Abstract

Magnesium has important structural, catalytic and signaling roles in cells, yet few tools exist to image this metal ion in real time and at subcellular resolution. Here we report the first genetically encoded sensor for Mg2+, MagFRET-1. This sensor is based on the high-affinity Mg2+ binding domain of human centrin 3 (HsCen3), which undergoes a transition from a molten-globular apo form to a compactly-folded Mg2+-bound state. Fusion of Cerulean and Citrine fluorescent domains to the ends of HsCen3, yielded MagFRET-1, which combines a physiologically relevant Mg2+ affinity (K d = 148 µM) with a 50% increase in emission ratio upon Mg2+ binding due to a change in FRET efficiency between Cerulean and Citrine. Mutations in the metal binding sites yielded MagFRET variants whose Mg2+ affinities were attenuated 2- to 100-fold relative to MagFRET-1, thus covering a broad range of Mg2+ concentrations. In situ experiments in HEK293 cells showed that MagFRET-1 can be targeted to the cytosol and the nucleus. Clear responses to changes in extracellular Mg2+ concentration were observed for MagFRET-1-expressing HEK293 cells when they were permeabilized with digitonin, whereas similar changes were not observed for intact cells. Although MagFRET-1 is also sensitive to Ca2+, this affinity is sufficiently attenuated (K d of 10 µM) to make the sensor insensitive to known Ca2+ stimuli in HEK293 cells. While the potential and limitations of the MagFRET sensors for intracellular Mg2+ imaging need to be further established, we expect that these genetically encoded and ratiometric fluorescent Mg2+ sensors could prove very useful in understanding intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis and signaling.

Introduction

Magnesium is the most abundant intracellular divalent cation and is involved in numerous essential cellular processes including replication, transcription, translation and energy metabolism. In addition to its omnipresent role as an essential enzymatic cofactor, Mg2+ is also important for chromatin stability and regulates specific ion channels [1], [2]. The total cellular Mg2+ concentration ranges between 14–20 mM, but the concentration of free Mg2+ in the cytosol has been estimated to be between 0.1 and 1.5 mM [3]–[7]. Given its importance to so many different cellular processes, the intracellular Mg2+ concentration is generally believed to be strongly buffered and tightly regulated by the combined action of magnesium binding (macro)molecules (proteins, ribonucleic acids, ATP, etc.), storage in organelles and the action of Mg2+ channels [8]–[10]. Hereditary disorders related to Mg2+ homeostasis have been shown to result in diminished kidney functioning and in severe cases to renal failure, muscle spasms and seizures [11]. Magnesium deficiency has also been shown to accelerate cellular senescence [12], providing a potential link between low dietary magnesium intake and the early onset of aging diseases such as diabetes [13], cardiovascular diseases [14] and osteoporosis [15]. Recent studies suggested that T cell activation following antigen receptor stimulation was dependent on a transient influx of Mg2+ in the cytosol, implicating a novel role for Mg2+ as second messenger in intracellular signal transduction [16].

Despite the abundance and importance of Mg2+, the intracellular regulation of Mg2+ homeostasis and the putative role of Mg2+ in intracellular signal transduction are not well understood. In part this is because of a lack of convenient molecular tools to image the intracellular Mg2+ concentration in single living cells in real time [17]. Magnesium-selective microelectrodes have been used to determine cytosolic Mg2+ levels in different muscle cells, revealing concentrations between 0.7 and 0.9 mM [4]. However, these microelectrodes are highly invasive and do not provide spatial information. Another method to probe the intracellular concentration of Mg2+ is the measurement of the ratio of Mg2+-bound and Mg2+-free ATP using 31P NMR [18]. While non-invasive, 31P NMR measures Mg2+ indirectly and averaged over a large collection of cells [19], [20]. The currently most commonly applied approach uses synthetic dyes that alter their fluorescent properties upon binding of Mg2+ [21]–[27]. However, many of the available dyes show limited specificity for Mg2+ and often bind Ca2+ with low micromolar affinity [22], [25], [26], which has been shown to interfere in an intracellular setting [28]. A notable exception is KMG-104 and related dyes developed by Kuzuki and coworkers, whose affinity for Mg2+ is higher than for Ca2+ (K d = 2.1 and 7.5 mM, respectively), rendering these dyes completely insensitive to physiological changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration [24], [29], [30]. Recently a variant of this dye, KMG-103 was reported that showed preferred accumulation in mitochondria [27]. Like most synthetic Mg2+ dyes, the KMG dyes are intensiometric, making Mg2+ quantification challenging and sensitive to changes in sensor concentration. A few ratiometric Mg2+ fluorescent dyes (e.g. Mag-Fura and Mag-Indo) exist, yet these have the disadvantage that they require potentially cytotoxic UV excitation [17].

Genetically encoded fluorescent sensor proteins provide an attractive alternative to small-molecule fluorescent sensors, because they do not require cell-invasive procedures, their concentration can be tightly controlled and they can be targeted to different locations in the cell [31]. Many of these sensors consist of metal binding domain(s) fused to a donor and an acceptor fluorescent domain capable of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET). Modulation of the distance and/or orientation of the fluorescent domains following metal binding affects the FRET efficiency, which can be detected as change in the emission ratio, an output signal that is independent of sensor concentration. In addition, the use of natural metal binding protein domains often ensures a physiologically relevant metal binding affinity and specificity. The wealth of genetically encoded sensors that have been developed for Ca2+ [32]–[35], and more recently also for Zn2+ [36]–[39] and Cu+ [40], [41], have made important contributions to the understanding of intracellular metal homeostasis and signaling.

Surprisingly, no genetically encoded sensors have thus far been reported for Mg2+. One of the specific challenges in this case is metal binding specificity. Mg2+ and Ca2+ show similar coordination chemistry and often bind to the same metal binding proteins, with Ca2+ typically showing stronger binding. Here we report the first genetically encoded fluorescent sensor (MagFRET-1) for Mg2+ by taking advantage of the particular metal binding properties of the N-terminal part of the HsCen3 protein, which binds both Ca2+ and Mg2+ with high affinity [42]. We show that Mg2+ binding to MagFRET-1 induces folding from a molten-globule state that results in an increase in FRET. Mutagenesis of metal binding site residues allowed further tuning of the metal binding properties, yielding MagFRET variants with K d values for Mg2+ binding ranging between 0.15 and 15 mM. While also responsive to Ca2+ in vitro, we show that the Ca2+ affinities of the MagFRET sensors are sufficiently attenuated that they are not responsive to normal Ca2+ fluctuations in situ.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of expression plasmids

DNA encoding the N-terminal fragment of HsCen3 (residues 23 to 98 [42]) was obtained as a synthetic pUC57 construct (GenScript, USA). Restriction of this construct with restriction enzymes NheI and NcoI yielded an insert fragment that was compatible with a pET28a acceptor vector encoding for His6-Cerulean-(GGS)18-Citrine [43] that had been treated with restriction enzymes SpeI (creating an NheI-compatible cohesive overhang) and NcoI. A ligation was carried out at equimolar vector-to-insert ratio using T4 DNA ligase (TaKaRA Mighty Mix, Takara, USA) at 16°C for 1 hour following the manufacturer's instructions, resulting in pET28a-MagFRET-1 (Figure S1). The SpeI restriction site in the pET28a-His6-Cerulean-(GGS)18-Citrine acceptor vector was located 8 residues upstream of the Cerulean C-terminus, such that in the final MagFRET construct, the native flexible C-terminus of Cerulean was deleted, resulting in tighter allosteric coupling between changes in HsCen3 conformation and changes in the fluorescent domains' interchromophore distance. The mammalian expression vector for MagFRET-1 was obtained by digesting pET28a-MagFRET-1 using restriction enzymes AgeI and NotI. Ligation into a peCALWY-1 vector [36] that was digested with the same restriction enzymes resulted in pCMV-MagFRET-1 ( Figure S2 ). Mutations in metal binding loop I and II of MagFRET-1 were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit for mutations in loop I and QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit for mutations in loop II), following the kit manufacturer's (Qiagen) instructions. Primers used to introduce these mutations are listed in Table S1. To obtain the mammalian expression vector encoding for a nuclear-targeted MagFRET-1 (MagFRET-1-NLS), a pUC57 vector containing a synthetic gene encoding for the final part of Citrine together with three PKKKRKV repeats was digested using restriction enzymes HindIII and NotI, followed by ligation into a pCMV-MagFRET-1 plasmid that was treated with the same restriction enzymes (Figure S3). The correct open reading frame of each sensor was confirmed by Sanger dideoxy sequencing (Baseclear, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Protein expression and purification

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were used for protein expression. A single colony was used to inoculate 5 mL LB medium (10 g/L NaCl, 10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L yeast extract) supplemented with 30 µg/mL kanamycin which was grown overnight at 225 rpm at 37°C. Overnight cultures were diluted in 500 mL LB medium containing kanamycin (30 µg/mL) and grown until an optical density of 0.6–0.8 was reached at 600 nm wavelength. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Sigma). Bacteria were cultured overnight at 225 rpm at 25°C and harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellets were lysed using Bugbuster reagent (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting soluble protein fraction was used for further purification. The expressed MagFRET proteins contain an N-terminal hexahistidine-tag. Ni2+-NTA resin (His-bind, Novagen) was used for affinity chromatography following the manufacturer's instructions. After elution of the protein using 0.5 M imidazole, the protein was dialyzed overnight against 100 volumes of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 150 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM CaCl2 using a 12–14 kDa Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) dialysis membrane (Spectropore) at 4°C. The hexahistidine-tag was subsequently removed by the addition of 0.3 U thrombin protease (Novagen) per mg protein at a 0.2 mg/mL protein concentration and incubated for 24 hours at 4°C. His-tags and uncleaved proteins were removed using Ni2+ affinity chromatography. The flow-through was further purified using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Sephacryl S-200 High resolution column (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing pure proteins were pooled, concentrated, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in aliquots at −80°C. The purity and correct molecular weight of the obtained proteins was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, with 12% acrylamide) analysis. The protein concentration was determined using the absorption at 515 nm (ND-1000 Nanodrop) and a molar extinction coefficient of 77,000 M−1cm−1 for Citrine [44].

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Unless otherwise mentioned, magnesium and calcium titrations were performed in 150 mM Hepes (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.1), 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded between 450 and 600 nm at a 0.2 µM protein concentration on a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorometer with an excitation wavelength of 420 nm. MgCl2 and CaCl2 (both from Sigma) were added at increasing concentrations from a concentrated stock solution in water. To determine the MagFRET-1 dissociation constant (Kd) for Mg2+, the emission ratio (R) as a function of MgCl2 concentration ([Mg2+]) was fit to equation 1,

| (1) |

where RS is the starting emission ratio in absence of Mg2+ and ΔR the difference in emission ratio between the Mg2+-free and Mg2+-saturated form of MagFRET-1. To determine the MagFRET Kd 1 and Kd 2 values associated with the first and second Ca2+-binding events respectively, the emission ratio (R) as a function of CaCl2 concentration ([Ca 2+]) was fit to a double binding event using equation 2,

| (2) |

where RS is the starting emission ratio in absence of Ca2+, ΔR 1 is the difference between the emission ratio in the Ca2+-free state and the state in which a single Ca2+ ion has bound to the first metal binding loop of HsCen3, ΔR 2 the difference between the latter state and the state in which a second Ca2+ ion has bound to EF-hand II. For the metal specificity measurements, either BaCl2, NiSO4, CuSO4, ZnCl2 or FeCl3 was added from 1000× concentration stock solutions to a final concentration of 10 µM, followed by addition of 1 mM MgCl2. For titrations (with MgCl2, NaCl and ammonium acetate) testing the effect of ionic strength on the sensor, a low salt buffer was used, consisting of 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), 10 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) glycerol. To test for pH sensitivity of MagFRET-1, MgCl2 and CaCl2 titrations were carried out in buffers where Hepes was replaced with either MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) or Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) in the standard measurement buffer. The MES-containing buffer was prepared at pH 6 while the Tris-containing buffer was prepared at pH 8.

Cell culturing and transfection

HEK293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Sigma) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies), 3 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units mL−1 penicillin and 100 µg mL−1 streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were plated on poly-L-lysine (Sigma) treated glass coverslips and transfected with 1.5 µg of plasmid DNA and 5 µg polyethyleneimine (PEI). Cells were imaged for transient expression 2 days after transfection. In addition to the pCMV-MagFRET-1 and pCMV-MagFRET-1-NLS constructs described above, cells were also transfected with peZinCh-NB [36], which encodes for the Cerulean-linker-Citrine protein that was used as a negative control. Details of the Western blot procedure are provided in Method S1.

Fluorescence microscopy

To demonstrate correct localization and subcellular targeting of MagFRET-1, confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5 X) was used to image the sensor with high spatial resolution. Samples were excited using a 405 nm laser and emission was detected using a hybrid APD/PMT detector (HyD, Leica). Spectral emission windows were set to 460–490 nm for the Cerulean channel and 510–550 nm for the Citrine channel, using an acousto optical beam splitter (AOBS, Leica). Widefield fluorescence microscopy for FRET measurements was performed on an Axio observer D.1 (Zeiss) equipped with an Axiocam MRm monochrome digital camera (Zeiss) using Axiovision 4.7 software. Samples were excited using a HXP 120 Mercury lamp (Zeiss) and Cerulean and Citrine emission was recorded sequentially using filter set 47 (excitation BP 436/20, dichroic 455, emission BP 480/40) and 48 (excitation BP 436/20, dichroic 455, emission BP 535/30) (Zeiss) in a motorized filter turret. Emission of Oregon Green-BAPTA was recorded using filterset 38 HE (excitation 470/40, dichroic 495, emission BP 525/50) (Zeiss). Images were acquired using an apochromat 40× objective, with an exposure time of 200–300 ms.

Imaging of response to changes in intracellular Mg2+

Prior to addition of Mg2+ or EDTA, cells were permeabilized by a 6 minute incubation of HEK293 cells in 400 µL intracellular buffer (IB) containing 10 µg/ml digitonin (Sigma). IB comprised 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.05), 140 mM KCl, 10 mM KH2PO4, 100 µM ATP, 2 mM Na+ succinate and 5.5 mM glucose. After 6 minutes, recordings were started and buffers containing increasing concentrations of EDTA or MgCl2 were added as stated in the main text. When adding MgCl2, KCl concentrations were reduced accordingly to maintain the Cl− concentration at 140 mM. Imaging frequency was 0.1 Hz.

Intracellular Ca2+ specificity

Intracellular calcium specificity measurements were performed on HEK293 cells transfected as described above. Modified Krebs-bicarbonate buffer was used, consisting of 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 140 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3 and 3 mM glucose. Where indicated, PAR-1 agonist peptide (sequence SFLLRN, Genscript, USA) or ATP (Sigma) were added to a final concentration of 50 µM. Control experiments were performed using non-transfected HEK293 cells that were loaded with 10 µM Oregon Green-BAPTA-AM (Life Technologies, Netherlands) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 0.01% (w/v) Pluronic F-127 (Life Technologies) for 30 minutes. At the end of each experiment in which Oregon Green-BAPTA-AM was used, 20 µM of calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma) was added. Imaging frequency was 0.2 Hz.

Results

Sensor design

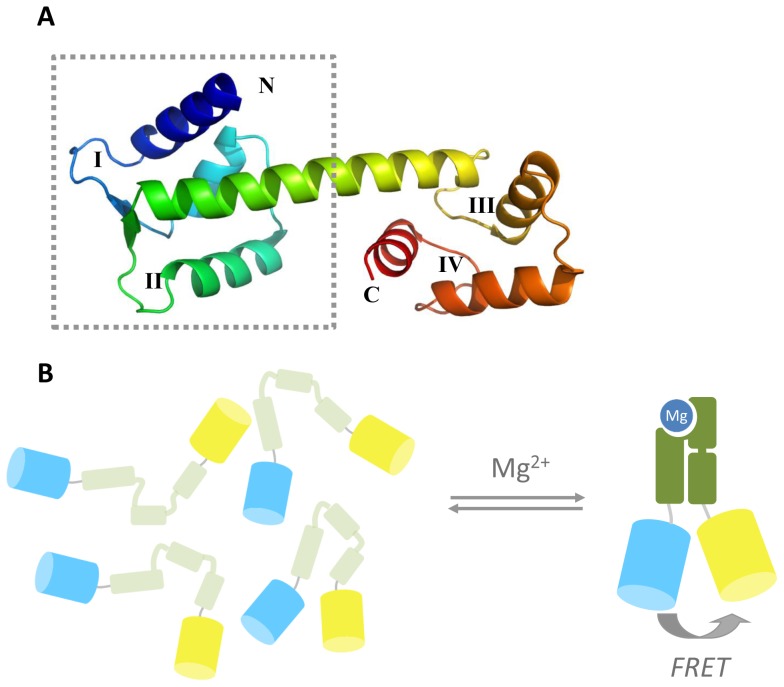

The construction of a FRET sensor for Mg2+ requires the availability of a metal binding domain that undergoes a large conformational change and displays a relatively high affinity for Mg2+ compared to Ca2+. Cox and coworkers previously reported that a truncated version of HsCen3 containing the first two of its four native EF-hand metal binding sites, undergoes a dramatic change in conformation upon metal binding from a molten globular (MG) state to a compact, natively-folded state [42]. Unlike most other EF hand-like proteins, which typically bind Ca2+ orders of magnitude more strongly than Mg2+, HsCen3's first EF hand is a high-affinity mixed Mg2+/Ca2+ binding site, with a reported K d for Mg2+ of 10–28 µM and a K d for Ca2+ of 1.5–8 µM. The second metal binding site was reported to bind only Ca2+, but with a much weaker affinity (K d = 140 µM). HsCen3 is one of the four isoforms of human Centrin, a family of proteins that is involved in centriole duplication. We based our design on the structure of HsCen2, which shows high homology to HsCen3 and is the only isoform for which an X-ray structure has been determined ( Figure 1A ). The 11 kDa N-terminal fragment studied by Cox and coworkers contained the complete α-helix connecting the 2nd and 3rd EF hand sites. To decrease the distance between the N- and C-termini of the receptor part in the Mg2+-bound state, we decided to truncate this helix to approximately half its size (aa 23–98) and fuse it to the fluorescent proteins Cerulean and Citrine ( Figure 1B ). To ensure that a conformational change of the HsCen3 domain in MagFRET-1 was translated to a maximal change in relative orientation of the fluorescent domains, the final 8 amino acids from the flexible C-terminus of Cerulean were removed.

Figure 1. Design of the genetically encoded magnesium FRET sensor MagFRET.

(A) Crystal structure (PDB code 2GGM) of HsCen2 in the calcium-bound, compact state. The typical helix-loop-helix structure can be observed, with EF-hands indicated by Roman numerals. The dotted lines indicate the N-terminal truncated part of the domain used in the sensor. In HsCen3, the high-affinity Mg2+/Ca2+ binding site is in loop I, and a much weaker Ca2+-binding site is found in loop II. (B) Schematic representation of MagFRET, where the N-terminal truncation of HsCen3 is flanked by Cerulean and Citrine. In absence of Mg2+, the HsCen3 domain is in a molten globule-like state, with little tertiary structure and a relatively large average distance between the fluorescent domains. Mg2+-binding induces a compact, well-defined tertiary structure, resulting in increased energy transfer between Cerulean and Citrine.

In vitro characterization of MagFRET-1

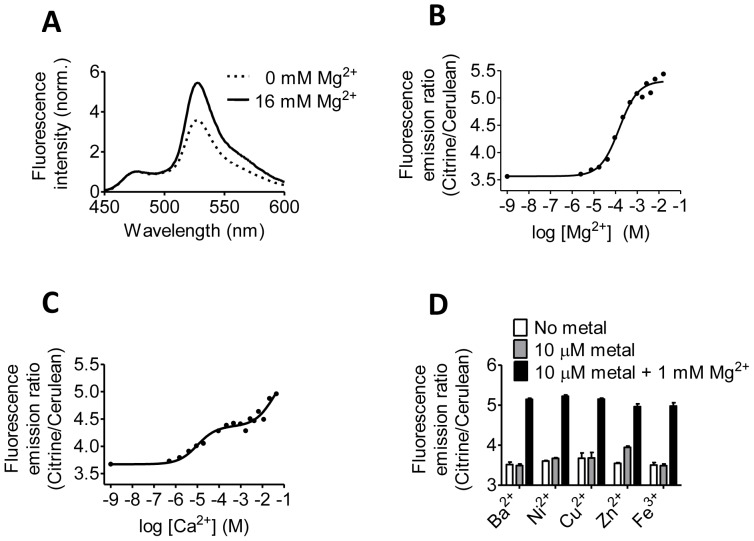

To allow characterization of MagFRET-1 in vitro, a His-tagged sensor construct was expressed in good yield in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified using Ni2+-affinity and size exclusion chromatography. A relatively high ratio of Citrine to Cerulean emission of 3.6 was observed in the absence of Mg2+, indicating that the molten globule state of the metal binding domain is relatively compact bringing the fluorescent domains close together ( Figure 2A ). As expected, a further increase in emission ratio of 50% was observed upon addition of Mg2+, which is consistent with the formation of a more compact metal-bound, native state. The increase in emission ratio could be fitted using a 1∶1 binding model, yielding a K d for Mg2+ of 148±23 µM ( Figure 2B ). Fortunately, this affinity is in the (lower) range of the cytosolic [Mg2+]free reported by previous methods, and 10-fold weaker than that reported by Cox et al. for their N-terminal variant of HsCen3 [42]. Since HsCen3 was reported to not only bind Mg2+ but also contain two Ca2+ binding sites [42], the Ca2+ response of MagFRET-1 was also tested. Addition of Ca2+ led to a biphasic increase in emission ratio, which was fitted to a 2∶1 binding model ( Figure 2C ). Binding of Ca2+ to the high affinity site showed a K d of 10±4 µM and resulted in a 19% increase in emission ratio. An additional 20% increase in emission ratio was observed at Ca2+ concentrations above 1 mM, but the low affinity for this site precluded accurate determination of its K d. While the absolute affinity of MagFRET-1 for Ca2+ is higher than for Mg2+, the sensor would not be expected to be sensitive to normal fluctuations in bulk cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, which range between 0.1 and 1 µM [45]. No increase in emission ratio was observed upon addition of 10 µM Ba2+, Ni2+, Cu2+ or Fe3+, while only a very small increase was seen for 10 µM Zn2+ ( Figure 2D ), a concentration that is 10,000-fold higher than the free Zn2+ concentration found in the cytosol [36]. Another important aspect of sensor performance is pH sensitivity. Ca2+ and Mg2+ titrations performed at pH 6 and pH 8 showed that metal binding affinities were unaffected within this pH range (Figure S4A–D). As expected, the absolute emission ratios where somewhat lower at pH 6, due to the pH sensitivity of Citrine, which has a pKa of 5.7 [44]. Finally, we noticed that the emission ratio of the apo form of the sensor is dependent on the ionic strength of the buffer (Figure S5A). When the Mg2+ titration was repeated in a low ionic strength buffer, the emission ratio of the apo form decreased to 2.2, whereas the emission ratio in the Mg2+-bound state was the same (Figure S5B) and the Mg2+ affinity remained mostly unaffected (K d = 231±10 µM). This ionic strength dependence most likely reflects the influence of ionic strength on the compactness of the molten globule structure of HsCen3. Although the effect is less pronounced at physiologically relevant salt concentrations, it does mean that large changes in ionic strength should be avoided when applying MagFRET-1 in situ.

Figure 2. Metal binding properties of MagFRET-1.

(A) Normalized fluorescence emission spectra of MagFRET-1 at 0 and at 16 mM Mg2+ after excitation at 420 nm. (B, C) Emission ratio (Citrine to Cerulean) of MagFRET-1 as a function of the Mg2+ (B) or Ca2+ (C) concentration. Solid lines indicate a fit to a single (B) or a double (C) binding event, yielding a K d of 0.15±0.02 mM for Mg2+ and K d's of 10±4 µM and ∼35 mM for Ca2+, respectively. (D) Emission ratios of MagFRET-1 in absence of metal, in the presence of 10 µM Ba2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+ or Fe3+, and in the presence of the same metals and 1 mM Mg2+. Measurements were performed in triplicate, error bars indicate SEM. All measurements were performed in 150 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), 100 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) glycerol with 0.2 µM sensor protein.

Tuning metal binding affinities

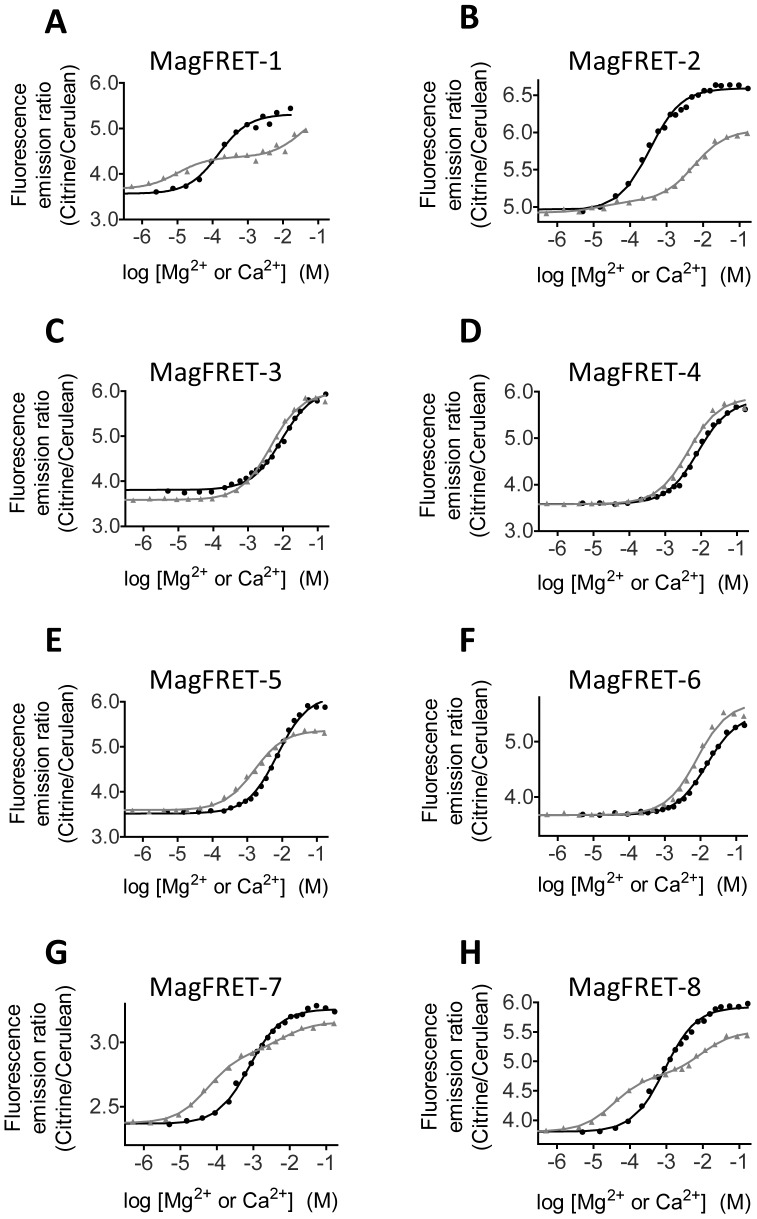

To test whether we could further tune the metal affinity and specificity of the MagFRET sensor we explored several mutations in both metal binding sites. Targeting key residues in the 1st EF hand (D1A, D3E, A7D and D5E/A7E) resulted in a reduction of both the Mg2+ and Ca2+ affinity to the millimolar regime, indicating that these residues are indeed directly involved in high affinity metal binding ( Table 1 , Figure 3C–F ). Only a single Ca2+ binding event was observed for these mutants, suggesting that the two EF hands in MagFRET-3-6 have a similar Ca2+ affinity, making the two binding events indistinguishable. Interestingly, an E6D substitution (MagFRET-2) did not alter the affinity for Mg2+ or Ca2+ ( Figure 3B , Table 1 ), showing that the presence of a glutamic acid at this position is not essential for high affinity metal binding. Although the change in emission ratio for binding Mg2+ is attenuated to 33% in this variant, the response to Ca2+ binding is almost absent for the high affinity site (3%), rendering this variant effectively Ca2+ insensitive. In an effort to abolish Ca2+ binding to the weakly Ca2+-binding EF hand II, we replaced aspartic acid 1 (MagFRET-7) and glycine 6 (MagFRET-8) at that site by positively charged lysine residues. Surprisingly, upon titration of Ca2+, both sensor variants still displayed the same biphasic response as seen with MagFRET-1 ( Figure 3A, G, H ), showing that neither of these residues is essential for the low affinity Ca2+ binding event in EF hand II. Interestingly, both the D1K and the G6K mutation subtly attenuated the high affinity mixed Ca2+/Mg2+ site in EF-hand I, leading to a 6- and 5-fold decrease of the Mg2+ affinity and a 6- and 4-fold decrease in Ca2+ affinity, respectively ( Figure 3G, H ). The somewhat weaker affinities for both Mg2+ and Ca2+ observed for MagFRET-7 and MagFRET-8 could prove beneficial for imaging Mg2+ homeostasis under conditions where the intracellular Mg2+ concentrations are higher.

Table 1. Sensor properties of the different MagFRET variants.

| Variant | 1st EF-h and sequence1 | 2nd EF-hand sequence1 | K d Mg2+/mM ± SE2 | D.R. Mg2+ binding event3 | K d,1 Ca2+/µM ± SE2 | D.R. 1st Ca2+ binding event3 |

| MagFRET-1 | DTDKDEAIDYHE | DREATGKITFED | 0.15±0.02 | 49% | 10±3.7 | 19% |

| MagFRET-2 | DTDKDDAIDYHE | DREATGKITFED | 0.35±0.03 | 33% | 15±9.8 | 3.1% |

| MagFRET-3 | ATDKDEAIDYHE | DREATGKITFED | 9.2±0.7 | 58% | 4500±243 | 66% |

| MagFRET-4 | DTEKDEAIDYHE | DREATGKITFED | 8.5±0.5 | 62% | 4500±311 | 64% |

| MagFRET-5 | DTDKDEDIDYHE | DREATGKITFED | 7.4±0.5 | 74% | 1600±116 | 49% |

| MagFRET-6 | DTDKEEEIDYHE | DREATGKITFED | 15±0.8 | 50% | 7900±786 | 55% |

| MagFRET-7 | DTDKDEAIDYHE | KREATGKITFED | 0.78±0.04 | 38% | 57±5 | 23% |

| MagFRET-8 | DTDKDEAIDYHE | DREATKKITFED | 0.89±0.06 | 56% | 36±5 | 25% |

Mutations introduced in the first or second 12-residue metal binding loops of HsCen3 are indicated in bold and are underlined.

The dissociation constant (K d) for each variant's Mg2+ and first Ca2+ binding event is indicated, together with the standard error (SE).

A binding event's dynamic range (D.R.) is defined as the difference in emission ratio between the unbound and fully metal bound form divided by the emission ratio in the unbound form, multiplied by 100%.

Figure 3. Mg2+/Ca2+ titrations of MagFRET variants with mutations in metal binding sites.

(A–H) Emission ratio (Citrine to Cerulean) of MagFRET variants as a function of the Mg2+ (black circles) or Ca2+ (grey triangles) concentration. Solid black traces indicate a fit to a Mg2+-binding event, while grey traces indicate a fit to either double Ca2+-binding events (A, B, G, H) or a single Ca2+-binding event (C–F). Results of the titrations are summarized in Table 1. Measurements were performed in 150 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), 100 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) glycerol and 0.2 (A) or 1 (B–H) µM protein.

In situ characterization of MagFRET-1 in HEK293 cells

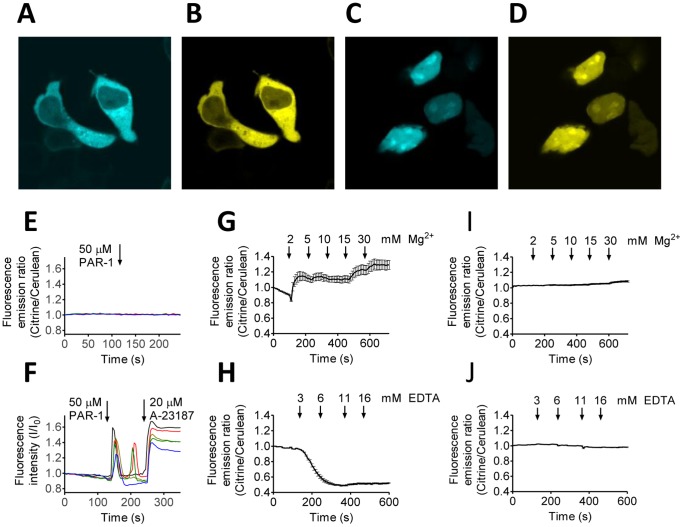

To assess the sensor properties of MagFRET-1 in situ, CMV vectors were constructed to allow transient expression of MagFRET-1 in HEK293 cells. Fluorescence microscopy images revealed homogeneous expression of the sensor in the cytosol ( Figure 4A, B ) and Western blot analysis showed a single band corresponding to the full-length protein (Figure S6). In addition, transfection of cells with a construct containing three repeats of the nuclear localization sequence PKKKRKV [46], [47] at the C-terminus of the sensor protein (MagFRET-1-NLS), resulted in a clear cyan and yellow emission in the nucleus ( Figure 4C, D ), which demonstrates the ability to target MagFRET-1 to a specific location in the cell. Although the K d of MagFRET-1 for Ca2+ determined in vitro is an order of magnitude higher than the maximum Ca2+ concentration that is typically observed in the cytosol during signaling, it was still important to verify that the MagFRET-1 sensor does not respond to stimuli that are known to transiently induce increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations. Ca2+ signaling in HEK293 cells was activated via addition of 50 µM of the protease activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) agonist peptide [48], [49]. No changes in the emission ratio of MagFRET-1 were observed after addition of this stimulant ( Figure 4E ). Cells loaded with the synthetic Ca2+ dye Oregon Green-BAPTA did show a transient increase in fluorescence upon addition of PAR-1 agonist peptide, confirming that the expected increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration was induced under these conditions ( Figure 4F ). Similar results were obtained with ATP, another commonly used stimulant for Ca2+ signaling [50]–[52]. Addition of 50 µM ATP did not affect the emission ratio of MagFRET-1 in HEK293 cells (Figure S7A), while cells loaded with Oregon Green-BAPTA showed a clear response to the same treatment (Figure S7B).

Figure 4. In situ characterization of MagFRET-1 in HEK293 cells.

(A–D) Confocal fluorescence microscopy images showing HEK293 cells expressing MagFRET-1 (A, B) and MagFRET-1-NLS (C, D) showing Cerulean (A,C) or Citrine emission (B, D). (E, F) Investigation of MagFRET-1's in situ Ca2+ sensitivity. (E) Emission ratio over time of intact HEK293 cells expressing MagFRET-1 measured by widefield fluorescence microscopy. At t = 120 s, 50 µM of PAR-1 agonist peptide was added to activate Ca2+ signaling. (F) To confirm Ca2+ signaling took place in stimulated cells, the fluorescence intensity of intact HEK293 cells loaded with Ca2+-dye Oregon Green–BAPTA was followed. At t = 120 s, 50 µM of PAR-1 agonist peptide was added to activate Ca2+ signaling, and at t = 240 s, 20 µM A23187 was added. In E and F, each trace represents the response of an individual cell, with ratio (E) or intensity (F) normalized to the value at t = 0 s. (G, H) Response of MagFRET-1 expressed in permeabilized HEK293 cells to changes in [Mg2+]. MagFRET-1 emission ratio was followed over time as the concentration of MgCl2 (G) or EDTA (H) was increased, as indicated on the panels. (I, J) Response of negative control construct Cerulean-linker-Citrine expressed in permeabilized HEK293 cells to changes in [Mg2+]. To maintain an isotonic solution, the increase in Cl− concentration due to addition of MgCl2 was compensated for by reducing the KCl concentration in the buffer. Prior to imaging, cells were permeabilized using 10 µg/mL digitonin. Traces in G to J represent averages of at least 9 cells, error bars indicate SEM, ratios were normalized to the emission ratio at t = 0.

Having established that MagFRET-1 could be targeted and that it was insensitive to normal cytosolic Ca2+ fluctuations, we next characterized MagFRET-1's ability to report on changes in cytosolic [Mg2+]free. Surprisingly, attempts to perturb the free concentration of Mg2+ in the cytosol of intact HEK293 cells using previously reported procedures did not induce a significant ratiometric response in HEK293 cells transfected with MagFRET-1 (not shown). These protocols included incubation of the cells in 50 mM MgCl2 [29], exposure to the Mg2+ competitor Li+ [53] and varying of the sodium concentration to affect the Mg2+/Na+ exchanger [54]. To verify that the transiently expressed sensor is still responsive, we permeabilized HEK293 cells transfected with MagFRET-1 using 10 µg/mL digitonin and exposed them to buffers with different Mg2+ or EDTA concentrations ( Figure 4G–J ). Addition of 2 mM Mg2+ resulted in an increase in emission ratio for MagFRET-1, indicating metal binding to this sensor ( Figure 4G ). Subsequent addition of increasing Mg2+ concentrations did not result in a further increase in emission ratio up to 10 mM, while rounding of cells was observed at concentrations of 15 and 30 mM Mg2+ (not shown). To verify that the sensor could also monitor a decrease in cytosolic Mg2+ levels, the metal chelator EDTA was added to permeabilized cells expressing MagFRET-1. Upon addition of EDTA, cells expressing MagFRET-1 showed a decrease in emission ratio that is consistent with a decrease in cytosolic Mg2+ levels ( Figure 4H ). Importantly, no changes in emission ratio were observed upon addition of Mg2+ or EDTA to digitonin-treated cells expressing a negative control construct consisting of Cerulean, a flexible linker and Citrine but lacking any metal binding sites ( Figure 4I, J ). These results exclude the possibility that changes in emission ratio observed in MagFRET-1-expressing cells may have resulted from changes in the fluorescent domains' properties due to their sensitivity to pH or [Cl−] and confirm that MagFRET-1 is capable of responding to changes in intracellular Mg2+ levels.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first report of a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor for Mg2+. The new sensor principle of metal-induced folding of an EF-hand protein was used to create a FRET-based sensor protein that combines a physiologically relevant Mg2+ affinity with a 50% increase in emission ratio upon Mg2+ binding. Mutations introduced in the metal binding domains yielded sensor variants with different degrees of attenuation in Mg2+ affinity, generating a toolbox of MagFRET variants for different applications. Unlike most synthetic fluorescent Mg2+ probes reported so far, MagFRET-1 allows emission ratiometric detection of Mg2+ and is thus less sensitive to fluctuations in sensor concentration or background fluorescence. A general advantage of genetically encoded sensors is that their subcellular localization can be easily controlled, as we demonstrated by targeting MagFRET-1 to the cytosol and nucleus of HEK293 cells. Importantly, while MagFRET-1 is also sensitive to Ca2+, its Ca2+ affinity is sufficiently attenuated to make the sensor effectively unresponsive to the Ca2+ levels reached during signaling. Although MagFRET-1 was clearly responsive to changes in Mg2+ in permeabilized HEK293 cells, we did not observe similar changes in emission ratio for intact cells. A lack of selective Mg2+ ionophores and chelators is a fundamental problem in the Mg2+ imaging field [4] and prevented us from calibrating the sensor's resting emission ratio by depleting and saturating the sensor in situ, as is commonly done for genetically encoded Ca2+ and Zn2+ sensors.

Despite the intrinsically large conformational change associated with protein folding, surprisingly few examples of FRET sensors exist where ligand-induced folding of a partially unfolded receptor domain is employed in FRET sensor design. Most FRET sensors developed so far either use ligand binding domains that are known to undergo significant conformational changes upon ligand binding (e.g. the periplasmic binding proteins [55]), or receptor domains that undergo a ligand-induced interaction with another peptide/protein domain (e.g. Cameleons [32]). Ligand-induced folding is believed to occur for intrinsically-disordered proteins, which may account for 35–51% of all eukaryotic protein domains [56]. In addition, ligand binding domains can be intentionally destabilized to turn conformationally silent ligand binding domains into attractive input domains for FRET sensor design [57]. This work revealed that ligand-induced folding of intrinsically-disordered proteins is an attractive mechanism for FRET sensor design. However, it also identified a potential disadvantage as we observed that the conformation and thus the amount of energy transfer of the ligand-free state is sensitive to ionic strength. Although this effect is most apparent below physiologically relevant salt concentrations, it is important to be aware of this phenomenon and use these sensors under conditions of constant ionic strength or use appropriate control sensors that have a strongly attenuated Mg2+ affinity, such as e.g. MagFRET-6.

The Mg2+ and Ca2+ affinity of MagFRET-1 were found to be attenuated compared to the affinities previously reported for the N-terminal domain of HsCen3 (K d = 10–28 µM for Mg2+; K d = 1.5–8 and 140 µM for Ca2+). The difference in metal binding affinity might be explained by the fact that the central α-helix that connects the 2nd and 3rd EF hands in HsCen3 was reduced to half its length in MagFRET-1, possibly further destabilizing the N-terminal domain, resulting in a net decrease in Mg2+ affinity. Fortunately, in this case the attenuation yielded a sensor that is sensitive to physiologically relevant Mg2+ concentrations, and insensitive to normal cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations. The limited number of metal binding domain mutations that were explored in this study revealed that mutations in the first EF hand typically result in strongly attenuated metal binding affinities. A more subtle, 4–6 fold attenuation of metal binding affinity was obtained after introduction of positively charged amino acids in the 2nd EF hand. These effects could be due to direct allosteric coupling between the two EF hands in the metal-bound state, but alternatively could also result from further stabilization of the molten globule state. An important goal is to develop sensor variants that are less sensitive to Ca2+ yet retain affinity for Mg2+, as this would allow targeting to organelles known to have much higher resting levels of Ca2+. The similar coordination chemistries of Ca2+ and Mg2+ make rational design of such variants challenging, although mutations in an EF-hand-like protein have been reported that decreased the Ca2+ affinity 100-fold while simultaneously doubling the Mg2+ affinity [58]. Further optimization of metal binding affinity and specificity, but also the sensor's dynamic range, may benefit from directed evolution approaches similar to the ones that were recently applied to develop new color variants of the Ca2+ sensor GECO [34], [59].

In situ characterization of MagFRET-1 in HEK293 cells revealed that the sensor is readily expressed in the cytosol and can be targeted to the nucleus. Two ligands that are known to induce Ca2+ signaling in cells, PAR-1 agonist peptide and ATP, did not affect the emission ratio of the MagFRET-1 sensor in HEK 293 cells. This result was expected based on the affinity of MagFRET-1 that was determined in vitro (K d = 10 µM) and previous reports that show that bulk cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations typically reach a maximum of 1 µM during signaling [45]. In contrast, synthetic Mg2+ dyes with similar affinity to Ca2+ as MagFRET-1 have been reported to respond to Ca2+. This may be explained by the fact that MagFRET-1 is exclusively localized in the cytosol, whereas synthetic dyes sometimes partially mislocalize to Ca2+-rich organelles such as the ER or even leak into the external buffer [60]. Surprisingly, HEK293 cells expressing MagFRET-1 did not respond to procedures that were previously reported to affect the intracellular Mg2+ concentration. A possible explanation is that the free concentration of Mg2+ in the cytosol is tightly buffered and controlled and not easily changed by external stimuli. The free concentration of Mg2+ in the cytosol is at least 1000-fold higher than that of Ca2+ and 106-fold higher than that of Zn2+. For this reason and because Mg2+ is essential to such a wide variety of biological processes, it would not be surprising that manipulation of intracellular free Mg2+ is much more difficult than that of other metals. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that while the overall free Mg2+ concentration in cells is relatively constant, substantial and physiologically relevant fluctuations in Mg2+ concentration could still occur locally, e.g. at the plasma membrane near Mg2+-specific ion channels. Although MagFRET-1 responded to changes in Mg2+ concentration in the order of seconds both in vitro and in cells, protein-based sensors often display slower kinetics than small molecule sensors, so that MagFRET-1 might fail to respond to extremely fast Mg2+ transients, should they occur. In addition, overall Mg2+ levels could change over longer periods of time, e.g. as a function of the cell cycle. These changes may be more reliably monitored using lifetime imaging, which might also be the preferred method to allow quantification of intracellular Mg2+ concentrations. Although we confirmed that MagFRET-1 is responsive to changes in Mg2+ concentration in permeabilized cells, we cannot completely rule out that for some unknown reason MagFRET-1 is less responsive in intact cells. The potential and limitations of the MagFRET sensors for intracellular Mg2+ imaging therefore remain to be further established.

Supporting Information

Nucleotide sequence of bacterial expression vector pET28a-MagFRET-1 ORF. The DNA sequence is shown in lowercase, with the single letter amino acid code shown beneath each codon in uppercase. The His-tag is highlighted in bright green, the thrombin cleavage site in pink, Cerulean in turquoise, HsCen3 in red and Citrine in yellow. The two EF-hand motifs are underlined in white.

(PDF)

Nucleotide sequence of mammalian expression vector pCMV-MagFRET-1 ORF. The DNA sequence is shown in lowercase, with the single letter amino acid code shown beneath each codon in uppercase. Cerulean is highlighted in turquoise, HsCen3 in red and Citrine in yellow. The two EF-hand motifs are underlined in white.

(PDF)

Nucleotide sequence of mammalian expression vector pCMV-MagFRET-1-NLS ORF. The DNA sequence is shown in lowercase, with the single letter amino acid code shown beneath each codon in uppercase. Cerulean is highlighted in turquoise, HsCen3 in red, Citrine in yellow and the three PKKKRKV repeats in grey. The two EF-hand motifs are underlined in white.

(PDF)

Effect of pH on MagFRET-1. To check for pH sensitivity, the MagFRET-1 emission ratio was followed as a function of Mg2+ (A, B) and Ca2+ (C, D) concentration, at pH 6 (A, C) and pH 8 (B, D). Fitting of the data revealed a MagFRET-1 K d for Mg2+ of 230±35 µM at pH 6 and 99±18 µM at pH 8. The sensor's K d for Ca2+ (first binding event) at pH = 6 was found to be 5.6±1.7 µM, while at pH 8 it was 5.9±1.9 µM. Buffers used were 150 mM MES (pH 6), 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol for pH 6 and 150 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol for pH 8.

(TIF)

Effect of ionic strength on MagFRET-1. (A) Emission ratio of MagFRET-1 at increasing concentrations of ammonium acetate or NaCl in a buffer with low ionic strength. (B) Emission ratio of MagFRET-1 as a function of Mg2+ concentration in a buffer with low ionic strength. The low ionic strength buffer used in (A, B) was 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), 10 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol. Fitting of the data using a single binding event revealed a K d for Mg2+ of 231±10 µM.

(TIF)

Western blot analysis of MagFRET-1 expressing HEK293 cells. A molecular weight marker (Precision Plus Protein Standards, Bio-Rad) was loaded in the left-hand lane. Lane 1 displays the lysate of HEK293 cells transfected with a vector encoding for MagFRET-1 under control of a CMV promoter. The blotting membrane was incubated with mouse anti-GFP (Ab3277, Abcam), followed by HRP-functionalized goat anti-mouse antibody (Dako). The calculated molecular weight for MagFRET-1 is 62 kDa.

(TIF)

Investigation of MagFRET-1 response to elevated cytosolic Ca2+ induced by ATP. (A) Emission ratio over time of intact HEK293 cells expressing MagFRET-1 measured by widefield fluorescence microscopy. At t = 104 s, 50 µM ATP was added to activate Ca2+ signaling. (B) To confirm Ca2+ signaling took place in stimulated cells, the fluorescence intensity of intact HEK293 cells loaded with Ca2+-dye Oregon Green–BAPTA was followed. At t = 104 s, 50 µM ATP was added to activate Ca2+ signaling, and at t = 226 s, 20 µM of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 was added. In A and B, each trace represents the response of an individual cell, with ratio (A) or intensity (B) normalized to the value at t = 0 s.

(TIF)

Western blotting.

(PDF)

Primers used for mutagenesis of HsCen3.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the use of the fluorescence confocal microscope in the Laboratory of Soft Tissue Biomechanics & Engineering (Eindhoven University of Technology) and appreciate the technical assistance provided by Dr. Ir. M. van Turnhout. The authors would like to thank Dr. Kees Jalink (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam), Dr. Stan van de Graaf (Academic Medical Centre), Dr. Sjoerd Verkaart, Dr. Jenny van der Wijst, Prof. Joost Hoenderop and Prof. René Bindels (Radboud University Nijmegen) for fruitful discussions.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research NWO (VIDI grant 700.56.428) and by an ERC starting grant(280255). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Shi J, Krishnamoorthy G, Yang Y, Hu L, Chaturvedi N, et al. (2002) Mechanism of magnesium activation of calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 418: 876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nadler MJ, Hermosura MC, Inabe K, Perraud AL, Zhu Q, et al. (2001) LTRPC7 is a Mg.ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature 411: 590–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Romani AM (2007) Magnesium homeostasis in mammalian cells. Front Biosci 12: 308–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grubbs RD (2002) Intracellular magnesium and magnesium buffering. Biometals 15: 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rutter GA, Osbaldeston NJ, McCormack JG, Denton RM (1990) Measurement of matrix free Mg2+ concentration in rat heart mitochondria by using entrapped fluorescent probes. Biochem J 271: 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gunther T (2006) Concentration, compartmentation and metabolic function of intracellular free Mg2+ . Magnes Res 19: 225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corkey BE, Duszynski J, Rich TL, Matschinsky B, Williamson JR (1986) Regulation of free and bound magnesium in rat hepatocytes and isolated mitochondria. J Biol Chem 261: 2567–2574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maguire ME (2006) The structure of CorA: a Mg2+-selective channel. Curr Opin Struct Biol 16: 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schlingmann KP, Waldegger S, Konrad M, Chubanov V, Gudermann T (2007) TRPM6 and TRPM7-Gatekeepers of human magnesium metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta, Molecular Basis of Disease 1772: 813–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hattori M, Tanaka Y, Fukai S, Ishitani R, Nureki O (2007) Crystal structure of the MgtE Mg2+ transporter. Nature 448: 1072–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Konrad M, Weber S (2003) Recent advances in molecular genetics of hereditary magnesium-losing disorders. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Killilea DW, Ames BN (2008) Magnesium deficiency accelerates cellular senescence in cultured human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 5768–5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaudhary DP, Sharma R, Bansal DD (2010) Implications of magnesium deficiency in type 2 diabetes: a review. Biol Trace Elem Res 134: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bo S, Pisu E (2008) Role of dietary magnesium in cardiovascular disease prevention, insulin sensitivity and diabetes. Curr Opin Lipidol 19: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rude RK, Gruber HE (2004) Magnesium deficiency and osteoporosis: animal and human observations. J Nutr Biochem 15: 710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li FY, Chaigne-Delalande B, Kanellopoulou C, Davis JC, Matthews HF, et al. (2011) Second messenger role for Mg2+ revealed by human T-cell immunodeficiency. Nature 475: 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trapani V, Farruggia G, Marraccini C, Iotti S, Cittadini A, et al. (2010) Intracellular magnesium detection: imaging a brighter future. Analyst 135: 1855–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen SM, Burt CT (1977) 31P nuclear magnetic relaxation studies of phosphocreatine in intact muscle: determination of intracellular free magnesium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74: 4271–4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Resnick LM, Gupta RK, Laragh JH (1984) Intracellular free magnesium in erythrocytes of essential hypertension: relation to blood pressure and serum divalent cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81: 6511–6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gunther T (2007) Total and free Mg2+ contents in erythrocytes: a simple but still undisclosed cell model. Magnes Res 20: 161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim HM, Yang PR, Seo MS, Yi J-S, Hong JH, et al. (2007) Magnesium ion selective two-photon fluorescent probe based on a benzo[h]chromene derivative for in vivo imaging. J Org Chem 72: 2088–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hwan Myung K, Cheol J, Bo Ra K, Soon-Young J, Jin Hee H, et al. (2007) Environment-sensitive two-photon probe for intracellular free magnesium ions in live tissue. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 46: 3460–3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Komatsu H, Miki T, Citterio D, Kubota T, Shindo Y, et al. (2005) Single molecular multianalyte (Ca2+, Mg2+) fluorescent probe and applications to bioimaging. J Am Chem Soc 127: 10798–10799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Komatsu H, Iwasawa N, Citterio D, Suzuki Y, Kubota T, et al. (2004) Design and synthesis of highly sensitive and selective fluorescein-derived magnesium fluorescent probes and application to intracellular 3D Mg2+ imaging. J Am Chem Soc 126: 16353–16360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raju B, Murphy E, Levy LA, Hall RD, London RE (1989) A fluorescent indicator for measuring cytosolic free magnesium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 256: C540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paredes RM, Etzler JC, Watts LT, Zheng W, Lechleiter JD (2008) Chemical calcium indicators. Methods 46: 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shindo Y, Fujii T, Komatsu H, Citterio D, Hotta K, et al. (2011) Newly developed Mg2+-selective fluorescent probe enables visualization of Mg2+ dynamics in mitochondria. PLoS One 6: e23684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hurley TW, Ryan MP, Brinck RW (1992) Changes of cytosolic Ca2+ interfere with measurements of cytosolic Mg2+ using mag-fura-2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 263: C300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou H, Clapham DE (2009) Mammalian MagT1 and TUSC3 are required for cellular magnesium uptake and vertebrate embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 15750–15755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xie J, Sun B, Du J, Yang W, Chen HC, et al. (2011) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP(2)) controls magnesium gatekeeper TRPM6 activity. Sci Rep 1: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Palmer AE, Qin Y, Park JG, McCombs JE (2011) Design and application of genetically encoded biosensors. Trends Biotechnol 29: 144–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, Michael McCaffery J, Adams JA, et al. (1997) Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388: 882–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palmer AE, Giacomello M, Kortemme T, Hires SA, Lev-Ram V, et al. (2006) Ca2+ indicators based on computationally redesigned calmodulin-peptide pairs. Chem Biol 13: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao YX, Araki S, Jiahui WH, Teramoto T, Chang YF, et al. (2011) An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science 333: 1888–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, et al. (2009) Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods 6: 875–U113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vinkenborg JL, Nicolson TJ, Bellomo EA, Koay MS, Rutter GA, et al. (2009) Genetically encoded FRET sensors to monitor intracellular Zn2+ homeostasis. Nat Methods 6: 737–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dittmer PJ, Miranda JG, Gorski JA, Palmer AE (2009) Genetically encoded sensors to elucidate spatial distribution of cellular zinc. J Biol Chem 284: 16289–16297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miranda JG, Weaver AL, Qin Y, Park JG, Stoddard CI, et al. (2012) New alternately colored FRET sensors for simultaneous monitoring of Zn2+ in multiple cellular locations. PLoS One 7: e49371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qiao W, Mooney M, Bird AJ, Winge DR, Eide DJ (2006) Zinc binding to a regulatory zinc-sensing domain monitored in vivo by using FRET. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 8674–8679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wegner SV, Arslan H, Sunbul M, Yin J, He C (2010) Dynamic copper(I) imaging in mammalian cells with a genetically encoded fluorescent copper(I) sensor. J Am Chem Soc 132: 2567–2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koay MS, Janssen BM, Merkx M (2013) Tuning the metal binding site specificity of a fluorescent sensor protein: from copper to zinc and back. Dalton Trans 42: 3230–3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cox JA, Tirone F, Durussel I, Firanescu C, Blouquit Y, et al. (2005) Calcium and magnesium binding to human centrin 3 and interaction with target peptides. Biochemistry 44: 840–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Golynskiy MV, Rurup WF, Merkx M (2010) Antibody detection by using a FRET-based protein conformational switch. ChemBioChem 11: 2264–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Griesbeck O, Baird GS, Campbell RE, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY (2001) Reducing the environmental sensitivity of yellow fluorescent protein. J Biol Chem 276: 29188–29194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bootman MD (2012) Calcium signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a011171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE (1984) A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell 39: 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fischer-Fantuzzi L, Vesco C (1988) Cell-dependent efficiency of reiterated nuclear signals in a mutant simian virus 40 oncoprotein targeted to the nucleus. Mol Cell Biol 8: 5495–5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiang T, Danilo P Jr, Steinberg SF (1998) The thrombin receptor elevates intracellular calcium in adult rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 30: 2193–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hui KY, Jakubowski JA, Wyss VL, Angleton EL (1992) Minimal sequence requirement of thrombin receptor agonist peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 184: 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Isshiki M, Ando J, Korenaga R, Kogo H, Fujimoto T, et al. (1998) Endothelial Ca2+ waves preferentially originate at specific loci in caveolin-rich cell edges. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 5009–5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A (2004) Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 10554–10559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Qi Z, Murase K, Obata S, Sokabe M (2000) Extracellular ATP-dependent activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ pump in HEK-293 cells. Br J Pharmacol 131: 370–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fonseca CP, Montezinho LP, Baltazar G, Layden B, Freitas DM, et al. (2000) Li+ influx and binding, and Li+/Mg2+ competition in bovine chromaffin cell suspensions as studied by 7Li NMR and fluorescence spectroscopy. Met Based Drugs 7: 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schweigel M, Park HS, Etschmann B, Martens H (2006) Characterization of the Na+-dependent Mg2+ transport in sheep ruminal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Okumoto S, Looger LL, Micheva KD, Reimer RJ, Smith SJ, et al. (2005) Detection of glutamate release from neurons by genetically encoded surface-displayed FRET nanosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 8740–8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z (2002) Intrinsic disorder and protein function. Biochemistry 41: 6573–6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kohn JE, Plaxco KW (2005) Engineering a signal transduction mechanism for protein-based biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 10841–10845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang W, Barnabei MS, Asp ML, Heinis FI, Arden E, et al. (2013) Noncanonical EF-hand motif strategically delays Ca2+ buffering to enhance cardiac performance. Nat Med 19: 305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lindenburg L, Merkx M (2012) Colorful calcium sensors. ChemBioChem 13: 349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Trapani V, Schweigel-Rontgen M, Cittadini A, Wolf FI (2012) Intracellular magnesium detection by fluorescent indicators. Methods Enzymol 505: 421–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nucleotide sequence of bacterial expression vector pET28a-MagFRET-1 ORF. The DNA sequence is shown in lowercase, with the single letter amino acid code shown beneath each codon in uppercase. The His-tag is highlighted in bright green, the thrombin cleavage site in pink, Cerulean in turquoise, HsCen3 in red and Citrine in yellow. The two EF-hand motifs are underlined in white.

(PDF)

Nucleotide sequence of mammalian expression vector pCMV-MagFRET-1 ORF. The DNA sequence is shown in lowercase, with the single letter amino acid code shown beneath each codon in uppercase. Cerulean is highlighted in turquoise, HsCen3 in red and Citrine in yellow. The two EF-hand motifs are underlined in white.

(PDF)

Nucleotide sequence of mammalian expression vector pCMV-MagFRET-1-NLS ORF. The DNA sequence is shown in lowercase, with the single letter amino acid code shown beneath each codon in uppercase. Cerulean is highlighted in turquoise, HsCen3 in red, Citrine in yellow and the three PKKKRKV repeats in grey. The two EF-hand motifs are underlined in white.

(PDF)

Effect of pH on MagFRET-1. To check for pH sensitivity, the MagFRET-1 emission ratio was followed as a function of Mg2+ (A, B) and Ca2+ (C, D) concentration, at pH 6 (A, C) and pH 8 (B, D). Fitting of the data revealed a MagFRET-1 K d for Mg2+ of 230±35 µM at pH 6 and 99±18 µM at pH 8. The sensor's K d for Ca2+ (first binding event) at pH = 6 was found to be 5.6±1.7 µM, while at pH 8 it was 5.9±1.9 µM. Buffers used were 150 mM MES (pH 6), 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol for pH 6 and 150 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol for pH 8.

(TIF)

Effect of ionic strength on MagFRET-1. (A) Emission ratio of MagFRET-1 at increasing concentrations of ammonium acetate or NaCl in a buffer with low ionic strength. (B) Emission ratio of MagFRET-1 as a function of Mg2+ concentration in a buffer with low ionic strength. The low ionic strength buffer used in (A, B) was 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), 10 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol. Fitting of the data using a single binding event revealed a K d for Mg2+ of 231±10 µM.

(TIF)

Western blot analysis of MagFRET-1 expressing HEK293 cells. A molecular weight marker (Precision Plus Protein Standards, Bio-Rad) was loaded in the left-hand lane. Lane 1 displays the lysate of HEK293 cells transfected with a vector encoding for MagFRET-1 under control of a CMV promoter. The blotting membrane was incubated with mouse anti-GFP (Ab3277, Abcam), followed by HRP-functionalized goat anti-mouse antibody (Dako). The calculated molecular weight for MagFRET-1 is 62 kDa.

(TIF)

Investigation of MagFRET-1 response to elevated cytosolic Ca2+ induced by ATP. (A) Emission ratio over time of intact HEK293 cells expressing MagFRET-1 measured by widefield fluorescence microscopy. At t = 104 s, 50 µM ATP was added to activate Ca2+ signaling. (B) To confirm Ca2+ signaling took place in stimulated cells, the fluorescence intensity of intact HEK293 cells loaded with Ca2+-dye Oregon Green–BAPTA was followed. At t = 104 s, 50 µM ATP was added to activate Ca2+ signaling, and at t = 226 s, 20 µM of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 was added. In A and B, each trace represents the response of an individual cell, with ratio (A) or intensity (B) normalized to the value at t = 0 s.

(TIF)

Western blotting.

(PDF)

Primers used for mutagenesis of HsCen3.

(PDF)