization of the dpy-20 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:367–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00293205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Ma C, Chalfie M. Combinatorial marking of cells and organelles with reconstituted fluorescent proteins. Cell. 2004;119:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luan H, Peabody NC, Vinson CR, White BH. Refined spatial manipulation of neuronal function by combinatorial restriction of transgene expression. Neuron. 2006;52:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giles NH, Geever RF, Asch DK, Avalos J, Case ME. The Wilhelmine E. Key 1989 invitational lecture. Organization and regulation of the qa (quinic acid) genes in Neurospora crassa and other fungi. J Hered. 1991;82:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jhered/82.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. Antiparallel leucine zipper-directed protein reassembly: Application to the green fluorescent protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5658–5659. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sym M, Robinson N, Kenyon C. MIG-13 positions migrating cells along the anteroposterior body axis of C. elegans. Cell. 1999;98:25–36. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh J, Fire A. Recognition and silencing of repeated DNA. Annual Review of Genetics. 2000;34:187–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frokjaer-Jensen C, et al. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K. Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron. 2008;57:634–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tursun B, Cochella L, Carrera I, Hobert O. A toolkit and robust pipeline for the generation of fosmid-based reporter genes in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilleard JS, Barry JD, Johnstone IL. cis regulatory requirements for hypodermal cell-specific expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle collagen gene dpy-7. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2301–11. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chelur DS, Chalfie M. Targeted cell killing by reconstituted caspases. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2283–2288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610877104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 Both QF and QUAS are required for binary expression.

Supplementary Figure 2 The time course (6 hr and 12 hr) of derepression of QS by quinic acid.

Supplementary Figure 3 Q system functions in C. elegans body wall muscles.

Supplementary Figure 4 Q system for functional rescue in hypodermal cells.

Supplementary Figure 5 The expression pattern of the unc-4c promoter.

Supplementary Figure 6 Vector maps containing components of Q system and Split Q system with available cloning sites.

Supplementary Table 1 Relative transcriptional activities of primary Split Q constructs tested during design optimization.

Supplementary Note 1 Constructs information.

Supplementary Note 2 Strains information.